Abstract

To successfully reduce their climate impacts, cities need a clear strategical path to decrease their energy consumption and increase their use of renewable energy. Consequently, local energy plans have recently become popular, notably in western Switzerland. These plans propose different pathways towards the achievement of economic, social, and environmental energy objectives, often supported by an action plan describing the possible projects and policies necessary to enact these pathways. However, the implementations of these local energy plans show a strong variability in efficiency and effectiveness. In this study, we survey the state of the implementation of local energy plans in 57 municipalities in western Switzerland. Based on this survey, we make four concrete propositions to reduce the difficulties faced by cities during the implementation of local energy plans and we test these propositions in three partner cities. These new tools, which aim at reinforcing municipal energy policy, can now be reused by local administrations in the study area and beyond.

1. Introduction

According to the United Nations Program for Human Settlements, cities consume between 60% and 80% of the energy produced worldwide and emit about 70% of total CO emissions [1]. Hence, energy management in cities will be critical to reach climate and energy targets in Europe and in the World. As a result, urban energy policy and planning has gained importance in recent decades in research and practice [2]. The city is now seen as the appropriate scale to enact efficient energy policies [3], as it has both the ability to coordinate individual actions, and better possibilities to adapt to local circumstances than national policy.

Following [4], urban energy policy can be defined as the activities undertaken by municipal authorities to influence the supply and demand of energy within their urban area and to manage the impacts of this consumption, especially on the environment. An efficient urban energy policy is generally supported by a local energy plan, which has the objective to efficiently manage energy resources and needs according to social, economic, and environmental goals. The appropriate content of local energy plans, and the process needed to draft and ratify them, is the subject of intense research, for example on the importance of participatory approaches [5], on the format of the energy objective used to drive the local energy plans [6], or on the possibilities of cities to act in the complicated field of energy [7]. Different reviews on urban energy planning methodologies [8,9,10,11] and on the simulation tools used to support these processes [12] are available and detail the current scope of local energy plans.

Since the debate over the contents of the most appropriate energy plans is still open, we will use the term “local energy plans” rather generally in this article, considering that many different formats of local energy planning are used in practice [8], such as the Sustainable Energy Action Plan (SEAP) based on the Covenant of Mayors [13], the municipal energy plans in Sweden [14], or territorial energy planning (PET from French) in western Switzerland. Even if we aim to encompass different types of local energy plans in this article, our results will be generally based on cities which use PET as their local energy plan.

Indeed, our study area is the Vaud Canton in Switzerland where PET is the most popular form of local energy plan and is also promoted by the cantonal authorities. PET plans are generally composed of [15]:

- A geo-referenced evaluation of the current local energy needs centred on building heating needs and electricity needs (present and future).

- A quantitative analysis of the different energy resources available to the community.

- Two to three scenarios aiming at reducing energy consumption while increasing the share of renewable resources based on the objectives selected by the city political authorities.

Maps and geo-referenced information are an important part of PET compared to other types of local energy plans (hence the term “territorial”).

If the format of PET is well-known locally and is generally accepted by the municipalities, the resources (human or financial) and the organisation necessary to implement these plans is often not well-defined. At European level also, methodologies to support the implementation of local energy plans are often lacking. Studies in this domain are relatively rare and are often limited to particular aspects of the implementation of energy plans. For example, a recent study in Denmark discussed the possible mismatches between the available modelling tools used to support energy planning and the needs of municipal administrations [16]. Another analysis has shown the constraints of using mapping tools to support the implementation of local energy plans [17]. The importance of an efficient monitoring system in this process has also been highlighted [18] as well as the impacts of national policy [19]. Moreover, detailed analysis of the interactions between a particular energy project and energy plans have expressed the importance of stakeholder involvement to enliven energy planning at a local level [20], confirmed by larger studies [21] and studies focused on particular stakeholder types [22,23]. Lists of recent projects and best practices are also available [24]. As a summary, even if the importance of implementation for efficient energy planning is often emphasised [10], general studies on the state of implementation of local energy plans and tools to improve it are necessary to accelerate the energy transition at municipal level.

Therefore, the goal of this study is better understand the state of the implementation of local energy plans and to improve it by:

- 1.

- Providing quantitative information about the state of the implementation of local energy plans in western Switzerland and the challenges related to this implementation process.

- 2.

- Developing four new tools which can be used by cities in Europe and in Switzerland to facilitate the implementation of local energy plans based on the identified challenges.

The paper will be structured as follows: we first describe our methodology, especially the one used to survey local energy plans. Then, we present the study area and the main partner cities for the study. The results of the survey are presented next. Based on these results, we introduce our considerations on the possible improvements to the current implementation practices. Finally, we present the new tools which are based on these considerations and on practical tests in the partner cities.

2. Methodology

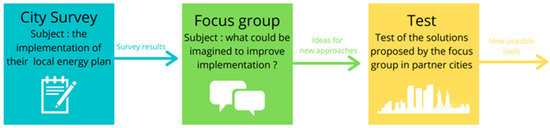

The methodology used in this study is composed of the following three main steps (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of the proposed methodology.

