Abstract

Building on sustainable supply chain management and operations strategy literature, our study seeks to identify structural relationships between switching cost and sustainable supplier relationships from a demand-side perspective. More specifically, this study looks at the impact of the switching cost on process monitoring, operation integration, and sustainable supplier relationships. To test the structural relationships in our research model, we used Manufacturing Productivity Survey data from Korea to conduct an empirical analysis based on 351 data that fit our study’s purpose. The results show that the indirect effect of switching cost on sustainable supplier relationships through process monitoring and operational integration is positively valid. Additionally, the results emphasize that the social exchange theory can be explained in the perspective of the switching cost.

1. Introduction

A sustainable supplier relationship has been a concern for firms seeking long-term and secure supply chain relationships. Ren et al. [1] found that supply chain players should have or expect a long-term relationship that would provide unique resources, not parallel with short-term relationships. For example, close and favorable supplier relationships in the long-term period have been sought extensively in Japan, and the concept and lessons were spread widely [2].

Social exchange theory serves as a fundamental mechanism in the study of building and maintaining relationships [3,4]. According to Homans [5], who first developed the social exchange theory, all humans change their behavior after comparing subjective costs and benefits. When judging aspects to benefit each other in cross-organizational transactions, sustainable relationships are possible. That is the fundamental proposition of social exchange theory. Therefore, the existence of a transaction relationship depends on mutual compensation levels of investment efforts.

Because most sustainable relationships are within operational sustainability, interpretations based on supply chain contexts become more important [6]. A long-term supplier relationship implies no change or switching for suppliers during a considerable period because barriers to entry hinder another supplier from the pool of suppliers. We call the barrier to entry for suppliers the switching cost of buyers. However, switching cost does not bring about a sustainable supplier relationship without fail; instead it is just one of several aspects. Accordingly, many researchers have begun to pay more attention to this subject, which might play a significant role between switching costs and sustainable supplier relationships. The findings of Helper et al. [7] show that upgrading contracted organizations themselves through mutual orchestration and collaboration while monitoring each other’s performance is achieved through learning by monitoring. This can be understood by the fact that the higher a switching cost (maintaining current supply contracts) is spent, the higher monitoring the effort required. Further, the governance characteristics, such as monitoring, affects integration across organizations [8]. In this context, monitoring is not surveillance, rather a chance to get to know each other with diverse interactions such as information sharing. Simatupang and Sridharan [9] indicate that the integration of supply chain processes generates long-term relationships with suppliers and provides a variety of data that could be used, while showing supply chain visibility and risk-sharing.

2. Background and Motivation

In the above context, we raise the following question: “How does switching cost affect sustainable supplier relationships in direct and indirect ways?” The answer to this question explains the gap in the existing literature. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no attempt to (a) use both the process monitoring and operational integration for mediators to explain the relationship between switching cost and sustainable supplier relationships, or (b) adopt the concept of switching cost, which has been used in the marketing area. The results are believed to contribute to the literature by shedding light on the a less-explored area of switching cost.

Despite the above findings, the indirect effect of switching costs on sustainable supplier relationships is not fully explained. Thus, we proposed monitoring and operational integration as mediators in our research model. We tried to uncover how switching cost affects sustainable supplier relationships through the double-mediating effects of process monitoring and operational integration.

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses

The concept of switching costs has been widely used in relationship marketing literature to increase customer retention in business-to-customer (B2C) markets [10]. In general, switching cost is one of the principal sources to help a buying company lock in a long relationship with a supplier. In other words, switching costs represent additional costs, efforts, etc., that arise when a new supplier is selected instead of the relationship with the current supplier. Switching costs do not result in a one-off transaction between suppliers and buyers. This phenomenon is called the lock-in effect. A case in point is that customers who used certain smartphones continue to use the same company’s products, or that companies that receive certain facilities or parts do not change their suppliers [11].

On the contrary, buying companies often replace the supply bases for their own benefit. In addition, buying companies may have a variety of suppliers and choose according to their strategic criteria. However, it is not an easy decision. Sukky [12] demonstrated the need for a dynamic decision-making principle, arguing that the selection of suppliers should consider the time-based interdependence of the investment in selecting new suppliers and the costs of transitioning from existing suppliers to new suppliers.

