Abstract

Increased tourist pressures can cause the deterioration of nature-based tourist destinations and adversely affect visitor satisfaction. This study aims to identify how public participation using mobile devices on-site can assist in assessing future design scenarios for a popular nature-based destination, within a short day trip from Christchurch in Aotearoa New Zealand. An online survey using participants’ mobile devices at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks identified domestic tourists’ motivational, satisfaction and dissatisfaction factors, as associated with age and visit frequency at the destination. These factors were linked to site experiences, particularly being out in nature, that could be used to design future scenarios for similar nature-based settings in Aotearoa New Zealand. Four future scenarios using 2D photomontages were used to rank domestic visitor preferences for changing paths and tracks, fencing, signage, structures and people. The study found that the low-impact scenario with the least people was the most desirable. This high level of sensitivity of New Zealanders to change in outdoor recreational destinations suggests that nature-based settings must be designed and managed with considerable care to minimize the perception of over-crowding and the deterioration of the site experience, particularly for return visitors.

1. Introduction

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, tourism was New Zealand’s largest export industry, with approximately USD 17.5 billion annual expenditure from international visitors and USD 24.4 billion from domestic travelers [1]. It is an export service industry relying on both information content and physical geography. Prior to 2020, New Zealand residents and government agencies, such as local councils, the NZ Department of Conservation and the NZ Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, became increasingly concerned about the environmental pressure that high numbers of international tourists were placing on iconic natural landscapes. “Freedom campers” (those visitors camping on public land not recognized as a camping ground or holiday park) were particularly considered to be at fault of willful damage, even though they comprised only 3.4% of international tourists [2]. Since the coronavirus pandemic, New Zealand’s borders have generally remained closed to incoming and outgoing international travel, prompting 62% of New Zealanders to use their travel funds on domestic travel within a twelve-month period [3]. Data from 2019 showed that 90% of domestic leisure travel was by car, with 61% of this travel being day trips [3]. Natural settings in NZ have seen increasing pressure on local infrastructure as movement around the country has increased during the post-pandemic recovery period [4,5]. Thus, understanding the motivations and satisfaction, or push-pull factors, of domestic tourists at a destination within an easy drive from a major New Zealand city remains of significant interest.

Management action is needed before destinations deteriorate beyond repair [6]. The transfer of theoretical knowledge of sustainable tourism to the public and private sector remains minimal [7]. Work on sustainable tourism development has not progressed much beyond the formulation and discussion of principles and assumptions [8]. Ali and Frew [9] (p. 3) suggested that sustainable tourism could become an effective concept for tourism planning and development through the use and application of technology. In general, there has been a low level of implementation of technology for sustainable tourism for a range of reasons, including fear of its use, lack of awareness of how it can be used, and a lack of resources and expertise available to tackle more advanced uses beyond websites and internet marketing [9]. At the heart of sustainable tourism development lies the process of decision-making, which is focused on the best allocation of resources, within a limited period of time, that satisfies all stakeholders involved, including managers and visitors [9] (p. 61). Destination managers need to filter considerable amounts of information and develop possible scenarios to decide on workable solutions that address multiple environmental challenges. Tourism technologies could be of some assistance in preventing the deterioration of iconic natural landscapes in Aotearoa New Zealand. This study questions how domestic New Zealand visitors’ motivations and satisfaction, captured on-site using mobile devices, could inform landscape design decisions for a nature-based tourist destination and assist with concept revision if/when changes become necessary on the site.

1.1. Sustainable Tourism Technologies

Tourism technologies are likely to allow local communities to become dynamically networked, which co-produces value for everybody interconnected within the ecosystem [10]. Age segments of domestic tourists in New Zealand have increasing levels of technological literacy. Virtual communities are becoming a significant force in the tourism sector. Rheingold [11] (p. 58) defined a virtual community as “a group of people who may or may not meet one another face-to-face and who exchange words and ideas through the mediation of computer bulletin boards and networks”. They depend on a high level of trust between community members, which suggests relying on realistic and authentic information content for decision-making in the planning and development of favorite tourist sites.

Computer simulation is a technological tool that can be used to model how a system operates over time, describe existing patterns of visitor use, monitor indicators of tourist pressure, investigate the effectiveness of changes to site conditions, and check hypothetical situations for optimum decision-making before the cost of implementation on-site is invested. It can be used to facilitate practical design research with the public through realistic images about proposed changes, and foster more informed decision-making by state agencies [12]. Scholars have noted the movement from “e-tourism”, to “smart-tourism”, to developments in augmented reality (AR) [13]. Technology now allows tourists to be both physically and virtually present in some locations, such as with augmented reality (AR) or virtual reality (VR) [9] (p. 103). There has been a low level of implementation of these tools in nature-based settings in New Zealand due to a lack of awareness of how they can be used, a lack of resources, and a lack of specialist expertise available for advanced uses of the technologies available.

Mobile phones and tablets, however, have become the primary means of accessing the internet, and are a critical component of tourists’ expectations and satisfaction [14]. These devices allow the personalization of services for a diverse range of tourists. Location-based services (LBS) can increase tourist satisfaction and contribute to sustainable tourism development at destinations. There is an increasing richness of multimedia content for self-representation using photos, videos and 3D virtual experiences available at tourist destinations [15], influencing the tourist decision-making process on where to go, what to do and how to get there.

1.2. Tourist Motivations

For clarification, in this study, “domestic tourists” are considered to be any visitors to the destination who are multicultural residents of the country, i.e., simply have a residential postcode in Aotearoa New Zealand. These visitors were expected to live in the vicinity of the protected natural area in question, or to be citizens of this country who were visiting the area for the first time or frequently, and consequently felt a sense of national interest and ownership of it.

The division of domestic tourists into eight market segments, according to the Ministry of Tourism [16], gives an overview of the complexity of tourist motivations for travel in New Zealand. These segments include:

- (a)

- empty nesters aged 55 and over who are often female and principally driven to travel by seeing people they love in safe, familiar and affordable settings;

- (b)

- single people without children aged under 40 who are technologically literate and looking for exciting, different, entertaining, challenging yet familiar experiences;

- (c)

- couples without children or whose children have left home, aged 25 and over, looking to be with their partners, away from the pressure, challenges and responsibility of everyday life;

- (d)

- single people or couples without children under 40, looking for an escape from the stress and pressure of everyday life with family and friends in destinations that are not familiar and that provide a complexity of experiences;

- (e)

- solo parents aged 25 to 54, often female, looking for a break that is affordable, peaceful, relaxing, safe and familiar, and a destination that is family-friendly, welcoming, easy and not challenging;

- (f)

- couples with children aged 25 to 54 looking to spend time with family, sharing involvement in a wide range of active interests and outdoor experiences;

- (g)

- single people or couples that have children and extended family members living at home, under 40 who enjoy short breaks and longer holidays in NZ often prompted by visits to family and friends or by education;

- (h)

- single people who live at home with parents, siblings or friends, aged under 40, looking for exciting, different, entertaining and challenging activities and destinations.

