Abstract

Drawing on motivating language theory (MLT), this paper aims to demonstrate the effects of strategic leader speech in the context of internal corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication. Specifically, the study (1) examines how leader motivating language strategies used in CSR communication influence employees’ CSR engagement and employee–organization relationships (EORs) and (2) identifies the mediator explaining the underlying psychological mechanism of the effects. Structural equation modeling was performed on a sample of 406 participants who are full-time and part-time employees in the U.S. The results showed that leader motivating language was positively associated with employees’ CSR engagement and EOR quality. Such relationships were significantly mediated by person–organization (PO) fit. This study advances CSR research and practice by explicating the impact of leaders’ oral communication in constructing employees’ CSR experiences and relationships with the employer.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become a core corporate value demanded by the younger generation of the workforce [1,2]. Recent statistics show that 88% of millennials are concerned about their companies’ CSR and 86% would consider leaving if their employers’ CSR initiatives are under their expectations [3]. Previous research has suggested that employees’ positive perceptions of and involvement in companies’ CSR activities can facilitate employee morale [4], enhance job satisfaction, foster positive attitudes towards the employer [5], and increase employee–organization identification and organizational commitment [6,7].

Given the importance of engaging employees in CSR, a more urgent and practical question would be how to better motivate employees in organizational CSR activities [8]. Yet, factors contributing to employee CSR engagement is still a relatively understudied area [9]. Previous studies also argued that CSR offers a pathway to build organization–public relationships [10,11], but less is known regarding how CSR communication contributes to employee–organization relationship management. Despite recognizing the importance of employee CSR engagement, previous studies rarely examined the role of leaders’ use of rhetorical skills and language in motivating employees’ CSR engagement and fostering quality employee–organization relationships (EORs). To address this gap, this study aims to address the overarching question: How do leaders’ languages in CSR communication affect employees’ multidimensional CSR engagement (i.e., emotional, cognitive, and behavioral) and relationship quality with their employers?

Internal communication refers to top-down communication between leaders and employees aiming to align employees with an organization’s values and objectives and enhance employee engagement [12,13]. Leaders play a critical role in initiating and facilitating the conversations on internal matters. Previous internal communication and CSR research has focused on the impacts of leadership styles and communication models in promoting CSR with internal stakeholders [14,15], but the linguistic or rhetorical aspects have been largely overlooked. This gap is concerning because leaders’ oral communication can powerfully affect employees’ psychological and relational states, ultimately motivating their behaviors and relationship building with companies [16,17]. Leaders’ languages also account for 70–80% of their managerial work [17], which is imperative to foster a supportive and motivating environment for employees to undertake initiatives for both jobs and non-job related organizational behaviors [16,17,18].

Drawing on motivating language theory (MLT), this study examines how leaders’ oral communication strategies (i.e., direction-giving language, empathetic language, and meaning-making language) affect employees’ CSR engagement and relationship with the employer. Rooted in speech act theory [19], MLT focuses on using strategic motivating languages to alleviate ambiguity and create social connections between the employer and employees [20]. While MLT has been studied in internal communication [21,22], few have examined its application in the CSR context, especially from a stakeholder’s perspective. Answering J. Mayfield and Mayfield (2017)’s call of specifying context in MLT research [23], this study contextualizes MLT in internal CSR and argues that leaders’ direction-giving language, empathetic language, and meaning-making language have great potential to enhance employee CSR engagement and foster EORs.

In addition, to reveal the mechanism through which MLT influences employee CSR engagement and EORs, this study argues that PO fit plays a mediating role. Focusing on value congruence, PO fit has been identified as an antecedent for employee engagement and positive relationships with companies [15,24,25]. Although previous literature suggested the influence of PO fit in fostering employee engagement and positive organizational outcomes [15,25,26], such effects have rarely been studied under the influence of internal communication strategies. By analyzing the mediating effect of PO fit, we can articulate the path through which leadership communication affects employees’ psychological and behavioral responses to CSR, as well as their perceived relationships with the employer.

This study is an early attempt to contextualize leader motivating language in CSR. As the glue that binds internal and external CSR stakeholders, CSR communication studied from a MLT perspective fills a gap in the literature through its multidimensional use of an interpersonal and rhetorical communication lens. Leaders’ persuasive oral communication about CSR can positively influence employees and generate an array of desirable outcomes. MLT applied to CSR could result in a deeper understanding of employee engagement in CSR programming and a stronger conceptualization of how leaders inspire a shared sense of values. Incorporating PO fit as a mediator, this study attempts to develop a model delineating how leader motivating language in CSR can, directly and indirectly, influence employees’ CSR engagement and EORs. Practically, our findings provide guidance for leaders to develop oral communication skills to better engage with employees through CSR activities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Background: Internal CSR Communication

CSR encompasses a range of corporate positions on how to be socially responsible to society. Carroll’s (1991) long-standing CSR model defines it as four types of corporate initiatives for responding to societal expectations: economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities [27]. While external CSR communication is well studied, communication about CSR internally is less understood. Internal CSR communication can be defined as employer-to-employee communication about CSR endeavors [28]. Internal CSR communication is a budding area of public relations research for recognizing the value in closing one-way information dissemination in favor of symmetrical communication between organizations and employees. Internal CSR communication has many potential benefits. Jiang and Luo (2020) found that internal CSR communication from leaders to employees via websites, newsletters, announcements, corporate events, or social media outlets can generate positive employee outcomes at attitudinal, affective, and behavioral dimensions [29]. Internal CSR communication has also been studied in the business leadership communication literature. In a study of 298 employees from a variety of industry sectors, Afsar et al. (2018) found that the managerial role of internal CSR communication could activate pro-environmental behaviors in employees [30].