- 1.

- Collect experiences about the implementation of local energy plans in different municipalities through an online survey.

- 2.

- Analyse the answers to the survey in a focus group composed of energy experts and city administration in order to identify possible approaches to improve the implementation of local energy plans.

- 3.

- Test and improve these approaches in collaboration with three partner cities.

The main output of this process is the creation of four tools which can be reused by local administrations during the preparation and the implementation of their local energy plans to reinforce their local energy policy.

2.1. Survey Methodology

The survey was conducted online using the SurveyMonkey tool [25] during the month of June 2018. All the 91 contacted municipalities are situated in the Vaud Canton in western Switzerland (Figure 3) and are considered a regional centre by the cantonal authority in charge of energy. Identical questions were asked to all city administrations in French. When a contact was available, the survey was sent to the person in charge of energy. Otherwise, the city email address for general technical enquiries was used. The goal of this survey is to analyse the obstacles faced by local administrations when implementing their local energy plan. The survey has three sub-goals:

- Check the current state of local energy planning in different cities.

- Identify measures implemented as a result of local energy plans and evaluate the level of difficulty associated with each measure.

- Analyse the sources of these difficulties in terms of the availability of public policy resources such as judicial, human or financial resources, and in terms of the diversity of the policy instruments used.

A total of 91 municipalities were contacted and 57 answered, reaching a response rate of 63%. Large municipalities (above 15,000 inhabitants) have a higher response rate (88%) than smaller municipalities (33% for cities between 5000 and 10,000 inhabitants, 25% for cities between 2500 and 1000 inhabitants, and 5% for cities under 1000 inhabitants).

The selection of municipalities was not based on the existence of a local energy plan, as this survey was part of a larger study on PET. Hence, part of the answers comes from cities without a local energy plan available. Indeed, 50% of the answers to the survey originate from cities without a formal energy plan, 25% are currently writing a local energy plan and 25% are implementing their existing energy plan.

2.2. Analysis of the Survey’s Results

First, the survey results were analysed internally to identify critical concerns from the survey participants. Then, a focus group was formed to investigate these results in more depth. This group consists of the following members, selected because of their expertise in the field of energy management at the municipal level:

- The local officers in charge of energy in the three partner cities (Section 3).

- The person responsible for local energy plans at the cantonal level (Canton de Vaud).

- A consultant in charge of drafting different local energy plans in the region.

The purpose of this focus group is to reflect on the answers to the survey and to select the next steps for this study, notably identifying areas where an improvement in the implementation of PET is possible. The discussions of the focus group were deliberately centered on possible improvements. Hence, we did not conduct in-depth discussions on all challenges identified by the participants to the survey, but we focused the discussions on increasing stakeholders’ involvement inside and outside of the city administration, since the preliminary analysis of the survey results and existing literature [21] showed that it is a weak but critical point to successfully implement a PET.

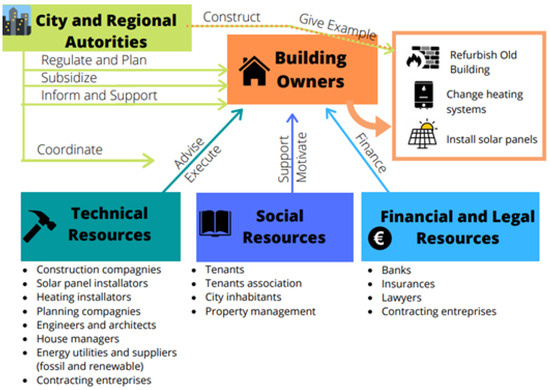

Practically, the focus group met three times between February and May 2019. The two first meetings were composed of a presentation of the survey results followed by a group discussion whose main outcomes are presented in Section 5. The final meeting was a workshop focused on the needs of the intermediary actors listed in Figure 2. The workflow for this last meeting is available in the Supplementary Materials (in French).

Figure 2.

Relationships between buildings owners, intermediary actors, and city authorities—based on the focus group discussion.

2.3. Development and Test of New Tools in Partner Cities

Our final step is to transform the approaches identified by the focus group into practical tools in collaboration with three partner cities. This process was adapted for each city. Section 6 describes which tools (see the same section for tool definition) were co-created with which municipalities. To avoid unnecessary length to the article, the different improvements proposed by each city administration will not be listed in detail, but their feedback has generally been central to this research. Indeed, the development of the different tools was supported by the the city energy officers who were part of the focus group. Then, practical tests of these new tools were implemented. Finally, feedback was collected and the tools were improved based on the collected experiences.

