1. Introduction

The United Nations Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development contains 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs). These goals are more or less formulated in anthropocentric terms, meaning that they are to be achieved for the sake of humans [

1]. This implies that the SDGs capture values that are supposed to be of particular interest to humans, such as ending poverty (SDG1) and hunger (SDG2), as well as securing health and wellbeing (SDG3) as well as quality education (SDG 4) [

2]. In effect, the SDGs are not taking the interests of non-human animals into direct consideration [

3].

Our aim in this paper is to critically analyse the anthropocentric assumptions that underlie the SDGs. We will argue that there are no good reasons to uphold these assumptions, and that the SDGs should therefore be reconsidered so that they take non-human animals into direct consideration. This means that the SDGs should also be achieved for the animals—and not only for humans.

It has been argued by others that animals should be taken into consideration in our ambitions to achieve the SDGs. For instance, some have argued that we should do so because it will help us achieve the SDGs—i.e., that animals have an important role to play in our pursuit of sustainability [

4,

5,

6]. Indeed, we need animals for pollination, for biodiversity, for food production, for eradicating poverty, for healthy oceans, etc. However, in this argument, animals are supposed to be merely

instrumental in the sense that the SDGs are understood so as to take animals into

indirect consideration—i.e., for humans. Hence, the argument acknowledges the anthropocentric formulation and interpretation of the SDGs.

Others have instead proposed that the animals should be considered in

their own right, and not merely because of their usefulness or relevance to humans [

3,

7]. However, it is seldom made explicit what are the moral grounds for such a direct consideration of animals, and it is moreover unclear how this inclusion should be made. It has been suggested that animals should be given their own SDG—considered as an additional

18th SDG on equal footing with the 17 SDGs that already exist—to be exclusively concerned with the welfare, freedom and rights of animals [

8]. Although this proposal is interesting, its argumentative support is scarce. Moreover, as we will show in this paper, an additional SDG is not needed since a reinterpretation of the existing SDGs suffices for a direct inclusion of the animals in the SDG framework. In other words, we argue that taking animals into direct consideration is consistent with the formulations of the SDGs as they stand.

As this suggests, we will in this paper present a new—alternative—way in which animals could be taken into direct consideration in the SDG framework. We shall moreover provide some arguments for why they should be considered as such. We think that our proposal is simpler and better grounded than the proposals made by others in the debate. By considering the existing SDGs as being directly relevant for animals, the concern for animals would also be more integrated than if they were formulated in a separate SDG.

It should be noted that there are many different animals, and many different usages of the term “animals”. We shall throughout this paper focus on sentient animals, for reasons to be presented below. Hence, whenever we use “animals” we will have sentient animals in mind. By “sentient” we shall mean having the capacity to feel pain and pleasure. As this implies, our paper will not provide an argument for the inclusion of non-sentient animals in the SDG framework.

The disposition of the paper is as follows. In

Section 2, we explicate the main implicit assumptions that underlie the widespread anthropocentric understanding of the SDGs. In

Section 3 and

Section 4, we show that there are no good reasons for upholding these assumptions. In

Section 5, we show how we could take animals into direct consideration through a reinterpretation of the existing SDG framework. In

Section 6, we summarise and conclude that the choices we make regarding which means we undertake in order to achieve the SDGs should be sensitive to the interests of non-human animals.

2. The Assumptions behind the Anthropocentric Perspective on the SDGs

There has been an increased awareness during the last half century or so, of the fact that many animals are sentient, as well as about how animals are treated in modern farming industry, in pet animal handling and in the exploitation of their habitats. Moreover, the interest in animal ethics has increased significantly. Most influentially, Peter Singer and Tom Regan called for reflection on how we handle animals in their commonly edited book from 1976 — a compilation of old and new philosophical elaborations on human responsibility and animal sentience [

9]. This was well timed with the general ‘wake up call’ formulated by Ruth Harrison in her book Animal Machines (1964) on factory farming [

