Abstract

Mycological conservation has finally come of age. The increasingly recognized crucial role played by fungi in ecosystem functioning has spurred a wave of attention toward the status of fungal populations across the world. Milkcaps (Lactarius and Lactifluus) are a large and widespread group of ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes; besides their ecological relevance, many species of milkcaps are of socio-economic significance because of their edibility. We analysed the presence of milkcaps in fungal Red Lists worldwide, ending up with an impressive list of 265 species assessed in various threat categories. Lactarius species are disproportionally red-listed with respect to Lactifluus (241 versus 24 species). Two species of Lactarius (L. maruiaensis and L. ogasawarashimensis) are currently considered extinct, and four more are regionally extinct; furthermore, 37 species are critically endangered at least in part of their distribution range. Several problems with the red-listing of milkcaps have been identified in this study, which overall originate from a poor understanding of the assessed species. Wrong or outdated nomenclature has been applied in many instances, and European names have been largely used to indicate taxa occurring in North America and Asia, sometimes without any supporting evidence. Moreover, several rarely recorded and poorly known species, for which virtually no data exist, have been included in Red Lists in some instances. We stress the importance of a detailed study of the species of milkcaps earmarked for insertion in Red Lists, either at national or international level, in order to avoid diminishing the value of this important conservation tool.

1. Introduction

Milkcaps are mushroom-producing fungi within the basidiomycetous family Russulaceae. Traditionally comprised in the genus Lactarius, the group has undergone a deep taxonomic revision during the last decade or so. Studies based on multigene phylogenies have shown that Lactarius is not monophyletic, revealing the existence of two clades: the subgenera Piperites, Russularia, and Plinthogalus constituting the larger genus Lactarius sensu novo, and the subgenera Lactariopsis, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Russulopsis, Gerardii, and the former Lactarius sections Edules and Panuoidei making the newly erected genus Lactifluus [1,2,3,4,5].

Combined, Lactarius and Lactifluus form one of the most prominent groups of ectomycorrhizal (ECM) basidiomycetes [6,7,8]. With well over 650 species described worldwide, Lactarius + Lactifluus taxa play a key role as mycobionts of trees and shrubs in a vast range of ecosystems, from temperate Mediterranean-type vegetation to boreal coniferous forests, from rainforests of Southeast Asia to the Mesoamerican Neotropics, passing through tropical Africa with its miombo woodland and Eucalyptus and Nothofagus forests in Australia and New Zealand, respectively [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. In Europe, about 110 Lactarius species are recognized, and nine Lactifluus taxa [22,23,24]. While Lactarius occurs mostly in temperate regions, Lactifluus seems to have its center of diversification in tropical Africa, from where the largest number of species have been described, followed by tropical Asia and the Neotropical region [5,25].

Besides the importance of milkcaps in the health of forest ecosystems as ectomycorrhizal obligate symbionts, several species also have a considerable socio-economic value as appreciated edible mushrooms. Some 56 species have been reported as regularly collected and eaten in at least 17 countries (e.g., several European countries, Russia, China, Central and South America, Africa), although these figures are probably underestimated because little information is available for the local consumption of many African species [19,26]. Indeed, a very recent account of edible mushrooms species at the global scale lists some 100 edible milkcaps [27]. Lactarius deliciosus, commonly called saffron milkcap, is particularly popular, especially in Europe. It has been introduced with Pinus hosts in large areas outside its original range and is one of the few ectomycorrhizal mushrooms that has been successfully cultivated [28].

The significance of macrofungi conservation in virtue of their ecological role and their cultural and socio-economic importance, is increasingly appreciated. Although there is still a long way to go before these organisms receive the attention and protection they deserve, macrofungi are starting to be considered in several countries from Europe and other regions, and plans to protect and manage their diversity drafted (e.g., [29,30]). We focus on the conservation situation of milkcaps, particularly in European countries, discussing the status of those elements of knowledge on which any protection efforts must be based, i.e., taxonomy, ecology, and distribution.

2. Compilation of Data

2.1. Red Lists

Available fungal Red Lists—either officially adopted at national or international level or drafted but still considered ‘unofficial’—were browsed (see Supplementary Materials for details) and information regarding milkcaps extracted (see Table 1). Information on fungal Red Lists was retrieved from the dedicated pages of the European Council for the Conservation of Fungi (ECCF) website (http://www.eccf.eu/redlists-en.ehtml (accessed on 7 April 2021)) and the State of the World’s Fungi 2018 [31] (see https://stateoftheworldsfungi.org/, accessed on 12 April 2021), with a few updates and exceptions. Despite all efforts, we were not able to access the Red Lists of Belarus, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Moldova. On the other hand, several of the Red Lists we browsed contained no mention of milkcaps, and, thus, were not quoted. Relevant cases include Canada, Chile, Colombia, Italy, Latvia, Mexico, Russian Federation, United States, Uzbekistan. For each species, all occurrences in international and national Red Lists were reported, quoting the threat categories used in the original assessments. In the case of IUCN Red List categories, only categories (Critically Endangered, Endangered, etc.) were reported, excluding criteria (A to E), and subcriteria (1, 2, etc.; a, b, etc.; i, ii, etc.; for a complete description see [32]. This is because in most cases these further details are omitted in national Red Lists. In the case of the Global Fungal Red List Initiative (see below), we considered milkcap species at any stage of assessment, from simply ‘nominated’ or ‘proposed’, up to fully assessed and approved.

Table 1.

Species of milkcaps in national and international Red Lists.

2.2. Taxonomy and Nomenclature

Species were listed in Table 1 using the nomenclature adopted in the browsed Red Lists, noting divergence from current official nomenclature when appropriate. In case of invalidity and synonymy, reported in the notes, we followed (as for September 2021) Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org/ (accessed on 3 September 2021)), MycoBank (http://www.mycobank.org (accessed on 3 September 2021)), and Russulales News (https://www2.muse.it/russulales-news/in_characteristics.asp (accessed on 3 September 2021)). Moreover, we discussed the validity of specific taxa in light of the most recent phylogenetic studies available. As in many instances Red Lists either do not mention authorship of taxa or use outdated versions, we followed Index Fungorum and MycoBank in all cases.

2.3. Distribution Data

Data on milkcaps distribution were collected from primary and secondary literature (taxonomic articles, checklists, review papers, monographs) and from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility database (https://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 5 April 2021)), that contains many unpublished records of fungal species. Dubious and/or unconfirmed occurrence records were marked as such and discussed in some cases. For the names of geopolitical entities, we followed The World Factbook (https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/ (accessed on 6 April 2021)). Although put together with care and considering all available records, the milkcaps distribution information reported in Table 1 is not intended as a comprehensive compilation of occurrence records for each single species, but rather as indicative of the geographic range of a species. The purpose is to offer the possibility of a rapid appreciation of the extension for which the conservation status assessment was carried out with respect to the distribution range of selected species.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Efforts in Macrofungi Conservation

The history of fungal conservation is by no means a long one. With a few noticeable exceptions—such as the attention raised by the decline of lichens and other groups of fungi caused by changes in land usage and pollution—it is not until 1985 that teams of researchers started to collaborate to pursue their work in this field in an internationally organized manner. In that year, the European Council for Conservation of Fungi (ECCF), the world’s oldest entity devoted specifically to fungal conservation was created (www.eccf.eu/ (accessed on 7 April 2021)). Mycological societies, in Europe and elsewhere, began to establish special committees dedicated to conservation, and seminal books appeared that mapped local experiences and strived to lighten the path for future action. “In different parts of the world there are several threats to fungi and fungal diversity that prompt thoughts of conservation. However, it is not self-evident whether and how fungi themselves can be conserved. Perhaps the emphasis should be placed on conservation of the site, or the habitat, or the host?” wrote the editors of Fungal Conservation, Issues and Solutions, the first comprehensive treatment on the subject, highlighting issues that are still very actual, indeed [50]. Importantly, at the end of the 1980s and then in the 1990s, several European countries started to set national Red Lists dedicated to macrofungi [29].

