1. Introduction

The term "sustainable management activities" refers to the specific measures that organizations use to achieve superior and sustainable performance [

1]. Examining these activities can pave the way for future competitive advantages [

2,

3,

4] by evaluating and enabling the development of appropriate interventions and actions [

5,

6]. Sustainable management practices benefit multiple stakeholders [

2], serve as a critical resource that helps a business stay ahead of the competition [

3,

7], and eventually increase financial performance [

6,

8]. In other words, they promote competitive advantages that determine a course to be followed, allowing organizations to plan for change and progress toward the future they desire [

7].

The sustainability of business processes in contemporary organizations is gaining prominence and traction in the literature [

9]. This is especially true in information-intensive contexts, where the rise of the service economy has shifted the emphasis to a knowledge-based economy [

10,

11]. Information-intensive processes differ from traditional business processes in terms of complexity, unpredictability, and the degree of collaboration required to achieve a desired service output [

11,

12,

13]. Therefore, organizations should consider these differences when managing these processes [

11,

14]. Business process management (BPM) is used by organizations to analyze and redesign how they manage their current operations in order to improve performance [

15]. Teams and team design are an integral part of business process management, and thereby deserve further attention.

The purpose of this study is to analyze specific sustainable management activities, notably information management and organizational team design, as they are recognized to affect business performance and sustainable competitive advantages [

2,

3]. This research is motivated by several fundamental realities: service industries are an increasingly important factor in modern economies [

16], information intensity has a profound effect on how services are delivered [

17], and team design has a major impact on service delivery performance [

18]. However, studies examining the interaction of these variables are rare. For instance, previous research on team structure and information intensity in service industries has focused on defining the various phenomena [

19], and in cases where empirical work has been conducted, studies are concerned with identifying variables that increase the intensiveness of the service [

20], omitting the impact that team structure can have on overall efficacy. This indicates a gap in the literature that the current work seeks to fill.

The term "information-intensive services" (ISSs) refers to the amount of data and client engagement required to generate a service [

21]. This includes the collation of data from multiple sources and making informed decisions. Our selection of a claims handling service in the motor insurance industry is a typical example. Here, information must be gathered, processed, and distributed to, and from, numerous constituencies, including claimants, service providers (claim investigators, garages, motor engineers, and solicitors), and team members within the claims handling unit. The variability in quality and efficiency is attributed to increased complexity and trends in networking, skills-based routing, and integrated multimedia systems [

22], as well as a lack of homogeneity in the performance indicators [

23].

In this study, we measured performance using two objectively quantifiable measures—the time taken to settle an insurance claim and the total paid per claim. We then examined the impact of information intensity on these indicators. We acknowledge that the design and structure of service teams influence their ability to provide an efficient and cost-effective service; therefore, we compared the results across the two most prevalent team designs, namely the production line approach (PLA) and self-managed work teams (SMWTs). Whereas most previous empirical research has concentrated on either the former [

20] or the latter [

24], the data collected in this study provide a unique chance to compare the two team designs.

We analyzed 24,925 real-life, non-injury motor insurance claims. The claims handling team was organized according to the two major designs (PLA and SMWTs) during two separate and distinct time periods. This enables the investigation of which team structure is best equipped to deal with the information-intensive variables that affect the entire service. Thus, the questions that this research aims to address are:

The contribution of this study, therefore, lies in challenging conventional beliefs around the primacy of self-managed work teams and their impact on sustainable management practices. While we discovered a considerable difference in performance between the two team designs, this difference becomes more apparent when coupled with the fact that information intensity has a direct effect on time and cost, and that this effect is not uniform across both team forms. As a result, this study has major implications for team design in information-intensive activities and sustainable management practices.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section contains a review of the literature that initially focuses on teams and team performance in information-intensive services, and subsequently on the emergence and effects of various team structures.

Section 3 profiles the case used in this study and outlines their procedures for claims handling.

Section 4 explains the methodology and rationale employed in the analysis of the data before

Section 5 presents the results of the work.

Section 6 presents a discussion of the results, including theoretical and managerial implications from the study, with a final sub-section acknowledging some limitations. Finally,

Section 7 and

Section 8 presents some limitations, conclusions, and suggestions for further research.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Teams and Team Performance in Information-Intensive Services

Salas et al. [

25] define a work team as “a distinguishable set of two or more people who are assigned specific roles or functions to perform dynamically, interdependently, and adaptively towards a common and valued goal/object/mission, who have each been assigned specific roles or functions to perform”. However, the inclusion of terms such as “adaptively” implies that team design can vary significantly across organizations, depending on their characteristics. Additionally, Babnik et al. [

26] assert that a combination of structural and socio-psychological characteristics of the environment in which teams exist influences their effectiveness and thus sustainability. Effectiveness is sometimes portrayed as comprising both viability and performance [

27]. Viability refers to the willingness to continue to work together by the individuals in the team [

28]. Performance, on the other hand, is more difficult to conceptualize [

29,

30], as it is constrained by the quality of the measures used to assess teams. Cohen and Bailey [

31] for example, assess team effectiveness using task, group, organization design factors, environmental factors, internal processes, external processes, and group psycho-social traits. Piña et al. [

32] stress that subjective measures must be balanced with objective measures developed by those external to the team.

Team design, on the other hand, is not an arbitrary concept. Defined by Stewart and Barrick [

33] as the “relationships that determine the allocation of tasks, responsibilities, and authority”, the configuration of teams is impacted by a wide range of constraints that affect performance, such as trust within the team structure [

34,

35]; skill differentials between leaders and team members [

36]; transformative effects of team training interventions [

37]; and intra-team relations, stability, autonomy, and team stress [

38,

39,

40].

