COVID-19 Changed Human-Nature Interactions across Green Space Types: Evidence of Change in Multiple Types of Activities from the West Bank, Palestine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area and Pandemic Context

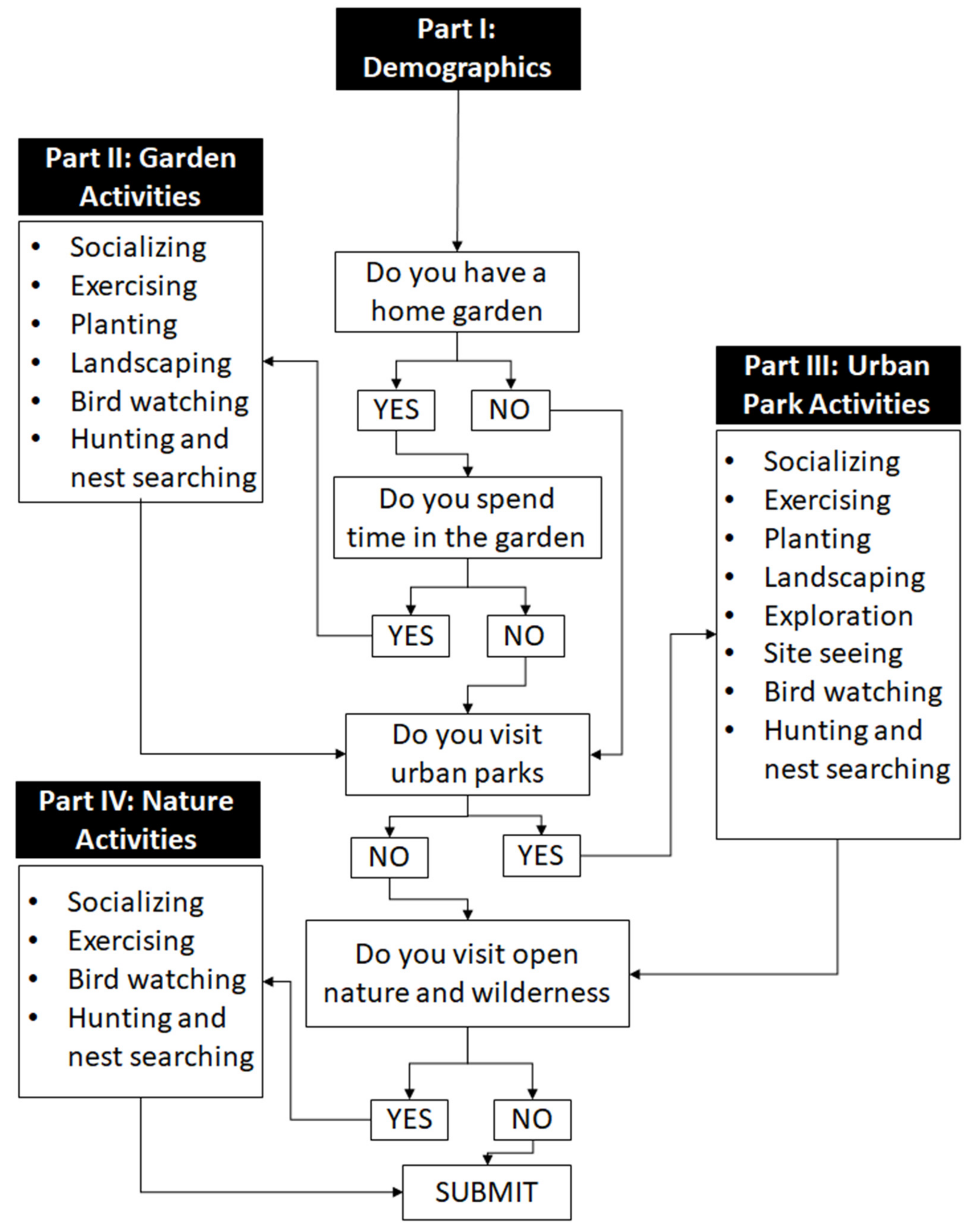

2.2. Survey Design and Implementation

2.3. Representativeness of the Sample

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

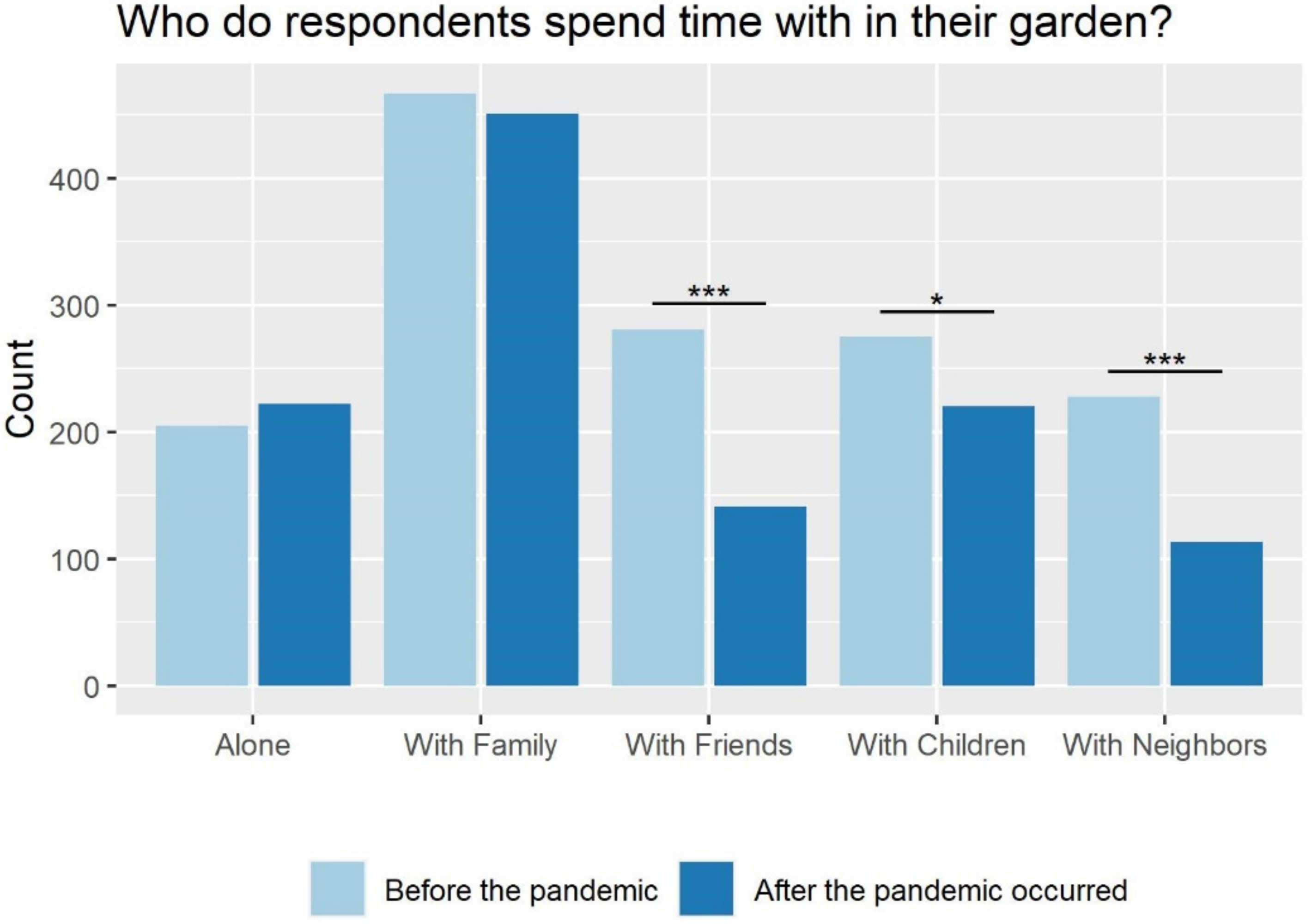