When switching costs are divided into three categories: procedural, financial, and relationship, the transition costs associated with the relationship are most strongly associated with the consumer’s intention to repurchase, and the transition costs associated with the process and relationship mitigate the association between the buyer’s satisfaction and the intention to repurchase, while the financial transition costs strengthen them [13]. This implies that the relationship between suppliers and purchasing firms is of considerable importance and that there is a need to act strategically and operationally toward the same goal.

Just as Blut et al. [14] revealed the impact of switching costs on consumer loyalty depending on the type of service, it is necessary to reveal that the industry’s nature, and suppliers’ type of products may affect the repurchase of the purchaser. Li et al. [15] said that when a buyer switches suppliers concerning switching costs, it considers new strategies of suppliers that want to replace existing suppliers. However, it shows that in this case, the buyer may need to demand higher standards from the new supplier or provide a better level of products and services. Therefore, it was argued that the new supplier should develop a different level of capability than the existing supplier and provide other forms of results that provide a higher level of value. Although Blut et al. [10] demonstrated that the impact of switching costs on behavioral performance between suppliers and purchasing firms in transactions between them is unclear, it could be inferred that switching cost has an effect on sustainable supplier relationships. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Switching cost positively affects sustainable supplier relationships.

In the perspective of transaction cost theory, opportunism gives rise to transaction costs [16]. Ketchen and Hult [17] emphasized that short-term transaction costs are of the most significant concern within the traditional supply chain, creating opportunism. Therefore, it was argued that trust between suppliers and buyers is critical. Decisions should be made in terms of total costs in the supply chain, not in terms of short-term transaction costs, for desirable long-term transactions. Watne and Heide [18] described the conditions under which opportunism occurred in existing or emerging transaction relationships and described new structures and concepts for opportunism.

Further, Klemperer [19] considered transaction cost as one of the switching costs. Kashyap et al. [20] insisted that an unbalanced contractual relationship induced a higher level of monitoring, related to less opportunism. This means that monitoring is presented as a way to reduce this opportunism. In this regard, we expect that higher switching cost makes it hard to replace existing suppliers with new ones, which leads buyers to check and monitor more frequently for persistent quality. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Switching cost positively affects process monitoring.

In the current business environment, which leads from competition among companies to competition between supply chains, supply chains’ capabilities are essential for the survival of companies. Ironically, however, the internal financial and administrative resources needed to execute the supply chain’s capability are becoming increasingly scarce [21]. Therefore, companies need to integrate with other companies in the supply chain because it is challenging to internalize all different supply chain capabilities. Flynn et al. [22] applied a prior definition of integration to the supplier chain situation, defining supplier chain integration as how the manufacturer wants to cooperate with its suppliers strategically and manage processes within and across the organization in cooperation. Further, Flynn et al. [22], who applied the contingency theory in the study between the integration of supply chains and corporate performance, argued that the environment in which the organization operates creates organizational structures and processes, and that in order to improve performance, organizations need to align organizational structures and processes with the environment facing the organization [23,24]. In particular, customers and suppliers are essential members of the manufacturing enterprise’s environment [22], which can be interpreted in the context of the above integrations. Swink et al. [25] identified the total effect of consolidation through which the effect of integration is significantly linked to management performance, as integration by type of supply chain can directly impact management performance and indirectly impact on management performance while enhancing the competitive capabilities of the entity. Zhao et al. [26] showed that in order for supply chain integration to occur, organizational internal integration and commitment to supplier–buyer enterprise relationships must precede. In particular, internal integration has a more significant impact on supply chain integration. Mukhopadhyay and Kekre [27] also saw other forms of benefits in integrating the supply chain, separating strategic and operational gains. Researchers demonstrated that if strategic gains were focused on enhancing the organization’s capabilities, they would improve processes. Although there has been much research on supplier integration in the dimensions of supply chain integration, the study of operational integration with suppliers is hard to find in existing studies. In this study, we examine supply chain integration as operational integration from a more detailed perspective. Switching costs would increase when supply chain members make a specific investment for mutual interests [28,29]. Thus, switching costs originating from transaction-specific investments lead to operational integration on the supply chains. Jayaram et al. [30] found that the firm’s effective IT monitoring improves the process integration significantly. Richey et al. [31] argued that external monitoring failure brings about business process barriers to supply chain integration. In this regard, the integration does not occur without appropriate monitoring. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Switching cost positively affects operational integration.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Process monitoring positively affects operational integration.

