Evaluating Attitudes towards Large Carnivores within the Great Bear Rainforest

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

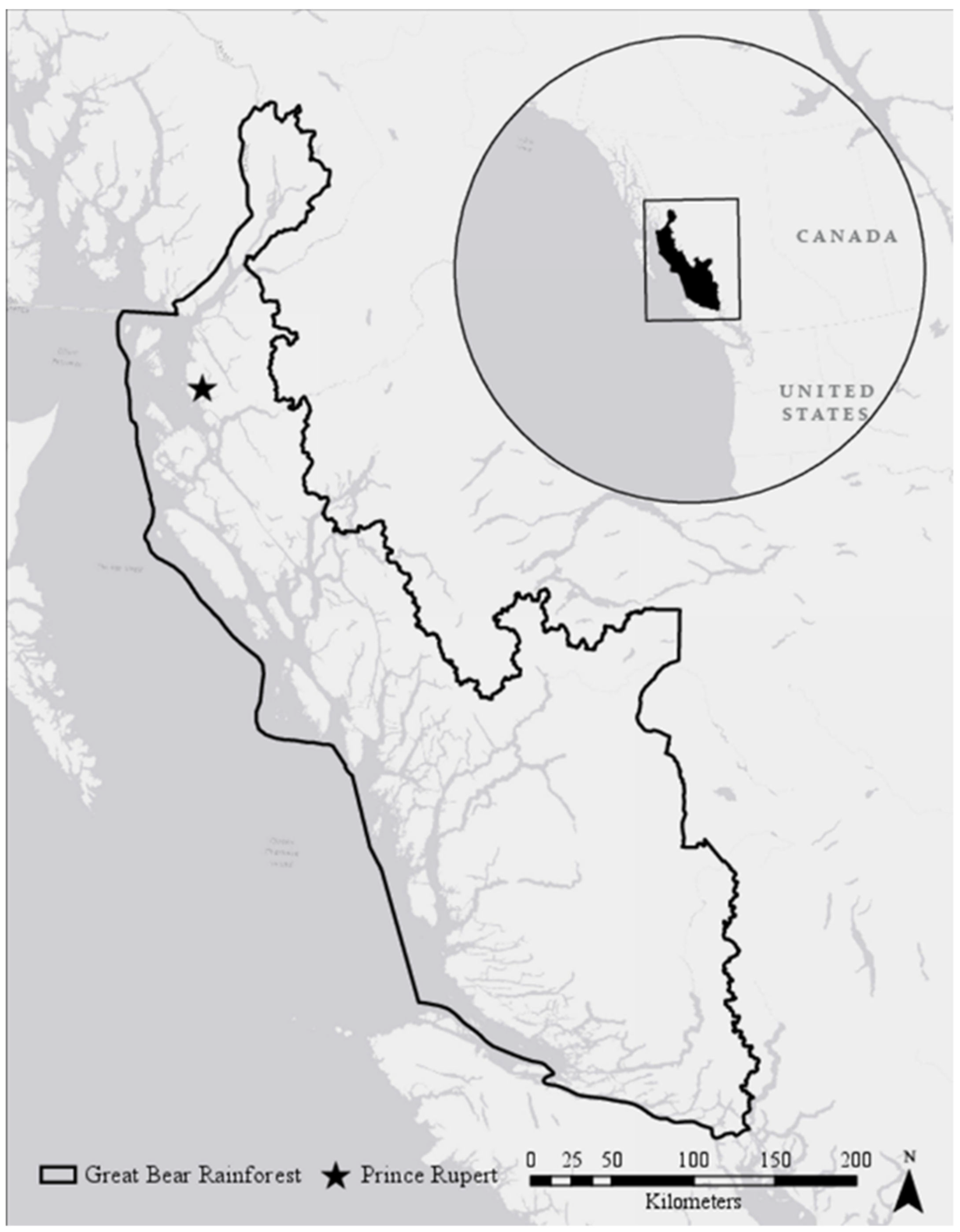

2.1. Study Area: The Great Bear Rainforest

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Thematic Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Survey Respondents

