No One Is Leaving This Time: Social Media Fashion Brand Communities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The impact of peer influence and self-disclosure as antecedents of SCE in SMFBCs;

- The effect of SCE on loyalty to SMFBCs;

- Self-disclosure as a mediator between peer influence and SCE in SMFBCs.

2. Literature Review

3. Theories and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Peer Influence

3.2. Self-Disclosure

3.3. Sustaining Consumer Engagement and Loyalty in SMFBCs

4. Methodology

4.1. Profile of the Respondents

4.2. Measurement Scales

5. Measurement Model

5.1. Data Analysis and Results

5.2. Common Method Bias

5.3. Structural Model

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Further Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Peer Influence | Some members on this fashion brand’s fan page could push me into continuing to engage in this fashion brand’s fan page | [125,126] |

| At times, I keep on interacting on this fashion brand’s fan page because some members have encouraged me to | ||

| At times, I’ve felt pressured to keep on engaging on this fashion brand’s fan page, because some members have urged me too. | ||

| When I see members of this fashion brand’s fan page participating in activities on this page, I feel pressured to also participate. | ||

| Self-Disclosure | I usually talk about my personal experiences on this fashion brand’s fan page | [93] |

| I feel sincere when I reveal my own feelingsand experiences on this fashion brand’s fan page | ||

| I often disclose intimate, personal things about myself on this fashion brand’s fan page | ||

| My conversations last long when I amDiscussing about myself on this fashion brand’s fan page | ||

| SCE in SMFBC | When online on Facebook, I constantly participate in activities on this fashion brand’s fan page. | [4,127] |

| When I engage in this fashion brand’s fan page, I keep on reading other peoples comment and conversations | ||

| I continuously like, share and comment on post from this fashion brand’s fan page | ||

| I spend a lot of time participating in activities on this fashion brand’s fan page, compared to other brand pages. | ||

| Loyalty to SMFBC | I will frequently re-participate in activities of this fashion brand’s fan page in the future | [113,128] |