About twenty years ago, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) established the first specialist groups dealing with the conservation of fungi in the framework of its Species Survival Commission (SSC). This was a most significant key development in fungal conservation because it raised awareness of the need to protect fungi at a new level, comparable to that devoted to plants and animals, something never achieved before. The IUCN Species Survival Commission has now five distinct fungal specialist groups: Chytrid, Zygomycete, Downy Mildew, and Slime Mold; Cup-fungus, Truffle, and Ally; Lichen; Mushroom, Bracket, and Puffball; Rust and Smut (https://www.iucn.org/commissions/ssc-groups/plants-fungi/fungi (accessed on 5 April 2021)). The SSC has also a Fungal Conservation Committee (FCC), that aims “to raise awareness of the importance of fungi and the need to conserve them, enhance coordination among the fungal and the broader conservation communities, and foster action,” (https://www.iucn.org/commissions/species-survival-commission/about/ssc-committees/fungal-conservation-committee (accessed on 5 April 2021)).

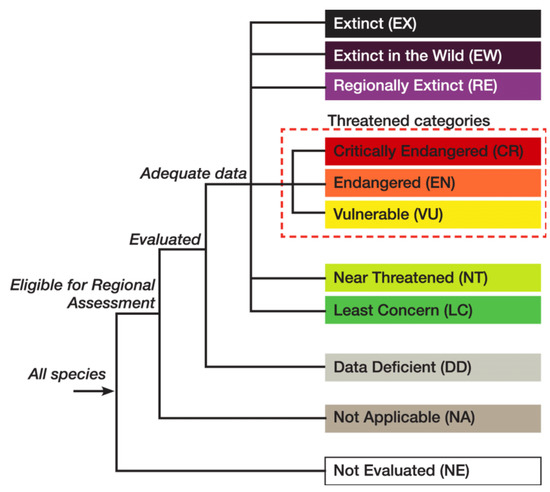

IUCN regularly evaluates the risk of extinction and other levels of threats different species of living organisms are facing. These assessments are conducted using a standardized platform of criteria [32], classifying each species into one of 11 categories (Extinct, Extinct in the Wild, Regionally Extinct, Critically Endangered, Endangered, Vulnerable, Near Threatened, Least Concern, Data Deficient, Not Applicable, Not Evaluated; see Figure 1). The suitability of the application of IUCN criteria to fungi has been subject to some discussion, as detailed below. The current (September 2021) Red List of Threatened Species has a total of 545 species, of which 424 are Agaricomycetes and 262 are classified as ‘threatened’ (i.e., CR, EN or VU) (https://www.iucnredlist.org/statistics (accessed on 13 September 2021)). The IUCN-sponsored Global Fungal Red List Initiative (http://iucn.ekoo.se/en/iucn/welcome (accessed on 13 September 2021)) is actively working to coordinate the inputs from the wider mycological community, including amateurs, in order to assess the largest possible number of fungi from all major taxonomic groups for publication in the IUCN Red List [51]. Over 2050 species of fungi have been ‘nominated’ to date (September 2021) from 219 countries, of which about 740 have been proposed for assessment, the first stage of the evaluation process of the conservation status of the selected fungal species.

Figure 1.

IUCN Red List Categories. For a description of each of the global IUCN Red List Categories go to: http://www.iucnredlist.org/technical-documents/categories-and-criteria/2001-categories-criteria#categories (accessed on 5 April 2021).

3.2. Milkcaps Diversity: A Global Perspective

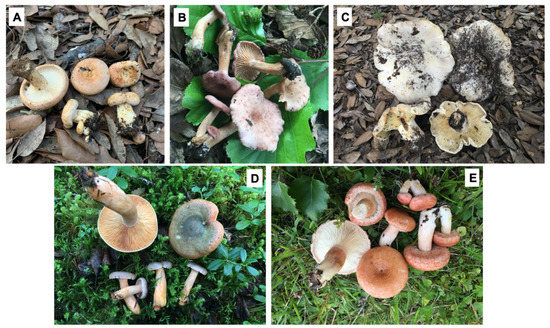

Currently, about 450 species of Lactarius (Figure 2) have been described, but the real number could be higher than 700 [52]. Not surprisingly, diversity in Europe and North America is fairly well known with respect to other areas, but even in these regions much remains to do. For example, several recent studies have shown the occurrence of cryptic or pseudocryptic species, depicting a more complex scenario in some instances. Moreover, intercontinental conspecificity is still an unresolved matter in many cases, as discussed more in detail below. While new species are occasionally being still described from Europe and North America [34,53], most of the novelties come from Southeast Asia, India, and China. Focused studies in these areas, often carried out by international teams, are revealing a host of new species, significantly expanding our understanding of the diversity of the genus, especially in tropical forests [54,55,56,57,58].

Figure 2.

Some of the species of milkcaps assessed in various Red Lists of macrofungi. (A) Lactarius mairei; (B) Lactarius lilacinus; (C) Lactifluus vellereus; (D) Lactarius fennoscandicus; (E) Lactarius torminosus. (A–C), various locations in Sardinia, Italy. (D,E), different locations in central Sweden.

Over 200 species of Lactifluus (Figure 2) are known worldwide, with a net prevalence in tropical areas. For comparison, while just nine species are present in Europe [22,23,24], some 76 species have been described from sub-Saharan Africa. Another important center of diversification of the genus is Southeast Asia, China, and India, a vast area from which at least 58 species are known [47]. The new frontline of research on Lactifluus diversity, however, seems to be the Neotropics, where the exploration of new habitats like the Brazilian Atlantic Forest on one side, and the fresh assessment of material from areas such as the Caribbean and Central America with molecular tools on the other, is revealing a somewhat surprisingly elevated number of new species, sometimes belonging to new sections [5,59,60]. Moreover, phylogenetic studies suggest that the real number of Lactifluus species could well surpass 500, indicating that most species still await discovery and description [52]. A new infrageneric classification of the genus, with four supported subgenera, namely Lactifluus, Lactariopsis, Gymnocarpi, and Pseudogymnocarpi, has been recently proposed on the basis of a multi-gene analysis [25]. Despite general acceptance of the new taxonomic organization of milkcaps, in several Red Data Lists species of Lactifluus continue to be listed as Lactarius, a fact due in part to the reality that Red Lists are updated and revised at intervals, sometimes of many years (see Table 1 and relevant notes). While the fact that numerous Lactifluus species are still present as Lactarius in some Red Lists does not have per se the smallest impact on the species conservation status, still, it is important for the sake of accuracy, reliability, and information utility to mention the current name according to internationally recognized nomenclature databases.

