Abstract

This paper aims to investigate Google’s role in European media sustainability. In order to understand the implication of this digital intermediary in the news industry, we have analysed all of the projects funded through Google’s DNI Fund from 2016 to 2020. After revising each report, we have classified the data available, including the full amount of money awarded, chronologically marking every new country added to the fund and all the media outlets involved in each project. We argue that Google’s role is truly beneficial for the medium and long-term sustainability of European media because it offers both financial support and a successful path for media companies to truly embrace its digital technology potential. However, it also has some added weight in terms of transparency (a key element in sustainability practice and standards) and press independence. Besides the existing correlations between the awarded countries and the changes that have affected media legislation in Europe, our findings show an alarming scarcity of information regarding both the continuity and the conditions of each funded project. Our proposed agenda for future research consists of an in-depth investigation of each beneficiary, which will entail several interviews as well as different case studies of all the participants in Europe.

1. Introduction

The arrival of the new century has not been easy for traditional news media companies. Digital technologies have radically affected the whole news media production chain. While digital natives were quicker and more agile in adopting and implementing innovations, some legacy media struggled to survive and to understand why and how technology was a real disruptor [1,2]. Change is always present in the digital world, which requires a positive and proactive attitude towards it instead of looking at it as merely an ordinary expense. Its impact does not stop at infrastructure: it implies profound changes to product conceptualization, working environments, profiles and routines, and relationships with the audience [3].

Besides the technological disruption, news media companies were also severely affected by the global economic crisis starting in 2007 [4]. Advertising expenditure went almost flat in some markets. When the economy started to recover, the environment was already different: social media platforms started to attract users’ time and attention, and with them the advertising expenditure of brands and companies. Since then, traditional media companies have been dealing with a redefinition of their business models [5,6], looking for new income sources and trying to reduce direct costs [7].

At the same time, new challenges have arisen which make good journalism more necessary than ever. Populism, disinformation and misinformation campaigns, and the illicit use of algorithms to influence voter attitudes have been threatening democracies around the globe [8,9]. Due to this situation, governments have been trying to help news media companies in order to minimize the impact of those menaces [10]. Private companies and institutions have tried to help news media companies to understand the opportunities for their companies’ sustainability that a true adoption of digital technologies could offer. Nonetheless, this support has led to some concerns about the independence of the media industry [11].

In this context, Google’s DNI Fund (also known as the Digital News Innovation Fund, a European initiative created by Google in April 2015) is a compelling case to analyse. In its aim to support “high-quality journalism through technology and innovation” [12], Google has evaluated more than 3000 applications from 30 European countries and offered more than EUR 300 million in funding directly oriented to media since 2016 [13]. It is worth mentioning how Google’s financial help has been able to provide European media with the much-needed resources to develop projects that involve both digital technology and media’s core mission: producing and distributing news. Despite its important presence within the media community, the DNI Fund has received little to no attention from an academic perspective. Even so, it is worth mentioning Nunes and Canavilhas’ discussion of journalism innovation through the analysis of seventeen Google Digital News Innovation Fund initiatives selected from those appearing in its three-year report [14]. Noguera-Vivo, on the other hand, focused more on projects such as the Google Newsroom [15], while Nartise, in her master thesis, investigated the journalistic challenges that the DNI Fund might be addressing [16].

Through the analysis of all the projects funded by the DNI Fund Initiative from 2016 to 2020, this paper aims to investigate Google’s role in the sustainability of today’s news media outlets. In the pages that follow, it will be argued how Google’s strategies could be truly beneficial for the sustainability of European media, while we also consider the added weight in terms of media freedom, independence and transparency.

1.1. Sustainability and Transparency

Uncertainty due to the economic crisis, along with digitalization and the emergence of new ways for audiences to be informed and entertained [17] has had a strong impact on the finances of news media companies [18]. Both the drop in advertising expenditures and the consolidation of social media platforms as a desirable destination for advertisers have created a “perfect storm” situation [19], where almost every company has dealt with the need to support heavy structures, from technical to human, that have required a new balance between incomes and expenses [20]. Now more than ever, sustainability is crucial for news media companies, particularly the traditional media brands, as new digital natives emerge with fewer structural costs and more flexible approaches to hiring [21].