Green Travel News [17] reported that baby boomers, generation Xers and millennials tend to look for environmental experiences that are authentic as they search for meaning in their holiday breaks. Questions continue to be asked as to whether tourists are likely to be positively motivated towards choosing sustainable routes, behaviors and experiences at their chosen destinations, given adequate information on these sites and additional information on transport, accommodation, seasonality and attractions [18]. Information overload is a risk at this early stage of the travel experience, and trust in information sources is paramount. While in transit, tourists now use QR codes for boarding passes, e-tickets and interacting with posters. They can also be used as a convenient direction or way-finding tool. At the destination, a convergence of technologies using global positioning systems (GPS), geographic information systems (GIS) and location-based services (LBS) through smart devices offer a vast array of capabilities, from tourist guides to mobile audiovisual (AV) commentaries relevant in real time. This allows customization and flexibility on any route, dispensing with the clutter that must be carried around, linking to other post-visit experiences and a better-quality experience for each tourist. Tourists can be alerted when they are close to an attraction, and gain further information, including sustainable tourism information and expected behavior specific to a location. Augmented reality connects physical geography to information content [9] (p. 118). Post-trip reflections on the positives and negatives of the trip experience are a valuable part of improving visitor experience at sustainable tourism destinations.

1.3. Tourist Satisfaction

Tourist satisfaction is critical as to whether a tourist returns to a destination or not and encourages others to visit or not. Satisfaction is the relationship between expectations and perceived experiences or outcomes [19]. Important factors influencing tourist satisfaction include: safety, security, quality of sites and attractions, accommodation, water quality, cleanliness and hospitality at a destination, and access to accurate and reliable information [20]. In one New Zealand study, pull motivational factors were better predictors of overall satisfaction than motivational push factors, with a high level of repeat visitation at a forest park in a mountainous landscape near Hamilton in the North Island [21]. In this study, push-pull factors related to a nature-based destination are studied in various scenarios to develop an understanding of overall visitor satisfaction and repeated visitation.

The interpretation of a destination has been found to a be an educational process aimed at revealing the meanings and relationships within a place [22]. Interpretation creates an image of a specific destination and community that can be disseminated among visitors and can contribute to community education, pride and sense of place. It plays an important role in improving visitor experience, knowledge and understanding, which aids in the protection and conservation of places and cultures. It can be achieved through diverse methods, including physical signage, multimedia displays, tour guides, maps, workshops, and personal experience. Interpretation is also a key driver of landscape design in high-quality tourist destinations.

1.4. Landscape Design for Destination Resilience

Very little attention has been paid to the power of landscape design in managing change at tourism destinations. Most research involving the design of the tourist experience is in architectural tourism or tourism focused on architectural interests [23], rural village tourism focused on idyllic rural life [24], and tourist resorts focused on resort quality and surroundings [25]. Few studies have focused on design practices for nature-based tourism to mitigate adverse changes to landscape attractions. The landscape design of nature-based settings uses both ecological design and experiential design approaches to strengthen both the identity (how something is perceived and understood) and relevance (the degree to which something is related or useful to what is happening or being talked about) of a tourist destination [26,27].

Klein-Hewett [27] pointed out that many tourism studies have concentrated on the carrying capacity of destinations and the inevitable decline of amenities, management and service provision as tourist destinations change over time. However, these studies rarely consider the landscape or its designed amenities in redirecting the life cycle trajectory of tourist destinations to accommodate changing types of tourists and their interests [27] (p. 4). Klein-Hewett [27] proposed an approach that involves destination concept (its aesthetic, identity, etc.) creation, concept maintenance and concept revision. Concept revision occurs if/when there is a shift and an acceptance of a loss of some kind followed by the reconsideration of the destination’s concept to adapt to a new reality. Domestic visitors’ motivations and satisfaction could inform landscape design decisions for a nature-based tourist destination and assist with concept revision if/when changes are needed on site.

This study aims to identify how public participation using mobile devices on-site could assist in assessing future design scenarios for a popular nature-based destination, within a short day-trip from Christchurch in Aotearoa New Zealand. It looks at the push-pull factors motivating domestic tourists, which could be used to better plan, design and implement sustainable nature-based tourism development at the destination level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context of Study

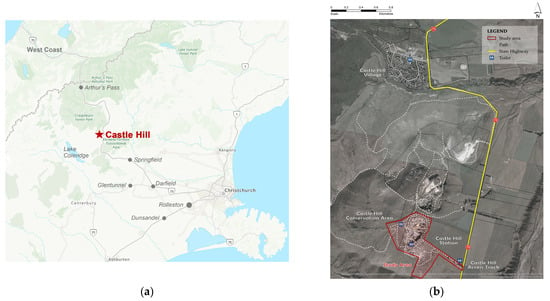

The Kura Tāwhiti/Castle Hill Reserves are located in the Upper Waimakariri Basin of the Canterbury region of the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand. The study site is situated approximately 100 km west of Christchurch (approx. 1.5 h drive) on State Highway 73, otherwise known as the West Coast Road connecting Christchurch with the West Coast (goldfields in 1866) via Arthur’s Pass. This makes the study site one of the most highly accessible tourist sites for those from Christchurch. It sits within the Castle Hill Basin in the Southern Alps, bounded to the west by Craigieburn Range (with summits up to 2100 m), to the southeast by the Torlesse Range (1950 m), to the northeast by Flock Hill (998 m) and to the east by Broken Hill (1500 m) [28] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Location of Castle Hill between Christchurch and Arthur’s Pass. (b) Location of study site at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks on the West Coast Road or Highway 73.

The study site, known as Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks, features spectacular formations of limestone rocks, in association with the cave and sinkholes around Cave Stream, the limestone strata of Pebble and Gorge Hills, and the rocks of Broken River. This makes the study site very popular with a range of age groups of differing levels of fitness and interests. It is generally considered to be alpine or inter-montaine, with warm summers and cool winters. Winds are predominately from the northeast, with colder southerly winds that can be strong, gusty and damaging. Soils consisting of early Tertiary sediments are friable, porous, low in clay and sandy in texture [28] (p. 7). The lower slopes of the basin would have once supported a mountain beech (Fuscospora cliffortioides) forest, with mountain totara (Podocarpus totara) and smaller patches of mixed hardwood forest. Following human occupation in around 1300 AD, the forests were progressively burned and largely replaced by grasslands. Currently, the study site is covered with modified short tussock and open grassland, but is also the home of rare indigenous plant species such as the Castle Hill buttercup (Ranunculus crithmifolius sub-species paucifolius), the Castle Hill forget-me-not (Myosotis colensoi) and Brockie’s harebell (Wahlenbergia brockiei) [28] (p. 49).

The study site has special significance to Māori tribes from the Waitaha to the Ngāi Tahu iwi [29]. In 1998, the area was given the designation of tōpuni tikanga (traditional custom of chiefly persons having mana and protecting others by placing their cloak over them) in the Ngāi Tahu Deed of Settlement with the Crown. This designation recognizes the cultural, spiritual and historical values of Kura Tāwhiti, which means “treasure from a distant land” [29]. Kura Tāwhiti was one of the mountains claimed by the Ngāi Tahu ancestor Tane Tiki, son of celebrated chief Tuahuriri. The nearby mountains were famed for kākāpō, and Tane Tiki wanted their soft skins and glowing green feathers for a cloak to be worn by his daughter Hine Mihi. Stories such as this link Ngāi Tahu to the landscape of Te Wai Pounamu, and the traditional knowledge of trails, rock shelters and places for gathering kai (food). The rock outcrops and their rock art have tapu (forbidden or sacred) status for Ngāi Tahu. This means that climbing onto the tops of the rocks is considered to be desecrating Ngāi Tahu ancestors and their sacred status. The limestone rocks were thought to resemble battlements by European travelers and the area was named Castle Hill [29]. This makes the study site an important bicultural landscape within the South Island.