Finding the right supplier to have a sustainable long-term relationship with is a strategic issue [32]. Leppelt et al. [6] showed that sustainability leaders (SLs: companies listed in both DJSI and FTSE4Good Index) invent sustainable supplier relationship management practices, unlike sustainability followers (SFs: companies not listed in both DJSI and FTSE4Good Index or which made the listing in only one of the two indices), which makes SLs cope with ecologic and social sustainability better than SFs. The sustainable supplier relationship requires the trust between buyer and supplier through relational stability without any reneging [33]. In this context, operational integration, which can be called internal integration, has positive effect on sustainable supplier relationship.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Operational integration positively affects sustainable supplier relationships.

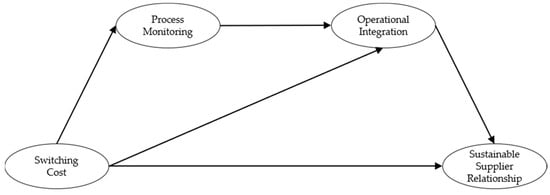

Based on the theoretical background examined, a research model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Data

We used the MPS (Manufacturing Productivity Survey) data collected by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, and the KPC (Korea Productivity Center), by jointly conducting a corporate survey to develop statistics on companies’ site productivity. MPS data were collected from each of the seven departments (financial management, personnel management, planning management, sales planning, operations management, procurement management, research, and development) in the individual firm. In other words, MPS data have been available to multifunctional, multirespondent individuals in each individual firm, thereby mitigating any CMB (common method bias) problems arising from the same respondent. An earlier study [34] already used MPS data to study topics unrelated to this study.

The target population for this study is a manufacturing firm and a first-tier supplier. They have suppliers with continuous business relationships. We used 351 firm-level data to test the research model presented in this study. Table 1 shows sample firms’ characteristics in terms of industries, holding status, firm age, sales revenue, and supply chain position.

Table 1.

Characteristics of sample firms.

4.2. Measurement

The constructs included in our research model were measured by multi-items. The measurement items have been appropriately adapted to the purpose of this study, based on existing research. A seven-point Likert Scale was used (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Specific survey questions are attached in Appendix A. The switching cost was measured using two questions (time and cost required to change to a new supplier). Some constructs (processes, monitoring and operational integration) were measured in four items. Lastly, sustainable supplier relationships are measured in two items, with specific questions being: (1) Both parties recognize that they are partners and cooperating. (2) The contract is written and operated relatively in respect of mutual benefit.

4.3. Reliability

The reliability of each construct of measurement items was tested with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were all above the standard criteria of 0.7 (see Table 2). Therefore, there was no problem with internal consistency.

Table 2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA).

4.4. Validity

We assessed the construct validity of our measures following Anderson and Gerbing’s two-step approach [35]. Following Anderson and Gerbing’s two-step approach, we employed structural equation modeling (SEM) using Lisrel 8.8 to test the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) for the measurement model before testing the research model. The fit index of the measurement is , , /, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.955, Tucker–Lewis Fit Index (TLI) = 0.938, Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.078, Standardized Root-Mean-Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.046. The general criteria are not more than 3.0 for /, not less than 0.9 for CFI and TLI, and not more than 0.08 and 0.05 for RMSEA and SRMR, respectively. / is slightly below the general standard, but the remaining fit indices meet the general criteria. Therefore, the fit index of the measurement is acceptable. Table 2 shows the results of the CFA. Through the CFA, we tried to secure the convergent and discriminant validity. In Table 2, the coefficient for each construct of measurement items was significant at the significant level of 0.01, and the value of Composite Reliability (C.R.) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) exceeded the general criteria. The Criteria for C. R. and AVE are 0.7 and 0.5, respectively [36]. So, convergent validity was not an issue in the measurement model of this study.