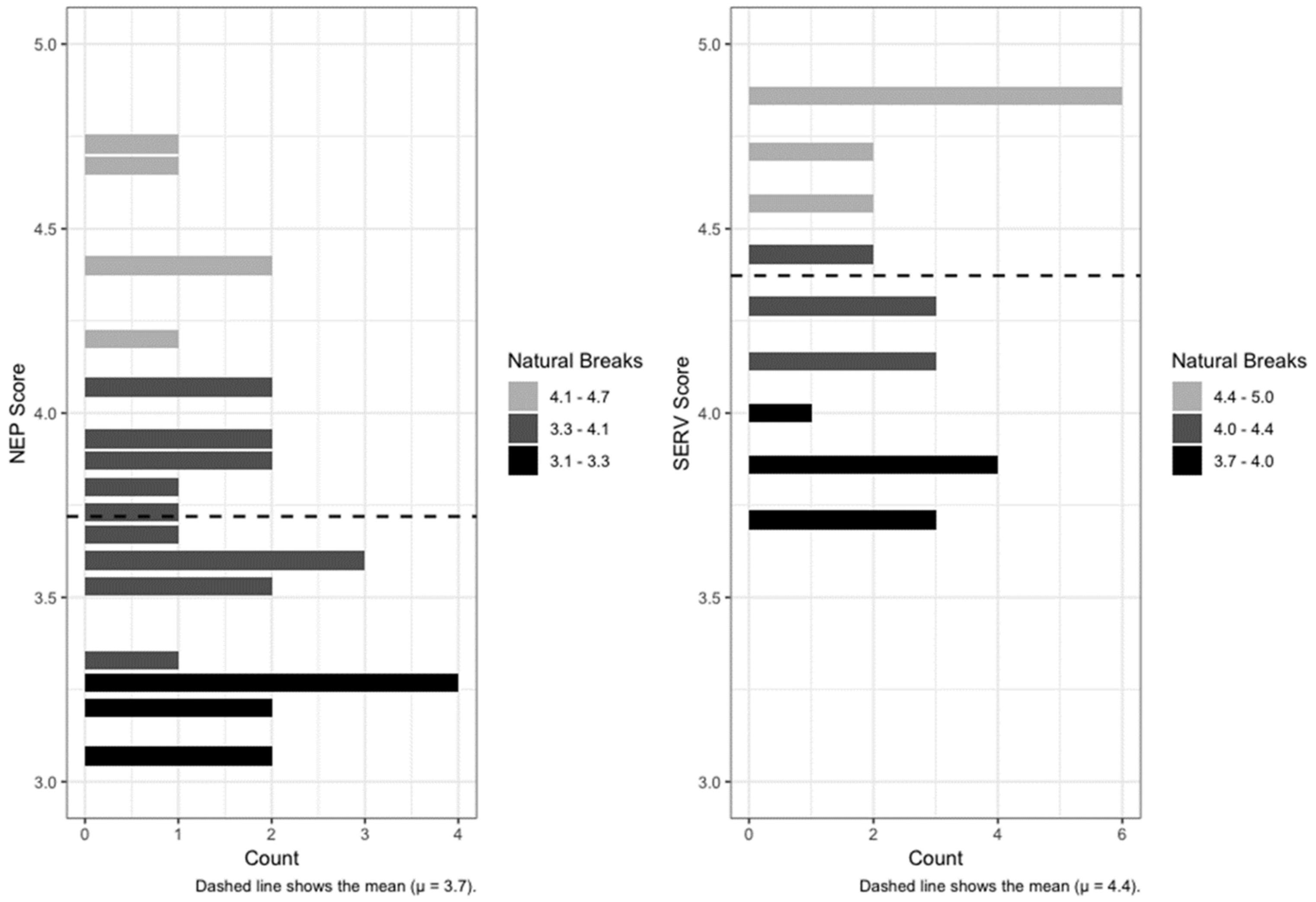

3.2. NEP and SERV Results

3.3. Results of Thematic Analysis of Feelings and Attitudes Surrounding Carnivores

I thought that [the wolf] was so majestic. It was so… to me, it was miraculous. It’s like, that doesn’t happen. I felt so lucky.[Respondent 8576]

The experiences with animals here are generally… it’s by the side of the road.