A relatively small number of Lactarius-related sequestrate taxa are known. These were traditionally hosted in the genera Arcangeliella Cavara and Zelleromyces Singer and Smith. About 15 accepted species (40 species in [61]) of Arcangeliella are known from Europe, North America, Australasia, and Africa. As for Zelleromyces, some 25 species have been described (17 in [61]), distributed across North America, South America, Eurasia, and Australasia. More recently, Josep Vidal has synonymized Zelleromyces with Arcangeliella, and proposed the new genus Gastrolactarius, with G. densus (R. Heim) J.M. Vidal as the type species, to include secotioid taxa [62]. However, all the sequestrate latex-bleeding forms mentioned above have been ultimately reconducted within Lactarius on the basis of molecular studies (see [1] and references therein), although the use of previous generic names continues in some instances (see Table 1 and relevant notes). In Europe, seven sequestrate Lactarius species are currently recognized [63]. A new species of hypogeous sequestrate milkcap, Lactarius taedae Silva-Filho, Sulzbacher, and Wartchow has been recently described from Brazil, apparently linked to exotic Pinus spp., which raises intriguing questions about the natural ectomycorrhizal host range and/or the biogeographic origin of this species [64].

As for what concerns ectomycorrhizal host preferences, many Lactarius species display some level of host-specificity, forming ECMs with a single plant species, or with a single plant genus, or with plant genera belonging to the same family. Well known examples drawn from the European scenario comprise L. porninsis with Larix decidua, L. pyrogalus with Corylus avellana, L. cistophilus and L. tesquorum with Cistus and Halimium (both in the Cistaceae family), L. controversus with Salicaceae (e.g., [13,65,66]). On the contrary, Lactifluus species seem to be more generalist in their ectomycorrhizal relationships, usually entering in symbiosis with a range of host plants. For example, in Europe, Lf. volemus is associated with both deciduous and coniferous hosts, while Lf. vellereus is known to be mycorrhizal on Quercus, Fagus, and Betula [67]. However, it should be noted that even in those cases where a ‘typical’ ectomycorrhizal association can be recognized, the possibility for a given milkcap to enter into mutualistic symbiosis with additional/diverse hosts cannot be ruled out a priori. A relevant, interesting case is L. hepaticus, usually reported as linked to Pinus, but recently shown to enter into shared mycorrhizal network between Pinus and understory Halimium shrubs (Cistaceae) [68], or to occur also in pure Halimium stands [48].

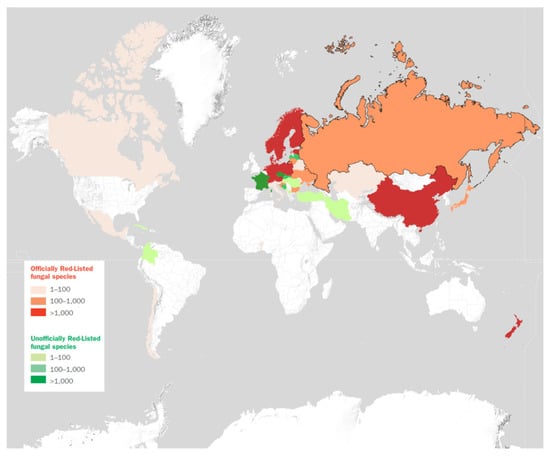

3.3. Milkcaps in Red Lists

Table 1 lists all species of Lactarius and Lactifluus quoted in Red Lists (35 in total) of macrofungi worldwide, either officially or unofficially published (with the possible exceptions of those species—presumably very few if any at all—present if the Red Lists we could not access, as described above). We admittedly lumped together data coming from global, national, and sometimes even regional (e.g., France) Red Lists. Although this might seem inappropriate, since species might be assessed differently depending on the geographical area covered by the specific Red List, we preferred at this stage to offer an overall view of how milkcaps are targeted for conservation measures, at any geographic level. The interested reader is referred to the Supplementary Materials to check specific assessments and their meaning. The total number of entries, 265, is rather impressive. Even subtracting some 40 species that are synonyms, illegitimate or poorly known/dubious taxa (see notes to Table 1), the remaining contingent makes over 30% of all described milkcaps, a rather significant percentage, indeed. A possible reason for this considerable attention towards milkcaps as for conservation enlisting, is the conspicuous appearance of these mushroom-forming basidiomycetes, and also their common use as popular edible products of the forest in many countries. For example, in Guatemala, out of a large number of milkcaps recorded in the country, only three, the edible and popular ones, are red-listed. Although the number of milkcap species assessed for conservation measures might seem elevated with respect to the overall number of known Lactarius/Lactifluus species, the level of consideration this important group of fungi is receiving is all but evenly distributed around the world, and even taxonomically. As shown in Figure 3, while a good share of European countries has an official or unofficial fungal Red List, large parts of the other continents still await the development of national red-listing projects. More in detail, no African country, with the exception of Benin, has a Red List devoted to fungi; in South America, only Chile and Colombia have carried out conservation assessments for at least some macrofungi. Other notably large countries, in some cases home to a rich biodiversity, that still lack a national Red List devoted to macrofungi are India, Brazil, the United States of America, and Australia. This bleak picture is somewhat mitigated by the fact that selected fungal species from these important areas are included in international Red Lists, such as that of IUCN and the Global Fungal Red List Initiative, or have been earmarked for assessment. Several North American milkcaps, listed in Table 1, for example, are included in the number (see [69]). Lactifluus species are severely underrepresented in Table 1. Since the center of diversification of the genus seems to be in tropical areas of Africa, America, and Asia, it is likely that the progress of conservation efforts is these areas will add more species to the global milkcap Red List (Table 1). Indeed, just 24 species of Lactifluus (including Lf. albivellus, Lf. corrugis, Lf. hygrophoroides, Lf. oedematopus, Lf. pergamenus, Lf. wangii, erroneously listed as Lactarius in relevant Red Lists) have been assessed, versus 241 species of Lactarius. While in some cases the absence of a fungal Red List might be due to a lack of fungal inventories, reference collections, and taxonomical knowledge in a country or region, in many other cases the reason for it must be reconducted to a cultural factor, i.e., the failure to accept Red Lists of fungi as a suitable tool for conservation management and, more in general, in understanding the ecological role of fungi and their need for protection as a vital component of virtually each and every ecosystem [31,70]. Moreover, the shortage of funding to initiate and accomplish fungal red-listing is a major obstacle in many cases. As a consequence of this, Table 1 lists a disproportionate number of European taxa, with a virtually complete inventory of the species described in the continent.

Figure 3.

Countries with published national fungal Red Lists. For more details, see https://stateoftheworldsfungi.org/ (accessed on 7 May 2021). Reprinted with permission from [31]. Copyright 2018 The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

National Red Lists generally use the international IUCN categories to reflect the levels of threats to fungi, but there are several exceptions. The German national Red List, for instance, includes distinct categories such as Threatened with Extinction (a species that is endangered to such a degree that it is likely to become extinct in the near future unless appropriate urgent action is taken) and Extremely Rare (extremely rare species, often with very local populations; total number of populations or individuals within populations do not show a long-term or short-term decline), which can easily be reconducted to corresponding IUCN threat categories in most cases (see Table 1 for further explanation). In other instances, a proper national Red List is still absent, being rather substituted by a host of regional lists, which collectively cover the entire national territory of a country. This is the case of France, for example (https://inpn.mnhn.fr/accueil/recherche-de-donnees/listes-rouges-especes (accessed on 20 April 2021)). Needless to say, the use of threat categories and criteria different from those officially adopted by IUCN makes comparison of the status of a given species as assessed in national Red Lists not straightforward, although in most cases conversion of the description of the level of menace a given species is facing to IUCN standards is possible.