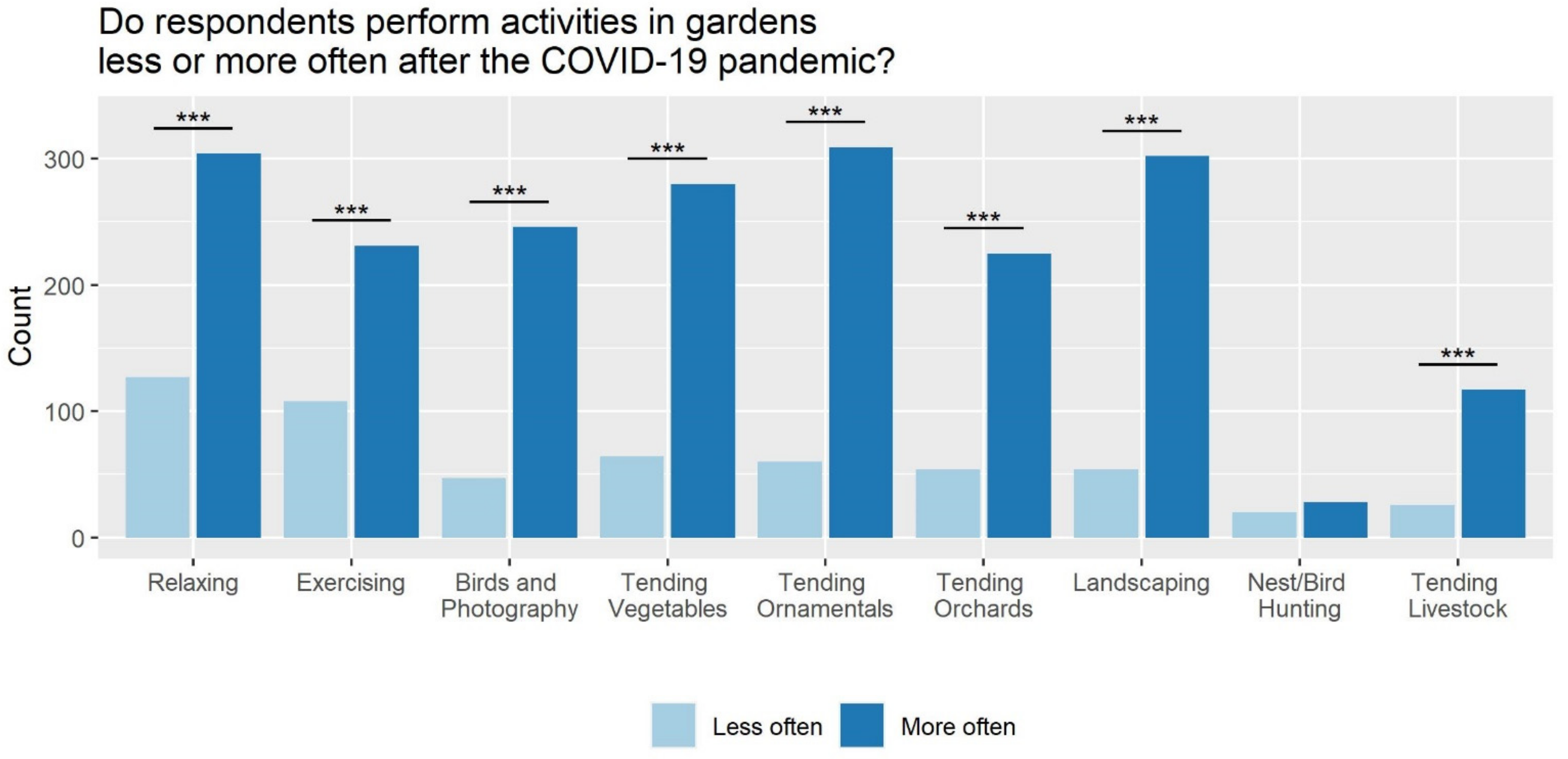

3.1. Gardens (Private Green Spaces)

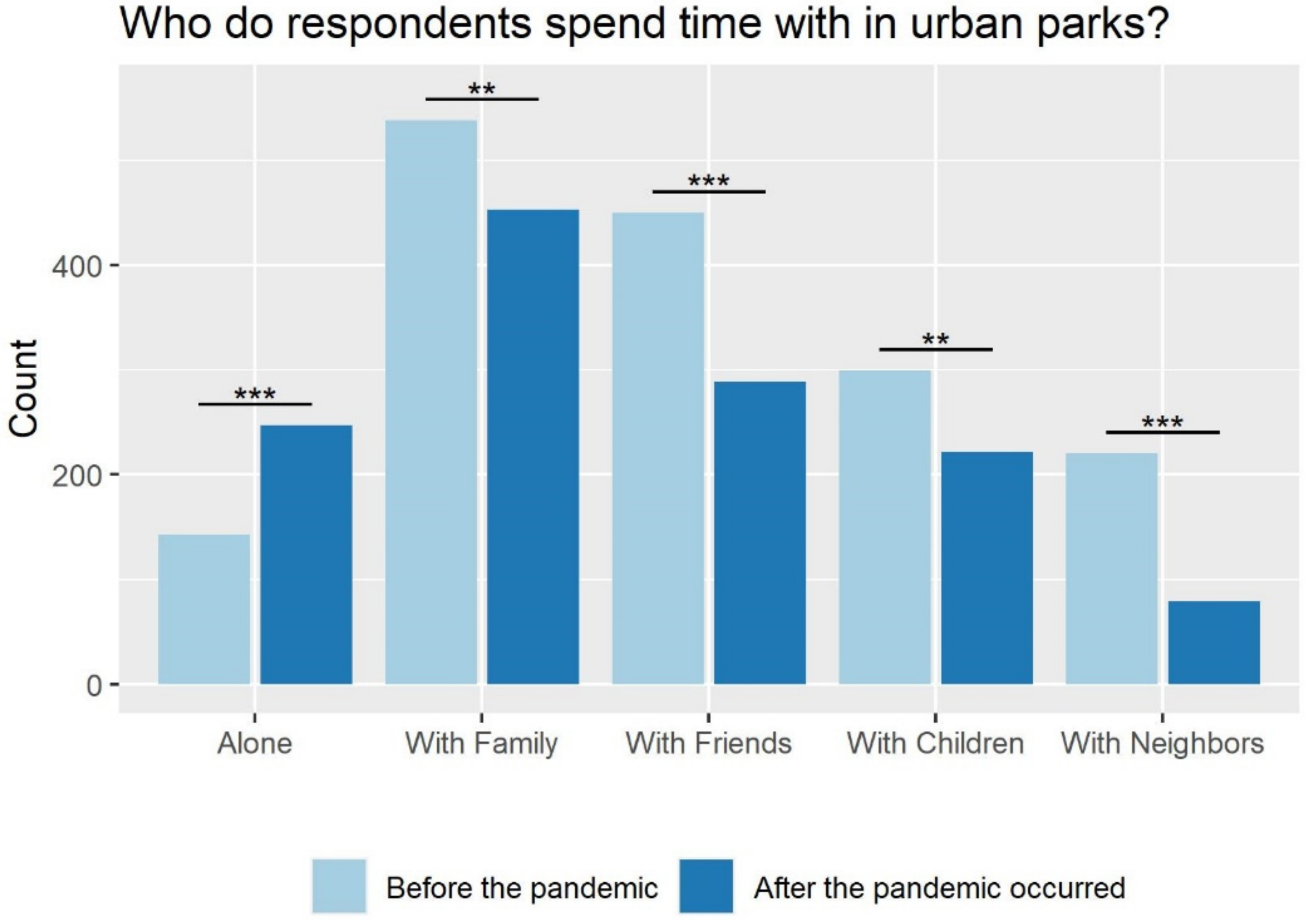

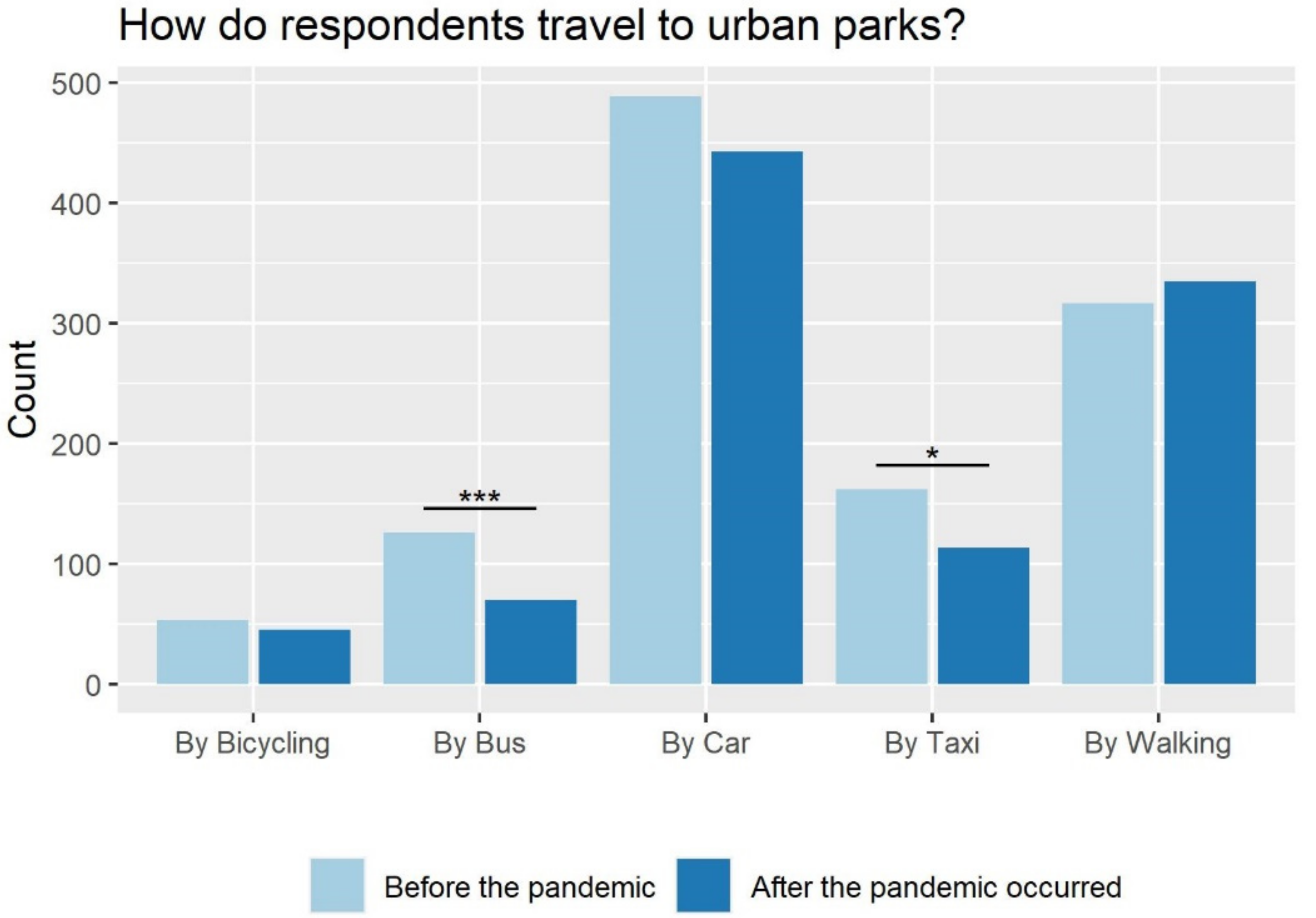

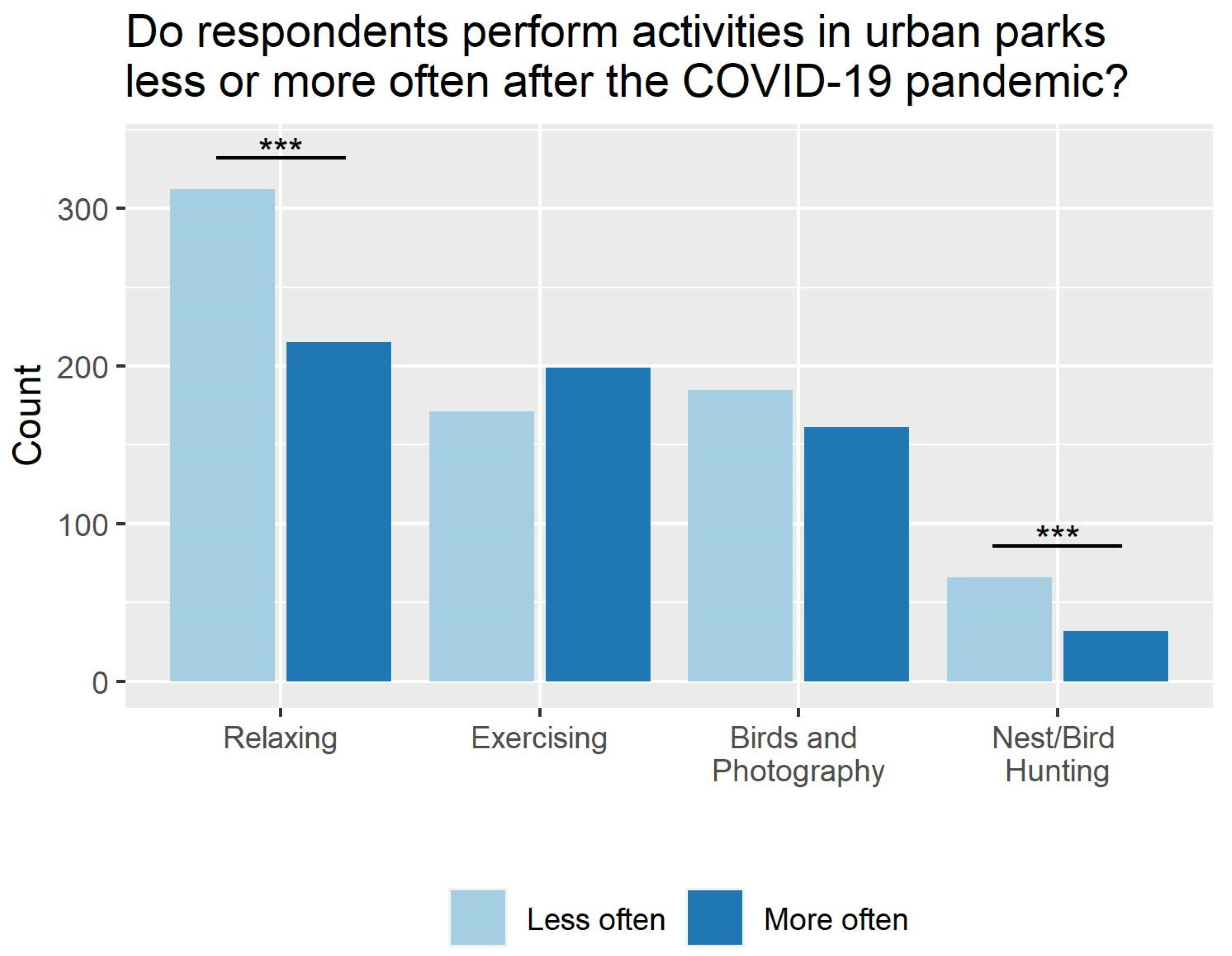