2.2. Motivating Language Theory (MLT)

Motivating language theory (MLT) was initially termed “motivational language” by Sullivan (1988), highlighting the positive influence of leaders’ spoken messages on employees’ motivations in the workplace [31]. Sullivan (1988) posits that the content of messages in leadership communication is significantly associated with followers’ motivations [31], which ultimately affects their job performance, satisfaction, commitment, and other desirable outcomes [21]. J. Mayfield and Mayfield (1995; 2009; 2017) further advanced the theory and contend that MLT could engage employees with positive outcomes for both organizations and individuals [23,32,33]. MLT drives employees’ motivations by employing a wide spectrum of oral communication and is rooted in the linguistic dimensions of direction-giving, empathetic, and meaning-making language.

Direction-giving language is used by leaders to reduce the ambiguity of tasks and roles, encourage task-related behaviors, and explicate how employees benefit by doing so [23,32]. This dimension highlights clear job vision and goal setting, informational transparency, constructive feedback, and reward contingencies [23], which are conducive to enhancing employees’ work quality, effectiveness, and efficiency. This dimension posits that employees feel motivated when there is clear communication regarding goals and rewards attainment from leaders.

Empathetic language focuses on employees’ overall human caring rather than showing empathy toward task-related events alone. By demonstrating polite attitudes, understanding, and emotional support toward employees, leaders can forge interpersonal bonds with employees [23]. Empathetic language is congruent with the person-oriented behavioral management in leadership literature [34]. This dimension suggests that employees feel supported when leaders verbally put themselves into employees’ perspectives. While engaging with employees, an empathetic leader will actively listen to employees and share relevant stories, including both positive feedback and compassion in stressed situations.

Meaning-making language occurs when leaders fulfill an employee’s need to understand the meaningfulness of work and to transmit organizational vision, values, expectations, and cultural norms [31,32]. Meaning-making language can be informal, such as through the use of metaphors. This dimension informs employees that what they do is valued and informs how they contribute to the big picture of the organization’s development [23]. Rooted in sense-making theory [35], meaning-making language can motivate employees when they feel what they do is meaningful and significant. Meaning-making language also includes sharing cultural norms via stories [23]. This dimension is especially critical when organizations experience change and when leaders are required to introduce new cultural norms and visions [36].

The scale of three linguistic dimensions has been validated and operationalized in different countries, including the U.S., Mexico, and Mainland China [16,20,37]. As an effective antecedent in internal communication, MLT has shown positive effects on a variety of employee outcomes at an individual level, including job performance [22], employees’ perceived leadership communication competence [38], organizational commitment and job satisfaction [37], employee decision making [39], and self-leadership [21], as well as negative effects on absenteeism [40] and intent-to-turn-over [41]. Scholars have also advanced MLT applications to organizational outcomes. Holmes (2012) found a positive relationship between MLT and organizational performance [42], and Ling and Guo (2020) found a positive cross-level effect of motivating language at the team level on employees’ personal initiatives [16]. This study conceptualizes MLT in the context of CSR, highlighting how leaders’ oral communication in CSR influences desirable employee outcomes, employee CSR engagement, and EORs.

2.3. Employee CSR Engagement

Employee engagement has received increasing attention across disciplines, including management, psychology, and public relations. Although it has been variously defined for different research purposes [43,44,45,46], many later definitions were built on Kahn’s (1990) personal engagement [44,46,47]. Kahn (1990) defined personal engagement as “the harnessing of organization members’ selves to their work roles; in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances” [44] (p. 694). Similarly, Sonae et al. (2012) identified three psychological dimensions of employee engagement: cognitive, emotional, and social (behavioral) [47]. Thus, conceptualizing employee engagement with three dimensions—emotional, cognitive, and behavioral—is widely accepted.

Even though employee engagement has been shown to be a positive outcome of internal CSR communication [28], specific investigation into employee CSR engagement as a concept has been limited. Operations of CSR engagement at the behavioral level only count frequencies and number of hours employees devote to CSR activities [9]. For instance, Chen and Huang-Baesecke (2014) suggested a positive link between leadership and employee CSR participation [14]. Lee et al. (2019) indicated that CSR awareness was positively related to employees’ CSR behavioral intentions [48]. Koch et al. (2019) extended CSR participation from the behavioral dimension to two perspectives, including both cognitive and behavioral [9]. Nejati et al. (2020) employed the term employee CSR engagement, but it only touched upon the emotional perspective [15]. Hurst and Ihlen (2018) proposed three dimensions of CSR engagement, including commitment, mapping of responsibilities, and closing the loop [49]. However, Hurst and Ihlen’s (2018) three dimensions lacked operationalizations for empirical studies [49]. A brief summary suggests a lack of development of conceptualization and operationalization of employee CSR engagement.

Given that one of this study’s interests lies in examining the relationship between leader motivating language and employee CSR engagement, this study employs definitions of employee CSR engagement from Kahn (1990) and Sonae et al. (2012) [44,47], and conceptualizes employee CSR engagement covering the spectrum of three psychological dimensions: emotional, cognitive, and behavioral. Emotional CSR engagement refers to employees’ positive affect relating to CSR initiatives. Cognitive CSR engagement refers to employees’ mindful and intellectual attention to CSR initiatives. Behavioral CSR engagement refers to employees’ physical connections with CSR initiatives [47].

Internal communication from management levels has been identified as an important driver of employee engagement [50,51,52]. Mayfield and Mayfield (2016) proposed that motivating language can increase employee engagement, connecting with employees’ better decision-making at the workplace [39]. Recently, Rabiul and Yean (2021) conducted a survey which found positive associations between direction-giving, empathetic, and meaning-making language and work engagement, respectively, which confirmed that leader motivating language in reducing task-related uncertainties, emotional support, and meaning-making could produce positive employee outcomes [53]. However, work engagement was a uni-dimension measure in their study. Rodell (2013) explained that behavioral participation alone cannot fully present the engagement dimension [54]. We believe our multidimensional conceptualization and operationalization of employee CSR engagement can complement previous studies.

