Public Officials’ Knowledge of Advances and Gaps for Implementing the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chilean Fisheries Management

2.2. Research Strategies

2.2.1. Knowledge on Advances and Gaps

2.2.2. Prioritization of EAF Dimensions

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge on Advances and Gaps for the Application of the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries (EAP) in Chile

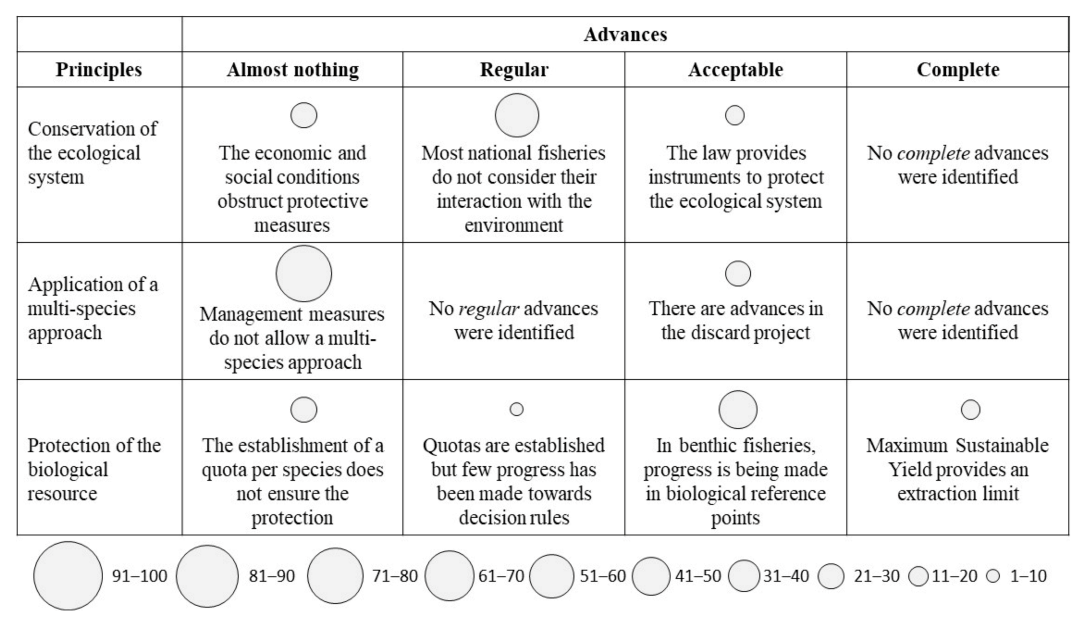

3.1.1. Ecological and Biological Dimensions

Conservation of the Ecological System

Application of a Multi-Species Approach

Protection of the Biological Resource

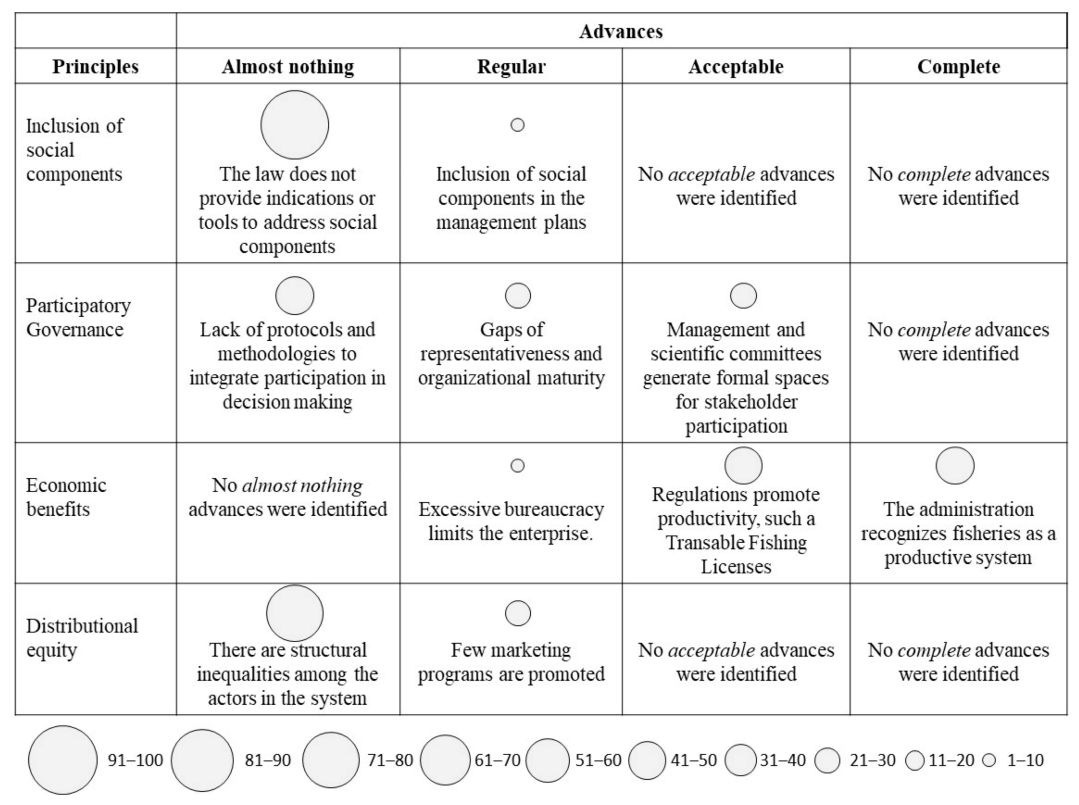

3.1.2. Social and Economic Dimensions

Inclusion of Social Components

Participatory Governance

Economic Benefits

Distributional Equity

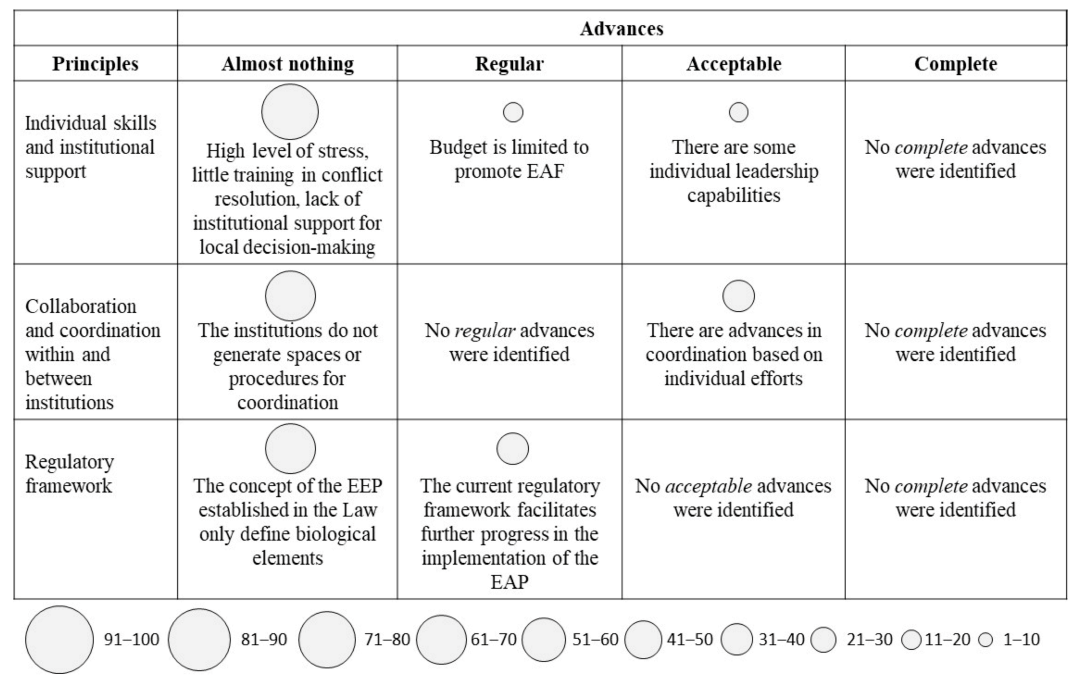

3.1.3. Institutional Dimensions

Individual Skills and Institutional Support

Collaboration and Coordination within and between Institutions

Regulatory Framework

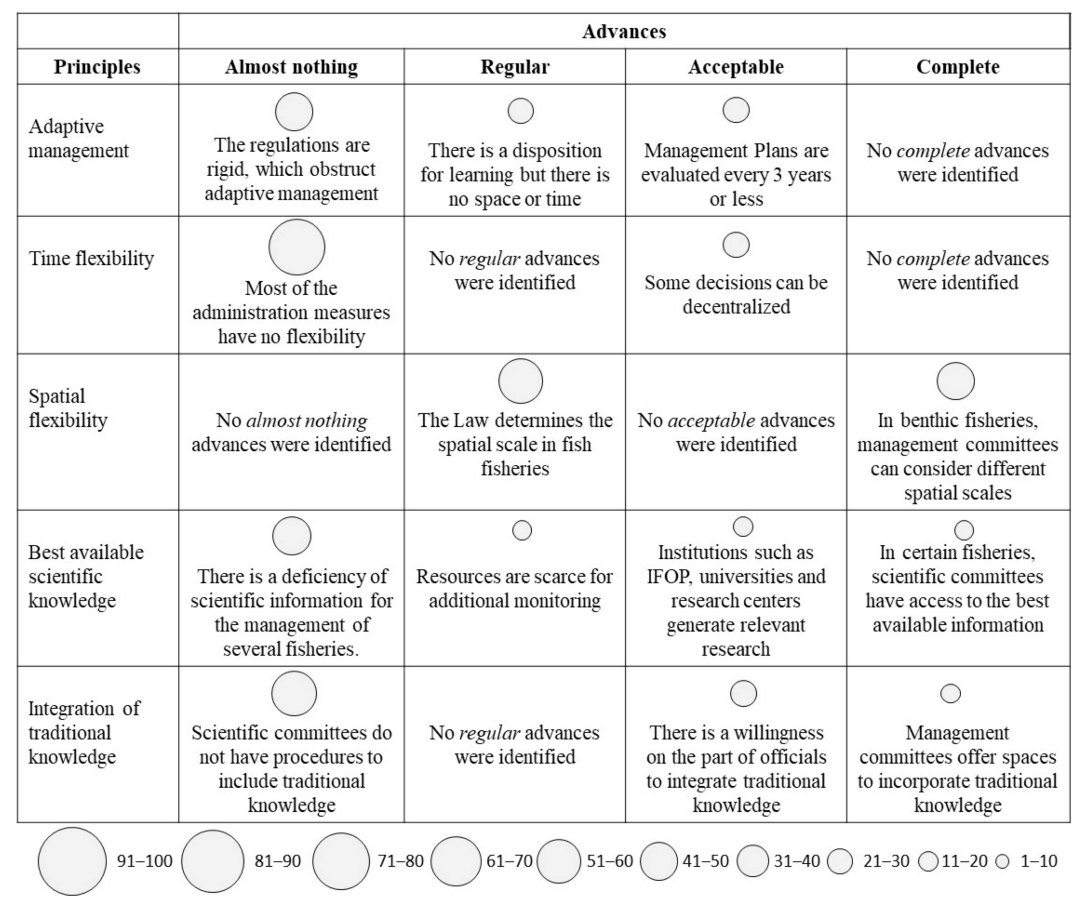

