Tourism and COVID-19: The Show Must Go On

Abstract

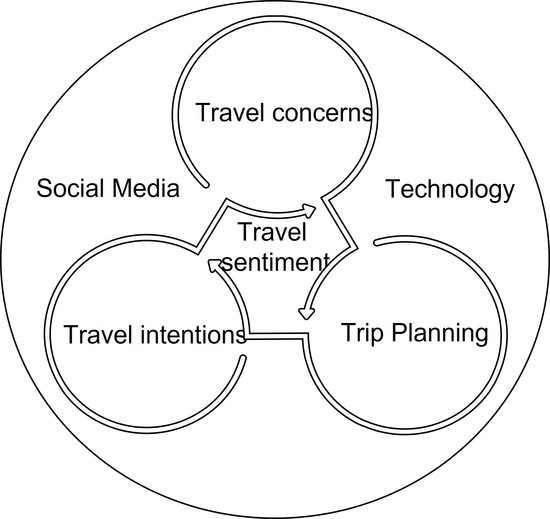

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Tourism and the COVID-19 Pandemic

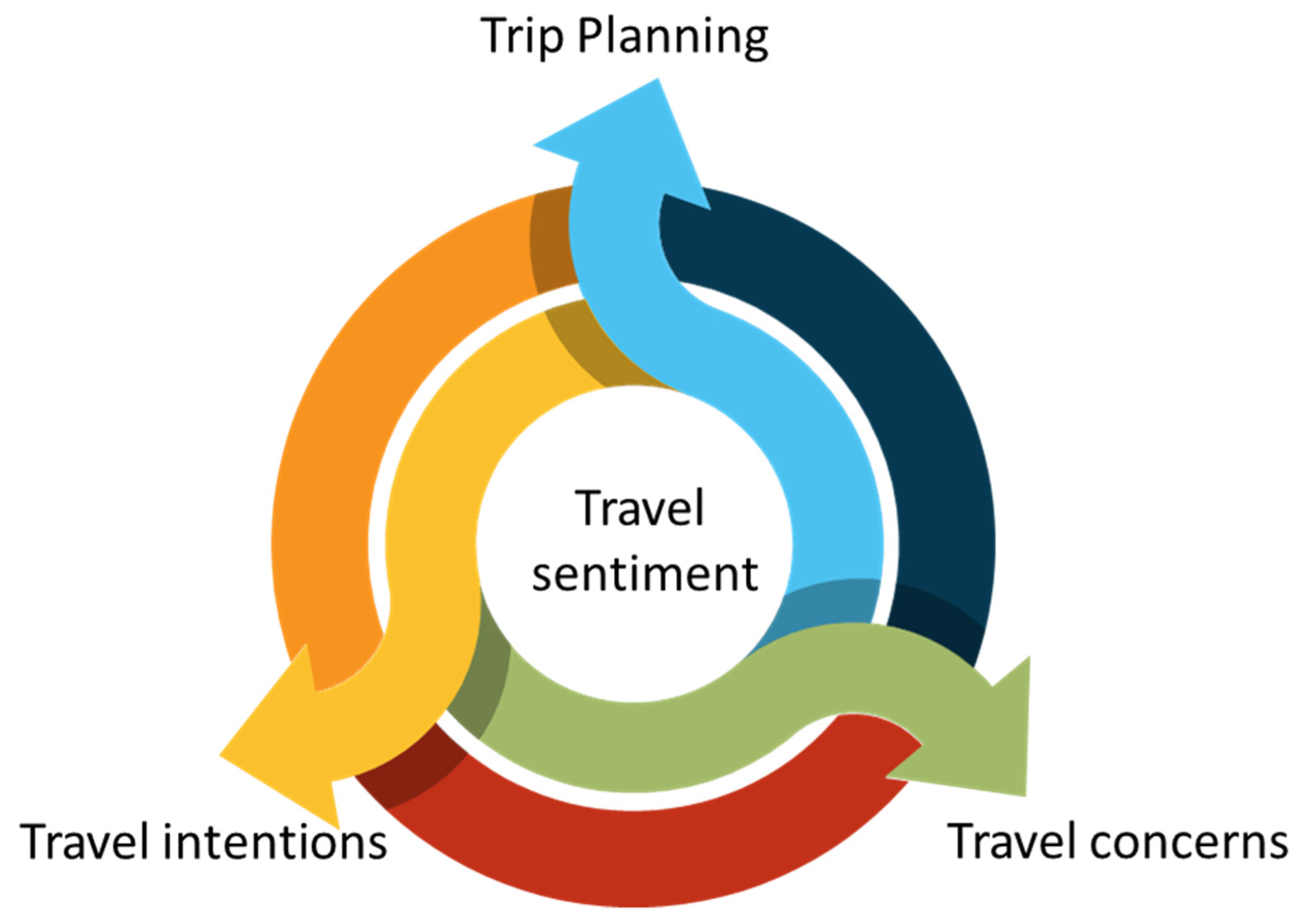

2.2. Travel Motivations and Travel Sentiment

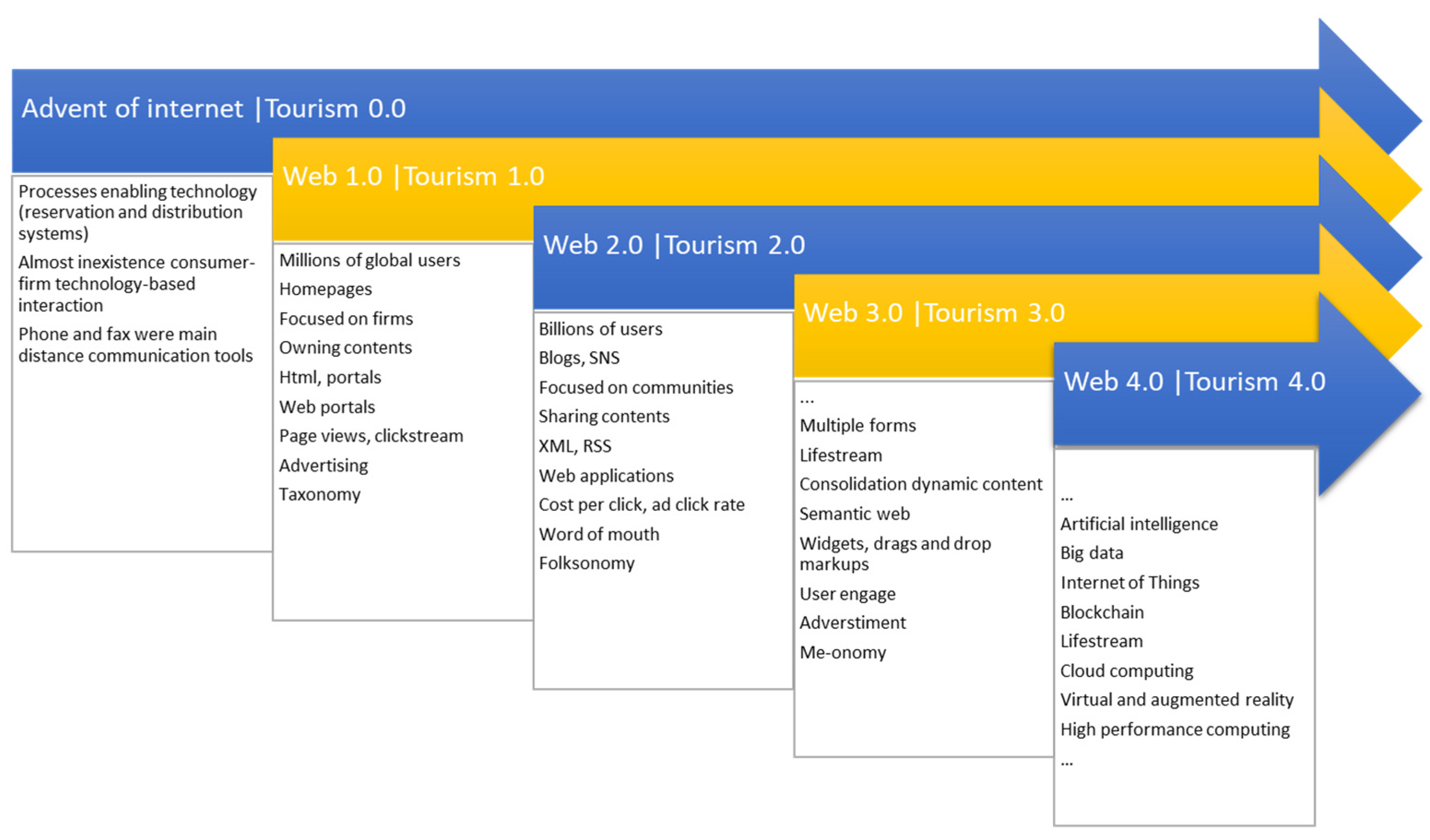

2.3. Tourism, Technology, and Digital Communication

- Planning a trip;

- Acknowledging the destination’s cultural and natural heritage;

- Finding more problematic activities or issues related to the trip; and

- Revealing the roots of the establishment of community relationships.