The study site is frequently visited by both international and domestic tourists on a self-drive trip, being independent travelers or organized tours, on their way to Arthur’s Pass. Arthur’s Pass National Park received 155,000 visits in 2019, of which an estimated 38% came from day trippers, and this is expected to increase [29]. This makes the study site highly appropriate for studying the impacts of this type of expanding tourist market in Aotearoa New Zealand. It is free for all visitors to access, with no ticketing system. Based on tourist blogs, it appeals to tourists with a love of nature, a preference for spectacular scenery, and a potential interest in bouldering (a type of rock climbing without ropes or harnesses) or the relaxation of an exploratory short (20 min) or long (2 h) walk. For many visitors, it is a short stop on State Highway 73 on the way to or from Arthur’s Pass, but for some, it is a destination in itself.

2.2. Development of Visualization Scenarios

Future scenarios were developed using photomontages based on the NZ Department of Conservation [30] Track Construction and Maintenance Guidelines, and aimed to visualize a positive visitor experience with increasing levels of modification that were in keeping with the unique characteristics of the natural environment at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks. The starting point was the existing level of modification in November 2019 and a “do nothing” scenario. Scenarios two, three and four were constructed using Adobe Photoshop and depict incremental increases in visitors of 50% for each scenario, i.e., from 6 to 12, to 25, to 50 people along the entrance pathway to the rocks. Associated changes to the path, fencing, signage and structures aligned with these increasing numbers of people are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Four photomontages to simulate future scenarios for entrance to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks on State Highway 73 (Images by Yuqing He and Marcus Robinson, 2019).

In scenario one, “very low visitation”, the path to the rocks is 1.5 to 2 m in width, starting at the gravel car park with a capacity of approximately 50 to 100 vehicles, including an overflow car park on grass accessed through a gate. This was considered the “do nothing” scenario. The fencing along the entrance path to the rocks is comprised of a wire and post stock fence, as grazing paddocks belonging to Castle Hill Station are located along the north side of the path. Signage is minimal, with a timber covered noticeboard located near the toilet block at the eastern entrance and one sign on the path titled “Sculpture” in stone-art. These two structures, the noticeboard and toilet block, are the only shelter available from weather conditions on the site. Three white toilet cubicles are also located closer to the rocks but out of shot. A shelterbelt of pines had recently been removed from the entrance, as well as two large individual pine trees along the path, due to the rewilding of Pinus sp. This is an invasive plant species in New Zealand and was becoming a significant issue in the vicinity. Three to four tracks are visible through the rocks and, in June 2021, the planting of patches of mixed natives was undertaken by the NZ Department of Conservation.

In scenario two, “low visitation”, a digital image representing approximately ten to fifteen visitors having the capacity to walk along the path in twos and threes is shown. The path was widened to approximately 2 to 2.5 m, assumed to be the result of increasing foot traffic and the lack of fencing protection on the south side of the path. Five visible tracks into the rocks were added, assumed to be caused by increasing foot access with more visitors. The fencing condition remained the same as in scenario one. A standard Department of Conservation (DoC) sign was added to the image to provide information on walk duration and distance. One covered structure, a toilet or a shelter, was illustrated at the foot of the rocks, recognizing the need to adapt to increased visitor numbers.

In scenario three, “moderate visitation”, a digital image was constructed illustrating approximately fifteen to twenty-five visitors walking along the path. The path was again hypothetically widened to two to three meters, and seven visible tracks were added to scenario one. Timber edging was introduced on the south side of the path to define its limits and subtly discourage from visitors from trampling the grass, preventing further widening of the path. Other static interpretive signage replaced the DoC signage to provide visitors with more detailed information of the site, including Māori significance and environmental information related to the site history, and stories. One more covered structure was included near the rocks to provide shelter and further information for visitors.

In scenario 4, “intense visitation”, an image was constructed with twenty-five to fifty visitors walking along the path. The path was straightened and widened to four meters due to increased foot traffic. A total of ten visible tracks into the rocks was added to scenario one. Stock fencing was installed on the south side of the path to reduce impacts on adjacent areas. Digital, multilingual signage replaced the static interpretive signage, equipped with a touch screen for visitors to interact with selected information according to their interests. Three covered structures at the base of the rocks were added to ensure visitors had protection from adverse weather conditions.

2.3. Data Collection on Site

Field survey work was undertaken on-site during a high visitation period, over four consecutive weekends from 16 November 2019 to 8 December 2019, from 8.30 a.m. to 4 p.m. each day, except during adverse weather conditions when visitor numbers were very low. Survey data were collected using participants’ own mobile devices or a standby device if participants had a problem with their own devices. A web-based Qualtrics XM survey application was accessible on-site. Some paper-based surveys were also provided for those wishing to participate without mobile devices, and were completed manually to facilitate diversity.

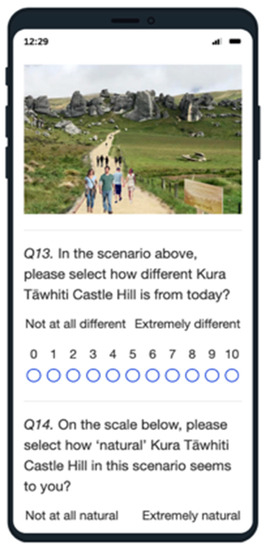

The digital Qualtrics XM platform offered significant time savings for both data capturing and data analysis, but it did limit the detail visible to participants (Figure 2). It did, however, create added interest for younger participants, even when researchers were not on site. With a QR code on explanatory posters, some participants joined the study without being approached. However, the majority of participants were approached at the entrance to the footpath to the rocks, near the carpark, and asked if they lived in New Zealand. If so, they were encouraged to undertake the online survey after they had visited the rocks, with one out of two researchers assisting with any questions or technical difficulties. Participants had to be over 18, and the purpose of the study, processes for ensuring confidentiality and anonymity, and information on how to access the self-administered survey, were given verbally as well as at the start of the survey. University signage, shelters and chairs were available for participants on-site, although some chose to complete the survey at a later time.

Figure 2.

Qualtrics survey on a mobile device.

2.4. Survey Design

The survey comprised 30 questions (Appendix A), taking approximately 15 min for participants to complete. There were four main sections of questions about (a) the visitor and their trip to Kura Tāwhiti, (b) their satisfaction and dissatisfaction with their visit, (c) participant responses to possible future scenarios for the site and (d) participant demographics.

The first section asked for responses regarding the participants’ place of residence in Aoteraoa New Zealand, their residential postcode, the year of their birth, their number of visits to Kura Tāwhiti, when they had most recently visited the site before the visit, the reason for this visit, and other places they also considered visiting. In the second section, we were interested in what participants liked the most and the least about the site, as well as how they ranked their level of satisfaction with five factors (tracks and wayfinding, signage and information, toilets and carparking, indigenous planting and ecology, and visitor numbers).