3.2. Urban Parks (Public Green Spaces)

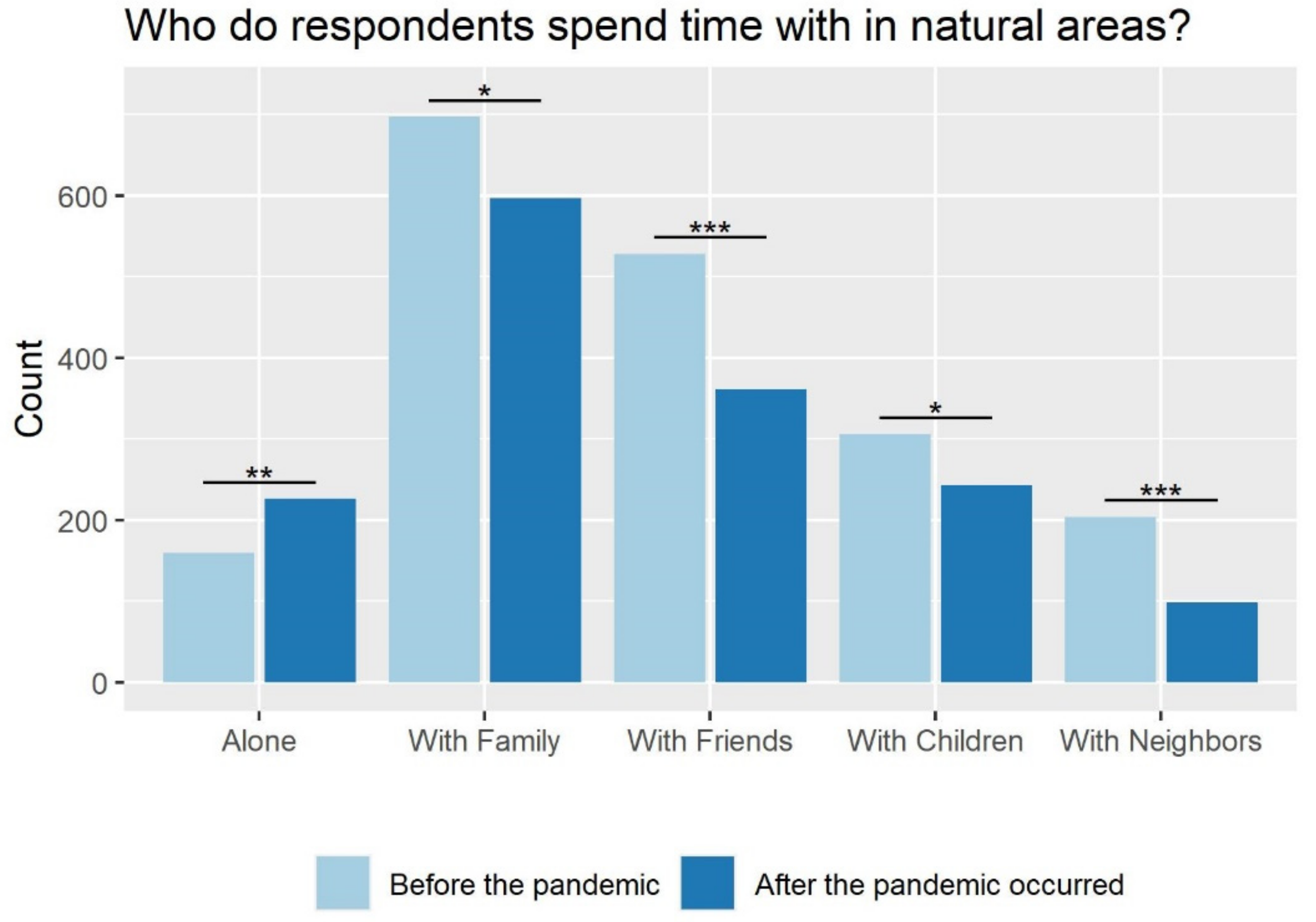

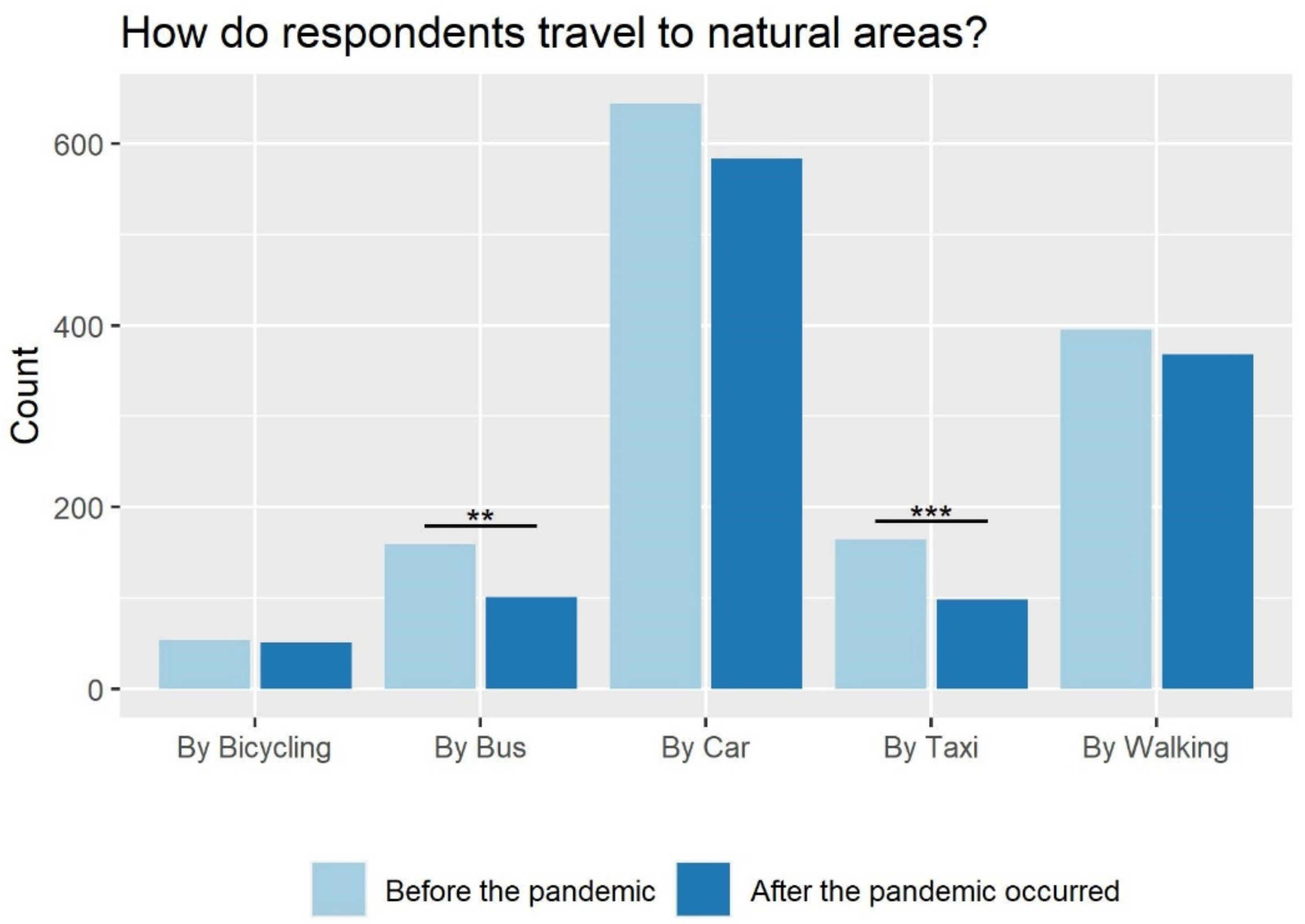

3.3. Natural Areas

4. Discussion

4.1. Impacts of Lockdown on Visitation

4.2. Changes in Activities following the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Home Garden | Urban Park | Natural Area | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive Appreciation of Nature | Exercising |  |  |  |