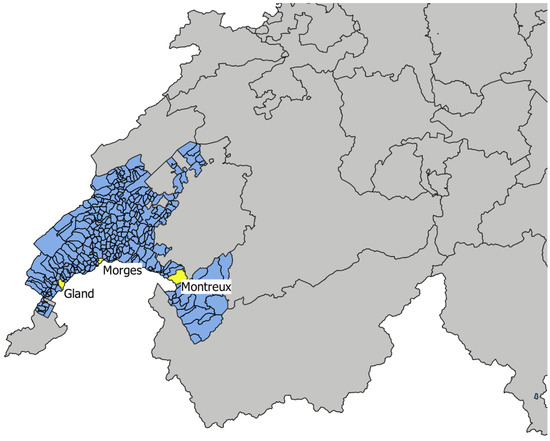

3. Partner Cities

We briefly present below the three partner cities with which the different tools were developed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Position of the partner cities in western Switzerland.

3.1. Montreux

Montreux is a city of about 25,000 inhabitants on the shore of the Geneva Lake in the Vaud canton in Switzerland. It signed the Covenant of Mayors and has been certified for its energy policy by the European energy program “Cité de l’énergie” since 1999. It reached the gold level in this program in 2016. The involvement of the city of Montreux is centred on an in-depth analysis of building owners to support the ongoing communication process with these owners.

3.2. Morges

Morges is a city of about 15,000 inhabitants, situated close to the Geneva Lake between Lausanne and Geneva. In accordance with the Swiss energy strategy 2050 [26], the city of Morges has defined the following objectives in its energy strategy for 2035 (compared to the situation in 2017):

- A 43% reduction in the final energy consumed per inhabitant.

- A 13% reduction in the electricity consumed per inhabitant.

- A 41% reduction in CO emission per inhabitant.

It is currently preparing a local energy plan to analyse which actions are necessary to achieve these objectives. Our partnership in this project is focused on the selection of different measures in cooperation with municipal authorities and on the communication of the objectives of the energy strategy in a relevant way for the different stakeholders. Characterisation of different building owners is also of interest for the city of Morges.

3.3. Gland

Gland is also situated close to the Geneva Lake, but closer to the city of Geneva than the two other partner cities. It has about 13,000 inhabitants. Before this project, the city of Gland began to update its energy plan. In this project, the city is especially interested in specifying its updated objectives, analysing which measures would be necessary to reach these different objectives, and supporting an efficient cooperation between the different actors in the local government.

4. Survey Result

In this section, the main results of the survey for the 15 cities which are currently implementing a local energy plan are presented. The complete survey contains 35 questions, but part of these questions concerns subjects which are only locally relevant such as the knowledge of available resources to support PET. Hence, we focus here on six questions of larger interest. The list of questions and the format of the questionnaire are available in the Supplementary Materials (in French).

4.1. Actions Taken and Policy Instrument Used

The first survey question is about which type of actions the cities have implemented as a result of their local energy plan. According to the survey results, 14 out of 15 cities with a local energy plan have taken measures as a result of this plan. To obtain a general picture among the very different actions taken, we separated this interrogation into two parts:

- 1.

- In which domain (building, mobility, etc.) are the actions taken?

- 2.

- Which type of policy instrument (subsidies, communication, etc.) is used?

For both questions, default options were given in the survey, but it was possible to add supplemental fields when needed.

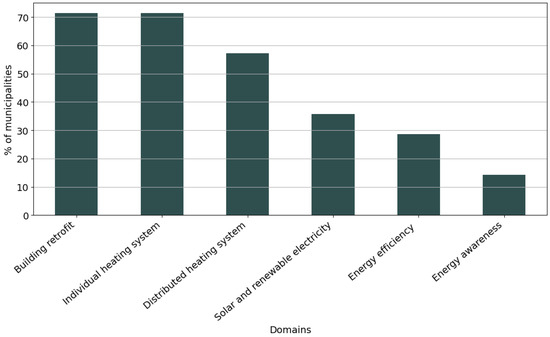

4.1.1. Actions Effectively Implemented

As the result of their local energy plans, most cities have taken actions focused on buildings and heating needs (Figure 4). Indeed, measures towards increasing building refurbishment and renewable heating systems are taken by more than 70% of the fourteen municipalities which answered this question positively. This is consistent with the 2050 Swiss Energy Strategy [26] which has strong objectives of decreasing heat consumption and increasing the renewable energy used for heating and cooling. This is also consistent with the form of local energy plans in the studied area, which has a strong focus on building heating needs.

Figure 4.

Domains in which the cities have implemented measures as the result of the local energy plan.

Actions to support an increase in local electricity production are also taken, especially towards the supporting of solar energy (36% of municipalities). Actions to increase public awareness and support of efficiency-related issues (mostly for industrial actors) have been taken by less than a third of the municipalities. The low percentage of municipalities acting on energy awareness must however be put into perspective: it was implied in the survey that the usage of communication as a policy instrument to reach particular objectives in other domains was not an action linked to the "energy awareness" domain (Figure 5).

