Preferences of German Consumers for Meat Products Blended with Plant-Based Proteins

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Overview about Consumer Attitudes and Preferences Relating to Meat and Meat Alternatives

2.1. Sensory

2.2. Environment

2.3. Animal Welfare

2.4. Health

2.5. Meat Attachment Questionnaire (MAQ)

2.6. Food Neophobia Scale (FNS)

2.7. Product Familiarity Meat Substitutes

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Preferred Buying Location and Buying Frequency of Organic Respectively Free Range Meat

3.3. Applied Scales—FNS and MAQ

3.4. Direct Questions about the Consumption of Meat Substitutes

3.5. Comparison Task Meathybrid vs. Meat

- healthier?

- tastier?

- better for the environment?

- better for animal welfare?

3.6. Logistic Regression Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Preferred Buying Location and Buying Frequency of Organic Respectively Free Range Meat

4.2. Meat Attachement Questionnaire (MAQ) and Food Neophobia Scale (FNS)

4.3. Consumption of Substitutes

4.4. Comparison Meat vs. Meathybrid

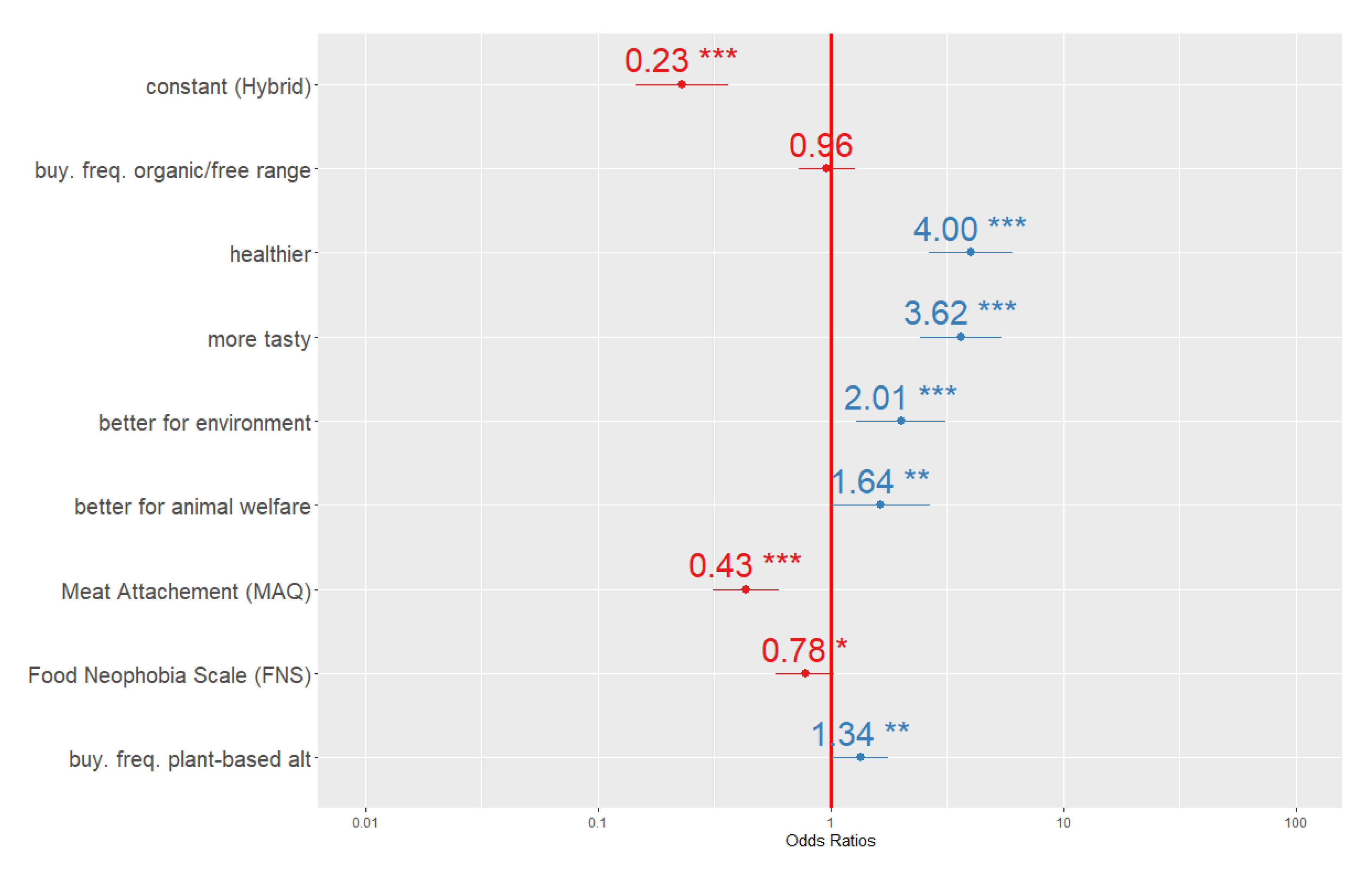

4.5. Multinomial Logit Regression Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Attribute | Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| gender | male | 245 | 49.0 |

| female | 255 | 51.0 | |

| federal | Baden-Württemberg | 66 | 13.2 |

| state | Bavaria | 75 | 15.0 |

| Berlin | 22 | 4.4 | |

| Brandenburg | 15 | 3.0 | |

| Bremen | 5 | 1.0 | |

| Hamburg | 10 | 2.0 | |

| Hesse | 37 | 7.4 | |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 10 | 2.0 | |

| Lower Saxony | 50 | 10.0 | |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 114 | 22.8 | |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 20 | 4.0 | |

| Saarland | 5 | 1.0 | |

| Saxony | 26 | 5.2 | |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 15 | 3.0 | |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 15 | 3.0 | |

