Abstract

Recently, the construction industry has seen an increase in construction program level projects in which a number of projects are carried out simultaneously. These projects thus require more systematic management than traditional management methods due to both their complexity and the diverse stakeholders involved. When multiple projects overlap at the same time, it can create a gap between the contractor’s results and the user’s expectations at the closure phase of the construction program. These can include situations such as when handover is delayed, conflicts and frictions occur, and complaints from users mount. Therefore, an approach is needed to increase user satisfaction at the program level. This study presents a systematic closing management plan to increase user satisfaction for a smoother handover at the closure phase. The closure process was identified through case studies of activities in the closure phase. In addition, after identifying the stakeholder groups participating in the closure phase, responsibilities and roles were proposed as RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed) models by mapping the closure phase of processes and stakeholders. This model shows who is responsible and accountable for, consulted on, and informed about work processes in the closure phase of the program. From a user’s point of view, program closure signifies the beginning of operation and maintenance. We intend to contribute to the increase of user satisfaction by suggesting when and in what work activities the user will be involved in construction products from the user’s perspective.

1. Introduction

Recent construction projects are characterized by large scale, long construction periods, and a conflict of complex interests between project participants. In particular, there has been a growing number of program-level construction projects in which multiple projects are carried out at the same time, such as the USFK base relocation program, the Multifunctional Administrative City construction project in Korea, the Saemangeum Project, the Daegu Gyeongbuk Integrated New Airport relocation project, and various Smart City projects.

Globally, large-scale construction projects are changing from being part of a project-oriented industry to a program industry [1]. A program is defined as related projects, subsidiary programs, and program activities managed in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually [2].

The CHAOS report (2015), released by the Standish Group, showed that in 2015, the success rate of projects completed on time and within budget was 36%; however, the success rate at the program level, which includes construction products, processes, and customer satisfaction, was 29%, 7% lower. In addition, the success rate of small projects was 62%, while that of large projects was only 6% [3]. Accordingly, the US Federal Government (2016) put the Program Management Improvement and Accountability Act into effect in order to promote collaboration, improve decision-making, and reduce risk in large-scale construction projects such as infrastructure development and construction projects [4].

Meanwhile, 30% of the projects studied by FMI (2017) struggled with project closeout, including startup, commissioning, O&M (Operation and Maintenance), and training [5]. This is because, compared to the initial phase of the project, the closure phase lacks systematic work processes, and problems are solved by relying on the empirical knowledge of senior managers rather than setting and promoting roles and responsibilities [6].

In addition, as the closure phase approaches, user satisfaction decreases due to a divergence between the contractor’s results and the user’s expectations [7]. Furthermore, in the program closure phase, when a number of projects are completed simultaneously, handover is delayed and user complaints rise as participating personnel leave the site. Thus, problems often remain unsolved due to interface issues between the projects and differences of opinion between the constructors and the users [8].

In order to increase user satisfaction, it is necessary to approach construction and maintenance in an integrated manner from the perspective of the entire life cycle of construction products rather than to approach them in a segmented manner.

To date, Korea’s construction industry has focused on the development of construction phase work. Therefore, the level of hardware technologies in the construction stage is 80–90% of that of advanced countries, while that of software technologies in the preconstruction phase (to which planning and feasibility study and design belong) and in the postconstruction phase (including commissioning, handover, and maintenance) is 40–60% compared to advanced countries [9]. Recently, in the field of research, various attempts have been made to create more value at the preconstruction phase [10]; however, there is a lack of studies on business functions at the post construction phase.

In this regard, this study seeks to derive the work processes to be performed at the closure phase and then to identify the responsibilities and roles of stakeholders for each process for contribution to the successful closure of the construction program.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Construction Program

A construction program supports users to achieve benefits as one program that includes several individual projects, and it involves managing overlap or mutual interference that may arise during the execution phase of a project to successfully achieve the goal of the entire program [2,11].

Construction program management is a series of specialized construction management practices that applies to one or more capital building programs from start to closure [12] and is applied to the integrated management of various aspects of the construction process (program development, design, procurement, construction, activation, and operation and maintenance) to provide each project with standardized technologies and management expertise [11,13].

The characteristics of the construction program include multiple projects, rotation and repetition, continuous refinement, serial builders, similarities, standard process and product, standard human participation, and partnership facilitation [1].

Recently, as large-scale capital has been invested in the government and the public sector, and clients demand a wider range of services, the application of the construction program method has been expanded. In addition, various and innovative project management methods, such as Project Management Consultancy or Project Management Company (PMC), Public Private Partnership (PPP), Pre-construction (Precon), Early Contractor Involvement (ECI), CM (Construction Management) at Risk, and Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) have been discussed in connection with the program management.

2.2. Program Life Cycle and Closure Phase

2.2.1. Project Life Cycle and Closeout Phase

The life cycle of a project can be divided into various categories depending on the industry sector, project size, and complexity. In general, a project life cycle consists of four phases: initiation, organization and preparation, execution, and closeout.

Table 1 compares the project life cycles of eight organizations. The comparison results show that a project life cycle varies slightly in the names of stages according to national standards, but its phases are commonly divided into concept, planning, construction, delivery, and closeout. This study focuses on the closeout phase. In order to successfully carry out the work in the closeout phase, activities that systematically establish a closeout plan at the planning phase can be taken into account. However, these were excluded from the research scope of this study because most of the studies so far have focused on the key success factors of the overall construction project at the planning phase rather than on practical research regarding specific processes at the closeout phase [14,15,16,17,18].

Table 1.

Comparison of project life cycle.

It has been frequently reported that insufficient planning for closeout work often leads to delays in the handover and construction schedule delays; this, in turn, results in failure to achieve project goals [5,6,7,8].