Consistent with the positive relationship between leader motivating language and employee engagement, we expect that the better leader motivating language in CSR is, the more engaged employees are with CSR. Direction-giving language articulates tangible goals and rewards that help employees understand what they are expected to accomplish and how they will be rewarded for CSR engagement. Empathetic language makes employees feel emotionally supported in CSR engagement. Being involved in CSR activities has potential conflicts with family responsibilities and work-related performance [55]. Employees who engage with CSR need leaders to communicate their emotional support. Finally, meaning-making language shows employees how their CSR engagement could fit cultural norms and align with the larger organizational goals, thus encouraging them to engage in the company’s CSR initiatives. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Leader motivating language in CSR is positively associated with employees’ CSR engagement.

2.4. Employee–Organization Relationships (EORs)

The concept of organization–public relationships (OPRs) originated from public relations focusing on building and maintaining relationships with different stakeholders [56]. Huang (1998) defined OPR as “the degree that the organization and its publics trust one another, agree [that] one has rightful power to influence [the other], experience satisfaction with each other, and commit oneself to one another” [57] (p. 12). Relationship management theory contends that managing organization–public relationships shares common interests for both organizations and the public [58]. Thus, fostering high-quality relationships with stakeholders is crucial to organizations. As one of the most important internal stakeholders, an organization’s relationship management with employees is imperative to the organization’s reputation and success. On the one hand, good EORs can influence employees’ productivity, ultimately affecting the organization’s financial performance and development [59]. On the other hand, employees are regarded as credible sources for external stakeholders to know the organization [60]. What employees say about an organization influences others’ impressions of the organization [51]. Thus, high-quality EORs are conducive to the relationships between organizations and external stakeholders [61].

Aligning with previous research in public relations [50,60,62], this study contextualizes OPR in the employee relations as EORs. Specifically, this study adopted Hon and Grunig’s (1999) conceptualization and Kang and Sung’s (2017) operational definitions of three dimensions of trust, satisfaction, and commitment for EOR [50,63]. Trust highlights how reliant employees on their organization; commitment focuses on how employees feel belonging to their organization; and satisfaction detects how satisfied employees feel with their relationship with their organization [50].

Although recent years have shown research exploring the relationships between employees’ CSR perceptions and the quality of EORs, little is known about how leader motivating language can influence EORs. Internal communication has been identified as an important antecedent for positive EORs [64]. Previous research has demonstrated the positive effects of leaders’ communication competence and style on EORs [51,60,65,66]. Madlock and Sexton (2015) examined MLT in Mexican organizations and suggested MLT was positively associated with leaders’ communication competence, employees’ job satisfaction, and organizational commitment [37]. Leaders paying attention to relationship-oriented outcomes are employee focused, who are more likely to empower and motivate employees through emotional support and fulfilling employees’ special needs [67]. Since MLT highlights employee-centered communication, it can be inferred that leader motivating language in CSR helps lead to more employee trust, commitment, and satisfaction with their company, ultimately forming high-quality EORs:

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Leader motivating language in CSR is positively associated with employee–organization relationships (EORs).

2.5. Person–Organization Fit (PO fit)

PO fit is defined as “the compatibility between people and organizations that occurs when at least one entity provides what the other needs, they share similar fundamental characteristics, or both” [68]. PO fit concerns whether there is consistency between an employee’s personal values and an organization’s values, cultures, and goals [69]. The theoretical underpinning of PO fit is that employees’ attitudinal and behavioral outcomes do not result from the individual or the organization alone, but rather from the relational interactions between the two [70]. Therefore, value congruence between an employee and an organization is imperative for an employee to make decisions in work attitudes and behaviors [70,71]. In our study, a theoretical explanation is that employees receive information about CSR, leading to their judgment of value congruence between them and their organization, which turns into their perceived PO fit. MLT suggests that leaders use motivating language to provide clear guidance, emotional support, and meaningfulness for employee CSR engagement, which could form the basis of PO fit. Therefore, this study proposes a positive link between leader motivating language related to CSR and PO fit:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Leader motivating language in CSR is positively associated with PO fit.

Previous research has suggested positive effects of PO fit on employees’ relationships with the organization, including organizational commitment and satisfaction [26,72] as well as trust in top management [25]. A value-congruent organization could enhance employees’ favorable attitudes toward the organization [73]. PO fit has also been found to express positive relationships with employee behavioral outcomes, including job performance [24], organizational citizenship behavior [26], and employee CSR engagement [15]. Nejati et al. (2020) surveyed 142 employees in Malaysia and found that a higher PO fit led to better employee CSR engagement [15]. When employees believe their values are congruent with an organization’s values and goals, they feel more engaged with the organization [24]. Based on previous literature, this study proposed the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

PO fit is positively associated with employees’ CSR engagement.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

PO fit is positively associated with EORs.

2.6. Mediating Role of PO fit

An important element of the integrative framework of the relationship between leader motivating language in employee outcomes is that it considers a mediating mechanism to explain the effects. Leader motivating language in CSR can reinforce employees’ values and beliefs of CSR promoted by the organization, which can enhance the PO fit. Such a fit can subsequently motivate employees to engage in CSR activities and foster a high-quality relationship with the organization. The underlying mechanism can be explained by the self-fulfilling prophecy [74,75] since CSR culture informed by leaders and shared values of employees enhance connection with the organization. This study, therefore, proposes the following hypothesis (see Figure 1):

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

PO fit mediates the effect of leader motivating language in CSR on employee CSR engagement.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

PO fit mediates the effect of leader motivating language in CSR on EORs.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model.