10,

11]. This was in turn leading to the Brambell report and formulation of the ‘five freedoms’—which has been influential until today’s legislation in the EU [

12,

13,

14]. The animal ethics discourse has continued ever since, calling for a shift from anthropocentrism to sentientism (less frequently, but also called pathocentrism, zoocentrism and psychocentrism)—considering all sentient beings for their own sake. An increasing number of citizens are vegetarians or vegans, for the sake of animal welfare and animal rights, or for climate reasons [

15,

16]. However, society in general remains anthropocentric. This human-centeredness is mirrored in the current SDG framework, with the aim of improving the situation for those affected by starvation, water scarcity, etc.

In line with this, and as mentioned above, the SDGs are typically formulated and interpreted in anthropocentric terms. This becomes clear when reading the descriptions of the respective SDGs and their targets, as well as the reasons behind why it is important to achieve a sustainable future [

1,

2]. However, the motivation behind this anthropocentric perspective is seldom made explicit in the debate. Instead, the anthropocentric perspective appears to be

structural in the sense that it comes embedded in people’s general worldviews. Nevertheless, the anthropocentric perspective on the SDGs can be based on some more or less implicit assumptions, that are widespread among politicians as well as the public and the research community [

17]. In particular, we found that the two following implicit assumptions are crucial in this context:

First implicit assumption: The SDGs cannot be interpreted so as to apply directly to non-human animals.

Second implicit assumption: The SDGs should not be reformulated so as to be applicable directly to non-human animals.

The first implicit assumption is descriptive, thus saying something about the actual applicability or relevance of the SDGs. The plausibility of this assumption could be supported by the fact that many aspects of sustainability appear to be irrelevant for non-humans, such as achieving quality education (SDG 4), achieving affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), and achieving economic growth and decent work (SDG 8).

The second implicit assumption is normative, thus saying something about what would be a desirable applicability of the SDGs. The motivation behind this assumption seems to come from the idea that the overarching aim of sustainability is to end human hunger (SDG 2), to safeguard human health and wellbeing (SDG 3), to reduce inequality between humans (SDG 10), to fight climate change for humans (SDG 13), and so on.

Although these assumptions may explain why animals are typically excluded in the pursuit of sustainability, they do not automatically justify such an exclusion. Below, we will examine the extent to which they can justify an exclusion of animals in the SDG framework. In doing so, we will assess the potential reasons there could be for maintaining these assumptions.

3. Why Can the SDGs Not be Directly Applicable to Non-Human Animals?

In this section, we will question the first implicit assumption: that the values that are supposed to be protected by the SDGs are directly relevant for humans only, and that it is therefore impossible to apply them directly to non-human animals.

It should be noticed that the first implicit assumption does

not exclude that the SDGs can be

indirectly relevant for non-human animals. As mentioned above, several authors have argued that achieving the SDGs will become easier, were we to take animals into account, and that such an achievement would have implications for non-human animals [

4]. For instance, achieving responsible production and consumption (SDG 12), or peace and justice (SDG 16) will be of indirect relevance to non-human animals. Even if these SDGs are not intended to be achieved

for animals, achieving them will certainly

affect animals in a positive way. However, the assumption under scrutiny in this section implies that the SDGs are formulated more or less

exclusively for humans. If achieving the SDGs will have positive effects for animals, then that is a mere (although welcome) side effect.

As we see it, there are mainly two reasons to think that the SDGs cannot be interpreted so as to be directly applicable to non-human animals. We will now assess them in turn.

3.1. Some Aspects of the SDGs Are Relevant for Humans Only

One reason to think that the SDGs cannot be applicable to non-human animals is that some aspects of sustainability, and hence some SDGs, appear to be relevant for all and only humans. As mentioned above, it does not seem to make much sense to provide animals with qualitative education (SDG 4), or clean and affordable energy (SDG 7). Nor does it seem to make much sense to provide animals with economic growth and decent work (SDG 8).

