Tourism, Empowerment and Sustainable Development: A New Framework for Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Meanings and Applications of Power and Empowerment

Empowerment is understood as the activation of the confidence and capabilities of previously disadvantaged or disenfranchised individuals or groups so that they can exert greater control over their lives, challenge unequal power relations, mobilize resources to meet their needs, and work to achieve social justice.[33], p. 115.

3. Empowerment in Tourism Research

4. Empowerment Frameworks Designed for Tourism Studies

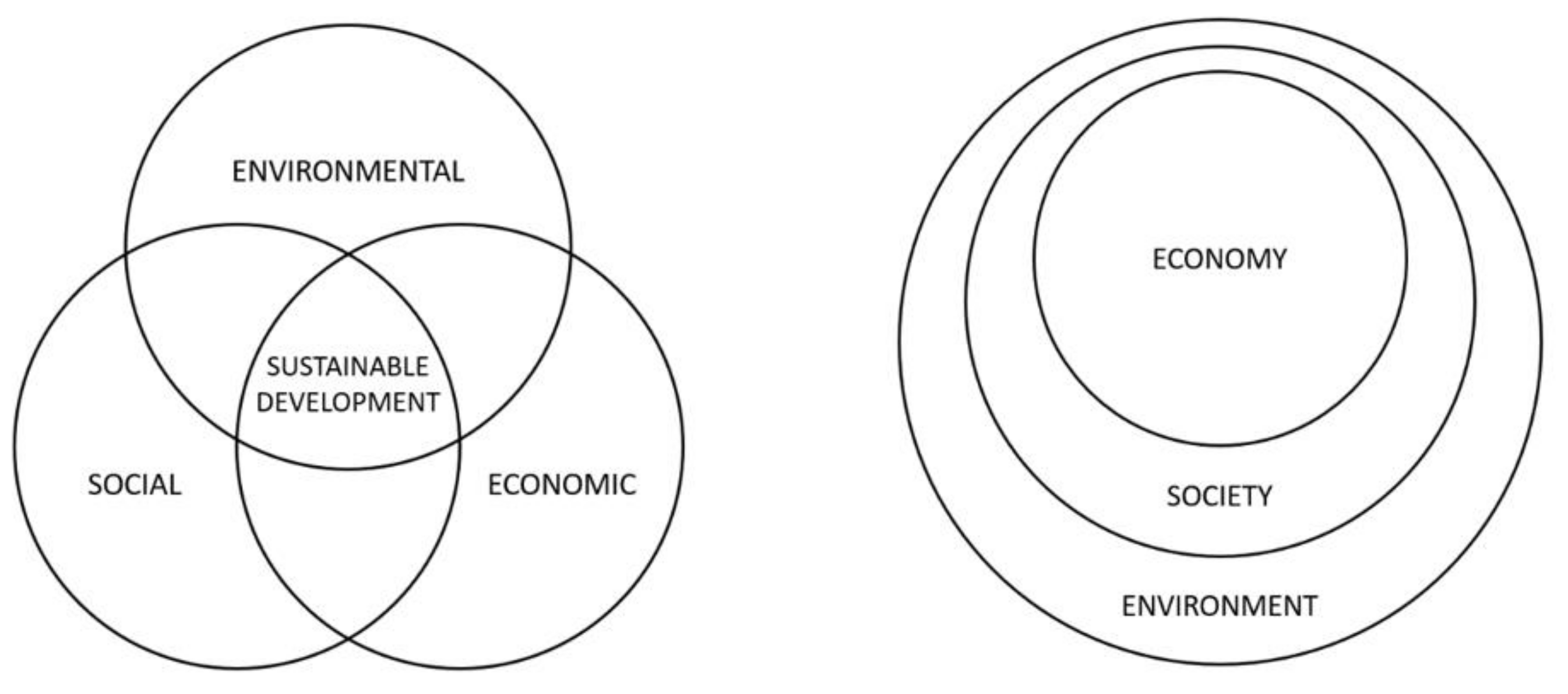

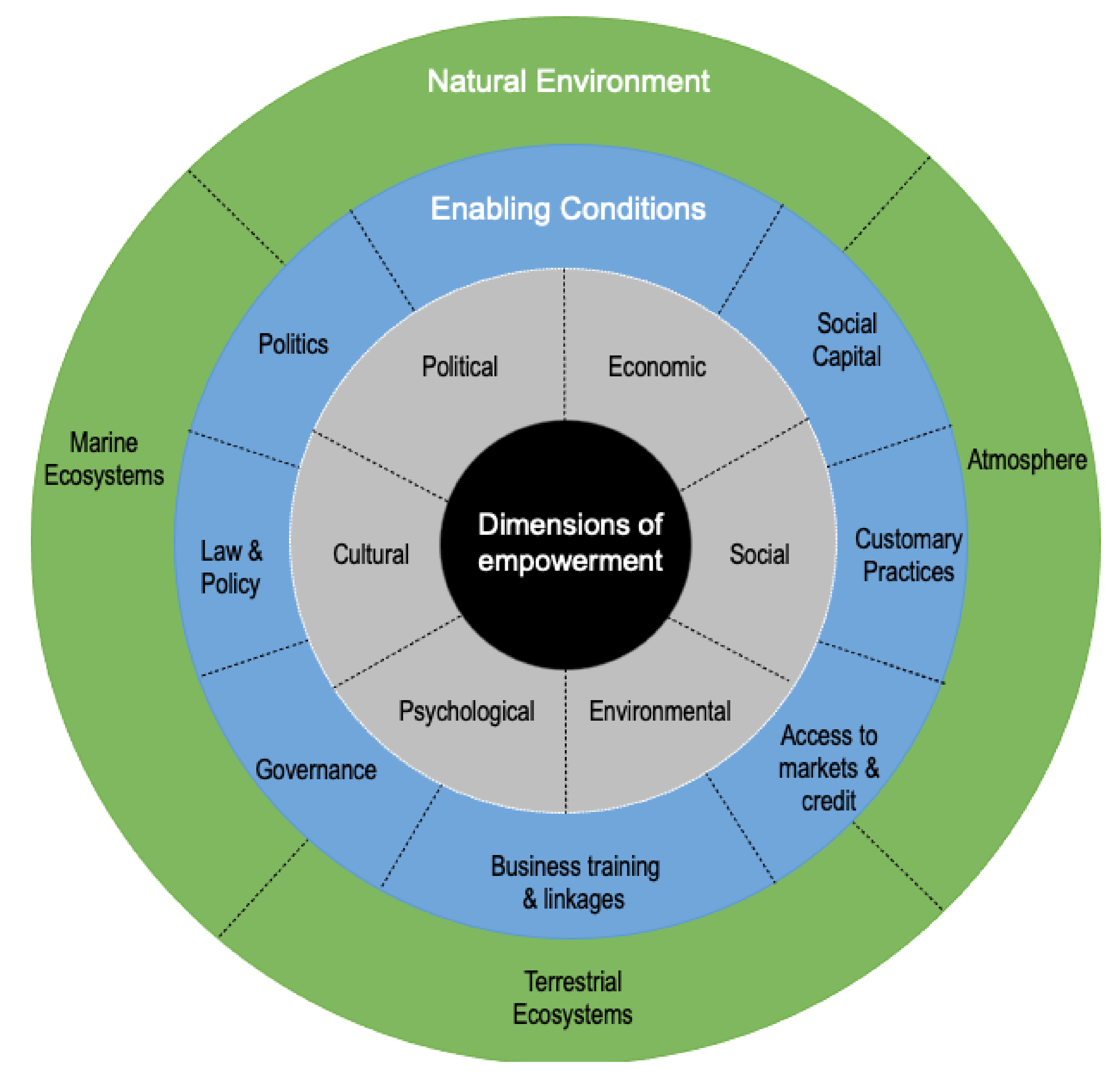

5. A New Framework Combining Empowerment and Sustainable Development

5.1. The Three Natural Environment Dimensions

5.2. The Seven Enabling Conditions

5.3. The Six Dimensions of Empowerment

6. Application of the Empowerment Framework

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the Empowerment of Local Communities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parpart, J.L.; Rai, S.M.; Staudt, K.A. Rethinking Empowerment: Gender and Development in a Global/Local World; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sukarieh, M.; Tannock, S. In the Best Interests of Youth or Neoliberalism? The World Bank and the New Global Youth Empowerment Project. J. Youth Stud. 2008, 11, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R. Improving Development Ownership Among Vulnerable People: Challenges of NGOs’ Community Empowerment Projects in Bangladesh. Asian Soc. Work. Policy Rev. 2014, 8, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batliwala, S. Taking the Power out of Empowerment—An Experiential Account. Dev. Pract. 2007, 17, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, J. Empowerment Examined: An Exploration of the Concept and Practice of Women’s Empowerment in Honduras; Durham University: Durham, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Church, A. Coles, T. Tourism, Power and Space; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands, J. Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, L.E. The Greta Effect: How does Greta Thunberg use the Discourse of Youth in her Movement for Climate Justice. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Fieldwork in Tourism: Methods, Issues and Reflections; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal, C.; Novelli, M. Power in Community-Based Tourism: Empowerment and Partnership in Bali. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Governance, the State and Sustainable Tourism: A Political Economy Approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R. Governance and Sustainable Tourism: What is the Role of Trust, Power and Social Capital? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- de Kadt, E. Tourism: Passport to Development? Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, D.W.; Cottrell, S.P. Evaluating Tourism-Linked Empowerment in Cuzco, Peru. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 56, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrein, T. Looking Back at the Parcours Arianna in the Val d’Anniviers. J. Alp. Res. 2013, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Annes, A.; Wright, W. ‘Creating a Room of One’s Own’: French Farm Women, Agritourism and the Pursuit of Empowerment. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2015, 53, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Timur, S.; Getz, D. A Network Perspective on Managing Stakeholders for Sustainable Urban Tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsop, R.; Heinson, N. Measuring Empowerment in Practice: Structuring Analysis and Framing Indicators. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3510; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pigg, K.E. Three Faces of Empowerment: Expanding the Theory of Empowerment in Community Development. J. Community Dev. Soc. 2009, 33, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. Studies in Empowerment: Introduction to the Issue. Prev. Hum. Serv. 1984, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, C.L.; O’Gorman, K.D.; MacLaren, A.C. Commercial Hospitality: A Vehicle for the Sustainable Empowerment of Nepali Women. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 23, 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, A.; Rivas, A.-M. From ‘Gender Equality and ‘Women’s Empowerment’ to Global Justice: Reclaiming a Transformative Agenda for Gender and Development. Third World Q. 2015, 36, 396–415. [Google Scholar]

- Mosedale, S. Assessing Women’s Empowerment: Towards a Conceptual Framework. J. Int. Dev. 2005, 17, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Empowerment: The Politics of Alternative Development; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, J. In Praise of Paradox: A Social Policy of Empowerment over Prevention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1981, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.D.; Zimmerman, M.A. Empowerment Theory, Research, and Application. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 569–579. [Google Scholar]

- Sofield, T.H.B. Empowerment for Sustainable Tourism Development; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, S.; Tasneem, S. Measuring ‘Empowerment’ Using Quantitative Household Survey Data. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2014, 45, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sardenberg, C. Liberal vs. Liberating Empowerment: Conceptualising Women’s Empowerment from a Latin American Feminist Perspective, in Conference: Feminism—Gender and Neo-Liberalism; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Watt, H. ‘Better Lives for All?’ The Contribution of Marine Wildlife Tourism to Development in Gansbaai, South Africa. Doctoral Thesis, Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand. in press.