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

To test the hypotheses, an online Qualtrics survey hosted on Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) was administered between 13 November and 15 November 2020. Participants with full-time and part-time jobs were randomly recruited. Participants who completed the survey (N = 548) received $1.60 monetary incentive. MTurk has been widely used to recruit national samples across varying demographic variables (e.g., educational background, ethnicity, gender, and income) [76]. The researchers then reviewed and excluded some data points because of incorrect answers for attention checks, insufficient completion time, and duplicated responses. Specifically, we removed 46 responses for duplications, 79 responses for failing any of the attention checks, and 17 responses for insufficient survey completion time (less than 300 s) (M = 917.58, SD = 925.11). Finally, data from 406 participants were used for analysis.

3.2. Measurement

This study adopted 12 items from J. Mayfield and Mayfield (2007) to measure leader motivating language, including direction-giving language (M = 3.2, SD = 1.2, Cronbach’s α = 0.92), empathetic language (M = 3.4, SD = 1.6, Cronbach’s α = 0.90), and meaning-making language (M = 2.8, SD = 1.4, Cronbach’s α = 0.93) [41]. Sample items are, “My boss/manager gives me clear instructions about solving CSR participation related problems” (direction-giving language), “My boss/manager expresses his/her support for my CSR participation” (empathetic language), and “My boss/manager offers me advice about how to behave at the organization’s CSR events” (meaning-making language). Following J. Mayfield and Mayfield (2007), this construct was originally measured on a 5-likert scale [41]. Then, we converted it to a 7-likert scale to align with our other constructs for data analysis convenience. Eight items were used from the scale from Rich et al. (2010) to measure employees’ CSR engagement, including emotional CSR engagement (M = 5.2, SD = 1.4, Cronbach’s α = 0.93), cognitive CSR engagement (M = 5.3, SD = 1.4, Cronbach’s α = 0.93), and behavioral CSR engagement (M = 4.9, SD = 1.7, Cronbach’s α = 0.93) [77]. Sample items are, “I am excited about my organization’s CSR activities’’ (emotional CSR engagement), “My mind will be focused when I am involved in my company’s CSR activities” (cognitive CSR engagement), and “I will actively participate in CSR activities at my company in the next 12 months” (behavioral CSR engagement). To measure PO fit, four items (M = 5.0, SD = 1.5, Cronbach’s α = 0.96) were employed from Cable and DeRue (2002) [24]. A sample item is “My personal values match my organization’s values and culture.” Eight items were adopted from Hon and Grunig (1999) to measure EORs, including three dimensions: trust (M = 4.8, SD = 1.5, Cronbach’s α = 0.9), satisfaction (M = 5.4, SD = 1.3, Cronbach’s α = 0.84), and commitment (M = 5.1, SD = 1.4, Cronbach’s α = 0.91) [63]. Sample items are, “My employer can be relied on to keep its promises” (trust), “I am happy with my employer” (satisfaction), and “I can see that my employer wants to maintain a relationship with me” (commitment). Correlations between the observed variables in this study were displayed in Table 1, ranging from 0.46 to 0.84.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics (Cronbach’s alpha, mean, standard deviation, correlations).

3.3. Analysis

To examine direct (H1–H3) and indirect effects (H4), a two-step structural equation modeling (SEM) technique was employed with the lavaan R package. The first step was a measurement model with all key variables, among which leader motivating language, employees’ CSR engagement, and EORs are second-order variables. The second step was to use a structural model to test all hypotheses. Using cross-sectional data is a common data collection approach in CSR communication research [28,78,79]. However, there is the potential issue of common method bias for cross-sectional data [80]. We addressed this issue through multiple approaches. First, following the previous research’s guidelines [81], the authors placed the independent and dependent variables in different sections in the questionnaire, and employed well-established measures from existing studies. In addition, to detect the common method bias issue, we compared the current CFA model (CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.06 (90% CI: 0.05–0.06); SRMR = 0.04; χ2 = 1059.83 ***; df = 449, χ2/df = 2.36; n = 406) with a one-factor CFA model (CFI = 0.58; TLI = 0.55; RMSEA = 0.19 (90% CI: 0.18–0.19); SRMR = 0.12; χ2 = 6902.739 ***; df = 464, χ2/df = 14.87; n = 406). The model fit in our current study was much better than the one-factor model fit. In addition, we compared the chi-square of the unconstrained model (χ2 = 1059.83, df = 449) and the chi-square of the fully constrained model (χ2 = 2307.5, df = 489). The results showed that the difference between these two models was significant (χ2 = 1247.7, df = 40, p < 0.001). Therefore, the common method bias issue was taken care of in our dataset.

4. Results

4.1. Tests on Socio-Demographic Variables

Prior to testing the proposed model, a series of linear regression analyses were conducted to investigate how relevant demographic variables (i.e., gender, management level, and organizational size) could affect the measured relationships in the SEM model. Results suggested that the management level (βnon-management = 0.55, p < 0.05) was a significant predictor for leader motivating language in CSR (βnon-management = 0.55, p < 0.05), and gender for CSR engagement (βfemale = 0.41, p < 0.01) and PO fit (βfemale = 0.41, p < 0.01). Based on the results, we controlled for the management level and gender in the SEM model for hypothesis testing.

4.2. The Measurement Model Fit

Following the guidelines of two-step SEM analysis [82], the first step in this study was a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the measurement model using the lavaan package in R. CFA suggested leader motivating language in CSR, employee CSR engagement, and EORs formed as second-order constructs with their corresponding first-order factors. The test of the measurement model indicated good data–model fit (CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.06 (90% CI: 0.05–0.06); SRMR = 0.04; χ2 = 1059.83 ***; df = 449, χ2/df = 2.36; n = 406). Table 2 displays the standardized loadings of each construct.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results.