Against this reasoning, however, it might be noticed that not all SDGs are relevant to all humans in the first place. For instance, it does not appear to make much sense to provide quality education (SDG 4) to those humans who suffer from irreversible brain damages or grave mental illnesses, or to provide decent work (SDG 8) to elderly or those who are so physically incapacitated that they cannot really perform any work. Of course, one might want to argue that we could understand the SDGs differently depending on the capacities of the individual human being. Hence, we might want to say that something could count as “education” or “work” for one person even if it would not count as such for someone else. However, if we take this argumentative route, then we should be open to the possibility of understanding different SDGs differently also depending on whether we have humans or non-human animals in mind—since it is possible to understand “education” and “work” in ways that would make sense also for non-human animals, e.g., dogs “employed” in police or military forces, donkeys and cows used at the fields, or animals engaged in tourism. We could, for instance, understand it as relevant to require a “meaningful activity” and decent working conditions which could be interpreted in a way that applies to non-human animals as well. Hence, if an SDG needs not be applicable to all humans, but rather in relation to specific capacities or situations, it opens up for an inclusion of non-human animals.

One could perhaps argue that even if education in terms of passing knowledge and inspiring complex thinking (as opposed to training, for instance) may be irrelevant for some human

individuals, it is certainly relevant to humans

as a species. The same cannot be said about animal species. However, one can note that even if some SDGs are

unavoidably human-centred, in the sense that there is

no way in which they can be understood so as to be directly relevant for non-humans, it does not follow that

no SDG is directly relevant for non-humans. Obviously, no hunger (SDG 2), as well as health and wellbeing (SDG 3), can be understood in non-anthropocentric terms, hence denoting the hunger or health and wellbeing of non-human animals. Likewise, clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), climate action (SDG 13), life below water (SDG 14), and life on land (SDG 15), can also be seen as directly relevant for non-human animals. There is thus no inherent inconsistency between the SDG framework as such and an inclusion of animals in its scope of direct considerability. As we shall get back to in

Section 5, there is nothing strange about a set of SDGs some of which are applicable to all animals in general (i.e., human and non-human alike) and some of which are applicable to humans only.

3.2. Non-Human Animals Cannot Themselves Play any Part in the Achievement of the SDGs

A separate reason to think that the SDGs cannot be applied to animals directly stems from the fact that animals cannot themselves play any part in the achievement of the SDGs. In other words, the duties that are implied by the SDGs cannot be undertaken by any non-human animal. Only humans can undertake the tasks that come with the SDGs. As the idea goes, to deserve something one must serve something. In the present context, this means that if one is to be taken into direct consideration, one must be able to take others into such consideration. If this is true, then the SDGs are not applicable to non-human animals.

However, this argument highlights a classical ethical discussion on whether there is a correlation between duties and rights. What is more, the argument conflates the concept of a

moral agent with that of a

moral patient [

18]. A moral agent is someone with the capacity to make decisions and perform moral actions. This means that a moral agent is someone with the capacity to behave intentionally with an understanding of norms that govern right action. In other words, a moral agent can perform right and wrong actions. Typically, adults and cognitively well-functioning human beings count as moral agents, while infants, the senile, the severely cognitively disabled, or non-human animals, do not. Suffice it to say that a moral agent can have

duties towards others.

A moral patient, on the other hand, is an entity (typically an individual) that moral agents should take into

direct consideration when they act. In other words, a moral patient possesses

moral standing. It should be distinguished between

indirect and

direct moral standing [

10]. To possess indirect moral standing implies being of relevance for the sake of someone else. For instance, my computer possesses indirect moral standing, and should thus be taken into consideration (although indirectly) when others are acting, since it is relevant

for me. However, it does not possess direct moral standing, since actions should not be performed for the computer’s own sake. You and I, however, possess direct moral standing, since others’ actions should take us into direct account. This means that we should be treated (at least in part)

for our own sake. Suffice it to say that a moral patient has certain (basic or non-basic)

rights to be treated in certain ways [

19].