| Thuringia | 15 | 3.0 | |

| age | <25 years | 65 | 13.0 |

| 25–34 years | 66 | 13.2 | |

| 35–44 years | 99 | 19.8 | |

| 45–54 years | 84 | 16.8 | |

| 55–64 years | 73 | 14.6 | |

| >64 years | 113 | 22.6 | |

| education | no school qualifications | 2 | 0.4 |

| still at school | 4 | 0.8 | |

| junior high diploma | 88 | 17.6 | |

| high school diploma | 193 | 38.6 | |

| university-entrance diploma | 105 | 21.0 | |

| bachelor or master degree | 89 | 17.8 | |

| other degree | 19 | 3.8 | |

| monthly net | no income | 26 | 5.2 |

| income | less than 500 € | 30 | 6.0 |

| 500 € up to 1000 € | 46 | 9.2 | |

| 1000 € up to 1500 € | 95 | 19.0 | |

| 1500 € up to 2000 € | 92 | 18.4 | |

| 2000 € up to 2500 € | 69 | 13.8 | |

| 2500 € up to 3000 € | 57 | 11.4 | |

| 3000 € up to 3500 € | 27 | 5.4 | |

| 3500 € up to 4000 € | 25 | 5.0 | |

| 4000 € or more | 33 | 6.6 | |

| household | 1 | 121 | 24.2 |

| size | 2 | 207 | 41.4 |

| 3 | 92 | 18.4 | |

| 4 | 55 | 11.0 | |

| 5 | 20 | 4.0 | |

| 6 | 4 | 0.8 | |

| >6 | 1 | 0.2 |

Appendix B

References

- Max Roser, H.R.; Ortiz-Ospina, E. World Population Growth. Our World Data 2013. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/world-population-growth (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- De Boer, J.; Schösler, H.; Aiking, H. “Meatless days” or “less but better”? Exploring strategies to adapt Western meat consumption to health and sustainability challenges. Appetite 2014, 76, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallström, E.; Röös, E.; Börjesson, P. Sustainable meat consumption: A quantitative analysis of nutritional intake, greenhouse gas emissions and land use from a Swedish perspective. Food Policy 2014, 47, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richi, E.B.; Baumer, B.; Conrad, B.; Darioli, R.; Schmid, A.; Keller, U. Health risks associated with meat consumption: A review of epidemiological studies. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2015, 85, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroeze, C.; Bouwman, L. The role of nitrogen in climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, W.; Kros, J.; Reinds, G.J.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Quantifying impacts of nitrogen use in European agriculture on global warming potential. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erisman, J.W.; Galloway, J.; Seitzinger, S.; Bleeker, A.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Reactive nitrogen in the environment and its effect on climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Profeta, A.; Hamm, U. Do consumers care about local feedstuffs in local food? Results from a German consumer study. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 88, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, M.; de Boer, I.J.M. Comparing environmental impacts for livestock products: A review of life cycle assessments. Livest. Sci. 2010, 128, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Wirsenius, S.; Henderson, B.; Rigolot, C.; Thornton, P.; Havlík, P.; De Boer, I.; Gerber, P. Livestock and the Environment: What Have We Learned in the Past Decade? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2015, 40, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiking, H. Future protein supply. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Prass, N.; Gollnow, S.; Davis, J.; Scherhaufer, S.; Östergren, K.; Cheng, S.; Liu, G. Efficiency and Carbon Footprint of the German Meat Supply Chain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 5133–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Durlinger, B.; Koukouna, E.; Broekema, R.; Van Paassen, M.; Scholten, J. Agri-footprint 4.0. In Technical Report; Blonk Consultants: Gouda, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schösler, H.; de Boer, J.; Boersema, J.J. Can we cut out the meat of the dish? Constructing consumer-oriented pathways towards meat substitution. Appetite 2012, 58, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandin, T. Welfare Problems in Cattle, Pigs, and Sheep that Persist Even Though Scientific Research Clearly Shows How to Prevent Them. Animals 2018, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dawkins, M. Animal Suffering, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1980; p. 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sans, P.; Combris, P. World meat consumption patterns: An overview of the last fifty years (1961–2011). Meat Sci. 2015, 109, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Schmidt, U.J. Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: A review of influence factors. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neville, M.; Tarrega, A.; Hewson, L.; Foster, T. Consumer-orientated development of hybrid beef burger and sausage analogues. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Attached to meat? (Un)Willingness and intentions to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 95, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumer perception and behaviour regarding sustainable protein consumption: A systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 61, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.A. The significance of sensory appeal for reduced meat consumption. Appetite 2014, 81, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, Y.; Uzundumlu, A.S.; Baran, D. How sensory and hedonic quality attributes affect fresh red meat consumption decision of Turkish consumers? Ital. J. Food Sci. 2015, 27, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akwetey, W.Y.; Ellis, W.O.; Oduro, I.N. Using whole cowpea flour (WCPF) in frankfurter-type sausages. J. Anim. Prod. Adv. 2012, 2, 450–455. [Google Scholar]