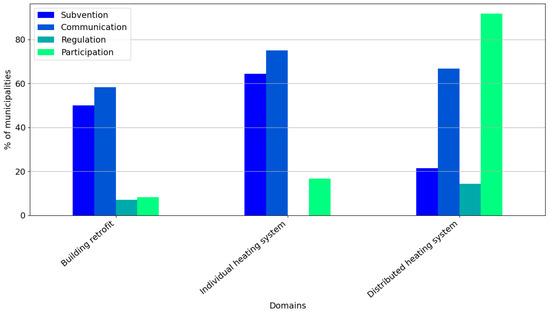

Figure 5.

Type of policy instruments used by the surveyed municipalities for the three domains.

4.1.2. Types of Policy Instruments Used

For the domains where more than 50% of the surveyed administration had taken actions, we analysed the type of policy instruments used. The type of policy instruments considered in this study are subsidies, information, regulations, and participation (all types of participation from a simple consultation to deeper negotiations are included). Among these types of policy instruments, subsidies and communication are often used by cities in fields where individual building owners are concerned such as building retrofitting and individual heating systems (Figure 5). For district heating networks, which are larger infrastructure projects with different investors, participation (which includes negotiation) is more often used. Based on our results, regulation is not often used at city level, probably due to the lack of institutional competence at this governmental level.

4.2. Identified Difficulties and Lack of Resources

The next question is about the challenges encountered by the municipalities during the implementation of local energy plans. This question is also separated into two parts: first, we asked how difficult it is to implement measures in different domains. For this question, the domains often selected in Figure 4 are completed by particular measures often implemented at local level, the creation of a local subsidy plan (43% of municipalities) and the direct retrofitting of city buildings (71%). Secondly, we asked about the type of difficulty encountered.

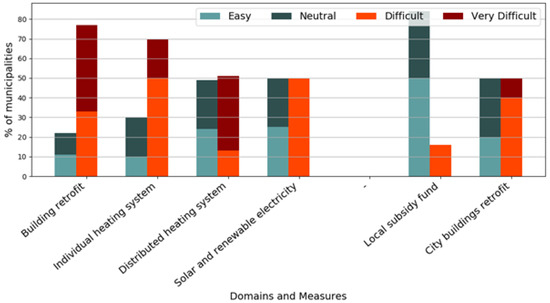

Two domains were judged as especially difficult by the survey participants: Building retrofitting and individual heating systems (Figure 6). The supply of renewable electricity was judged as relatively easy on average, probably because the development of certificates of origin and the decrease in the price of solar panels support the creation of efficient measures in this domain (even if the actual efficiency of the electricity certificate in decarbonising the energy systems can be debated [27]). The development of district heating networks (DHN) was judged as more difficult than the supply of renewable electricity but easier than building retrofitting.

Figure 6.

Perceived implementation difficulties in different domains of local energy plans (left side of the Figure) and perceived difficulties in implementing particular measures (right side of the Figure).

The perceived reasons for these difficulties are multiple (Table 1). Nevertheless, the lack of the actor’s involvement and the lack of financial resources are the most often cited difficulties. The lack of the actor’s involvement is stronger in domains of actions which are judged as particularly difficult (building retrofitting and individual heating systems). These domains are also those for which the cities indicated a low usage of participatory approaches (Figure 5). For the development of district heating networks, where participation is more often used, stakeholders involvement is less of a problem based on the survey results (Table 1). Indeed, the successful installation of a DHN is often the result of a public–private partnership and required an active cooperation of large building owners as future key customers. Hence, the advantages of participatory approaches are more obvious to the different stakeholders in this latter case.

Table 1.

The percentage of municipalities which identified a lack in a resource for the different domains of actions. Value above 50% are marked in bold and average value above 35% are marked in orange. Only the municipalities which chose a domain of action as “difficult” or “very difficult” were invited to answer here.

5. Outputs from the Focus Group

While it would be too long to relate precisely the different discussions of the focus group, we summarise and organise the main results of the discussions in this section.

5.1. Importance of Stakeholder Involvement

Based on the survey results, the lack of actors’ involvement and of financial resources are the most problematic obstacles when implementing a local energy plan. While the focus group strongly agrees that financial resources are key to a successful implementation of a PET, it does not seem to be a subject on which progress can be made inside focus group. Moreover, local funding sources for energy plans are available in the study area, notably the possibility of creating a city-wide tax on electricity and regional subsidies.

Hence, most discussions were centred on stakeholders’ involvement. Indeed, the focus group noticed that this issue is central for city energy policy because (a) the city has little direct impact on many of the specific energy-related objectives, meaning that the city cannot directly put them in movement, (b) there are little options for regulation in the current legal system. For example, increasing building refurbishment is a usual specific objective to answer the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but the city cannot directly refurbish buildings which are its property and there is currently not a lot of regulations to force owners to refurbish a building. Indeed, since laws related to buildings are under the responsibility of cantonal authorities [28], the city has only limited possibilities to regulate refurbishment directly and must find resource to increase refurbishment on a voluntary basis. It is interesting to note that the lack of legal resources is considered as a difficulty by the interviewees (Table 1), but less often that other type of difficulties even if it seems critical from an outsider’s point of view.