3.1.4. Knowledge Systems and Scale Dimensions

Adaptive Management

Time Flexibility

Spatial Flexibility

Best Available Scientific Information

Integration of Traditional Knowledge

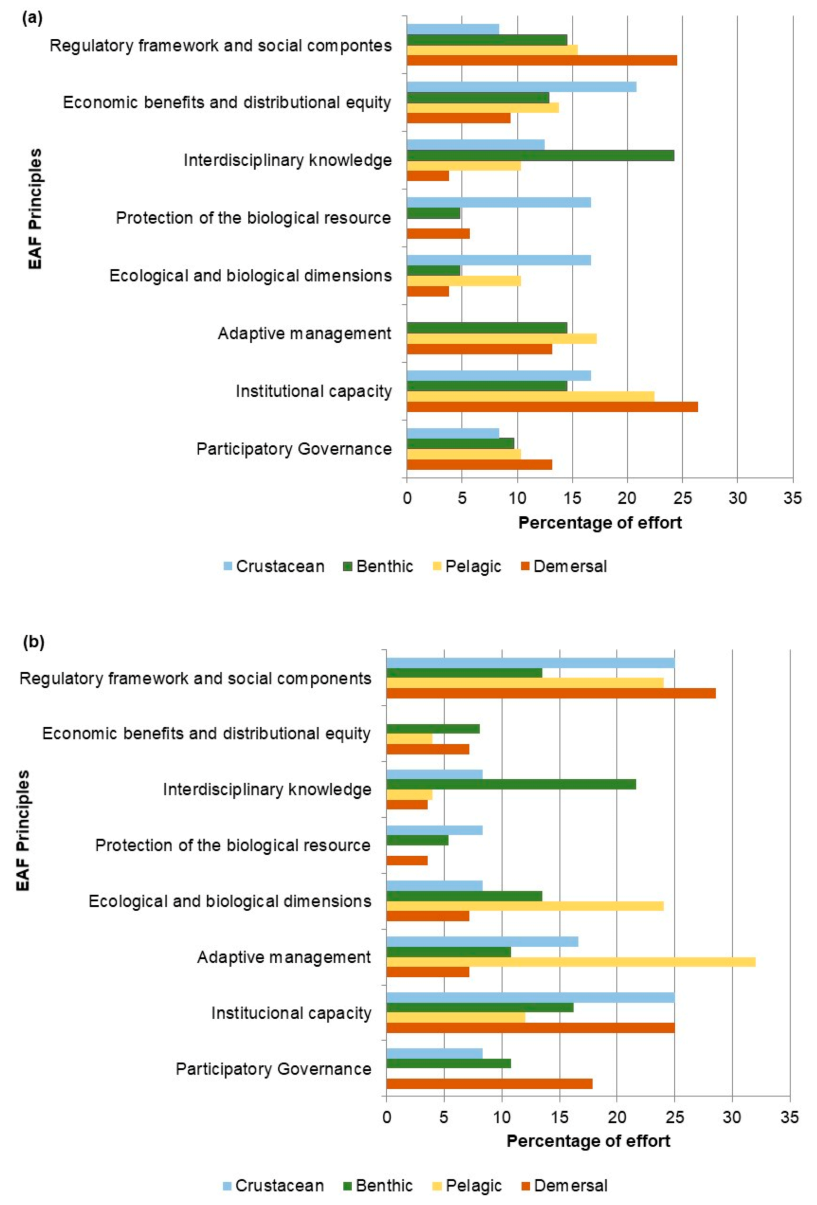

3.2. Prioritization of Dimensions for Strengthening the Ecosystem Approach

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimensions | Desired State |

|---|---|

| Conservation of the ecological system | Fisheries management regulates the extractive processes of the resource to protect the functioning and structure of the ecological system of which the resource is a part. |

| Application of a multi-species approach | Fisheries recognize the interconnectedness and potential impact of management actions on other ecosystems and resources, management measures consider multiple species simultaneously. |

| Protection of the biological resource | The fisheries establish a Target Reference Point or the maximum sustainable yield through a scientific method, the compliance with this estimated value ensures the long-term maintenance of these resources avoiding overexploitation. |