Having made this distinction, we can see that some SDGs are agent-centred in the sense that they are formulated in terms of duties that moral agents have to safeguard certain states of affairs—such as responsible production and consumption (SDG 12), climate action (SDG 13), and partnership for the goals (SDG 17). However, we can also see that some SDGs are patient-centred in the sense that they are formulated in terms of rights that moral patients have to certain goods—such as food (SDG 2), and clean water and sanitation (SDG 5). This also suggests that an individual may be worthy of direct moral consideration in the SDG framework, even if that individual does not qualify as a moral agent. Therefore, it does not make sense to say that the SDGs in general are not applicable to non-humans just because non-humans do not count as moral agents.

The conclusions from this section are that neither the view that (i) some SDGs are particularly relevant for humans, nor the view that (ii) animals do not count as moral agents, manage to qualify as a reason in support of the first implicit assumption: that the SDGs cannot be directly relevant for non-human animals. Rather, this suggests that some SDGs can be directly applicable, and so are of relevance, to animals. In effect, the first implicit assumption fails to support the anthropocentric reading of the SDGs.

Of course, it might still be argued that the SDGs should not be interpreted so as to be directly relevant for non-human animals, even if they could be. This is indeed what the second implicit assumption is about. To that we shall now turn.

4. Why Should the SDGs Not be Reconsidered so as to Directly Apply to Animals?

The second implicit assumption, underlying the prevailing anthropocentric understanding of the SDGs, has it that it would be morally unapt to reconsider the SDGs in order for them to be more directly applicable to non-human animals. As mentioned above, this is a normative assumption about the desirability of the formulation (or interpretation) of the SDGs.

One reason to think that the second implicit assumption is justified, would build on the first implicit assumption (that the SDGs cannot be interpreted so as to concern animals directly) in combination with the widely accepted principle that “ought” implies “can” (which means that we ought to do things only if we can do them). In the present context, this combination implies that if we cannot include animals in the SDG framework, then it is not the case that we ought to include them. As we saw in the previous section, however, we can take animals into direct consideration in (at least some of) the SDGs, for which reason the argument fails.

However, even if we can interpret the SDGs so as to include a direct concern for animals, it does not follow that we should do so. There might indeed be independent reasons for not doing so. Below, we will assess what we suggest to be the two most potential reasons in such a respect: first, that animals do not possess direct moral standing; and, second, that (in case animals would possess direct moral standing) they do not possess the same degree of moral standing as humans.

4.1. Animals Do Not Possess Direct Moral Standing

One of the arguments made in

Section 3 was that moral agency is not required in order to be taken into direct consideration in the SDG framework—it suffices that one is a moral patient. However, we have not yet argued that non-human animals count as moral patients. If animals lack direct moral standing, in the sense that they do not count as moral patients, then that would be a reason for not taking them into direct consideration in the SDGs.

It is easy to understand why artifacts (such as cars, mobile phones, and houses) as well as many natural things (such as stones, leaves, and molecules) should not be taken into direct consideration in the sustainability framework. It would make no sense to achieve the SDGs for

their sake. It is not that easy, however, to show that non-human animals belong to this category of entities. To the contrary, it is quite easy to show that non-human animals, in virtue of their capacities to experience pleasure and pain, belong to the category of entities that possess moral standing [

18,

19,

20].

Interestingly, it is very hard to show

why—or in virtue of

what—humans would, whilst animals would not, possess direct moral standing [

19]. This has to do with the fact that whatever feature we take to be morally relevant for having direct moral standing, we will either find that

not all humans possess this feature, or that

not only humans possess it. If we refer to a high intellectual capacity, for instance, then it is the case that not all human beings possess it. Infants, the senile, and the severely cognitively disabled do not—since they are not sufficiently intelligent or rational. If we refer to sentience, on the other hand, then it is clear that even though all humans do possess it, so too do many non-human animals—since even non-human animals are sentient. Ethicists generally agree that whatever feature we take to be relevant for the possession of moral standing, this feature does not have to do with being a human

as such [

21].