2.2.2. Program Life Cycle and Closure Phase

In general, the closeout phases of multiple projects overlap at the closure of the construction program. Therefore, more detailed and more comprehensive plans are required than the closeout phase of one project. Unlike projects, programs are often run over long periods of time, sometimes even decades. The program life cycle is the sequence of phases from the time at which the program starts (or the agreed start-date for the program) to the time at which the program closes (or the officially agreed program end-date) [27].

There are relatively few definitions of the program life cycle.

As shown in Table 2, PMI divides the phases of the program life cycle into definition, delivery, and closure phases [2], and Thiryhas classified them into definition, development, and closure phases [28]. In addition, Gower divided them into initiation, delivery, and closure [29]; MSP divided them into program identification, definition, tranches management, and closure [30].

Table 2.

Comparison of program life cycles.

CMAA divides the life cycle of the construction program into five phases: program development, design, procurement, construction, and postconstruction [12]. The program development process includes such work activities as the organization of a program management team, program management plan, program management office, and information management system. In addition, the activities of design, procurement, and construction consist of the formation of an organization, design code development, design, construction contract package development, quality control, cost management, process management, information management, on-site facility provision, coordination and communication, program progress management, design change, and claims management. The workactivities of the postconstruction phase include program completion, program and project interfaces, maintenance, handover, facility management, administrative closure, and program evaluation.

In the program-related standards for each nation, most of the program life cycles are classified into three phases. In this study, the phases of the program life cycle are divided into definition, delivery, and closure, considering the cases in Table 2. The outline of each phase is as follows.

The program definition phase approves the program and provides the high-level strategic objectives of the program; the program delivery phase consists of activities performed to produce the intended outcome of each process, according to the program management plan. In addition, the program closure phase includes activities required to transfer the program benefits to the organization in charge of operation and maintenance and to officially close the program [2].

2.2.3. Difference between Project and Program Closure Phases

The program contains more components than required at the individual project level, and the life cycle of a program goes through three phases (program definition, delivery, and closure) to implement the program [5,28,29].

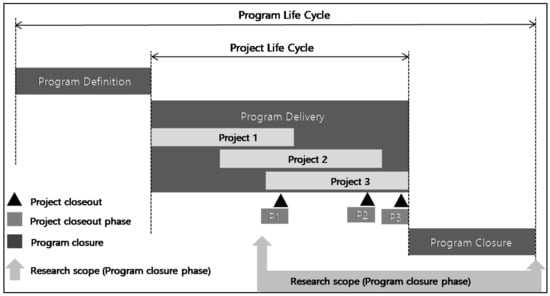

Figure 1 shows that the program closure process is performed after the program delivery phase. However, in practice, an individual project is closed out in the program delivery phase, and the project closeout is supported at the program level [2]. Therefore, the scope of this research (program closure phase) is from P1, which is one of the project closeout phases, to Program Closure.

Figure 1.

Project and program life cycle (adapted from APM2012).

Furthermore, program closure means another start of the use and operation phase from the user’s perspective [31]. Thus, it is necessary to transit the construction product to the user after construction (in accordance with the program objectives), minimize discomfort at the stage of building use, and ensure safe facility use [32]. However, in reality, the closure process is not often performed properly in the field, and closure phase work has relied on a rule of thumb approach due to a lack of research on the program closure phase. Karna noted that in the latter half of construction projects, the maintenance manual and handover are not carried out appropriately, resulting in a decrease in user satisfaction [33,34].

2.3. Responsibility Assignment Matrix Analysis Techniques

If the responsibilities and roles in the closure phase are not clearly identified between the various stakeholders of the program, this can have a negative impact on outcomes. Thus, there is a need to assign responsibility and roles during the work process, from the initiation phase of a project to the closure phase. In this study, the RACI matrix, a kind of responsibility assignment matrix (RAM), is used as a tool. RACI is an acronym derived from four responsibilities: responsible, accountable or approval, consulted, and informed [35].

The person that is assigned “Responsible” is the one who performs the work and is responsible for the task. “Accountable” is assigned to the person who has the final authority and is accountable for the task. “Consulted” individuals are several persons who are asked for advice and assist in the activity through communication during the course of work activities. “Informed” individuals are people who keep an eye out for updates on the progress and results of work activities.

3. Research Framework

3.1. Research Targets and Methods

This study attempts to define tasks to be performed at the program closure phase to minimize discomfort for users. In this regard, it contributes to improving satisfaction among facility users and operators. For this, data was collected from project participants at the closure phase of the construction program, including facility users.

Data collection was carried out in three steps. The first step investigates the closure phase process. In this manner, a literature review was conducted regarding closure phase processes and activities defined in the project, as well as program management guidelines for various organizations. The second step proceeds with case studies on the stakeholders at the program closure phase. The third step examines the responsibilities and roles of stakeholders in the closure phase work process.

3.2. Research Framework

In this study, it is assumed that the identification of the work process at the closure phase and the definition of roles and responsibilities among participants can contribute to the successful closure of the construction program. This chapter describes a framework for RACI model development to successfully close the construction program. The RACI model is used to determine how much responsibility a stakeholder bears for his role [19,32]. The distribution of roles and responsibilities among participants is important in project management [24]. However, the allocation of roles and responsibilities is even more important for a program in which more participants are involved as more complex and multiple projects overlap at the same time.

