Construction of Leisure Consumer Loyalty from Cultural Identity—A Case of Cantonese Opera

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Evaluate the cultural identity of Cantonese opera consumers.

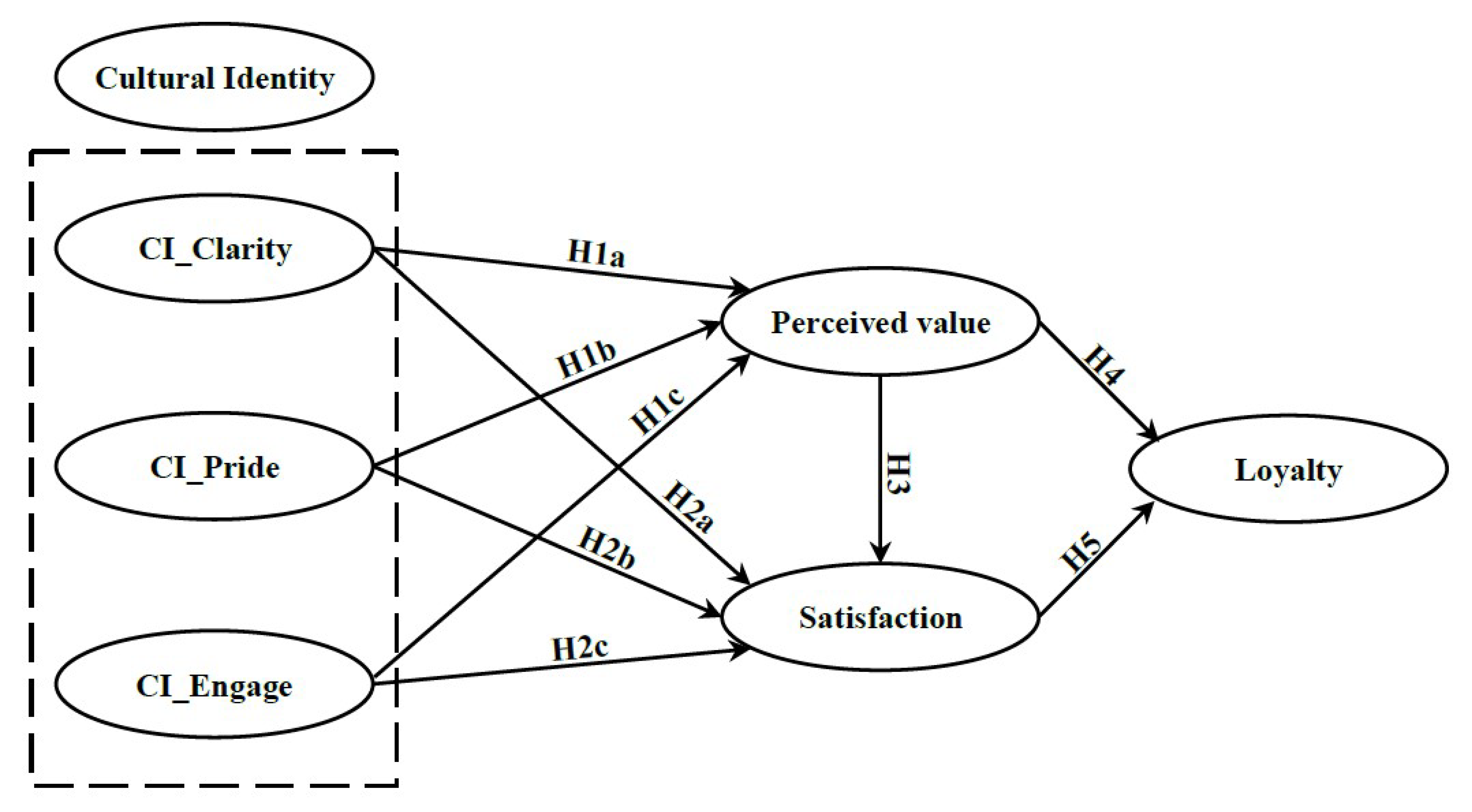

- Create a theoretical research model to study the effects of cultural identity on loyalty in the context of Cantonese opera as cultural leisure.

