Abstract

Ghana produces 20% of global cocoa output and is the second-largest producer and exporter of cocoa beans in the world. The Ghana cocoa industry is, however, challenged by a lack of adequate decision support systems across the supply chain. Particularly, cocoa farmers have limited access to information, which impedes planning, pricing, benchmarking, and quality management. In order to address this asymmetric access to information and ensure fair access to information that will allow the making of informed decisions, the supply chain stakeholders need to adapt their business processes. For identifying the requirements for better information flow, we identified the existing (as-is) processes through a systematic survey study in Ghana. We then identified the main problems and bottlenecks, designed new (to-be) business processes, and showed how IT systems support and enable inclusive business models in the Ghana cocoa industry. To enable inclusiveness, we incorporated IT solutions that improve information flows towards cocoa farmers. The results show that there are many opportunities (e.g., improving farmer livelihoods and a potential increase in export earnings) in the cocoa sector for Ghana and all stakeholders that can be utilized when there is chain-wide collaboration, equitable access to services, and proper use of IT systems.

1. Introduction

Cocoa is among the significant agroforestry crops grown across the globe. The crop is a key commodity in the agricultural sector of many producing and consuming countries, and its social and economic relevance can hardly be undervalued. It generates significant revenues, income, and employment for cocoa-producing countries [1].

Ghana’s cocoa industry contributes substantially to the global cocoa market. Ghana is the second-largest producer and exporter of cocoa beans globally and accounts for 20% of worldwide production [2,3]. The sector has a unique position in the country’s economy because of its social and economic impact. It has consistently been identified as the largest foreign exchange earner and currently accounts for over 30% of total export earnings and 4% of GDP [3,4,5]. The cocoa sector in Ghana provides a source of livelihood for 6.3 million people, representing 30% of the total population in the country [6,7,8,9]. Over 800,000 smallholder farmers and their families form part of the 30% of beneficiaries who depend on the sector for their living [6]. The cocoa sector is the key heartbeat of Ghana’s economy; therefore, any probable threat to the sector will bring social and economic downturn to the country. However, the sector is challenged by unequal access to services among the stakeholders in the supply chain [2,10,11].

The Ghana cocoa supply chain, like many agri-food supply chain networks, is complex. It is made up of stakeholders with varied business goals and objectives [11]. The stakeholders are responsible for completing the activities that stemmed from the production, transportation, and marketing of cocoa beans in the supply chain. Additionally, there is a seamless flow of money and services and materials such as seedlings, cocoa products, fertilizers, and chemicals such as fungicides in the cocoa supply chain. A study conducted by [2] identified the sharing of information as part of the major flows in the cocoa supply chain. Power in terms of access to information is skewed and limited in the Ghana cocoa supply chain [4,10]. In general, access to market (demand and price) and agronomic information in the supply chain are limited to a few dominant stakeholders, which impede the capacity of other stakeholders (mainly farmers) in their need for planning, pricing, benchmarking, and quality management [11]. This has restricted the extent of information flows and sharing among the cocoa supply chain stakeholders [4]. The majority of the stakeholders, who are farmers, are generally excluded from the information sharing process despite their key roles in the supply chain [4,7,10]. This makes it difficult for such stakeholders to make informed and optimal decisions in their business activities.

To address this asymmetric access to information and ensure fair access to information that will allow the making of informed decisions, the stakeholders across the supply chain need to adapt their business processes. This will enhance inclusiveness, which, in turn, will enable the flow of information towards the weakest stakeholders, especially smallholder cocoa farmers. In an inclusive business or supply chain, all stakeholders, particularly smallholder farmers, are given equal opportunities to participate in the decision processes of the supply chain and achieve their ultimate business goal [12,13,14]. A study conducted by UNDP [15] identified a lack of adequate information flow, particularly information on the weaker stakeholders, as the greatest obstacle to achieving inclusiveness in supply chains or businesses.

This paper aims to contribute to addressing this situation by proposing a framework that supports and guides the analysis and design of improved information sharing business processes for the Ghana cocoa supply chain. Specifically, the study focuses on building and testing a business process framework to analyze current processes and design to-be process models, respectively. To achieve this central objective of the present study, four research questions (RQ) have been formulated, which are:

- RQ1: How do we design a conceptual framework for analyzing and designing supply chain processes for supporting inclusiveness?

- RQ2: What are the current (as-is) supply chain systems of the cocoa supply chain?

- RQ3: How can this supply chain be analyzed to support inclusiveness? and

- RQ4: What are the new (to-be) business processes, and how can they be enhanced by IT systems to support inclusiveness in the cocoa supply chain?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, we introduce the case, i.e., the Ghana cocoa industry and cocoa supply chain. Next, Section 3 presents the research materials and methods used to achieve the objectives of the article. The designed supply chain inclusiveness framework is shown in Section 4. The framework was applied to the Ghana cocoa supply chain, and the results are presented in Section 5. The results derived from the research are also discussed in Section 6. Finally, the concluding remarks that include the lesson learned and suggestions for further research are detailed in Section 7.

2. Case: Ghana Cocoa Supply Chain

In Ghana, cocoa is produced in the forest areas of the country and is mostly found in the three agro-ecological zones, namely: rainforest, semi-deciduous forest, and transitional forest zones. Presently, the crop is grown in 6 out of the 16 regions in the country. These regions include both Western North and South regions, Brong-Ahafo, Central, Eastern, and Volta. The Western region is currently the main cocoa production area in Ghana, and production in this region is approximately 50% of total annual national production [2].

October is the cocoa-growing season in the Ghana cocoa industry, but the harvesting season is split into the main season, which is from October to May, and the light season, between June and September.

The current supply chain system of the cocoa industry has many actors, ranging from input suppliers to the farmers, traders, transport operators and other services providers, and, finally, to the domestic processors as well as the retailers [16]. These actors have a different role in the chain. These actors emanate from the different sectors (public, formal and informal) of the economy. A study conducted by [17] confirmed that the main stakeholders that oversee the processes in the cocoa industry are the cocoa farmers, LBCs, and COCOBOD.

COCOBOD is a government-owned organization that controls and oversees the general activities in the cocoa industry. COCOBOD supervises cocoa production and marketing in the country. The industry has a partially liberalized marketing structure, with some privatization elements and a strong government presence [2,18]. The partially liberalized marketing structure reforms started in 1991/1992 to allow the internal buying of cocoa from farmers by private participants. Despite the liberalization, COCOBOD still has a strong voice in the regulation of the cocoa supply chain, from quality checks to exports. For instance, the government, through the Producer Price Review Committee (PPRC) established by the government, regulates the price of cocoa.

In terms of domestic and international marketing, the Cocoa Marketing Company (CMC), a division under Ghana’s COCOBOD, is the only unit that controls the marketing of Ghana cocoa in the country and abroad. They do this with the support of the LBCs. Most of these LBCs are private-owned organizations that buy cocoa from farmers and sell it to CMC. The LBCs must be licensed by COCOBOD before they can purchase cocoa in the country. The LBCs purchase dried bagged cocoa beans from farmers with the help of their internal supply chain actors (purchasing clerks, district managers, port managers, and operations managers). The LBC then sells the dried cocoa beans to the CMC [19]. There are about 3000 locations, formerly called societies/buying centers in Ghana, where the LBCs can buy cocoa beans from the farmers [6]. The cocoa farmers, on the other hand, are in the frontline of the Ghana cocoa supply chain. They oversee farm production and pre-harvest activities in the cocoa sector. The smallholder cocoa farmers are the initiators and backbone of the cocoa supply chain because of their all-year-round production, and millions of Ghanaians depend on them for their income.

In terms of resources, the stakeholders in the cocoa supply chain utilize IT and paper-based systems to support the underlying business processes highlighted in the previous paragraphs. The downstream stakeholders such as COCOBOD and the traders formerly called LBCs have implemented IT systems to help manage their business processes [20]. In the same study, it was evident that the cocoa farmers, on the other hand, currently use a paper-based system, popularly called the farmer passbook, to support their production and marketing processes. However, access to and use of IT systems is still low and not evenly distributed among stakeholders in the cocoa supply chain. For instance, cocoa farmers in Ghana do not generally use modern ICT systems [20].

Besides the IT systems, the flow of materials, finance, and information form part of the activities that happen in the cocoa supply chain. In our present cocoa supply chain case, the type of information that is normally exchanged among some key stakeholders includes knowledge transfer, market information (demand and prices), and research data. The Ghana cocoa industry has been characterized to have centralized information architecture. COCOBOD collects and stores most of the information gathered from the stakeholders in the supply chain [2,7,20]. The information flows in the supply chain are not bi-directional. The cocoa farmers, for instance, provide data about farm production systems and practices, produce, quality, storage, and trade transactions to downstream stakeholders (either directly or through certification schemes). The stakeholders downstream of the supply chain increasingly extract valuable decision-making information from this data using analytical techniques. The farmers who are the source of these data do not generally receive basic information that enables them to benchmark themselves or obtain market price, input, and production information to make informed decisions about production and marketing [4,10]. The case of cocoa farmers illustrates the lack of inclusiveness in information sharing and, thus, the limitation in optimal decision-making in the cocoa supply chain.

The cocoa supply chain case has been described in the previous paragraphs. The description indicates that the Ghana cocoa supply chain is made of a supply chain system that manages the processes. Unequal collaboration and coordination of business processes in terms of information sharing make it difficult for the stakeholders to perform their supply chain function and plan strategically. Inadequate and low utilization of IT systems in the cocoa supply also affects the sharing of information and the inclusion of stakeholders into the different stages of the cocoa supply chain.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design Framework

We combined three widely used frameworks in this research, namely, Lambert and Cooper’s supply chain management framework [21], the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model (developed by Supply Chain Council) [22], and the LINK model to address the requirements for inclusiveness. The frameworks are used as a reference for the definition of the basic requirements of the proposed inclusive framework.