Yeah, it’s always nice to see them on the side of the road, wouldn’t want to see one if I was on a bike or walking though, in the safety of a car.[Respondent 5363]

I’ve luckily been in a car every single time.[Respondent 5496]

All positive. Yeah, it was usually in the vehicle driving and seeing them on the road. So… yeah.[Respondent 7190]

I was in a car, so it was you know I felt safe enough that I could just safely enjoy the experience.[Respondent 4031]

The wolf is negative because he’s in town. […] he’s too close to my house. […] But no, when you see it on the highway, it’s their environment. They should be there.[Respondent 2992]

How much more destructive the human race is to those environments compared to the animals that actually have lived in those environments and thrived for many, many years. [Respondent 2713]

To the native people here, they have real spiritual value. There’s their beliefs that go along with them, and they represent concepts, they represent stories, they represent the gods, and culturally they’re important as a food source and fur source and things like that.[Respondent 7887]

Most of the people who are indigenous to this area have a tribe that’s associated with a large animal, so the bear clan is a clan of many of the First Nations around here. My partner […] he’s a wolf. So, there’s quite a bit of cultural importance to the different mammals here. And people have kind of a reverence for them. And even if they hunt them, they’ll, you know, usually say a few words or have some kind of spiritual connection with the animal and do some kind of right to go along with that process.[Respondent 3739]

| Quote | Respondent |

|---|---|

| [First Nations are] deeply tied to the culture in the area. | 2331 |

| I’ve gotten to learn a lot more about First Nations culture since moving here. And that was actually one of the draws for me that, you know, one of the many obviously but didn’t hinge my move on… on that, but it was, it was definitely a highlight of it. And so, from what I’ve learned in meeting other people and getting to understand the various tribes, there are so many, like, all the animals are really culturally important from the Great Bear to the small frog and of course, the eagle and Raven and… and so they’re yeah, they’re all important and revered. | 2656 |

| There’s a white spirit bear that holds a cultural significance for my first nations friends, but being a white Caucasian, I haven’t adopted that route spirituality with them, but I enjoy watching them and am amazed on how they survive and their animal instincts. | 4860 |

| A few my friends are first nation, and seem to have a very high regard for all the animals, actually so yeah. | 5270 |

| Well, to the First Nations and Prince Rupert, absolutely. Like the wolf, the bear, the Eagles, like they’re majestic, like for myself, I grew up with the, you know, with these animals all around, and I have nothing but respect for them. So, the wolves are a little bit newer, when you see a wolf going around town like he owns the joint, but like I said, I’m just partial to wolves, but it… it’s I think they all serve, you know, they’re all here for a reason. And then spiritually, we should respect that. | 5279 |

| I mean, all the species are very culturally and spiritually important to the local First Nations. You know, they have lots of stories and songs and artwork that depict the wildlife and as well as people like me, white, Caucasian, you know, they’re important to me. It’s nice to be able to have this wildlife in our backyard. | 9756 |

3.4. Results of Thematic Analysis of Conservation Related Ideas

I don’t really believe trophy hunting is necessary, it contributes somewhat to the economy, but again, we should probably be more focused on ecotourism opportunities, especially considering sometimes, I’m stereotyping a little bit honestly, but the type of people who come in to do trophy hunting are generally flying into one specific area, they’re hiring one tour guide operator, and they’re not necessarily traveling to the surrounding community. So, there’s not exactly that much benefit.[Respondent 3739]

I would… trophy no. There’s maybe in other places but like I said I see more value in shooting the animals with a camera… you can do that multiple times and the economic driver off of that is way more valuable.[Respondent 4532]

Only sustenance hunting, sustenance hunting, one bear can feed a very large family or last for many years. Trophy hunting really, they take either the claws or the face of the animal and they leave the rest to rot.[Respondent 5416]

I would be concerned if [First Nations] don’t have regulations, can they potentially overhunt that species?[Respondent 6247]

The Aboriginal food hunting and food fishing, and I think they should be managed closer, maybe not internally, but externally.[Respondent 7190]

And there are a lot of non-native people that will bring a First Nations companion along so that they’re able to hunt, really.[Respondent 5146]

First Nations people want to have their own identity, but yet they constantly divide themselves against the white—It’s either the white people or the First Nations and so I would like it to be all people because it discredits the people that love the world, love outdoors just as much as First Nations people do.[Respondent 4860]