Most ethicists adhere to the latter—

sentientist—view on moral standing, according to which being sentient is what matters crucially [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. According to this view, an individual is, basically, worthy of direct moral consideration if that individual is capable of experiencing pleasure or pain. This view can explain why infants, the senile, and the severely cognitively disabled are included in the sphere of moral concern, despite the fact that they do not count as moral agents. Since many non-human animals are sentient too, they also possess direct moral standing.

Let us therefore turn to the second reason for thinking that the SDGs should not be reinterpreted so as to include a concern for animals directly.

4.2. Animals Do Not Possess the Same Degree of Moral Standing as Humans

Even if sentientism is the correct view on moral standing, and all sentient beings thus possess direct moral standing, it does not follow that all sentient beings—i.e., humans and animals—are worthy of

equal moral standing. In other words, the “worthiness” of direct moral considerability might come in degrees [

24] (p. 41). Accordingly, it could be argued that humans are nevertheless morally

superior to non-human animals, and that the SDGs should

therefore take humans into consideration exclusively. This is in line with the view, noted in

Section 1 and

Section 2, that the overarching aim of sustainability is to end

human hunger (SDG 2), to safeguard

human health and wellbeing (SDG 3), to reduce inequality between

humans (SDG 10), to fight climate change for

humans (SDG 13), and so on.

The rationale behind this view comes from a distinction that is often made in animal and environmental ethics, between

egalitarian and

hierarchical versions of biocentrism (where biocentrism is the view that all and only living organisms possess direct moral standing) in combination with the robust arguments against egalitarian biocentrism in favour of hierarchical biocentrism [

25]. For one such argument, egalitarian (but not hierarchical) biocentrism implies that it is equally wrong to kill a wildflower as it is to kill a human being [

26]. This is utterly counterintuitive, since there are more moral values to lose by killing a human than by killing a wildflower—even though both would possess direct moral standing. While both the wildflower and the human are alive and have needs, only the human have desires, feelings, plans, knowledge, and relations to others [

27] (p. 189). The same kind of reasoning may be applied to distinguish between humans on the one hand and non-human animals on the other. Hence, it might be argued that even if humans and animals both possess direct moral standing, there is more to lose by killing a human than by killing an animal.

We shall not dig deeper into this interesting philosophical issue, but rather accept for the sake of argument that animals are not morally equal to humans. Since, even if humans are morally superior to animals, it does not follow that animals should not be taken into direct consideration within the SDG framework. Interestingly, there is nothing that precludes that some SDGs should be considered as directly relevant for animals in general (i.e., humans and non-humans alike), yet some of the SDGs are relevant for humans only.

The lesson to learn from this section is that neither of the views that (i) animals lack moral standing, and (ii) humans are morally superior to animals, manage to qualify as reasons in support of the second implicit assumption: that the SDGs should not be considered directly for the sake of non-human animals. In the next section, we will show how animals could be taken into direct consideration within the SDG framework, while maintaining a focus on humans.

5. How to Take Animals into Direct Consideration within the SDG Framework

The way in which we will include a direct concern for the animals within the SDGs is by making a division between human-centred SDGs (concerning only humans) and sentience-centred SDGs (concerning all sentient animals, human and non-human alike), as it were. We will base this division on two observations. The first and quite obvious observation is that all SDGs come with an assumption about something being valuable; the second observation is that the different values of the different SDGs are of different relevance to humans and non-humans. We will now clarify these observations in turn.

5.1. The First Observation

All SDGs come with a more or less implicit evaluative assumption—i.e., regarding what is good or bad. Indeed, this is what makes a goal a goal: that it is valuable, desirable, or worthy of being achieved. Even if this might appear to be obvious to some, we shall here explicate these assumptions (also for the reason that it will simplify the reasoning that follows). A rough explication of the SDGs and their respective evaluative assumptions may look like this:

SDG 1—No poverty: poverty is a bad thing, and it would be a good thing if poverty were ended everywhere.