4.3. Structural Model Results

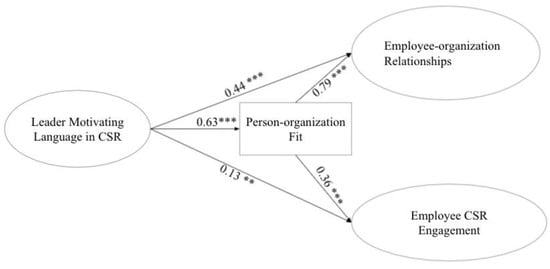

The hypothesized structural model (Figure 2) showed good fit to our data: CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.05 (90% C.I.: 0.05–0.06); SRMR = 0.07; χ2 = 1299.17 ***; df = 604, χ2/df = 2.15; n = 406. Standardized path coefficients were presented in Figure 2. To identify the best fitting model, two other theoretically plausible models were compared with our hypothesized model. To highlight the mediator of PO fit, in our alternative Model 1, the link between leader motivating language and EORs was removed. In our alternative Model 2, both links between leader motivating language and EORs and that between leader motivating language and employee CSR engagement were removed. As displayed in Table 3, the χ2 differences of the two alternative models ranged from 10.9 to 72.23 (both with p < 0.01) and supported the superiority of our hypothesized model. Given the model fit indices, the hypothesized model was kept and used for further analysis.

Table 3.

Fit indices of the hypothesized model and alternative models.

Table 3.

Fit indices of the hypothesized model and alternative models.

| Models | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fit Indices | Hypothesized Model | Alternative Model 1 | Alternative Model 2 |

| χ2 | 1299.17 | 1310.07 | 1371.39 |

| df | 604 | 605 | 606 |

| χ2/df | 2.15 | 2.17 | 2.26 |

| Δ χ2 | — | 10.90 | 72.23 |

| Sig. of Δ | — | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| CFI | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| RMSEA | 0.05 (90% CI = [0.05:0.06]) | 0.05 (90% CI = [0.05:0.06]) | 0.06 (90% CI = [0.05:0.06]) |

| SRMR | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

Note. CFI = Comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; CI = confidence interval.

Figure 2.

Estimated standardized effects in the structural modeling equation. CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.05 (CI: 0.05–0.06); SRMR = 0.07; χ2 = 1299.17 ***; df = 604, χ2/df = 2.15; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

4.4. Hypotheses Testing (Direct and Indirect Effects)

Leader motivating language in CSR demonstrated a positive effect on employee CSR engagement (β = 0.44, p < 0.001) (Table 4). This indicated that employees who felt motivated by leaders’ language in CSR were more likely to engage with CSR activities, supporting H1a. In addition, employees who identify with leaders’ use of motivating language in CSR are more likely to foster positive relationships with the organization (β = 0.13, p < 0.01). Therefore, H1b was supported. Employees reported greater PO fit when leaders employed motivating language in CSR (β = 0.63, p < 0.001), supporting H2. In addition, employees’ perceived PO fit was positively associated with EORs (β = 0.79, p < 0.001) and employees’ CSR engagement (β = 0.36, p < 0.001), supporting H3a and H3b.

Table 4.

Results of direct effects and indirect effects.

A test of mediation effects with a bootstrapping procedure (N = 5000 samples) was employed to test H5. Results revealed a significant indirect effect of leader motivating language in CSR on employee CSR engagement via PO fit (β = 0.22, 90% CI: [0.18:0.47], p < 0.001), supporting H4a. Similarly, we found a significant indirect effect of leader motivating language in CSR on EORs via PO fit (β = 0.50, p < 0.001, 90% CI: [0.82:1.46]), supporting H4b. PO fit partially explained the positive effect of leader motivating language on the quality of relationships between employees and organizations, and employee CSR engagement. We also contrasted those two indirect effects and found that the motivating language in CSR’s indirect effect on EORs was more salient than its indirect effect on employee CSR engagement (β = 0.28, p < 0.001). Thus, PO fit was a stronger mediator in the relationship between leaders’ CSR motivating language and EOR as compared to employee CSR engagement.

4.5. Additional Analyses on the Effects of Each MLT Dimension

Given the significant effect of leader motivating language on employee outcomes, we also conducted three separate path analyses to examine how each dimension of leader motivating language (i.e., direction-giving language, empathetic language, and meaning-making language) was associated with employee CSR engagement and EORs. Results (see Table 5 for coefficients) showed that each dimension of leader motivating language had a significant positive effect on cultivating employees’ PO fit, engaging employees in CSR development, and developing quality EORs.

Table 5.

Direct effects and mediation effects of leader motivating language factors.

5. Discussion

Rooted in the conceptual framework of motivating language, the present study examined leaders’ oral communication in CSR and its connection with employees’ CSR engagement and relationships with the organization. This study advances the theory via contextualizing MLT dimensions of direction-giving, empathetic, and meaning-making languages to CSR-related initiatives. Overall, our conceptual model was fully supported by an online survey among employees (N = 406), showing that leader motivating language in CSR is significantly associated with the short-term outcome of employees’ engagement and the long-term relational outcome with the organization, and that such effects are explained by a significant underlying mechanism, PO fit.