I have mixed opinions on segregating people because of their heritage, or their nationality. Or, you know, First Nations or like I, you know, I’m Canadian, I’m born and raised here. I’m not allowed to go out and fish salmon on the river. But the first nations are allowed to put a net across the entire river and fish as much salmon as they want. And they’re worried about the salmon stocks. But I think it’s in our Constitution that we cannot limit First Nations whether it’s hunting or fishing or anything, so really they have free game at pretty much whatever they want, unless it’s an endangered species. […] And what, you know, it’s just my opinion on it. But it’s not their fault. It’s the governments that are creating these rules.[Respondent 9756]

4. Discussion

4.1. Ecological Beliefs in Prince Rupert Tend to Range from Neutral to Ecocentric and Are Likely Influenced by a Strong Sense of Place

I think Canadians think about the wilderness and wild animals as part of our national psyche, especially of people who live up in the northern parts of the country.[Respondent 7887]

We’re in a special spot here.[Respondent 9756]

It’s really, it’s really special and I’m glad that we’ve protected it from the get go.[Respondent 2656]

4.2. First Nations and Non-First Nations Prince Rupert Residents Exhibit Similar Pro-Ecological Worldviews

4.3. The Attitudes towards Large Mammalian Carnivores in Prince Rupert Are Strongly Positive but Depend on Where the Encounter Occurs

4.4. Considerations for Creating Inclusive Environmental and Carnivore Management Plans

4.5. Limitations and Next Steps

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Distribution Statement A

Disclaimer

References

- Hausmann, A.; Slotow, R.; Burns, J.K.; Minin, E.D. The ecosystem service of sense of place: Benefits for human well-being and biodiversity conservation. Environ. Conserv. 2016, 43, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dietz, T. Drivers of Human Stress on the Environment in the Twenty-First Century. Annu. Rev. Environ. 2017, 42, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D. Causes, consequences and ethics of biodiversity. Nature 2000, 405, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.; Ngo, H.T.; Guèze, M.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.; Butchart, S.; et al. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Zenodo: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Mooney, H.A. Extinction, Substitution, and Ecosystem Services. BioScience 1983, 33, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, M.S.; Nickerson, N.P.; Metcalf, E.C. Using Spatial, Economic, and Ecological Opinion Data to Inform Gray Wolf Conservation. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2016, 40, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ripple, W.J.; Estes, J.A.; Beschta, R.L.; Wilmers, C.C.; Ritchie, E.G.; Hebblewhite, M.; Berger, J.; Elmhagen, B.; Letnic, M.; Nelson, M.P.; et al. Status and Ecological Effects of the World’s Largest Carnivores. Science 2014, 343, 1241484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ripple, W.J.; Beschta, R.L.; Fortin, J.K.; Robbins, C.T. Trophic cascades from wolves to grizzly bears in Yellowstone. J. Anim. Ecol. 2014, 83, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Painter, L.E.; Beschta, R.L.; Larsen, E.J.; Ripple, W.J. Aspen recruitment in the Yellowstone region linked to reduced herbivory after large carnivore restoration. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Beschta, R.L. Wolf reintroduction, predation risk, and cottonwood recovery in Yellowstone National Park. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 184, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberte, A.S.; Ripple, W.J. Range Contractions of North American Carnivores and Ungulates. BioScience 2004, 54, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lute, M.; Gore, M. Knowledge and Power in Wildlife Management. J. Wildl. Manag. 2014, 78, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, S.; Macdonald, D.W. Predicting ranchers’ intention to kill jaguars: Case studies in Amazonia and Pantanal. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 147, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, J.; Sjöström, M. Human attitudes towards wolves, a matter of distance. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 137, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beschta, R.L.; Painter, L.E.; Ripple, W.J. Trophic cascades at multiple spatial scales shape recovery of young aspen in Yellowstone. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 413, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, K.S.; Dickman, A.J.; Macdonald, D.W.; Mourato, S.; Johnson, P.; Sibanda, L.; Loveridge, A. The importance of tangible and intangible factors in human–carnivore coexistence. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røskaft, E.; Händel, B.; Bjerke, T.; Kaltenborn, B.P. Human attitudes towards large carnivores in Norway. Wildl. Biol. 2007, 13, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collings, P. The cultural context of wildlife management in the Canadian North. In A Contested Arctic: Indigenous People, Industrial States, and the Circumpolar Environment; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1997; pp. 13–40. ISBN 978-0-295-80287-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cullon, D. A View from the Watchman’s Pole: Salmon, Animism and the Kwakwaka’wakw Summer Ceremonial. BC Stud. Br. Columbian Q. 2013, 177, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritts, S.; Stephenson, R.; Hayes, R.; Boitani, L. Wolves and Humans. USGS North. Prairie Wildl. Res. Cent. 2003, 317, 289–316. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D.A.; Slocombe, D.S. Respect for Grizzly Bears: An Aboriginal Approach for Co-existence and Resilience. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.; Stewart, S. Sense of Place: An Elusive Concept That is Finding a Home in Ecosystem Management. J. For. 1998, 96, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P. The Structure Of Environmental Concern: Concern For Self, Other People, And The Biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cocks, S.; Simpson, S. Anthropocentric and Ecocentric: An Application of Environmental Philosophy to Outdoor Recreation and Environmental Education. J. Exp. Educ. 2015, 38, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanos, S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.; Skordoulis, M.; Chalikias, M.; Arabatzis, G. An Application of the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) Scale in a Greek Context. Energies 2019, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klain, S.C.; Olmsted, P.; Chan, K.M.A.; Satterfield, T. Relational values resonate broadly and differently than intrinsic or instrumental values, or the New Ecological Paradigm. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Balvanera, P.; Benessaiah, K.; Chapman, M.; Díaz, S.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Gould, R.; Hannahs, N.; Jax, K.; Klain, S.; et al. Opinion: Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finn, S.; Herne, M.; Castille, D. The Value of Traditional Ecological Knowledge for the Environmental Health Sciences and Biomedical Research. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 85006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lute, M.L.; Carter, N.H.; López-Bao, J.V.; Linnell, J.D.C. Conservation professionals agree on challenges to coexisting with large carnivores but not on solutions. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 218, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.; Carpenter, J.; Housty, J.; Neasloss, D.; Paquet, P.; Service, C.; Walkus, J.; Darimont, C. Toward increased engagement between academic and indigenous community partners in ecological research. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Low, M.; Shaw, K. First Nations Rights and Environmental Governance: Lessons from the Great Bear Rainforest. BC Stud. 2012, 172, 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Riddell, D. Evolving Approaches to Conservation: Integral Ecology and Canada’s Great Bear Rainforest. World Futures 2005, 61, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheick, B.K.; McCown, W. Geographic distribution of American black bears in North America. Ursus 2014, 25, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.; Roburn, A.; MacKinnon, A. Ecosystem-based management in the Great Bear Rainforest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada G. of C. 2016 Census of Population. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/index-eng.cfm (accessed on 9 February 2018).