When milkcaps nomenclature used in Red Lists is concerned, it can be safely stated that it is neither accurate nor up to date. As mentioned above, some 40 of the listed species are synonyms or taxa with unclear status. Moreover, in many cases, Lactifluus species are still assigned to Lactarius (see notes to Table 1). One example is paradigmatic of the general confusion and lack of accuracy. Three European Red Lists (ECCF, France, Switzerland) plus the Chinese one mention Lactifluus luteolus. Of these, all European Red Lists quote it as Lactarius luteolus, and all four are wrong, because the current name of the European taxon is Lactifluus brunneoviolascens (Bon) Verbeken, being Lf. luteolus Peck the correct name for a North American species [4,47]. However, as mentioned above, this is due in part to the fact that Red Lists are updated and revised periodically, and the time span of the Red Lists we examined is considerably large (starting from Malta, published in 1989, see Supplementary Materials). For example, while the most recent Swiss Red List was published in 2007, Lf. brunneoviolascens was assigned to the new genus only in 2012. Thus, some of the inertia towards nomenclatural standard references found in fungal Red List is explicable and, to some extent, unavoidable.

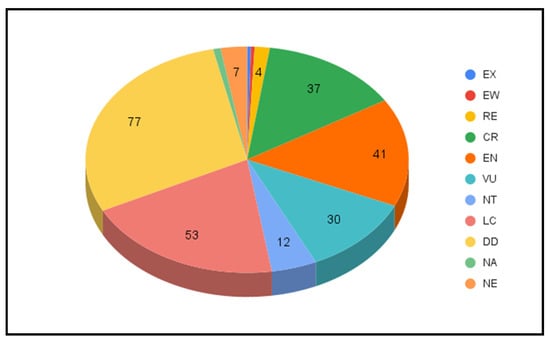

Figure 4 depicts an overall view of milkcaps status of conservation, drafted on the basis of the data reported in Table 1. As most species are present in more than one Red List (up to 18 in the case of L. lilacinus), sometimes evaluated with very different risk categories, due to different status and trends that exists considering different zones and geographical level of distributions, in our analysis each species was assigned to the group corresponding to the highest level of threat (as indicated by IUCN categories, see Figure 1) among those mentioned in the relevant Red Lists. For example, L. aspideus is currently assessed as Critically Endangered (CR) in at least one region of France (see above for an explanation of the French Red List structure), Endangered (EN) in Albania and Switzerland, Vulnerable in The Netherlands (KW) and Poland (V), and Least Concern (LC) in several other European countries. In this case, we assigned L. aspideus to the CR overall category, without attempting to ‘average’ the level of risk on the basis for example of territory extension or similar considerations. This is admittedly an arbitrary decision, but the scope of the present study is not to independently evaluate the conservation status of milkcaps, but rather to offer a critical overview of the state-of-the-art. On the other hand, it should be noted that ECCF assessed L. aspideus among its list of candidate species to enter a European Red List of endangered macrofungi as LC. This fact highlights the distance that might exist between global and local assessment of the conservation status of given taxa and calls for the weighed co-existence of international and national (or even regional) Red Lists, at least in the case of widespread species. Indeed, the assessment of the conservation status of a species over a wide territory following current procedures and standards, might end up minimizing the level of threat faced by the same species in significant parts of its distribution, as the case of L. aspideus exemplifies. IUCN has emitted special guidelines for the drafting of regional and national Red Lists adopting standardized criteria [71].

Figure 4.

Pie chart showing the number of species of milkcaps for each one of the IUCN categories (see main text and Table 1 for further details). Total number of species = 265, EX = 1 species, EW = 1 species, NA = 2 species.

The only two species that are listed as ‘Extinct’ (EX) at national level or proposed as ‘Extinct in the Wild’ (EW) in Table 1, are L. maruiaensis and L. ogasawarashimensis. Assessed as EW (preliminary category) for the Global Fungal Red List Initiative and as ‘Nationally Critical’ for the New Zealand Threat Classification System, L. maruiaensis was first collected in 1968 and described by McNabb in 1971, that studied material collected under Nothofagus at Spring Junction, in New Zealand’s South Island [72]; (Figure 5). In his assessment of the species status for the Global Fungal Red List Initiative, Patrick Leonard stated: “The area where it was originally found at Springs Junction has undergone rapid land use change with native forest and low intensity grazing being replaced by high intensity dairy farming”, and “The species has not been seen for 50 years and it is reasonable to suppose it is extinct,” (http://iucn.ekoo.se/iucn/species_view/316234/ (accessed on 13 September 2021)) However, the NYBG Steere Herbarium holds a sample (NY Barcode: 114109) collected by Roy Halling in 1992, at the Kaimanawa Forest Park, in the North Island. It is, therefore, possible that the species, indisputably rare, might still exist in areas distant from the typical location. L. ogasawarashimensis is a really mysterious taxon. Currently, it is listed as ‘extinct’ in the Japanese Red List (see Supplementary Materials). Described by Seiya Ito and Sanshi Imai in 1940 on the basis of material collected in Chichijima Island, in the Japanese Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands, it has never been found again and is, therefore, considered extinct. No voucher specimens exist [73]. Reportedly in ectomycorrhizal association with Pinus liuchuensis, introduced in the Ogasawara Islands, Ito and Imai noted that L. ogasawarashimensis occurrs “in mixing with L. sanguifluus and it is closely related with the last one,” but it is easily distinguished by the scarce and blue-colored latex [74].

Figure 5.

New Zealand’s threatened milkcaps. (A) Lactarius novae-zelandiae in habitat; (B) L. novae-zelandiae, preserved specimen (New Zealand Fungarium, PDD 106047); (C) Lactarius maruiaensis, holotype (New Zealand Fungarium, PDD 26531); (D) L. maruiaensis, drawing of holotype (New Zealand Fungarium, PDD 26531). Reproduced with permission. Copyright: (A,B,D), Jerry Cooper/Landcare Research New Zealand Limited; (C), Landcare Research New Zealand Limited.

Another small group of species listed in Table 1 have a more or less ample European distribution, with various degrees of conservation status, but are considered extinct in part of their range (Regionally Extinct, RE, or equivalent). The group includes L. acris, L. roseozonatus, L. sphagneti, and L. violascens, all of which disappeared from The Netherlands (VN). Other relevant cases cited in literature but not considered in any Red Lists concern L. scrobiculatus, probably extinct in Great Britain [75], and Lf. volemus, reported as extinct in the Flanders [67]. On the other hand, the word ‘extinction’ (often applied nationally if a species has not been recorded in the last 50 years) not necessarily means that a fungus has disappeared for ever. L. scoticus, believed extinct in Britain three decades ago [76], is currently considered as ‘vulnerable’ on the basis of the last available assessment of the species in the country [77], being reported only rarely and just from Scotland [75]. Although the significance of local extinction or the establishment of severely fragmented ranges in fungi is still not well understood in terms of population dynamics and gene flow [70], the vanishing of a fungal species even at the peripheral part of its distribution is alarming and should be carefully studied, as it might be due to ecological changes that could extend, although unnoticed, beyond the area where extinction took place.