First, this study found that leader motivating language in CSR was conducive to employees’ CSR engagement. Our finding indicates that leaders’ task-related (i.e., direction-giving) and relational (i.e., empathetic and meaning-making) languages are pertinent to maximizing employees’ motivations to engage CSR at emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions. As a result, employees will be more proactive to emotionally attach with, cognitively perceive, and behaviorally participate in their organization’s CSR initiatives with a high level of leader motivating language in CSR. Our finding confirms the effectiveness of leader–subordinate oral communication on employees’ engagement [28], and the current study is among the first to explain such a positive association in the CSR context. Since transparency is the cornerstone in driving engagement [83], leaders’ direction-giving language in clarifying ambiguities improves transparency in information, goal attainment, and procedure in CSR engagement, which ultimately make employees aware of what they are expected to achieve and benefit from engaging in their company’s CSR initiatives. Simply asking an employee to engage in CSR can be overwhelming, but asking someone to help develop a specific CSR policy or a CSR activity could generate better outcomes. In addition, once employees know the benefits of CSR engagement, such as emotional benefits (e.g., pride and pleasure) and functional benefits (e.g., skills acquisition), they are more likely to get involved with a company’s CSR at both the cognitive and behavioral levels [9]. Empathetic language in CSR enables leaders to reinforce social connections with employees by maintaining a supportive emotional bond. Engaging in CSR involves psychological risk since employees might have to sacrifice some work and personal time [55]. Therefore, leaders’ language to show their emotional support can eliminate employees’ concerns and create emotional ties providing employees with psychological safety in engaging with CSR, leading to a gain in employees’ confidence and comfort in CSR engagement. Sometimes, employees simply do not know why they need to engage with their company’s CSR initiatives, which makes them hesitant to either emotionally and cognitively recognize the importance of the company’s CSR or participate in CSR-related activities. Leaders’ language on meaning-making not only lets employees know that their CSR engagement is valued, but it also shows them how their personal contributions tie in with larger organizational goals in CSR development, thus encouraging them to explore more CSR engagement opportunities.

Second, our study confirms that leader motivating language, especially in the CSR context, can foster the quality of EORs. Unlike CSR communication from the organization’s perspective alone, empathetic and meaning-making languages in CSR allow leaders to put employees at the center of CSR communication. By providing social connections and emotional support in communicating CSR, employees could feel more affiliated with, valued, and respected in the organization, and could drive employees to demonstrate higher levels of trust, satisfaction, and commitment towards the organization.

Third, we identified PO fit as an important psychological mechanism explaining the effects of leader motivating language in CSR. Consistent with previous literature [26,68], our findings suggest that value congruence between employees’ personal values and the organization’s values was more likely to be formed when leaders employed motivating language in CSR. Leader motivating language in CSR communicates significant information about a company’s CSR, especially how CSR is encouraged and supported among employees. Consequently, such motivating languages could factor into employees’ evaluations about how their own values and needs might be satisfied by the organization [25]. Employees could match their values and the goals with those promoted by the organization, which are communicated via leaders, enhancing employees’ PO fit. In turn, the fit subsequently encourages employees to generate both better relational outcomes and engagement outcomes with the organization as a way to enhance their value congruence and reflect their leaders’ oral communication. Situated in a CSR context, these findings extend the literature on PO fit as a significant mediator between internal CSR communication and employee outcomes [25].

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

The findings of this study provide both theoretical and practical contributions to internal CSR communication in the realms of public relations and management. Theoretically, first, by demonstrating positive associations between leader motivating language and employee outcomes, this study suggested MLT as an effective conceptual construct in internal CSR communication research. Understanding the role and impact of leader motivating language in the context of internal CSR communication advances the theoretical development of CSR communication. Unlike Morsing and Schultz’s typology (2006) emphasizing interactivity in CSR communication with stakeholders [84], and Kim’s (2019) typology focusing on the utility and effectiveness of organizational CSR communication strategies, we argue that leaders’ rhetorical skills are key in CSR communication [79]. By examining leaders’ ML impacts, this study links CSR communication research to internal communication, answering scholarly calls for more internal CSR research [28].

Second, as researchers in MLT have noted the necessity of contextualizing its theory [23], our study advances MLT by focusing on CSR. CSR is the best approach to humanize a company [85], and leaders’ language use in clarifying, emotionally supporting, and valuing employees’ CSR can enhance the irreplaceable role of employees in a company’s overall CSR development. This study advances MLT by examining its impact on employees’ CSR engagement rather than work engagement or job performance [22,37]. Thus, our empirical evidence provides valuable insights into MLT’s impacts in the context of CSR, which helps develop specific strategies for internal CSR promotion.

Third, given the call for understanding the mediating mechanism to explain through which motivating language operates [23], this study extends the literature by adding PO fit. Leader motivating language in CSR builds employees’ relevant values and goals, which, in turn, fosters high-quality EORs and enhances employee CSR engagement. This study contributes to internal communication literature by adding PO fit as an effective mediator. Although PO fit has been widely used as a mechanism to explain the relationships between employees’ perceptions and their attitudinal and behavioral performances in the management literature [26,72], little is known about its role in internal CSR engagement. By examining the mediating effects of PO fit, we are able to explain the underlying psychological mechanism driving employees’ CSR engagement and relationship with the employer.

This study also has practical implications for CSR communication. First, this study provides guidance for leaders on how to take advantage of their language use in motivating employees in CSR engagement and maintaining quality relationships with employees. Based on the positive effects of ML found in our study, we provide three recommendations for managers to foster internal CSR engagement and build positive relationships with employees. For example, managers may use more direction-giving language in CSR communication by providing clear directions to CSR participations and articulating the benefits that employees can gain through CSR participations.

Second, recognizing the significant effects of leader MLT in internal CSR promotion, leadership training programs should emphasize speech and oral communication skills more. Managers can also employ empathetic language by encouraging employees to share their stories about CSR engagement and by showing emotional support to employees’ CSR engagement. Adopting the meaning-making language, leaders should consider adding CSR into their company’s vision and long-term objectives and work together with HR departments and employees to co-create an internal CSR culture, which enhances employees’ sense-making of CSR through normative CSR engagement.