In practice, sustainability tries to eliminate dysfunctional aspects in the finances of a company and in its business model [22]. One of the key aspects of sustainability in business is the aim of change in the corporate model that comes from within the company, and is not limited only to problem solving as a secondary aspect of business interests [23]. However, another term has increased its importance for the improvement of sustainability practices and standards in the past few years: transparency [24], usually defined as the ability of business “not only to know internally that they are exercising due diligence but also to show externally that it is the case” [25]. Online databases, monitoring initiatives or traceability projects have had quite an impact in society, especially in terms of accountability. Examples such as the Panama Papers investigations or the recent disclosure of the Pandora Papers report have created a new (and more transparent) media paradigm. Thus, transparency nowadays has a critical role in both sustainability and corporate responsibility strategies. Disclosing information about the names of suppliers, buying firms or purchasing practices is no longer enough: the society of information demands more clarity in transactions, policies, and the impact of a company’s activities [25].

1.2. Google’s Role in Europe

In an environment characterized by continuous flow of free information, both media and brands are desperately seeking the public’s attention. The sustainability of media businesses involves not only new strategies and policies that affect the internal structure of their activities, but also their identity as transparent and responsible media, and how journalistic outlets identify and define themselves to their audiences. In Europe, for example, news media companies have had a variable relationship with public or private funding. Tech giants’ efforts to fight for room in the local news market has had some concerning results for the industry, sometimes described as “asking for a bull that broke everything in a ceramics shop to come and piece things back together” [26].

Incidentally, the much-needed independence in covering what is going on implies a need to be very critical and transparent with where money comes from. When a government or public administration helps non-public media, it is easy to hear some criticism about how able and free that media outlet will be to act as the government’s watchdog. Public-funded advertising is in some markets an accepted way to assure some public money for media companies, although in these cases the law is usually very clear about the transparency and fairness of this investment. Instead, private funding has usually taken the form of advertising or sponsorship. Therefore, the rules tend to be more flexible than when public money is involved. The DNI Fund, for instance, has taken advantage of that flexibility since its beginning.

Google’s relationship with media companies has often been complicated [27]. The launching of Google News was contested in several countries, as media companies understood that Google was benefitting from their work creating news content to attract visitors to its own news service. Google tried to convince them that this service was another way to access their websites and therefore it would increase their visits and, potentially, their advertising income [28]. In some countries, such as Spain, media editors asked for government support and a “Google tax” was created. Consequently, Google closed its service for those markets.

Google’s tools, on the other hand, have a huge impact on society, and they are well known by regular users, and especially journalists. Several academic studies focus on these kinds of tools [29,30]. However, those apps and especially the data that the company collects from users has raised some concerns recently. In October 2020 the Justice Department of the United States filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google, accusing the company of “abusing its dominance” and “operating like an illegal monopoly” [31]. During recent events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, it has been proved that companies such as Google, Facebook or Amazon are considered as public utilities and have served a great purpose in terms of information and purchasing during the different lockdown periods. The European Union, however, is more preoccupied about what companies are doing with user data, especially when targeting online ads. According to Belgium’s privacy watchdog, online advertising in Europe likely broke “the 27-country bloc’s tough data protection standards” [32] in the past years.

In this context, the creation of the Google DNI Fund could be seen as an attempt to reconcile with the media sector, providing them with economic and technical support. Despite the company’s efforts to help and back quality journalism, some publishers have expressed their concern over the shift in distribution towards platforms. Their anxiety about the “loss of control over the destination of stories, the power of their brand and their outlets’ relationship with the viewer or reader” [33] has sometimes prevailed over the benefits of being Google’s standard-bearers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The DNI Fund

The DNI Fund, also known as the Digital News Innovation Fund, is a European initiative created by Google in April 2015 aiming to support “high-quality journalism through technology and innovation” [12]. Since 2016, the Fund has evaluated more than 3000 applications and offered more than EUR 51m in funding to European projects [34,35], that raised up to EUR 150m three years later [13]. This fund is part of the Digital News Initiative, which launched in 2015. According to Google’s last report, they have awarded different amounts to more than 662 projects in 30 countries in Europe, which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evolution of DNI funds awarded since its beginning. Source: compiled by author.

By the beginning of the project, Google was already working with some European publishers: Les Echos in France; Die Zeit and FAZ in Germany; La Stampa in Italy; NRC Media in the Netherlands; El País, Unidad Editorial, Vocento, Grupo Godó, Grupo 20 Minutos and El Confidencial in Spain; The Financial Times and The Guardian in the United Kingdom [36]. Other organisations such as the European Journalism Centre (EJC), the Global Editors Network (GEN) and the International News Media Association (INMA) were also taking part in Google’s cruise in Europe [36].