| I intend to revisit this fashion brand’s fan page | ||

| I would recommend this fashion brand’s fan page to my friends/relatives. | ||

| I will hardly consider switching to another fashion brand’s fan page |

References

- Tajvidi, R.; Karami, A. The effect of social media on firm performance. Comput. Human Behav. 2021, 115, 105174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Blas, S.; Bigné, E.; Buzova, D. Facebook brand community bonding: The direct and moderating effect of value creation behaviour. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, V.; Peltier, J.W.; Schultz, D.E. Social media and consumer engagement: A review and research agenda. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2016, 10, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lee, M.K.O.; Liu, R.; Chen, J. International Journal of Information Management Trust transfer in social media brand communities: The role of consumer engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Lopez, C.; Molina, A. Computers in Human Behavior An integrated model of social media brand engagement. Comput. Human Behav. 2019, 96, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.; Ha, S.; Lee, K. How to measure social capital in an online brand community? A comparison of three social capital scales. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A. Data extraction and preparation to perform a The example of a Facebook fashion brand page. In Proceedings of the 12th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, K.H. Sustainable fashion index model and its implication. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Gao, F.; Tan, M.; Peng, P. Fashion analysis and understanding with artificial intelligence. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.; Hennigs, N.; Langner, S. Spreading the Word of Fashion: Identifying Social Influencers in Fashion Marketing Spreading the Word of Fashion: Identifying Social Influencers in Fashion Marketing. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2012, 2685, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Mishra, S. Luxury fashion consumption in sharing economy: A study of Indian millennials Luxury fashion consumption in sharing economy: A study of Indian millennials. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2020, 11, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, I.M.; Stubbs, W. Circular fashion supply chain through textile-to-textile recycling. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godart, F.C. Poetics Culture, structure, and the market interface: Exploring the networks of stylistic elements and houses in fashion. Poetics 2018, 68, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Daniel, T.K. How social media shapes the fashion industry: The spillover e ff ects between private labels and national brands. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 86, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, G.; Lancaster, G. Social media brand perceptions of millennials. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 977–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martín-Consuegra, D.; Faraoni, M.; Díaz, E.; Ranfagni, S.; Faraoni, M.; Díaz, E.; Ranfagni, S. Exploring relationships among brand credibility, purchase intention and social media for fashion brands: A conditional mediation model. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2018, 9, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, K.H. Influence of integration on interactivity in social media luxury brand communities. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, S.; Loureiro, C.; Maximiano, M.; Panchapakesan, P. Engaging fashion consumers in social media: The case of luxury brands. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2018, 11, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ho, C.W.; Wang, Y.B. Re-purchase intentions and virtual customer relationships on social media brand community. Human-centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yi, D.; Phang, C.W.; Lu, X.; Tan, C.-H.; Sutanto, J. The Role of Marketer- and User-generated Content in Sustaining the Growth of a Social Media Brand Community. In Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lee, F. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services Examining customer engagement and brand intimacy in social media context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Rajala, R.; Dwivedi, Y. Why people use online social media brand communities:A consumption value theory perspective. Online Inf. Rev. 2018, 42, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Kim, S.S.; Morris, J.G.; Ray, S.; Kim, S.S.; Morris, J.G. The Central Role of Engagement in Online Communities The Central Role of Engagement in Online Communities. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.; Rahman, Z. The impact of online brand community characteristics on customer engagement: An application of Stimulus-Organism-Response paradigm. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwreikat, A.A.; Rjoub, H. Impact of Mobile Ad Wearout on Consumer Irritation, Perceived Intrusiveness, Engagement, and Loyalty: A PLS-SEM Analysis. J. Organ. End User Comput. (JOEUC) 2021, 33, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.H.; Nayak, R.; Long, N.V.T. The Impact of Electronic-Word-of Mouth on e-Loyalty and C onsumers’ e-Purchase Decision Making Process: A Social Media Perspective. Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2019, 10, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, B.; Wilson, B. Computers in Human Behavior Investigating the role of identi fi cation for social networking Facebook brand pages. Comput. Human Behav. 2018, 84, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asperen, M. Van; Rooij, P. De; Dijkmans, C. Engagement-Based Loyalty: The Effects of Social Media Engagement on Customer Loyalty in the Travel Industry Engagement-Based Loyalty: The Effects of Social Media. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2018, 19, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Yang, C.; Hsu, C.; Wang, J. Longitudinal study of leader influence in sustaining an online community. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Rahman, Z. Understanding customer participation in online brand communities: Literature review and future research agenda. Qual. Mark. Res. 2017, 20, 306–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, Z.L.; Wahab, H.A.; Waqas, M. Unveiling drivers and brand relationship implications of consumer engagement with social media brand posts. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.W.; Ahuja, M.K.; Suh, A.; Yap, L.X. Sustainability of a virtual community: Integrating individual and structural dynamics. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chahal, H.; Rani, A. How trust moderates social media engagement and brand equity. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2017, 11, 312–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P.; Evers, U.; Miles, M.; Daly, T. Customer engagement with tourism social media brands. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSI. Research Priorities. 2018. Available online: https://www.msi.org/research/2016-2018-research-priorities/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Fletcher-Brown, J.; Turnbull, S.; Viglia, G.; Chen, T.; Pereira, V. Vulnerable consumer engagement: How corporate social media can facilitate the replenishment of depleted resources. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Andreassen, T.W. The S-D logic-informed “hamburger” model of service innovation and its implications for engagement and value. J. Serv. Mark. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z.; Hollebeek, L.D. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A solicitation of congruity theory. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Paruthi, M.; Islam, J.; Hollebeek, L.D. Telematics and Informatics The role of brand community identification and reward on consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty in virtual brand communities. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 46, 101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, H. Exploring the impact of religiousness and culture on luxury fashion goods purchasing intention A behavioural study on Nigerian. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 768–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falade, T. Globalization and the Cultural/Creative Industries: An Assessment of Nigeria’ s Position in the Global Space. J. Adv. Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 2, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. Examining the effects of brand love and brand image on customer engagement: An empirical study of fashion apparel brands. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2016, 7, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C. User engagement in social media—An explorative study of Swedish fashion brands. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentina, I.; Guilloux, V.; Micu, A.C.; Pentina, I. Exploring Social Media Engagement Behaviors in the Context of Luxury Brands Exploring Social Media Engagement Behaviors in the Context of Luxury Brands. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M.; Ostermaier, A. Peer Influence on Managerial Honesty: The Role of Transparency and Expectations. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, Y.H.; Daly, A.J. The networked leader: Understanding peer influence in a system wide leadership team. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, L.E.; Greenfield, P.M.; Hernandez, L.M.; Dapretto, M. Peer Influence Via Instagram: Effects on Brain and Behavior in Adolescence and Young Adulthood. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lee, S.H.; Copeland, L.R. Social media and Chinese consumers’ environmentally sustainable apparel purchase intentions. Asia Pacific J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, S.; Deniz, E.; Akin, N. Determining the Factors That Influence the Intention To Purchase Luxury Fashion Brands of Young Consumers. Ege Acad. Rev. 2019, 19, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Ko, E.; Chae, H.; Mattila, P. Understanding fashion consumers’ attitude and behavioral intention toward sustainable fashion products: Focus on sustainable knowledge sources and knowledge types. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2016, 7, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobia, C.; Liu, C. Teen girls’ adoption of a virtual fashion world. Young Consum. 2016, 17, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolske, K.S.; Gillingham, K.T.; Schultz, P.W. Peer influence on household energy behaviours. Nat. Energy 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Davison, R.M. Social Support, Source Credibility, Social Influence, and Impulsive Purchase Behavior in Social Commerce. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2019, 23, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Lee, Z.W.Y.; Chan, T.K.H. Self-disclosure in social networking sites benefits and social influence. Internet Res. 2013, 25, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabisch, J.A.; Milne, G.R. Self-disclosure on the web role of regulatory focus. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2013, 11, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiansyah, Y.; Harrigan, P.; Soutar, G.N.; Daly, T.M.; Ardiansyah, Y.; Harrigan, P.; Soutar, G.N.; Daly, T.M. Antecedents to Consumer Peer Communication through Social Advertising: A Self-Disclosure Theory Perspective Antecedents to Consumer Peer Communication through Social Advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 18, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lin, S.; Carlson, J.R.; Ross, W.T. Brand engagement on social media: Will firms’ social media efforts influence search engine advertising effectiveness? J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 526–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, A.; Bonifield, C.M.; Elhai, J.D. Modeling consumer engagement on social networking sites: Roles of attitudinal and motivational factors. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzuti, T.; Leonhardt, J.M.; Warren, C. Certainty in Language Increases Consumer Engagement on Social Media. J. Interact. Mark. 2021, 53, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, A.; Tägt Ljungberg, N. Consumer Engagement on Instagram: Viewed through the Perspectives of Social Influence and Influencer Marketing; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ananda, A.S.; Hernández-García, Á.; Acquila-Natale, E.; Lamberti, L. What makes fashion consumers “click”? Generation of eWoM engagement in social media. Asia Pacific J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 398–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D. College students’ academic motivation, media engagement and fear of missing out. Comput. Human Behav. 