Business process management (BPM) promotes a process-centric, customer-focused organization that aims to integrate and manage an organization’s people, processes, and technology [

15]. It is used by organizations to promote organizational efficiency and effectiveness [

15]. However, BPM is a complex endeavor and fraught with many challenges, often leading to failed initiatives. Prior work suggests that many of the reasons for failure relate more to human-centered rather than technology-oriented factors [

41]. Connecting the dots, the relationship between team design and business process management performance has also been observed [

42]. Some researchers have focused on examining how various team designs and their associated governance structures lead to different performance outcomes [

43,

44]. However, few studies investigate the influence of team design on the association between information-intensive processes and service performance. Teams and team design are a crucial component of business process management. Ambos and Schlegelmilch [

45] argue that an appropriate team structure is increasingly important, since an organization’s ability to process and co-ordinate information often depends on the teams’ capacity to make their own decisions. As a consequence, our study fills this gap by examining which team design is best equipped to deal with the information-intensive variables that affect the entire service performance.

Information-intensive services have an effect on team design [

20,

46]. The information intensity of a service is measured by the ratio of time spent dealing with information in a process, to the total time spent in that process [

20]. Therefore, as the levels of information inherent in business processes increase, then the manner in which that information is used for multiple tasks and exchanged within teams has an increased impact on team effectiveness, efficiency [

35], and ultimately sustainability.

Apte et al. [

20] argue that information plays three roles within a service—as an input, as an enabler, and as an output. However, Xiao et al. [

47] question the assumption that the sharing of information in teams leads to optimal decision outcomes. Their study emphasizes the difference between information sharing (the deliberate attempt of team members to mention information related to decision making) and information use (actual information considered when making decisions), and they find that there is a particular issue when information is unequally distributed. In such cases, information sharing does not facilitate optimal decision-making, whereas information use helps lead decision-makers towards optimal decision outcomes.

2.2. The Emergence and Effects of Team Structure for Sustainable Management

The discourse on team structures has evolved in two distinct directions and is not limited to service industries. The production line approach (PLA) to teamwork stems from concerns about service quality, and recommends utilizing thinking about a manufacturing process to simplify work tasks through a clear division of labor, that decision-making among team members is minimized, and that employees are replaced by technology where possible [

48]. This is consistent with Levitt’s [

49] seminal article, where he argued that customer service should be consciously treated as “manufacturing in the field”, so that it attracts the same kind of detailed attention that manufacturing receives.

Unsurprisingly, many subsequent commentators in the service science literature opposed this viewpoint. It is argued that service-dominant logic may be seen as a valid alternative to the traditional, goods-dominant paradigm that underpins much of our understanding of economic exchange and value creation [

50]. In this view, goods are seen as distribution mechanisms for service provision, while the “service” is the common denominator of the exchange process [

51]. Thus, many managers adopt a service perspective that facilitates mutual value creation for workers, suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders [

52].

In one comparative study, Apte et al. [

19] suggest that the production line approach is employed in manufacturing to yield consistent-quality standard products at relatively low cost, and that it is also employed in service firms in the hope of enjoying the same benefits. However, one of the key difficulties in comparing team design structures is measuring performance. The production line approach retains attractiveness for managers as it enables the possibility of finding the “one best way” to deliver a service, and it helps to avoid “systematic soldiering” where the pace of work is deliberately slowed by collective worker consensus [

53].

Meanwhile, the emergence of autonomous or self-managed work teams (SMWTs) was spawned from the evolution of socio-technical systems theory, which centered around the joint optimization of social and technical aspects of work [

54,

55]. SMWTs use the flexibility afforded by their autonomous nature to quickly adapt their task strategies in response to changes in the environment or to improve performance deficiencies. This aligns closely with the principles of the agile philosophy, in that they facilitate a flexible and dynamic approach that enables continuous delivery, requirement changes, and reflection [

56].

This enables them to diagnose problems and carry out appropriate remedies [

57]. The team itself bears responsibility for organizing the level of individual employee involvement and for motivating team members, and the team unit is empowered to decide the goals of team strategy, how effort should be coordinated, and how performance should be evaluated and rewarded [

58].

SMWTs are lauded to align well with sustainable management practices [

2,

3]. For example, they are sometimes hailed in the management literature as being transformative in the context of enhancing work–life quality, customer service, and productivity [

54], although the concept of autonomous teams has also been labelled as a “management fad” whose benefits are overstated [

59,

60]. The migration to a SMWTs structure requires much effort and intentionality, given that individuals are unlikely to automatically know how to work effectively in a team dynamic, while the absence of redundancy and conflict between team and individual autonomy may emerge [

61,

62]. Therefore, to avoid a dysfunctional operation, they may require assistance to diagnose internal structural misalignment, something that is often largely invisible to individual members [

57].

Research conducted at the nexus of information intensity in service industries and team structure is limited. Although Apte et al. [

20] examined information-intensive services, their primary focus was on identifying the variables that increased the intensiveness of the service, and not the impact team structure can have on an organization’s ability to manage the variables. Moreover, studies on the PLA and SMWTs have focused on the effectiveness of each structure in isolation. Therefore, the current research advances our understanding of information intensity in service industries by investigating its influence on the performance of claims handling services, as well as exploring how this impact differs between two team designs (PLA and SMWTs). It is proposed that this will have a significant impact on sustainable management.