To apply for funding, each participant (or group of participants, or media group) must submit an application describing the problem they have or face, the solution that might be required, and the proposal for either a project, the development of a tool or an app, or any other form of addressing their pressing issue. The funding process has room for three types of projects: Prototype, Medium and Large [34]. Prototype projects, designed for early-stage ideas, are “open to organisations, individuals, and those organisations comprised of just one individual for projects requiring up to EUR 50k of funding” [34] (p. 15). Medium projects, on the other hand, are only available to organisations, whose projects should require up to EUR 300k of funding. Lastly, large projects have applications that require more than EUR 300k of funding, and they include collaborative projects and also other ideas that “will significantly benefit the broad news ecosystem” [34] (p. 15). The caveat to large projects is that it must include “at least one journalist on the team” [34] (p. 15), which apparently implies that none of the small or medium projects requires the involvement of news professionals in the proposals.

2.2. Methodology

As previously stated, this article aims to understand how Google’s DNI Fund works, and if in any case it can both help and constrict journalism practices in Europe. Therefore, we must formulate the following research questions:

- RQ1. How has Google distributed the DNI Fund money in Europe since 2016?

- RQ2. What kind of projects have been funded?

- RQ3. What is the profile of the companies that apply for funding?

With the intention of giving an answer to these questions, we have analysed the three DNI Fund reports published between 2017 and 2020. The last one of them is available at the Google News Initiative website (https://newsinitiative.withgoogle.com/dnifund/) (access on 15 January 2021). The other two are harder to find, although some online repositories have uploaded the file to their servers. After thoroughly revising each report, we have classified the data available, including the amount of money awarded, and organized in charts the different media funded over three years, marking chronologically every new country added to the project and all of the media outlets involved.

However, we would like to emphasize that the reports were not entirely specific regarding the nature of all the projects, the amount awarded, or the type of initiative carried on by each particular media outlet. The information that was missing has been collected manually through online searches related to the DNI Fund, such as news articles, blog posts or press releases. It is necessary to mention that this article was inspired by previous research carried on by Alexander Fanta from Netzpolitik.org [37], as well as the reports on Google’s transparency published in 2019 by the Tech Transparency Project [38]. Their insights have shed light on issues regarding the difficulties in our data collection and on the position of Google as a digital intermediary [39] in Europe.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Getting DNI’s Numbers

According to Google, between 2016 and 2017 there were 209 media projects funded by the DNI initiative. The United Kingdom (33) and Germany (28), followed by France (15), Spain (15) and Italy (14) were the countries with the most awarded projects. As Google claims in its reports, by the end of 2020, Germany (71), the United Kingdom (69) and France (61) were by far the great beneficiaries of this initiative. However, some numbers do not add up. For instance, in the 2017 report Google indicates that Austria had four different projects awarded. Despite explaining both Round 1 and 2 in detail for the first report, Google left out the two initiatives that participated in R1: Nimeh & Partners with a prototype project for monetization, and Der Standard (Standard Verlagsgesellschaft), with a medium project to identify negative emotions in online discourse. Table 2 shows the correct number of funded initiatives by round and country that we have compiled through the investigation.

Table 2.

Number of DNI projects awarded by country and year. Source: compiled by author.

The total number of projects presented by Google is 662. According to our research, there appear to be at least 17 missing projects from our database, which shows 646 as the total number of documented successful proposals. After investigating in detail all the names of the organizations involved, we realized that companies such as the Slovenian Event Registry or Honire Inovativne Informacijske Tehnologije, and others like the British Project for Study of the 21st Century or even Sky News, are nowhere to be found in the DNI website, although they do appear as part of the recipients in at least one of the three published reports. The missing data will be discussed in the following section.

As our evidence shows, the DNI Fund has continuously increased the number of European participants in each country; Cyprus (1) is the only exception to this statement as the Cyprus News Agency was their only accepted candidate in 2016–2017, and it has received no more money since the first initial round that year (although it appears in every report published by Google). Other countries, despite having smaller projects, have brought their media companies onto Google’s radar. Malta (1), for example, appears for the first time in 2020 with the participation of Mediatoday Co. Limited, a media company founded in 1999. Likewise, the two outlets in Estonia (AS Eesti Meedia, the biggest media group in the Baltic countries, and Õhtuleht Kirjastus AS, a media association) are present in one of the most recent rounds (5). Finally, it is worth mentioning that Lithuania (5), Luxembourg (2), Slovakia (4) and Slovenia (6) entered the DNI Fund in 2018 and have consistently increased their participation since then.