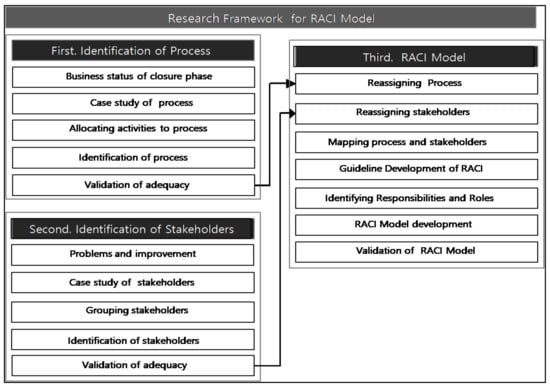

The development of the RACI model for a program is divided into three stages. The first stage is to derive processes and activities at the closure phase of the construction program. Standard processes and activities are derived from a comparative analysis of the closure phases of various cases. Adequacy and practical applicability are validated by in-depth expert interviews on the derived process. The second stage is to derive stakeholders at the program closure phase. The cases of stakeholders at the program closure phase are examined to identify the stakeholders of the closure phase at the program level. In order to derive the stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities, the mutual importance between the stakeholders was analyzed using the power/interest matrix, and the adequacy was then validated. The third stage is to develop the RACI model by mapping the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders for each activity at the closure phase. Defined activities and stakeholders are mapped to derive the roles and responsibilities for each activity. The adequacy and practical applicability of the RACI model were validated through expert interviews, and the guideline for practical application was then proposed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research framework.

4. Process Identification of Closure Phase

Implementing the program is a lengthy process, and, thus, uncertainties often exist due to environmental changes. Therefore, in order to minimize uncertainty, the process at the program closure phase needs to be identified during the earlier stages of the project, and the program should be carried out by the process on a systematic basis [36].

This chapter seeks to prescribe activities and work processes of the closure phase using the case studies, reorganize and categorize activities according to the process, and then confirm the closure phase activities and work processes through expert validation.

4.1. Case Studies of Work Processes at the Closure Phase

In order to derive the closure phase work processes and activities, this study investigated six cases: four domestic Korean cases (the Construction Management guideline by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MOLIT); the case analysis by the Construction Management Association of Korea (CMAK); Korea Land and Housing Corporation (LH) guidelines; the Yongsan Relocation Program (YRP)) and two overseas cases (the US Department of Defense (DoD) and the US Department of Energy (DOE)).

This study first examined the postconstruction stage, which can be viewed as the closure phase in the construction management guidelines announced by MOLIT. Five tasks (review of a comprehensive commissioning plan and commissioning confirmation, review of facility maintenance guidelines, selection of a facility management company, review of a facility handover plan, and warranty support) are suggested as relevant activities [8,26].

This study also analyzed the public announcement of CM ability valuation by the CMAK. The postconstruction stage work activities executed at the actual site were carried out in the following order: facility handover plan review, comprehensive commissioning plan review, facility maintenance guideline review, and warranty support. In the case of a construction management company, the selection of a facility maintenance company was a low priority; higher priorities were given to such tasks as project settlement support, operation and support work, housing occupancy support, final project management report, and defect management [37].

LH, which carries out many large-scale projects in Korea, has developed and utilized more than ten construction-management-related guidelines to maximize customer satisfaction in the construction sector. The guideline for construction completion and postmanagement describes the matters required to perform tasks at the completion and handover phases. This guideline was found to present a more specific methodfor performing closure phase tasks [38,39]. Completion phase activities include the closeout meeting of as-built drawings, operation and maintenance training, commissioning, prefinal and warranty inspections, contractual closure inspection, facility handover (handover of spare parts/tools and keys), warranty inspection, and construction evaluation.

The Yongsan Relocation Program (YRP), which is undertaken by construction program management in Korea, complies with the construction program completion procedures of the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Far East District (FED). The activities at the closure phase include Red Zone meetings, deficiency correction, prefinal inspection, final inspection, financial closure, commissioning, handover of keys, maintenance manual, lessons learned, review of warranty plan, and coordination for closure [40]. The program management process of the DoD was also investigated. In the process, closure meetings, contractor’s quality inspection, requirements adjustment, facility and equipment installation, and maintenance manual preparation, and training were carried out as the activities of the program closure phase [41].

DOE has performed the contractor’s punch list completion, handover of as-built drawings, LEED certification, furniture and equipment installation, commissioning, lessons learned, operation and management plan review, and user training as activities at the program closure phase [42].

4.2. Identification of Closure Phase Activities

The closure phase activities defined in the guidelines for the project and program management of various organizations at home and abroad vary in their scopes and names and are summarized in Table 3. In the summary process, items with the same and similar names of activities from the six guidelines and cases were integrated, and all activities included in a single case were integrated as well.

Table 3.

Activities in the closure phase of six cases.

In order to verify whether the comprehensive activities were properly selected, in-depth interviews with 49 experts who have carried out or are currently performing a construction program were conducted from February to April 2019. The respondents consisted of clients (45%), contractors (16%), and program managers (39%). Of these, 14% of them had work experience of less than 10 years, 39% 10~20 years, and 47% more than 20 years, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Information of respondents (n = 49).

The experts were presented with 30 activities and asked whether the activities that were necessary to achieve the goal of “successful implementation of the construction program closure phase” had been appropriately selected and whether there are any items to be added, deleted, or integrated.

As a result of the interview, 30 activities were reestablished after insignificant items were deleted (1 case), items that were duplicated or required to be renamed were changed (9 cases), and additionally required items were added (10 cases). The ten additional (CP 31~40) activities included checklists at the closure phase, real estate documents, and communication affecting the closure schedule, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Identified and adjusted activities at the closure phase.

4.3. Reorganization of Closure Phase Processes

The 30 adjusted activities were grouped into a smaller number of processes. For grouping, reclassification was made after a comparison among the CMAA closure phase process [12], the closure phase process of Delaney [43], and the YRP closure phase processes [44].

As a result of the comparison, 12 of the 24 processes that overlapped in the 3 documents were integrated into 9 processes, and the remaining 12 were reclassified as activities with a lower hierarchy level, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Reclassifying closure process.

Among the 24 processes, those that were integrated into 9 categories from A to I are indicated in uppercase letters, and those absorbed by subprocesses are indicated in lowercase letters (a~i).

4.4. Categorization of Activities for Each Process

The 30 activities selected in this study were categorized based on the 9 processes at the closure phase [45]. Two to six activities were allocated for each process in Table 7.

Table 7.

Allocating activities to processes.