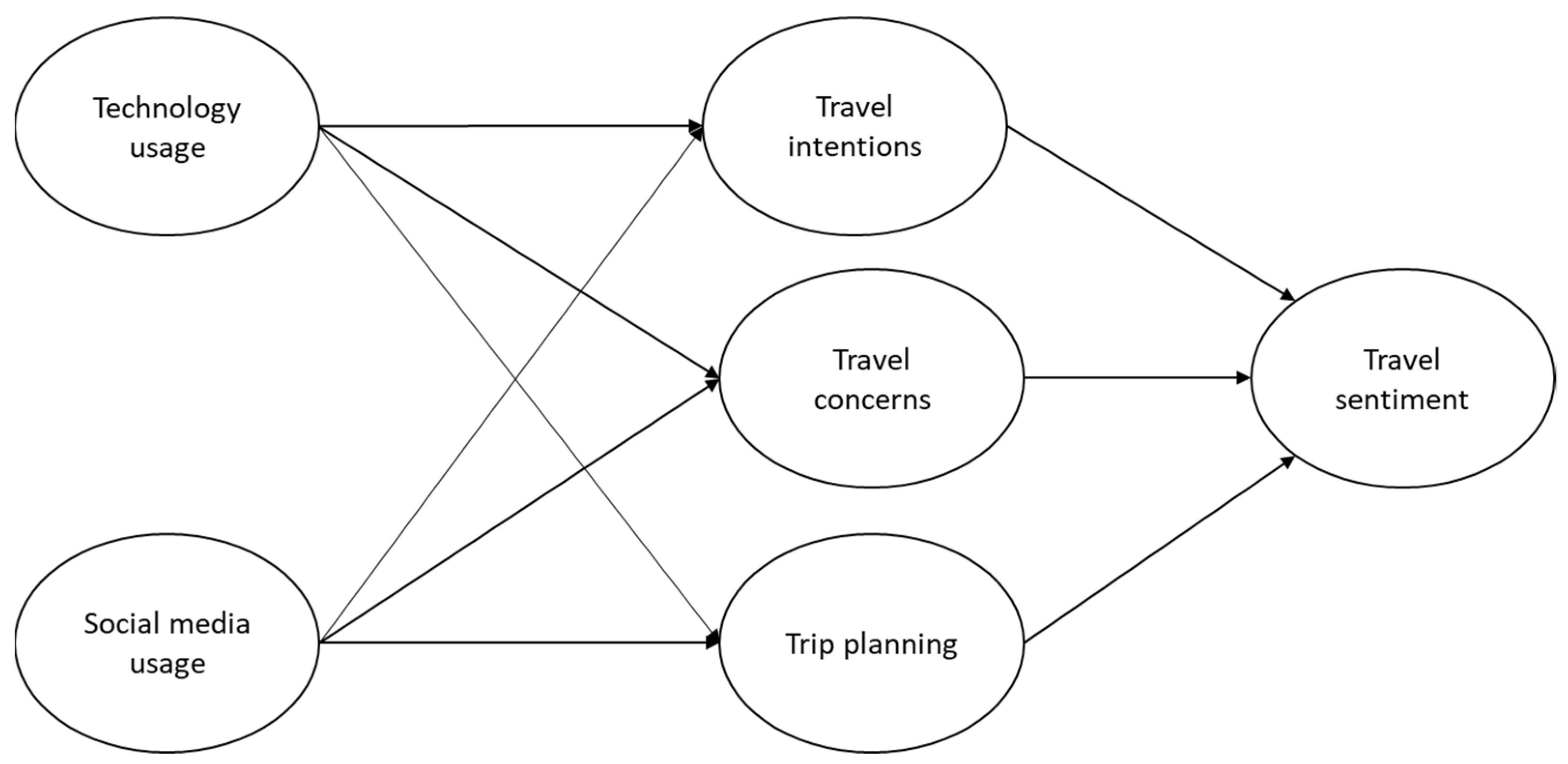

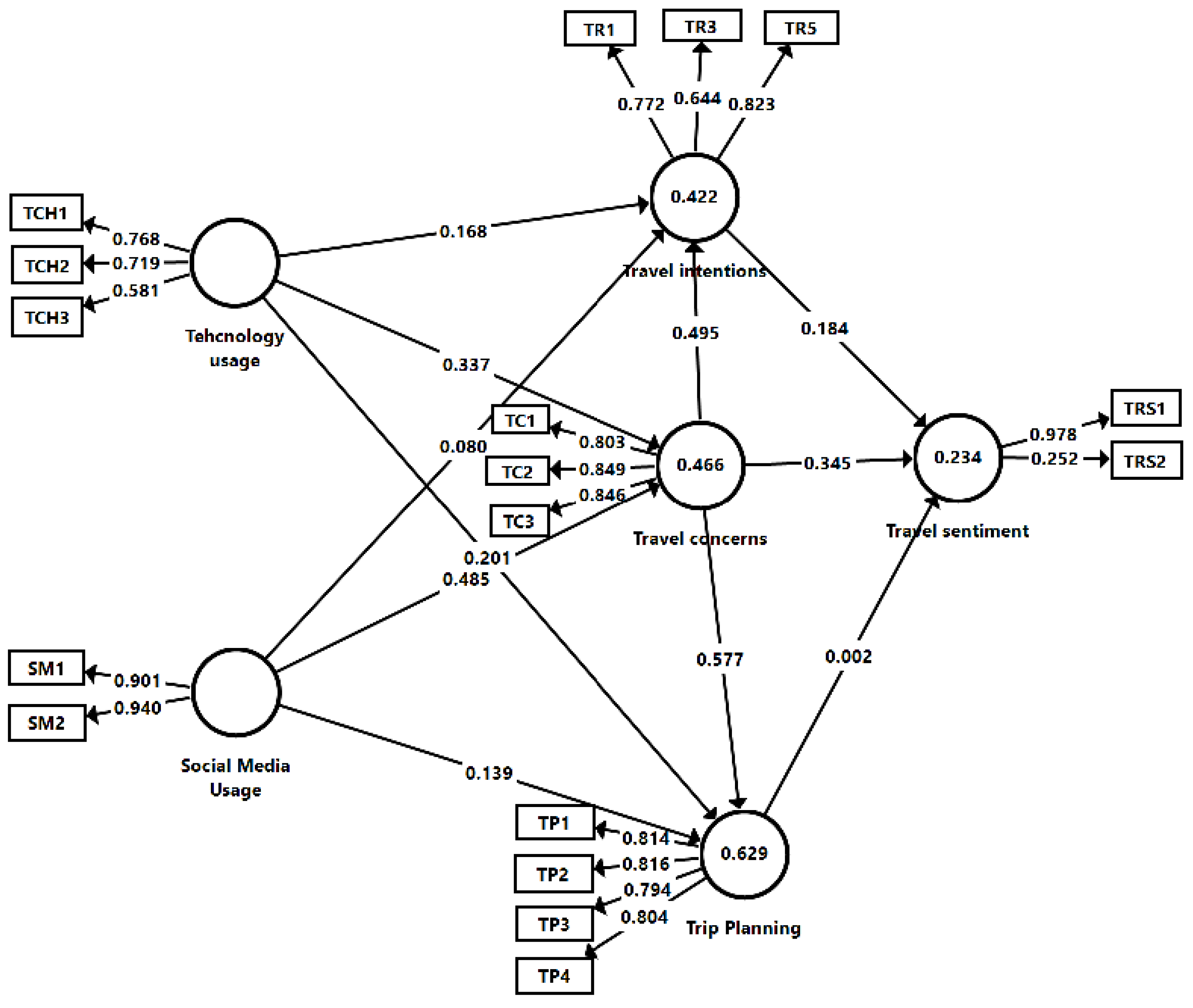

- RQ 1. Does social media usage positively impact travel intention and trip planning?

- RQ 2. Are there positive spillovers from the adoption of technology by the destination in terms of travel intention and travel concerns?

- RQ 3. How much do travel intentions, trip planning, and travel concerns influence tourists’ willingness to travel, coined from travel sentiment, post-COVID-19?

3. Method

- The research objective is to conduct exploratory research for theory development, considering less explored approaches;

- The pilot-sample size is small [69].