SDG 2—Zero hunger: hunger is a bad thing, and it would be a good thing if there would be no hunger in the world.

SDG 3—Good health and wellbeing: health and wellbeing are good things that should be promoted.

SDG 4—Quality education: Equitable quality education is a good thing that should be promoted.

SDG 5—Gender equality: Gender equality is a good thing, hence women and girls should be empowered.

SDG 6—Clean water and sanitation: Clean water and sanitation are good things that should be ensured.

SDG 7—Affordable and clean energy: Affordable and clean energy is good and should be made accessible.

SDG 8—Decent work and economic growth: Decent work and economic growth are good things that should be promoted.

SDG 9—Industry, innovation and infrastructure: Industry, innovation and infrastructure are good things that should be promoted.

SDG 10—Reduced inequalities: Inequality is bad and should thus be reduced both within and between countries.

SDG 11—Sustainable cities and communities: Sustainable cities and communities are good and should therefore be constructed and safeguarded.

SDG 12—Responsible consumption and production: It is good to produce and consume things in sustainable ways, and we therefore have a responsibility to do so.

SDG 13—Climate action: Climate change is a bad thing, and we should take action to ensure climate stability.

SDG 14—Life below water: Sustainable oceans, seas and marine resources are valuable and should be conserved.

SDG 15—Life on land: Forests, ecosystems, and biodiversity are good things that should be protected.

SDG 16—Peace, justice and strong institutions: Peace and justice are good, and strong institutions should be promoted for their sake.

SDG 17—Partnerships for the goals: Partnership and participation in the work with the SDGs is valuable and should be ensured.

Having spelled out the SDGs and their respective evaluative assumptions, we may now turn to the second observation.

5.2. The Second Observation

The different values of the different SDGs are of different relevance to humans and non-humans. Given the current anthropocentric perspective on the SDGs, it is not surprising that the values of all SDGs are (more or less) directly relevant to humans. As this implies, there is no SDG that is not directly relevant to humans. Moreover, some things, such as poverty (SDG 1), education (SDG 4), gender equality (SDG 5), affordable energy (SDG 7), work and economic growth (SDG 8), industry and infrastructure (SDG 9), and partnership for the goals (SDG 17) concern values that are, quite obviously, human centred. Hence, these values are not directly relevant to non-human animals, for which reason these SDGs should be achieved for the sake of humans.

However, some other values, such as zero hunger (SDG 2), good health and wellbeing (SDG 3), clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), climate action (SDG 13), life below water (SDG 14), and life on land (SDG 15), are directly relevant also to animals. Having enough food, good health, access to clean water, a stable climate, healthy oceans, prosperous forests, and so on, matters directly to animals as well. It could also be argued that reduced inequalities (SDG 10) as well as peace and justice (SDG 16) are in general sentience-centred, since justice and equality matter not only within the human species but also between different animal species. Just because one species (or individual) is stronger than other species (or individuals) does not give the stronger one a right to dominate or exploit the relatively weaker ones, for example.

Moreover, one could consider sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), and responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), as directly relevant for animals. A city or community that is not inclusive with respect to non-human animals, in the sense that its construction would be discriminating towards these animals, would not be fully sustainable. Likewise, consumption or production patterns that do not consider its effects on non-human animals would not be fully responsible either.