The program closure phase begins from the closeout meeting (A) process. In this process, the tasks of reconfirming the user’s requirements, the interface of the stakeholders, and the checklist of the closeout meeting are checked so as to discuss the closure procedure. In addition, the expected schedule is reconfirmed so that each process and activity can be addressed in a timely manner. The closeout meeting continues until all tasks, such as unsolved matters or cooperation matters for closeout, are completed.

The process of the contractor’s internal completion inspection and punch-out inspection is the substantial completion (B) process. In this process, the contractor creates a punch list and carries out quick corrections in order to complete the construction as scheduled. The contractor’s punch-out inspection must be corrected prior to the prefinal inspection.

The commissioning (C) process begins upon approval after the completion of all relevant tasks and the submission of all required inspection reports and operation and maintenance manuals. Energization of electricity, a functional performance test, testing, adjusting, and balancing are all completed prior to the contractor’s own final inspection; a deficiency ensures inspection. A report on the results is then submitted.

In the final inspection (D), prefinal inspection and final inspection activities are carried out. The user is present to check whether their requirements are related to construction defects. If the defect requires corrective work in accordance with the contract provisions, the contractor is notified to take action. All these matters must be completed prior to handover.

The maintenance management (E) manual contains all data related to the operation and maintenance of all mechanical, electrical, and building systems provided under the contract. In the maintenance management process, operation and maintenance plans and manuals are prepared by the contractor to provide training to users. The contractor establishes and examines the warranty management plan and performs warranty inspection for identified defects after the completion of construction.

The handover (F) process is to hand over to the user the preparation of the handover plan, as-built drawings, building permit and completion approval, preparation of real estate-related documents, the submission of various test result reports, and keys and spare parts.

The activation (G) process communicates the factors influencing user occupancy adjustment, furniture and equipment installation, operation testing, relocation and moving, operation of facilities such as electrical systems and fire-fighting equipment, and the schedule.

In the program evaluation (H) process, user satisfaction evaluation, program performance, and construction evaluation are carried out.

In the program closure (I) phase, the program is closed by carrying out contractual, financial, and administrative closure, personnel reassignment, the lessons-learned register and transition, and the finalization of claims.

4.5. Expert Validation

Expert interviews were conducted on 9 processes and 30 activities at the proposed construction program closure phase. During the expert interviews, a quantitative evaluation through a questionnaire was performed as the first step, and a qualitative evaluation was performed through an interview as the second step. A total of 12 experts were selected from a pool of clients, contractors, and program managers.

First, the quantitative evaluation was done on a 5-point scale: 5 points (very adequate), 4 points (adequate), 3 points (normal), 2 points (inadequate), and 1 point (very inadequate). In the second step, qualitative opinions were collected through in-depth interviews from each stakeholder.

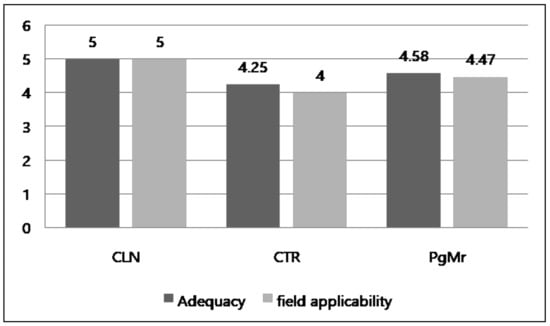

4.5.1. Adequacy and Field Applicability

As shown in Figure 3, the adequacy and field applicability on closure phase work processes and activities received 5 points from the client group, who answered that the definition and categorization of the work process at the closure phase were well-reflected. On the other hand, adequacy and field applicability were given points ranging from 4.47 to 4.58 from the program manager group, who responded that the closure phase process was properly defined but that other activities, such as the operation and maintenance study and integrated commissioning test activity, in addition to the proposed work process, can be considered at the closure phase to maintain construction products in an appropriate state. The contractor group gave relatively low scores (ranging from 4 to 4.5 points) and responded that the business processes and activities at the closure phase were generally well defined, but some activities may not be within the scope of the contractor’s work, depending on the scope and method of the contract between the client and the contractor. Moreover, it was reported that an increase in costs should be considered to perform all 30 activities.

Figure 3.

Validation of adequacy and field applicability.

In conclusion, the categorization of 9 processes and the definition of 30 activities were found to be somewhat regrettable from the perspectives of program managers and contractors. However, taken as a whole, they are acceptable.

4.5.2. Interviews on the Results

The closure phase work process proposed in this study should be applicable to all stakeholders carrying out construction programs. Accordingly, additional interviews were conducted by dividing the stakeholders into groups of clients, contractors, and program managers. The client group suggested that the business process be established on a systematic basis, but the active involvement of users is required for the smooth handover at the program closure phase. Therefore, it is ascertained that there is a need to investigate how important the user is at the closure phase.

The contractor group responded that successful closure would be possible if the closure phase was carried out according to the processes and activities proposed in this study. However, the group also mentioned the limitations that arise from the need for continuous allocation of dedicated personnel until the closure of the program in order to perform all processes and activities. Therefore, it is judged that there will be a need to establish roles and responsibilities for each process at the closure phase.

The program manager group responded that a withdrawal of manpower is inevitable due to personnel reassignment and workload reduction at the program closure phase; it would be possible to efficiently allocate human resources when establishing roles and responsibilities for the work processes and activities at the closure phase.

4.6. Subconclusion

For the successful closure of the construction program, this study proposes the closure phase processes and activities of the construction program after studying domestic and international cases and collecting opinions from people in charge of practical business affairs.

The major content of this study is summarized as follows.

First, 30 activities at the program closure phase were derived. Second, nine processes (closure meeting, commissioning, substantial closure, final inspection, maintenance, handover, activation, program evaluation, and program closure) required for the construction program closure phase were proposed based on the analysis of previous research and case studies. Third, two to six activities were categorized in each process at the closure phase.