2015, 49, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Hwang, Y.; Kim, S.; Biocca, F.A. How social media engagement leads to sports channel loyalty: Mediating roles of social presence and channel commitment. Comput. Human Behav. 2015, 46, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletikosa Cvijikj, I.; Michahelles, F. Online engagement factors on Facebook brand pages. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2013, 3, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Hosanagar, K.; Nair, H.S. Advertising Content and Consumer Engagement on Social Media: Evidence from Facebook. Management Science Published online in Articles in Advance. Manage. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luarn, P.; Lin, Y.F.; Chiu, Y.P. Influence of Facebook brand-page posts on online engagement. Online Inf. Rev. 2015, 39, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osemeahon, O.S. Linking FOMO and Smartphone Use to Social Media Brand Communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, L.; Wang, K. Investigating virtual community participation and promotion from a social influence perspective. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 1229–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenders, R.T.A.J. Modeling social influence through network autocorrelation: Constructing the weight matrix. Soc. Netw. 2002, 24, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Computers in Human Behavior Persuasive messages on information system acceptance: A theoretical extension of elaboration likelihood model and social influence theory. Comput. Human Behav. 2013, 29, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.F.; Miller, C.E. Group Decision Making and Normative Versus Informational Influence: Effects of Type of Issue and Assigned Decision Rule. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, P. Identifying the factors that influence eWOM in SNSs: The case of Chile. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 0487, 852–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.R.; Casterline, J.B. Social learning, social influence, and new models of fertility. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1996, 22, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, L.M.; Naidoo, R. Factors explaining user loyalty in a social media-based brand community. SA J. Inf. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.; Chen, K. The effects of hedonic/utilitarian expectations and social influence on continuance intention to play online games. Internet Res. 2014, 24, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P. Learning virtual community loyalty behavior from a perspective of social cognitive theory. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2010, 26, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapna, R.; Umyarov, A.; Bapna, R.; Umyarov, A. Do Your Online Friends Make You Pay? A Randomized Field Experiment on Peer Influence in Online Social Networks Do Your Online Friends Make You Pay? A Randomized Field Experiment on Peer Influence in Online Social Networks. Manage. Sci. 2015, 61, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, A.M.; North, E.A.; Ferguson, S. Chapter 6. Peers and Engagement; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780128134139. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel, K.; Ramani, G.B. Handbook of Social Influences in School Contexts: Social-Emotional, Motivation, and Cognitive Outcomes; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Weijer, S.G.A.; Beaver, K.M. An Exploration of Mate Similarity for Criminal Offending Behaviors: Results from a Multi-Generation Sample of Dutch Spouses. Psychiatr. Q. 2017, 88, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.; Huang, M.; Xiao, B. Promoting continual member participation in fi rm-hosted online brand communities: An organizational socialization approach. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Min, Q.; Han, S. Understanding users’ continuous content contribution behaviours on microblogs: An integrated perspective of uses and gratification theory and social influence theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiyi, Z.; Amy, Z.; Jiping, H.; Robert, E.K.; Kittur, A. Effects of peer feedback on contribution: A field experiment in Wikipedia. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sungwook, L.; Do-hyung, P.; Han, I. Computers in Human Behavior New members’ online socialization in online communities: The effects of content quality and feedback on new members’ content-sharing intentions. Comput. Human Behav. 2014, 30, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, A. Reciprocity of Interpersonal Exchange. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 1973, 3, 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Kashian, N.; Jang, J.; Yun, S.; Dai, Y.; Walther, J.B. Computers in Human Behavior Self-disclosure and liking in computer-mediated communication. Comput. Human Behav. 2017, 71, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreager, D.A.; Schaefer, D.R.; Davidson, K.M.; Zajac, G.; Haynie, D.L.; De Leon, G. Evaluating peer-influence processes in a prison-based therapeutic community: A dynamic network approach. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 203, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aihwa, C.; Sara, H.H.; Timmy, H.T. Online brand community response to negative brand events: The role of group eWOM. Internet Res. 2013, 23, 486–506. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L.C.; Chih, W.H.; Liou, D.K. Investigating community members’ eWOM effects in Facebook fan page. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 978–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Kwok, R.C.; Benjamin, P.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. Information & Management The influence of role stress on self-disclosure on social networking sites: A conservation of resources perspective. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rialti, R.; Scuola, F. Co-creation experiences in social media brand communities Analyzing the main types of Comunidades de marca de medios n de sociales y co-creaci o experiencias n sobre los principales tipos. Spanish J. Mark. 2018, 22, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reza, M.; Laroche, M.; Richard, M. Computers in Human Behavior Testing an extended model of consumer behavior in the context of social media-based brand communities. Comput. Human Behav. 2016, 62, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, P.; Rita, P.; Raposo, Z. On the relationship between consumer-brand identi fi cation, brand community, and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, S.; Elena, D.-B.; Mariola, P. The need to belong and self-disclosure in positive word-of-mouth behaviours:The moderating effect of self–brand connection. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.; Iii, S.M.; Pervan, S.J.; Kortt, M. Facebook, self-disclosure, and brand-mediated intimacy: Identifying value creating behaviors. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 502, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Town, J.P.; Harvey, J.H. Self-Disclosure, Attribution, and Social Interaction. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1981, 44, 291–300. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3033898 (accessed on 18 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Preece, J.; Preece, J. Sociability and usability in online communities: Determining and measuring success Sociability and usability in online communities: Determining and measuring success. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2010, 20, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D.P. Mediating Variable, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 15, ISBN 9780080970868. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Yeh, C. Corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty in intercity bus services. Transp. Policy 2017, 59, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, E.Y. Marketing mix, customer value, and customer loyalty in social commerce. Internet Res. 2018, 1066–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Zhang, D. The effects of sense of presence, sense of belonging, and cognitive absorption on satisfaction and user loyalty toward an immersive 3D virtual world. In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Berlin, Germary, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Perry, P.; Gadzinski, G. The implications of digital marketing on WeChat for luxury fashion brands in China. J. Brand Manag. 2019, 26, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Haghighi, M. Business intelligence in online customer textual reviews: Understanding consumer perceptions and influential factors. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, M.; Schnebelen, S.; Schäfer, D. Antecedents and consequences of the quality of e-customer-to-customer interactions in B2B brand communities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Jun, M.; Kim, M. Impact of online community engagement on community loyalty and social well-being. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2019, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.H. Motivations of facebook users for responding to posts on a community page. In International Conference on Online Communities and Social Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Shin, D.H. The effect of customers’ perceived benefits on virtual brand community loyalty. Online Inf. Rev. 2016, 40, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woisetschläger, D.M.; Hartleb, V.; Blut, M.; Woisetschl, D.M.; Hartleb, V. How to Make Brand Communities Work: Antecedents and Consequences of Consumer Participation How to Make Brand Communities Work: Antecedents and Consequences of Consumer Participation. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2008, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xiao, T.; Wu, X.; Wu, H. More is better ? The influencing of user involvement on user loyalty in online travel community in online travel community. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2017, 1665, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, O.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Self-presentation, privacy and electronic word-of-mouth in social media. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, M.; Akareem, H.S. Friends with benefits: Can firms benefit from consumers’ sense of community in brand Facebook pages? Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 947–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunaiya, O.; Agoyi, M.; Osemeahon, O.S. Social TV Engagement for Increasing and Sustaining Social TV Viewers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hopkins, L.; Georgia, M.; College, S. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. Extending the experience construct: An examination of online grocery shopping construct. Eur. J. Mark. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Rosenberger, P.J. The influence of perceived social media marketing elements on consumer—Brand engagement and brand knowledge. Asia Pacific J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 695–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Cranbury, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Phou, S. A closer look at destination: Image, personality, relationship and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santor, D.A.; Deanna, M.; Kusumakar, V. Measuring peer pressure, popularity, and conformity in adolescent boys and girls: Predicting school performance, sexual attitudes, and substance abuse. J. Youth Adolesc. 2000, 22, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Cai, X.; Liu, Q.; Fan, W. International Journal of Information Management Examining continuance use on social network and micro-blogging sites: Different roles of self-image and peer influence. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Lu, H. Consumer behavior in online game communities: A motivational factor perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 1642–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCE | 0.803 | 0.844 | 0.906 | 0.762 |