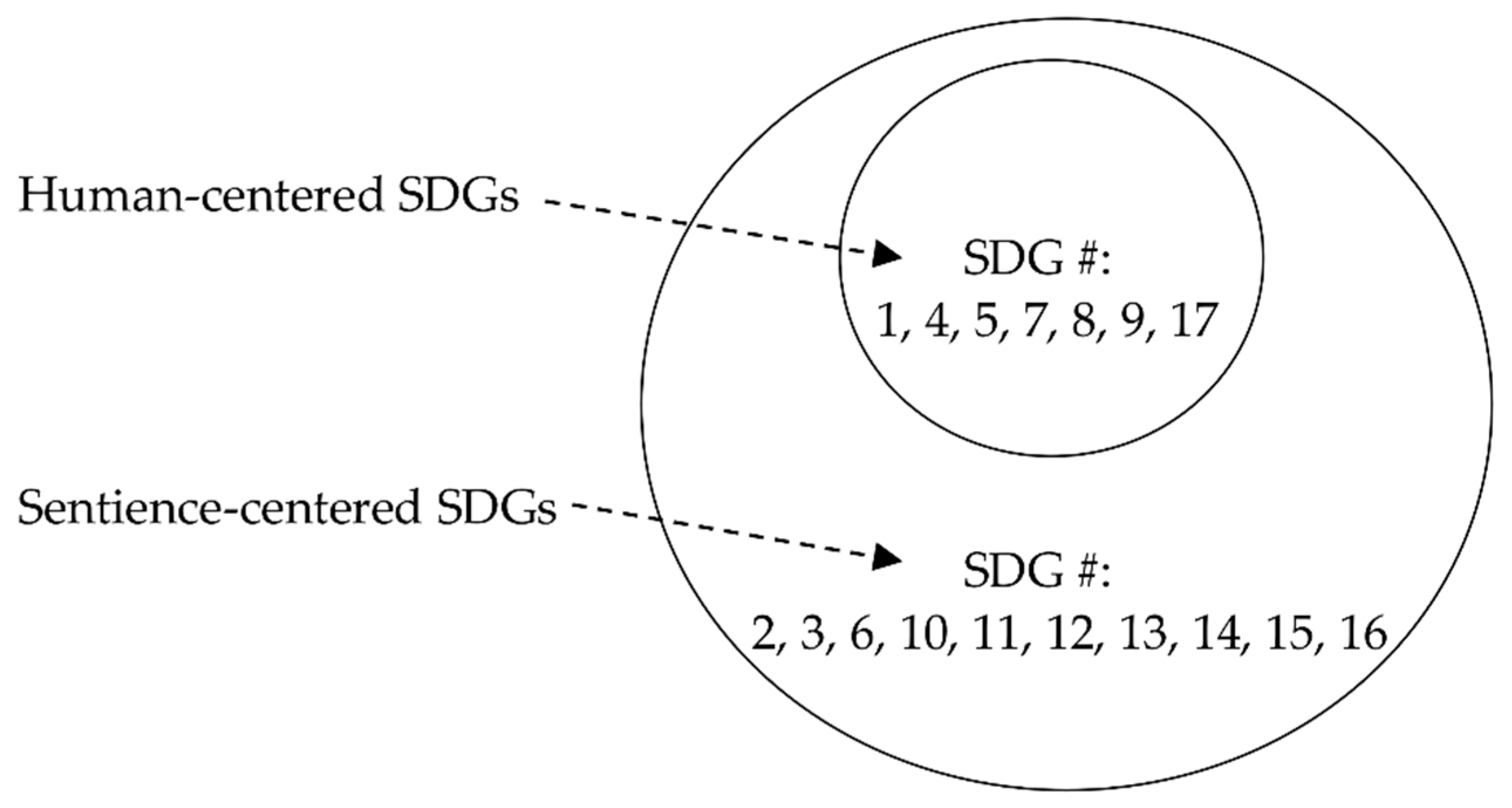

This suggests that the following division can be made between human-centred SDGs and sentience-centred SDGs:

Since human beings are sentient beings, this division may be illustrated by a Venn diagram as follows (

Figure 1), where the set of human-centred SDGs constitutes a subset of the sentience-centred SDGs:

Having made this division, we considered it evident that an inclusion of the animals in the SDG framework is neither impossible, nor implausible. Rather, non-human animals deserve to be taken into direct consideration where doing so is reasonable—i.e., in the sentience-centred SDGs. In other words, these SDGs should be achieved for animals as well. This moreover means that measures undertaken in order to achieve these SDGs must also take into direct account the effects on non-human animals, and not only their effects on humans. Furthermore, in light of the current SARS COVID-19 pandemic and its origin in animals, as well as the growing concern for bacterial resistance to antibiotic treatment (also shown to be transferable between species), one can easily see additional arguments for including animals in the strive for fulfilling the SDGs. This line of reasoning also highlights questions related to a potential difference in responsibility between domestic and wild animals (which remains to be elaborated in a future paper) [

19].