Keeping the focus on threatened species, 37 milkcaps are listed as Critically Endangered (CR, or equivalent level of threat) and 41 as Endangered (EN), respectively (Figure 4). A group of five African species of Lactarius (L. aurantifolius, L. chamaeleontinus, L. foetens, L. miniatescens, L. rufomarginatus) have been assessed as CR when compiling the Benin Red List, published in 2011 [78]. Of these, L. rufomarginatus is apparently restricted to a few localities of Benin, where it occurs in riparian forests with Berlinia, Lonchocarpus, Uapaca and Pterocarpus [17]. Two other species, L. foetens and L. miniatescens, share the same habitat with L. rufomarginatus in Benin, occurring in the riverine forests of the Bassila region [78], but are also known from Togo [17]. Finally, L. chamaeleontinus and L. aurantifolius occupy a more widespread African range, although their distribution in Benin is punctiform, being reported only from the riparian gallery forest at Bassila and from the forest at the Kota waterfalls, respectively [78]. The conservation measures proposed for the CR Benin milkcaps hinge on the preservation of the fragile habitat where they occur, in particular the riparian forest ecosystems. “For their survival, they need improved legal protection of this already classified, but threatened forest,” underlined the authors of the Benin Red List [78].

Among the EN species, a special case is that of Lactarius novae-zelandiae. This striking milkcap is endemic of New Zealand, where it is apparently ectomycorrhizal with Fuscospora truncata (Colenso) Heenan and Smissen (Nothofagus truncata (Colenso) Cockayne is a synonym), growing in relatively mature forests (Figure 5). Two small populations have been identified, one in Karamea on the west coast of South Island, and a second at Lower Hutt, North Island, for a total of five locations. The species was described by McNabb in 1971 from Karamea [72] and since then this mushroom was recorded only very rarely, and never more from the type locality, despite that it produces large and conspicuous sporocarps and has been extensively searched for. Three observations are present in iNaturalist (see below), from 2015 to 2018. It is currently believed that the range of L. novae-zelandiae might have shrunk, mostly because of habitat modification. “It appears that the appropriate habitat at the type locality in Karamea has been much reduced by bushland reclamation for dairy farming, both at Umere Road and at Granite Creek where McNabb made his original collections, however, some suitable habitat may remain in the more inaccessible areas of the Karamea gorge,” recently wrote Leonard and Cooper [21]. The species is currently assessed EN under IUCN criteria B, C and D, with less than 100 mature individuals estimated, while identified conservation actions include protecting mature Fuscospora truncata forests (http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/full/80188416/0 (accessed on 30 July 2021)).

3.4. Protecting Milkcaps

To date, very few milkcaps are protected by law. Generally speaking, species that have been the focus of protection measures are edible, and regulations have been introduced to avoid excessive picking and/or alteration of habitat by means of destructive collection procedures, such as litter removal. For example, in Cyprus, L. deliciosus is eagerly searched in Pinus forests, where it is often buried under a thick layer of fallen pine needles; local Forest Law permits the collection of these mushrooms, “provided that no rake or other agricultural tool is used in the harvesting process” (http://www.moa.gov.cy/moa/fd/fd.nsf/fd67_en/fd67_en?OpenDocument (accessed on 15 June 2021)). In Croatia, a national law approved in 2002 declares as protected, among scores of other fungal species, L. acris (assessed as NT in the 2008 Croatian Red List), and L. controversus (not red-listed) (http://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC113201 (accessed on 15 June 2021)). Moreover, the ordinance regulates the collection and trade of the following species: L. deliciosus, L. deterrimus, L. hemicyaneus, L. quieticolor, L. salmonicolor, L. sanguifluus, and L. semisanguifluus (none red-listed). Despite the fact that several studies have shown no long-term effects of intensive harvesting on sporocarp production by macrofungi (see [79]), it is obvious that mushroom foraging (a more and more popular practice in many areas of the world), it is inevitably associated with some negative impact on ecosystems, due to trampling and damage to soil profile, for example. More in general, protection of habitats were endangered milkcaps and other macrofungi are found is pivotal for the conservation of these key microorganisms.

3.5. Milkcaps Distribution Data: The Good, the Bad, the Weird

Macrofungi distribution data, either at the global, national, or regional level, are essential in order to correctly assess the level of threat and to plan appropriate conservation measures, setting priorities and allotting the necessary resources. It might sound redundant to stress, but the first type of information needed to map the distribution of any organism, is to know which species is which and to use an unambiguous manner to indicate it. In the case of milkcaps, and of many other macrofungi groups, this is not to be taken for granted. Traditionally, indeed, several European names of species have been used to indicate North American and, more recently, Asian taxa, generating the false belief that many species of Lactarius and Lactifluus might have an intercontinental, and in some case worldwide, distribution and, conversely, underestimating fungal diversity in many understudied areas. Relevant examples are too numerous to be listed, but studies conducted in the last decade or so, supported by the integration of molecular and morphological techniques, have shown that intercontinental distribution in milkcaps seems to be much rarer than previously believed. Broad intercontinental, sometimes circumboreal, distribution has indeed been verified for a number of arctic-alpine species associated with Salix spp. (L. lanceolatus, L. nanus, L. salicis-reticulatae) and Betula (L. glyciosmus, L. pubescens), and also for some Picea associates (like L. badiosanguineus, L. repraesentaneus), and for some species linked to a wider range of host plants (e.g., L. controversus with Salicaceae, L. rufus with Pinus and Picea) [80,81]. On the other hand, the worldwide survey of Lactarius section Deliciosi (that includes many edible species) performed by Nuytinck and colleagues has revealed that “intercontinental conspecificity in this section seems much lower than assumed so far” [35]. According to researchers, no overlap could be shown between North America and Eurasia, while conspecificity could be demonstrated for L. deliciosus and L. sanguifluus occurring in both Europe and Asia [35]. Conspecificity was proved to be absent also in the case of Asian and American members of the large Lactarius subgenus Gerardii [44,82]. North American records of L. hepaticus most likely refer to the superficially similar L. badiosanguineus [80]. A number of other reports await clarification, as for example the recent record of the north European L. fennoscandicus in India [83]. The occurrence of fungal species in areas that are apparently very distant from their home range is always possible, of course, but these unusual findings must be substantiated by an exhaustive study, as recently happened with the collection of the rare L. flavaspideus—so far known only from Finland—in Italy [84]. The nonchalant use of established names for the identification of milkcaps in poorly explored regions is clearly based on the lack of a thorough analysis and interpretation of fungal macro- and microscopical characters, and of an accompanying comprehensive phylogenetic study based on molecular data. Several researchers are currently working, following this modern approach, to disentangle the knots of misapplied Lactarius and Lactifluus names in Asia and elsewhere (e.g., [36,37,49]). Meanwhile, the effect of the wrong adoption of European, and to a minor extent American, names for Asian milkcaps becomes manifest if one browses the Chinese Red List, which is further overly polluted with a vast number of taxa for which no evidence of their presence in China could be traced in the literature whatsoever. It is not clear to us how this Red List has been compiled, and if the milkcaps species that are included in it have been ever assessed as for their conservation status. Likely, many taxa names have crept in proceeding from older, generalist publications, not focused on specific fungal groups but rather describing the mycoflora of entire provinces and regions (e.g., [85]). On a separate note, one should not forget that many ectomycorrhizal fungal species, including several milkcaps, have been introduced with their host plants outside their original range [86]. Some of these occurrences, which of course have relevance from the conservation point of view, are noted in Table 1 (e.g., L. pubescens, L. rufus, L. torminosus).