3. The Research Case

3.1. Profile of the Organization and Claim Handling

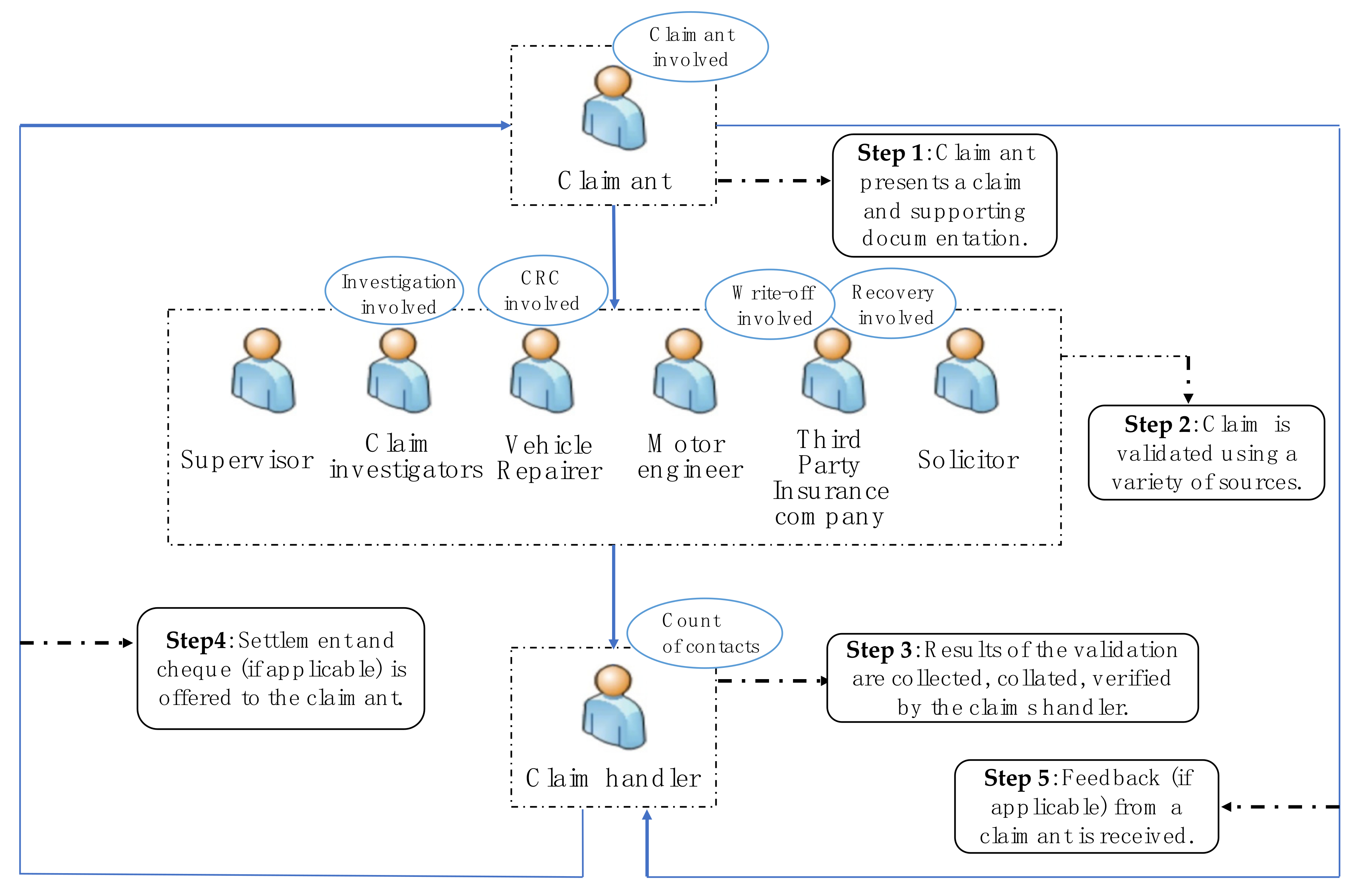

The subject of this case study is a large general insurance company operating in the Irish market. The claims handling team involved in the study deal with claims that are defined as low-value, high-volume motor claims, where adjudication on the question of liability has been determined before the team’s involvement. This means that, theoretically, it is possible to settle every claim assigned to the team, making it a suitable situation in which to examine the construct of efficiency. The team deals with a range of claim types, from normal motor accident claims to theft and fire claims, and the service is typical of any insurance claims handling function. In broad terms, the process contains five steps:

Claimant presents a claim and supporting documentation.

Claim is validated using a variety of sources.

Results of the validation are collected, collated, and verified by the claims handler.

Settlement and cheque (if applicable) are offered to the claimant.

Feedback (if applicable) is provided by a claimant.

Variability exists amongst cases because of the level of information intensity associated with the multiple parties involved at various phases of the claim. The core functions of the team include confirming indemnity, i.e., whether the customer is covered for the loss. They must also assess the estimated value and validity of the claim. This usually involves several service providers (e.g., motor assessors, engineers, repairers, claim investigators, and solicitors). Finally, once the claim’s validity and cost have been established, payment can be issued to the customer. The process is depicted in

Figure 1. It shows possible stakeholders and the potential information flows involved in the process. In this instance, it is apparent that the customer and the claims handler can interact not only with each other but also with several service providers and support functions. While

Figure 1 represents an extreme scenario in terms of engagement, it is feasible that this level of communication may arise regarding any claim. The pathways through which information might travel that contribute to the intensity level are not limited to exchanges between the customer and the handler, but also between the consumer and service providers, or even between related service providers (e.g., motor engineers and vehicle repairers).