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New Trends in Measuring Environmental Attitudes: Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-45614-9. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.; Ma, Z.; Laudati, A.; Berger, J. Human–Carnivore Interactions: Lessons Learned from Communities in the American West. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2015, 20, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AISense. Otter Voice Notes; AISense: Los Altos, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International. NVivo Pro; QSR International: Burlington, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austira, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jenks, G. The Data Model Concept in Statistical Mapping. Int. Yearb. Cartogr. 1967, 7, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.J.D.; Goodchild, M.; Longley, P. Geospatial Analysis—A Comprehensive Guide to Principles, Techniques and Software Tools, 2nd ed.; Troubador Publishing Ltd.: Leicester, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-905-88660-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gangaas, K.E.; Kaltenborn, B.P.; Andreassen, H.P. Environmental attitudes associated with large-scale cultural differences, not local environmental conflicts. Environ. Conserv. 2015, 42, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Riper, C.J.; Kyle, G.T. Capturing multiple values of ecosystem services shaped by environmental worldviews: A spatial analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.R.; Simpson-Housley, P.; Deman, A.F. Wilderness: Rural and Urban Attitudes and Perceptions. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Is It Really Just a Social Construction?: The Contribution of the Physical Environment to Sense of Place. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartmann, F.M.; Purves, R.S. Investigating sense of place as a cultural ecosystem service in different landscapes through the lens of language. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 175, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, O.; Swain, P.; Convery, I. Bears, Place-Making, and Authenticity in British Columbia. Nat. Areas J. 2014, 34, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Semken, S.; Brandt, E. Implications of Sense of Place and Place-Based Education for Ecological Integrity and Cultural Sustainability in Diverse Places. In Cultural Studies and Environmentalism: The Confluence of EcoJustice, Place-Based (Science) Education, and Indigenous Knowledge Systems; Tippins, D.J., Mueller, M.P., van Eijck, M., Adams, J.D., Eds.; Cultural Studies of Science Education; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 287–302. ISBN 978-90-481-3929-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Bjerke, T. Associations between environmental value orientations and landscape preferences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforti, V.A.; de Azevedo, F.C.C. Local perceptions of jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor) in the Iguaçu National Park area, south Brazil. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 111, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, S.; Macdonald, D.W. Mind over matter: Perceptions behind the impact of jaguars on human livelihoods. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 224, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Lancaster, B.-L. Public Attitudes toward Black Bears (Ursus americanus) and Cougars (Puma concolor) on Vancouver Island. Soc. Anim. 2010, 18, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.; Quinn, M. Coexisting with Cougars: Public Perceptions, Attitudes, and Awareness of Cougars on the Urban-Rural Fringe of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Human Wildl. Interact. 2009, 3, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morzillo, A.T.; Mertig, A.G.; Garner, N.; Liu, J. Resident Attitudes toward Black Bears and Population Recovery in East Texas. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2007, 12, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorresteijn, I.; Hanspach, J.; Kecskés, A.; Latková, H.; Mezey, Z.; Sugár, S.; von Wehrden, H.; Fischer, J. Human-carnivore coexistence in a traditional rural landscape. Landsc. Ecol. 2014, 29, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Black, M.; Rush, C.R.; Bath, A.J. Human Culture and Large Carnivore Conservation in North America. Conserv. Biol. 1996, 10, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNay, M. Wolf-Human Interactions in Alaska and Canada: A Review of the Case History. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2002, 30, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, T.T. A Model Environmental Nation? Canada as a Case Study for Informing US Environmental Policy. Am. Rev. Can. Stud. 2011, 41, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, M. Opinion. Grizzlies in the Backyard. The New York Times, 10 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, H.; Corrigan, C.; Rubis, J.; Zanjani, L.V. Territories of Life: 2021 Report; ICCA Consortium: Genolier, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, J.-M.; Bouthillier, L.; Bulkan, J.; Nelson, H.; Trosper, R.; Wyatt, S. What does “First Nation deep roots in the forests” mean? Identification of principles and objectives for promoting forest-based development. Can. J. For. Res. 2016, 46, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Goal 15: Life On Land. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/envision2030-goal15.html (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Larson, S.; De Freitas, D.M.; Hicks, C.C. Sense of place as a determinant of people’s attitudes towards the environment: Implications for natural resources management and planning in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 117, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, M.F.; Kasworm, W.F.; Annis, K.M.; MacHutchon, A.G.; Teisberg, J.E.; Radandt, T.G.; Servheen, C. Conservation of Threatened Canada-USA Trans-border Grizzly Bears Linked to Comprehensive Conflict Reduction. Hum. Wildl. Interact. 2018, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eeden, L.M.; Bogezi, C.; Leng, D.; Marzluff, J.M.; Wirsing, A.J.; Rabotyagov, S. Public willingness to pay for gray wolf conservation that could support a rancher-led wolf-livestock coexistence program. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 260, 109226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.; Wellwood, D.; Ciarniello, L. Bear Smart Community Program: Background Report; BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marchini, S.; Macdonald, D.W. Can school children influence adults’ behavior toward jaguars? Evidence of intergenerational learning in education for conservation. Ambio 2020, 49, 912–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lute, M.L.; Carter, N.H. Are We Coexisting With Carnivores in the American West? Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Killion, A.K.; Ramirez, J.M.; Carter, N.H. Human adaptation strategies are key to cobenefits in human–wildlife systems. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.L.; Coleman, C.-L. Is the New Ecological Paradigm Scale Stuck in Time? A Working Paper. In Proceedings of the Iowa State University Summer Symposium on Science Communication; Iowa State University, Digital Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2014; p. 12298912. [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde, R.; Jackson, E.L. The New Environmental Paradigm Scale: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness? J. Environ. Educ. 2002, 33, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawcroft, L.J.; Milfont, T.L. The use (and abuse) of the new environmental paradigm scale over the last 30 years: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthey, G.T.; Whiteman, G.; Elmes, M. Place and Sense of Place: Implications for Organizational Studies of Sustainability. J. Manag. Inq. 2014, 23, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | This Study | Prince Rupert |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 28 | 12,687 |