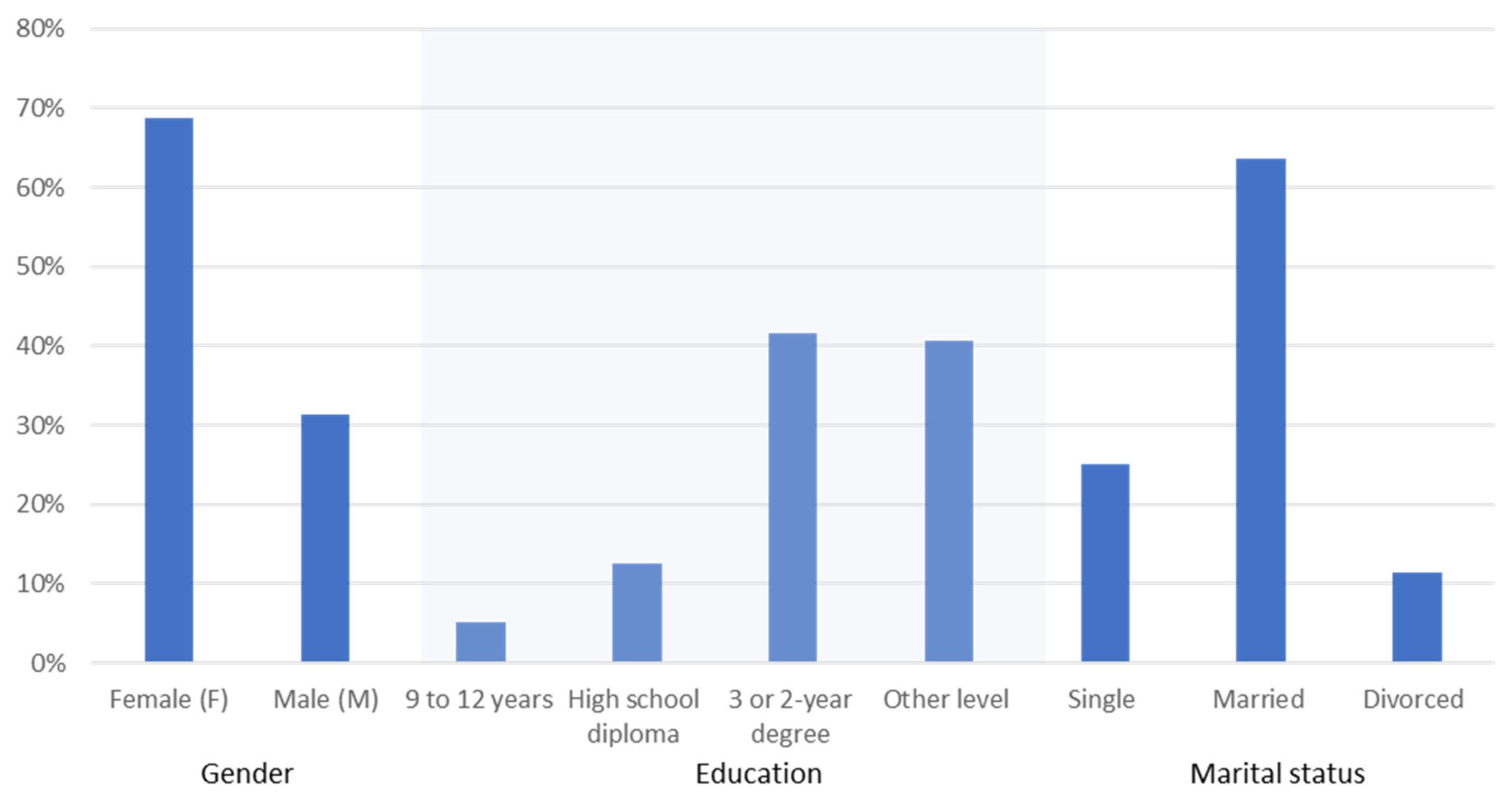

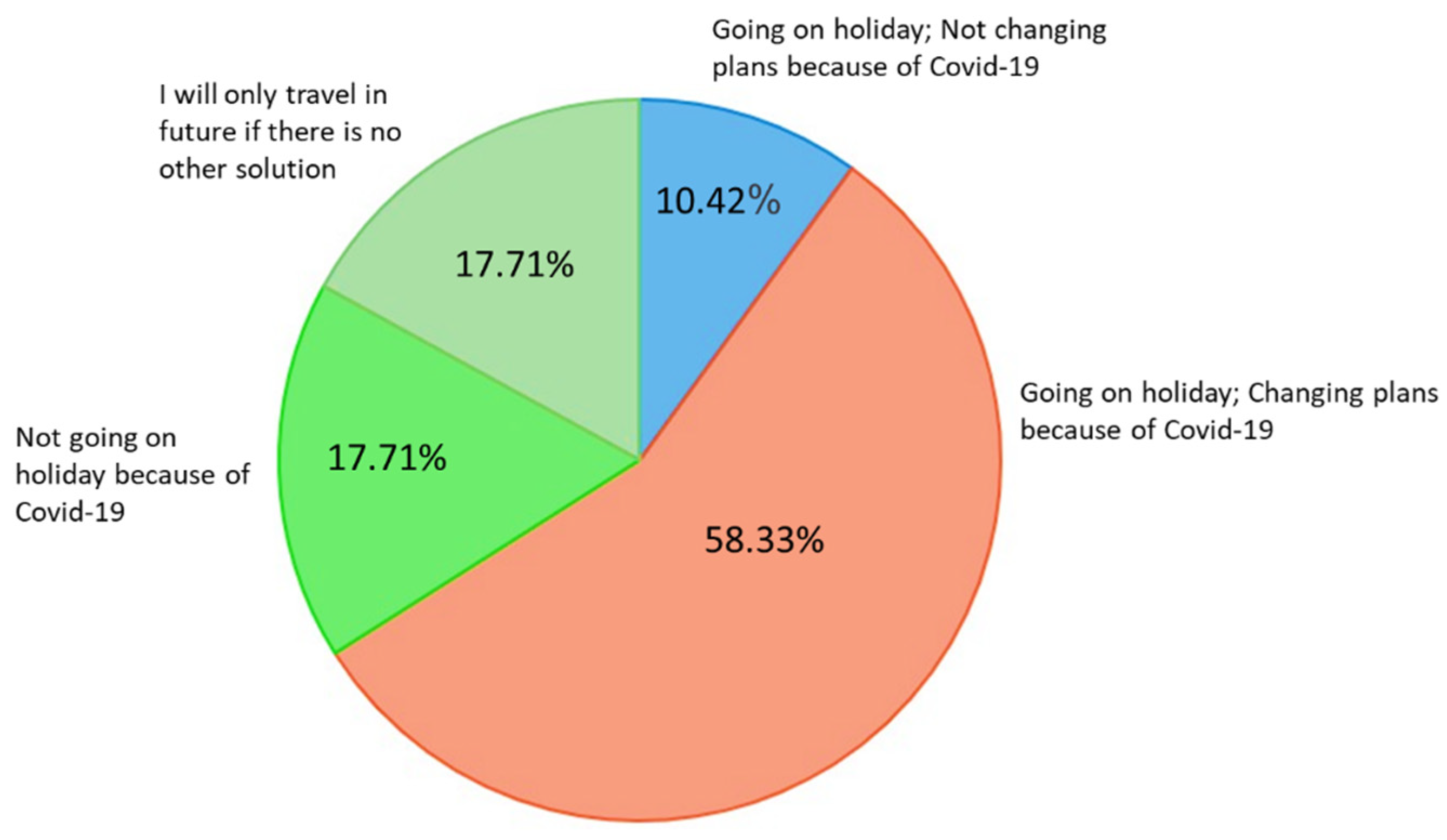

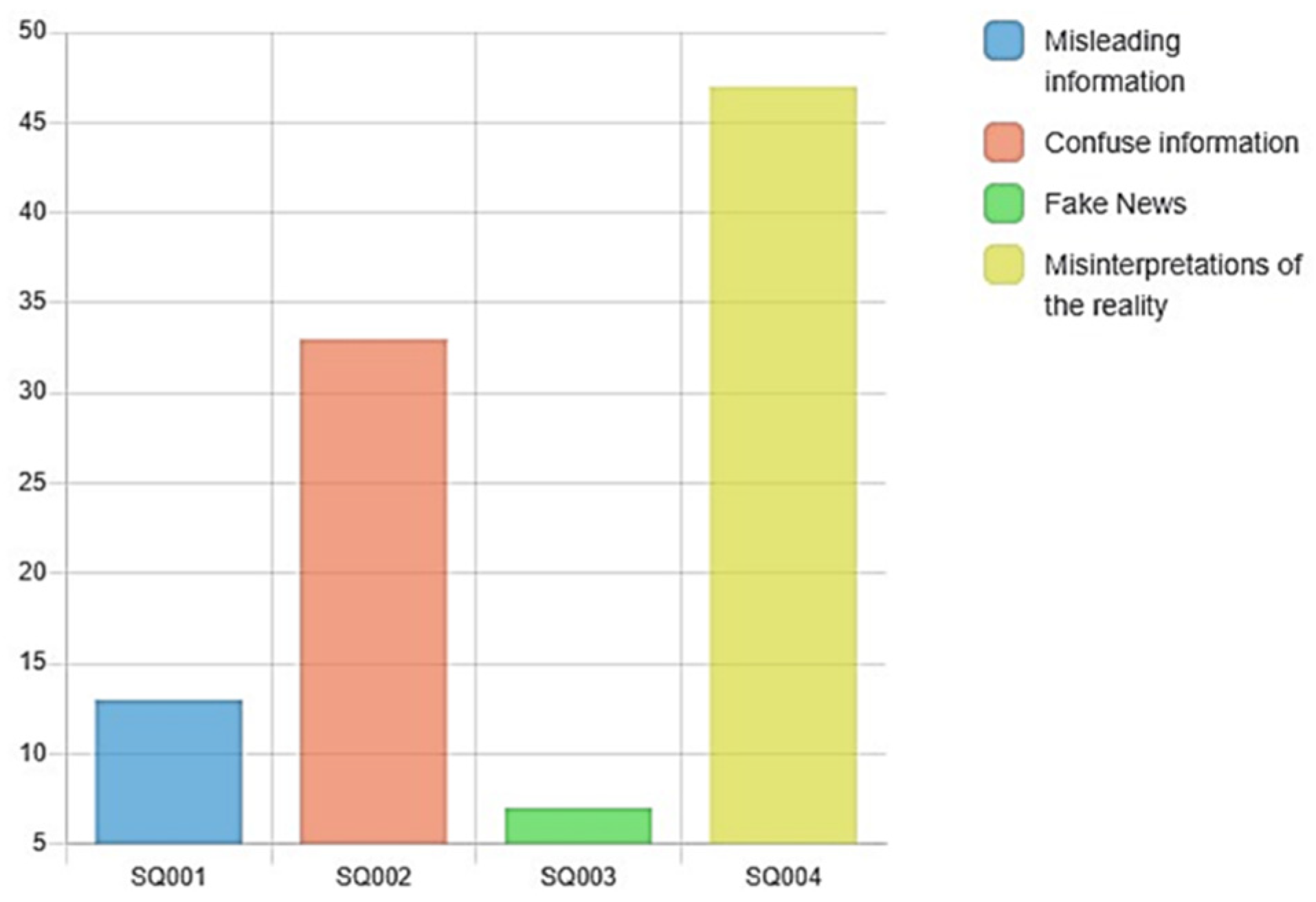

Survey Design and General Profile

- Socio-demographic characteristics;

- Traveling patterns before and post COVID-19;

- Reasons and concerns for going on holiday; and

- Technology and information sources.