3.2. Team Structures in the Case Organization

The unique opportunity afforded in this work stems from a change in team structure in the case organization. The researchers used a production line approach (PLA) to examine a yearly workload of 13,122 claims in the first of two years of claim data sampled for this study. The team comprised of 10 claims handlers. All claims were given generic names and all members of the team had equal responsibility for settling each claim. Additionally, the allocation of work was streamlined. Work was initiated by incoming documents (known as tasks) and phone calls. Management set priorities for each task and the enterprise system routed work based on these priorities to each team member sequentially. For example, the oldest outstanding task with the highest priority was pushed to the first member of the team, the second oldest task to the next team member, and so on. In relation to phone calls, the team operated a “hunt” system, whereby the handler who had been available to take a call for the longest period would be presented with the next phone call to the team. This meant that work was carried out in a strict sequence, and the overriding principle was to settle the oldest claim next. In order to ensure adherence to the process, supervisors could intervene and push specific work to claim handlers where necessary. Overall, the allocation of work was designed to “push” claims to settlement. This prevented claims handlers from picking and choosing which jobs they worked on. Another benefit was that the quality of service delivered to customers was consistent.

However, the organization then changed this team’s structure to align with the approach of self-managed work teams (SMWTs). After this new structure had been given time to become established, we analyzed a yearly workload of 11,803 claims settled by the team. The team, at this point, was of a similar size (n = 11), and included seven members who were also part of the team under its previous structure.

The team was divided into five sub-teams under the new format. Several improvements were made to enable the implementation of the self-managed work structure. Claims were assigned to each sub-team depending on the accident’s geographic location. The country (Ireland) was split up into regions and each sub-team took responsibility for claims within that region. The sub-teams had complete autonomy over the tasks they completed; all sub-teams were given access to the enterprise system, where they could see all of their outstanding work and make their own decisions about how to prioritize it. In the case of phone calls, each sub-team had their own “hunt” number, meaning they only dealt with calls for their own region. While they had the visibility of the outstanding work per team, supervisors did not intervene to ensure certain tasks were completed in a defined order, but rather they allowed the team to handle these issues and instead provided guidance and knowledge with regard to claim settlement.

The intention of the new team design was to empower employees and, in turn, motivate them to provide a higher level of service in line with sustainable management practices [

7]. An additional anticipated benefit was a more personalized service to the customer. However, the prospect that this type of team organization may result in some sub-teams being stronger than others, resulting in inconsistent service, was a source of concern. It raises the risk of claim handlers avoiding complex claims (the “systematic soldiering” effect), lengthening claim times and perhaps raising claim costs. The purpose of conducting this case analysis was to examine if this was the case or not and to ascertain which approach was more sustainable.

4. Method

The study’s research method was predominantly quantitative, since it allows for comparisons within the study and is more easily built upon by future studies. The initial challenge with this approach was the absence of a set of pre-ordained measurement variables. This necessitated an initial qualitative exercise involving consultation with claim handling team members, management in the subject organization, and academic colleagues. This process aimed to establish essential claims handling performance metrics in addition to several information-intensiveness measures that were both relevant and visible, as well as accessible for two time periods and team designs. The result was a list of eleven indicators, two of which are measures of performance (dependent variables), six measure factors contributing to the information intensity of the claims handling process with the remaining three serving as additional key performance indicators for claims handling teams. An explanation of each measure and the rationale behind its inclusion in the study are outlined in

Table 1 below.