| First Nation/Indian Band | 28.60% | 33.50% |

| Male | 46.40% | 50.70% |

| Age (years) | 45.9 ± 2.7 | 39.7 |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 60.70% | 10.80% |

| Median Employment Income | CAD 50,000–59,999 | CAD 57,620 |

| Years in the Area | 25.1 ± 3.2 |

| Metric | Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Mean | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEP | We are approaching the limit of the number of people the earth can support. | 14% | 46% | 14% | 25% | 0% | 3.5 | 0.2 |

| NEP | Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs. | 0% | 29% | 29% | 29% | 14% | 2.7 | 0.2 |

| NEP | When humans interfere with nature it often produces disastrous consequences. | 18% | 46% | 25% | 4% | 7% | 3.6 | 0.2 |

| NEP | Human ingenuity will ensure that we do NOT make the earth unlivable. | 4% | 14% | 43% | 36% | 4% | 2.8 | 0.2 |

| NEP | Humans are severely abusing the environment. | 39% | 43% | 4% | 7% | 7% | 4.0 | 0.2 |

| NEP | The earth has plenty of natural resources if we just learn how to develop them. | 21% | 39% | 18% | 21% | 0% | 3.6 | 0.2 |

| NEP | Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist. | 64% | 25% | 7% | 0% | 4% | 4.5 | 0.2 |

| NEP | The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of modern industrial nations. | 0% | 11% | 21% | 46% | 21% | 2.2 | 0.2 |

| NEP | Despite our special abilities humans are still subject to the laws of nature. | 50% | 50% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 4.5 | 0.1 |

| NEP | The so-called “ecological crisis” facing humankind has been greatly exaggerated. | 0% | 7% | 21% | 32% | 39% | 2.0 | 0.2 |

| NEP | The earth is like a spaceship with very limited room and resources. | 18% | 54% | 14% | 7% | 7% | 3.7 | 0.2 |

| NEP | Humans were meant to rule over the rest of nature. | 0% | 11% | 21% | 36% | 32% | 2.1 | 0.2 |

| NEP | The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset. | 25% | 46% | 7% | 21% | 0% | 3.8 | 0.2 |

| NEP | Humans will eventually learn enough about how nature works to be able to control it. | 0% | 25% | 0% | 64% | 11% | 2.4 | 0.2 |

| NEP | If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe. | 39% | 36% | 18% | 4% | 4% | 4.0 | 0.2 |

| SERV | How I manage the land, both for plants and animals and for future people, reflects my sense of responsibility to and so stewardship of the land. | 61% | 32% | 4% | 4% | 0% | 4.5 | 0.1 |

| SERV | There are landscapes that say something about who we are as a community, a people. | 32% | 64% | 4% | 0% | 0% | 4.3 | 0.1 |

| SERV | I often think of some wild places whose fate I care about and strive to protect, even though I may never see them myself. | 46% | 39% | 14% | 0% | 0% | 4.3 | 0.1 |

| SERV | I have strong feelings about nature (including all plants, animals, the land, etc.), and these views are part of who I am and how I live my life. | 36% | 50% | 11% | 4% | 0% | 4.2 | 0.2 |

| SERV | Plants and animals, as part of the interdependent web of life, are like ‘kin’ or family to me, so how we treat them matters. | 43% | 46% | 11% | 0% | 0% | 4.3 | 0.1 |

| SERV | My health, the health of my family, and the health of others who I care about is dependent on the natural environment. | 43% | 57% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 4.4 | 0.1 |

| SERV | Humans have a responsibility to account for our own impacts to the environment because they can harm other people. | 57% | 43% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 4.6 | 0.1 |

| Quote | Respondent |

|---|---|

| Lack of Training Regarding How the RCMP Deal with Carnivores | |

| They’re doing the best they can with the training they have. | 1451 |

| I think they do a good job of what they do and their interaction with it. But I think it should be more on the Conservation Officer level because it would be better suited in implementing the new guidelines, regulations and what have you and it should be… I wouldn’t want to say entirely separate. But you know, everyone specializes in their own area and it would be better protection for a conservation officer to intervene and… than it would be for an RCMP officer who’s got everything else on their plate. | 8576 |