3.2. Footing the Bill

Although the reports only disclose information about the total amount awarded, we have managed to establish the full quantities involved in the three-year period based on the country destination. As it appears in Google’s report published in October 2017, the fund in 2016 was established in two different funding rounds. Table 3 shows both rounds, where we can see how countries such as Lithuania and Latvia participated only in the first one, while Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, and Slovakia appear in the second.

Table 3.

Total amount awarded to DNI projects in 2016 (R1 and R2) by country. Source: compiled by author.

The 2018 report also had a funding breakdown, although this time it does not separate the amount received in each round (Rounds 3 and 4 comprise all the projects awarded in 2017). In Table 4, we see a comparison between 2016 and 2017 in terms of funding. The difference between those years is shown in the third column.

Table 4.

Total amount awarded to DNI projects in 2016 and 2017 by country, and the difference between both years. Source: compiled by author.

Google’s final report was published in October 2020, and it summarized the total amount of money that was awarded by the DNI Fund Initiative. This is the first time that a disclaimer appears near the funding, which states: “6% of the DNI Fund went to knowledge sharing, reporting and overheads” [13] (p. 5). There are no further specifications as to what those activities involve, or whether the 6% is deducted by Google from the award. We also do not know if the recipient is obligated to carry out the dissemination activities with at least 6% of the final budget. Table 5 shows the awarded amounts by round throughout the whole DNI Fund initiative. Rounds 5 and 6, which took place in 2018 and 2019, respectively, have been calculated by deducting the total amount of the report for Rounds 3 and 4 from the total amount announced on the last report.

Table 5.

Total amount awarded to DNI projects in all the six rounds of funding by country. Source: compiled by author.

With respect to population, Table 6 X divides the total amount awarded to each country by its population, thereby obtaining a ratio that aims to simulate GDP in terms of media funding per inhabitant. Despite obtaining fewer funds through the DNI, Bulgaria and Romania are the two countries with the highest ratio, followed by Latvia and the Czech Republic.

Table 6.

Total amount awarded to DNI projects by country, population of each country and ratio as a simulation of GDP. Source: compiled by author.

3.3. Targeting Media Issues

The first DNI report thoroughly describes the purpose of the fund and goes into details about the nature of the projects and the most popular topics among successful applications. Those topics were clustered into seven categories: “Intelligence, Data Management and Workflow, Interface and Discovery, Next Journalism, Social and Community, Business Models, Distribution and Circulation” [34]. Table 7 shows the number of projects funded in each topic group in 2016 during Round 1 and Round 2.

Table 7.

Classification of the projects of Round 1 and Round 2 by topic. Source: compiled by author.

However, these categories disappear once we reach the report of 2018. Instead, Google breaks down the funding into four new categories: Battling Misinformation, Telling Local Stories, Boosting Digital Revenues, and Exploring New Technologies. The official document does not specify the nature of this change, so there is no easy way of relating the old and new brackets. Furthermore, the report does not give any more explanation regarding the distribution of the projects within the four different categories. There was no online information referring to this matter until the third and last report was published. According to Google, once the fund reached Round 6 more than half of the projects (52%) were aiming to explore new technologies, while concern about disinformation was a key aspect for 21% of the ventures [13]. Finally, 15% of the proposals focused on local journalism, and 12% were aiming to boost digital revenues [13]. However, we do not know if those percentages relate specifically to Round 6 or if they imply a full analysis of the whole DNI Fund.