In the third section, four visual scenarios were depicted in photomontages of possible future site conditions that altered multiple factors incrementally. As a manipulation check, participants were asked to evaluate and rank on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 10 (extremely) each scenario based on (a) how “different” the 2D photomontage looked to the current conditions on site, (b) how “natural” the 2D photomontage seemed and (c) how likely would it be that they would return if the scenario was to eventuate. They were also asked how concerned they felt about the future of the site on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely concerned), and to provide text-based comments as to the reasons for this. Finally, the survey concluded with demographic questions regarding gender, ethnicity and educational achievement.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data collected from Qualtrics XM were converted into an SPSS dataset. SPSS v.25 was used to calculate descriptive statistics and frequencies, and perform statistical analyses. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were employed to determine significant variations of variables across sub-groups of participants. Additionally, paired sample t-tests were used to establish differences between variable scores collected within the same survey instrument.

It was important to relate participants’ ratings of their reasons for visiting the site to their age groups and the number of times they had visited Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks prior to the day of the survey. From a design perspective, understanding factors contributing to the level of satisfaction of the visitors with their experience of the site was also important when assessing the visualized scenarios. Textual responses to the open-ended question—“What did you like MOST about Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill?”—were thematically coded and visitors’ satisfaction factors were identified.

3. Results

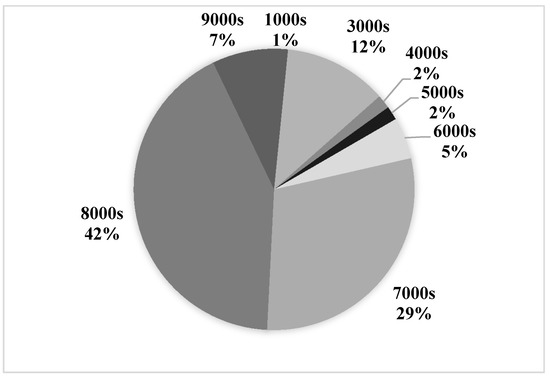

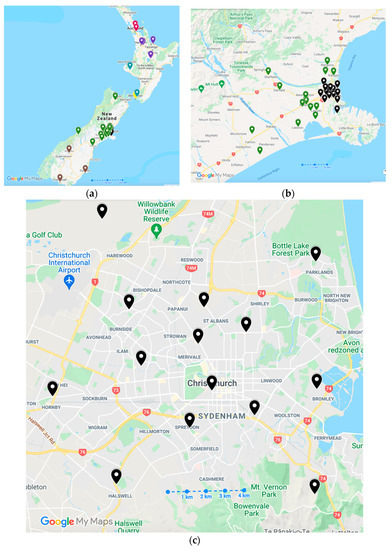

3.1. Visitor and Trip Characteristics

A total of 134 surveys were collected from participants, comprising 55% (n = 74) females and 43% (n = 57) males, with 2 that did not identify with either and 1 that preferred not to say. The average reported age of the visitors was 42, with 16% (n = 18) generation Z (born 1995–2001), 33% (n = 38) millennials (born 1980–1994), 34% (n = 39) generation X (born 1965–1979), and 17% (n = 20) baby boomers (born 1944–1964) or older. The highest education level attained comprised 2% (n = 3) unidentified, 4% (n = 5) with school certificates, 8% (n = 11) with high school certificates, 9% (n = 12) with technical certificates, 8% (n = 11) with diplomas, 32% (n = 43) with degrees, 10% (n = 14) with postgrad diploma, 16% (n = 22) with masters degrees, and 10% (13) with PhDs. The ethnic background of the sample consisted of 73% (n = 98) NZ European, 1% (n = 2) Māori, 1% (n = 2) Chinese, and 24% (n = 32) identified as other. It was the first time visiting Kura Tāwhiti for 36% (n = 48) of the participants, 16% (n = 22) had visited once before, 18% (n = 24) had visited between two and four times before, and 30% (n = 41) had been at least five times before. Domestic visitors in this study came from areas across New Zealand, including from Christchurch (42%), Canterbury, Marlborough and West Coast Districts (29%), Otago and Southland (7%), Waikato (12%), Wellington (5%), Lower Hutt/Taranaki Districts (4%) and Auckland (1%) (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Proportion of participants (n = 126) with residential postcodes within New Zealand. (9000s = Otago and Southland Districts; 8000s = Christchurch City; 7000s = Canterbury, Marlborough and West Coast Districts, 6000s = Wellington, 4000s and 5000s Lower Hutt/Taranaki Districts; 3000s = Waikato Districts; 1000s = Auckland).

Figure 4.

Departure locations (based on postcodes) across (a) New Zealand, (b) Canterbury Region and (c) Christchurch areas for domestic New Zealand visitors to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks. (Points in brown = 9000s Otago and Southland Districts; black = 8000s Christchurch City; green = 7000s Canterbury, Marlborough and West Coast Districts, yellow = 6000s Wellington, blue/green = 4000s and 5000s Lower Hutt/Taranaki Districts; purple = 3000s Waikato Districts; red = 1000s and 0900s Auckland).

3.2. Visitor Motivations

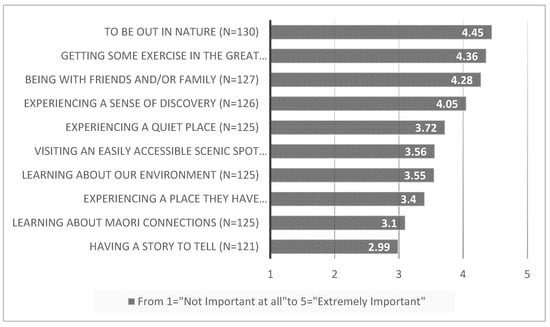

The relative importance “scores” were placed by participants on their motivations for visiting Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks and are shown in Figure 5. The strongest motivations were to be out in nature, getting exercise outdoors, sharing the experience with friends and family and a sense of discovery. The weakest motivations for the whole group were learning about Māori connections and having a story to tell.

Figure 5.

Motivations of participants for this visit to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks (score figures indicate mean for each motivational factor). Score differences of 0.20 are significant (p < 0.05 in paired samples t-tests).

Paired samples t-tests were performed to determine whether score differences were significant, and any difference of 0.20 or greater was significant (p < 0.05). When examining adjacent scores (ranked one higher or lower), three out of nine scores were significantly different; when compared with adjacent +/−1 (two higher or lower), five out of eight were significantly different, and adjacent +/−2 (three higher or lower), seven out of seven were significantly different.

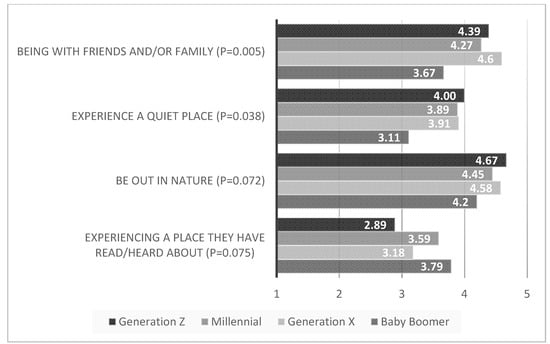

Some of the motivations changed over sub-groups of participants, namely, age groups and visit frequency. The four most dynamic motivations across age groups (one-way ANOVAs) were being with friends and family and experiencing a quiet place, which were significantly different across groups at p < 0.05, as well as being out in nature and experiencing a place they had read/heard about, being significant at p < 0.10 (Figure 6). Interestingly, being with friends and family was more important for the generation X group, and less important for the baby boomer group, although the opposite was found for experiencing a place they had read/heard about. These results suggest that at least some of the motivations may be influenced by age.

Figure 6.