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, E. How Hard Will the Coronavirus Hit the Travel Industry. National Geographic 2020. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/2020/04/how-coronavirus-is-impacting-the-travel-industry/ (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D. The role of resilience in research and planning in the tourism industry. Athens J. Tour. 2020, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.F.; Sousa, B.B.; Rocha, A.M.A.; de Abreu, Z.H.L. Education Excellence and Innovation Management: A 2025 Vision to Sustain Economic Development during Global Challenges; Communication Strategies to Combat the Negative Effects of Covid-19 on Tourism; International Business Information Management Association: Sevilla, Spain, 2020; pp. 10997–11005. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F.; Teichert, T.; Deng, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, G. Dealing with pandemics: An investigation of the effects of COVID-19 on customers’ evaluations of hospitality services. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.; Borges-Tiago, T.; Tiago, F.; Silva, S. Virtual Communities in COVID-19 Era: A Citizenship Perspective. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism in the COVID-19 Era, Proceedings of the 9th ICSIMAT Conference, Online, Greece, 2020; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arens, E. How COVID-19 Has Changed Social Media Engagement. Available online: https://sproutsocial.com/insights/covid19-social-media-changes/#volume-updates (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- Sheth, J. Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, P.K.; Kavoura, A.; Theodoridis, P.K.; Kavoura, A. The Impact of COVID-19 on Consumer Behaviour: The Case of Greece. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism in the COVID-19 Era, Proceedings of the 9th ICSIMAT Conference, Online, Greece, 2020; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.-S. Developing a Conceptual Model for the Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Changing Tourism Risk Perception. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Herhausen, D.; Ludwig, S.; Ordenes, F.V. The future of digital communication research: Considering dynamics and multimodality. J. Retail. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, T.L.; Winter, S.R.; Rice, S.; Ruskin, K.J.; Vaughn, A. Factors that predict passengers willingness to fly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susanto, I.; Kiswantoro, A. Tourism Branding: A Strategy of Regional Tourism Sustainability Post COVID-19 in Yogyakarta. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 704, 012003. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Dias, C.; Muley, D.; Shahin, M. Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on travel behavior and mode preferences. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamshiripour, A.; Rahimi, E.; Shabanpour, R.; Mohammadian, A.K. How is COVID-19 reshaping activity-travel behavior? Evidence from a comprehensive survey in Chicago. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 7, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, L.; Im, J.; Fu, X.; Kim, H.; Zhang, Y.E. Proximal and distal post-COVID travel behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahuddin, A.F.; Tergu, C.T.; Brollo, R.; Nanda, R.O. Post COVID-19 Pandemic International Travel: Does Risk Perception and Stress-Level Affect Future Travel Intention. J. Ilmu Sos. Ilmu Polit. 2020, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; He, J.; Zhou, J. Communication related health crisis on social media: A case of COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2699–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G. On the origin of tourist behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, S. Tourist behaviour and tourism motivation. Res. Themes Tour. 2011, 3, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Iso-Ahola, S.E. Towards a social psychology of recreational travel. Leis. Stud. 1983, 2, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebli, A.; Volgger, M.; Taplin, R. A two-dimensional approach to travel motivation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–16. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13683500.2021.1906631?casa_token=vuVBzysBpqgAAAAA%3A8aa6nG_j4mAmh6lK2BIy8gbiUkCud167xIbonIUlQ5hulmftFqk4h1jp7v0zU3k9Aeub_fp6bXczJA (accessed on 23 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Tourism Planning and Destination Marketing; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.J.; Chelliah, S.; Ahmed, S. Intention to visit India among potential travellers: Role of travel motivation, perceived travel risks, and travel constraints. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Pizam, A.; Bahja, F. Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Nicolau, J.L.; Kang, J.; Sharma, A.; Lee, H. Travel decision determinants during and after COVID-19: The role of tourist trust, travel constraints, and attitudinal factors. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.E.; Chen, L.H. Restarting travel in the era of COVID-19: Preparing anew. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningrum, D.A.; Wachyuni, S.S. The shifting trends in travelling after the COVID 19 pandemic. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Rev. 2020. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JTF-04-2020-0063/full/html?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=rss_journalLatest (accessed on 23 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T. Post-COVID-19 crisis travel behaviour: Towards mitigating the effects of perceived risk. J. Tour. Futures 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, C.; Joun, Y.; Han, H.; Chung, N. A structural model for destination travel intention as a media exposure Belief-desire-intention model perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1338–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachyuni, S.S.; Kusumaningrum, D.A. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic: How are the future tourist behavior? J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2020, 33, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Kirilenko, A.P. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Do tourists from different countries interpret travel experience with the same feeling? Sentiment analysis of TripAdvisor reviews; Springer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- PAVIĆ, Sandra. The Impact of COVID-19 on Technology in the Hotel Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, RIT, Dubrovnik, Zagreb, Croatia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, M.; Raghavan, V.; Abraham, D.; Kleist, V. Beyond utilitarian factors: User experience and travel company website successes. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 19, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyitoğlu, F.; Ivanov, S. Service robots as a tool for physical distancing in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1631–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakar, K.; Aykol, Ş. Understanding travellers’ reactions to robotic services: A multiple case study approach of robotic hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2020, 12, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencarelli, T. The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, U.; Gretzel, U. Tourism 4.0 technologies and tourist experiences: A human-centered design perspective. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Tiago, T.; Veríssimo, J.; Tiago, F. Smart tourism: A scientometric review (2008–2020). Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 30, 3006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.A.; Hopkins, D. Autonomous vehicles and the future of urban tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Gretzel, U.; Pesonen, J. Marketing robot services in hospitality and tourism: The role of anthropomorphism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthner, H.; Klein, S. Information Technology and Tourism: A Challenging Ralationship; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z. From digitization to the age of acceleration: On information technology and tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Smartphone use in everyday life and travel. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Park, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. The role of smartphones in mediating the touristic experience. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Law, R.; Chan, I.C.C.; Wang, L. A comprehensive review of mobile technology use in hospitality and tourism. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 626–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Fuchs, M.; Baggio, R.; Hoepken, W.; Law, R.; Neidhardt, J.; Pesonen, J.; Zanker, M.; Xiang, Z. e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A call for transformative research. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagler, A.; Hanus, M.D. Comparing virtual reality tourism to real-life experience: Effects of presence and engagement on attitude and enjoyment. Commun. Res. Rep. 2018, 35, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, A.O.; Koh, S.G. COVID-19 and extended reality (X.R.). Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1935–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, A.; Gonzalo, J. The Role of Augmented Reality in Destination Branding. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 26, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, O. To Recovery & Beyond: The Future of Travel & Tourism in the Wake of COVID-19; WTTC: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, M.; Ivanov, I.K.; Ivanov, S. Travel behaviour after the pandemic: The case of Bulgaria. Anatolia 2021, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiago, T.; Couto, J.P.; Tiago, F.; Faria, S.D. From comments to hashtags strategies: Enhancing cruise communication in Facebook and Twitter. Tourismos 2017, 12, 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tiago, T.; Veríssimo, J. Digital marketing and social media: Why bother? Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Tiago, M.T.; Arruda, C.; Tiago, F.; Rita, P. Differences between TripAdvisor and Booking.com in branding co-creation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotis, J.; Buhalis, D.; Rossides, N. Social Media Use and Impact during the Holiday Travel Planning Process; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Hofacker, C.F.; Bloching, B. Marketing the pinball way: Understanding how social media change the generation of value for consumers and companies. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoura, A.; Stavrianeas, A. The importance of social media on holiday visitors’ choices—The case of Athens, Greece. EuroMed J. Bus. 2015, 10, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Sinarta, Y. Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, B.; Karasek, A.; Zdonek, I. Social media usage by different generations as a tool for sustainable tourism marketing in society 5.0 idea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadis, M.D. Sharing tourism experiences in social media: A literature review and a set of suggested business strategies. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 179–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacSween, S.; Canziani, B. Travel booking intentions and information searching during COVID-19. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Park, S. When guests trust hosts for their words: Host description and trust in sharing economy. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, Z.; Ernszt, I. Omnipresent Social Media: Is Travelling Imaginable without Smart Devices? Manag. Glob. Transit. Int. Res. J. 2020, 18, 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 33, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajli, M.N. A study of the impact of social media on consumers. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 56, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Park, S. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Consumer evaluation of hotel service robots; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 308–320. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Factors | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Technology Usage (KMO—0.924) | Automation technologies | TCH1 |