- Zayas, J.; Lin, C. Effect of the Pretreatment of Corn Germ Protein on the Quality Characteristics of Frankfurters. J. Food Sci. 1989, 54, 1452–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgar, M.A.; Fazilah, A.; Huda, N.; Bhat, R.; Karim, A.A. Nonmeat protein alternatives as meat extenders and meat analogs. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety 2010, 9, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osen, R.; Toelstede, S.; Wild, F.; Eisner, P.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U. High moisture extrusion cooking of pea protein isolates: Raw material characteristics, extruder responses, and texture properties. J. Food Eng. 2014, 127, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baune, V.M.C.; Baron, M.; Profeta, A.; Smetana, S.; Rohstoffes, B. Einfluss texturierter Pflanzenproteine auf Rohmassen hybrider Chicken Nuggets. Fleischwirtschaft 2020, 82–88. Available online: https://www.genios.de/fachzeitschriften/artikel/FLW/20200715/einfluss-texturierter-pflanzenprote/20200715540766.html (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J.W.; Key, T.J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R.T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Jebb, S.A. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 2018, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McAuliffe, G. A thematic review of life cycle assessment (LCA) applied to pig production. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 56, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; van Ierland, E.C. Protein Chains and Environmental Pressures: A Comparison of Pork and Novel Protein Foods. Environ. Sci. 2004, 1, 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, A. The Impact of Health Claims in Different Product Categories. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdiarmid, J.I.; Douglas, F.; Campbell, J. Eating like there’s no tomorrow: Public awareness of the environmental impact of food and reluctance to eat less meat as part of a sustainable diet. Appetite 2016, 96, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, C.; McLeay, F. Should we stop meating like this? Reducing meat consumption through substitution. Food Policy 2016, 65, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Impact of sustainability perception on consumption of organic meat and meat substitutes. Appetite 2019, 132, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullee, A.; Vermeire, L.; Vanaelst, B.; Mullie, P.; Deriemaeker, P.; Leenaert, T.; De Henauw, S.; Dunne, A.; Gunter, M.J.; Clarys, P.; et al. Vegetarianism and meat consumption: A comparison of attitudes and beliefs between vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and omnivorous subjects in Belgium. Appetite 2017, 114, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer, C.J.; Hudders, L. Meat morals: Relationship between meat consumption consumer attitudes towards human and animal welfare and moral behavior. Meat Sci. 2015, 99, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, A.M.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C. Major dietary protein sources and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Circulation 2010, 122, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sinha, R.; Cross, A.J.; Graubard, B.I.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Schatzkin, A. Meat intake and mortality: A prospective study of over half a million people. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.B. Plant-based foods and prevention of cardiovascular disease: An overview. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chalvon-Demersay, T.; Azzout-Marniche, D.; Arfsten, J.; Egli, L.; Gaudichon, C.; Karagounis, L.G.; Tomé, D. A systematic review of the effects of plant compared with animal protein sources on features of metabolic syndrome1-3. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, V.R.; Pellett, P.L. Plant proteins in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 59, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Profiling consumers who are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute in a Western society. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarup, S.; Christensen, T.; Denver, S. Are Organic Consumers Healthier than Others? In Proceedings of the 16th IFOAM Organic World Congress, Modena, Italy, 16–20 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capiola, A.; Raudenbush, B. The Effects of Food Neophobia and Food Neophilia on Diet and Metabolic Processing. Food Nutr. Sci. 2012, 03, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Damsbo-Svendsen, M.; Frøst, M.B.; Olsen, A. A review of instruments developed to measure food neophobia. Appetite 2017, 113, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falciglia, G.A.; Couch, S.C.; Gribble, L.S.; Pabst, S.M.; Frank, R. Food neophobia in childhood affects dietary variety. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000, 100, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, A.S.; King, S.C.; Meiselman, H.L. Consumer segmentation based on food neophobia and its application to product development. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaapila, A.; Tuorila, H.; Silventoinen, K.; Keskitalo, K.; Kallela, M.; Wessman, M.; Peltonen, L.; Cherkas, L.F.; Spector, T.D.; Perola, M. Food neophobia shows heritable variation in humans. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 91, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidigal, M.C.; Minim, V.P.; Simiqueli, A.A.; Souza, P.H.; Balbino, D.F.; Minim, L.A. Food technology neophobia and consumer attitudes toward foods produced by new and conventional technologies: A case study in Brazil. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoek, A.C.; Luning, P.A.; Weijzen, P.; Engels, W.; Kok, F.J.; de Graaf, C. Replacement of meat by meat substitutes. A survey on person- and product-related factors in consumer acceptance. Appetite 2011, 56, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Shi, J.; Giusto, A.; Siegrist, M. The psychology of eating insects: A cross-cultural comparison between Germany and China. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 44, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, M. The Culture of Food (La Fame e L’abbondanza. Storia Dell’alimentazione in Europa); Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Biesbroek, S.; Bas Bueno-De-Mesquita, H.; Peeters, P.H.; Monique Verschuren, W.M.; Van Der Schouw, Y.T.; Kramer, G.F.; Tyszler, M.; Temme, E.H. Reducing our environmental footprint and improving our health: Greenhouse gas emission and land use of usual diet and mortality in EPIC-NL: A prospective cohort study. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2014, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Croissant, Y. mlogit: Multinomial Logit Models. R Package Version 0.4-2. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mlogit (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Lüdecke, D. sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science. R Package Version 2.8.4. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjPlot (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Statista. Germany: Organic Food Purchase. 2019. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1085285/organic-food-purchase-in-germany/ (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Wansink, B. Changing Eating Habits on the Home Front: Lost Lessons from World War II Research. J. Public Policy Mark. 2002, 21, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Situating moral disengagement: Motivated reasoning in meat consumption and substitution. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 90, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzerman, J.E.; van Boekel, M.A.; Luning, P.A. Exploring meat substitutes: Consumer experiences and contextual factors. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Sonesson, U.; Baumgartner, D.U.; Nemecek, T. Environmental impact of four meals with different protein sources: Case studies in Spain and Sweden. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1874–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiking, H.; de Boer, J. Background, Aims and Scope. In Sustainable Protein Production and Consumption: Pigs or Peas? Aiking, H., de Boer, J., Vereijken, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, M.J.; Rae, A.N.; Vereijken, J.M.; Meuwissen, M.P.; Fischer, A.R.; van Boekel, M.A.; Rutherfurd, S.M.; Gruppen, H.; Moughan, P.J.; Hendriks, W.H. The future supply of animal-derived protein for human consumption. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, 2nd ed.; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Location | % |