- Scheyvens, R. Empowerment, in International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed.; Kobayashi, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, G.M. Tourism Research on the Caribbean: An Evaluation. Leis. Sci. 1988, 10, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The Sociology of Tourism: Approaches, Issues, and Findings. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1984, 10, 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, R. Tourism for Development: Empowering Communities; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2002; Volume 16, p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Goudie, S.C.; Khan, F.; Kilian, D. Transforming Tourism: Black Empowerment, Heritage and Identity Beyond Apartheid. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 1999, 81, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinek, A.A.; Hunt, C.A. Social Capital, Ecotourism, and Empowerment in Shiripuno, Ecuador. Int. J. Tour. Anthropol. 2015, 4, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, J.; Walter, P. How Do You Know It When You See It? Community-Based Ecotourism in the Cardamom Mountains of Southwestern Cambodia. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohori, O.; van der Merwe, P. Tourism and Community Empowerment: The Perspectives of Local People in Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M. Water and Waste Management in the Moroccan Tourism Industry: The Case of Three Women Entrepreneurs. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2012, 35, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.; Zubair, S.; Altinay, L. Politics and Tourism Destination Development: The Evolution of Power. J. Travel Res. 2016, 56, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.D.; Vázquez, A.E.G.; Ivanova, A. Women Beach and Marina Vendors in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2012, 39, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moswete, N.; Lacey, G. “Women Cannot Lead”: Empowering Women through Cultural Tourism in Botswana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 600–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, N.U.; Woosnam, K.M.; Boley, B.B. Comparing Levels of Resident Empowerment among Two Culturally Diverse Resident Populations in Oizumi, Gunma, Japan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1442–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Peng, H. Tourism development, Rights Consciousness and the Empowerment of Chinese Historical Village Communities. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Ma, J.; Notarianni, M.; Wang, S. Empowerment of Women through Cultural Tourism: Perspectives of Hui minority Embroiderers in Ningxia, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenao, M.; Basupi, B. Ecotourism Development and Female Empowerment in Botswana: A Review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, J.M.; Lendelvo, S.; Coe, K.; Rispel, M. Community Perspectives of Empowerment from Trophy Hunting Tourism in Namibia’s Bwabwata National Park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, T.; Zimmermann, F. Ecotourism as Community Development Tool—Development of an Evaluation Framework. Curr. Issues Tour. Res. 2015, 4, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sarr, B.; Sène-Harper, A.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, M.M. Tourism, Social Representations and Empowerment of Rural Communities at Langue de Barbarie National Park, Senegal. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coria, J.; Calfucura, E. Ecotourism and the Development of Indigenous Communities: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 73, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.M.; Prideaux, B. Indigenous Ecotourism in the Mayan Rainforest of Palenque: Empowerment Issues in Sustainable Development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 22, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemelin, R.H.; Koster, R.; Youroukos, N. Tangible and Intangible Indicators of Successful Aboriginal Tourism Initiatives: A Case Study of Two Successful Aboriginal Tourism Lodges in Northern Canada. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeyre, R. The Grootberg Lodge Partnership in Namibia: Towards Poverty Alleviation and Empowerment for Long-Term Sustainability? Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman, M.; Barborak, J.R.; Inamdar, N.; Stein, T. Best Practices for Tourism Concessions in Protected Areas: A Review of the Field. Forests 2011, 2, 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, H.; Reid, D.G.; George, W. Globalisation, Rural Tourism and Community Power, in Rural Tourism and Sustainable Business; Hall, D., Kirkpatrick, I., Mitchell, M., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2005; pp. 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, M.; Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, C. Empowerment and Resident Support for Tourism in Rural Central and Eastern Europe (CEE): The case of Pomerania, Poland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.W.; Makupa, E. Using Analysis of Governance to Unpack Community-Based Conservation: A Case Study from Tanzania. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 1214–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaramba, H.M.; Lovett, J.C.; Louw, L.; Chipumuro, J. Emotional Confidence Levels and Success of Tourism Development for Poverty Reduction: The South African Kwam eMakana Home-Stay Project. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G. Measuring Empowerment: Developing and Validating the Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale (RETS). Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Maruyama, N.; Woosnam, K.M. Measuring Empowerment in an Eastern Context: Findings from Japan. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L. Promoting Gender Equality and Empowering Women? Tourism and the Third Millennium Development Goal. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Promoting Women’s Empowerment through Involvement in Ecotourism: Experiences from the Third World. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 232–249. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, L.; Walter, P. Ecotourism, Gender and Development in Northern Vietnam. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellhorn, M. Development for Whom? Social Justice and the Business of Ecotourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P.F.; Pratiwi, W. Gender and Tourism in an Indonesian Village. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazamani, Y.; Hunt, C.A. Empowerment in tourism: A review of peer-reviewed literature. Tour. Rev. Int. 2017, 21, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan-Parker, D. Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.B. Sustainability, Empowerment, and Resident Attitudes toward Tourism: Developing and Testing the Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale (RETS). Doctoral Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Ramos, A. The Use of Mayan Rainforests for Ecotourism Development: An Empowerment Approach for Local Communities, in School of Business. Doctoral Thesis, James Cook University, Cairns, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ningdong, Y.; Mingqing, L. Community entrepreneurship, female elite and cultural inheritance: Mosuo women’s empowerment and the hand-weaving factory. In Tourism and Ethnodevelopment Inclusion, Empowerment and Self-Determination; de Lima, I.B., King, V.T., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon on Thames, UK, 2018; pp. 188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Movono, A.; Dahles, H. Female Empowerment and Tourism: A Focus on Businesses in a Fijian village. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Ramos, A.; Prideaux, B. Assessing Ecotourism in an Indigenous Community: Using, Testing and Proving the Wheel of Empowerment Framework as a Measurement Tool. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjuraman, V. Community-Based Ecotourism Managing to Fuel Community Empowerment? An Evidence from Malaysian Borneo. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K.D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Courtney, E.E.; Kong, S.I.; Boley, B.B. Which Construct is Better at Explaining Residents’ Involvement in Tourism; Emotional Solidarity Or Empowerment? Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K.D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Tasci, A.D.A.; Ramkissoon, H. Antecedents and Outcomes of Resident Empowerment through Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, P.W.; Peterson, N.A. Psychometric Properties of an Empowerment Scale: Testing Cognitive, Emotional, and Behavioral Domains. Soc. Work. Res. 2000, 24, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Ayscue, E.; Maruyama, N.; Woosnam, K.M. Gender and Empowerment: Assessing Discrepancies Using the Resident Empowerment through Tourism Scale. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J. An Introduction to Sustainable Development; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a 21st-Century Economist; Random House Business Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, L.; Engelbauer, M.; Job, H. Mitigating Tourism-Driven Impacts on Mangroves in Cancún and the Riviera Maya, Mexico: An Evaluation of Conservation Policy Strategies and Environmental Planning Instruments. J. Coast. Conserv. 2018, 22, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, K.; Cook, S. Luxury Tourism Investment and Flood Risk: Case Study on Unsustainable Development in Denarau Island Resort in Fiji. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 14, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carić, H. Challenges and Prospects of Valuation—Cruise Ship Pollution Case. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senigaglia, V.; Christianisen, F.; Sprogis, K.R.; Symons, J.; Bejder, L. Food-Provisioning Negatively Affects Calf Survival and Female Reproductive Success in Bottlenose Dolphins. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Eshraghi, M.; Toriman, M.E.; Ahmad, H. Sustainable Ecotourism in Desert Areas in Iran: Potential and Issue. E-BANGI J. Sains Sos. Dan Kemanus. 2010, 5, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wurl, J. Competition for Water: Consumption of Golf Courses in the Tourist Corridor of Los Cabos, BCS, Mexico. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism as a Community Industry—an Ecological Model of Tourism Development. Tour. Manag. 1983, 4, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kideghesho, J.R.; Nyahongo, J.W.; Hassan, S.N.; Tarimo, T.C.; Mbije, N.E. Factors and Ecological Impacts of Wildlife Habitat Destruction in the Serengeti Ecosystem in Northern Tanzania. Afr. J. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2006, 11, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dongre, S.M.; Poteker, G.S. Rural Needs or Tourism: The Use of Groundwater in Goa, in Water Conflicts in India: A Million Revolts in the Making; Jou, K.J., Gujja, B., Paranjape, S., Goud, V., Vispute, S., Eds.; Routledge: New Delhi, India, 2008; pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Becken, S.; Carmignani, F. Are the Current Expectations for Growing Air Travel Demand Realistic? Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Jairath, V.K. ‘Participation’ and ‘Empowerment’ in the Development Discourse Rethinking Key Concepts’, in Governance, Conflict and Civic Action; Siri, H., Eva, G., Eds.; Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, S.M.; Mohan, G. Participation: From Tyranny to Transformation: Exploring New Approaches to Participation in Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, R.; Russell, M. Sharing the Riches of Tourism in Vanuatu. Report Produced for NZAID; Massey University: Palmerston North, NZ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Matarirano, O.; Chiloane-Tsoka, G.E.; Makina, D. Tax Compliance Costs and Small Business Performance: Evidence from the South African Construction Industry. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 50, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.; Georgiou, A. The Impact of Political Instability on a Fragile Tourism Product. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooiman, J. Governing as Governance; SAGE: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. The New Governance: Governing without Government. Polit. Stud. 1996, 44, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beritelli, P.; Bieger, T.; Laesser, C. Destination Governance: Using Corporate Governance Theories as a Foundation for Effective Destination Management. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- South Pacific Tourism Organisation. Vanuatu International Arrival Statistics: July 2017; South Pacific Tourism Organisation: Suva, Fiji, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. The Social Implications of Tourist Developments. Ann. Tour. Res. 1974, 2, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxey, G. A Causation Theory of Visitor-Resident Irritants: Methodology and Research Inferences. In Proceedings of the Travel Research Assocation 6th Annual Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–11 September 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Milman, A.; Pizam, A. The Role of Awareness and Familiarity with a Destination: The Central Florida Case. J. Travel Res. 1995, 33, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, M.B. Local empowerment in a rural community through ecotourism: A case study of a women’s organization in Chira Island, Costa Rica. In Sustainable Tourism & the Millennium Development Goals: Effecting Positive Change; Bricker, K.S., Black, R., Cottrell, S., Eds.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Jänis, J. Political Economy of the Namibian Tourism Sector: Addressing Post-Apartheid Inequality through Increasing Indigenous Ownership. Rev. Afr. Polit. Econ. 2014, 41, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeyre, R. For What Stands the “B” in the CBT Concept: Community-Based or Community-Biased Tourism? Some Insights from Namibia. Tour. Anal. 2011, 16, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaiwa, J.E.; Stronza, A.L. The Effects of Tourism Development on Rural Livelihoods in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, K. The Impact of Ethnic Tourism on Hill Tribes in Thailand. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. (Eds.) Overtourism: Issues, Realities and Solutions; Walter de Gruyter Publishers: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J.M.; Novelli, M. (Eds.) Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; CABI: Wallingford, England, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Altinay, L.; Sigala, M.; Waligo, V. Social Value Creation through Tourism Enterprise. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booyens, I. Rethinking Township Tourism: Towards Responsible Tourism Development in South African Townships. Dev. South. Afr. 2010, 27, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matunga, H.; Matunga, H.; Urlich, S. From Exploitative to Regenerative Tourism: Tino Rangatiratanga and Tourism in Aotearoa New Zealand. MAI J. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Biddulph, R. Inclusive Tourism Development. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Seiver, B.; Matthews, A. Beyond Whiteness: A Comparative Analysis of Representations of Aboriginality in Tourism Destination Images in New South Wales, Australia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1298–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.; Ruhanen, L.; Whitford, M.; Lane, B. Sustainable Tourism and Indigenous Peoples; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Abington on Thames, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Utama, I.G.B.R.; Turker, S.B.; Widyastuti, N.K.; Suyasa, N.L.C.P.S.; Waruwu, D. Model of Quality Balance Development of Bali Tourism Destination. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 10, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, R. Cannibal Habits of the Common Tourist. 2013. Available online: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/cannibal-habits-of-the-common-tourist/ (accessed on 3 June 2021).