| Inclusion of social components | Fisheries management considers the human, cultural, and social dimensions, ensuring the long-term sustainability of each of these elements. |

| Participatory Governance | Fisheries management recognizes that management is a multi-group decision, and allows for participation in decision-making. |

| Economic benefits | Fisheries management is recognized as a productive system, promoting the generation of economic benefits. |

| Distributional equity | Fisheries management allows the economic benefits generated to be distributed equitably among the participating stakeholders. |

| Individual skills and institutional support | The government offices in charge of implementing the ecosystem approach to fisheries management have the individual skills and institutional support to lead the process. |

| Collaboration and coordination within and between institutions | Institutions with responsibilities in fisheries management coordinate and collaborate for their efficient management. |

| Regulatory framework | Fisheries management is regulated by an appropriate legal framework for the implementation of the EAF, considering the multidimensionality of sustainable development. |

| Adaptive management | Fisheries administration generates conditions for adaptive management, especially understood as the capacity for institutional and collective learning in those decision-making instances. |

| Time flexibility | Fisheries management is flexible to establish management decisions considering the time scale. |

| Spatial flexibility | Fisheries administration is flexible to establish management decisions considering spatial scale. |

| Best available scientific information | Fisheries management uses the best available scientific information, which is generated in a timely manner by universities and research centers. |

| Integration of traditional knowledge | Fisheries management considers the traditional or local knowledge available for decision-making. |