|---|---|

| retailer | 48.6 |

| discount | 38.6 |

| butcher | 10.2 |

| market | 1.2 |

| online | 0.6 |

| others | 0.6 |

| farm | 0.2 |

| % | |

|---|---|

| never | 15.4 |

| sometimes | 62.2 |

| often | 18.2 |

| always | 4.2 |

| Statement | std. α | σ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I love meals with meat. | 0.84 | 3.94 | 1.00 |

| To eat meat is one of the good pleasures in life. | 0.85 | 3.38 | 1.08 |

| I’m a big fan of meat. | 0.84 | 3.58 | 1.07 |

| A good steak is without comparison. | 0.84 | 3.76 | 1.12 |

| By eating meat I’m reminded of the death and suffering of animals. (r) | 0.86 | 3.50 | 1.19 |

| To eat meat is disrespectful towards life and the environment. (r) | 0.86 | 3.30 | 1.19 |

| Meat reminds me of diseases. (r) | 0.86 | 3.86 | 1.18 |

| To eat meat is an unquestionable right of every person. | 0.86 | 3.57 | 1.12 |

| According to our position in the food chain, we have the right to eat meat. | 0.86 | 3.68 | 1.13 |

| Eating meat is a natural and indisputable practice. | 0.85 | 3.75 | 0.98 |

| I don’t picture myself without eating meat regularly. | 0.85 | 3.56 | 1.14 |

| If I couldn’t eat meat I would feel weak. | 0.85 | 3.12 | 1.19 |

| I would feel fine with a meatless diet. (r) | 3.32 | 1.14 | |

| If I was forced to stop eating meat, I would feel sad. | 0.85 | 3.38 | 1.15 |

| Meat is irreplaceable in my diet. | 0.84 | 3.43 | 1.11 |

| Statement | std. α | σ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I am constantly sampling new and different food. (r) | 0.74 | 2.75 | 1.17 |

| I do not trust new (different or innovative) food. | 2.93 | 1.11 | |

| If I don’t know what a food is, I won’t try it. | 3.85 | 1.00 | |

| I prefer food from different cultures. (r) | 0.72 | 2.59 | 1.07 |

| I am reluctant to eat foreign food that I see for the first time. | 0.74 | 2.96 | 1.21 |