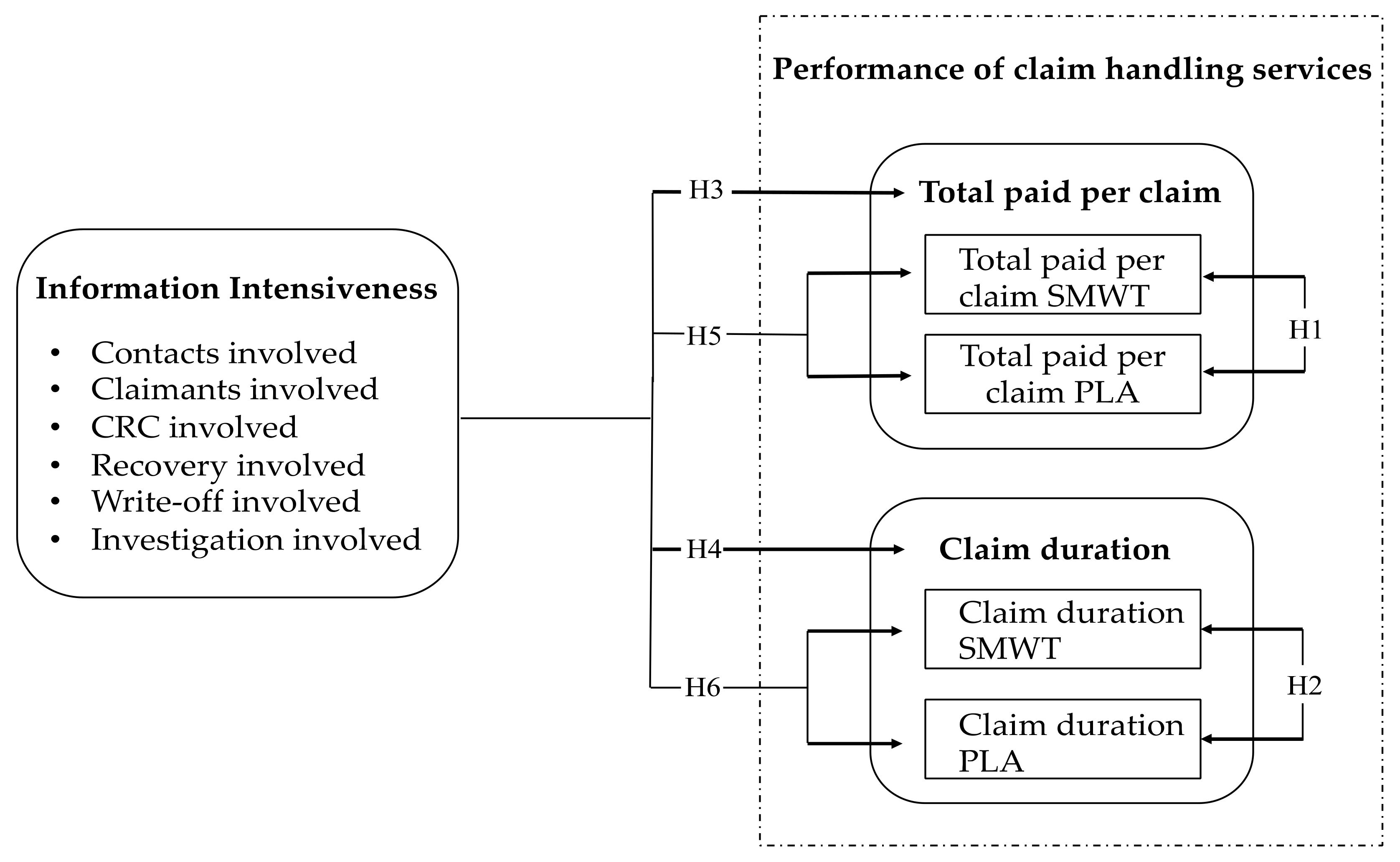

The six information-intensiveness variables were recorded for both of the time periods. However, to suit the objectives of this study, the key performance variables were recorded separately for each team type and were described as total paid per claim SMWTs and total paid per claim PLA for the self-managed work teams and the production line approach, respectively. A similar approach and naming convention were adopted in the case of the claim duration variable, leading to the development of the hypotheses depicted in

Figure 2.

At the outset it was decided to explore both service-related performances using two separate datasets to establish how they behaved under the two different team structures, thereby proposing the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. There is a significant difference between the total paid per claim under an SMWTs structure and a PLA structure.

Hypothesis 2. There is a significant difference between the claim duration under an SMWTs structure and a PLA structure.

Then, the effect of information-intensiveness was proposed.

Hypothesis 3. Information-intensiveness has a significant impact on the claim duration.

Hypothesis 4. Information-intensiveness has a significant impact on the total paid per claim.

Finally, the two datasets were compared to see how each of the variables that contribute to information-intensiveness influenced each of the two essential service deliverables, resulting in the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5. Information-intensiveness has the same impact on the claim duration under an SMWTs structure and a PLA structure.

Hypothesis 6. Information-intensiveness has the same impact on the total paid per claim under an SMWTs structure and a PLA structure.

5. Results

5.1. Team Structure and Service Performance

Hypotheses one and two were tested using the independent

t-test. The independent

t-test is an inferential statistical test that is widely used to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference between the means in two unrelated groups [

63]. Our study therefore used this method to investigate how each team structure (SMWTs and the PLA) compares across the performance in a claim handling service. The results are illustrated in

Table 2. As shown in it, there is a significant difference between the mean total paid per claim under an SMWTs structure and a PLA structure (t = −6.002,

p < 0.05). Hypothesis one (there is a significant difference between the mean total paid per claim under an SMWTs structure and a PLA structure) is therefore confirmed. Moreover, on average, the PLA had a higher paid to date (mean (M) = EUR 3243.04; Std. error mean (SE) = 37.51) than the SMWTs (M = EUR 2927.26; SE = 36.90). Hypothesis two (there is a significant difference between the mean claim duration under an SMWTs structure and a PLA structure) is also confirmed on a similar basis. On average, SMWTs had a higher claim duration (M = 88.01 days; SE = 0.93) than the PLA (M = 77.69 days, SE = 0.75). This difference was significant t (23,320.83) = 8.619,

p < 0.05.

5.2. Information-Intensiveness and Claim Duration

Concerning hypothesis three (information-intensiveness has a significant impact on the claim duration), the results are illustrated in

Table 3. First, linear regression tests were used. This approach allowed us to assess the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Specifically, it helped us to determine whether the predictor variables (e.g., number of contacts or claimants) explained the dependent variable (e.g., claim duration). The results of both tests were deemed significant (contributing to the formal confirmation of hypothesis three,

p < 0.05). Concerning the number of contacts per claim, the coefficient of determination (R

2) value was 0.104, which means that the number of contacts added to a claim accounts for 10.4% of the variation in the claim duration. The results also convey that for every contact added, the claim duration increases by 3.89 days. The R

2 value for the number of claimants added was 0.029, i.e., it accounts for 2.9% of the variation in claim duration. It implies that for every claimant added, the claim duration increases by 37.01 days. Second, independent

t-tests were conducted to examine the impact of situations where other information-intensive variables are involved (i.e., CRC, recovery, write-off, and investigations). This inferential test allowed us to compare the difference in the results. For example, it enabled us to ascertain whether there was difference between the outcomes if CRCs were involved or not, whether recovery was involved or not involved, whether write-off was involved or not involved, as well as whether investigations were involved or not. In hypothesis three, we expect that a situation with CRC, recovery, write-off and investigations involved to effect the claim duration. As illustrated in

Table 3, each variable contributes to the overall confirmation of hypothesis three because a significant difference was found for each test (

p < 0.05). Furthermore, Cohen’s [

64] measure of effect (r) was also employed in our study as it is lauded to be a good method to examine the size of the relationships between variables. In