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in Action; Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, R.K.F.; McKenzie, L.J.; Collier, C.J.; Cullen-Unsworth, L.C.; Duarte, C.M.; Eklof, J.S.; Jarvis, J.C.; Jones, B.L.; Nordlund, L.M. Global challenges for seagrass conservation. Ambio 2019, 48, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.L.; Yuan, J.J.; Lu, X.T.; Su, C.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Wang, C.C.; Cao, X.H.; Li, Q.F.; Su, J.L.; Ittekkot, V.; et al. Major threats of pollution and climate change to global coastal ecosystems and enhanced management for sustainability. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 239, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloczanska, E.S.; Brown, C.J.; Sydeman, W.J.; Kiessling, W.; Schoeman, D.S.; Moore, P.J.; Brander, K.; Bruno, J.F.; Buckley, L.B.; Burrows, M.T.; et al. Global imprint of climate change on marine life. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, S.; Kupek, E. Poverty and childhood undernutrition in developing countries: A multi-national cohort study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngonghala, C.N.; Plucinski, M.M.; Murray, M.B.; Farmer, P.E.; Barrett, C.B.; Keenan, D.C.; Bonds, M.H. Poverty, Disease, and the Ecology of Complex Systems. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development Initiatives Poverty Research. Global Nutrition Report: Action on Equity to End Malnutrition; Development Initiatives: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, C.; Cao, L.; Gelcich, S.; Cisneros-Mata, M.Á.; Free, C.M.; Froehlich, H.E.; Golden, C.D.; Ishimura, G.; Maier, J.; Macadam-Somer, I.; et al. The future of food from the sea. Nature 2020, 588, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S., III; Pickett, S.T.A.; Power, M.; Jackson, R.; Carter, D.; Duke, C. Earth stewardship: A strategy for social-ecological transformation to reverse planetary degradation. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2011, 1, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.B.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Swilling, M.; Allison, E.H.; Österblom, H.; Gelcich, S.; Mbatha, P. A transition to sustainable ocean governance. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, G. The concept of the ecosystem approach to fisheries in FAO. In The Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries; Bianchi, G., Skjoldal, H.R., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries: Issues, Terminology, Principles, Institutional Foundations, Implementation and Outlook; Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- CBD. CBD Guidelines: The Ecosystem Approach; Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD): Montreal, QC, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mangel, M.; Talbot, L.; Meffe, G.; Agardy, T.; Alverson, D.; Barlow, J.; Botkin, D.; Budowski, G.; Clark, T.; Cooke, J.; et al. Principles for the Conservation of Wild Living Resources. Ecol. Appl. 2001, 6, 338–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.D.; Charles, A.; Stephenson, R.L. Key principles of marine ecosystem-based management. Mar. Policy 2015, 57, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, M.; Rose, K. The art of ecosystem-based fishery management. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 71, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, W.; Link, J. Myths that Continue to Impede Progress in Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management. Fisheries 2015, 40, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawski, S.A. Ten myths concerning ecosystem approaches to marine resource management. Mar. Policy 2007, 31, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianelli, I.; Horta, S.; Martinez, G.; de la Rosa, A.; Defeo, O. Operationalizing an ecosystem approach to small-scale fisheries in developing countries: The case of Uruguay. Mar. Policy 2018, 95, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelcich, S.; Reyes-Mendy, F.; Arriagada, R.; Castillo, B. Assessing the implementation of marine ecosystem based management into national policies: Insights from agenda setting and policy responses. Mar. Policy 2018, 92, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, B.; Petersen, S. EAF implementation in Southern Africa: Lessons learnt. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.; Shackley, S. Reconceiving Science and Policy: Academic, Fiducial and Bureaucratic Knowledge. Minerva 1999, 37, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlan, C.J.; Wilcox, C.; Luque, G.M.; Gelcich, S. Estimating illegal fishing from enforcement officers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischman, F.; Briske, D. Professional ecological knowledge: An unrecognized knowledge domain within natural resource management. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Edelenbos, J.; van Buuren, A.; van Schie, N. Co-producing knowledge: Joint knowledge production between experts, bureaucrats and stakeholders in Dutch water management projects. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Asistencia para la Revisión de la Ley General de Pesca y Acuicultura, en el Marco de los Instrumentos, Acuerdos y Buenas Prácticas Internacionales para la Sustentabilidad y Buena Gobernanza del Sector Pesquero; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO): Santiago, Chile, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Castilla, J. Fisheries in Chile: Small pelagics, management, rights, and sea zoning. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2010, 86, 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- SERNAPESCA. Anuario Estadístico de Pesca y Acuicultura; Servicio Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura (SERNAPESCA): Valparaíso, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gelcich, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Defeo, O.; Fernandez, M.; Foale, S.; Gunderson, L.H.; Rodriguez-Sickert, C.; Scheffer, M.; et al. Navigating transformations in governance of Chilean marine coastal resources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16794–16799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelcich, S.; Martínez-Harms, M.J.; Tapia-Lewin, S.; Vasquez-Lavin, F.; Ruano-Chamorro, C. Comanagement of small-scale fisheries and ecosystem services. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, e12637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, R.; Gelcich, S. Collective action spaces and transformations in the governance of fisheries resources towards democratic and deliberative management. In Marine and Fisheries Policies in Latin America: A Comparison of Selected Countries; Muller, M., Oyanedel, R., Monteferri, B., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gelcich, S.; Reyes-Mendy, F.; Rios, M.A. Early assessments of marine governance transformations: Insights and recommendations for implementing new fisheries management regimes. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, R.A.; Veloso, C.; Jerez, G.; Gelcich, S. A participatory decision making framework for artisanal fisheries collaborative governance: Insights from management committees in Chile. Nat. Resour. Forum 2020, 44, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; SAGE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hilborn, R. The evolution of quantitative marine fisheries management 1985–2010. Nat. Resour. Model. 2012, 25, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaichas, S.; Gamble, R.; Fogarty, M.; Benoît, H.; Essington, T.; Fu, C.; Koen-Alonso, M.; Link, J. Assembly rules for aggregate-species production models simulations in support of management strategy evaluation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 459, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S.; Chuenpagdee, R. Fisheries and coastal governance as a wicked problem. Mar. Policy 2009, 33, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PNUD. Diez años de Auditoría a la Democracia: Antes del Estallido; Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD): Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, B.; Isaacs, M.; Hara, M.; Jarre, A.; Moloney, C.L. Transdisciplinary co-operation for an ecosystem approach to fisheries: A case study from the South African sardine fishery. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S. Beyond fisheries management: The Phronetic dimension. Mar. Policy 2006, 30, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryhn, A.C.; Lundstrom, K.; Johansson, A.; Stabo, H.R.; Svedang, H. A continuous involvement of stakeholders promotes the ecosystem approach to fisheries in the 8-fjords area on the Swedish west coast. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pikitch, E.; Santora, C.; Babcock, E.; Bakun, A.; Bonfil, R.; Conover, D.; Dayton, P.; Doukakis, P.; Fluharty, D.; Houde, E.; et al. Ecosystem-Based Fishery Management. Science 2004, 305, 346–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Smith, A.D.M.; Punt, A.E.; Richardson, A.J.; Gibbs, M.; Fulton, E.A.; Pascoe, S.; Bulman, C.; Bayliss, P.; Sainsbury, K. Ecosystem-based fisheries management requires a change to the selective fishing philosophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9485–9489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.; Cochrane, K. Ecosystem approach to fisheries: A review of implementation guidelines. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2005, 62, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, E.A.; Smith, A.D.M.; Smith, D.C.; Johnson, P. An integrated approach is needed for ecosystem based fisheries management: Insights from ecosystem-level management strategy evaluation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R.; Phang, K.H.W.; Ramdass, K.; Saad, J.M.; Lokani, P.; Mayo-Anda, G.; Lorenzo, E.; Manero, G.; Maguad, Z.; Pido, M.D.; et al. Moving towards an ecosystem approach to fisheries management in the Coral Triangle region. Mar. Policy 2015, 51, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, H.; Adhuri, D.S.; Adrianto, L.; Andrew, N.L.; Apriliani, T.; Daw, T.; Evans, L.; Garces, L.; Kamanyi, E.; Mwaipopo, R.; et al. An ecosystem approach to small-scale fisheries through participatory diagnosis in four tropical countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 36, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, E.A.; Smith, A.D.M.; Smith, D.C.; van Putten, I.E. Human behaviour: The key source of uncertainty in fisheries management. Fish Fish. 2011, 12, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J. Managing fisheries well: Delivering the promises of an ecosystem approach. Fish Fish. 2011, 12, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Human Dimensions of the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries: An Overview of Context, Concepts, Tools and Methods; Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arkema, K.K.; Abramson, S.C.; Dewsbury, B.M. Marine ecosystem-based management: From characterization to implementation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 4, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, L.J.; Jarre, A.C.; Petersen, S.L. Developing a science base for implementation of the ecosystem approach to fisheries in South Africa. Prog. Oceanogr. 2010, 87, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortnam, M.P. Forces opposing sustainability transformations: Institutionalization of ecosystem-based approaches to fisheries management. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, S.; Rice, J. Towards an ecosystem approach to fisheries in Europe: A perspective on existing progress and future directions. Fish Fish. 2011, 12, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Policy and Operational Framework for Integrated Management of Estuarine, Coastal and Marine Environments in Canada; Fisheries and Oceans Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, W.; Chesson, J.; Sainsbury, K.; Hundloe, T.; Fisher, M. National ESD Reporting Framework for Australian Fisheries: The ESD Assessment Manual for Wild Capture Fisheries; FRDC Project 2002/086; Ecologically Sustainable Development, and Fisheries Research & Development Corporation: Canberra, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Estevez, R.; Gelcich, S. Participative multi-criteria decision analysis in marine management and conservation: Research progress and the challenge of integrating value judgments and uncertainty. Mar. Policy 2015, 61, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Definition |