- Provide recommendations and suggestions to the Cantonese opera organisation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Leisure and Cantonese Opera

2.2. Cultural Identity

2.3. Perceived Value

2.4. Satisfaction

2.5. Loyalty

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Instrument

3.2. Data Collection and Respondent Profile

4. Result

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

4.2. Structure Model Evaluation

5. Conclusions

6. Implications and Future Research

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI_Clarity | Clarity dimension of Cultural Identity |

| CI_Pride | Pride dimension of Cultural Identity |

| CI_Engage | Engagement dimension of Cultural Identity. |

| Val | Perceived Value |

| Sat | Satisfaction |

| Loy | Loyalty |

References

- Wade, P. Cultural Identity: Solution or Problem? Institute for Cultural Research: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, F.; Ranahan, P.; Linds, W.; Goulet, L. Leisure, cultural continuity, and life promotion. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Graefe, A.R. Roller-skating into the big city: A case study of migrant workers’ informal leisure activity in Guangzhou, China. J. Leis. Res. 2019, 50, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fu, J. Religious leisure, heritage and identity construction—A case of Tibetan college students. Leis. Stud. 2019, 38, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, S.-H.; Malonebeach, E.; Heo, J. Migrating to the East: A qualitative investigation of acculturation and leisure activities. Leis. Stud. 2014, 35, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Leisure Activities and Leisure Skills of Urban Residents in Hangzhou, China. In Balancing Development and Sustainability in Tourism Destinations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann, K.; Artime, C.M.; Breuer, C.; Dallmeyer, S.; Metz, M. Leisure participation: Modelling the decision to engage in sports and culture. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 41, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, Y. Artists, Tourists, and the State: Cultural Tourism and the Flamenco Industry in Andalusia, Spain. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 80–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, N.S.; Burkhalter, J.N.; Yo, D.J. That’s My Brand: An Examination of Consumer Response to Brand Placements in Hip-Hop Music. J. Advert. 2014, 44, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, C.L. Cultural identity and consumer ethnocentrism impacts on preference and purchase of domestic versus import brands: An empirical study in China. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthi, L.; Raj, S.P. An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between Brand Loyalty and Consumer Price Elasticity. Mark. Sci. 1991, 10, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havitz, M.E.; Mannell, R.C. Enduring Involvement, Situational Involvement, and Flow in Leisure and Non-leisure Activities. J. Leis. Res. 2005, 37, 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Graefe, A.; Manning, R.; Bacon, J. Predictors of Behavioral Loyalty among Hikers Along the Appalachian Trail. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Petrick, J.F. Towards an Integrative Model of Loyalty Formation: The Role of Quality and Value. Leis. Sci. 2010, 32, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J. Destination Branding as an Informational Signal and Its Influence on Satisfaction and Loyalty in the Leisure Tourism Market; Virginia Tech: Virginia, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, G.-M. Structural Equation Modeling between Leisure Involvement, Consumer Satisfaction, and Behavioral Loyalty in Fitness Centers in Taiwan; United States Sports Academy: Daphne, AL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel, P. Puerto Rican Music and Cultural Identity: Creative Appropriation of Cuban Sources from Danza to Salsa. Ethnomusicology 1994, 38, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Dong, E. Place construction and public space: Cantonese opera as leisure in the urban parks of Guangzhou, China. Leis. Stud. 2017, 37, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, J.E. What is Leisure? An Empirical Analysis of the Concept of Leisure and the Role of Leisure in People’s Lives; Sports Council and Economic and Social Research Council: Swindon, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe, J. The Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S.J.; Hall, C.M. The Geography of Tourism and Recreation: Environment, Place and Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.D.; Stebbins, R.A. Amateurs, Professionals, and Serious Leisure. Can. J. Sociol. Cah. Can. Sociol. 1993, 18, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, R.A. Casual leisure: A conceptual statement. Leis. Stud. 1997, 16, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, J.D. What is Identity (as We Now Use the Word); Unpublished manuscript; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organisations: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Cappella, J.N. The Role of Theory in Developing Effective Health Communications. J. Commun. 2006, 56, S1–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.M.; Barker, G.G. Confused or multicultural: Third culture individuals’ cultural identity. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2012, 36, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, N.M. The Dynamic Nature of Cultural Identity Throughout Cultural Transitions: Why Home Is Not So Sweet. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 4, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.-K.; Cheung, L.H. Cultural identity and language: A proposed framework for cultural globalisation and glocalisation. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2011, 32, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.Y. Intercultural Personhood: Globalisation and a Way of Being. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2008, 32, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meca, A.; Sabet, R.F.; Farrelly, C.M.; Benitez, C.G.; Schwartz, S.J.; Gonzales-Backen, M.; Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Unger, J.B.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; et al. Personal and cultural identity development in recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents: Links with psychosocial functioning. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2017, 23, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.; Gibson, C. World music: Deterritorialising place and identity. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 28, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandellero, A.; Janssen, M.; Cohen, S.; Roberts, L. Popular music heritage, cultural memory and cultural identity. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 20, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoeven, A.; Brandellero, A. Places of popular music heritage: The local framing of a global cultural form in Dutch museums and archives. Poetics 2015, 51, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Io, M.-U.; Chong, D. Determining residents’ enjoyment of Cantonese opera as their performing arts heritage in Macao. Ann. Leis. Res. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S.; DuPont, S.; Espinosa, C.; Revill, J.; Sanders, K. Ethnic identity and American identification among ethnic minority youths. In Journeys into Cross-Cultural Psychology Subtitle: Selected Papers from the Eleventh International Conference of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology; Tilburg University: Tilburg, The Netherlands, 1994; p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- Juang, L.P.; Nguyen, H.H. Ethnic Identity among Chinese-American Youth: The Role of Family Obligation and Community Factors on Ethnic Engagement, Clarity, and Pride. Identity 2010, 10, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.M.; Yoo, H.C. Structure and Measurement of Ethnic Identity for Asian American College Students. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Lemon, K.N. A dynamic model of customers’ usage of services: Usage as an antecedent and consequence of satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Peterson, R.T. Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: The role of switching costs. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Tsai, M.-H. Perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty of TV travel product shopping: Involvement as a moderator. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, N.; Lee, H.; Lee, S. Event Quality, Perceived Value, Destination Image, and Behavioral Intention of Sports Events: The Case of the IAAF World Championship, Daegu, 2011. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandža Bajs, I. Tourist perceived value, relationship to satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: The example of the Croatian tourist destination Dubrovnik. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.; Yeh, T.-M.; Pai, F.-Y.; Huang, T.-P. Sport Activity for Health!! The Effects of Karate Participants’ Involvement, Perceived Value, and Leisure Benefits on Recommendation Intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, W.A.; McDonald, M.A.; Milne, G.R.; Cimperman, J. Creating and fostering fan identification in professional sports. Sport Mark. Q. 1997, 6, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Borden, R.J.; Thorne, A.; Walker, M.R.; Freeman, S.; Sloan, L.R. Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1976, 34, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.H.; Trail, G.; James, J.D. The Mediating Role of Perceived Value: Team Identification and Purchase Intention of Team-Licensed Apparel. J. Sport Manag. 2007, 21, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, D. Cultural Brands/Branding Cultures. J. Mark. Manag. 2005, 21, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Scholer, A.A. Engaging the consumer: The science and art of the value creation process. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.D.; Beatty, S.E.; Morgan, R.M. Customer Engagement: Exploring Customer Relationships beyond Purchase. J. Mark. Theory Pr. 2012, 20, 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. Repeaters’ behavior at two distinct destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 784–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M.C.; Paggiaro, A. Investigating the role of festivalscape in culinary tourism: The case of food and wine events. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Gibson, H.; Sisson, L. The loyalty process of residents and tourists in the festival context. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, M.; Goh, B.K. An examination of food tourist’s behavior: Using the modified theory of reasoned action. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Crotts, J. Relationships between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and tourist satisfaction: A cross-country cross-sample examination. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chick, G.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Yeh, C.-K.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Ramer, S.; Bae, S.Y.; Xue, L.; Dong, E. Cultural Consonance Mediates the Effects of Leisure Constraints on Leisure Satisfaction: A Reconceptualisation and Replication. Leis. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, K.; Koenig-Lewis, N.; Palmer, A.; Probert, J. Festivals as agents for behaviour change: A study of food festival engagement and subsequent food choices. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; Van Der Veen, R.; Huang, S.; Deesilatham, S. Mediating Effects of Place Attachment and Satisfaction on the Relationship between Tourists’ Emotions and Intention to Recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organising framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronge, S.; Sengupta, N.K.; Barlow, F.K.; Osborne, D.; Houkamau, C.; Sibley, C.G. Perceived discrimination predicts increased support for political rights and life satisfaction mediated by ethnic identity: A longitudinal analysis. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2016, 22, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmer, J.M.; Chen, W. Corporate heritage brands, augmented role identity and customer satisfaction. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 1510–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B. Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.; El-Gohary, H. The role of Islamic religiosity on the relationship between perceived value and tourist satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, M.; Sullivan Mort, G. The consequence of appraisal emotion, service quality, perceived value and customer satisfaction on repurchase intent in the performing arts. J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, R.; Clemes, M.; Dean, D. The Mediating Role of Perceived Value on the Relationship between Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction: Evidence from Indonesian Airline Passengers. Procedia Econ. Finance 2016, 35, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.R.; Shani, A.; Walls, A. The Value of Destination Loyalty: Myth or Reality? J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S.M. A Consumer-Brand Relationship Framework for Strategic Brand Management. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Parasuraman, A.; Grewal, D.; Voss, G.B. The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. An Examination of the Relationship between Golf Travelers’ Satisfaction, Perceived Value and Loyalty and Their Intentions to Revisit; Clemson University: Clemson, SC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hapsari, R.; Clemes, M.D.; Dean, D. The impact of service quality, customer engagement and selected marketing constructs on airline passenger loyalty. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2017, 9, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jen, W.; Tu, R.; Lu, T. Managing passenger behavioral intention: An integrated framework for service quality, satisfaction, perceived value, and switching barriers. Transportation 2011, 38, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoondnejad, A. Tourist loyalty to a local cultural event: The case of Turkmen handicrafts festival. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.T.; Illum, S.F. Examining the mediating role of festival visitors’ satisfaction in the relationship between service quality and behavioral intentions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2006, 12, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Petrick, J.F.; Crompton, J. The Roles of Quality and Intermediary Constructs in Determining Festival Attendees’ Behavioral Intention. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, C.-K. Measuring festival quality and value affecting visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty using a structural approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. J. Adolesc. Res. 1992, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Soutar, G.N. Value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in an adventure tourism context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Wong, J.W.C.; Cheng, C.-C. An Empirical Study of Behavioral Intentions in the Food Festival: The Case of Macau. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 19, 1278–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Duncan, J.; Chung, B.W. Involvement, Satisfaction, Perceived Value, and Revisit Intention: A Case Study of a Food Festival. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2014, 13, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B.; Wang, Y. The Role of Customer Engagement in Building Consumer Loyalty to Tourism Brands. J. Travel Res. 2014, 55, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Visitors’ Emotional Responses to the Festival Environment. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pr. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychological Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. Stat. Strateg. Small Sample Res. 1999, 1, 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to Write Up and Report PLS Analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, A. Global ethnoscapes: Notes and queries for a transnational anthropology. In Recapturing Anthropology; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1996; pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, N.; Lee, S.; Lee, H. The Effect of Experience Quality on Perceived Value, Satisfaction, Image and Behavioral Intention of Water Park Patrons: New versus Repeat Visitors. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Willoughby, J.F. Examining cultural identity and media use as predictors of intentions to seek mental health in-formation among Chinese. Asian J. Commun. 2018, 28, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Beyond authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Rundel-Thiele, S. The brand loyalty life cycle: Implications for marketers. J. Brand Manag. 2005, 12, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Lam, C.F. Entertainment Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J.E.; Cook, D.A. Using Race and Culture in Counseling and Psychotherapy: Theory and Process; Allyn & Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 217 | 54.25% |