Table 3 shows the results of the discriminant validity between the constructs used in the research model. According to Fornell and Larker [36], discriminant validity was tested by examining whether AVE’s positive square-root value was greater than the correlation coefficient value. Table 3 shows that the diagonal value is greater than the nondiagonal value. Therefore, we concluded that the discriminant validity of our research model is not problematic.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

5. Results

We employed SEM using Lisrel 8.8 to test the research model. Above all, our research model is expressed in mathematical expressions as follows:

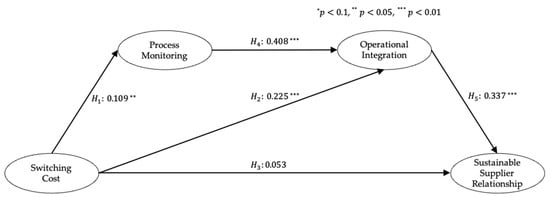

Table 4 shows that the fit of the study model is not problematic. Figure 2 indicates the hypothesis test results of our research model. Hypothesis 1 is intended to examine the positive influence of switching costs on process monitoring. The switching cost had a positive impact on process monitoring at a significance level of 0.05. Hypothesis 1 was, therefore, accepted. Hypothesis 2 is the relationship between switching cost and operational integration. The switching cost had a statistically positive impact on operational integration (γ_21 = 0.225, t-value = 3.301). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was also adopted. Switching suppliers is not a minor decision to make [33]. Although buyers have recognized that switching costs are high, it can be judged as a good sign that monitoring and operational integration practices for long-term supplier relationships positively correlate with switching costs. The switching cost had no direct impact on sustainable supplier relationships, so Hypothesis 3 was rejected. Contrary to the expected results, we confirmed that buyers’ perception of switching costs could not directly lead to sustainable long-term relationships with suppliers. Hypothesis 4 is the relationship between process monitoring and operational integration. Process monitoring had a positive impact on operational integration at a significance level of 0.01. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was adopted. Finally, Hypothesis 5 was also adopted. The sustainable supplier relationship was positively influenced by operational integration (β_32 = 0.337, t-value = 5.178). Even if the supplier’s switching cost is high, we statistically confirmed that process monitoring and operational integration practices should maintain a sustainable relationship.

Table 4.

Fit index of the research model.

Figure 2.

Hypothesis test results of the research model.

Table 5 shows drivers of SSCM adoption suggested in previous studies [37]. Unlike previous studies, we considered switching cost, process monitoring, and operational integration as drivers of the sustainable supplier relationship, and this is also a differentiated point of earlier studies.

Table 5.

Drivers of SSCM adoption.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Building on sustainable supply chain management and operations strategy literature, our study seeks to identify structural relationships between switching cost and sustainable supplier relationships from a demand-side perspective. More specifically, this study looks at the impact of the switching cost on process monitoring, operation integration, and sustainable supplier relationships. We also look at the structural relationship between process monitoring and operational integration and operational integration and sustainable supplier relationships. To test the structural relationships in our research model, we used MPS data to conduct an empirical analysis based on 351 data that fit our study’s purpose.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

Our study offers contributions to academic implications. To understand the gap between the existing literature and our study, we tried to find the relevant literature. Table 6 contains the academic contributions of previous literature in perspective of four pillars, which comprise main constructs of this study. This approach is in line with previous studies [55,56,57].

Table 6.

Contributions of previous authors.

First, the switching costs have been mainly utilized in B2C transactions in the marketing field. We applied it to B2B transactions in the SCM field to shed new light on the new role of switching costs. Switching suppliers is not minor decision-making [33]. Nevertheless, a buyer’s perception of switching costs cannot directly lead to sustainable long-term relationships with the suppliers. Recently, the literature on buyer–supplier relationships has been more interested in psychological contracts, i.e., relationships at a cognitive level [33,63]. When the buyer believes that the supplier is not clearly performing what needs to be done, the buyer psychologically begins to consider whether the relationship should continue or not. Psychological worry in supplier relationships prevents them from leading to sustainable long-term relationships. Therefore, both supplier’s process monitoring and operational integration practices are required to maintain sustainable relationships. Second, as mentioned, we consider process monitoring and operational integration as mediating variables to provide a more structured understanding of switching costs and sustainable supplier relationships. In our research model, process monitoring is a mediating role in the relationship between switching cost and operational integration. The indirect effects of process monitoring enhance operational integration. Operational integration has a positive impact on sustainable supplier relationships. When the switching cost is recognized, buyers need to lead into long-term sustainable relationships through process monitoring and operational integration activities. The previous results emphasize that the social exchange theory can be explained in the perspective of the switching cost. When judging aspects to benefit each other in cross-organizational transactions, sustainable relationships are possible [5]. That is the fundamental proposition of social exchange theory. Therefore, a sustainable relationship depends on how much compensation investment efforts are linked. These efforts are considered as process monitoring and operational integration in this study.