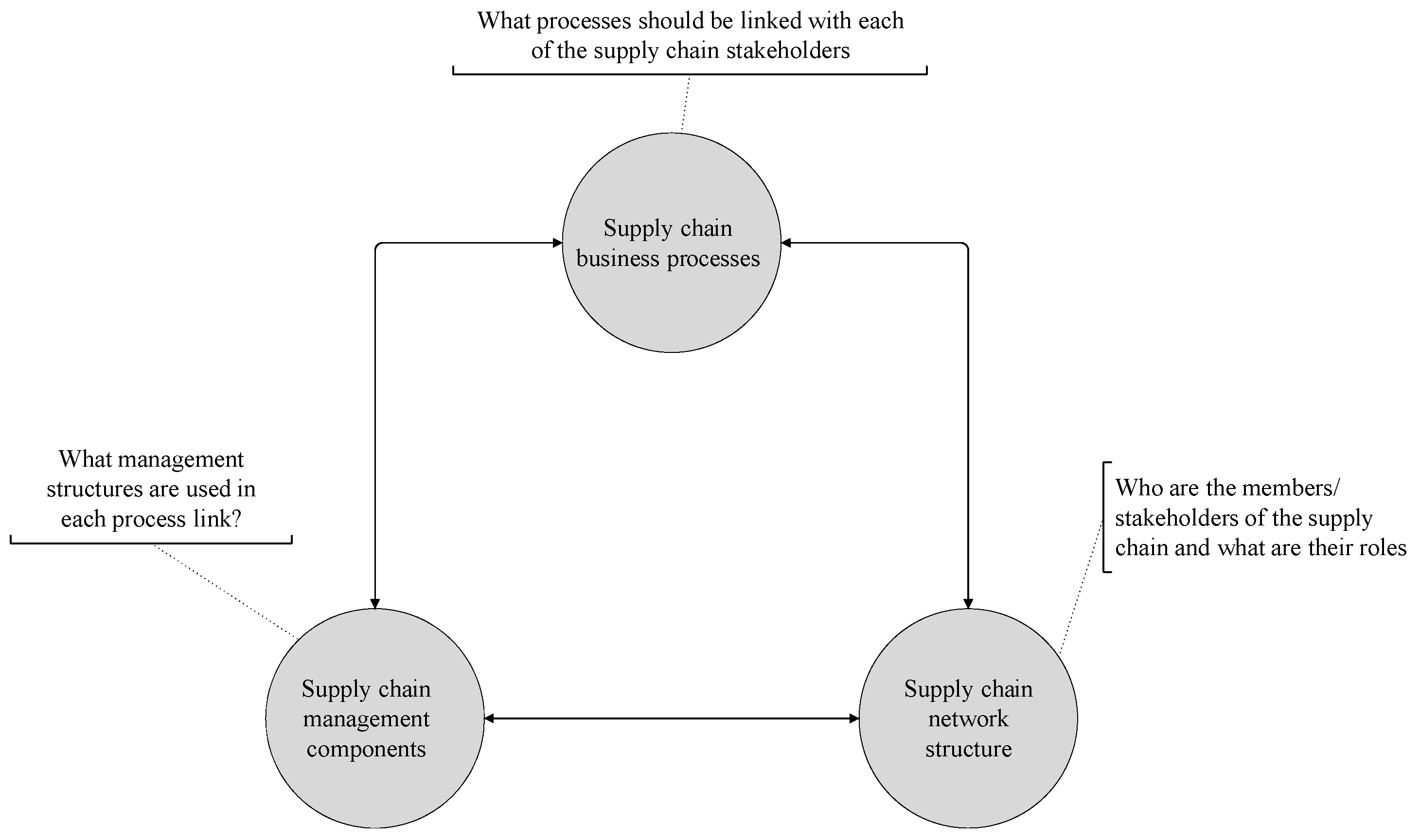

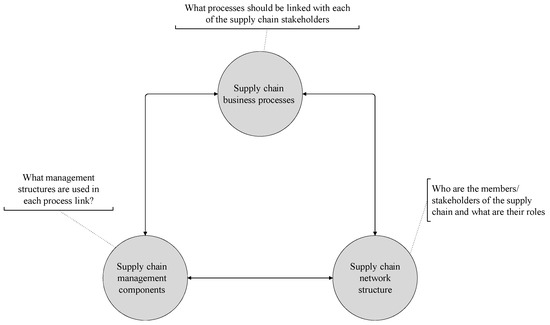

The framework of Lambert and Cooper [21] emphasizes the network structure of the supply chain and the fundamental steps or guidelines required to design and manage a supply chain. It has been applied extensively in the context of many agri-food supply chains (see, e.g., [23]). The framework contains three important interrelated elements and decision components (Figure 1): the supply chain network structure, supply chain business processes, and supply chain management components.

Figure 1.

Supply chain management framework: element and key decisions [21].

- Supply chain network structure: This depicts the network of main cooperating stakeholders who are participating in the supply chain, the structural dimension (institutional arrangement) of the supply chain, and the different process links between the stakeholders in the chain.

- Supply chain business processes: These define the structure of business activities that are designed and performed by the process stakeholders to produce a specific output. The output produced as a result of the business process can be in the form of physical products, financial services, and information.

- Supply chain management components: This element highlights the governance and control structures in the supply chain network. The governance structure revolves around the allocation of decision rights among the stakeholders participating in the supply chain. The controlling function provides an overview of the coordination, planning, and monitoring of the process performed by the stakeholders and how these processes fall within the governance structure.

The widely accepted SCOR model has been applied extensively in many sectors, particularly production [24], construction [25], and agriculture [26]. It provides reference processes, metrics, and best practices to allow organizations to manage, benchmark, and improve their supply chain practices and processes. The ideas can be management practices and software solutions [27]. The present paper adopts the SCOR reference processes as a basis for business process modeling and selects the best practices that can be used to improve supply chain inclusiveness.

The LINK model, which has been applied to many agri-food supply chain cases, contains principles and criteria for assessing supply chain inclusiveness. It helps facilitate the supply chain process to ensure that all key stakeholders are engaged in the coordination and collaboration process. We use this framework to evaluate whether a particular chain network is inclusive or not. The analysis is based on six principles, and these have been described briefly (Table 1). In our framework, we have used the principles and criteria of the LINK framework [28] to define specific guidelines for identifying, analyzing, and modeling business processes for inclusive supply chains.

Table 1.

Inclusive supply chain principles, based on the LINK framework [28].

3.2. Research Design

To answer the research questions, we used two major research methods. The first is design-based research, which used the results from a literature review to design a conceptual supply chain framework. As part of design research, formal business process models are produced. The second method is a survey case study based on semi-structured interviews from cocoa supply chain actors. The activities for the research design have been summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Steps for the research design.

3.2.1. Design Inclusive Supply Chain Framework

The design phase started with a narrative literature review in the Scopus database and Google Scholar on the Ghana cocoa industry, supply chain management, supply chain inclusiveness, and existing supply chain frameworks. The output of this was used for the definition of the basic requirements for the proposed framework. The information gathered on the existing supply chain frameworks was referenced. Next, the framework design started with the investigation of existing frameworks for inclusiveness analysis and supply chain design. As the baseline for our design, we selected three frameworks of sufficient detail, each of which addresses parts of the requirements (see Section 3.1 for details).

3.2.2. Survey Study Based on Semi-Structured Interviews

A case study was conducted in the Ghana cocoa supply chain to help address research questions RQ2, RQ3, and RQ4. The study used an interview-based discovery method (see [29,30]) to gather data on the current supply chain systems in the cocoa industry. Using this strategy helps the researchers to administer questionnaires to collect vital information that is accurate and useful from respondents. Within the survey study design approach, four different steps were followed:

- We first used the purposive sampling technique to sample 56 key process participants (stakeholders) from the Ghana cocoa supply chain. The 56 process participants included 20 cocoa farmers, 33 officials from LBCs, and three COCOBOD CMC officials. The decision for purposively selecting these key process participants was based on their fundamental roles and end-to-end understanding of the cocoa supply chain system.

- After the sampling process, semi-semi-structured paper questionnaires were designed. The paper questionnaires, which contain a pre-defined set of closed and open-ended questions, were divided into sections: questions about the process participants, descriptions of the current business process (as-is), the envisioned business process (to-be), and the current (as-is) and envisioned IT systems (Table A1, Appendix A).

- The questionnaires were then finally administered to the participants, and responses from the participants were recorded directly on the paper questionnaires.

- The raw data on the paper questionnaires were digitized onto Microsoft Office Excel 2016 after the interviews. Important information concerning the process participants, their roles in the supply chain, events, activities, decision points, and interactions (flows) between process participants and activities were categorized and listed in an Excel tabular form.

3.2.3. Model the As-Is Supply Chain Systems

The interview results were used to apply the designed framework to the Ghana cocoa supply chain case. RQ2, which aims to present the as-is process models of the cocoa supply chain, is illustrated using guidelines from the proposed framework. The as-is processes were modeled using the business processes of the key process participants, as identified from the interview results. This was done using the business process modeling approach, as highlighted by [30]. The business process of the participants was translated into standard process models using the formalized software Business Process Modeling Notation (BPMN) v2.0 [31,32]. This was presented for the complete cocoa supply chain system and separately for the process participants, which include cocoa farmers, LBCs, and the COCOBOD CMC. For each of the process participants, the supply chain network and the business process, including the boundaries of the process, activities, events, and the handovers of the process, are presented. Modeling the processes gave a clear snapshot (understanding, visualization, and documenting) of the processes in the Ghana cocoa supply chain and made it easier for the inclusive analysis. The results of the modeling of the as-is supply chain are in the “Existing supply chain systems (as-is) in the Ghana cocoa industry” (Section 5.1).