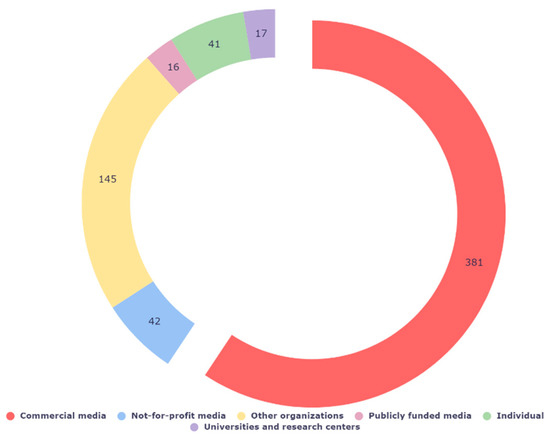

Regarding the profile of the companies that apply for funding, we can affirm that most of them are identified as “commercial media” (381). Universities and research centres (17) and publicly funded media (16) barely represent the 5% of the total of funded initiatives, followed by non-profit media (42) and individual participants (41). The latter have been counted as “independent actors” despite presenting or creating projects that involve or implicate existing media. Finally, in the category of “other organizations” (145) we have gathered different institutions that cannot be classified as media organizations, such as the Bulgarian company Damocles Analytics, which specializes in AI-driven political insights. The French private meteorological consultancy Meteo Consult also belongs to this category, as well as the German micropayment solution PayPeanuts or the Polish E-Kiosk. Figure 1 shows the different kinds of companies that have been funded by the DNI.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of the types of companies funded by the DNI (all rounds). Source: compiled by author.

3.4. Guess Who?

The last pages of every report are dedicated to all the funded organisations, classified by country. However, there have been some fluctuations between the three documents, and several media groups or companies have changed names or even disappeared. To give an example, Futurezone, an Austrian hightech, is presented at the end of the 2017 report as the developer of FutureBot, a framework for personalized news distribution via messenger. Yet, the Google News Initiative website shows Telekurier Online Medien as the awarded company, and the digital report establishes both companies as two very different initiatives. Belgium and its media group De Persgroep appear several times on the reports as well, with different names such as “De Persgroep Publishing” in 2017, or “De Persgroep Advertising and Mediahuis Connect” in 2018, as if they were separate entities or belonged to dissimilar subsidiaries of the company.

Secondly, it seems that Google easily overlooks the existence of companies that belong to the same parent corporation, such as the Czech Regi Radio Music, which belongs to the Lagardere Active group. Rasmus Nielsen Holdings presents a similar issue: PoliWatchBot, a medium project funded in Round 3, appears on the report as a proposal by the Danish newspaper Altinget. However, this company, as well as Mandag Morgen, which presented a project in Round 6, are not always identified as part of the media holding group. By appearing as independent companies, the list of recipients tends to be longer, and this is likely to mislead the reader.

The Spanish case also seems confusing: Grupo Prisa (Promotora de Informaciones S.A.), for instance, is a large media group with several subsidiaries around the country. In the reports, Google states that the Spanish media holding obtained funding for Rounds 1, 3, 4 and 6. However, Ediciones El País S.L. obtained money for a large project in 2016 (Round 1) regarding HD video, and another large project in Round 6 for a branded content inventory optimizer. El País belongs to Grupo Prisa, which Google never explains in any of the reports, nor publishes on the website. The same occurs with Prisa Inn (Round 3) or Prisa Radio (Rounds 1 and 6).

More examples include the 2020 report, where Sweden’s media appears, followed by 13 different companies funded by the DNI. Nonetheless, at least five of them belong to the Bonnier Group, such as Papereed, which presented in Round 5 a solution for automated and data journalism based on audio, or Kvällstidningen Expressen and its prototype in Round 3 (although this appears online as part of the Bonnier Group). Other initiatives like the ones brought by Bonnier Business Press or Bonnier News seem simpler to identify thanks to the name of the parent company already being present in the subsidiary.

Finally, our analysis includes individual proposals as part of the total projects accounted for. Sometimes they appear as duplicates, such as the German One Eighty, created by Victoria Schneider and awarded in Round 1. We have managed to create a full list of recipients (40) that were awarded with individual grants for prototype projects, as shown in Appendix A. All Rounds had at least four projects that benefited individuals: Round 1 awarded projects from the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Latvia and UK; Round 2 had proposals granted from Finland, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and the UK; prototypes participating in Round 3 were from the Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, Latvia and Slovakia; Round 4 had projects from Cyprus, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy and the UK; participants in Round 5 were from Austria, the Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, Romania and the UK; and Round 6 granted funding to Greek, Portuguese, Spanish and British projects.

3.5. Blurred Data

Gathering information to complete this research became a rather difficult task in terms of transparency. Previous investigations have shown that Google does not maintain a “centralized public repository of all of its journalism sponsorships” [38] (p. 2), and neither does it disclose the full size of each award. Almost 20% of the funded projects presented some issues regarding the total amount allocated to their proposals, and they have been categorized in our database as “not disclosed”. From the projects that did show a specific amount, 38.4% were listed as an undetermined range, matching the full size of the award for each category (EUR 50k in prototypes, EUR 300k for medium and up to EUR 1m in large projects).