| Female | 183 | 45.75% |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 100 | 25% |

| 26–35 | 151 | 37.75% |

| 36–45 | 76 | 19% |

| 46–55 | 42 | 10.50% |

| 56–65 | 28 | 7% |

| 66 or above | 3 | 0.75% |

| Education | ||

| Middle school or below | 21 | 5.25% |

| High school | 62 | 15.50% |

| Junior college | 90 | 22.50% |

| Undergraduate | 200 | 50% |

| Postgraduate or above | 27 | 6.75% |

| Monthly Income (RMB) | ||

| 5000 or below | 169 | 42.25% |

| 5000 to 10,000 | 173 | 43.25% |

| 10,001 to 20,000 | 50 | 12.50% |

| 20,001 or above | 8 | 2% |

| Times of watching Cantonese opera per year | ||

| 1 to 3 | 260 | 65% |

| 4 to 6 | 76 | 19% |

| 7 to 9 | 34 | 8.50% |

| 10 to 12 | 19 | 4.75% |

| 13 or above | 11 | 2.75% |

| Variables & Measured Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI_Clarity | 0.77 | 0.868 | 0.686 | |

| I have clear sense of Cantonese opera culture background. | 0.865 | |||

| I understand pretty well what Cantonese opera culture means to me. | 0.843 | |||

| I have a strong sense of belonging to Cantonese opera culture. | 0.775 | |||

| CI_Pride | 0.717 | 0.84 | 0.636 | |

| I am happy to be a member of Cantonese opera culture. | 0.833 | |||

| I feel good about Cantonese opera culture. | 0.81 | |||

| I am pride in group of Cantonese opera culture. | 0.748 | |||

| CI_Engage | 0.927 | 0.945 | 0.774 | |

| I have often talked to other people in order to learn more about Cantonese opera culture. | 0.836 | |||

| I have spent time trying to find out more about Cantonese opera culture, such as its history, traditions, and customs. | 0.894 | |||

| I have often done things that will help me understand the Cantonese opera culture better. | 0.901 | |||

| I participate in cultural practices of Cantonese opera. | 0.91 | |||

| I active in organisations of Cantonese opera culture. | 0.856 | |||

| Perceived value | 0.862 | 0.907 | 0.709 | |

| Watching Cantonese opera is worthy. | 0.849 | |||

| The price of watching Cantonese opera is worthy. | 0.771 | |||

| Compared to the time I spend, watching Cantonese opera is worthy. | 0.868 | |||

| Compared to the efforts I made, watching Cantonese opera is worthy. | 0.876 | |||

| Satisfaction | 0.842 | 0.905 | 0.76 | |

| Watching Cantonese opera was one of the best leisure activities I have ever participated. | 0.864 | |||

| My experience of watching Cantonese opera was exactly what I needed. | 0.884 | |||

| I am overall satisfied with watching Cantonese opera. | 0.867 | |||

| Loyalty | 0.895 | 0.934 | 0.826 | |

| Price is not an important factor in my decision to watching Cantonese opera. | 0.893 | |||

| I would encourage friends and relatives to watch Cantonese opera related leisure activities. | 0.884 | |||

| I would say positive things about watching Cantonese opera to other people. | 0.948 |

| Variables | CI_Clarity | CI_Engage | CI_Pride | Loy | Val | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI_Clarity | 0.828 | |||||

| CI_Engage | 0.707 | 0.88 | ||||

| CI_Pride | 0.529 | 0.497 | 0.798 | |||

| Loy | 0.525 | 0.614 | 0.459 | 0.909 | ||

| Val | 0.544 | 0.545 | 0.649 | 0.561 | 0.842 | |

| Sat | 0.578 | 0.7 | 0.648 | 0.625 | 0.692 | 0.872 |

| Variables | CI_Clarity | CI_Engage | CI_Pride | Loyalty | Perceived Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI_Engage | 0.836 | ||||