3.2.4. Analyzing As-Is Supply Chain Systems

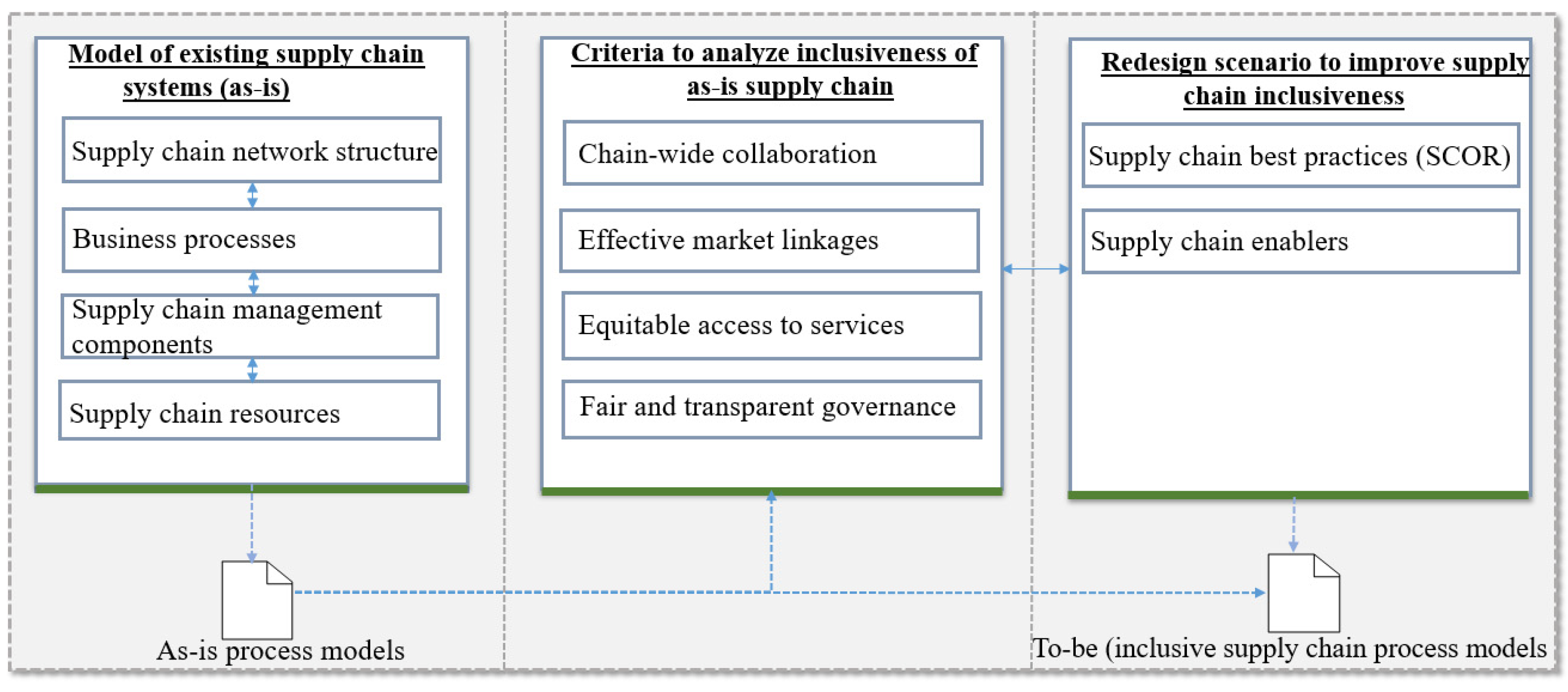

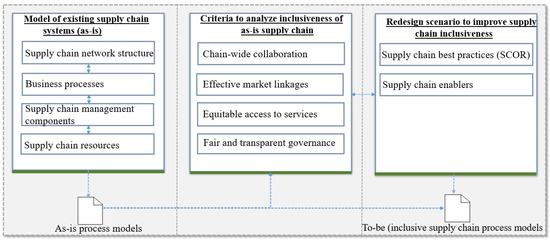

After the modeling of the as-is business processes, we performed an analysis of the stakeholders’ current processes to assess the inclusiveness of the cocoa supply chain (RQ3). This activity was done by applying the supply chain inclusiveness criteria and the principles of the designed framework (Figure 2 and Table 2). This activity resulted in a list of scores for the scoring criteria, and the outcome is available in the “Analysis of the inclusiveness of the as-is supply chain systems” section.

Figure 2.

The designed inclusive supply chain framework.

3.2.5. Modeling and Evaluating To-Be Supply Chain Systems

The modeling of the to-be system started with a redesign scenario based on SCOR best practices and related processes (RQ4). The to-be scenario was modeled for the complete cocoa supply chain. This scenario was modeled using the same process modeling approach as the as-is models (Section 3.2.3). During the redesign, we also considered how the existing IT systems of the process participants could be fully utilized, and our expert opinions were considered as well. This is because the researchers who worked on the present article have over a decade of practical experience with agri-food supply chain redesign and information systems implementation. The to-be model was evaluated using the designed framework requirements and the expert opinions of the researchers. The to-be designed model is available in the Section 5.3.

4. Model Building: Design of Inclusive Supply Chain Framework

4.1. Definition of Inclusiveness of Requirements

The main purpose of conceptual framework design (RQ1) is to assist in the analysis and design of an inclusive supply chain. Based on this study’s objective and the analysis of current supply chain frameworks (Section 3.1), the inclusiveness requirements for our framework can be formulated as follows:

The framework must

- R1: support the modeling of the as-is processes in the supply chain;

- R2: help to identify role-players or stakeholders in the supply chain;

- R3: support the analysis of a supply chain to enhance inclusiveness;

- R4: provide insight into the best practices or redesign scenarios for addressing supply chain issues; and

- R5: contribute to a better understanding of the governance structure in the supply chain.

The frameworks (Section 3.1) contain elements that fulfill the basic requirements (R1–R4), but their intended use and focus are different from the objective of this study. None of the analyzed frameworks explicitly provide the complete components for analyzing and designing a supply chain for enhancing inclusiveness. It is thus important to have one framework to analyze and design supply chain inclusiveness. In Section 4, we have presented our designed framework as part of the study goal.

4.2. Business Process Framework for Inclusive Supply Chains

Addressing the inadequate information flow issue in the Ghana cocoa supply chain with IT systems to improve inclusiveness requires adequate understanding and redesign of the current business processes. Hereby, the supply chain design process comprises the mapping and analyzing of business processes and the (re)design of the supply chain network. The article adopts the elements in the existing frameworks from the literature to propose our conceptual framework. Our proposed inclusive supply chain framework was used to analyze and design a cocoa supply chain for inclusiveness. The objects in the framework show different components, and the relationships between them are depicted with arrows. To fulfil the identified basic requirements, the designed framework comprises three key parts (Figure 2):

- Model of existing supply chain systems (as-is);

- Criteria to analyze the inclusiveness of the as-is supply chain; and

- Redesign scenarios to improve supply chain inclusiveness (to-be).

4.3. Model of Existing Supply Chains (As-Is)

The designed inclusive supply chain framework in Figure 2 starts with the modeling of existing supply chain systems (as-is). This part further contains subcomponents: supply chain network structure, business processes, supply chain management components, and supply chain resources (Figure 2). This part is based on the framework of [21] and is referred to as supply chain systems, but we have applied it with some adaptations. The highlights below summarize the elements in this component.

- Supply chain network structure: This element describes the organizational units, stakeholders, and actors that perform the execution of the business processes in the supply chain.

- Business processes: These depict the activities (financial, material, and information) performed by the process participants at different stages in the supply chain. Business processes in the supply chain can be in the form of events, decisions, or interactions (flows) between the participants in the supply chain.

- Supply chain management components: These define the governance structure in the supply chain. The management component also extends to the control mechanisms found in the supply chain.

- Supply chain resources: Resources in the supply chain show the enablers or capabilities that facilitate the movement of the product from one stage to the other. Supply chain network resources can be in the form of IT systems or human resources. The resource element was missed in the framework of [21]; for the focus of this study, it is thus important to understand these resources, particularly the IT systems used by each of the stakeholders in the Ghana cocoa supply chain, in order to support the underlying business processes.

Using the above elements provides guidelines and insights to identify the business activities of the stakeholders, which, in turn, guide the translation of the processes to the formalized as-is process models.

4.4. Criteria to Analyze the Inclusiveness of the As-Is Supply Chain

This is the second part of the framework (Figure 2); it focuses on the analysis of the as-is process models using our adapted LINK framework criteria and principles. For the designed framework and the purpose of the study, we applied four out of the six elements: chain-wide collaboration, effective market linkages, equitable access to services, and fair and transparent governance (Figure 2).

A supply chain is considered inclusive if the supply chain checks or scores positively to all the criteria related to the identified principles or elements [28]. Table 3 presents the list of the chosen criteria and their respective scoring criteria used for analyzing an inclusive supply chain. Using this scorecard involves subjecting the supply chain system to each of the criteria and grading them on a five-point quality scale (1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = basic, 4 = good, and 5 = very good). It is also possible to combine expert opinions in the scoring process. It is important to score or grade each criterion; this implies that each criterion should either have a positive or negative response. Any of the criteria with a score below 3 implies that the criterion does not apply at all. A score above 3 means the criterion fully applies to the supply chain. For example, a score of 2 for the criterion stakeholders exchange information regularly means the stakeholders in the supply chain do not share supply chain information frequently. To get the average score, the scores for each principle are then summed up. The average is taken to then arrive at a final average score, which will lead to a conclusion about the state of inclusiveness of the supply chain for the criterion in question [28]. The analysis results for each principle and criterion aid in the identification of the targets areas for the redesign process.

Table 3.

Chosen evaluation principles and their related criteria.

4.5. Redesign Scenarios to Improve Supply Chain Inclusiveness (To-Be)

This is the final part of the designed framework. This element involves the enhancement of the as-is supply chain system to meet the desired objective of the supply chain [22]. The redesigned part builds on the as-is process by utilizing the analysis results of the existing processes to support the design of to-be models (Figure 2). For the designed framework, we focused on applying the SCOR best practices (outlined in version 12 of the SCOR model [33]) to solve criteria with the lowest marks (scores less than 3). SCOR practices could relate to the automation of the process, application of technology or special skills to the process, or a unique sequencing for performing the process. The SCOR model has over 500 leading general best practices, organized at SCOR level 3, for managing supply chain processes [22]. Each of these practices is linked to a business process.

For this framework and the present research purpose, we apply the guidelines highlighted by [34] for selecting the best practices. The authors stated that factors such as existing scenarios and practices in the supply chain, situations, and priority problems must be considered when selecting SCOR best practices. Some of the best practices relevant for this study were selected (Table 4), and these were used as the redesign scenario and requirements for the to-be model. The SCOR reference model defined each best practice and process. It is beyond the scope of this paper to include these definitions, but, for illustration purposes, Table A2 Appendix B shows Best Practice 183 Integrated Business Planning.

Table 4.

Linking scoring criteria to SCOR best practices (redesign scenario) and business processes.

Each best practice is linked to scoring criteria and enablers (capability), and this is mapped to the subcomponents listed under Part One of the designed framework. The mapping between the best practice and the scoring criteria is important because it will provide the right information to select the target criteria or process area for the redesign.