| If I go to a buffet, meetings or parties, I’ll eat new food. (r) | 0.73 | 2.32 | 1.09 |

| I’m afraid to eat food that I did not eat before. | 0.73 | 2.49 | 1.23 |

| I am very particular about the food I eat. | 3.06 | 1.13 | |

| I will eat almost anything. (r) | 0.76 | 2.32 | 1.10 |

| I like to try new ethnic restaurants. (r) | 0.70 | 2.36 | 1.10 |

| Substitution of Meat | ||

| yes | no | |

| 54.2% | 45.8% | |

| Ranking list | ||

| nr | product | % |

| 1 | Fish | 48.3 |

| 2 | Cheese | 47.6 |

| 3 | Egg(s) | 41.7 |

| 4 | Pasta | 39.5 |

| 5 | Salad | 35.4 |

| 6 | Other legumes | 15.1 |

| 7 | Lentils | 9.6 |

| 8 | Nuts | 8.9 |

| 9 | Tofu | 6.3 |

| 10 | Seitan | 1.8 |

| 11 | Other | 1.1 |

| 12 | Tempeh | 0.4 |

| % | |

|---|---|

| never | 45.6 |

| tried it once | 16.0 |

| rarely | 20.0 |

| sometimes | 14.4 |

| frequently | 4.0 |

| Meat | Neither/Nor | Hybrid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| healthier | 31.0% | 27.2% | 41.8% |

| tastier | 62.4% | 20.8% | 16.8% |

| better for environment | 15.8% | 31.0% | 53.2% |

| better for animal welfare | 15.6% | 26.8% | 57.6% |

| I would choose … | 59.4% | 13.2% | 27.4% |

| Hybrid | Neiter/Nor | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| buy. freq. organic/free range | −0.038 | −0.328 |

| (0.141) | (0.166) | |

| healthier | 1.386 | 0.533 |

| (0.213) | (0.210) | |

| more tasty | 1.289 | 1.211 |

| (0.205) | (0.201) | |

| better for environment | 0.700 | 0.102 |

| (0.223) | (0.225) | |

| better for animal welfare | 0.498 | −0.430 |

| (0.250) | (0.224) | |

| Food Neophobia Scale (FNS) | −0.254 | −0.169 |

| (0.149) | (0.169) | |

| Meat Attachement (MAQ) | −0.837 | −0.241 |

| (0.168) | (0.171) | |

| buy. freq. plant-based alt. | 0.292 | −0.062 |

| (0.142) | (0.170) | |

| Constant | −1.470 | −0.950 |

| (0.234) | (0.171) | |

| Akaike Inf. Crit. | 710.008 | 710.008 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Profeta, A.; Baune, M.-C.; Smetana, S.; Bornkessel, S.; Broucke, K.; Van Royen, G.; Enneking, U.; Weiss, J.; Heinz, V.; Hieke, S.; et al. Preferences of German Consumers for Meat Products Blended with Plant-Based Proteins. Sustainability 2021, 13, 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020650

Profeta A, Baune M-C, Smetana S, Bornkessel S, Broucke K, Van Royen G, Enneking U, Weiss J, Heinz V, Hieke S, et al. Preferences of German Consumers for Meat Products Blended with Plant-Based Proteins. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020650

Chicago/Turabian StyleProfeta, Adriano, Marie-Christin Baune, Sergiy Smetana, Sabine Bornkessel, Keshia Broucke, Geert Van Royen, Ulrich Enneking, Jochen Weiss, Volker Heinz, Sopie Hieke, and et al. 2021. "Preferences of German Consumers for Meat Products Blended with Plant-Based Proteins" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020650

APA StyleProfeta, A., Baune, M.-C., Smetana, S., Bornkessel, S., Broucke, K., Van Royen, G., Enneking, U., Weiss, J., Heinz, V., Hieke, S., & Terjung, N. (2021). Preferences of German Consumers for Meat Products Blended with Plant-Based Proteins. Sustainability, 13(2), 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020650