Top four most dynamic motivations across age groups for a visit to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks (figures indicate mean for each group).

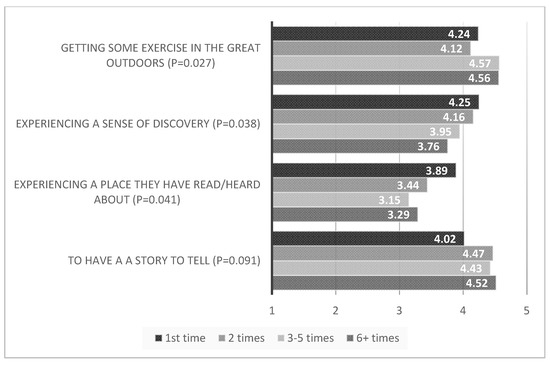

When examining the motivations across visit frequency, there were also significant differences (one-way ANOVAs) across the groups, with outdoor exercise, a sense of discovery, and experiencing a place they had read/heard about being significantly different across groups at p < 0.05, and to have a story to tell being significantly different at p < 0.10 (Figure 7). In general terms, discovery and experiencing a place they had heard/read about was more important in earlier visits, and outdoor exercise and a story to tell gained importance in later visits. Additionally, only one motivation, experiencing a place they had read/heard about, was in the top four across both age and visit frequency groups, offering support for having two sub-groupings.

Figure 7.

Top four most dynamic motivations across visit frequency groups for a visit to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks (figures indicate mean for each group).

3.3. Visitor Satisfaction Factors

The respondents’ satisfaction factors in relation to their visit to the site are shown in Table 2. A total of 128 responses were provided to this question, among which 1 response was deleted due to its irrelevance to the question. Among the remaining 127 responses, 24.4% of respondents noted scenery as the factor with which they were most satisfied. The rocks were the second most common factor for 22.8% of participants, followed by climbing and bouldering, with 17.3% and 6.3%, respectively.

Table 2.

Visitors’ satisfaction factors in Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks (n = 127).

Responses to the question “What did you like LEAST about Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill?” allowed the visitors’ dissatisfaction factors to be identified (Table 3). A total of 122 responses were provided for this question. Among those responses, two were deleted due to irrelevance to the question. Of the remaining 120 responses, nearly one-third of the respondents (29.2%) thought that the current site did not have any factors that made their experience unsatisfactory. The most commonly mentioned factor with which respondents were dissatisfied was too many people. A number of the respondents (17.5%) noted that there were currently too many visitors, which adversely affected their experience. In addition, the busy car park and lack of signs were also factors which respondents mentioned, as noted by 5.8% of participants for both factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Visitors’ dissatisfaction factors in Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks (n = 122).

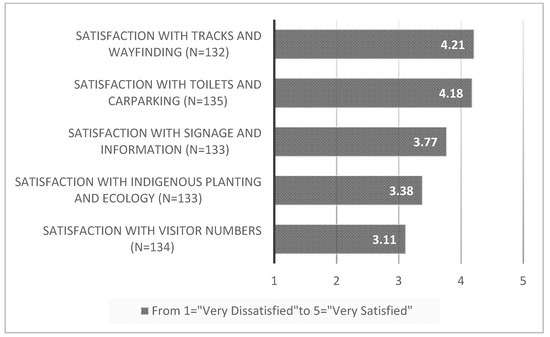

Overall satisfaction was reported, with differences across the visitor satisfaction scores tested using paired sample t-tests. Figure 8 shows that visitors were most satisfied with tracks and wayfinding, as well as toilets and carparking (no significant difference between them), followed by signage and information (p < 0.01), then indigenous planting and ecology (p < 0.01), and the lowest satisfaction was with visitor numbers (p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Satisfaction with the visit to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks (figures indicate mean for each factor).

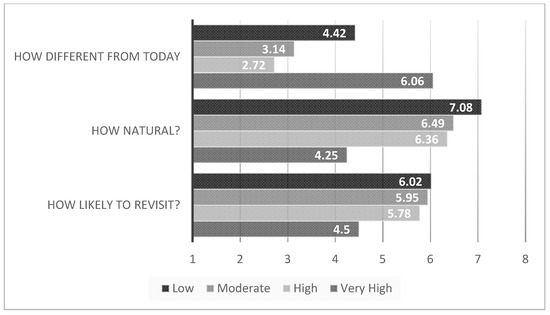

3.4. Interpretations of Scenarios

Visitors reordered a series of photomontages with four levels of hypothetical scenarios (low, medium, high and very high impact) based on path construction, fencing, signage, structures, and potential encounters with people in terms of (a) how different was the represented site from the existing site, (b) how natural was the represented site and (c) how likely would you be to revisit the represented site? While the low-impact scenario was closest to the existing path and fencing at the time, visitors reported the high-impact scenario to be closest to what they had experienced that day. Figure 9 shows that visitors reported the low-impact scenario to be the most natural and as resulting in the highest likelihood of them revisiting Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill. These results clearly show that visitors preferred lower-impact scenarios to higher-impact scenarios.

Figure 9.

Ordering of four future scenarios (low, moderate, high and very high impact) from 1 (the “most” preferred) to 4 (the “least” preferred) for three questions related to satisfaction at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks (figures indicate mean rating of each scenario for each question).

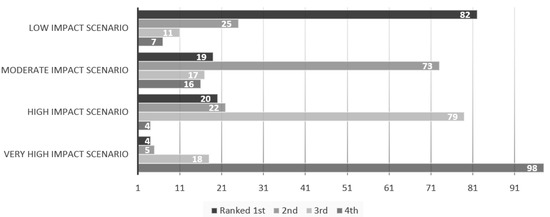

3.5. Acceptability of Scenarios

The level of acceptability of each of the four scenarios, ranked on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 being the most acceptable and 4 being the least acceptable, is shown in Figure 10. The 129 responses were firstly grouped into positive acceptability, where participants ranked the scenarios as 1 or 2, meaning that respondents were willing to accept a scenario as a potential future scenario for Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill. When responses ranked a scenario as 3 or 4, these were then grouped into the negative acceptability group, meaning that respondents were not willing to accept these as future scenarios. These results clearly show that visitors preferred lower-impact scenarios to the higher-impact scenarios.

Figure 10.

Ranking of four future scenarios (low, moderate, high and very high impact) on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 being the most acceptable and 4 being the least acceptable, for Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks (figures indicate total count for each ranking).

Respondents’ acceptability of scenario one and scenario two were the most positive, with 85.3% and 71.3% of respondents being satisfied with these two scenarios, respectively. However, scenarios three and scenario four were not favored by the respondents, with only 35.7% and 7.8% of respondents having a positive view regarding these two scenarios, respectively.

When asked about the reasons for ranking these scenarios in this way, the majority of participants (75.7%) believed that the number of visitors was the most important factor that concerned them. Among these, about one-third (33.9%) of the respondents thought that too many visitors would adversely affect their site experience and destroy the site’s current natural and peaceful atmosphere. The site has special significance for some groups of people (e.g., Ngāi Tahu), and many regard the site as a spiritual place. Increasing visitor numbers led to concerns regarding a lack of respect for the sacredness of the site. In addition, 28.6% of the respondents were concerned that too many visitors would damage the natural environment. Excessive human activities may have an impact on the growth of endemic flora and fauna, and further aggravate the current degradation and erosion problems along tracks on the site. Some respondents (16.1%) also mentioned that too many visitors might cause problems in the future management of the site. For instance, the existing infrastructure, such as footpaths, toilets and parking spaces, may not be able to cope with an excessive number of visitors.