Citizen science is a potentially rich source of species occurrence data that could be used both to map the distribution of given fungal taxa, including milkcaps, and to monitor their conservation status [87,88]. A number of citizen science initiatives focus on or encompass macrofungi. iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org/ (accessed on 13 September 2021)), for instance, is a large platform, with over 2.5 million registered users and some 47,000 milkcaps (Lactarius and Lactifluus combined) ‘observations’. On a smaller scale, other citizen science organizations are performing egregious work in fostering knowledge about macrofungi at a national level. Relevant examples of more or less long-running projects include Fungimap in Australia (https://fungimap.org.au/ (accessed on 18 May 2021)) and the Swedish Species Observation Centre (https://www.artportalen.se/ (accessed on 15 May 2021)). The contribution of citizen science to boost knowledge on macrofungi distribution and to promote their conservation is shown by the striking results of the Danish Fungal Atlas. Over a five year period, (2009–2013), the project generated over 235,000 records of Basidiomycota, adding 195,000 records to those from earlier periods; overall, 71 species of milkcaps, 197 fungal species new for Denmark and 15 species new to science were recorded [89]. Managed by the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, The Lost and Found Fungi (LAFF) project has run for six years, from mid 2014, aiming to “raising the profile of rare or potentially under-reported fungi” in the UK (http://fungi.myspecies.info/content/lost-and-found-fungi-project (accessed on 20 May 2021)). Focusing on little more than 100 species of Basidiomycota (no milkcaps, though), Ascomycota, rusts and lichens, LAFF resulted in a dataset of over 1500 records of 77 species, some of which (e.g., Godronia fuliginosa and Sporomega degenerans) have been rediscovered after a recording gap of over 50 years. Notwithstanding these virtuous examples, a recent analysis of the use of citizen science as a source of data for species distribution models has revealed “a notable under-use of plant, fungi, lichen and bryophyte public databases in the last decade in papers that model the distribution of species, as compared to the interest that they generate in CS [citizen science] programs”, a fact attributed by authors to the difficulty of identifying species of these taxonomic groups in the field [90]. For what concerns macrofungi, the best success stories mentioned above have clearly indicated that a strict collaboration between professional and amateur mycologists is paramount in order to build reliable datasets, to be used as a robust basis for conservation mycology initiatives (even iNaturalist has ‘identifiers’). More specifically, although milkcaps are not a particularly complex group as for species identification, the role of experts for the verification of collected specimens should remain pivotal. This, by no means, is to downplay the role of amateurs, that often are better than professional mycologists at identifying species, but it is a reality that in some cases morphological characters are not sufficient to discriminate between very close species, and only molecular tools can be resolutive. A relevant example is Lactifluus subvolemus Van de Putte & Verbeken, a recently described species occurring in Europe and very similar to Lf. volemus, with which intermediate forms exist [24]. The correct identification of cryptic species has significance also from the conservation point of view, of course. Given the endangered or vulnerable status of Lf. volemus in several European countries (Table 1), the fact that the species is actually a complex of related taxa (that includes Lf. oedematopus) with a still incompletely known distribution, poses conservation issues, as previously noticed [24]. More specifically, once further data are acquired on these and other cryptic milkcaps, conservation measures should be narrowed and made more focused.

3.6. Rare and Endangered, or Simply Poorly Known and Questionable?

A careful analysis of Table 1 reveals that several species of milkcaps whose validity or even existence is doubtful are listed in different national Red Data Books, under various conservation categories. Leaving aside established synonymies and illegitimate names (that are also present), relevant examples of poorly known species nevertheless considered valid include L. firmus, L. ogasawarashimensis (see above), L. obliquus, L. syringinus and L. terenopus. From our point of view, the reasons that brought these taxa under the focus of Red List compilers are unclear, given the fact that documentation on key issues (e.g., distribution and population size) regarding these species is virtually nonexistent. If rarity is ‘the’ criterion for inclusion in the list (and, we believe, it should be just one of the considered criteria), then, even restricting the view to Mediterranean Europe, other milkcaps should have their accession to the guild granted. For example, Lactarius castanopus (later moved to Lactifluus by Schwab [91]), described by Mauro Sarnari from Tuscany, Italy, to the best of our mention has never been found again after its first mention [92]. Lactarius purpureobadius is another intriguing case. First described by Malençon from Quercus forests in Morocco, the species has been later characterised by Maria Teresa Basso on the basis of Malençon’s herbarium material and new collections attributed to this taxon from Sardinia, Italy [93]. More recently, L. purpureobadius has been reported also from Spain [94], one of the very few known records for this species. For both L. castanopus and L. purpureobadius, no molecular data exist. Is it useful, or even appropriate, to have all these taxa earmarked for conservation measures? Our opinion is no. Indeed, we believe that before making it to any list, a minimum level of knowledge of a given species should be reached. Otherwise, the risk of inflating Red Lists with a plethora of names that are scarcely grounded on real data becomes concrete.

On the other hand, initiatives such as LAFF, launched at either national or international level and hinging on the competent help of volunteers, should become more common, determining if these and other unfrequently recorded species of macrofungi are genuinely rare, overlooked, or simply nonexistent. In other terms, a sort of filter should apply to poorly known species, striving to perform phylogenetic assessments and to establish baseline distribution datasets before admitting them to Red Lists. A species of Lactarius living in the Mediterranean area that would deserve such attentions as potentially very localized and, thus, endangered, is L. cyanopus [95]. The status of this taxon remains unclear, despite that some work on it has been carried out (even molecularly), establishing that it might be a sister species of L. sanguifluus and L. vinosus [96]. L. cyanopus is known only from a few locations in Italy and Spain, and the type locality has been destroyed by a fire years ago; further collections are necessary to ascertain its phylogenetic position and ecology, and to gather information that could lead to an accurate assessment of its conservation status.

The correct path that should lead a rare species to be the focus of Red List assessment and eventually conservation measures, in our opinion, is that indicated by Lactarius pseudoscrobiculatus. This Mediterranean species is distributed from Spain to the East Aegean Islands in association with Mediterranean Pinus and Cistaceae (Cistus spp., Halimium halimifolium) [48,97], and has been rarely reported, although it might be locally common (Pierre-Arthur Moreau, personal communication). Detailed morphoanatomical study of new collections and their comparison with original description, integrated by molecular phylogenetic analysis, has recently permitted to expand our understanding of the relationships of L. pseudoscrobiculatus within the genus, and to acquire much needed information on the geographic distribution and ecology of this ectomycorrhizal species [98]. Accordingly, L. pseudoscrobiculatus is currently under assessment by the Global Fungal Red List Initiative (listed as ‘Proposed’; see Table 1), with the justification: “Lactarius pseudoscrobiculatus is a very rare species with fragmentary distribution that grows in endangered areas in the area Mediterranean” (http://iucn.ekoo.se/iucn/species_view/483610/ (accessed on 25 May 2021)).

4. Conclusions

As the result of a gradual development over the last 40 years, fungi, and especially macrofungi, are finally in the spotlight of conservation biologists and stakeholders worldwide, and this is good news [99,100,101,102]. Constituting a not marginal part of the Basidiomycota diversity, and given their role as ectomycorrhizal symbionts in vast forest ecosystems and scrublands and, for many species, as edible non-timber forest products for numerous human peoples, milkcaps are going to be an important component of this radical change of perspective. The large number of species included in Red Lists worldwide, as shown in this work, demonstrates that they are not a ‘neglected’ group of macromycetes, and gives hope as for their future protection, which will necessarily hinge on the preservation of the habitats where these fascinating fungi thrive [79].