| 0.797 | ||||

| 0.818 | ||||

| 0.763 | ||||

| Loyalty to SMFBC | 0.819 | 0.837 | 0.902 | 0.754 |

| 0.854 | ||||

| 0.879 | ||||

| 0.835 | ||||

| Peer Influence | 0.790 | 0.831 | 0.898 | 0.746 |

| 0.745 | ||||

| 0.878 | ||||

| 0.822 | ||||

| Self-Disclosure | 0.839 | 0.833 | 0.900 | 0.749 |

| 0.874 | ||||

| 0.842 | ||||

| 0.774 |

| SCE | Loyalty to SMFBC | Peer Influence | Self-Disclosure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCE | 0.873 | |||

| Loyalty to SMFBC | 0.493 | 0.869 | ||

| Peer Influence | 0.535 | 0.427 | 0.864 | |

| Self-Disclosure | 0.710 | 0.510 | 0.545 | 0.866 |

| SCE | Loyalty to SMFBC | Peer Influence | Self-Disclosure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCE | ||||

| Loyalty to SMFBC | 0.581 | |||

| Peer Influence | 0.635 | 0.509 | ||

| Self-Disclosure | 0.847 | 0.607 | 0.648 |

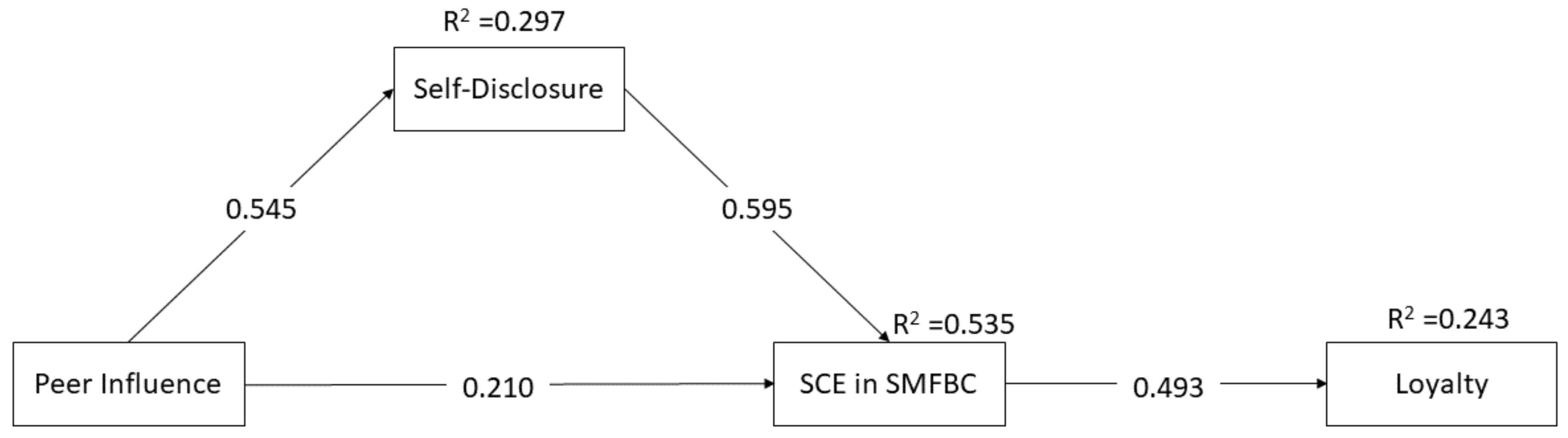

| Coefficient (β) | T Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCE -> Loyalty to SMFBC | 0.493 | 8.818 | 0.000 |

| Peer Influence -> SCE | 0.210 | 4.252 | 0.000 |

| Peer Influence -> Self-Disclosure | 0.545 | 9.134 | 0.000 |

| Self-Disclosure -> SCE | 0.595 | 10.957 | 0.000 |

| Indirect Effect | |||

| Peer Influence -> Self-Disclosure -> SCE | 0.324 | 6.861 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diachi, A.C.; Tansu, A.; Osemeahon, O.S. No One Is Leaving This Time: Social Media Fashion Brand Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12957. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132312957

Diachi AC, Tansu A, Osemeahon OS. No One Is Leaving This Time: Social Media Fashion Brand Communities. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):12957. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132312957

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiachi, Albert Chukwunonso, Ayşe Tansu, and Oseyenbhin Sunday Osemeahon. 2021. "No One Is Leaving This Time: Social Media Fashion Brand Communities" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 12957. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132312957

APA StyleDiachi, A. C., Tansu, A., & Osemeahon, O. S. (2021). No One Is Leaving This Time: Social Media Fashion Brand Communities. Sustainability, 13(23), 12957. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132312957