Table 3, the results show that when a CRC is involved, the claim duration is shorter (medium effect size of 0.33); they also confirm that when recovery is involved, the claim duration is higher (medium effect size of 0.45). When a vehicle is written-off during a claim, the duration tends to be higher, but not very significantly (small effect size of 0.12). Where an investigation is required, the claim duration increases but not very significantly (small effect size of 0.02)

5.3. Information-Intensiveness and Total Paid Per Claim

In examining hypothesis four (information-intensiveness has a significant impact on the total paid per claim), the linear regression and independent

t-test were also conducted (see

Table 3). As shown in

Table 3, linear regression tests were used to test whether the number of contacts or claimants impacts the total paid per claim. The results of both tests were deemed significant (contributing to the formal support of hypothesis four,

p < 0.05) and represent a valid approach (ANOVA and coefficient,

p < 0.05). The R

2 value concerning the number of contacts is 0.170, or 17%, which is quite high. The results also confirm that for every contact added to the claim, the total paid increases by EUR 207.59. In relation to the number of claimants added to the claim, R

2 is 0.04, or 4%, which is quite low. However, for every claimant added to the file the total paid increases by EUR 1,861.79. Moreover, independent

t-tests were used to test the impact of situations where the other information-intensive variables are involved, i.e., CRC, recovery, write-off, and investigations. Each variable contributes to the overall confirmation of Hypothesis 4 as a significant difference was found for each test (

p < 0.05). When a certified repair center (CRC) is involved in a claim, the total paid is lower; however, the measure of effect (r) is small (0.12). The total paid is higher when a financial recovery is involved, but again the measure of effect is small (0.18). In addition, when a vehicle write-off is involved in a claim, the total paid remains higher, but the measure of effect is large (0.52). Finally, when a claim is investigated the total paid is higher and the measure of effect is medium (0.42).

5.4. Information-Intensiveness and Service Deliverables under Different Structures

To determine how each team structure performs concerning the performance of claims handling services, claim duration, an identical set of statistical tests to those mentioned above were carried out separately on the two datasets, separated by team type. The results are summarized in

Table 4 below.

As illustrated in

Table 4, hypothesis five (information-intensiveness has the same impact on the mean claim duration under an SMWTs structure and a PLA structure) is not supported. Because the results show that information-intensiveness has a greater impact on claim duration under the SMWTs design; for example, when it comes to SMWTs, the number of contacts added to the claim can explain 15.5% of the variability in claim duration; this figure is considerably higher than that for the PLA (5%).

Similarly, to determine how each team structure performs in relation to the total amount paid per claim, an identical approach was adopted, and the results are presented in

Table 4. Although the variance in the results for both team structures is not as dramatic as for claim duration, they still allow for the rejection of hypothesis six (information-intensiveness has the same impact on the total paid per claim under an SMWTs structure and a PLA structure).

5.5. Post Hoc Analysis on Team Structure and Operational Efficiency

A further level of analysis was performed on the two datasets using the additional performance indicators identified in

Table 1, namely claims settled per hour, cheques requested per hour, and cheques authorized per hour worked. Independent

t-tests revealed that the PLA performs better than SMWTs. While the measure of effect differs for each indicator, the findings are statistically significant. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that the PLA resulted in a higher number of claims settled per hour worked (small effect size, r = 0.15), a higher number of cheques requested per hour worked (medium effect size, r = 0.45), and more cheques authorized per hour worked (medium effect size, r = 0.36).

6. Discussion

This study set out to determine whether information-intensive processes impact the performance of claims handling services and whether the impact of information-intensive processes differs according to the team structure adopted. The findings indicate that information-intensive processes have an impact on the claims handling service and that there is a difference between the degrees of impact under each team structure. The findings also show that the PLA structure resulted in a lower mean claim duration, but a higher mean in relation to the total paid per claim. It confirms the merit in exploring the difference between both team structures as it has an impact on sustainable management practices.

The variable that had the greatest impact on both service performances was the number of contacts added to the claim. As shown in

Table 3, it accounted for 10.4% of the variability in claim duration and 17% of the variability in relation to the total paid per claim across the entire data sample. This result is logical, in the sense that complex claims result in more validation and thus the necessity to communicate with all parties involved increases. Apte et al. [

20] examined the impact of information intensity on a claims handling service and found that the involvement of an attorney on a claim had the greatest impact on the information intensity of the service; they also show that the longer it takes the company to contact the customer, the more likely they are to employ an attorney. While the current research did not make distinctions between the type of employment carried out by the contacts involved in claims, our finding corroborates Apte et al.’s [

20] general result. An additional point of interest is shown when the data relating to each team structure are analyzed in isolation: under the PLA, the addition of a contact only accounts for 5% of the variability in claim duration, compared to 15.5% under SMWTs (see

Table 4). A possible conclusion, therefore, is that the structure of the PLA lends itself to better management of contacts, i.e., the sequential allocation of tasks to claims handlers appears to have a more positive impact on the claim duration. There is no real difference in relation to the impact on the total paid per claim (PLA = 17.7%, SMWTs = 18.10% in

Table 4).

As the number of claimants increased so did the claim duration and the total paid per claim. The significance also differed between team structures: under the PLA the number of claimants only accounted for 1.5% of the variability in the claim duration, whereas under SMWTs the result was 5.3% (see

Table 4). The results would indicate that the PLA is better placed to deal with the information intensity arising from an increase in claimants. Once a certified repair center (CRC) became involved, both the claim duration and total paid per claim were reduced, thus confirming another positive correlation between information intensity and the service deliverables. There was no real difference between each team structure; it had a medium impact (0.31 and 0.32 for the PLA and SMWTs, respectively) relation to claim duration and small impact (0.09) with regard to the total paid per claim for both team structures (see

Table 4).