| If you had like another conservation officer that was better trained and equipped to defuse a situation with a carnivore you know it wouldn’t come down to it being like such a, you know, where the carnivore often, he gets killed […] I mean, that’s an issue with even like mental health and with police officers, like not… not knowing, not being trained, like we need more training and just like specialization, so like, I guess, carnivore training and you know, and Mental Health Training. | 2656 |

| I think they’re trying their best to keep the population of Prince Rupert safe. I would love to give them some support in the work that they do to be able to do it more effectively in regards to carnivores and different animals within the city limits or outward—the… the area limits anyway. And I think that there are some issues that need to be looked upon, but I think it’s just easily fixed by making sure that they feel properly equipped with the ability to be able to deal with those situations, which I don’t think they feel completely comfortable with that right now. | 2713 |

| They’re not because they gotta wait for the Conservation Officers to do anything so… we need the conservation officer is what we need. | 2992 |

| I think most of the time, the RCMP calls the Conservation Officer which is the appropriate response generally. I don’t think the RCMP really interacts too much with them. I only ever hear about the Conservation Officer really attending any kind of incident with an animal. So, I don’t think they’re… I don’t think they’re necessarily prepared to do that, right? Like, I’m sure… I’m sure they have some kind of protocol in place | 3739 |

| They don’t really have enough knowledge or background and their scopes are too large in order to really be effective. I don’t feel that they’re effective whatsoever. | 5146 |

| I think that’s out of their realm. They’re police officers. They… what do they know about conservation? | 5279 |

| It’s not in their forte. It’s not in their job description. I don’t fault them for what they do. But I don’t think it’s a way to manage anything | 5270 |

| I believe they try to do the best they can. I think they have limited resources. | 6247 |

| I think they just, they can do all they can do is do what they can do, right? We’ve got a lot more pressing issues usually. I think it’s… it’s more for putting animals down that have been injured with cars, and I think they’re doing a fine job. | 7190 |

| I think they have to do their job. And if there’s no Conservation Officer they might have to put something down. | 7698 |

| They’re handling it good in the sense of what they’re able to do, but same time like if we had the Conservation Officers in this area, they would probably prevent like to the extreme measure where we have to put down a bear or Wolf. | 7836 |

| I think they do the best they can, but they can’t really cope with them. […] I just don’t think they’re probably properly trained to use the dart guns and to be able to handle them and transport them and that kind of thing. | 8023 |

| Generally Negative View of How RCMP Deals with Carnivores | |

| They’re not. They only know to shoot em. Yep, that’s it. Kill em. | 3317 |

| I think they shoot them too often. That’s my impression. It’s… they go out and ‘blam.’ Yeah. Well, they’re not trained to do otherwise. Yeah. So… and their duty is more to protect the people than the animals. So that’s sort of the way they look at things. Yeah. | 7887 |

| They’re not trained for it, and I don’t think they have the right attitude about it. They’re more take charge, shoot the thing, you know, they didn’t to their… to their credit. No, I don’t think they’re an adequate replacement to a Conservation Officer. | 8141 |

| The Royal Canadian Mounted Police are called on really because you don’t have a conservation officer in this area. And people believe that attention is required in one form or another when there’s encounters. I know as a last resort, the RCMP do… do react. | 8510 |

| They don’t know wildlife so it’s automatic guns, right? So I guess they’re doing what… what they can for the people but I think it’s wrong. They should actually have someone that can dart the animal and take them out and if they know for sure that animal has come back with a vengeance, then to do away with it. But other than that… | 9296 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leveridge, M.C.; Davis, A.Y.; Dumyahn, S.L. Evaluating Attitudes towards Large Carnivores within the Great Bear Rainforest. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313270

Leveridge MC, Davis AY, Dumyahn SL. Evaluating Attitudes towards Large Carnivores within the Great Bear Rainforest. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313270

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeveridge, Max C., Amélie Y. Davis, and Sarah L. Dumyahn. 2021. "Evaluating Attitudes towards Large Carnivores within the Great Bear Rainforest" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313270

APA StyleLeveridge, M. C., Davis, A. Y., & Dumyahn, S. L. (2021). Evaluating Attitudes towards Large Carnivores within the Great Bear Rainforest. Sustainability, 13(23), 13270. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313270