In addition to the number of visitors, participants also responded to factors such as signage, fencing and path changes. Some respondents (9.5%) hoped that there would be more signage on the site, explaining the site’s geological history, cultural significance and stories related to Ngāi Tahu perspectives. This was followed by 8.1% of the respondents who expressed their concern about setting up fences. They were worried that this would prevent them from freely accessing certain areas in the future, thus reducing the chance of exploring some of the rocks. Few participants expressed a view regarding the form of fencing and signage. Only one respondent mentioned that multiple signs would add more enjoyment to the site, and another noted that s/he did not want a highly modified environment. A small number of respondents (4.1%) felt that the current path should not be widened.

4. Discussion

A common way of conceptualizing the interaction between tourist motivations and the site experience uses Dann’s push-pull framework [31]. Push factors are those factors that drive a desire to travel. Pull factors are those destination attributes that attract tourists to visit a site. This study identified a number of push factors that created a desire for visitors to visit Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks. Most were there because they primarily wanted to be out in nature. This motivation was combined with other key socio-psychological motivations, such as getting some exercise in the great outdoors, sharing the experience with friends and family, and experiencing a sense of discovery. Some motivations seemed to be influenced by age group and others by visit frequency, suggesting that motivations can change with either age or number of visits. This variation opens up the possibility of designing specific pull factors of a nature-based setting in such a way as to maintain what is much loved about a place, such as Kura Tāwhiti, by differently aged, first-time and return-visit segments of the domestic tourist market. Other studies have identified destination changes such as glacial retreat [32,33] and coral bleaching [34] as changing the push-pull dynamic. Borsje and Tak [26] have promoted a landscape-based design strategy for the Dubrovnik Riviera in Croatia. However, as far as we are aware, this study is the first to propose nature-based design scenarios as a means of changing the push-pull dynamics of New Zealand destinations.

Getting some exercise in the great outdoors was the second most important motivation, or push factor, after being out in nature, but was not significantly influenced by age group. This suggested that this destination appealed to all age groups, including those looking for exciting, physically challenging yet familiar outdoor experiences, those with a wide range of active outdoor interests, such as horse riding, walking, hiking and bouldering, as well as those looking for an affordable, easily accessible, not physically challenging yet peaceful, relaxing, and safe place to visit. Outdoor exercise and having a story to tell had greater importance for those visitors who returned to this destination multiple times. This was likely aligned with the top three pull factors being the scenery, the rocks, and climbing. Seeing many more people, fencing off some areas and/or controlling tracks up through the rocks for conservation purposes would likely degrade the return visitor experience at Kura Tāwhiti.

Being with friends and family was the third most important motivation, a push factor particularly for the generation X group (aged 40–55) compared to other age groups. The destination seemed to appeal to New Zealand residents who wanted to see people they loved in a safe, familiar and affordable setting; those wanting to spend time with their partners, away from the pressure, challenges and responsibilities of everyday life; those looking for a destination that was family-friendly to share involvement with children in outdoor activities; and those wanting to enjoy a short day trip from Christchurch or a longer holiday to the West Coast with family and friends. This type of motivation likely aligned with dissatisfaction factors, such as seeing too many people, busy car park, bad weather, rubbish, graffiti, muddy conditions, no running water, toilets and bad language. These aspects would have a negative impact on the family or group experience. Designing the site to primarily reduce visitor encounters would be challenging, but would facilitate “on our own” private group experiences.

Experiencing a sense of discovery or a place they had read/heard about motivated older age groups, particularly baby boomers aged 57–77 with children and extended family members living at home, adding to their level of education. Over three quarters of visitors had university qualifications, suggesting that improved interpretive signage would improve the visitor experience, particularly for those visiting Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks for the first or second time. This was confirmed with a lack of signage being one of the top three dissatisfaction factors at this destination.

This study clearly shows that domestic visitors in New Zealand are particularly sensitive to changes in the natural environment being visited, and they prefer future scenarios depicting the low impact of change on the site. Groulx et al. [32] also found that environmental change would have a significant impact on the pull of Athabasca Glacier in Canada. Motorized transport adaptations (helicopters and snow-coaches) were considered unacceptable, as they would adversely affect the natural character of the destination. However, because the photomontages included multiple manipulations across five aspects of impact (path width, additional fencing, signage types, added structures and numbers of people) together, it was unclear what the importance of each aspect would be on the attitudes and revisiting intentions of these visitors. In landscape design, multiple factors are frequently changed all at once in multifunctional spaces. Design scenarios generally integrate many factors at the same time, depending on the numbers of people visiting a place. For instance, more people could mean increased future funding for better signage, path maintenance and number of toilet facilities. A conjoint analysis involving paired comparisons of individually manipulated aspects could shed further light on the contribution of particular design elements to overall visitor satisfaction.

Domestic visitors in New Zealand are extremely sensitive to increasing visitor numbers in protected areas. Nature-based tourism studies, particularly in New Zealand and Norway, have identified a “culture clash” between domestic and international tourism [35]. These authors point out that for domestic tourists, place attachment and national ownership are central to how New Zealand residents see particular nature-based settings as part of their everyday lives. The post-COVID “Do Something New, New Zealand” campaign in 2020 [36] was directly aimed at such a sentiment of national unity and ownership, where domestic tourists were strongly encouraged to experience their own country and support local businesses in New Zealand destinations. During the post-pandemic recovery period, it is likely that visitors remain keen to be out in nature and not see other people so they can stay safe. Interestingly, New Zealanders have not been seen as “tourists” when they visit nature-based settings because they are exploring their own country. Overseas visitors are considered to be “tourists” who cause unwanted impacts on protected public land, rather than outdoor recreationalists as a whole [35].

With over 78% of participants from Christchurch and the South Island, there was a high sensitivity to visitor numbers and seeing too many people at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks, the highest of all the dissatisfaction factors in this study. This is in complete agreement with the findings of Doorne [37], wherein visitors from north Asia (Korea and Japan) registered a higher tolerance of crowding compared to New Zealand and Australian visitors to Waitomo Caves in New Zealand. However, at the Summer Palace in Beijing, 53% of local Beijing residents and 51% of domestic Chinese tourists thought that the area was too crowded or overcrowded [38]. The high-impact scenario at Kura Tāwhiti, with the greatest number of people depicted on the path to the rocks, was ranked as the least “natural”, the least acceptable and the least likely to encourage a return visit to the site out of all four design scenarios. This suggests that redesigning the Kura Tāwhiti site to reduce perceived overcrowding would have a highly beneficial impact on domestic visitor experiences if tourist numbers rise. We suggest that nature-based design would be a preferable alternative to introducing ticketing or passes to popular sites, such as Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks. Modifying the long straight path to the rocks, using endemic planting design and curved lines, and allowing the dispersal of tracks over a wide area, would reduce the visibility and encounters with other visitors in the far and intermediate distance. This is supported by Groulx et al. [32], who found that changing the trail, fence and bridge was acceptable to Canadian and non-Canadian visitors at the Athabasca site. They did, however, point out that any adaptations must carefully maintain the visitors’ desire for being out in nature, and so managers must prioritize the ecological integrity of the destination.