Google keeps an active website that compiles most of the awarded companies and a brief description of each project. Unfortunately, it no longer includes all of the projects funded. We do not know, for instance, what happened to the French publishing house E2J2 that was present on the 2020 report because we have been unable to find any references by the DNI Fund to this project. The German regional newspaper Rhein-Zeitung is nowhere to be found, something that happens as well with Charged in the Netherlands, Honire in Slovenia, and the British Sky News, among others. Their presence in each year’s reports swells the ranks for each country, but there is no more information on the DNI website.

Last but not least, we must comment on the lack of consistency in the updates maintained by Google, which hindered our attempts to keep track of each project and classify them properly. For instance, there is no way of differentiating Round 1 from Round 2 projects in the DNI Fund online page. However, people like Danny Lein, founder of the software company Twipe, have published reports and articles online trying to gather as much information as possible regarding these funding opportunities [40].

4. Conclusions

After analysis of all the projects that played a part in the DNI Fund, we can secure and confirm once more that Google has a clear purpose and strategy to support media companies across Europe. Both the continuity of the funding program and the growing number of organizations involved are good examples of that. Following Dragomir [11], we argue that investigating whomever controls the money is a good lead to find out who controls the media. In this case, sustainability of news media companies involves not only finances, but also adapting to the shifting technological environment and taking advantage of collaboration with others outside their own organizations.

We can conclude that Google’s support has allowed all these media companies to develop closer relationships between digital technology and their true purpose of serving the public by producing news. This contribution could be particularly relevant in terms of company sustainability, because all the acquired abilities, new capacities and improved knowledge will remain within the company even after the awarded project comes to an end. For example, and according to our results, most of the companies that applied for funding delivered proposals related to core activities such as Next Journalism. However, technology-related issues were very important as well. Intelligence, Data Management and Flow, and Interface-related projects attracted considerable funding. Although exploring new business models is a big challenge for news media companies [22], we must understand that sometimes it is not the central thread for the industry.

The DNI Fund has created a significant network of media companies, institutions, and individuals that aim to collaborate to improve the media environment. Google’s economic and technological support to media companies, and what that implies for the industry, is a key element for developing further research. Some questions remain unanswered, such as how these initiatives influence media practices from a broader point of view, or what could be the long-term impact on European media policy. Likewise, the scarce information regarding the data publicly released by Google displays a warning message to Europe’s efforts for data transparency. Furthermore, we believe that more in-depth analysis of Google’s transparency will also contribute to creating a more accurate definition of credibility, sustainability [41] and a very much needed sense of accountability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G.-T. and C.S.-C.; methodology, C.G.-T. and C.S.-C.; formal analysis, C.G.-T. and C.S.-C.; data curation, C.G.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G.-T.; writing—review and editing, C.G.-T. and C.S.-C.; supervision, C.S.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 765140.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its appendix, and online https://data.mendeley.com//datasets/bmxzbw9hft/1https://data.mendeley.com//datasets/bmxzbw9hft/1 (accessed on 30 January 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Personal/individual grants awarded by the DNI Fund from 2016 to 2020.

Table A1.

Personal/individual grants awarded by the DNI Fund from 2016 to 2020.

| Personal/Individual Grants Awarded by the DNI Fund from 2016 to 2020 | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Sebastian Krause (Austria, Round 5) |