| Robots and V/A reality | TCH2 | |

| Online booking | TCH3 | |

| Social Media Usage (KMO—0.885) | Searching | SM1 |

| Sharing and Socializing | SM2 | |

| Travel Intentions (KMO—0.915) | Present intentions | TR1 |

| Past intentions | TR3 | |

| Future intentions | TR5 | |

| Travel Concerns (KMO—0.926) | Travel | TC1 |

| Health and Safety | TC2 | |

| Financial | TC3 | |

| Trip Planning (KMO—0.935) | Destination characteristics (e.g., distance, location, sustainability strategy) | TP1 |

| Timeline and frequency | TP2 | |

| Health destination conditions | TP3 | |

| Reservation policies | TP4 | |

| Travel Sentiment (KMO—0.807) | Sentiment for domestic travel | TRS1 |

| Sentiment for international travel | TRS2 |

| Construct | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media Usage | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.92 |

| Technology Usage | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.82 |

| Travel Concerns | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.87 |

| Travel Intentions | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.82 |

| Travel Sentiment | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Trip Planning | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| Construct | SMU | TU | TC | TI | TS | TP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media Usage (SMU) | 0.92 | |||||

| Technology Usage (TU) | 0.55 | 0.73 | ||||

| Travel Concerns (TC) | 0.61 | 0.74 | 0.83 | |||

| Travel Intentions (TI) | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.70 | ||

| Travel Sentiment (TS) | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 1.00 | |

| Trip Planning (TP) | 0.56 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.38 | 0.81 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borges-Tiago, T.; Silva, S.; Avelar, S.; Couto, J.P.; Mendes-Filho, L.; Tiago, F. Tourism and COVID-19: The Show Must Go On. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212471

Borges-Tiago T, Silva S, Avelar S, Couto JP, Mendes-Filho L, Tiago F. Tourism and COVID-19: The Show Must Go On. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212471

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorges-Tiago, Teresa, Sandra Silva, Sónia Avelar, João Pedro Couto, Luíz Mendes-Filho, and Flávio Tiago. 2021. "Tourism and COVID-19: The Show Must Go On" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212471

APA StyleBorges-Tiago, T., Silva, S., Avelar, S., Couto, J. P., Mendes-Filho, L., & Tiago, F. (2021). Tourism and COVID-19: The Show Must Go On. Sustainability, 13(22), 12471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212471