Quantitative and qualitative evalidations were conducted through expert interviews on the proposed closure phase processes and activities. As a result, adequacy and field applicability can be confirmed through these interviews. In relation to the closure phase processes and activities proposed in this study, the clients mentioned the need for field application, but the contractors perceived the proposed activity as an additional task. However, most of the stakeholders agreed that the closure phase processes and activities should be applied earlier in order to facilitate and systematize the handover process at the closure phase.

5. Stakeholder Identification at Closure Phase

5.1. Definition of Stakeholder’s Responsibilities and Roles

The term stakeholder refers to any person, group, or institution that affects, or can be affected by, a decision, activity, or outcome of a project, program, or portfolio [2]. The identification of stakeholders is not only carried out at the program initiation phase; there may also be stakeholders who reveal their expectations at the closure phase [46]. Since various stakeholders participate in the construction program, it is necessary to define the responsibilities and roles of these stakeholders to make the program successful. However, as these responsibilities and roles become ambiguous, impulsive decisions often can be made by the director of the program during the carrying-out of activities at the program closure phase. Accordingly, responsibility, communication, and decision-making clarity are essential elements for successful program management.

Therefore, stakeholder importanceneeds to be estimated prior to the definition of roles and responsibilities among the stakeholders in order to assist the decision-making of the stake holders on the performance of the program.

5.2. Case Studies of Stakeholders at Closure Phase

This section defines the stakeholder group at the program closure phase based on the analysis of three cases: Incheon International Airport construction (the second phase construction project), which lasted seven years from 2002; Gyeongbu High-Speed Railway construction, which lasted nine years from 2002; the Multifunctional Administrative City construction, which has lasted 14 years since 2007. The stakeholders at the closure phase of such cases were identified and classified into four groups: client, program manager, contractor, and user, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Identifying stakeholders of case studies.

First, the clients are owners, employers, and government authorities such as the Incheon International Airport Corporation and the Korea Rail Network Authority.

Second, PgMr refers to an individual or a group such as consultants, engineers, consulting engineers, program managers, project managers, and general project managers such as P, B, and H company.

Third, contractors include subcontractors, construction companies andlegal contractors such as a general contractor.

Fourth, user means an individual or group such as an end-user or an operation manager. For example, the same client and user groups are present in Incheon International Airport construction, whereas the user is the Korea Railroad Corporation and the client is the Korea Rail Network Authority in the Gyeongbu High-Speed Railway construction project. In particular, the user group was not identified in the construction phase but emerged as a new stakeholder at the closure phase.

5.3. Stakeholder Importance

This section seeks to calculate the weight of stakeholders importance by considering the relative importance of stakeholders. Due to the characteristics of the construction program, as stakeholders pursue different values in a number of projects, they have different perspectives on the roles and responsibilities for closure phase activities.

Therefore, it is necessary to utilize the weights of the responsibilities and roles of each stakeholder at the closure phase. A questionnaire survey was conducted to examine the power and interest of the four groups of stakeholders on the processes and activities.

The survey period ranged from January to May 2020, and the subjects of the survey are 51 stakeholders: 15 clients (29%) with experience in program management, 11 program managers (22%), 12 contractors (24%), and 13 users (25%). The average length of service of the survey subjects was 15.8 years.

In order to estimate the stakeholders’importance, power (hereafter “P”) and interest (hereafter “I”) were evaluated on a 5-point scale for each stakeholder group.

To ensure the objectivity of the survey, stakeholders were asked to evaluate the power and interest of other stakeholders, excluding the group to which they belong. The survey results of the power and interest of stakeholders are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Survey results of power and interest.

The survey results showed that the power of stakeholders on the program was Pe~Pu, with an average of 4 points—the highest at 4.93 for the client and the lowest at 3.08 for the contractor. The interest of stakeholders was Ie~Iu, with an average of 4.3 points—the highest at 4.87 for the client and the lowest at 3.67 for the contractor.

The calculated stakeholders’power and interest scores were multiplied to obtain stakeholder importance. The equation for estimation can be represented as follows:

where SIi is stakeholder importance.

The survey results of stakeholder importance are summarized in Table 10. It was found that the client earned the highest weight of stakeholder importance with a score of 0.343, followed by the user with 0.256, the project managerwith 0.239, and the contractor with 0.162. These affected the processes and activities at the closure phase in the same order.

Table 10.

Results of stakeholder importance.

This importance can be used as a weight in the stakeholder’s opinion score when developing the responsibility and role model of stakeholders.

6. RACI Model for Process

This is to analyze who, what, and how to carry out the relevant processes in a transition from the closure phase to the maintenance phase. The RACI chart is a technique that is capable of managing responsibilities and roles simply and clearly by mapping the stakeholders for each process.

The criteria for allocating the RACI mapping of stakeholders for each process were established by referring to the RACI table of the MSP program closure phase [32] and the RACI matrix of the USFK Base relocation program. The responsibilities and roles of stakeholders for each process were assigned based on the criteria.

6.1. Establishment of Criteria for Stakeholders’ Responsibilities and Roles for Each Process

6.1.1. RACI Table of the MSP Program Closure Phase

The roles and responsibilities for seven flow steps at the closure phase of MSP were assigned to four stakeholder groups, as shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Typical responsibilities for closing a program (adapted from MSP 2011).

The program manager was found to be judged “Responsible” in five flow steps among the seven flow steps. The senior responsible owner was deemed “Accountable” in all seven flow steps. The business change manager was rated as “Consulted” in five flow steps and “Responsible” and “Informed” in one flow step each. The program office was assigned “Informed” in five flow steps and “Consulted” in two flow steps, respectively.

For the RACI of MSP, “Responsible” means getting the work done, and “Accountable” refers to being answerable for the program’s success. To be “Consulted” means someonewho provides support and has the information or capability required, and “Informed” refers to being notified but not consulted.