In situations where it was possible to recover funds from another insurer, there was a significant impact on increasing the claim duration (0.45 effect size), whereas the impact on the total paid per claim was small (0.18 effect size) (see

Table 3), which again is intuitive, i.e., the necessity of recouping outlay would not impact the amount paid in the first instance. The effect on the claim duration was the same per team structure, at 0.47 (see

Table 4). While this result makes no distinction between the PLA and SMWTs, it does show the importance of being able to manage financial recoveries efficiently concerning the service itself. In order to stress this importance, it is worth noting that if recovery situations are not handled effectively by the team they have financial implications for the organization (in terms of lost revenue) and the policyholder (in terms of an increased premium). When a vehicle is written off during a claim, it has negative implications for the claim duration and the total paid per claim, although the effect is small, at 0.12 (see

Table 3). Interestingly, when it came to claim duration, there was no significant effect found under the PLA, whereas there was a significant effect found under SMWTs, at 0.24 (see

Table 4).

These results indicate that PLA was often better placed to manage the claim duration when a vehicle was written-off in a claim. The variable had a statistically large effect on both team structures concerning the paid to date; the effect size was 0.52 (see

Table 3). This can be validated by the fact that claims where a vehicle is written off result in more damage and therefore higher costs.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study progresses the work of Apte et al. [

20]. Although both studies are similar in identifying variables that impact performance metrics/service deliverables, with similar results, the current study goes one step further. By comparing how team structure can alter the degree of influence that information intensity can have on service deliverables, we are extending the work of prior scholars. Our analysis of the key metrics, in this case for separate team structures, has shown that the performance of each structure differs. These findings have an impact on how managers and decision-makers design structures to enable increased performance, efficiency, and sustainability.

Our analysis found that claim handlers working under the production line approach (PLA) paid out more to the claimant in comparison to those working under the self-managed work teams (SMWTs) approach; however, claims took longer to settle under the SMWTs structure in comparison to the PLA system. The study conducted by Bowen and Lawler [

48] suggested that the PLA was beneficial when the service provided required a high degree of knowledge intensity. The findings in our study indirectly support this notion; i.e., for example, in cases where an investigation was required, the necessity for increased knowledge naturally increases, i.e., the claims handler needs to understand how to interpret the results of the investigation and then know what questions need to be answered to progress the claim. Similarly, the PLA also performed better when the number of contacts increased on the claim. The number of contacts is an indicator of the increased level of information flow, and the requirement to disseminate information and knowledge to more parties involved in the claim’s chain. Therefore, while consistent with prior research, this study generates its own contribution to theory by examining the effects of a series of information intensity factors on team types.

This study is also of significant theoretical importance in presenting an opposing viewpoint to the traditional beliefs about sustainable team design. Specifically, a classic study conducted by Schneider and Bowen [

65] argued that empowered workers were more productive than their counterparts who operate under the PLA. Similarly, Kim et al. [

66] argued that for teams to be effective in a service-based industry, empowerment was a necessity. In this study, we find a more nuanced outcome, whereby in certain contexts the production line approach was more productive concerning key operational tasks completed per hour than SMWTs approaches.

6.2. Managerial Implications

The study shows that although different types of team structures may be presented, or indeed inherited, by managers, it is important that the type of team design implemented aligns with the requirements of service provision and takes into account the amount and level of information handled. This is especially true in claims handling, which is characterized by information intensity and customer contact intensity, but is relatively light in terms of material intensity [

20].

The findings from this study showing how the number of contacts added to a service can have a significant impact on key deliverables, irrespective of team structure, implies that management should examine the number of contacts, and the point at which they join the process, to see when they have the greatest impact. Once these are identified, the processes can be reviewed and those contacts can be dealt with first, providing the organization with the opportunity to measure the effectiveness of any process changes arising from a review of contact selection.

When dealing with customers who can have varying demands, service providers should ensure that the structure of the team is compatible with nature of the work being conducted. For example, in our case analysis, if a customer has agreed to use a CRC to repair their vehicle, it could be worthwhile meeting this request even if it is outside of standard practice. Our analysis suggests that the use of the CRC will have a significantly positive effect on the claim duration and the total paid per claim. Therefore, if management can identify the criteria by which work practice variation may be facilitated and align this with specific team structures that are deployed in the claims handling process, this flexible approach may return claims that are less expensive or are of shorter duration.

The proliferation of “white label” insurance products has resulted in several providers attempting to standardize the claims service by limiting the extent of policy coverage. For example, in some cases, the customer may only avail of car hire if they use an approved repairer. The benefits to the insurer are obvious: the service is standardized and the costs can be managed more effectively; however, while most customers accept the theory of “you get what you pay for”, they rightly still expect the service to be very professional. The approach taken in this study allows management to identify which aspects of the service need to be protected by strict policy conditions and which may be interpreted more widely.

Finally, management may consider using a similar approach to the above study to investigate the performance of different teams that handle more complex claims. Analyzing which team structure is better as claim complexity increases, in terms of cost, time and number of contacts, for instance, may determine a threshold where changing the team structure may become feasible. Such a threshold, were it to be developed, may be temporary in nature to deal with peaks and troughs in claims that are processed, and may be influenced by some external factors.