An active participation, and by extension, acceptance of local actors of the city energy policy is therefore necessary to implement it. However, the responses to the survey (Figure 5) show that municipalities do not often use participation as a leverage in most of their local energy plans (except for DHN planning and construction). A correlation is also observed between the perceived difficulties of implementing measures in different energy domains and the usage of participation as a policy instrument. For example, DHN is the domain for which participation is the most often used, as well as the domain for which the issues related to actors’ involvement is perceived as the lowest (Figure 5 and Table 1). Hence, efficient tools to increase actor participation in local energy plans could be useful to simplify their implementation.

5.2. Importance of Building Owners in Local Energy Plans

Then, the focus group noticed the key role of building owners for the domains which are often selected as critical domains for local energy plans (see Figure 4 for a list of these domains). Indeed, building owners take the final decision on building refurbishment, heating systems, installation of solar panels, and connection to a DHN. The construction of a DHN is nevertheless decided by the cities’ government or/and a local utility.

It is possible that this key role of building owners is stronger in the Vaud Canton than in other parts of Europe because of the focus on building consumption in PET-type local energy plans. Mobility for example is not an important part of the PET process. Nevertheless, heating, cooling, and decentralised solar energy production are central to local energy plans in general. Hence, increasing the participation of local building owners in local energy plans is central to reach the expected results.

5.3. How to Increase Participation of Building Owners?

As previously said, building owners are key actors in PET, but they are not strongly empowered, i.e., they often lack the financial, technical, and legal resources to make optimal energy-related decisions. Indeed, they are not professional in energy and are prey to misconceived opinions on renewable energy solutions. For example, the average building owner might not know the advantages or disadvantages of heat pumps versus gas boilers and would rely on experts to select a solution. Moreover, the high investment cost needed for energy refurbishment and renewable energy production implies an important role for banks and financial actors as a source of capital. Hence, a strong involvement of intermediary actors in the building owners decisions is expected in energy-related decisions.

As a consequence, a first identified possibility to indirectly increase participation of building owners in PET is to increase support for the intermediary actors in these plans. A large reflection of the focus group was about identifying these intermediary actors (building companies, banks, heating installers, architects, etc.) and their needs. Figure 2 is a summary of this reflection. Coordination between these intermediary actors by the city administration is a relatively low-cost measure, which could have positive impacts on the implementation of local energy plans.

A second possibility to increase participation of building owners in local energy plans is to better understand what type of building owners are present in the territory to adapt local measures to their constraints. Indeed, building owners’ constraints strongly differ between owner types. A life insurance firm which owns rented buildings does not have the same possibilities and limitations as a small property owner whose conditions are also different to a group of condominium owners. Nevertheless, there are indications that two small property owners often have relatively similar needs as shown, for example, through semi-structured interviews with local building owners (conducted in the city of Gland in December 2020). Even if this fact is true it is necessary to identify the type of building owners (rented/not rented building, private/public/physic owners, individual/group ownership) to start an efficient communication plan. Moreover, identifying large owners in terms of energy use, available wall and roof areas is also indispensable to optimise implementation. However, easy-to-use tools for creation of a building owner typology are currently missing. Should information be available, cities could develop efficient approaches to involve each type of owner separately.

5.4. Empower Decision Makers

In a second step, the focus group centred its discussions on decision makers at the city level and their involvement in local energy planning. Local officials in charge of energy are of course strongly involved in local energy planning. Nevertheless, the efficiency of their involvement is critical and may vary.

One identified challenge is that the degree of technical complexity in energy issues is high. Consequently, local energy plans are often prepared by consultants, with the support of the city administration. The plan is then commented and voted on by local authorities, which therefore only have limited participation in the drafting of this plan. This does not help future implementation.

However, it is difficult to imagine that city officials would have the time and the necessary competences to participate in each step of the creation process of a local energy plan. As a consequence, it is expected that external consultants are part of the process. In a sense, this is a version of the well-known principal-agent problem [29] (i.e., a mismatch in priorities between an actor and the representative authorised to act on their behalf).

To reduce this problem, a possible improvement is to create an option for city officials to give indications on the type of actions expected at the start of the creation process of a local energy plan. Indeed, feedback and comments from city officials are often requested only at the end of the process when modifications are complicated. Options for a more active participation since the beginning of the process, beyond the mere statement of political goals, would be needed.

5.5. The Need for Clear Objectives

Finally, the importance of separating actions and objectives was discussed. Indeed, quantitative objectives are set by cities in local energy planning in nearly all cases and about 70% of the cities surveyed have indicated that they have a system to follow these objectives. Nevertheless, each city and village has developed its own system and comparisons between cities are complicated. A common system would be useful. Information about baseline situations is especially needed. Currently, existing statistical information is often not used to understand the situation because of the lack of clear methods to this end, and because of the large uncertainties on the quality of some of the available data such as renovated buildings.