| Relaxing, picnicking, socializing |  |  |  | |

| Watching wildlife, birding, and photography |  |  |  | |

| Viewing scenery |  | |||

| Historic and natural site exploration |  | |||

| Walking to green spaces |  |  | ||

| Biking to green spaces |  |  | ||

| Interactive (Cultivation) | Tending vegetables |  | ||

| Tending ornamentals |  | |||

| Tending orchard |  |  | ||

| Landscaping |  |  | ||

| Cultivating crops |  | |||

| Tending livestock |  |  | ||

| Extractive | Gathering plants |  | ||

| Nest searching and hunting |  |  |  | |

| Group camping |  | |||

| Taxiing to green spaces |  |  | ||

| Driving to green spaces |  |  | ||

| Bussing to green spaces |  |  | ||

4.3. Did Demographics Influence Changes in Activities?

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samuelsson, K.; Barthel, S.; Colding, J.; Macassa, G.; Giusti, M. Urban nature as a source of resilience during social distancing amidst the coronavirus pandemic. OSF Prepr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.C.; Innes, J.; Wu, W.; Wang, G. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on urban park visitation: A global analysis. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volenec, Z.M.; Abraham, J.O.; Becker, A.D.; Dobson, A.P. Public parks and the pandemic: How park usage has been affected by COVID-19 policies. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, H. COVID-19 lockdown: Animal life, ecosystem and atmospheric environment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 8161–8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Rushing, A.J.; Athearn, N.; Blackford, T.; Brigham, C.; Cohen, L.; Cole-Will, R.; Edgar, T.; Ellwood, E.R.; Fisichelli, N.; Pritz, C.F.; et al. COVID-19 pandemic impacts on conservation research, management, and public engagement in US national parks. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 257, 109038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Kaur, M.; Narwal, G. Other side of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A review. Pharma. Innov. 2020, 9, 366–369. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/01/world/nasa-china- (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Nienhuis, C.P.; Lesser, I.A. The Impact of COVID-19 on Women’s Physical Activity Behavior and Mental Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A.; Ruano, M.A.; Sanchez-Alcalde, L. Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 728, 138813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitra, J.; Rajendran, S.M.; Jeba Mercy, J.; Jeyakanthan, J. Impact of covid-19 lockdown in tamil nadu: Benefits and challenges on environment perspective. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 57, 370–381. [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian. Silence Is Golden for Whales as Lockdown Reduces Ocean Noise; The Guardian: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gordo, O.; Brotons, L.; Herrando, S.; Gargallo, G. Rapid behavioural response of urban birds to COVID-19 lockdown. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2021, 288, 20202513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenceley, A.; McCool, S.; Newsome, D.; Báez, A.; Barborak, J.R.; Blye, C.-J.; Bricker, K.; Cahyadi, H.S.; Corrigan, K.; Halpenny, E.; et al. Tourism in protected and conserved areas amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Parks 2021, 27, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, A.; Panno, A.; Carrus, G.; Carbone, G.A.; Massullo, C.; Imperatori, C. Stay home, stay safe, stay green: The role of gardening activities on mental health during the Covid-19 home confinement. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2010, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCunn, L.J. The importance of nature to city living during the COVID-19 pandemic: Considerations and goals from environmental psychology. Cities Health 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, H. Crisis Gardening: Addressing Barriers to Home Gardening during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents; The Austrailan Food Network: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sofo, A.; Sofo, A. Correction to: Converting Home Spaces into Food Gardens at the Time of Covid-19 Quarantine: All the Benefits of Plants in this Difficult and Unprecedented Period (Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 2, 131–139, doi: 10.1007/s10745-020-00147-3). Hum. Ecol. 2020, 48, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnett, N.; Qasim, M. Perceived Benefits to Human Well-being of Urban Gardens. HortTechnology 2000, 10, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kellett, J.E. The private garden in England and Wales. Landsc. Plan. 1982, 9, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, L.; Charlebois, S.; Finch, E.; Music, J. Home Food Gardening in Canada in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, J.; Okely, J.A.; Taylor, A.M.; Page, D.; Welstead, M.; Skarabela, B.; Redmond, P.; Cox, S.R.; Russ, T.C. Home garden use during COVID-19: Associations with physical and mental wellbeing in older adults. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 73, 101545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, A.; Bhattacharya, M.; Nigon-Crowley, A.; Kirkpatrick, K.; Katoch, C. Community gardening during times of crisis: Recommendations for community-engaged dialogue, research, and praxis. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2020, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Returning to ’The Good Life’? Chickens and Chicken-keeping during Covid-19 in Britain. Anim. Stud. J. 2021, 10, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, S.; Ferrante, A.; Cocetta, G.; Bulgari, R.; Nicoletto, C.; Sambo, P.; Ertani, A. Food Supply and Urban Gar-dening in the Time of Covid-19. Bull. UASVM Hortic. 2020, 77, 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, S.B.; Narango, D.L.; Avolio, M.L.; Bratt, A.R.; Engebretson, J.M.; Groffman, P.M.; Hall, S.J.; Heffernan, J.B.; Hobbie, S.E.; Larson, K.L.; et al. Residential yard management and landscape cover affect urban bird community diversity across the continental USA. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e02455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, P.L.; Fontaine, J.B.; Hobbs, R.J.; Johnson, T.; Boyle, R.; Lueders, A.S. Do novel ecosystems provide habitat value for wildlife? Revisiting the physiognomy vs. floristics debate. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Helden, B.E.; Close, P.G.; Stewart, B.A.; Speldewinde, P.C.; Comer, S.J. An underrated habitat: Residential gardens support similar mammal assemblages to urban remnant vegetation. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 250, 108760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E.A.; Souza EN, F.; Bleakley LA, D.; Burley, C.; Mott, J.L.; Rue-Glutting, G.; Fellowes, M.D.E. Influ-ence of urbanisation and garden plants on the diversity and abundance of aphids and their ladybird and hoverfly predators. Eur. J. Entomol. 2018, 115, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Majewska, A.A.; Altizer, S. Planting gardens to support insect pollinators. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinschroth, F.; Kowarik, I. COVID -19 crisis demonstrates the urgent need for urban greenspaces. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 18, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H.; Nowell, M. Urban nature in a time of crisis: Recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, W.L.; Pan, B. Understanding changes in park visitation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A spatial application of big data. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, J.; Giessen, L.; Winkel, G. COVID-19-induced visitor boom reveals the importance of forests as critical infrastructure. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Z.D.; Freimund, W.; Dalenberg, D.; Vega, M. Observing COVID-19 related behaviors in a high visitor use area of Arches National Park. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, H.; Olsen, J.R.; Nicholls, N.; Mitchell, R. Change in time spent visiting and experiences of green space following restrictions on movement during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationally representative cross-sectional study of UK adults. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, N.; Corcoran, W.; Hill-James, C.; Langton, B.; Sommer, H.; Fisher, B. The importance of urban natural areas and urban ecosystem services during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.W.; Gladkikh, T.M.; Hackenburg, D.M.; Gould, R.K. COVID-19 and human-nature relationships: Vermonters’ activities in nature and associated nonmaterial values during the pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Luo, S.; Furuya, K.; Sun, D. Urban Parks as Green Buffers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.D.; Farmer, J.R.; Dickinson, S.L.; Robeson, S.M.; Fischer, B.C.; Reynolds, H.L. Climate change impacts and urban green space adaptation efforts: Evidence from U.S. municipal parks and recreation departments. Urban Clim. 2021, 39, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas WDe Hassink, J.; Stuiver, M. The Role of Urban Green Space in Promoting Inclusion: Experiences from the Netherlands. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockenhull, J.; Squibb, K.; Cameron, A. How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected the Way We Access and Interact with the Countryside and the Animals within It? Animals 2021, 11, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupfer, J.A.; Li, Z.; Ning, H.; Huang, X. Using Mobile Device Data to Track the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Spatiotemporal Patterns of National Park Visitation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.N.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Correia, R.A.; Normande, I.C.; Costa, H.C.D.M.; Guedes-Santos, J.; Malhado, A.C.; Carvalho, A.R.; Ladle, R.J. No visit, no interest: How COVID-19 has affected public interest in world’s national parks. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 256, 109015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.A. Camping, glamping, and coronavirus in the United States. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PCBS. The Official Website of the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics—State of Palestine. 2021. Available online: https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_Rainbow/Documents/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AD%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B8%D8%A7%D8%AA%20%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%8A%2097-2010.html (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- PCBS. Municipalities Infrastructure Database of the West Bank and Gaza Strip; Palestinian Bureau of Statistics Publications: Ramallah, Palestine, 2017; Reference No. 4.3.6. Grant No.: CPS 1022 01Y. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, J.; AKhair, A.; Hilal, J.; Ghattas, R.; Hardee, P. Status of the Environment in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, A Human Rights-Based Approach; The Applied Research Institute Jerusalem (ARIJ): Bethlehem, Palestine, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qumsiyeh, M.; Amro, Z. Nature Protection and Environmental Reserves in Palestine: Opportunities and Challenges. In The Seventh Palestinian Environmental Awareness and Education Conference Proceedings; The Environmental Education Center: Bethlehem, Palestine, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nekolný, L.; Fialová, D. Attendance and Perceived Constraints to Attendance at Zoological Gardens during the Spring 2020 COVID-19 Re-Opening: The Czechia Case. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2021, 2, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C.E.; Bergstrom, J.; Salazar, J.; Turner, D. How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Outdoor Recreation in the U.S.? A Revealed Preference Approach. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NapoleonCat. Official Website of NapoleonCat Social Media Analytics Platform. 2021. Available online: https://napoleoncat.com/stats/facebook-users-in-state_of_palestine/2021/01/ (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Boone, H.N.; Boone, D.A. Analyzing likert data. J. Ext. 2012, 50, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino, A.R., Jr. Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. J. Grad. Med Educ. 2013, 5, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.H. Handbook of Biological Statistics, 3rd ed.; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2021. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Dyson, K.; Dawwas, E. Nature and Covid-19 (Version 1.0). 2021. Available online: https://github.com/kdyson/nature_covid19 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Christie, M.E. Kitchenspace, Fiestas, and Cultural Reproduction in Mexican House-Lot Gardens. Geogr. Rev. 2004, 94, 368–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WinklerPrins, A.M. House-Lot Gardens in Santarém, Pará, Brazil: Linking the Urban with the Rural. Urban Ecosyst. 2002, 6, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemperman, A.; Timmermans, H. Green spaces in the direct living environment and social contacts of the aging population. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 129, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahriny, F.; Bell, S. Patterns of Urban Park Use and Their Relationship to Factors of Quality: A Case Study of Tehran, Iran. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainability of cities. Adv. Archit. Ser. 2004, 18, 335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak, A. The contribution of local parks to neighbourhood social ties. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwari, N.; Ahmed, M.T.; Islam, M.R.; Hadiuzzaman, M.; Amin, S. Exploring the travel behavior changes caused by the COVID-19 crisis: A case study for a developing country. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, E.; Manoj, B.; Wadud, Z.; Goswami, A.K.; Choudhury, C.F. Modelling the effects of COVID-19 on travel mode choice behaviour in India. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Calaza-Martínez, P.; Cariñanos, P.; Dobbs, C.; Ostoić, S.K.; Marin, A.M.; Pearlmutter, D.; Saaroni, H.; Šaulienė, I.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: An international exploratory study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Yamaura, Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, D.N.; Monz, C.A. Trampling disturbance of high-elevation vegetation, Wind River Mountains, Wyoming, USA. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2002, 34, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.N. Impacts of hiking and camping on soils and vegetation: A review. Environ. Impacts Ecotourism 2004, 41, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, M.; Dandy, N. Recreationist behaviour in forests and the disturbance of wildlife. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 2967–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PCBS. The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics and the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities Issue a Press Release on the Occasion of World Tourism Day. The Official Website of the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics—State of Palestine. 2020. Available online: https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/postar.aspx?lang=ar&ItemID=3816 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Lindsey, P.; Allan, J.; Brehony, P.; Dickman, A.; Robson, A.; Begg, C.; Bhammar, H.; Blanken, L.; Breuer, T.; Fitzgerald, K.; et al. Conserving Africa’s wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekwilder, J. The Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on the Safari Industry (November Update). 11 November 2021. Available online: https://www.safaribookings.com/blog/coronavirus-outbreak (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- El Shaer, H.; Omer, K.; Albaradeiya, I.; Mahassneh, M.; Subah, I.; Dardounah, A.; Abu-Dayeh, K.; Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Jamous, R.; Al-Basha, W.; et al. State of Palestine Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity; EQA: Ramallah, Palestine , 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, P. Palestine Mountain Gazelle Now Endangered, Say Scientists. The Guardian. 2015. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/04/palestine-mountain-gazelle-now-endangered-say-scientists (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Hashem, B. The Rapid Degradation of Wadi Gaza. EcoMENA Echoing Ststainability in MENA Website. 2021. Available online: https://www.ecomena.org/wadi-gaza/ (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Ballas, M. Warning of the Dangers of “Poaching” on Biodiversity in Palestine. Al-Ayam Newspaper Website. 2021. Available online: https://www.al-ayyam.ps/ar_page.php?id=146788e0y342329568Y146788e0 (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- BBC. Rhino Poaching in South Africa Falls during Covid-19 Lockdown. BBC Website. 2021. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55889766 (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Koju, N.P.; Kandel, R.C.; Acharya, H.B.; Dhakal, B.K.; Bhuju, D.R. COVID-19 lockdown frees wildlife to roam but increases poaching threats in Nepal. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 9198–9205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Access and Use of Green Areas during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Green Infrastructure Management in the “New Normal”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenichyn, K. Women and physical activity in an urban park: Enrichment and support through an ethic of care. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shores, K.A.; West, S.T. Rural and urban park visits and park-based physical activity. Prev. Med. 2010, 50, S13–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.L.; Shinew, K.J. The role of gender, race, and income on park use constraints. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 1998, 16, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic | Variable | Responses | % Sample | % West Bank (Study Pop’n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 591 | 46.4 | 50.8 | ||