7. Limitations

Because the study objective was not to determine the superior team design, but rather which design is better placed to handle information intensity, we did not take into account non-information-intensive variables, such as levels of employee satisfaction. Moreover, our research hypotheses were driven by a specific case rather than theory-based reasoning. Although this perspective provides context-specific insights from a unique and under-researched situation, the generalizability of this study is somewhat limited. We thereby encourage future studies to extend this line of research by focusing on theory-based hypotheses and investigating more contexts with wider samples.

It could be perceived that the quantitative approach taken was more sympathetic towards the PLA. Some of the traditionally identified benefits of SMWTs are based around the aforementioned qualitative aspects of team structure. For example, SMWTs are perceived to increase motivation within teams, which leads to better personal development within the organization. It would be unreasonable to suggest without foundation, however, that because the PLA managed the service deliverables better, that it is because employees were highly motivated to do so.

Additionally, the data in this study were from two distinct time periods, so the effects of time-based external factors cannot be ruled out. The Irish economy dipped into recession during the time in question, with a direct consequence being the availability of cheaper labor within the motor industry. Similarly, weather conditions immediately before the second sample were taken were more extreme than previously, which may have resulted in a surge in claims and a consequent increase in pressure on claims services.

Since the type of claims the team handles in this study are quite limited in terms of complexity, the service provided is relatively standardized. It could be argued that the selection of claims for the study has leveraged the positive PLA results achieved; and that a wider range of claim types may alter the findings in favor of more self-managed work team behaviors. This indeed would need to be accounted for in future studies. However, the findings did show that once information intensity increased, PLA was still able to manage the service concerning the key service deliverables that were measured.

Finally, it should also be acknowledged that regulatory and commercial demands, within the industry, increased significantly during the years of the study. As a result, there were greater demands on claims handlers regarding not only the number of processes they are required to adhere to but also the necessity to ensure customer satisfaction remains higher than ever before.

8. Conclusions and Further Research

The continual growth of the information economy will place a heavy burden on organizations to not only gather and store larger volumes of information but also to process this information in a fashion that is operationally efficient. This has an impact on sustainable team design in the service industry. The way service teams are designed will play a significant role in organizations’ ability to generate sustainable competitive advantages [

2,

3]. Many organizations take a simplistic “call center” approach to team design; that is, they create large teams who deal with queries and processes as they are presented to them, often with no attempt to identify the processes that create bottlenecks or result in a poor-quality service. Persisting with this approach is no longer tenable. With the growing complexity of call centers, the achievement of consistently high levels of service quality and efficiency has become more difficult [

22]. Thus, one of the dilemmas facing many service organizations is ensuring that the team structure aligns with the nature of the business processes in an efficient, effective, and sustainable way.

Our research findings underlined the value of PLA team structures when they occur in specific contexts. For example, our study provided evidence to suggest that the PLA team structure was more effective than the SMWTs structure in a claim handling service in the motor insurance industry. This case depicts a complex information-intensive service as information must be gathered, processed, and distributed to, and from, multiple actors, such as claimants, supervisors, claims investigators, vehicle repairers, motor engineers, insurance, and solicitors, as well as claims handlers. In addition, we found that the PLA team structure was more effective than the SMWTs structure when specific parameters were examined. We investigated the influence of information intensity on objective service performance parameters (e.g., the total amount paid per claim and duration). We did not investigate subjective performance outcomes such as employees’ satisfaction and wellbeing, which could have yielded different results.

Future research in this area, should, in the first instance, address the areas identified as limitations in this study. In addition, the context-specific nature of some of the findings of this study implies that subsequent studies need to be focused on specific contexts to be meaningful. For example, in the service discussed in this study, there is a heavy reliance on external service providers to participate in the service, i.e., the claims handler could be dependent on receiving information from a motor assessor, claims investigator, or approved repairer, among others. The way external participants carry out their functions will impact the service deliverables. For instance, if a motor assessor does not submit their report in a timely fashion, there is a high likelihood that the claim duration will increase. In many respects, such requirements are out of the hands of the claim’s handler, and by extrapolation outside of the influence of any team redesign. This suggests a particularly ripe avenue for future research—to investigate the direct impact third-party service providers have on information-intensive services. For instance, a study could be conducted to review how compliance (or non-compliance) with service-level agreements help determine the level of service actually delivered to the final customer. Furthermore, it is necessary to analyze the nature and effectiveness of service processes (e.g., claims handling) on an ongoing basis in order to ensure that emerging constraints and innovations such as changes in the law, advances in automation, changes in social culture, etc. are incorporated. We therefore recommend that future studies could use process mining techniques to analyze processes and consequently optimize efficiency and effectiveness. Moreover, lean six sigma is a continuous improvement approach lauded to enhance performance by systematically removing waste, reducing variation, and enhancing an organizational culture conducive to continuous improvement [

67]. Therefore, we encourage future researchers to implement and analyze the use of specific lean tools (e.g., value stream mapping, kaizen, and poka-yoke). Moreover, factors that are critical to the success of lean initiatives such as leadership, empowerment, and culture deserve further attention.

This study also suggests that there is merit in studying the performance of a range of different teams who handle more claims with varying levels of complexity. Analyzing which team structure is better as claim complexity increases, in terms of cost, time and number of contacts, may determine a threshold where changing the team structure may become feasible and sustainable. Moreover, the evolving customer-centric approach to business process management merits further investigation of dynamic management approaches and their role in BPM. We therefore encourage future researchers to consider analyzing the crossovers and connections between business process management and agile team design in addition to dynamic management approaches, as well as its influence on team performance.

In summary, while this study sheds light on a relatively unexplored aspect of service industry provision, it also offers up a rich vein for potential future studies, all of which can enable sustainable management practices.