Moreover, because of the indirect nature of many energy-related measures that a city can implement, a separation should be made between general objectives, specific objectives, and indicators related to the different measures. In other words, one should separate large societal goals from what the administration can achieve. For example, if the city general objective is to decrease CO emission per inhabitant, a specific objective might be to increase the refurbishment rate to decrease fossil heating needs. Nevertheless, the city will not directly retrofit the buildings in its territory. A more probable course of action is a bundle of different measures such as subsidy for energy-efficient walls and windows, refurbishment from city-owned buildings, and awareness-raising campaigns targeting building owners. To set objectives clearly, these three levels (general, specific, and measure-related indicators) should be separated. Indicators should be set both on the macro level and to follow the measures taken by the administration. Methods to establish quantitative links between general objectives (e.g., decreasing CO of a certain amount per inhabitants) and specific objectives (e.g., an indicative number of buildings to renovate) are possible to develop and should be used. In the current situation, however, only qualitative links between measure-specific indicators (e.g., number of subsidies aimed to support windows substitution) and specific objectives (e.g., a number of buildings to renovate) seem possible.

6. Presentation of the Developed Tools

Four tools to support the implementation of local energy planning have been developed based on the different needs highlighted by the focus group. They have been integrated in the development and implementation process of local energy plans in the three partner cities. These partnerships have allowed us to specify the form of the different tools and to test their usefulness in realistic cases. While a detailed description of the inputs of each city would be beyond the scope of this article and complicated to document, Table 2 gives a summary of the involvement of each city and summarises the needs to which tools answer.

Table 2.

Involvement of the different cities in the tool development.

6.1. Tool 1: Identification of Owner Typology

The first tool is a mapping tool which indicates the typology of the different building owners. In addition to the evaluation of the building heating needs, the following characteristics of each building are determined:

- Is the building used as a habitation, an office space or another usage (including industry buildings)?

- Is the building rented or does the owner directly live or use the building?

- Is the building owned individually, as a condominium (each owner has one flat) or as a group (the group of owners has the joint control of the whole building)?

- Is the building owned by the government, a legal organisation or a physical person?

- What is the age of the owner(s)? (for physical person);

- Does the owner live in the region?

Most of these pieces of information can be obtained from the land register. The status “rented or not” can be inferred from a joint query between the land and census registers. The interest of this tool is in the linkage between the information related to energy and building refurbishment status with the information related to the building owners. The information is geo-referenced and presented in a format ready for use in a geographical information system. Strong standards in personal data protection are necessary for the creation and the management of these data.

In practice, the collection of information about building owners allows:

- Identification and contacting of the owners of large buildings which have a strong impact on energy-related objectives such as an increase in the refurbishment rate.

- Creation of subsidy and support programs which are in coherence with the type of owner of a territory, e.g., the number of condominiums can be shown in some territory as more important than previously thought, which supports the creation of programs directed at this type of owner, such as legal and mediation support for owner groups.

- Targeting of owners which are close to new infrastructures such as DHN.

- Evaluation of the success of energy programs for different types of building owner.

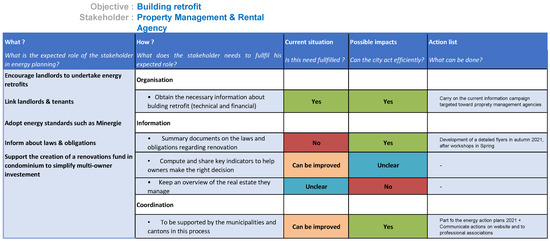

6.2. Tool 2: Checklist with Needs of Intermediary Actors

The second tool is a checklist, illustrated in Figure 7, which contains the needs of the intermediary actors as identified by the focus group (Figure 2). The concept of this tool is to use this checklist on an actual or proposed local energy plan. The needs of different intermediary actors are analysed separately in two phases: first, the user analyses if the need is fulfilled in the actual situation or not. Secondly, if the need is not fulfilled in the current situation, the user analyses if the municipality can improve the situation. In other words, is it possible to implement efficient measures to fulfil this need fully or partially?

Figure 7.

Tool 2: An extract from the checklist for the intermediary actor “property management and rental agencies”. Contains illustrative data. Translated from French.

This checklist should be used by people who have some knowledge of the region and are aware of the possibilities for actions in the city in the current situation. The analysis is qualitative, and its merit lies in opening discussion about potential energy-related measures which target intermediary actors often forgotten in local energy plans, such as local construction companies or financial institutions.

6.3. Tool 3: Early Workshop for Local Officials

An important need identified by the focus group is to efficiently involve decision makers at an early stage in the drafting process of local energy plans, when quantitative analysis of the city energy situation is not finished. To this end, we proposed and tested different workshops. The proposed final workshop is split into two parts:

In the first part, the local authorities, who are already informed about the principles of their future local energy plan, specify what their positions are on their preferred philosophy for their action plan. The following options are available:

- Visionary: a local energy plans centred on innovation and new technical solutions.

- Ambitious: going beyond national goals and putting the result of the local energy plan at the centre of the city management.

- Social: in addition to the environmental dimension, taking a particular interest in the social impacts.