|---|---|

| Conservation of the ecological system | EAF seeks to ensure the health of the entire ecological system, especially safeguarding the capacity of the ecosystem to maintain its structure and functioning |

| Application of a multi-species approach | the EAF pursues a multi-species approach rather than a monospecific approach to resource management, considering the interconnection among the various species present in the ecosystem |

| Protection of the biological resource | EAF ensure the maintenance of living resources by preventing them from being threatened by over-exploitation, based on target reference limits |

| Inclusion of social components | The EAF proposes a sustainable view of fisheries, incorporating humans and their cultural diversity as explicit objectives in the management |

| Participatory Governance | EAF requires a decentralized management of resources, engaging stakeholders in decision-making processes |

| Economic benefits | The EAF recognizes the potential economic benefits derived from the extraction of marine resources, improving marketing processes, and generating added value in the products |

| Distributional equity | The EAF promotes conditions to reduce market distortions, and the equitably distribution of benefits from fisheries |

| Individual skills and institutional support | EAF requires individual competencies and institutional support for its effective implementation, including instances of accompaniment, and capacities for conflict resolution |

| Collaboration and coordination within and between institutions | EAF implementation is based on effective coordination and collaboration among institutions and social organizations |

| Regulatory framework | The EAF requires adequate regulatory frameworks to enable a multidimensional and sustainable development |

| Adaptive management | The EAF has a dynamic and adaptive character, based on a collective learning process in decision-making spaces for fisheries administration |

| Time and spatial flexibility | the EAF recognizes that marine resource management must be adapted to multiple spatial and temporal variations |

| Best available scientific knowledge | the EAP is characterized by the use of the best available scientific information for decision-making, considering the knowledge generated by multiple disciplines |

| Integration of traditional knowledge | The EAF promotes a holistic perspective to understand environmental problems, integrating the traditional knowledge of local communities as valid information |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Estévez, R.A.; Gelcich, S. Public Officials’ Knowledge of Advances and Gaps for Implementing the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries in Chile. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052703

Estévez RA, Gelcich S. Public Officials’ Knowledge of Advances and Gaps for Implementing the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries in Chile. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052703

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstévez, Rodrigo A., and Stefan Gelcich. 2021. "Public Officials’ Knowledge of Advances and Gaps for Implementing the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries in Chile" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052703

APA StyleEstévez, R. A., & Gelcich, S. (2021). Public Officials’ Knowledge of Advances and Gaps for Implementing the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries in Chile. Sustainability, 13(5), 2703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052703