6.1.2. USFK Base Relocation Program’s Closure Phase RACI Matrix

The RACI matrix of the closure phase of the USFK Base relocation program is defined in the PM work guidebook for YRP construction management [44], as shown in Table 12.

Table 12.

Roles and responsibilities of YRP (adapted from YRP PM guidebook 2014).

In the program closure phase, stakeholders were divided into four groups: client (MURO, FED, LH), PMC, contractor, and user.

The client supervises the project management of the Program Management Consortium (PMC) and overall tasks related to construction management and project execution, provides documents on any nonconformities found in supervision to the PMC so that the contractor can take corrective actions, and can stop thetask until the nonconformity is corrected. The client also observes the work of the PMC to see if the construction project is carried out in accordance with the design documents and specifications within safety guidelines, a certain range and budget, and the life, health, safety, and security requirements. In addition, the client asks the PMC to submit the shop drawings and material sample/equipment deliverables for review and approval and examines them.

The PMC performs the CM work not only for overall program management but also for individual projects. It manages all matters related to commissioning and handover, including quality, schedule, and cost management. The PMC also runs a construction closure team in the program management consortium that dedicates itself to quality completion within a completion date and confirms the details of the handover process and construction completion of each project.

The contractor fulfills the contractual obligations in accordance with the principle of good faith, as stipulated in the contract document, the construction supervisor’s instructions, and related laws and regulations. The contractor also complies with the procedures of quality control, equipment, materials, and manpower management.

The user performs facility handover and management, participates in the closeout meeting, pre-inspection, and final-inspection at the closure phase, and manages the warranty and repair of the completed facilities.

6.1.3. Establishment of Criteria for Roles and Responsibilities

The criteria for roles and responsibilities were established on the basis of the case studies of the closure phase of the MSP and USFK Base relocation program, as shown in Table 13.

Table 13.

Setting of criteria of roles and responsibilities.

6.2. Expert Interviews on Responsibilities and Roles of Stakeholders

A survey of experts with experience in construction programs was carried out to develop the RACI model of stakeholders for each activity at the closure phase. Since the stakeholders have conflicting interests in the closure of the program, the opinions from clients, program managers, contractors, and users were examined separately to ensure the objectivity of the survey.

For the survey, 100 emails were sent to experts with experience in construction programs; 56 provided answers between August and October 2020. The response rate was 56%, and the respondents were 15 clients (27%), 12 program managers (21%), 14 contractors (25%), and 15 users (27%).

The stakeholders are listed on the X-axis in the following order: clients, program managers, contractors, and users. The 9 processes and 30 activitiesof the closure phaseare listed on the Y-axis, and then, 1–4 points are allocated, as in Table 14. With respect to the roles and responsibilities for the activity, 4 points are given for the responsibility of completing the activity, 3 points for the approval of the activity, 2 points for cooperation and coordination, consulting, or support, and 1 point for information provided and being notified on the results.

Table 14.

RACI (responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed)description evaluation score.

The 56 people were divided into groups of stakeholders, and the average scores given from the stakeholders of each group are analyzed in Table 15.

Table 15.

Results of RACI chart survey.

Meanwhile, the weights calculated in Table 10 were reflected in the R, A, C, and I opinions of stakeholders for each activity. The assigned score ranged from 1.0 to 4.0 points. The RACI assignment was figured out with respect to four categories (R category, A category, C category, and I category) for responsibilities and roles, and the difference between the highest point and the lowest point was calculated using quartiles at 0.75. Thus, the RACI assignment criteria was selected as 3.25 < R ≤ 4.0, 2.50 < A≤ 3.25, 1.75 < C ≤ 2.50, and 1.0 < I≤ 1.75.

6.3. RACI Models Proposed for Each Process

The degrees of roles and responsibilities of stakeholders for processes and activities at the closure phase were derived, as summarized in Table 16. For example, the score for the client at the closeout meeting (a1) was calculated as the final value of the client obtained by calculating the sum of each client score in Table 15 and the weight in Table 10.

Table 16.

Developed RACI model.

In Table 16, the score of theclient is 2.55, which is the sum of the client’s 3.12 × 0.343 and the PgMr’s 2.86 × 0.239, the contractor’s 2.85 × 0.162, and the user’s 1.32 × 0.256, as assigned in Table 15. Since 2.55 is included in the range of 2.50~3.25, the a1 client value was determined as “Accountable”, as shown in Table 16.

The final RACI is shown in Table 16. It can be confirmed that the proposed closure phase RACI model meets all 26 criteria for responsibilities and roles at the closure phase in Table 13. The calculation results, according to the RACI allocation criteria, showed that in three activities of c1, f3, i4, “Responsible” was calculated for two parties. However, since only one person should be assigned as “Responsible” for the activity, the stakeholder with lower scores obtained was adjusted to “Accountable” [35].

6.4. Validation of RACI Model

The validation of the RACI model of stakeholders for each process was carried out in two stages. The first stage was a quantitative verification in which the score obtained from the quantified responsibilities and roles derived from Table 16 were compared with the relative importance of the stakeholders calculated in Table 10. In the second stage, in-depth interviews were conducted on those experts with experience in constriction programs. A total of 29 people were surveyed: 8 clients, 7 program managers, 6 contractors, and 8 users participated in the interviews.

6.4.1. Validation of Correlation between Stakeholder Importance and the Responsibilities and Roles

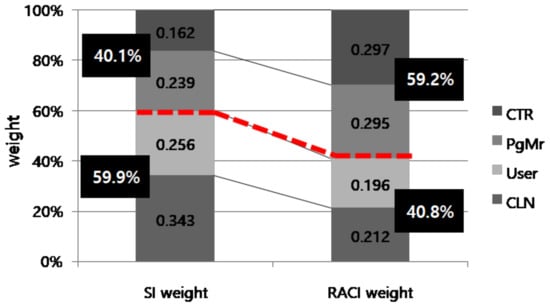

The correlation between stakeholder importance (SI) and the relative importance of each stakeholder of the proposed RACI model was validated in this study. It was assumed that the stakeholder has as much power and interest in the construction program as responsibility and role. Therefore, the SI weights calculated from Table 10 and the relative ratio of the combined RACI score for each stakeholder in Table 16 were calculated and compared with each other.