- Equitable: giving particular importance to the fact that efforts should not be centred on a particular actor but shared among the inhabitants and enterprises of the city.

- Communicative: having a strong focus on communication actions to share objectives and actions with the population.

- City-centric: a local energy plan focused on actions inside the administration and on energy refurbishment in the buildings owned by the city.

- Cost-conscious: a local energy plan which is cost-conscious, and does not drain the city’s finances.

In a second part, the participants select their preferred policy instrument (regulation, subsidy, communication, etc.) for selected domains of action of local energy plans (refurbishment, local electricity production, renewable heating, etc.).

In both cases, the participants vote using stickers, after a short group discussion. Each participant has two votes available for each part. The workshop can be relatively short (about one hour), increasing chances of participation, while collecting valuable feed-backs for the administration and the consultant in charge of drafting the local energy plan.

6.4. Tool 4: Redefine Specific Objectives to Improve Their Comparability

The last proposed tool is relatively straightforward: it is a reformulation of the specific objectives of a local energy plan in terms of the effort needed to reach them.

For example, a specific objective to lower the city heating demand of 20% through building refurbishment in 2035 can be reformulated as an objective to renovate 26 multi-storey buildings and 32 single family homes each year. An objective to reach 32% of renewable energy can be reformulated in terms of the number of heating systems to be installed each year. Similarly, an objective on yearly solar electricity production can be presented as a surface of solar panels to be installed each year. More examples can be found in the flyer presenting the energy strategy of the partner city of Morges [30] and in Figure 8 adapted from the same document.

Figure 8.

Tool 4: An example of reformulation of a specific objective, adapted from the partner city of Morges [30]. It describes the objective of the city to produce 10 GWh of electricity each year locally which has been reformulated as covering a third of a football pitch with solar panels each year.

A quantitative definition of specific objectives is needed to use this tool as well as the data necessary to evaluate the current situation. The reformulation is generally less quantitative, as it often depends on the size of the different installations. Hence, this tool is not usable to entirely redefine the current objectives. Its goal is to illustrate specific objectives to better communicate them to the decision-makers and the population. It also allows the citizen to evaluate the effort needed to reach each objective as the reformulated objective is often easier to compare to the current situation than long-term energy-based objectives. As a consequence, a reformulation of specific objectives supports informed decisions from city authorities and helps to communicate objectives to the population, which helps with actors’ involvement and participation. For example, individual owners can feel empowered when knowing that their building is one of the 30 buildings that needs to be renovated every year. The numbers may seem more achievable and less abstract than a statistic giving a total surface to be renovated for the city.

Moreover, reformulated objectives are often easier to compare to collected data. For example, it might be easier to collect the number of building permits for renovation than to recalculate the renovation rate each year. Likewise, the surface of newly connected solar panels to the electricity network is often easier to obtain than the electricity produced by them, which might include auto-consumption. Hence, this tool also simplifies the monitoring process.

6.5. Communication and Further Documentation

These four tools are summarised in a “guide for municipalities to implement territorial energy plans” (in French), which is available in the Supplementary Materials. In this guide, we present the tools described here and information on how to draft an efficient action plan based on participatory approaches.

7. Conclusions

The goal of this study is to support the implementation of local energy plans in Switzerland through a stronger involvement of the different stakeholders. To this end, four new tools have been developed to improve the elaboration and the implementation of local energy plans in western Switzerland, based on a detailed survey and the inputs from the focus group.

These tools are not sufficient on their own to efficiently implement a new local energy planning. Indeed, the whole process is highly dependent on local conditions, such as the existing build environment, demographic changes, stakeholder interests, and local administrative capacities. Nevertheless, our hypothesis states that the proposed tools, which are easily re-usable and adaptable to local circumstances, can be helpful in practice and enrich the toolbox of municipalities and consultants tasked with the implementation of local energy plans. Moreover, even if our study is focused on the Vaud Canton in Switzerland, most of the tools can be adapted to different countries which might face similar challenges to the ones identified by the focus group.

In this study, we stressed the importance of testing processes used to develop and implement local energy plans. As we start to reach a critical number of municipalities having created and followed different local energy policies, it is important to evaluate these different energy strategies to understand what functions and what the current challenges are. This part is often under-studied even though it is a required step towards energy policies capable of answering current global environmental challenges such as climate change.

The use of these tools assures that the energy plan takes into account a broad panel of information, allowing the plan to be better received by local actors. The participatory processes which take place have the additional impact of raising awareness on the topic of energy with the included parties. Indeed, they do not only participate in the creation of the plan, but are also informed, and eventually more prone to accept responsibility thanks to their involvement.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su131910970/s1, Figure S1: Triangle des acteurs pour chaque action phare. Table S1: Ressources à disposition de l’administration pour «influencer» les acteurs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, v.G.D. and F.P.; Funding acquisition, F.P.; Investigation, v.G.D. and F.P.; Methodology, v.G.D., F.P., M.B. and D.C.; Writing—original draft, v.G.D.; Writing—review & editing, v.G.D., F.P., M.B. and D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Swiss Federal Office of Territorial Development and the Cantonal Directorate for Energy of the Vaud Canton through the Interreg VB409 project “IMEAS—Integrated and Multi-level Energy Models for the Alpine Space”, as well as the cities of Morges, Gland, and Montreux.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank Isabelle Godat-Maurice for her English proofreading and the different members of the focus group for their participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Programme, United Nations Human Settlements World Cities Report Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures; Technical Report; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016.