| CI_Pride | 0.694 | 0.585 | |||

| Loyalty | 0.632 | 0.673 | 0.56 | ||

| Perceived value | 0.665 | 0.609 | 0.809 | 0.636 | |

| Satisfaction | 0.717 | 0.792 | 0.821 | 0.717 | 0.81 |

| Variables | Perceived Value | Satisfaction | Loyalty |

|---|---|---|---|

| CI_Clarity | 2.184 | 2.23 | |

| CI_Engage | 2.088 | 2.173 | |

| CI_Pride | 1.449 | 1.88 | |

| Perceived value | 1.988 | 1.918 | |

| Satisfaction | 1.918 |

| Hypotheses | β | Standard Error | T Values | p Values | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: CI_Clarity -> Val | 0.151 | 0.064 | 2.343 * | 0.019 | Yes |

| H1b: CI_Pride -> Val | 0.466 | 0.043 | 10.787 *** | 0.000 | Yes |

| H1c: CI_Engage -> Val | 0.207 | 0.061 | 3.377 ** | 0.001 | Yes |

| H2a: CI_Clarity -> Sat | −0.022 | 0.048 | 0.447 | 0.655 | No |

| H2b: CI_Pride -> Sat | 0.247 | 0.047 | 5.243 *** | 0.000 | Yes |

| H2c: CI_Engage -> Sat | 0.422 | 0.046 | 9.114 *** | 0.000 | Yes |

| H3: Val -> Sat | 0.313 | 0.053 | 5.955 *** | 0.000 | Yes |

| H4: Val -> Loy | 0.248 | 0.057 | 4.335 *** | 0.000 | Yes |

| H5: Sat -> Loy | 0.453 | 0.053 | 8.483 *** | 0.000 | Yes |

| Variables | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|

| Loyalty | 0.419 | 0.344 |

| Perceived value | 0.493 | 0.346 |

| Satisfaction | 0.657 | 0.494 |

| Path | β | Standard Error | T Values | p Values | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI_Clarity -> Perceived value -> Loyalty | |||||

| 0.037 | 0.018 | 2.068 * | 0.039 | YES | |

| CI_Engage -> Perceived value -> Loyalty | |||||

| 0.051 | 0.022 | 2.365 * | 0.018 | YES | |

| CI_Pride -> Perceived value -> Loyalty | |||||

| 0.116 | 0.028 | 4.17 *** | 0.000 | YES | |

| CI_Clarity -> Satisfaction -> Loyalty | |||||

| −0.01 | 0.022 | 0.449 | 0.653 | NO | |

| CI_Engage -> Satisfaction -> Loyalty | |||||

| 0.191 | 0.034 | 5.592 *** | 0.000 | YES | |

| CI_Pride -> Satisfaction -> Loyalty | |||||

| 0.112 | 0.023 | 4.818 *** | 0.000 | YES | |

| CI_Clarity -> Perceived value -> Satisfaction -> Loyalty | |||||

| 0.021 | 0.011 | 2 * | 0.046 | YES | |

| CI_Engage -> Perceived value -> Satisfaction -> Loyalty | |||||

| 0.029 | 0.01 | 2.839 ** | 0.005 | YES | |

| CI_Pride -> Perceived value -> Satisfaction -> Loyalty | |||||

| 0.066 | 0.016 | 4.212 *** | 0.000 | YES | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Luo, J.M.; Lai, I.K.W. Construction of Leisure Consumer Loyalty from Cultural Identity—A Case of Cantonese Opera. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041980

Yang J, Luo JM, Lai IKW. Construction of Leisure Consumer Loyalty from Cultural Identity—A Case of Cantonese Opera. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041980

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jian, Jian Ming Luo, and Ivan Ka Wai Lai. 2021. "Construction of Leisure Consumer Loyalty from Cultural Identity—A Case of Cantonese Opera" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041980

APA StyleYang, J., Luo, J. M., & Lai, I. K. W. (2021). Construction of Leisure Consumer Loyalty from Cultural Identity—A Case of Cantonese Opera. Sustainability, 13(4), 1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041980