In line with maintaining the ecological experience of visitors to a place like Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks was the unknown desire of visitors to use technology, such as mobile devices, in these settings. The Kura Tāwhiti site has good network coverage for mobile devices, and this is not always the case in nature-based settings in the mountains in New Zealand. Based on the experience of recruiting participants for this study at the car park, those visitors who wanted to escape the use of technology by being out in nature declined our request to be involved in the study, and therefore were not represented in our findings. However, our response rate was relatively high in relation to those who were approached (approximately 60–70%), and many were enthusiastic about adding to their experience of Kura Tāwhiti by using mobile devices to help university staff propose future design scenarios for the site.

Those who were aged under 40, with or without children, technologically literate and looking for exciting, different, entertaining, challenging yet familiar experiences, or those wanting to share involvement with family in a wide range of active interests and outdoor experiences, seemed keen to use mobile devices for geo-caching (a type of global treasure hunt using a global positioning system (GPS) to find or hide stashes of objects), or for taking and posting photos or videos online with a story to tell. These segments of the domestic market are likely to be interested in location-based services (LBS) that can increase their visit satisfaction and contribute to sustainable tourism at the same time. Physical signage could be kept to a minimum on-site and supplemented with up-to-date augmented reality (AR) information on mobile devices, which would allow the personalization of information services and photographic opportunities. This would align with the increasing public contribution of multimedia content, such as photos, videos and 3D virtual experiences, being posted for this and other nature-based destinations. As Cassinger and Thelander [39] (p. 171) have explained, the Instagram gaze represents a way of seeing and experiencing a destination as ordinary and everyday by those who are highly experienced social media users. For those looking for a story to tell, illustrating the destination using spontaneous, authentic and trustworthy photographs is intended to generate audience responses through the number of likes, comments and followers. Here, the focus changes from a relationship with a memorable object to a relationship of social identity. Abbott [40] also promoted using mobile devices for visitors to engage in replanting forests in publicly protected areas. Domestic visitors with mobile devices will greatly influence the tourist decision-making process on where to go and what to do in the future.

Klein-Hewett [27] proposed a design approach that involved (a) concept creation, (b) concept maintenance and (c) concept revision. Concept creation is a phase in which there is the formation and eventual manifestation of a destination’s concept (its aesthetic, purpose and identity). In the concept maintenance phase, tourism managers attempt to prolong and reinforce the destination and its concept as a relevant option for the preferred clientele. Concept revision is the phase in which there is a reckoning with and acceptance of a loss of relevance, and the reconsideration of the concept to adapt to a new reality with a reevaluation of the preferred clientele. This study aimed to progress the efforts of designing and planning research to elevate the importance of design in tourism scholarship [27]. We suggest that well-designed tourist destinations can avoid controlling tourist access using ticketing or passes to popular sites such as Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks. Visualizations using 2D photomontages are very common, but also very limiting in terms of the representation of an authentic site experience for design purposes. Dynamic 3D interactive visualization scenarios in the future will be more able to adequately deliver questions/actions for public participation in planning, designing and implementing sustainable experiences at nature-based sites in protected areas, in order to better cope with change. Visualizing and managing change at the destination level is challenging but has the potential to foster improved motivational pull factors, in line with key push factors, while maintaining familiar and unfamiliar visitor experiences of being out in nature.

5. Conclusions

Destination managers need to take action based on practical information that addresses multiple environmental challenges before destinations deteriorate beyond repair [6]. This study questioned how domestic New Zealand visitors’ motivations and satisfaction, captured on-site using mobile devices, could inform landscape design decisions for a nature-based tourist destination, and assist with concept revision if/when changes become necessary on the site. Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks was selected as the study site, as it is a popular day trip destination for domestic tourists traveling between Christchurch and Arthur’s Pass. The study used an online survey with 134 volunteer participants approached at the carpark, who were residents of a location with a New Zealand postcode. Four future design scenarios were developed using photomontages based on the NZ Department of Conservation Track Construction and Maintenance Guidelines [30]. These 2D images aimed to depict a positive visitor experience with increasing levels of modification that were in keeping with the unique characteristics of the natural environment at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks.

The most common motivational push factor for domestic tourists at this site was wanting to be out in nature. This motivation, however, was combined with other motivations, such as getting some exercise in the great outdoors, sharing the experience with friends and family, and experiencing a sense of discovery. These were found to be influenced by either age group or visit frequency, or both. The top three pull factors were the scenery, the rocks, and climbing at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks. Outdoor exercise and having a story to tell held greater importance for those visitors who had returned to this destination multiple times. Being with friends and family seemed to align with dissatisfaction factors, such as seeing too many people, busy car park, bad weather, rubbish, graffiti, muddy conditions, no running water, toilets and bad language, having a negative impact on the family or group experience. Experiencing a sense of discovery or a place they had read/heard about motivated older age groups, particularly baby boomers aged 57–77, with a lack of signage being one of the top three dissatisfaction factors at this destination.

This study confirmed that domestic visitors in Aotearoa New Zealand are extremely sensitive to increasing visitor numbers in protected areas, as other studies have found [35,37]. With over 78% of participants from Christchurch and the South Island, there was a high sensitivity to visitor numbers and seeing too many people at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks, the highest of all the dissatisfaction factors in this study. The high impact scenario at Kura Tāwhiti, with the greatest number of people depicted on the path to the rocks, was ranked as the least “natural”, the least acceptable, and the least likely to encourage a return visit to the site out of all four design scenarios. This suggests that redesigning the Kura Tāwhiti site to reduce perceived overcrowding would have a highly beneficial impact on domestic visitor experiences if tourist numbers rise. Many domestic visitors, though not all, seemed keen to use mobile devices in a nature-based setting, adding to the visitor experience as well as decision-making on how to better manage the site to retain what is much loved about Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill Rocks in the future. Further work on dynamic 3D interactive visualizations of future scenarios is needed to assist in delivering public preferences for planning, designing and implementing sustainable experiences at nature-based sites in protected areas of Aotearoa New Zealand, in order to better cope with change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.; methodology, G.L. and Y.H.; software, G.L. and D.D.; investigation, G.L. and Y.H.; resources, G.L. and Y.H.; data curation, G.L. and D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L., D.D., Y.H. and X.H.; writing—review and editing, G.L. and D.D.; visualization, Y.H.; referencing, G.L. and X.H.; project administration, G.L.; funding acquisition, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Lincoln University Centre of Excellence, “kick start” seed grant #INT1126 found at https://research.lincoln.ac.nz/our-research/case-studies/visualising-a-new-tourism-landscape-through-the-eyes-of-domestic-visitors-in-nature-based-settings-of-the-selwyn-district-new-zealand (accessed on 10 November 2021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Lincoln University (Approval #2019-62 on 7 October 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data will be publicly available after further work is undertaken with the NZ Department of Conservation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Marcus Robinson for his graphic support, as well as Emma Stewart and Stephen Espiner for their methodological guidance and support of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Qualtrics Survey Questions

- Q1.

- Where do you currently live? Aotearoa New Zealand or Overseas

- Q2.

- What is your NZ postcode?

- Q3.

- Are you over 18 years old?

- Q4.

- When were you born? Year

- Q5.

- Is this your first visit to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill?

- Q6.

- How many times have you been here?

- Q7.

- When was your most recent visit (approximately) before today?

- Q8.