Third, given the mediating role of PO fit, companies should regularly promote the company’s values and goals in CSR development in leadership and employee training. In this way, employees’ congruent values can be invoked to assess when they are stimulated by leaders’ languages in CSR.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the contributions, this study encountered several limitations. First, the sample was obtained in MTurk, which might not properly represent the overall larger U.S. population [86]. Therefore, findings of this study should be interpreted with caution due to a lack of generalizability. Future research should recruit more representative and diverse sample groups to explore how leader motivating language operates. Second, this study did not examine the link between employee CSR engagement and EORs. Based on the role of reciprocity [87,88], individuals who have trust in, feel satisfied with, and have a mutual commitment to the organization are more likely to be motivated to have better CSR engagement. Thus, future research could examine how engagement and relationships are related when employing leader motivating language as an antecedent. Finally, this study did not include moderators. Future research may consider individual factors, such as employees’ positive emotions, employees’ felt obligation, perceived CSR importance, and issue relevance, as potential moderators influencing the relationship between leader motivating language and employees’ CSR engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and C.D.; Methodology, Y.Z. and C.D.; Formal analysis, Y.Z.; Writing-original draft, Y.Z., C.D. and A.M.M.W.; Writing-review & editing, Y.Z., C.D., A.M.M.W. and S.H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the 2019 Killgore Faculty Grant at West Texas A&M University, Canyon, TX, USA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of West Texas A&M University (30 January 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cone. CRS/Cone 2008 Corporate Responsibility in a New World Survey Fact Sheet, 2008. Cone Homepage. Available online: https://www.conecomm.com/2008-cone-communicationsbsr-corporate-responsibility-in-a-new-world-survey-pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Deloitte. Corporate Social Responsibility Report, 2016. Deloitte Homepage. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ie/Documents/aboutdeloitte/IE_CR%20Report_FY2016_September.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- PricewaterhouseCoopers, P.W.C. Millennials at Work. Reshaping the Workplace, 2011. P.W.C. Homepage. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/co/es/publicaciones/assets/millennials-at-work.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Mamantov, C. The engine behind employee communication. Commun. World 2009, 26, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M. Employee participation in CSR and corporate identity: Insights from a disaster-response program in the Asia-Pacific. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2009, 12, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L.N. Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.; Akremi, A.E.; Swaen, V. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, S.; Bogel, P.M.; Adam, U. Employees’ perceived benefits from participating in CSR activities and implications for increasing employees engagement in CSR. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2019, 24, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanesh, G.S. CSR as organization–employee relationship management strategy: A case study of socially responsible information technology companies in India. Manag. Commun. Q. 2014, 28, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, B.; Hillenbrand, C.; Money, K. Building employee relationships through CSR: The moderating impact of cynicism and reward for application. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 295–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, M.; Simonsson, C. Coworkership and engaged communicators. In Handbook of Communication Engagement; Johnston, K.A., Taylor, M., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Yue, C.A. Status of internal communication research in public relations: An analysis of published articles in nine scholarly journals from 1970 to 2019. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.R.; Huang-Baesecke, C.F. Examining the internal aspect of corporate social responsibility (CSR): Leader behavior and employee CSR participation. Commun. Res. Rep. 2014, 31, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Kong Loke, C. Can ethical leaders drive employees’ CSR engagement? Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 16, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, B.; Guo, Y. Affective and cognitive trust as mediators in the influence of leader motivating language on personal initiative. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2020, 58, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, M.; Mayfield, J. Leader talk and the creative spark: A research note on how leader motivating language use influences follower creative environment perceptions. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2017, 54, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledow, R.; Frese, M. A situational judgment test of personal initiative and its relationship to performance. Pers. Psychol. 2009, 62, 229–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, J.R.; Searle, J.R. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1969; Volume 626. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield, J.; Mayfield, M. The relationship between leader motivating language and self-efficacy: A partial least squares model analysis. J. Bus. Commun. 2012, 49, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, M.; Mayfield, J.; Walker, R. Leader communication and follower identity: How leader motivating language shapes organizational identification through cultural knowledge and fit. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2021, 58, 221–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.T.; Parker, M.A. Communication: Empirically testing behavioral integrity and credibility as antecedents for the effective implementation of motivating language. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2017, 54, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, J.; Mayfield, M. Motivating Language Theory: Effective Leader Talk in the Workplace; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donia, M.B.L.; Ronen, S.; Tetrault Sirsly, C.; Bonaccio, S. CSR by any other name? The differential impact of substantive and symbolic CSR attributions on employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Aryee, S.; Loi, R.; Kim, S. Person-organization fit and employee outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 3719–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthler, G.; Dhanesh, G.S. The role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and internal CST communication in predicting employee engagement: Perspectives from the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, Y. Driving employee engagement through CSR communication and employee perceived motives: The role of CSR-related social media engagement and job engagement. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2020, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Cheema, S.; Javed, F. Activating employee’s pro-environmental behaviors: The role of CSR, organization identification, and environmentally specific servant leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.J. Three roles of language in motivation theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, J.; Mayfield, M. Learning the language of leadership: A proposed agenda for leader training. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 1995, 2, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, J.; Mayfield, M. The role of leader motivating language in employee absenteeism. J. Bus. Commun. 2009, 46, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Organizational Behavior, 12th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G.A. Leadership in Organizations, 8th ed.; Pearson: Albany, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Madlock, P.E.; Sexton, S. An application of motivating language theory in Mexican organizations. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2015, 52, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlock, P.E. The influence of motivational language in the technologically mediated realm of telecommuters. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2013, 23, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, M.; Mayfield, J. The effects of leader motivating language use on employee decision making. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2016, 53, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, J.A. Motivating Language Theory: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Ph.D. Thesis, The State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield, J.; Mayfield, M. The effects of leader communication on a worker’s intent to stay. An investigation using structural equation modeling. Hum. Perform. 