| 2 | Tomislav Simpovic (Cyprus, Round 4) |

| 3 | Jaroslav Benc (Czech Republic, Round 1) |

| 4 | Douglas Arellanes & Pete Haughie (Czech Republic, Round 3) |

| 5 | Jan Kesla (Czech Republic, Round 5) |

| 6 | Emmi Skytén (Finland, Round 2) |

| 7 | Atanas Tchobanov (France, Round 1) |

| 8 | Bryan Mcleod (Germany, Round 1) |

| 9 | Victoria Schneider (Germany, Round 1) |

| 10 | Daniel Mayer (Germany, Round 2) |

| 11 | Ben Shaw (Germany, Round 3) |

| 12 | Frank Westphal (Germany, Round 3) |

| 13 | Jakob Vicari (Germany, Round 3) |

| 14 | Aela Callan (Germany, Round 4) |

| 15 | Augustine Zenakos (Greece, Round 6) |

| 16 | David Koranyi (Hungary, Round 4) |

| 17 | Ernesto Díaz-Avilés (Ireland, Round 3) |

| 18 | Conor Molumby (Ireland, Round 4) |

| 19 | Carlo Strapparava (Italy, Round 2) |

| 20 | Alice Corona (Italy, Round 4) |

| 21 | Torlone Gianfranco (Italy, Round 4) |

| 22 | Valerio Bassan (Italy, Round 5) |

| 23 | Sultan Suleimanov (Latvia, Round 1) |

| 24 | Renars Liepins (Latvia, Round 3) |

| 25 | Adriana Homolova (The Netherlands, Round 2) |

| 26 | Alberto Pereira (Portugal, Round 2) |

| 27 | João Antunes (Portugal, Round 2) |

| 28 | Ricardo Lafuente (Portugal, Round 2) |

| 29 | Piotr Fedorczyk (Poland, Round 5) |

| 30 | Diogo Queiroz Andrade (Portugal, Round 6) |

| 31 | Inés Bravo (Portugal, Round 6) |

| 32 | Ozon Vasile Sorin (Romania, Round 5) |

| 33 | Ľubomír Šulko, Jana Tutková, Veronika Šoltinská (Slovakia, Round 3) |

| 34 | Carlos Ruano (Spain, Round 6) |

| 35 | Tomas Petricek (United Kingdom, Round 1) |

| 36 | James Durston (United Kingdom, Round 1) |

| 37 | Stuart Goulden (United Kingdom, Round 2) |

| 38 | Turi Munthe (United Kingdom, Round 4) |

| 39 | Angel Milev (United Kingdom, Round 5) |

| 40 | Tanya Cordrey (United Kingdom, Round 6) |

References

- Díaz-Noci, J. Cómo los medios afrontan la crisis: Retos, fracasos y oportunidades de la fractura digital. Prof. Inf. 2020, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavilhas, J. Nuevos medios, nuevo ecosistema. Prof. Inf. 2015, 24, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storsul, T.; Krumsvist, A.H. What is Media Innovation? In Media Innovations: A Multidisciplinary Study of Change; NORDICOM; University of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2013; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrís-Forés, J.A. La triple crisis de los medios de comunicación. Boletín Estud. Económicos 2012, LXVII, 533–548. Available online: https://bit.ly/3kzPxKP (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Küng, L.; Picard, R.; Towse, R. The Internet and the Mass Media; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, R. Strategic Responses to Media Market Changes; MMTC-JIBS: Jönköping, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Portilla Manjón, I.; Vara-Miguel, A.; Díaz-Espina, C. Innovación, modelos de negocio y medición de audiencias ante los nuevos retos del mercado de la comunicación. In Innovación y Desarrollo de Los Cibermedios en España; Eunsa: Pamplona, Spain, 2016; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R.K.; Selva, M. Five Things Everybody Needs to Know about the Future of Journalism; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism: Oxford, UK, 2019; Available online: https://bit.ly/2QKkmOa (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Schlosberg, J. The Mission of Media in an Age of Monopoly. Respublica. 2016. Available online: https://bit.ly/3jo9tRw (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Semova, D.J. Financing Public Media in Spain: New Strategies. Int. J. Media Manag. 2010, 12, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, M. Control the money, control the media: How government uses funding to keep media in line. Journalism 2018, 19, 1131–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecher, L. Digital News Initiative: €20 Million of Funding for Innovation in News. The Keyword. 2017. Available online: https://bit.ly/2Wygx5n (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Google. DNI Fund Annual Report. Google News Initiative. 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/3BiKQMd (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Nunes, A.C.B.; Canavilhas, J. Journalism Innovation and Its Influences in the Future of News: A European Perspective Around Google DNI Fund Initiatives. In Journalistic Metamorphosis; Vázquez-Herrero, J., Direito-Rebollal, S., Silva-Rodríguez, A., López-García, X., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera-Vivo, J.M. Panorámica de la convergencia periodística: Los caminos hacia la redacción Google. Prof. Inf. 2010, 19, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartise, I. “We Are all in this Together”: What Are the Challenges Google “Helps” Media Industries with? Master’s Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/3jodiGm (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Matsa, K.E.; Mitchell, A. 8 Key Takeaways about Social Media and News. Pew Research Center. 2014. Available online: https://pewrsr.ch/38iAMq3 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Grueskin, B.; Seave, A.; Graves, L. The Story so Far: What We Know about the Business of Digital Journalism; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Available online: https://bit.ly/3Dp20Ka (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Jukes, S. A perfect storm. In Journalism: New Challenges; Fowler-Watt, K., Allan, S., Eds.; Bournemouth University: Poole, UK, 2013; pp. 1–18. Available online: https://bit.ly/38ihTUk (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Tworek, H.J.S.; Buschow, C. Changing the rules of the game: Strategic institutionalization and legacy companies’ resistance to new media. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 2119–2139. [Google Scholar]