5. Model Testing: Application of the Inclusive Framework to the Ghana Cocoa Supply Chain

5.1. Existing Supply Chain Systems (As-Is) in the Ghana Cocoa Industry

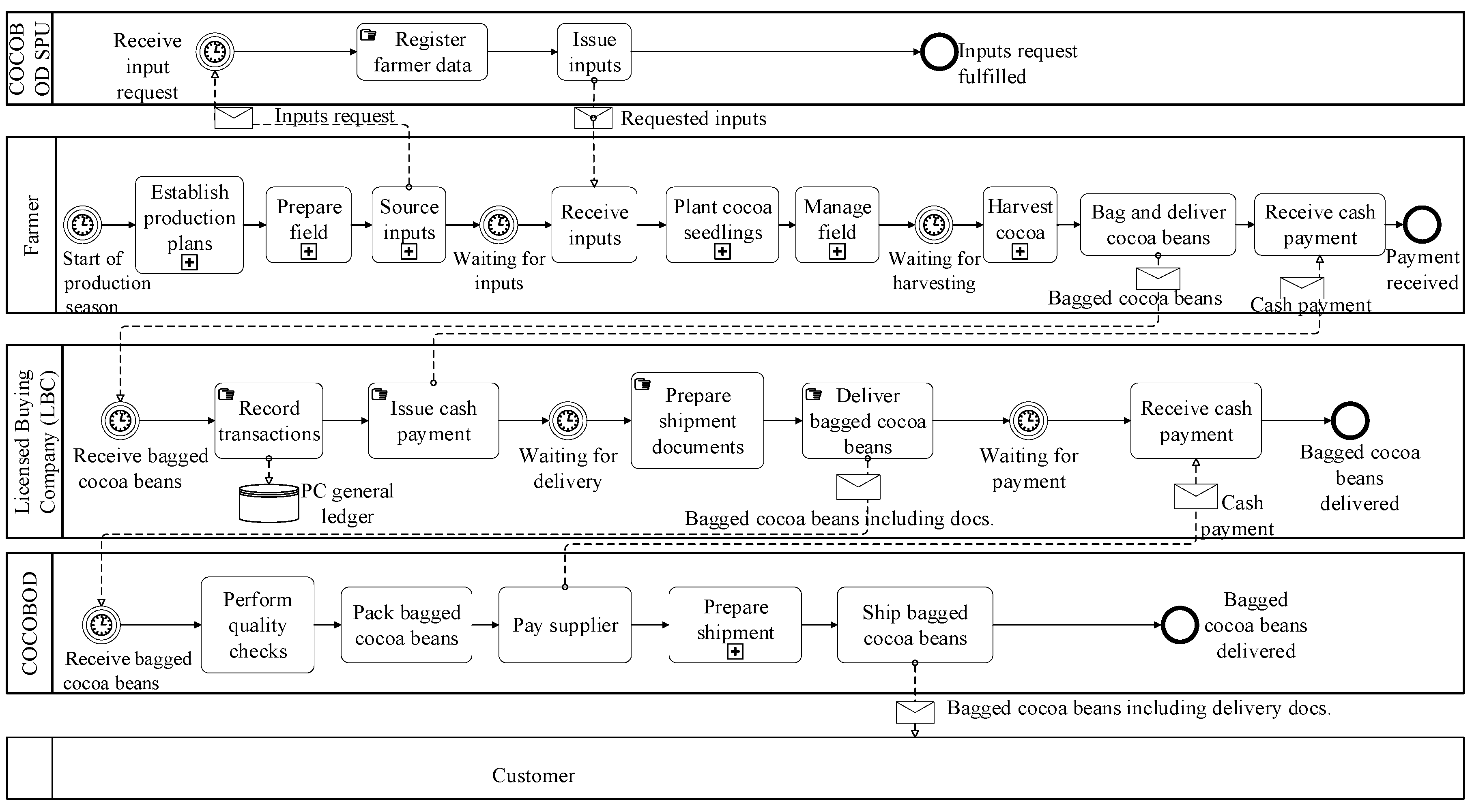

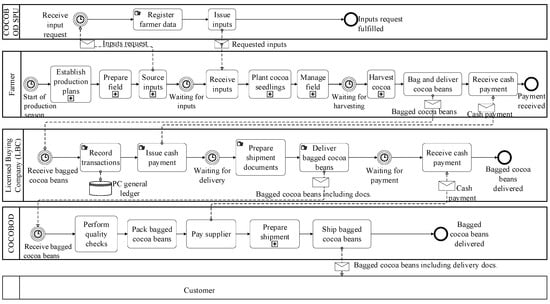

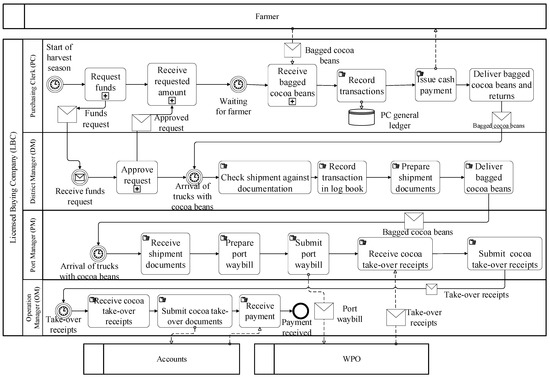

This subsection presents the results of RQ2, which aim to illustrate the current supply chain systems of the stakeholders in the cocoa supply chain. The case study shows that the different elements of the framework are very useful for modeling the existing supply chains in the Ghana cocoa industry. Figure 3 shows a high-level overview of the as-is process model of the applied framework. In addition, Appendix C includes a more detailed diagram and description of the supply chain actors in this scope.

Figure 3.

The overall process model for the Ghana cocoa supply chain.

The existing cocoa supply chain is systematically defined using the elements of the framework:

- Supply chain network structure: The study identified cocoa farmers, cocoa traders or buying companies (LBCs), and COCOBOD CMC as the main process participants or stakeholders in the Ghana cocoa industry. COCOBOD CMC is the marketing wing of COCOBOD. We found that the cocoa farmers are direct stakeholders in the cocoa supply chain. They oversee field management, harvesting, and postharvest handling of business activities in the supply chain. The LBCs act as indirect stakeholders as they facilitate the buying of dried cocoa beans from farmers and the selling of the dried cocoa beans to the COCOBOD CMC. COCOBOD, on the other hand, is the administrative regulator and implementer of policies in the cocoa industry. It oversees the economic and legal/political factors that affect the stakeholders in the cocoa supply chain. This result aligns with the study conducted by [2,17].

- Business processes: The interview results revealed the main business processes performed by the process participants in the cocoa supply chain to include: sourcing of inputs (input procurements), production, purchasing of dried cocoa beans, and the warehousing and marketing of cocoa beans. In terms of process flow, the results of the research reveal that the cocoa farmer (Figure 3) initiates the overall business processes. The domestic activities within the complete business process end when the received cocoa beans pass the quality checks and payment is settled between the buying company and COCOBOD CMC. The business process of COCOBOD customers, which is out of the scope of the study, is represented with a blank pool or black box (Figure 3). The process shows that the smallholder farmer has less interaction with the other stakeholders in the cocoa supply chain.

- Supply chain management components: We found that all the planning, controlling, and monitoring functions in the overall cocoa supply chain are performed by COCOBOD. It is the main decision body in the cocoa supply chain. Moreover, the study reveals that the actors in the cocoa supply chain operate under the Make-To-Stock (MTS) production policy. This implies that the processes in the Ghana cocoa industry are performed based on forecasting measures.

- Supply chain resources: In terms of resources in the form of IT systems, each of the different stakeholders uses different systems. The results indicate that cocoa farmers, for instance, use paper-based systems and mobile phones to perform their business activities whilst the buying companies and COCOBOD CMC have in-house-built IT systems such as field and port management systems, accounting systems, and enterprise resources planning (ERP) systems. The ERP systems for COCOBOD, for instance, contain subsystems for handling and managing their warehouse and ports operations.

5.2. Analysis of the Inclusiveness of the as-Is Supply Chain System

5.2.1. Chain-Wide Collaboration

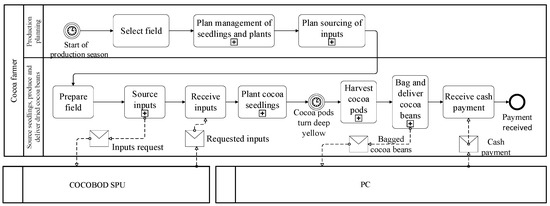

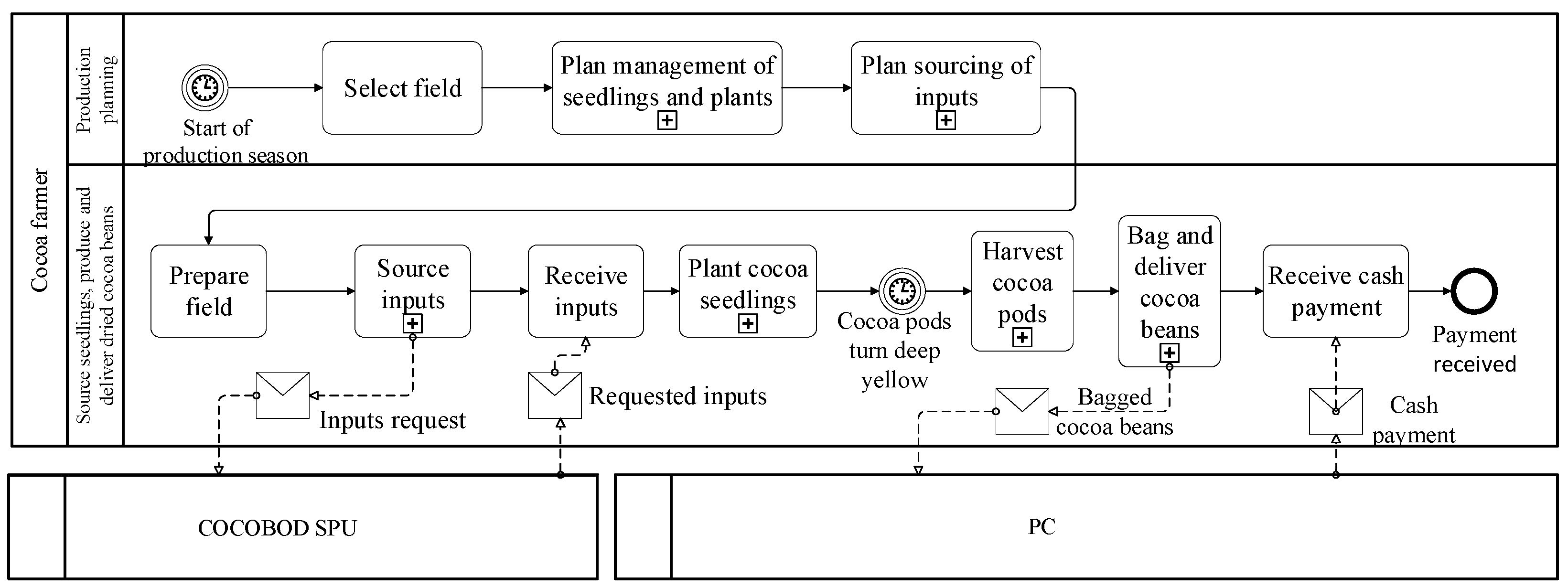

The results of RQ3 are presented in this section. The inclusiveness analysis for the complete cocoa supply chain confirmed very poor chain-wide collaboration among the stakeholders in the Ghana cocoa industry (Table 5). An average score of 2.0 (Table 5) for chain-wide collaboration shows that there is no formal collaboration between upstream and downstream stakeholders. The cocoa farmer business process model (Figure A1, Appendix C), for instance, reveals that the farmer interacts with the COCOBOD SPU (when requesting inputs of seedlings and pods) and LBC purchasing agents (when selling bagged cocoa beans). Aside from this interaction, the business process of the cocoa farmer does not reveal any additional interaction between the cocoa farmer and the industry regulator.

Table 5.

Scorecard showing scoring criteria and scores.

Uniform scores of 2 were recorded for each of the scoring criteria under the chain-wide collaboration principle (Table 5). The score of 2 for the criterion stakeholders exchange information regularly indicates that there is a huge information-sharing gap between the process participants in the cocoa supply chain. During the interviews, the respondents were asked to select from a list of supply chain management issues that hinder supply chain collaboration. The results reveal difficulty in interacting with members in the chain as one of the most obstructing issues in the cocoa supply chain. The respondents reveal that getting information from other stakeholders is difficult in the cocoa sector. The cocoa farmer, as part of his marketing activity with the PC, shares purchase information such as date of sale of cocoa beans, cocoa beans quantity sold (kg), cocoa beans sold (bags), district name, and society name, but the farmer has no idea of how such information is managed. These results of inadequate information sharing in the complete cocoa supply chain network have been reported in other studies [2,10,11,19]. This is consistent with the score of 2 assigned to the stakeholders exchange information regularly criterion.

From the study, it is also evident that the goals of the process participants are not aligned. There is no global objective that the stakeholders strive to achieve. COCOBOD, for instance, strives to achieve the strategic sourcing of cocoa, which might be different from the goal LBCs or farmers aim to achieve. This affects supply chain inclusiveness because a decision made by each stakeholder may affect other stakeholders’ decisions.