| 1 | Empowerment entails individuals or collectives gaining control over, and the capability to make purposive choices about, their lives and futures [19,20,21]. It involves awakened and increased agency [22] with individuals becoming agents of change rather than beneficiaries of ‘development’ [23]. |

| 2 | Empowerment must be claimed by individuals, it cannot be bestowed. However, third parties may initiate and facilitate empowering processes and establish conditions conducive to empowerment, such as providing resources, training and sharing knowledge [24,25]. |

| 3 | Empowerment is multi-dimensional and involves increased access to various bases of power [26], also known as economic, social, human, or political resources [22]. Crucially, despite significant attention to economic empowerment, especially with relation to women’s development, this alone does not constitute empowerment; e.g., political empowerment is a necessary condition for fundamental social change. |

| 4 | Empowerment may involve processes as outcomes [27,28,29]; it is not just a final state. Activities or actions, such as a legal rights training program for landless people, themselves may be empowering, and empowering processes may result in an altered level of power [28]. |

| 5 | The processes and outcomes of empowerment are context-specific and take “on different forms in different people and contexts” [21] p. 33, [23,25]. Thus while it might be important for oppressed minorities in a global north and global south context to be both socially and politically empowered, how this should be achieved will vary depending on context-specific variables. |

| 6 | While empowerment may involve individual, household, community or societal change, individual change alone is not sufficient to bring about societal change [6,30]. In the words of Perkins and Zimmerman [28] p. 571, societal “empowerment [is] not simply a collection of empowered individuals.” |

| 7 | While all individuals are relatively more or less advantaged than others in society [1], the focus of empowerment must be on the interests of disenfranchised and marginalised groups of society [26]. Put simply, “to be empowered, one must have been disempowered” [25] p. 244. |

| 8 | Empowerment demands changed and rebalanced power relations [26,31]. It disrupts unequal power relations [26] that constrain the choices and lives of marginalised people and prevent human flourishing. An increase in the ability of some to challenge and resist oppressive ‘power over’ may be considered a relative loss of power for others [8]. |

| Signs of Empowerment | Signs of Disempowerment | |

|---|---|---|

| Economic empowerment | Tourism brings lasting economic gains to a local community. Cash earned is shared between many households in the community. There are visible signs of improvements from the cash that is earned (e.g., houses are made of more permanent materials; more children are able to attend school). | Tourism merely results in small, spasmodic cash gains for a local community. Most profits go to local elites, outside operators, government agencies, etc. Only a few individuals or families gain direct financial benefits from tourism, while others cannot find a way to share in these economic benefits because they lack capital, experience and/or appropriate skills. |

| Psychological empowerment | Self-esteem of many community members is enhanced because of outside recognition of the uniqueness and value of their culture, their natural resources and their traditional knowledge. Access to employment and cash leads to an increase in status for traditionally low-status sectors of society e.g., youths, the poor. | Those who interact with tourists are left feeling like their culture and way of life are inferior. Many people do not share in the benefits of tourism and are thus confused, frustrated, disinterested or disillusioned with the initiative. |