- Pasimeni, M.R.; Petrosillo, I.; Aretano, R.; Semeraro, T.; De Marco, A.; Zurlini, G. Scales, strategies and actions for effective energy planning: A review. Energy Policy 2014, 65, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajot, S.; Peter, M.; Bahu, J.M.; Guignet, F.; Koch, A.; Maréchal, F. Obstacles in energy planning at the urban scale. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 30, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keirstead, J.; Schulz, N.B. London and beyond: Taking a closer look at urban energy policy. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 4870–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivner, J.; Björklund, A.; Dreborg, K.; Johansson, J.; Viklund, P.; Wiklund, H. New tools in local energy planning: Experimenting with scenarios, public participation and environmental assessment. Local Environ. 2010, 15, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Neves, A.R.; Leal, V. Energy sustainability indicators for local energy planning: Review of current practices and derivation of a new framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2723–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, S. Capacity to Act: The Critical Determinant of Local Energy Planning and Program Implementation; Technical Report; Columbia University Center for Energy: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Yu, H.; Peng, Z.; Zhao, M. Methods and tools for community energy planning: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 1335–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.D.; Bansal, R.; Raturi, A. Multi-faceted energy planning: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 38, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirakyan, A.; De Guio, R. Integrated energy planning in cities and territories: A review of methods and tools. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 22, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charani Shandiz, S.; Rismanchi, B.; Foliente, G. Energy master planning for net-zero emission communities: State of the art and research challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137, 110600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, R.; Shikha, S.; Ravindranath, N. Decentralized energy planning; modeling and application—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinakis, V.; Doukas, H.; Xidonas, P.; Zopounidis, C. Multicriteria decision support in local energy planning: An evaluation of alternative scenarios for the Sustainable Energy Action Plan. Omega 2017, 69, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Mårtensson, A. Municipal energy-planning and development of local energy-systems. Appl. Energy 2003, 76, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide Pour une Planification Energétique Territoriale, Canton de Vaud, Département du Territoire et de L’environnement, Direction de l’énergie; Technical Report; Canton de Vaud: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2016. (In French)

- Ben Amer, S.; Gregg, J.S.; Sperling, K.; Drysdale, D. Too complicated and impractical? An exploratory study on the role of energy system models in municipal decision-making processes in Denmark. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 101673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Backhaus, N.; Buchecker, M. Mapping meaningful places: A tool for participatory siting of wind turbines in Switzerland? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delponte, I.; Pittaluga, I.; Schenone, C. Monitoring and evaluation of Sustainable Energy Action Plan: Practice and perspective. Energy Policy 2017, 100, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, M.; Pollitt, M.G.; Steer, S. Local energy policy and managing low carbon transition: The case of Leicester, UK. Energy Strategy Rev. 2015, 6, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen, N.; Caussarieu, M.; Petersen, U.R.; Karnøe, P. Energy plans in practice: The making of thermal energy storage in urban Denmark. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 79, 102178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, I.; Hoppe, T. Analysing the Institutional Setting of Local Renewable Energy Planning and Implementation in the EU: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunreiter, L.; Blumer, Y.B. Of sailors and divers: How researchers use energy scenarios. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 40, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, P.; Adler, C.; Patt, A. Do stakeholders’ perspectives on renewable energy infrastructure pose a risk to energy policy implementation? A case of a hydropower plant in Switzerland. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kona, A.; Melica, G.; Calvete, S.R.; Zancanella, P.; Iancu, A.; Gabrielaitiene, I.; Saheb, Y.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; Bertoldi, P. The Covenant of Mayors in Figures and Performance Indicators: 6-Years Assessment. Publ. Off. Eur. Union 2015, JRC92694, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- SurveyMonkey Inc. Available online: www.surveymonkey.com (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- SuisseEnergie. Feuille D’information Sur L’énergie no 5: Stratégie Energétique 2050; Technical Report; SuisseEnergie: Bern, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Darmani, A.; Rickne, A.; Hidalgo, A.; Arvidsson, N. When outcomes are the reflection of the analysis criteria: A review of the tradable green certificate assessments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constitution Suisse (Cst), art. 89, al. 4. 1999. Available online: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1999/404/fr (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Cvitanic, J.; Zhang, J. Contract Theory in Continuous-Time Models; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stratégie Energétique 2035—Ville de Morges. Ville de Morges. 2020. Available online: https://www.morges.ch/media/document/1/strategie_energetique_2035.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021). (In French).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).