- Why did you want to come here today and how important was this to you?

- Q9.

- What other places did you consider visiting before coming to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill?

- Q10.

- What did you like MOST about Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill today?

- Q11.

- What did you like LEAST about Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill today?

- Q12.

- On the scale below with 1 being very dissatisfied and 5 being very satisfied, please select your degree of satisfaction with each of the following at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill?

- Q13.

- In the scenario #1 above, please select how different Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill is from today?

- Q14.

- On the scale below, please select how ‘natural’ Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill in this scenario #1 seems to you?

- Q15.

- On the scale below, if this scenario #1 was to eventuate, how likely would it be for you to return to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill in the future?

- Q16.

- In the scenario #2 above, please select how different Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill is from today?

- Q17.

- On the scale below, please select how ‘natural’ Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill in this scenario #2 seems to you?

- Q18.

- On the scale below, if this scenario #2 was to eventuate, how likely would it be for you to return to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill in the future?

- Q19.

- In the scenario #3 above, please select how different Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill is from today?

- Q20.

- On the scale below, please select how ‘natural’ Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill in this scenario #3 seems to you?

- Q21.

- On the scale below, if this scenario #3 was to eventuate, how likely would it be for you to return to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill in the future?

- Q22.

- In the scenario #4 above, please select how different Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill is from today?

- Q23.

- On the scale below, please select how ‘natural’ Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill in this scenario #4 seems to you?

- Q24.

- On the scale below, if this scenario #4 was to eventuate, how likely would it be for you to return to Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill in the future?

- Q25.

- On the scale below (1 being the MOST and 4 being the LEAST) please move each image up and down to rank how ‘acceptable’ each of these scenarios seem to you at Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill?

- Q26.

- On the scale below, how do you feel overall about the future of Kura Tāwhiti Castle Hill?

- Q27.

- Please explain your answer to the question above.

- Q28.

- Are you? Female or Male or Other or Prefer Not to Say

- Q29.

- Which ethnic group do you belong to?

- Q30.

- What is your highest level of educational qualification?

References

- Tourism Industry Aotearoa. Quick Facts and Figures. Available online: https://www.tia.org.nz/about-the-industry/quick-facts-and-figures/ (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). International Visitor Survey—Freedom Camping by International Visitors. Available online: https://www.mbie.govt.nz/immigration-and-tourism/tourism-research-and-data/tourism-data-releases/international-visitor-survey-ivs/international-visitor-survey-analysis-and-research/freedom-camping-by-international-visitors-in-new-zealand/ (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Tourism New Zealand. Domestic Travel View Report—Quarterly July 2021. Available online: https://insights.tourismnewzealand.com/assets/Tourism-New-Zealand/Consumer-research/Domestic-research/Domestic-Travel-View-Report-July-2021.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Campbell, M.; Marek, L.; Wiki, J.; Hobbs, M.; Sabel, C.E.; McCarthy, J.; Kingham, S. National movement patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic in New Zealand: The unexplored role of neighbourhood deprivation. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 903–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Fusté-Forné, F. Post-Pandemic Recovery: A Case of Domestic Tourism in Akaroa (South Island, New Zealand). World 2021, 2, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Mathieson, A. Tourism: Change, Impacts and Opportunities; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhanen, L. Progressing the Sustainability Debate: A Knowledge Management Approach to Sustainable Tourism Planning. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable Tourism Development: A Critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, A.; Frew, A. Information and Communication Technologies for Sustainable Tourism; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheingold, H. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier; Addison-Wesley: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, S.R. Computer Simulation as a Tool for Planning and Management of Visitor Use in Protected Natural Areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 600–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, S.; Pennings, M. Online and on tour: The smartphone effect in transmedia contexts. In The Routledge Companion to Media and Tourism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 414–423. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, M.; Shin, H.H. Tourists’ Experiences with Smart Tourism Technology at Smart Destinations and Their Behavior Intentions. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1464–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Tourism, technology and ICT: A critical review of affordances and concessions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Tourism. Domestic Tourism Market Segmentation—Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.tourism.net.nz/images/domestic-tourism-downloads/ExecutiveSummaryStage2.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Green Travel News. The Future of Travel: Green Value. Available online: http://greentravelerguides.com/green-travel-trend/ (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Tyrväinen, L.; Uusitalo, M.; Silvennoinen, H.; Hasu, E. Towards sustainable growth in nature-based tourism destinations: Clients’ views of land use options in Finnish Lapland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 122, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.-H.; Foster, D. Using HOLSAT to evaluate tourist satisfaction at destinations: The case of Australian holidaymakers in Vietnam. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; O’Connor, P. Information communication technology—Revolutionizing tourism. In Tourism Management Dynamics: Trends, Management and Tools; Buhalis, D., Costa, C., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, S.; Ryan, C. Mountain Areas and Visitor Usage–Motivations and Determinants of Satisfaction: The Case of Pirongia Forest Park, New Zealand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilden, F. Interpreting Our Heritage; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, G.B.C. Tourism by Design: Signature Architecture and Tourism. Tour. Rev. Int. 2015, 19, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, T.; Giorgi, E.; Ni, M. Landscape, Architecture and Environmental Regeneration: A Research by Design Approach for Inclusive Tourism in a Rural Village in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMorran, C. A Landscape of “Undesigned Design” in Rural Japan. Landsc. J. 2014, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsje, J.; Tak, R. The regional-local nexus: A landscape-based integral design strategy for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 19, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Hewett, H. Design as an Indicator of Tourist Destination Change: The Concept Renewal Cycle at Watkins Glen State Park. Land 2021, 10, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn District Council. Castle Hill Village Reserves Management Plan 2019 Review. Available online: https://www.chca.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/MGMNT-PLAN-REVIEW-DOC-05-AGM-VERSION-27FEB2019.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Department of Conservation. Kura Tāwhiti Treasure from Afar. Available online: https://www.doc.govt.nz/about-us/our-partners/maori/kura-tawhiti/ (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Department of Conservation. Track Construction and Maintenance Guidelines. Available online: https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/about-doc/role/policies-and-plans/track-construction-maintenance-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Dann, G. Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1977, 4, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groulx, M.; Lemieux, C.J.; Lewis, J.L.; Brown, S. Understanding consumer behaviour and adaptation planning responses to climate-driven environmental change in Canada’s parks and protected areas: A climate futurescapes approach. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1016–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Lu, A.; Ning, B.; He, Y. Impacts of Yulong Mountain glacier on tourism in Lijiang. J. Mt. Sci. 2006, 3, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppel, H. Climate change and tourism in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, K.; Espiner, S.; Perkins, H.C. Cultural Clash: Interpreting Established Use and New Tourism Activities in Protected Natural Areas. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 10, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism New Zealand. Do Something New, New Zealand! Available online: https://www.tourismnewzealand.com/news/do-something-new-new-zealand/ (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Doorne, S. Caves, Cultures and Crowds: Carrying Capacity Meets Consumer Sovereignty. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G. Exploring the Shared Use of World Heritage Sites: Residents and Domestic Tourists’ Use and Perceptions of the Summer Palace in Beijing. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassinger, C.; Thelander, Å. Co-creation constrained: Exploring gazes of the destination on Instagram. In The Routledge Companion to Media and Tourism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, M.R. Practices of the wild: A rewilding of landscape architecture. LA+ Interdiscip. J. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 1, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).