Moreover, it is interesting to note that the SDGs’ scope of direct moral considerability could be further extended so as to be relevant also for non-sentient parts of nature—such as plants, forests, oceans, ecosystems, etc. For instance, SDG 14 (life below water) and SDG 15 (life on land) would be of direct relevance to such entities. Whether such an inclusion should be made depends on the moral standing of such entities, which is a question beyond the scope of this paper.

6. Conclusions

This paper has argued that (i) it is possible to understand several of the SDGs as goals that matter directly for non-human animals, and (ii) non-human sentient animals deserve to be taken into direct consideration in the interpretation of these goals. It has thus been shown that it is possible to understand (at least some of) the SDGs as goals that should be achieved for the sentient animals too.

We think that these findings are interesting for several reasons. First, and most generally, it adds fuel to the trend of including the sentient animals in the SDG framework. Second, it provides a solid ethical argumentation for

why this inclusion should be made. Third, it provides a new alternative proposal for

how this inclusion could be made. Surely, it remains to be answered exactly which animals are included in the domain of sentient beings. Presumably, nematode worms are not included, while the great apes, elephants, cetaceans—and other candidates for nonhuman personhood—most certainly are. However, we do not seek to settle whether all and only mammals, or all and only vertebrates, etcetera, are included in this domain. We only intended to say something about

which features are relevant for moral status, not

which beings possess these features. We are aware that this may have implications for whether or not policy makers will listen to the arguments we have made. Indeed, adapting the SDGs to encompass a limited set of non-human persons would be a completely different undertaking to adapting SDGs to encompass all vertebrates plus some invertebrates, for instance. Still, this problem is a problem for

all sentientist views (including that of Visseren-Hamakers [

8]). Moreover, it is not per se a problem for normative ethicists to answer, but rather for biologists, ethologists and other empirical scientists who study animals and their various capacities that might be ethically relevant.

Nevertheless, we have not said anything about the practical implications of an inclusion of sentient animals in the SDG framework. There are thus several concrete questions that remain to be answered. For instance, would the inclusion of sentient animals imply that they could no longer be eaten as they are today, and that the world should therefore move towards plant or insect-based diets? Or could they still be eaten if their welfare was good, or if there are no other alternative food resources available to humans? Would including animals in the SDGs have any implications for wildlife management and conservation? We would answer all these questions in the affirmative, yet we are aware that these issues need more thought. However, providing those thoughts lies outside the scope of this paper.

One might still object that the inclusion of animals in the SDG framework risks leading to clashes between human interests and animal interests. In response to this, it should be noted that the mere fact that a complication or risk of conflict appears, due to an inclusion of a group of individuals in a framework, does not constitute an argument against such an inclusion. If that was not the case, we would have reason to not include all humans in the SDG framework, or all dimensions of sustainability (i.e., social, ecological, and economic), since there are similar types of conflicts between different human beings as well as between different dimensions of sustainability. However, since we do have reasons to include all humans in our pursuit of sustainability, and all dimensions thereof, the complicating or conflict-inducing factor is not crucial in this respect.

Nevertheless, it is a fairly widespread view that measures undertaken in order to achieve one SDG (e.g., SDG 8: decent work and economic growth) must not jeopardise the achievement of other SDGs (e.g., SDG 13: climate action). An implication of the arguments given in this paper is that a measure undertaken in order to achieve the SDGs must take into direct account also its effects on non-human animals.