However, our study revealed also some shortcomings in the current process of assessment of milkcaps for insertion in Red Lists, at least from our perspective. In many cases, the application of wrong or outdated nomenclature, the mention of poorly known and insufficiently documented species, and the widespread use of European names to indicate different taxa (in some cases probably still undescribed species) occurring in other continents, has resulted in a huge confusion as for a global view on the conservation status of the group. We understand that names of species in Red Lists cannot follow the rapid changes in nomenclature that we are witnessing nowadays in a prompt way (see examples above), and that keeping using names that have been around for decades might be easier when Red Lists are intended as conservation tools handled by a mix of stakeholders with different background. However, nomenclature is important, because it frames the way we call living things at the light of current scientific knowledge, and if we wish to identify the species we intend to conserve, we should always try to use their correct names, any times a Red List is drafted and/or revised. As a side line, since the global change we are experiencing poses extraordinary stresses on habitats and the species that live there, fungal Red Lists should be update more regularly, in order to keep the pace with a rapidly evolving situation.

We call for a more sober and professional approach, with the involvement of competent experts, when assessing milkcaps (and any other fungi) for insertion in Red Lists. Despite the fact that specialists are in fact engaged in the drafting of many national and international Red Lists, the overall view reveals that this wise approach is not universally followed. Indeed, the risk of diminishing the inherent value of Red Lists—that make the first step towards the effective protection of any species—with the insertion of a plethora of names void of any taxonomic and/or ecological significance, is real. Another conservation challenge that will probably gain momentum in the following years, is the likely description of new cryptic taxa when complex species groups will be solved, presumably with the extensive use of molecular tools. In all these cases, the newly described species should not be inserted in Red Lists until sufficient data (for example, on distribution and population size) will be available to determine their status. Finally, although we have repeatedly stressed above the importance of reliable distribution data, one should not forget that these should be flanked by an estimate as accurate as possible of the status and trend of species, i.e., the assessment of the population size and how the size of the population is developing within the area being assessed.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su131810365/s1, Browsed fungal Red Lists: references and web links, Red-listed milkcaps, grouped by IUCN category of higher threat.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.R.; methodology, E.S., A.C.R.; formal analysis, O.C., M.L., E.S., A.C.R.; data curation, A.C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.R.; writing—review and editing, O.C., M.L., E.S.; visualization, O.C., M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting reported results are published either in the main article or as Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Buyck, B.; Hofstetter, V.; Verbeken, A.; Walleyn, R. 1919 Proposal to conserve Lactarius nom. cons. (Basidiomycota) with a conserved type. Taxon 2010, 59, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbe, D.; Wang, X.-H.; Verbeken, A. New combinations in Lactifluus. 2. L. subgen. Gerardii. Mycotaxon 2012, 119, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeken, A.; Nuytink, J.; Buyck, B. New combinations in Lactifluus. 1. L. subgenera Edules, Lactariopsis and Russulopsis. Mycotaxon 2011, 118, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeken, A.; Van de Putte, K.; De Crop, E. New combinations in Lactifluus. 3. L. subgenera Lactifluus and Piperati. Mycotaxon 2012, 120, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgat, L.; Courtecuisse, R.; De Crop, E.; Hampe, F.; Hofmann, T.A.; Manz, C.; Piepenbring, M.; Roy, M.; Verbeken, A. Lactifluus (Russulaceae) diversity in Central America and the Caribbean: Melting pot between realms. Persoonia 2020, 44, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, L.J. Lactarius. In Ectomycorrhizal Fungi. Key Genera in Profile; Cairney, J.W.G., Chambers, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 269–285. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi, A.C.; Comandini, O.; Kuyper, T.W. Ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity: Separating the wheat from the chaff. Fungal Divers. 2008, 33, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Comandini, O.; Rinaldi, A.C.; Kuyper, T.W. Measuring and estimating ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity: A continuous challenge. In Mycorrhiza: Occurrence in Natural and Restored Environments; Pagano, M., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 165–200. [Google Scholar]

- Homola, R.L.; Czapowskyj, M.M. Ectomycorrhizae of Maine 2. A listing of Lactarius with the associated hosts (with additional information on edibility). Life Sci. Agric. Exp. Stn. Bull. 1981, 779, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dell, B.; Havel, J.J.; Malajczuk, N. The Jarrah Forest: A Complex Mediterranean Ecosystem; Kluwer Aacademic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Comandini, O.; Pacioni, G.; Rinaldi, A.C. Fungi in ectomycorrhizal associations of silver fir (Abies alba Miller) in Central Italy. Mycorrhiza 1998, 7, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, U.; Oberwinkler, F.; Verbeken, A.; Pacioni, G.; Rinaldi, A.C.; Comandini, O. Lactarius ectomycorrhizae on Abies alba: Morphological description, molecular characterization, and taxonomic remarks. Mycologia 2000, 92, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuytinck, J.; Verbeken, A.; Leonardi, M.; Pacioni, G.; Rinaldi, A.C.; Comandini, O. Characterization of Lactarius tesquorum ectomycorrhizae on Cistus sp., and molecular phylogeny of related European Lactarius taxa. Mycologia 2004, 96, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, L.; Bandala, V.M. Revision of Lactarius from Mexico. Persoonia 2005, 18, 471–483. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.T.; Stubbe, D.; Verbeken, A.; Nuytinck, J.; Lumyong, S.; Desjardin, D.E. Lactarius in Northern Thailand: 2. Lactarius subgenus Plinthogali. Fungal Divers. 2007, 27, 61–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, G.M.; Halling, R.E. Macrofungi of Costa Rica. 2010. Available online: https://www.nybg.org/bsci/res/hall/ (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Verbeken, A.; Walleyn, R. Monograph of Lactarius in Tropical Africa; National Botanic Garden: Meise, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Comandini, O.; Erős-Honti, Z.; Jakucs, E.; Flores Arzú, R.; Leonardi, M.; Rinaldi, A.C. Molecular and morpho-anatomical description of mycorrhizas of Lactarius rimosellus on Quercus sp., with ethnomycological notes on Lactarius in Guatemala. Mycorrhiza 2012, 22, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores Arzú, R.; Comandini, O.; Rinaldi, A.C. A preliminary checklist of macrofungi of Guatemala, with notes on edibility and traditional knowledge. Mycosphere 2012, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Bhatt, R.P.; Stephenson, S.L. The current status of the family Russulaceae in the Uttarakhand Himalaya, India. Mycosphere 2012, 3, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, P.L.; Cooper, J.A. Lactarius Novae-Zelandiae. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017, e.T80188416A80188421. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T80188416A80188421.en (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Heilmann-Clausen, J.; Verbeken, A.; Vesterholt, J. The Genus Lactarius. Fungi of Northern Europe; Svampetryk and Danish Mycological Society: Greve, Denmark, 1998; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, M.T. Lactarius Pers. Fungi Europaei 7; Mykoflora: Alassio, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Putte, K.; Nuytinck, J.; De Crop, E.; Verbeken, A. Lactifluus volemus in Europe: Three species in one revealed by a multilocus genealogical approach, Bayesian species delimitation and morphology. Fungal Biol. 2016, 120, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Crop, E.; Nuytinck, J.; Van de Putte, K.; Wisitrassameewong, K.; Hackel, J.; Stubbe, D.; Hyde, K.D.; Roy, M.; Halling, R.E.; Moreau, P.-A.; et al. A multi-gene phylogeny of Lactifluus (Basidiomycota, Russulales) translated into a new infrageneric classification of the genus. Persoonia 2017, 38, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boa, E. Wild Edible Fungi: A Global Overview of Their Use and Importance to People; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Moreno, J.; Guerin-Laguette, A.; Rinaldi, A.C.; Yu, F.; Verbeken, A.; Hernàndez-Santiago, F.; Martìnez-Reyes, M. Edible ectomycorrhizal fungi: How can they contribute to forest sustainability, food security, biocultural conservation and mitigation of hunger and climate change? Plants People Planet 2021, 3, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin-Laguette, A.; Cummings, N.; Butler, R.C.; Willows, A.; Hesom-Williams, N.; Li, S.; Wang, Y. Lactarius deliciosus and Pinus radiata in New Zealand: Towards the development of innovative gourmet mushroom orchards. Mycorrhiza 2014, 24, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn-Irlet, B.; Heilmann-Clausen, J.; Genney, D.; Dahlberg, A. Guidance for Conservation of Macrofungi in Europe. European Council for the Conservation of Fungi. 2007. Available online: http://www.eccf.eu/Guidance_Fungi.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Heilmann-Clausen, J.; Barron, E.S.; Boddy, L.; Dahlberg, A.; Griffith, G.W.; Nordén, J.; Ovaskainen, O.; Perini, C.; Senn-Irlet, B.; Halme, P. A fungal perspective on conservation biology. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, K.J. (Ed.) State of the World’s Fungi 2018 Report; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 2018; Available online: https://stateoftheworldsfungi.org/ (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- IUCN. IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1, 2nd ed.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nuytinck, J.; Wang, X.H.; Verbeken, A. Descriptions and taxonomy of the Asian representatives of Lactarius sect. Deliciosi. Fungal Divers. 2006, 22, 171–203. [Google Scholar]