6.2. Managerial Implications

Our demonstration highlights the importance of switching costs, which, however, does not affect the sustainable supplier relationship without relationship management capabilities such as process monitoring and operational integration. In this regard, results show that supply chain managers should manage their relationship management capabilities with considering intentions to switch suppliers. More specifically, the buyer needs to continuously check whether the supplier faithfully implements the contract, whether they use related information and technologies for other purposes, or whether they have superior capabilities compared to other suppliers. In addition, buyers should share market and customer-related information, inventory information, and production plans for a high level of operational integration with suppliers. The collaboration of Apple and LG Display can be the case of the above implication. LG Display has supplied diverse display components including OLED panels while enhancing its R&D capability. Because independence from LG Display would burden Apple with a high risk for sourcing, Apple would not switch the display supplier to another firm, which induces the sustainable supply relationship [64].

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study contributes to theory and practice, it has some limitations. However, this will be the cornerstone for further research. First, the sample of this study is a Korean manufacturer. Considering that the study results on sustainable social relations are dependent on the cultural context of Korea [65,66], our findings may not be able to generalize beyond the Korean sample. Therefore, it would be very interesting to collect additional data from manufacturing companies in other countries in the future and compare them with the results of this study. Second, it is necessary to consider industrial and corporate characteristics as control variables to increase the study’s internal validity. Third, in addition to securing internal and external validity, moderating variables need to be considered. The moderators will be more helpful in understanding the structural relationships discussed in this study. Finally, it is necessary to find out whether the psychological contract violation felt by the supplier was caused by the unfair treatment of the buyer [33,63].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.; methodology, J.P.; software, J.P.; validation, S.L. and J.P.; formal analysis, J.P.; investigation, S.L. and J.P.; data curation, J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. and J.P.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and J.P.; supervision, S.L. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the university innovation support project of Hoseo University, grant number 221-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to the privacy of data sources.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the highly valuable comments and suggestions provided by the editors and reviewers, which contributed to the improvement in the clarity, contribution, and scientific soundness of the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Survey items

Switching Cost

(1) It takes much time to change to a new supplier.

(2) It takes a lot of money to change to a new supplier.

Process Monitoring

(1) It is continuously checked whether the contract is being faithfully implemented.

(2) It is continuously checked whether information/task/technology is not used for other purposes.

(3) It is continuously checked whether our suppliers are superior in capability compared to other suppliers.

(4) It is continuously checked whether there is a standard for continuous development of business relationships.

Operational Integration

(1) Both parties share market- and customer-related information.

(2) Both parties share inventory information.

(3) Both parties share production plans.

(4) Both parties synchronize production schedules.

Sustainable Supplier Relationship

(1) Both parties recognize that they are partners and are cooperating.

(2) The contract is written and operated relatively in respect of mutual benefit.

References

- Ren, Z.J.; Cohen, M.A.; Ho, T.H.; Terwiesch, C. Information Sharing in a Long-Term Supply Chain Relationship: The Role of Customer Review Strategy. Oper. Res. 2010, 58, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mcmillan, J. Managing Suppliers: Incentive Systems in Japanese and US Industry. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1990, 32, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Narus, J. A Model of Distribution Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, F.S.; Gassenheimer, J.B. Marketing and Exchange. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior as Exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppelt, T.; Foerstl, K.; Reuter, C.; Hartmann, E. Sustainability Management beyond Organizational Boundaries-Sustainable Supplier Relationship Management in the Chemical Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helper, S.; Macduffie, J.P.; Sabel, C. Pragmatic Collaborations: Advancing Knowledge While Controlling Opportunism. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2000, 9, 443–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Helfat, C.E.; Campo-Rembado, M.A. Integrative Capabilities, Vertical Integration, and Innovation Over Successive Technology Lifecycles. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simatupang, T.M.; Sridharan, R. Design for Supply Chain Collaboration. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2008, 14, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Evanschitzky, H.; Backhaus, C.; Rudd, J.; Marck, M. Securing Business-to-Business Relationships: The Impact of Switching Costs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 52, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farrell, J.; Klemperer, P. Chapter 31 Coordination and Lock-In: Competition with Switching Costs and Network Effects. Handb. Ind. Organ. 2007, 3, 1967–2072. [Google Scholar]