- Villi, M.; Picard, R.G. Transformation and innovation of media business models. In Making Media. Production, Practices and Professions; Deuze, M., Prenger, M., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sumelzo, N. La Sostenibilidad en el Sector Empresarial: Importancia de Los Distintos Grupos de Interés en el Proceso de Cambio a Sostenibilidad en el Sector Empresarial. Master’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica of Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2012. Available online: https://bit.ly/38kPSLP (accessed on 11 April 2020).

- Epstein, M.J. Making Sustainability Work: Best Practices in Managing and Measuring Corporate Social, Environmental, and Economic Impacts; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, T.A.; Benzie, M.; Börner, J.; Dawkins, E.; Fick, S.; Garrett, R.; Godar, J.; Grimard, A.; Lake, S.; Larsen, R.K.; et al. Transparency and sustainability in global commodity supply chains. World Dev. 2019, 121, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggie, J. Report of the special representative of the secretary-general on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises: Guiding principles on business and human rights: Implementing the united nations ‘protect, respect and remedy’framework. Neth. Q. Hum. Rights 2011, 29, 224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Glasser, A.; Oremus, W. Why Big Tech Companies Are Suddenly Trying to Save Local News. Slate. 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gD0IBC (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Xalabarder, R. Google News and copyright. In Google and the Law: Empirical Approaches to Legal Aspects of Knowledge-Economy Business Models; Lopez-Tarruella, A., Ed.; T.M.C. Asser Press: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 113–167. [Google Scholar]

- Chyi, H.I.; Lewis, S.C.; Zheng, N. Parasite or Partner? Coverage of Google News in an Era of News Aggregation. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2016, 93, 789–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantin, J.C.; Lagoze, C.; Edwards, P.N.; Sandvig, C. Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brake, D.R. The Invisible Hand of the Unaccountable Algorithm: How Google, Facebook and Other Tech Companies Are Changing Journalism. In Digital Technology and Journalism; Tong, J., Lo, S.H., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allyn, B.; Bond, S.; Lucas, R. Google Abuses Its Monopoly Power Over Search, Justice Department Says In Lawsuit. NPR. 2020. Available online: https://n.pr/3BqH1VE (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Scott, M. Europe Is Going after the Internet’s Business Model. A New One Is Urgently Needed. Politico. 2020. Available online: https://politi.co/3zvJZHw (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Bell, E. Who Owns the News Consumer: Social Media Platforms or Publishers? Columbia Journalism Review. 2016. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gLiHWl (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Google. DNI Fund Annual Report. Poder 360. 2017. Available online: https://bit.ly/3BpEdry (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Google. DNI Fund Annual Report. Google. 2018. Available online: https://bit.ly/3zwsOpn (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Servimedia. Google Firma Un Acuerdo Con Editores Europeos y Destinará 150 Millones Para La Innovación. El Economista. 2015. Available online: https://bit.ly/3t189HM (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Fanta, A. The Publisher’s Patron: How Google’s News Initiative Is Re-Defining Journalism. European Journalism Observatory. 2018. Available online: https://bit.ly/3kRMyxR (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Tech Transparency Project. Google’s Media Takeover. Tech Transparency Project. 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gJo0FW (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- González-Tosat, C.; Sádaba-Chalezquer, C. Digital Intermediaries: More than New Actors on a Crowded Media Stage. J. Media 2021, 2, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lein, D. Which Projects Have Been Funded by Google Digital News Initiative in the First Round? Twipemobile. 2016. Available online: https://bit.ly/3mXZGnN (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Marco-Fondevila, M.; Orive-Serrano, V.; Latorre-Martínez, P. Preparedness to Cope with an Unexpected Crisis. Lessons Learnt by Spanish Regional TV Broadcasting Management. JMM Int. J. Media Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).