The poor chain-wide collaboration can be attributed to the lack of proper partnerships and collaborative structures between the supply chain members. The lack of inadequate IT and collaborative planning systems to establish the communication of supply chain plans among the process participants forms part of the causes of poor collaboration in the cocoa sector. The utilization of IT systems might help the stakeholders to devise effective communication and a global supply chain goal to improve the cocoa supply chain. Currently, most of the interaction activities among the process participants are done manually, and this, therefore, makes it difficult to promote regular collaboration among the stakeholders.

5.2.2. Effective Market Linkages

A moderate overall average score was recorded for the effective market linkages principle. This score is attributed to the lack of market information in the supply chain (Table 5). There is a sign of market information asymmetry; the downstream stakeholders tend to have more insights and knowledge concerning the cocoa market than the cocoa farmers. It can be deduced from the complete process model (Figure 3) that the cocoa farmer has no idea about the final consumer of his or her produce. The downstream stakeholders also have less information about the production systems of the farmer, as reported by [16]. This makes the trading relationship among the stakeholders unstable. The results of 1 and 3 for the criteria farmers know where their product is consumed and existence of trading relationship among stakeholders fall in line with the results of [4,11].

5.2.3. Equitable Access to Services

The inclusiveness analysis results concerning equitable access to services reveal that equal access to services in the cocoa supply chain is poor and inadequate (see the average score in Table 5). The flow of supply chain information, for instance, is unequal. Information flows only from upstream to downstream. The LBCs, as part of their business processes, share data concerning their purchases from the farmer with COCOBOD but do not receive anything in return. This does not enhance better collaboration in the cocoa supply chain. The supply chain stakeholders do not have timely access to information to inform their supply chain plan. This observation is linked to poor data and information management in the cocoa supply chain. This triggered and inspired the poor score of 2 for the timely access to market information by all stakeholders criterion.

Again, with the key role of the farmers in the chain, everyone expects them to receive regular financial and technical support from the survey; this is not the case. It also emerged that the farmers, who initiate the whole cocoa supply chain, have limited and poor access to financial support, technical support, and training when it comes to their production activities. This and other highlights from the complete supply chain form the basis of the scores for access to financial and technical support services by stakeholders and farmers have adequate access to training.

5.2.4. Fair and Transparent Governance

The overall basic average score from the scorecard (Table 5) shows that there are moderate standard rules about price setting, payment terms, and buying conditions in the Ghana cocoa sector. We found that sales and purchase prices differ among stakeholders. Though COCOBOD has set a standard price per bag of cocoa beans, some buying companies also have different price settings when buying the cocoa beans from the farmers. Because of this, the farmer can decide where he or she wants to sell his or her cocoa beans, and this makes them vulnerable to cheating, as reported in the study of [19]. The prices for sales and purchases of cocoa are not communicated regularly and clearly in the supply chain (see Table 5 for the results of sales/purchases prices are communicated clearly). This is a result of a lack of a better management system and supply chain structure to establish and facilitate this process.

We also found that there are limited or no formal contractual agreements relating to the trading partnership among stakeholders, particularly farmers and LBCs, thus a score of 3 for trading relationships are based on formal contracts. Again, quality standard measures are not clear among the stakeholders in the chain. Though COCOBOD enforces quality checks of the cocoa beans, some stakeholders, particularly the LBCs, have also implemented their own internal mechanisms to manage the quality of their purchases. These disconnected arrangements affect the equitable process in the supply chain. Currently, this approach enhances good quality standards in the cocoa supply chain, but inclusiveness in the supply chain would be better off if all stakeholders agreed to adopt a global quality management policy. This will help reduce the differences in the quality of management levels in the cocoa industry.

5.3. Business Process Redesign (To-Be) for an Inclusive Supply Chain

The results of the to-be process are illustrated in this section. The analysis shows that there is a lack of proper chain-wide collaboration, effective market linkages, and equitable access to services. To address these concerns, a framework is used to redesign the supply chain. The redesign objective is to enhance inclusiveness in the supply chain via effective collaboration and information sharing.

From the results of the as-is analysis, we selected the criteria with the lowest score for the redesign. As stated by [35], it is not advisable to redesign a complete process simultaneously. In Table 6, we have presented the scoring criteria with the lowest scores (score less than 3) for each principle. In addition, the related redesign scenarios using SCOR best practices and business processes for the best practices are presented. We also matched these columns with the values of supply chain system subcomponents (supply chain network, supply chain resources, and supply chain management components).

Table 6.

Recommended redesign scenarios and included supply chain system components to be changed.

Based on the SCOR best practices, business processes, and resources (Table 6), we elicited the following as the main requirements and capabilities for the to-be scenario. The to-be supply chain system must:

- RT1: contribute to integrated supply chain planning;

- RT2: give process participants mobile access to information;

- RT3: support information and data management (e.g., sales, purchases) in the supply chain;

- RT4: help stakeholders to be able to do strategic sourcing;

- RT5: contribute to better visibility in the supply chain;

- RT6: assist the full utilization of IT systems by all the stakeholders in the supply chain; and

- RT7: provide an avenue for vendor collaboration.