| Social empowerment | Tourism maintains or enhances the local community’s equilibrium. Community cohesion is improved as individuals and families work together to build a successful tourism venture. Some funds raised are used for community development purposes, e.g., to build schools or improve water supplies. | Disharmony and social decay. Many in the community take on outside values and lose respect for traditional culture and for their elders. Disadvantaged groups (e.g., women) bear the brunt of problems associated with the tourism initiative and fail to share equitably in its benefits. Rather than cooperating, families/ ethnic or socio-economic groups compete with each other for the perceived benefits of tourism. Resentment and jealousy are commonplace. |

| Political empowerment | The community’s political structure fairly represents the needs and interests of all community groups. Agencies initiating or implementing the tourism venture seek out the opinions of a variety of community groups (including special interest groups of women, youths and other socially disadvantaged groups) and provide opportunities for them to be represented on decision-making bodies e.g., the Wildlife Park Board or the regional tourism association. | The community has an autocratic and/or self-interested leadership. Agencies initiating or implementing the tourism venture fail to involve the local community in decision-making so the majority of community members feel they have little or no say over whether the tourism initiative operates or the way in which it operates. |

| Dimension | Markers of Empowerment |

|---|---|

| Economic | Tourism brings lasting economic gains to households and offers equitable access to employment opportunities. Those from marginalised backgrounds have opportunities to gain senior positions in the tourism sector or run their own tourism-related enterprises (e.g., restaurants, craft stalls). Marginalised households are represented in local trade/commerce associations, and they can access the means of production e.g., land, capital. |

| Psychological | Respect of outsiders for the natural and cultural assets of the area leads to an enhanced sense of pride among the destination population. Increased earnings from employment and small business opportunities also leads to increases in self-esteem and social standing for formerly lower status sections of society e.g., women and ethnic minorities. Training and education opportunities, as well as interaction with tourists, enhances people’s self-confidence and broadens their engagement in society. |

| Social | Tourism creates opportunities for people to be more involved in community activities (e.g., village beautification programmes, farmer’s markets) which builds social cohesion. Tourism supports networks that bring people from different backgrounds together. Tourism contributes to creating places, infrastructure and services that benefit all local residents. |

| Cultural | Cultural heritage—customs, languages and values as well as cultural sites—is valued and respected by tourism businesses and local residents. Tourism enterprises provide authentic portrayals of culture, allowing Indigenous groups, in particular, to self-represent their culture. Those from cultural minorities have an enhanced sense of pride due to interest in their culture from tourists and the ways in which their culture is presented to tourists. |

| Political | Tourism planning processes actively seek out voices of a wide range of people in the resident community and provide opportunities for them to be represented on decision-making bodies. Local political structures provide a forum for residents to easily bring forward any concerns they have about the operations of tourism businesses or developers. |

| Environmental | Residents have an enhanced awareness of the intrinsic value of the natural environment and are involved in conservation efforts. People show willingness to change behaviours to avoid environmental degradation or risks. Tourism enterprises take a lead in implementing sustainable practices and also incorporate environmental education for guests and the resident population into their work. Local government bodies actively monitor the impacts of tourism on the environment, and ensuring regulations—as well as good conservation practices—are followed. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scheyvens, R.; van der Watt, H. Tourism, Empowerment and Sustainable Development: A New Framework for Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212606

Scheyvens R, van der Watt H. Tourism, Empowerment and Sustainable Development: A New Framework for Analysis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212606

Chicago/Turabian StyleScheyvens, Regina, and Heidi van der Watt. 2021. "Tourism, Empowerment and Sustainable Development: A New Framework for Analysis" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212606

APA StyleScheyvens, R., & van der Watt, H. (2021). Tourism, Empowerment and Sustainable Development: A New Framework for Analysis. Sustainability, 13(22), 12606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212606