The stakeholder importance weight analyzed in Table 10 was the highest for the client (0.343), followed by the user (0.256), the program manager (0.239), and the contractor (0.162). However, the RACI weight analyzed in Table 16 was the highest for the contractor (0.297), followed by the program manager (0.295), the client (0.212), and the user (0.196), respectively.

As shown in Figure 4, the relative importance (SI = Power Index × Interest Index) of the program closure phase was 59.9% for the client and the user; this was 19.8% higher than the 40.1% for the program manager and the contractor. On the other hand, the responsibility and role for the closure phase process and activity was 40.8% for the client and the user, which was 18.4% lower than the 59.2% for the program manager and the contractor.

Figure 4.

Results of weight comparison of stakeholder importance (SI) and RACI.

In summary, the relative importance expressed by the power and interest of the client and the user on the construction program was as high as 59.9%, whereas the roles and responsibilities for each process and activity at the program closure phase was only 40.8%. This result suggests that the hypothesis that the stakeholder has as much power and interest in the construction program as responsibility and role is not established. In other words, although the client and the user have a relatively large influence on the successful closure of the program, they lack the corresponding responsibility and role.

Therefore, in order to minimize the gap between the SI weight and the RACI weight, special effort needs to be made to expand the responsibilities and roles of the client and the user at the closure phase.

6.4.2. Additional Opinions Regarding Research Results

With respect to the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders for each process at the closure phase, in-depth interviews were conducted with stakeholders. After the interview, the client group noted that the responsibilities of the stakeholder for each process on the RACI model proposed in this study were well established on a systematic basis. Meanwhile, there was another opinion: consultation from a third party is needed to coordinate conflicting opinions among stakeholders due to the limited time in the closure phase.

The contractor group responded that if the proposed RACI model is presented in the closure phase, the successful closure of the program will be possible. However, the contractor group added that the responsibilities and roles may vary depending on whether the activities of the program at the earlier stage (such as operation and program evaluation) are included in the scope or not. In the case of commissioning, the responsibilities may differ depending on whether the contract is made under the contractor’s responsibility or with a separate commissioning service company.

In the program closure phase, as the project is almost closed out, the withdrawal of most of the manpower is inevitable due to the reduced workload. In this context, the program manager group responded that the possibility of program success would be very high if the closure process is systematically operated from the beginning of the closure according to the proposed RACI model.

The user group responded that at the program closure phase, the opinions of users should be included in the results of the construction products, and the utilization of the proposed RACI model will be high as the roles and responsibilities are reasonably presented in a certain process at the closure phase. In addition, the user group offered an opinion that smooth communication with users at the closure phase will contribute not only to reducing additional work but also to saving initial maintenance costs in the maintenance phase.

7. Conclusions

Due to project complexity and various stakeholders, a divergence between contractors’ construction products and user expectations occurs. Therefore, to increase user satisfaction, to manage the closure phase systematically, and to handover the projects smoothly, research was conducted to derive closure phase work processes, activities, and stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities.

The main content of this study is summarized as follows. First, 9 processes and 30 activities were derived based on the case studies. The 9 processes are closure meeting, commissioning, substantial closure, final inspection, maintenance, handover, activation, program evaluation, and program closure. Second, the stakeholders involved in the closure phase were classified into four groups: the client, the program manager, the contractor, and the user. Third, the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders for the processes and activities to be carried out at the closure phase were identified and proposed as a RACI model. Fourth, the validation for the adequacy and applicability of the proposed model revealed that the client and the user have high power and interest at the closure phase, but they have relatively less responsibility and role in the activities performed at the closure phase. Therefore, it is ascertained that special effort needs to be made to expand the responsibilities and roles of the client and the user at the closure phase.

Meanwhile, this study poses some limitations in generalizing the research results because the range of the programs to be surveyed was limited. Moreover, the number of experts with experience in performing construction programs was small. Therefore, additional statistical analysis needs to be carried out based on an objective and sufficient number of samples through the application of the proposed model to more case studies.

To do this, the authors will conduct in-depth and detailed follow-up research from various perspectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-y.L. and C.-t.H.; methodology, W.-y.L. and S.-h.L.; validation, W.-y.L., C.J. and S.-h.L.; formal analysis, W.-y.L.; investigation, W.-y.L.; data curation, W.-y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-y.L.; writing—review and editing, S.-h.L., C.J.and C.-t.H.; visualization, W.-y.L.; supervision, C.-t.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (MOLIT)/the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA), grant number 1615011548.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| APM | Association for Project Management |

| CIOB | Chartered Institute of Building |

| CLN, CN | Client |

| CM | Construction Management |

| CMAA | Construction Management Association of America |

| CMAK | Construction Management Association of Korea |

| CTR, CT | Contractor |

| DoD | Department of Defense |

| DOE | Department of Energy |

| DPW | Directorate of Public Works |

| FAR | Federal Acquisition Regulation |

| FED | Far East District |

| FF&E | Furniture, Fixtures, and Equipment |

| FMI | Fails Management Institute |

| IPD | Integrated Project Delivery |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LEED | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| LH | Korea Land and Housing Corporation |

| MND | Ministry of National Defense |

| MOLIT | Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport |

| MSP | Managing Successful Programmes |

| MURO | MND USFK Relocation Office |

| PMI | Project Management Institute |

| PMC | Program Management Consortium |

| PRINCE2 | PRojects IN Controlled Environments |

| PgMr, PM | Program Manager |

| PMBOK | Project Management Body of Knowledge |

| PMO | Program Management Office |

| PPP | Public-Private Partnership |

| PVT | Performance Verification Test |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| RACI | Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed |

| RAM | Responsibility Assignment Matrix |

| RIBA | Royal Institute of British Architects |

| TAB | Testing Adjusting Balancing |

| USACE | US Army Corps of Engineers |

| USFK | United States Forces Korea |

| US | User |

| YRP | Yongsan Relocation Program |

References

- Thomsen, C.; Sanders, S. Program Management 2.0: Concepts and Strategies for Managing Building Programs; Construction Management Association of America: McLean, VA, USA, 2011; pp. 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- PMI. The Standard for Program Management, 4th ed.; PMI: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 3–14. Available online: http://dl.icdst.org/pdfs/files3/27b0e80bdf3bd39a8d8e69c08b5352da.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- The Standish Group. The Standish Group Report: Chaos; The Standish Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.projectsmart.co.uk/white-papers/chaos-report.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- United States Congress House. Committee on Oversight and Reform. Program Management Improvement Accountability Act, 114th Congress, 2nd Session. 2016. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1550 (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Spragins, B.; Dwyer, B.; Lee, E. What to Do When Projects Go Bad, Part 2; FMI Insights: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2017; p. 10. Available online: https://www.fminet.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/WhatToDoWhenProjectsGoBad_Part2_FIN.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Lee, W.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Cha, Y.H.; Hyun, C.T. A Suggestion of Process in the Construction Program Closure Phase. In Proceedings of the 2019 KICEM Conference; Korea Institute of Construction Engineering and Management: Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Cha, Y.H.; Hyun, C.T. Identification of Business Process in the Closure Phase of Construction Programs. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Furia, G.L. Project Management Recipes for Success, 1st ed.; Auerbach Publications: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement. General Report on Technical Level Analysis of Land, Infrastructure and Transport; Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement: Anyang-si, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.S.; Park, M.; Jeong, M.; Lee, I. Effect of Pre-Construction on Construction Schedule and Client Loyalty. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 10, 845–848. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgers, M. Owner Innovate Capital Programs through Program Management; Quarterly Issue 3; FMI: Denver, CO, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- CMAA. Construction Management Standards of Practice; CMAA Publications: McLean, VA, USA, 2015; pp. 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- CMAA. Program Management Procedure; CMAA Publications: McLean, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz, M.; Almuajebh, M. Critical Success Factors for Sustainable Construction Project Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoodi, A.I.; Khalilzadeh, M. Identification and Evaluation of Construction Projects’ Critical Success Factors Employing Fuzzy-TOPSIS Approach. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 1593–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Scott, D.; Chan, A.P.L. Factors affecting the success of a construction project. ASCE J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2004, 130, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Drew, D.S.; Ho, M. Critical success factors for stakeholder management: Construction practitioners’ perspectives. ASCE J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanvido, V.; Parfitt, K.; Guveris, M.; Coyle, M. Critical success factors for construction projects. ASCE J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1992, 118, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMI. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 6th ed.; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 354, 547–554. [Google Scholar]

- AXELOS. Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, 6th ed.; The Stationery Office (TSO): London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. ISO 21500, Guidance on Project Management; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- RIBA. RIBA Plan of Work; RIBA: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CIOB. Code of Practice for Project Management for Construction and Development, 5th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Association for Project Management (APM). APM Body of Knowledge, 6th ed.; Association for Project Management: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CMAA. Project Closeout Guideline; CMAA Publications: McLean, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Construction Technology Promotion Act; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport: Sejong, Korea, 2020.

- ISO. ISO 21503, Project, Programme and Portfolio Management—Guidance on Programme Management; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Thiry, M. Program Management; Gower Publishing Company: Aldershot, UK, 2015; pp. 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Lock, D.; Wagner, R. Gower Handbook of Programme Management; Gower Publishing, Ltd.: Aldershot, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, O. APM Research Fund Series: How Can We Hand over Projects Better. 2017. Available online: https://www.apm.org.uk/media/6153/handoverreport_2017_final.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- Thirion, C. Effective Handover of Projects to Operations Teams. 2018. Available online: https://www.ownerteamconsult.com/effective-handover-of-projects-to-operations-teams/ (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- Office of Government Commerce(OGC). Managing Successful Programmes; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 2011; pp. 177, 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Karna, S. Analysing customer satisfaction and quality in construction—The case of public and private customers. Nord. J. Surv. R. Estate. Res. 2004, 2, 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chanter, B.; Swallow, P. Building Maintenance Management, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.L.; Erwin, J. Role and Responsibility Charting (RACI); Project Management Forum (PMForum): Dubai, UAE, 2005; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Association of Japan (PMAJ). P2M: A Guidebook of Project & Program Management for Enterprise Innovation, Project Management Association of Japan; Project Management Association of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Korea CM Association. 2019 Construction Management Capability Assessment and Disclosure Data Collection; Korea CM Association: Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- LH. Construction Management Guideline for Yongsan Relocation Program; Korea Land and Housing Corporation: Jinju, Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Land and Housing Corporation (LH). Experience and Knowledge of the Yongsan Relocation Plan; Korea Land and Housing Corporation: Jinju, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of National Defense (MND). Program Management for USFK Base Relocation Project; Ministry of National Defense: Seoul, Korea, 2020.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. MILCON Project Closeout, The Red Zone Meeting; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Administrative Change to DOE G 413.3-16A, Project Completion/Closeout Guide; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Delaney, J. Construction Program Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of National Defense (MND). Program Management Work Guidebook for YRP Construction Management; MURO: Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, Y.W.; Kim, J.H.; Hyun, C.T.; Han, S.W. Development of a Program Definition Rating Index for the Performance Prediction of Construction Programs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T. Successful Project Management, 5th ed.; Koggan Page: London, UK, 2016; pp. 98–99. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).