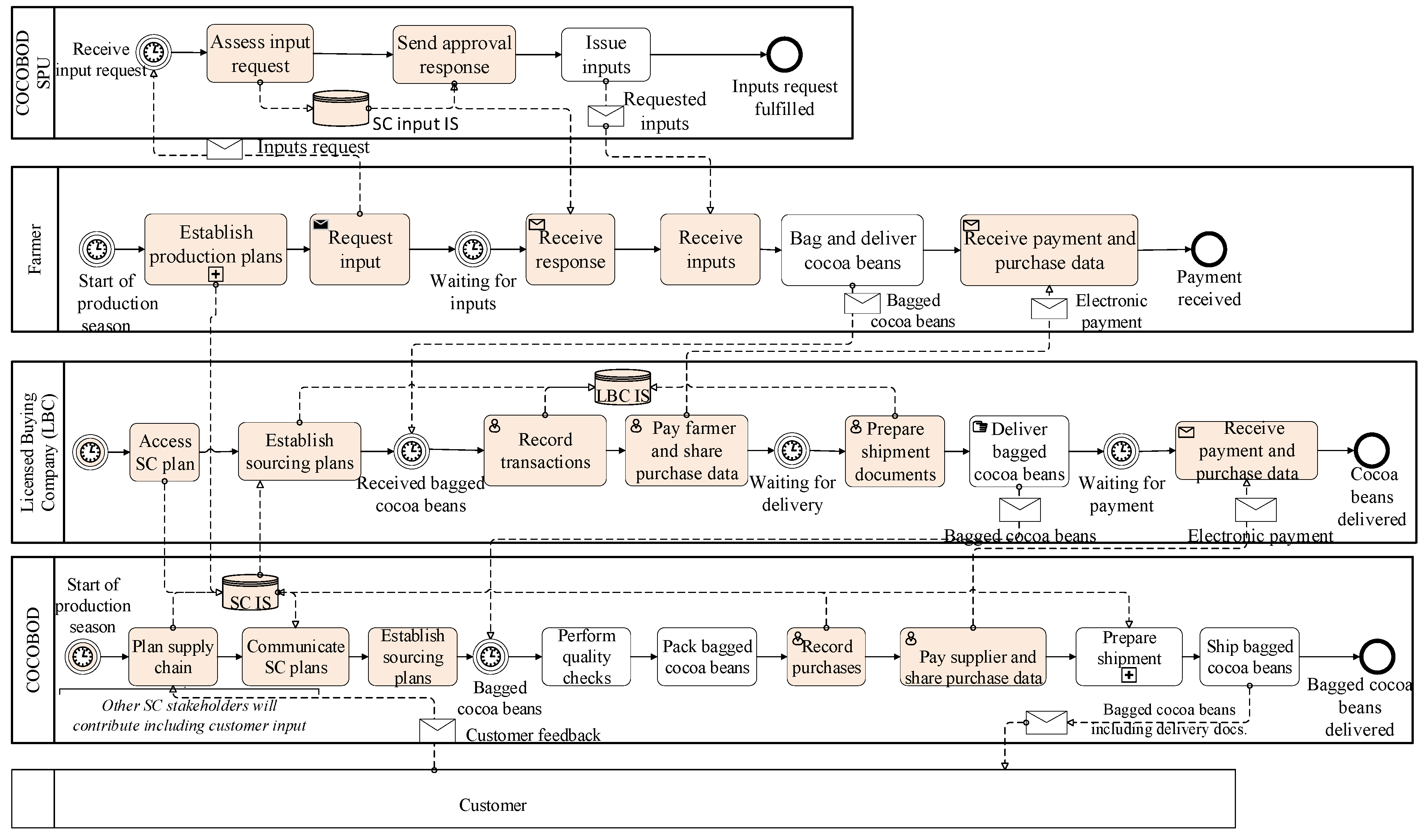

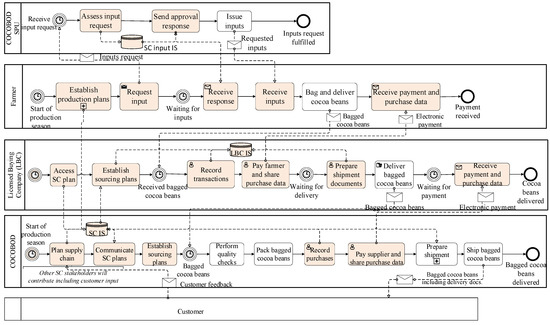

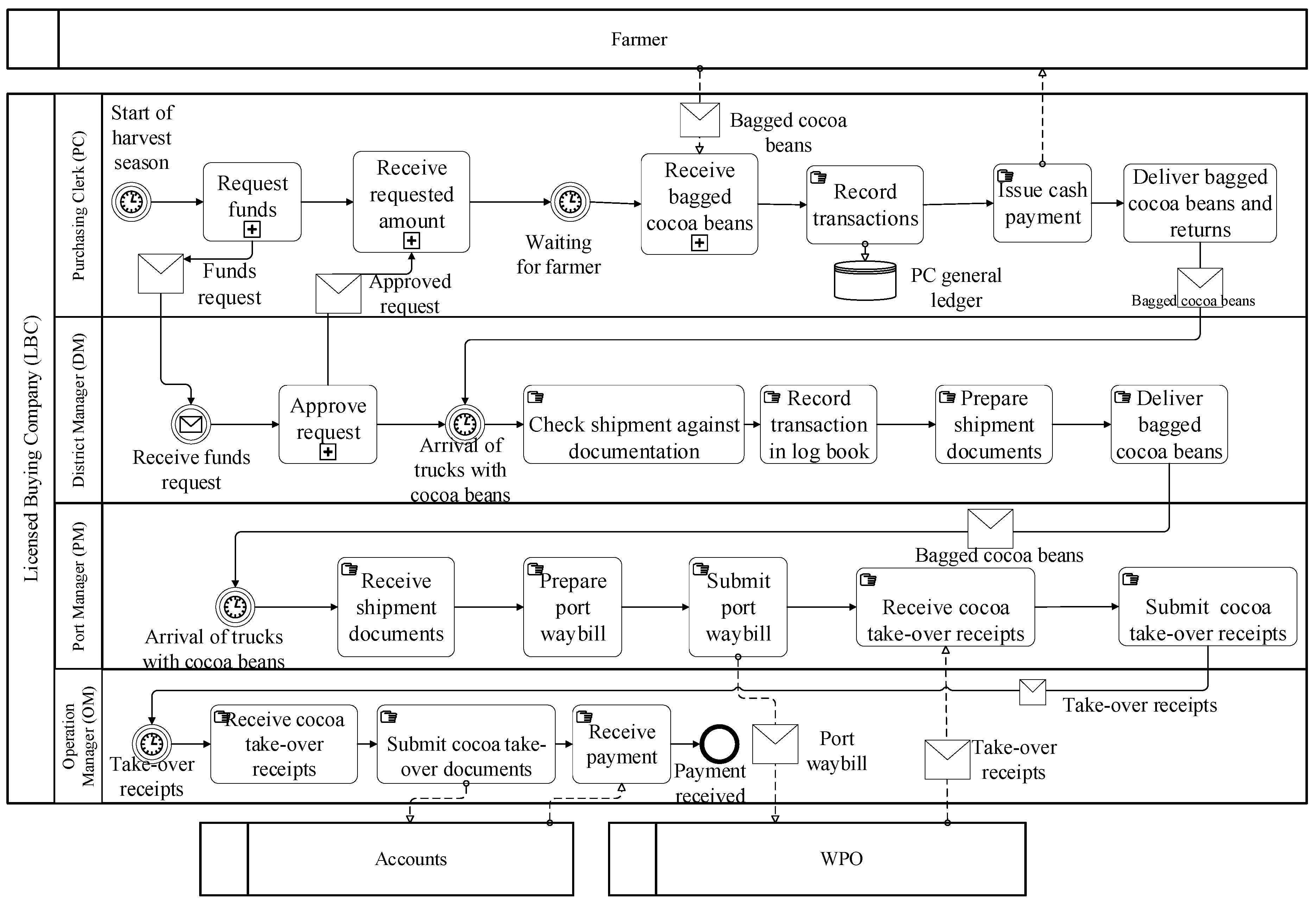

Figure 4 depicts the business activities of the to-be scenario.

Figure 4.

Overall inclusive supply chain process model (to-be) with IT needs.

The redesign (to-be) results using the supply chain system component reveal the following:

- Supply chain network structure: The organizational structure of the to-be scenario is the same as the as-is scenario, with cocoa farmers, cocoa traders or buying companies (LBCs), and COCOBOD CMC as the main stakeholders (no change,Table 6). The role played by each of these main stakeholders will also be the same as their roles in the as-is scenario. The difference in network structure between the as-is and the to-be scenarios is that there is a better coordination mechanism facilitated by IT systems in the proposed situation (to-be). This characterizes the to-be situation to be inclusive, with effective information flow and exchange, equitable access to services, and better chain-wide collaboration.

- Business processes: To reduce complexity and simplify the to-be processes, the to-be process model mainly highlights the flow of the product (bagged cocoa beans and inputs), information, and finance. The newly added process steps are filled with a light orange color. The to-be process will also be initiated at the start of the cocoa production season. In the to-be situation, this initiation will be done by COCOBOD in collaboration with the other stakeholders (farmers, LBCs, and customers). COCOBOD will lead the integrated supply chain planning, especially production and marketing, using the input data from the stakeholders. This process is represented as the supply chain plan (Figure 4). The supply chain plan will be stored in the proposed supply chain information system (SC IS; see Figure 4). This system, which will be managed by COCOBOD, will be accessible by stakeholders depending on their role and permission to access the system. COCOBOD, which is the industry regulator, will be mandated to communicate the supply chain plans to the supply chain members. This has been visualized as communicate SC plans in the process model (Figure 4). This scenario will help to fulfill the integrated supply chain planning requirement (RT1). The processes for the different stakeholders include the following:

- In the to-be model, the cocoa farmer will be able to access the supply chain information system (SC IS) to plan their production activities. This can be done via a basic mobile application interface or any relevant electronic medium. This will help the farmer to have better insight into market demand and other useful data needed to make production decisions and to benchmark. With the proposed situation, cocoa farmers, instead of requesting production input manually, can now request input electronically (see request input in Figure 4). The COCOBOD SPU will get a notification on the new input request. The SPU can easily assess and approve the input request, and the approval response will be sent to the requester to enable him or her to go for the input. These process steps have been shown in the cocoa farmer and COCOBOD SPU lanes of the process model (Figure 4). The software for requesting input can also be enhanced to have some functionalities where cocoa farmers can message the SPU for advice relating to farm maintenance and other issues that are deemed important. This will help the farmer to get regular information that is reliable and has an element of timely accessibility. The as-is model has been adapted to include an additional step (receive payment and purchase data), where cocoa farmers, after delivering their bagged cocoa beans to the PC, can now receive electronic payments instead of cash. The PC will also share purchase data electronically with the farmer to enable the farmer to have well-managed transaction data for his farming business. This will give the farmer a summarized view of his transactions for a particular period. Enhancing the as-is process with the aforementioned scenarios will contribute to inclusion in the cocoa supply chain. The farmer will have better information and data management and mobile and timely access to supply chain information. This will contribute to the fulfillment of the requirements (RT2 to RT7) specified for the to-be model.

- The LBC internal supply chain process will first start with accessing the SC IS to utilize the data required by the LBC to establish its strategic sourcing plan. Because the LBC will have access to well-managed supply chain data, it will guide them when preparing their sourcing and marketing strategies. In contrast to the as-is model, the LBC, besides the SC IS, will also have its own management information system to manage the internal operations of the LBC. With the proposed model, instead of the PC recording transactions in a paper-based general ledger, the transaction will now be recorded electronically via the proposed system using any portable device (Figure 4). This will ensure the proper management of data for easy retrieving and storing. The interactions and transactions between the internal stakeholders of the LBC will be done electronically through one common established data management system. This internal open access system will enhance the timely sharing of resources, particularly information, and will help the process participants to collaborate effectively. This idea of having a well-established data and information system seems promising because it will help the LBC to have an overview of the purchases in each of the districts as well as the trends of their purchases. Again, it will contribute to the reduction of data errors and enhance the data flows needed for information sharing. Such proposals will give LBC stakeholders mobile access to information (RT1), better data management (RT3), supply chain visibility (RT5), full utilization of IT systems (RT6), and better planning (RT1) and sourcing (RT4). It will also help the LBC to improve its relationship building, which will significantly improve the selection of suppliers, as reported by [36]. The additional detailed information on the LBC to-be scenario can be found in the LBC lane (Figure 4).

- Similar to the as-is process model, the to-be complete process will also end with the interaction between COCOBOD and the customer. COCOBOD, which will be the manager of the proposed IT system, will also start its process by using data from the SC IS to establish its sourcing plans. With the to-be situation, COCOBOD will be able to record its purchases and share purchase data with its stakeholders electronically to help coordinate their collaboration activities. The to-be situation will facilitate easy consumer feedback to the complete supply chain via COCOBOD. This will help stakeholders, particularly farmers, to have an idea of where the end product of their produce is consumed (RT1). The redesigned model will provide full visibility for COCOBOD (RT5) as well as full IT utilization (RT7), better collaboration with vendors (RT7), good data management and information sharing (RT3, RT4), and strategic sourcing (RT4).

- Supply chain management components: The management component for the proposed situation will be the same as the as-is scenario but with additional functionality. COCOBOD will still be the main organization leading the planning, controlling, and monitoring functions in the overall cocoa supply chain. The proposed model extends the responsibilities of COCOBOD with IT system implementation and management. The production policy will still be Make-To-Stock (MTS). With the new model, this will be better planned and aligned with all stakeholders so process participants can have the same ultimate goal.

- Supply chain resources: In terms of resources in the form of IT systems, COCOBOD and the LBC will have their internal management systems, but there will be a global system that stakeholders such as farmers can have access to as well. This proposed system (SC IS) will help the stakeholders interact and coordinate their supply chain process. In the to-be model, the cocoa farmer will be able to have a basic application interface to interact and source the required information. The current internal IT system of the LBC will be enhanced to give access to their operation employees (PC, DM, PM, and OM). The different IT systems of the stakeholders can be enhanced to have systems-of-systems communication with the systems of other stakeholders.

6. Discussion

In this article, we have developed a framework to support the analysis and design of the business processes in the Ghana cocoa supply chain for supporting inclusiveness. Several interesting findings, with both theoretical and practical implications, have emerged from the study.

The first contribution of the research is the designed framework proposed in the study. The outcome of the analysis of the existing supply chain frameworks reveals that current frameworks provide a general approach for supply chain management; there are insufficient guidelines for deriving, designing, and analyzing the inclusiveness of supply chain business processes such as our cocoa industry case. These results affirm the study of [37,38], who also observed that existing reference frameworks in the agri-domain are not sufficient for deriving business processes. Our findings are also in line with the study of [39], who observed that the majority of current supply and value chain literature is centered on challenges and approaches for inclusiveness, linking innovation and the value chain and the examination of methods for innovation, but with less focus on approaches for analyzing supply chains. Based on this outcome, our framework (Section 4) utilizes elements from the different models to design an inclusive framework to (i) support the modeling of the as-is processes in the supply chain, (ii) help to identify role-players or stakeholders in the chain, (iii) support analysis of a supply chain to enhance inclusiveness, (iv) provide insight into the best practices or redesign scenarios for addressing supply chain issues, and (v) contribute to a better understanding of the governance structure in the supply chain. The framework was designed to contain elements that can be applied and adapted easily for different cases.

Our framework added the dimension of inclusiveness to the conceptual supply chain framework of Lambert and Cooper [21]. The SCOR model was used as a basis for process modeling, and we added design criteria and best practices for improving supply chain inclusiveness. These criteria were based on the ground criteria and principles of the LINK toolkit. As such, our framework has added explicit components for modeling and redesigning inclusive supply chains.

A second contribution is related to the application of the framework to the cocoa sector. Our case study reveals that the inclusiveness of the cocoa supply chain is limited especially concerning areas such as chain-wide collaboration, effective market linkages, equitable access to services, and fair and transparent governance, as also reported by [2,4,7,10,11,20]. Poor average scores were recorded in all these areas except for fair and transparent governance (Table 5). The study found that the stakeholders in the supply chain tend to focus on their interests and needs. There is a weak collaboration among the process participants. Coordination among the business processes of the participants and the stakeholders themselves is lacking. Because of the weak coordination link among the process participants, there is an inadequate flow and exchange of information, particularly market information. This makes it difficult for the supply chain stakeholders to operationalize and strategize their activities. With the principle of equitable access to services, the article identifies that services in the cocoa supply chain are not shared equally. Information access, for instance, is skewed; this is in line with the report of [4,7,10]. The cocoa farmers, in particular, are excluded from access to market information. Despite their key role in the sector, they have no idea about cocoa market prices. This concern weakens their stand in identifying market opportunities, and this corroborates the study of UNDP [40], which also argued that excluding weaker stakeholders affects supply chain inclusiveness. Again, COCOBOD subsidiaries will perform some quality checks on the cocoa beans from the farmers in the supply chain, but the quality checks information is not shared with the farmers. This also makes it difficult for the farmers to adhere to quality standards because they have no access to the quality standards information. We attribute the concerns of inadequate access to information and coordination among the stakeholders to the lack of well-established IT systems in the sector. The inadequate and underutilization of IT systems in the cocoa supply chain also makes it difficult for the stakeholders to share market information. Many of the respondents believe that the lack of IT systems is the chief cause of all the information-flow-related issues hindering the cocoa industry of Ghana. This is because they believe that information can only flow when there is a system for sharing the information and that this will enhance interaction among the actors, which, in turn, will enhance supply chain flows. This tends to decrease cooperation and transparency in the supply chain.