- Sucky, E. A Model for Dynamic Strategic Vendor Selection. Comput. Oper. Res. 2007, 43, 3638–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Frennea, C.M.; Mittal, V.; Mothersbaugh, D.L. How Procedural, Financial and Relational Switching Costs Affect Customer Satisfaction, Repurchase Intentions, and Repurchase Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2015, 32, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blut, M.; Beatty, S.E.; Evanschitzky, H.; Brock, C. The Impact of Service Characteristics on the Switching Cost-Customer Loyalty Link. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Madhok, A.; Plaschka, G.; Verma, R. Supplier Switching Inertia and Competitive Asymmetry: A Demand Side Perspective. Decis. Sci. 2006, 37, 547–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grover, V.; Malhotra, M.K. Transaction Cost Framework in Operations and Supply Chain Management Research: Theory and Measurement. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 45–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M. Bridging Organization Theory and Supply Chain Management: The Case of Best Value Supply Chains. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathne, K.H.; Heide, J.B. Opportunism in Interfirm Relationships: Forms, Outcomes, and Solutions. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemperer, P. Competition When Consumers Have Switching Costs: An Overview with Applications to Industrial Organization, Macroeconomics, and International Trade. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1995, 62, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kashyap, V.; Antia, K.D.; Frazier, G.L. Contracts, Extracontractual Incentives, and Ex Post Behavior in Franchise Channel Relationships. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W. The Effect of Supply Chain Integration on the Alignment Between Corporate Competitive Capability and Supply Chain Operational Capability. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Man. 2006, 26, 1084–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flynn, B.B.; Huo, B.; Zhao, X. The Impact of Supply Chain Integration on Performance: A Contingency and Configuration Approach. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L. The Contingency Theory of Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, P.R.; Lorsch, J.W. Organization and Environment; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Swink, M.; Narasimhan, R.; Wang, C. Managing beyond the Factory Walls: Effects of Four Types of Strategic Integration on Manufacturing Plant Performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huo, B.; Selen, W.; Yeung, J.H.Y. The Impact of Internal Integration and Relationship Commitment on External Integration. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukopadhyay, T.; Kekre, S. Strategic and Operational Benefits of Electronic Integration in B2B Procurement Processes. Manage. Sci. 2002, 48, 1301–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, M.C.; Huang, H.H. How Transaction-Specific Investments Influence Firm Performance in Buyer-Supplier Relationships: The Mediating Role of Supply Chain Integration. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2019, 24, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, D.; Olhager, J. Supply Chain Integration and Performance: The Effects of Long-Term Relationships, Information Technology and Sharing, and Logistics Integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaram, J.; Tan, K.C.; Nachiappan, S.P. Examining the Interrelationships between Supply Chain Integration Scope and Supply Chain Management Efforts. Int. J. Pro. Res. 2010, 48, 6837–6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, R.G., Jr.; Chen, H.; Upreti, R.; Fawcett, S.E.; Adams, F.G. The Moderating Role of Barriers on the Relationship between Drivers to Supply Chain Integration and Firm Performance. Int. J. Phys. Distr. Log. 2009, 39, 826–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikhani, R.; Torabi, S.A.; Altay, N. Strategic Supplier Selection under Sustainability and Risk Criteria. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 208, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blessley, M.; Mir, S.; Zacharia, Z.; Aloysius, J. Breaching Relational Obligations in a Buyer-Supplier Relationship: Feeling of Violation, Fairness Perceptions and Supplier Switching. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 74, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Schoenherr, T. The Effects of Supply Chain Integration on the Cost Efficiency of Contract Manufacturing. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 54, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modelling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models wth Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.B.; Desai, T.N. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Developments in Sustainable Supply Chain Management. Int. J. Logist.-Res Appl. 2019, 22, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, M.; Govindan, K.; Sarkis, J.; Seuring, S. Quantitative Models for Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Developments and Directions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 233, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S. Supply Chain Management for Sustainable Products – Insights from Research Applying Mixed Methodologies. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2011, 20, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Z.N.; Kant, R. A State-of-Art Literature Review Reflecting 15 Years of Focus on Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2524–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, A.; Leat, M.; Hudson-Smith, M. Making Connections: A Review of Supply Chain Management and Sustainability Literature. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 17, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Wu, Z.H. Building a More Complete Theory of Sustainable Supply Chain Management Using Case Studies of 10 Exemplars. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. A Comparative Literature Analysis of Definitions for Green and Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, M.; Papadopoulos, T. Supply Chain Sustainability: A Risk Management Approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Rajendran, S.; Sarkis, J.; Murugesan, P. Multi Criteria Decision Making Approaches for Green Supplier Evaluation and Selection: A Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 98, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassini, E.; Surti, C.; Searcy, C. A Literature Review and a Case Study of Sustainable Supply Chains with a Focus on Metrics. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, B.; Quazi, A.; Kriz, A.; Coltman, T. In Pursuit of a Sustainable Supply Chain: Insights from Westpac Banking Corporation. Supply Chain Manag. 2008, 13, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Touboulic, A.; Walker, H. Theories in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Structured Literature Review. J. Serv. Manag. 2015, 45, 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, R.U.; Seuring, S.; Beske, P.; Land, A.; Yawar, S.A.; Wagner, R. Putting Sustainable Supply Chain Management into Base of the Pyramid Research. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 20, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S.; Jeyaraman, K.; Vengadasan, G.; Premkumar, R. Sustainable Supply Chain Management (SSCM) in Malaysia: A Survey. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.M.; Knemeyer, A.M.; Gardner, J.T. Supply Chain Partnerships: Model Validation and Implementation. J. Bus. Logist. 2004, 25, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S.K.; Kumar, P.; Barua, M.K. Flexible Decision Approach for Analysing Performance of Sustainable Supply Chains Under Risks/Uncertainty. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2014, 15, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Seuring, S.; Beske, P. Sustainable Supply Chain Management and Inter-Organizational Resources: A Literature Review. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Spalanzani, A. Sustainability of Manufacturing and Services: Investigations for Research and Applications. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.K.; Bhuniya, S.; Sarkar, B. Involvement of Controllable Lead Time and Variable Demand for a Smart Manufacturing System under a Supply Chain Management. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2021, 184, 115464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, H.; Nof, S.Y. Intelligent Information Sharing among Manufacturers in Supply Networks: Supplier Selection Case. J. Intell. Manuf. 2018, 29, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, H.; Nof, S.Y. Collaborative Capacity Sharing among Manufacturers on the Same Supply Network Horizontal Layer For Sustainable and Balanced Returns. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 1622–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guandalini, I.; Sun, W.; Zhou, L. Assessing the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals Through Switching Cost. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 1430–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zheng, X.; Zhuang, G. Information Technology-Enabled Interactions, Mutual Monitoring, and Supplier-Buyer Cooperation: A Network Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 78, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Yang, M.G.M.; Park, Y.; Huo, B. Supply Chain Integration and Its Impact on Sustainability. Ind. Manag. Data. Syst. 2018, 118, 1749–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancha, C.; Longoni, A.; Giménez, C. Sustainable Supplier Development Practices: Drivers and Enablers in a Global Context. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2015, 21, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashi; Cerchione, R.; Centobelli, P.; Shabani, A. Sustainability Orientation, Supply Chain Integration, and Smes Performance: A Causal Analysis. Benchmarking 2018, 25, 3679–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guercini, S.; La Rocca, A.; Runfola, A.; Snehota, I. Interaction Behaviors in Business Relationships and Heuristics: Issues for Management and Research Agenda. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo-Eun, K. LG Getting Closer with Apple. TheKoreaTimes 2021. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/tech/2021/08/133_314046.html (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Putman, R.D. The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life. In The American Prospect; Spring: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; Volume 4, pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Villena, V.H.; Revilla, E.; Choi, T.Y. The Dark Side of Buyer-Supplier Relationships: A Social Capital Perspective. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).