| Female | 683 | 53.6 | 49.2 | |||

| Marital status | Single | 436 | 34.2 | 35.3 | ||

| Married | 814 | 63.9 | 60.8 | |||

| Other | 24 | 1.9 | 4.9 | |||

| Age group | 18–25 | 344 | 26.9 | 32.1 | ||

| 26–35 | 358 | 28.0 | 25.7 | |||

| 36–45 | 258 | 20.2 | 16.9 | |||

| 46–55 | 198 | 15.5 | 11.8 | |||

| 56–65 | 101 | 7.8 | 7.4 | |||

| Over 65 | 19 | 1.5 | 6.2 | |||

| Housing type | Apartment | 456 | 35.7 | 40.0 | ||

| House | 820 | 64.3 | 60.0 | |||

| Place of living | Urban | City | 636 | 49.9 | 70.4 | 71.0 |

| Town | 262 | 20.5 | ||||

| Rural | Village | 333 | 26.1 | 24.0 | ||

| Refugee camp | 44 | 3.5 | 5.0 | |||

| Distribution bygovernorate | Jerusalem | 126 | 10.0 | 15.1 | ||

| Jenin | 111 | 8.8 | 10.9 | |||

| Tubas | 53 | 4.2 | 2.1 | |||

| Tulkarem | 112 | 8.9 | 6.4 | |||

| Nablus | 197 | 15.6 | 13.3 | |||

| Qalqelyah | 68 | 5.4 | 3.9 | |||

| Salfit | 61 | 4.8 | 2.6 | |||

| Ramallah | 154 | 12.0 | 11.4 | |||

| Jericho | 9 | 0.7 | 1.7 | |||

| Bethlehem | 102 | 8.1 | 7.5 | |||

| Hebron | 272 | 21.6 | 25.1 | |||

| Employment For comparison, 214 students were excluded from the calculations | Employed | 795 | 76.1 | 74.0 | ||

| Unemployed | 238 | 23.9 | 26.0 | |||

| Work location | Inside the West Bank | 927 | 90.0 | 86.9 | ||

| Inside the Greenline | 103 | 10.0 | 13.1 | |||

| Education | High School or Less | 187 | 14.7 | --- | ||

| Bachelor | 755 | 59.5 | --- | |||

| Diploma | 115 | 9.1 | --- | |||

| Masters or more | 212 | 16.7 | --- | |||

| Income before COVID-19 | Less than 2000 NIS | 136 | 11.8 | 14.0 | ||

| 2001–4000 NIS | 375 | 32.4 | --- | |||

| 4001–6000 NIS | 196 | 17.0 | --- | |||

| 6001–8000 NIS | 64 | 5.5 | --- | |||

| More than 8000 NIS | 59 | 5.1 | --- | |||

| I have no income | 326 | 28.2 | --- | |||

| I prefer not to answer | 104 | Excluded for comparison | --- | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dawwas, E.B.; Dyson, K. COVID-19 Changed Human-Nature Interactions across Green Space Types: Evidence of Change in Multiple Types of Activities from the West Bank, Palestine. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413831

Dawwas EB, Dyson K. COVID-19 Changed Human-Nature Interactions across Green Space Types: Evidence of Change in Multiple Types of Activities from the West Bank, Palestine. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413831

Chicago/Turabian StyleDawwas, Emad B., and Karen Dyson. 2021. "COVID-19 Changed Human-Nature Interactions across Green Space Types: Evidence of Change in Multiple Types of Activities from the West Bank, Palestine" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413831

APA StyleDawwas, E. B., & Dyson, K. (2021). COVID-19 Changed Human-Nature Interactions across Green Space Types: Evidence of Change in Multiple Types of Activities from the West Bank, Palestine. Sustainability, 13(24), 13831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413831