The third contribution of our work is that we propose a to-be supply process model of the Ghana cocoa supply chain with IT needs (Figure 4). The relevance of this contribution is supported by other studies on the important role and benefits associated with IT systems in supply chain information sharing [41,42,43]. The to-be model provides opportunities for improving the cocoa supply chain for supporting inclusiveness. It especially includes integrated supply chain planning and provides better supply chain visibility to the stakeholders. Implementing this model will give all the key stakeholders mobile access to information and better information and data management. Moreover, it will provide an avenue for vendor collaboration. This will help the stakeholders in the cocoa supply chain, especially cocoa farmers, to be able to do better planning and benchmarking for their businesses. In addition, the to-be model, which aligns cocoa supply chain business with IT when implemented, will enhance efficiency and effectiveness, which will, in turn, improve productivity.

The article contributes to both agri-food and IT literature. As stated earlier in the introduction, few studies in the literature have specifically focused on analyzing the current states of agri-food supply chains and designing improved business models for supporting inclusiveness. This article fills this void. This article is the first of its kind to apply elements of existing frameworks to design an inclusive supply chain framework and apply it to analyze and design future scenarios for practical cash crop (cocoa industry) cases. This innovative element of the article implies that lessons can be learned and the proposed framework and the approach can be applied to other countries and smallholder cash crops such as coffee, tea, and cotton. Concerning practical relevance, this present article has deepened the understanding of the business processes in the cocoa supply chain. It has also highlighted the inclusiveness issues in the sector, which can be used as a basis for deriving improvement and innovative strategies. The business process models provided can guide the implementation of IT systems in the sector.

The present research has focused on the key stakeholders in the domestic supply chain sector in Ghana. Future research is needed to include additional stakeholders such as customers, particularly international customers, input suppliers, and other subsidiaries of COCOBOD. Furthermore, it would be valuable to elaborate the supply chain inclusiveness score into a detailed analysis per actor. Such in-depth scoring criteria, with quantitative variables, would allow analyzing the inclusiveness among the stakeholders in the sector. Finally, this present article has focused on analyzing and designing the supply chain process to enhance inclusiveness, with less focus on a full redesign of both the process models and the to-be IT systems. The article limits the redesign to only complete supply chain systems without redesigning the internal processes of the different stakeholders. A full redesign, with a thorough evaluation, can be done to completely redevelop the business processes and IT systems.

7. Conclusions

Cocoa contributes substantially to the global commodity market and has a huge social and economic impact on Ghana’s economy. However, in the Ghana cocoa supply chain, there is a limited flow of information and unequal access to services among the stakeholders. Studies conducted on information sharing and inclusiveness in the cocoa supply chain are limited. In the supply chain literature, inclusiveness is widely studied; however, there is limited knowledge on analyzing the inclusiveness of supply chains and designing future scenarios (to-be).

Our results indicate that current supply chain frameworks are not sufficient in guiding the analysis and design of inclusive business processes for agri-food supply chains. This is because the majority of the supply and value chain studies have focused on analyzing the interdependencies and enhancing collaboration among chain partners. These studies do not focus on providing a model or performing analysis of the current states of agri-food supply chains and designing improved business models for supporting inclusiveness. The framework designed in this article provides guidelines to model as-is supply chains, analyze current supply chains for inclusiveness, and help to build future supply chain scenarios. These can help a smooth translation from as-is to to-be supply chains, especially concerning inclusiveness.

The case study reveals that the supply chain inclusiveness of the Ghana cocoa sector is limited. There is a lack of proper chain-wide collaboration, effective market linkages, and equitable access to services. The cocoa farmers, upstream of the supply chain, for instance, provide production and marketing data to downstream stakeholders. However, the farmers do not receive basic information for their production and marketing planning, although they are the main source of production-related data in the supply chain. The study also shows that the lack of access to information is not only limited to farmers; the national industry regulator (COCOBOD) is also excluded from the information-sharing network. This suggests that the stakeholders in the Ghana cocoa supply chain will be able to do much better supply chain planning if they all communicate and collaborate to enhance inclusiveness.

The study has shown that deploying IT systems to support the underlying processes will allow for the timely sharing of information and the improvement of planning and control systems accordingly. Implementing IT systems in the cocoa supply chain will have a great impact on supply chain inclusion by connecting all the stakeholders to interact efficiently. The study has revealed that implementing IT systems requires an adequate understanding and redesign of the current business processes. The to-be business process model we provided will enhance common understanding between the business and IT stakeholders and can serve as a good artifact for IT implementation for the stakeholders, especially COCOBOD and the LBCs.

This framework presented in this article focuses on business process models and does not yet include more technical architecture. Further research is needed to extend it with data, software, and infrastructure models that are needed for developing agri-food software. Furthermore, the framework can serve as a basis for a detailed quantitative analysis of the inclusiveness of the internal supply chain of the stakeholders. Future research should explore in detail the redesign and full evaluation of the internal processes of all the stakeholders in the cocoa supply chain. This will provide detailed insights to the stakeholders of prospective future scenarios in their processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A., A.K., B.T. and C.V.; methodology, E.A., A.K., B.T., and C.V.; data curation, E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, E.A., A.K. and B.T.; visualization, E.A. and A.K.; supervision, B.T. and C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Wageningen University and Research Information Technology Group, The Netherlands, supported this research financially.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented for the study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors cordially acknowledge and thank the stakeholders in the Ghana cocoa supply chain, especially COCOBOD and its subsidiaries, for their immense support for the interviews during the data collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire.

Table A1.

Questionnaire.

| Question ID | Question | Response/Possible Answers |

|---|---|---|

| Q1. | Stakeholder/cocoa supply chain actor | |

| Q2. | What is the name of your organization? | |

| Q3. | What is your name? | |

| Q4. | What is your role in the organization? | |

| Q5. | What are your current supply chain activities (financial, material, information) based on your mentioned role? | |

| Q6. | Do you use any tool (ICT gadgets) such as desktop computers, tablets, mobile phones, or paper-based systems to perform any of the above-stated activities? For mobile phones, indicate the brand and the type of internet (Wi-Fi/ Mobile data)? | 1 = Yes 2 = No |

| Q7. | If No, why? (follow-up of Q6) | |

| Q8. | If Yes, indicate the name of the specific activity, the tool, with whom do you use this tool, the information you ask, and what you receive (follow up of Q6) | |

| Q9. | Have you witnessed any change in activities in the past 5 years compared to your current activities mentioned in Q5? | 1 = Yes 2 = No |

| Q10. | If Yes, indicate these newly added activities | |

| Q11. | What tool(s) (ICT gadgets) such as desktop computers, tablets, mobile phones, or paper-based systems were you using in the past 5 years to perform your old activities? | |

| Q12. | Indicate for each tool the activity and the cocoa supply chain partner you interact with using the mentioned tool | |

| Q13. | How many departments does your organization have? | |

| Q14. | Which department (s) manages your supply chain? |

|

| Q15. | Does your organization have a business website? |

|

| Q16. | Who built this website? |

|

| Q17. | Who maintains this website? | |

| Q18. | What are the uses or functions of this website? Indicate for each function the beneficiaries (function of the website to whom), the kind of information provided by the website, and the source of the information (information on the website was obtained from who) | |

| Q19. | What information systems (IS)/software are currently in use by your organization? For each IS/software, indicate the uses, year installed or built, who built it/them, who maintains it/them, and what ‘problem’ obstructs their uses | |

| Q20. | How do the existing IS/software stated in Q19 relate to each other? | |

| Q21. | What supply chain management issues do you think are affecting the Ghana cocoa industry? 1. Difficult to interact with members in the chain 2. Lack of information systems for information sharing among members 3. Delay in delivery time in the flows (material, financial, and information flows) 4. Lack of trust among other supply chain members 5. Other, specify _________________________ |

Appendix B. SCOR Best Practices Example

Table A2.

BP.183 Integrated Business Planning. Adapted from [33].

Table A2.

BP.183 Integrated Business Planning. Adapted from [33].

| Definition: Integrated business planning (IBP) is a business process and capability that seeks to improve organization performance by creating an enterprise-wide operating plan. The goal of the IBP process is to develop consensus on a single business plan that aligns with supply chain strategy, tactics, and execution plans. | |

| sP1 | Plan Supply Chain |

| sP1.1 | Identify, Prioritize, and Aggregate Supply Chain Requirements |

| sP1.2 | Identify, Prioritize, and Aggregate Supply Chain Resources |

| sP1.3 | Balance Supply Chain Requirements with Supply Chain Resources |

| sP1.4 | Establish and Communicate Supply Chains |

| People | |

| HS.0016 | Capacity Planning/Management |

| HS.0029 | Customer Relationship Management (CRM) |

| HS.0046 | ERP Systems |

| HS.0048 | Forecasting |

| HS.0058 | Inventory Management |

| HS.0067 | Linear programming |

| HS.0070 | Logistics network modeling |

| HS.0074 | Master Scheduling |

| HS.0079 | MRP Systems |

| HS.0102 | Production Planning Capacity Utilization |

| HS.0103 | Production Scheduling |

| HS.0132 | Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) |

Appendix C. Process Models of Cocoa Supply Chain Stakeholders

Appendix C.1. Existing Supply Chain Systems of the Cocoa Farmer

Figure A1.

Process model of the cocoa farmer.

Figure A1.

Process model of the cocoa farmer.

- Supply chain network structure: The cocoa farmers interviewed for the research were sole owners of their cocoa farming business. Despite this, some cocoa farmers belong to farmers’ co-operatives and other farmers’ unions or associations, which categorized them with a different organizational structure from the other farmers. The survey results reveal that the cocoa farmers, in addition to their role, also interact with the purchasing agents of the buying companies and the Seed Production Unit (SPU) of COCOBOD.

- Business processes: The business process of a cocoa farmer has been found to contain several activities, and we grouped these into four core processes: production planning, sourcing of inputs, and producing and delivering dried cocoa beans to the LBCs. We modeled these core activities using one pool separated into two different lanes. The pool is labeled cocoa farmer, and the lanes are named production planning and source seedlings and produce and deliver dried cocoa beans (aaPENDIXed and Execution plans. the overall planning in the supply chain.\olders). From the survey study, it is revealed that cocoa farmers have some connections with the COCOBOD SPU and PC but are not included in most of the overall activities in the supply chain. The production planning activities of the cocoa farmer are triggered by the cocoa production season, and this is represented (start of production season) using the start event notation of the BPMN (Figure A1, Appendix C). The receipt of the inputs from the SPU leads to subsequent activities such as planting cocoa seedlings (see Figure A1, Appendix C for more details). The activities of the cocoa farmer end after delivering (bag and deliver cocoa beans; see Figure A1, Appendix C) and selling the dried cocoa beans to the LBC PC and receiving a cash payment.