2007, 20, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.T. The Motivating Language of Principals: A Sequential Transformative Strategy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, S.L. Employee engagement: 10 key questions for research and practice. In Handbook of Employee Engagement: Perspectives, Issues, Research and Practice; Albrecht, S.L., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Utrecht work engagement scale: Preliminary manual. Occup. Health Psychol. Unit Utrecht 2003, 26, 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Soane, E.; Truss, C.; Alfes, K.; Shantz, A.; Rees, C.; Gatenby, M. Development and application of a new measure of employee engagement: The ISA Engagement Scale. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2012, 15, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.Y.; Zhang, W.; Abitbol, A. What makes CSR communication lead to CSR participation? Testing the mediating effects of CSR associations, CSR credibility, and organization-public relationships. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, B.; Ihlen, O. Corporate social responsibility and engagement. In Handbook of Communication Engagement; Johnston, K.A., Taylor, M., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Sung, M. How symmetrical employee communication leads to employee engagement and positive employee communication behaviors: The mediation of employee-organization relationships. J. Commun. Manag. 2017, 21, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Jiang, H. Cultivating quality employee-organization relationships: The interplay among organizational leadership, culture, and communication. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2016, 10, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, M.; Jackson, P. Rethinking internal communication: A stakeholder approach. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2007, 12, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rabiul, M.K.; Yean, T.F. Leadership styles, motivating language, and work engagement: An empirical investigation of the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, J.B. Finding meaning through volunteering: Why do employees volunteer and what does it mean for their jobs? Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1274–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brieger, S.A.; Anderer, S.; Frohligh, A.; Baro, A.; Meynhardt, T. Too much of a good thing? On the relationship between CSR and employee work addiction. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kent, M.; Taylor, M. Toward a dialogic theory of public relations. Public Relat. Rev. 2002, 28, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-H. Public relations strategies and organization–public relationships. In Proceedings of the annual conference of the Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication, Baltimore, MD, USA, 5–8 August 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ledingham, J.A. Relationship management: A general theory of public relations. In Public Relations As Relationship Management: A Relationship Approach to the Study and Practice of Public Relations; Ledingham, J.A., Bruning, S.D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2006; pp. 412–477. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, B. Employee/Organizational Communications, 2008. Institute for Public Relations Homepage. Available online: http://www.instituteforpr.org/topics/employeeorganizational-communications/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Men, L.R.; Stacks, D. The effects of authentic leadership on strategic internal communication and employee-organization relationships. J. Public Relat. Res. 2014, 26, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, R. Corporate Reputation and the Bottom Line: Powerful, Proven Communication Strategies for Maximizing Value, 2005. The Chartered Institute of Marketing Homepage. Available online: http://www.untagsmd.ac.id/files/Perpustakaan_Digital_1/BRAND%20NAME%20PRODUCTS%20Corporate%20Reputation,%20the%20Brand%20&%20the%20Bottom%20Line%20-%20Powerful,%20Proven%20Communic.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Men, L.R.; Sung, Y. Shaping corporate character through symmetrical communication: The effects of employee-organization relationships. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2019, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, L.; Grunig, J.E. Guidelines for Measuring Relationships in Public Relations; Commission on PR Measurement and Evaluation; The Institute for Public Relations: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-N.; Rhee, Y. Strategic thinking about employee communication behavior (ECB) in public relations: Testing the models of megaphoning and scouting effects in Korea. J. Public Relat. Res. 2011, 23, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G.R. Journalists’ evaluation of corporate reputations. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2004, 7, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlock, P.E. The link between leadership style, communicator competence, and employee satisfaction. J. Bus. Commun. 2008, 45, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mikkelson, A.C.; Sloan, D.; Hesse, C. Relational communication messages and leadership styles in supervisor/employee relationships. Int. J. Bus. Ommunication 2019, 56, 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauver, K.; Kristof-Brown, A. Distinguishing between employee’s perceptions of person-job and person-organization fit. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 59, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, M.J. Person-organization fit. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroff, C.; Shin, Y.; Kinicki, A.J. Multiple perspectives of congruence: Relationships between value congruence and employee attitudes. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 591–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verquer, M.L.; Beehr, T.A.; Wagner, S.H. A meta-analysis of the relationship between person-organization fit and work attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, W.; Bell, S.T.; Villado, A.J.; Doverspike, D. The use of person-organization fit in employment decision making: An assessment of its criterion-related validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 786–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patricia Duarte, A.; Mouro, C.; Goncalves das Neves, J. Corporate social responsibility: Mapping its social meaning. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2010, 8, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, P.; Arenas, D. Do employees care about CSR programs? A typology of employees according to their attributes. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.; Irani, L.; Silberman, M.S.; Zaldivar, A.; Tomlinson, B. Who are the crowdworkers? Shifting demographics in Mechanical Turk. Extended Abstracts in Hum. Factors Comput. Syst. 2010, 2863–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.C.; Chen, H.T.; Gan, C. Consumers’ engagement with corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication in social media: Evidence from China and the United States. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The process model of corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication: CSR communication and its relationship with consumers’ CSR knowledge, trust, and corporate reputation perception. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.M.; Lance, C.E. What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, Y.C.; Egri, C.P.; Lin, C.Y.Y. Do corporate social responsibility practices yield different business benefits in eastern and western contexts? Chin. Manag. Stud. 2014, 8, 556–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wayne, J.H.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Work–family facilitation: A theoretical explanation and model of primary antecedents and consequences. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M. Corporate social responsibility communication: Stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Bus. Ethics: A Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S.; Korschum, D. Using Corporate Social Responsibility to Win the War for Talent, 2008. MIT Sloan Management Review Homepage. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/using-corporate-social-responsibility-to-win-the-war-for-talent/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Shen, H.; Jiang, H. Engaged at work? An employee model in public relations. J. Public Relat. Res. 2019, 31, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, S.; Holmes, N. The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2006, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hayes, T.L. Business-unit level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).