- Supply chain management components: Within the cocoa farmer internal supply chain, the cocoa farmer formally coordinates and oversees the planning, but sometimes, COCOBOD will perform some monitoring activities.

- Supply chain resources: As stated earlier, the main system used by the cocoa farmer is the farmer passbook, used for keeping production and sales records. Moreover, some of the farmers interviewed used their own tablets and mobile phones, but these are used solely for making phone calls.

Appendix C.2. Existing Supply Chain Systems of the LBCs

- Supply chain network structure: The research identified four main process participants in the LBC business process. The process participants are the purchasing clerk (PC), district manager (DM), port manager (PM), and operation manager (OM). These main process participants work collaboratively to oversee the internal process of the LBCs in the cocoa supply chain. The PCs act as agents in the villages on behalf of their LBCs. The DMs live in the district capitals of the cocoa-producing districts. They work with the PCs to organize dried cocoa purchases and the transportation of cocoa from the local communities to the in-land ports. The PMs operate at the in-land ports and are responsible for receiving bagged cocoa beans from the district manager.

- Business processes: The collaboration diagram of the LBCs is modeled in one pool containing four different lanes (Figure A2, Appendix C). There is an interaction with other external participants (farmer, COCOBOD account, and WPO). These external participants are also represented with a black box pool. The activities in the LBC business process are triggered by the cocoa harvesting season, and this is represented with a BPMN start event, start of harvest season, as shown in the PC lane. The business process at the LBC is initiated when the PC requests funds from the DM to purchase dried cocoa beans (Figure A2, Appendix C). After receiving the requested funds in the form of cash from the DM, the PC uses the money to purchase cocoa dried beans from farmers.

- The internal business process of the LBC ends when the PM hands over the bagged cocoa beans to the COCOBOD CMC and manually sends copies of the paper-form cocoa take-over documents to the OM (Figure A2, Appendix C). From the field interviews, the majority of the respondents revealed that the process at the COCOBOD port takes a lot of time (long waiting time), and this is attributed to the human involvement and the intensive paper-based system at the in-land ports.

- Supply chain management components: The LBCs oversee the coordinating, planning, controlling, and monitoring functions in their internal supply chain systems. Moreover, COCOBOD performs some monitoring functions on the activities carried out by the LBCs in the Ghana cocoa industry.

- Supply chain resources: The LBCs interviewed were asked to indicate the underlying IT systems used to support their business processes. The results revealed that the LBCs use management information systems with subsystems such as accounting, port management, field operations management, human resources, and inventory control. We found that these systems are used by the LBCs in their headquarters. Paper-based systems also form part of the systems widely used by the LBCs.

Appendix C.3. Existing Supply Chain Systems of COCOBOD

Figure A2.

The collaboration process model of the LBC.

Figure A2.

The collaboration process model of the LBC.

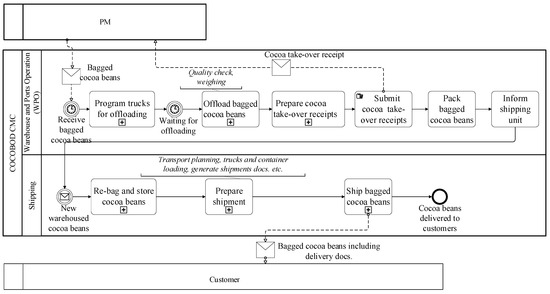

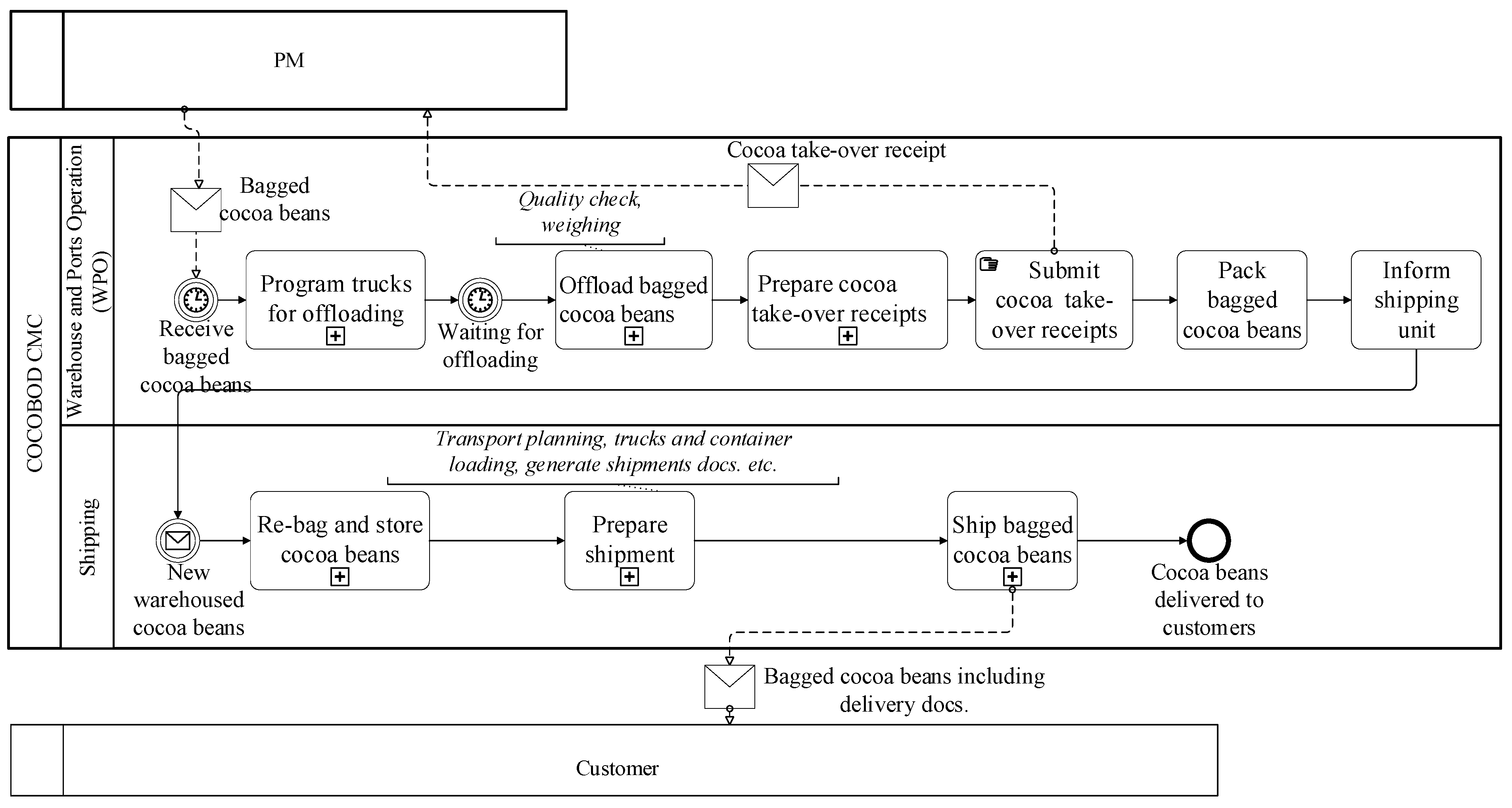

- Supply chain network structure: Unlike the business processes of the cocoa farmer and the LBC, the article discovered two main organizational units, WPO and shipping, as the main process participants in the COCOBOD CMC process. The LBC and customer are the key interacting partners of the CMC. The article reveals other supporting organizational units such as accounts, auditing, human resources, and IT within the CMC. For the scope of the study, the present article does not zoom in on the business processes performed by these participants.

- Business processes: The main business process performed by the CMC has been modeled as one pool diagram containing two lanes (Figure A3, Appendix C). The customer process has been visualized using a black pool box. The business process starts when officials of the WPO take over dried bagged cocoa beans from the LBC PM (Figure A3, Appendix C). Preparation of records by the WPO for taking over the cocoa beans follow, and this has been indicated as prepare cocoa take-over receipts on the CMC process model. The data gathered from the records are used to prepare the cocoa take-over paper receipts, which are given to the LBC PM as a contractual document for taking over the cocoa beans. The business processes of the CMC, which finalize the domestic supply chain in the Ghana cocoa industry, come to an end when the relevant shipping documents are prepared (generate shipping documents) and the cocoa beans, including delivery documentation, are delivered to the customer.

Figure A3.

The collaboration process model of the COCOBOD CMC.

Figure A3.

The collaboration process model of the COCOBOD CMC.

References

- Gayi, S.K.; Tsowou, K. Cocoa industry: Integrating small farmers into the global value chain Cocoa industry: Integrating small farmers into the global value chain. U. N. Conf. Trade Dev. 2016, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monastyrnaya, E.; Joerin, J.; Dawoe, E.; Six, J. Assessing the Resilience of the Cocoa Value Chain in Ghana. 2016. Available online: www.resilientfoodsystems.ethz.ch (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Glin, L.C.; Oosterveer, P.; Mol, A.P.J. Governing the Organic Cocoa Network from Ghana: Towards Hybrid Governance Arrangements? J. Agrar. Chang. 2014, 15, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarmine, W.; Haagsma, R.; Sakyi-Dawson, O.; Asante, F.; van Huis, A.; Obeng-Ofori, D. Incentives for cocoa bean production in Ghana: Does quality matter? NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2012, 60–63, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredua, N.; Ambrose, K. Economic Cost-Benefit Analysis of Certified Sustainable Cocoa Production in Ghana. 2010. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/97085/ (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Anthonio, D.C.; Aikins, E.D. Reforming Ghana’s Cocoa Sector—An Evaluation of Private Participation in Marketing. 2009. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1021865&dswid=-1653 (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Laven, A. The Risks of Inclusion. 2010. Available online: http://www.bibalex.org/search4dev/files/356068/188051.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Gockowski, J.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Sarpong, D.B.; Osei-Asare, Y.B.; Dziwornu, A.K. Increasing income of ghanaian cocoa farmers: Is introduction of fine flavour cocoa a viable alternative, Q.J. Int. Agric. 2011, 50, 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Nuertey, D. Sustainable Supply Chain Management for Cocoa in Ghana; Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology: Kumasi, Ghana, 2015; Available online: http://ir.knust.edu.gh/bitstream/123456789/7505/1/DorcasNuertey.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Roldan, M.B.; Fromm, I.; Aidoo, R.; Roldan, M.B.; Fromm, I.; Aidoo, R. From Producers to Export Markets: The Case of the Cocoa Value Chain in Ghana. J. Afr. Dev. 2013, 15, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi, C.O.; Aboagye, M.O.; Antwi, J.O.; Ampadu, S. Information Efficiency and the Cocoa Supply Chain in Ghana. Am. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 123–138. Available online: http://www.aijssnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_6_December_2015/16.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).