- Favre, A.; Guichard, C. Lactarius helodes nov. sp. Bull. Mycol. Bot. Dauphiné-Savoie 2002, 164, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nuytinck, J.; Verbeken, A.; Miller, S.L. Worldwide phylogeny of Lactarius section Deliciosi inferred from ITS and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene sequences. Mycologia 2007, 99, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbe, D.; Verbeken, A. Lactarius subg. Plinthogalus: The European taxa and American varieties of L. lignyotus re-evaluated. Mycologia 2012, 104, 1490–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-H. Type studies of Lactarius species published from China. Mycologia 2007, 99, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessette, A.E.; Harris, D.B.; Bessette, A.R. Milk Mushrooms of North America. A Field Identification Guide to the Genus Lactarius; Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bas, B. Les Lactaires en Franche-Comté: Généralités, Classification, Monographies, Cartographies, Toxicités & Recherches Scientifiques. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Franche-Comté, Besançon, France, 2016. Available online: http://mycofme.free.fr/publications/these_pharmacie_les_lactaires.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Della Maggiora, M.; Nuytinck, J. Lactifluus oedematopus e Lactifluus subvolemus, due specie poco conosciute raccolte in Toscana. Riv. Micol. 2018, 61, 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- De Crop, E.; Nuytinck, J.; Van de Putte, K.; Lecomte, M.; Eberhardt, U.; Verbeken, A. Lactifluus piperatus (Russulales, Basidiomycota) and allied species in Western Europe and a preliminary overview of the group worldwide. Mycol. Prog. 2014, 13, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Filho, A.G.S.; Sulzbacher, M.A.; Ferreira, R.J.; Baseia, I.G.; Wartchow, F. Lactarius taedae (Russulales): An unexpected new gasteroid fungus from Brazil. Phytotaxa 2018, 379, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methven, A.S. North American and European Species of Lactarius. Scr. Bot. Belgica 2013, 51, 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbe, D.; Nuytinck, J.; Verbeken, A. Critical assessment of the Lactarius gerardii species complex (Russulales). Fungal Biol. 2010, 114, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuytinck, J.; Verbeken, A. Morphology and taxonomy of the European species in Lactarius sect. Deliciosi (Russulales). Mycotaxon 2005, 92, 125–168. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Luo, Y.H.; Xu, K.; Xu, J.C.; Chamyuang, S.; Mortimer, P.E. Drivers of macrofungal composition and distribution in Yulong Snow Mountain, southwest China. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Crop, E.; Delgat, L.; Nuytinck, J.; Halling, R.E.; Verbeken, A. A short story of nearly everything in Lactifluus (Russulaceae). Fungal Syst. Evol. 2021, 7, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, M.; Furtado, A.N.M.; Comandini, O.; Geml, J.; Rinaldi, A.C. Halimium as an ectomycorrhizal symbiont. New records and an appreciation of known fungal diversity. Mycol. Prog. 2020, 19, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Putte, K.; Nuytinck, J.; Verbeken, A. Lactarius volemus (Russulales): From a traditional morphological species to a worldwide species complex. Scr. Bot. Belgica 2013, 51, 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D.; Nauta, M.M.; Evans, S.E.; Rotheroe, M. Fungal Conservation, Issues and Solutions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, G.M.M. Progress in conserving fungi. BG J. 2017, 14, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nuytinck, J.; De Crop, E.; Delgat, L.; Bafort, Q.; Rivas Ferreiro, M.; Verbeken, A.; Wang, X.-H. Recent insights in the phylogeny, species diversity and culinary uses of milkcap genera Lactarius and Lactifluus. In Mushrooms, Humans and Nature in a Changing World: Perspectives from Ecological, Agricultural and Social Sciences; Pérez-Moreno, J., Guerin-Laguette, A., Flores Arzú, R., Yu, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Nuytinck, J.; Ammirati, J.F. A new species of Lactarius sect. Deliciosi (Russulales, Basidiomycota) from western North America. Botany 2014, 92, 767–774. [Google Scholar]

- Das, K.; Verbeken, A.; Nuytinck, J. Morphology and phylogeny of four new Lactarius species from Himalayan India. Mycotaxon 2015, 130, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-H.; Nuytinck, J.; Verbeken, A. Lactarius vividus sp. nov. (Russulaceae, Russulales), a widely distributed edible mushroom in central and southern China. Phytotaxa 2015, 231, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisitrassameewong, K.; Nuytinck, J.; Thanh Le, H.; De Crop, E.; Hampe, F.; Hyde, K.D.; Verbeken, A. Lactarius subgenus Russularia (Russulaceae) in South-East Asia, 3: New diversity in Thailand and Vietnam. Phytotaxa 2015, 207, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-H. Three new species of Lactarius sect. Deliciosi from subalpine-alpine regions of central and southwestern China. Cryptogam. Mycol. 2016, 37, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Wissitrassameewong, K.; Park, M.S.; Verbeken, A.; Eimes, J.; Lim, Y.W. Taxonomic revision of the genus Lactarius (Russulales, Basidiomycota) in Korea. Fungal Divers. 2019, 95, 275–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgat, L.; Dierickx, G.; De Wilde, S.; Angelini, C.; De Crop, E.; De Lange, R.; Halling, R.; Manz, C.; Nuytinck, J.; Verbeken, A. Looks can be deceiving: The deceptive milkcaps (Lactifluus, Russulaceae) exhibit low morphological variance but harbour high genetic diversity. IMA Fungus 2019, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque Barbosa, J.A.É.; Delgat, L.; Elias, S.G.; Verbeken, A.; Neves, M.A.; de Carvalho, A.A., Jr. A new section, Lactifluus section Neotropicus (Russulaceae), and two new Lactifluus species from the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. System. Biodivers. 2020, 18, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P.M.; Cannon, P.F.; David, J.C.; Stalpers, J.A. (Eds.) Ainsworth and Bisby’s Dictionary of the Fungi, 10th ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, J.M. Arcangeliella borziana and A. stephensii, two gasteroid fungi often mistaken. A taxonomic revision of Lactarius-related sequestrate fungi. Rev. Catalana Micol. 2004, 26, 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, J.M.; Alvarado, P.; Loizides, M.; Konstantinidis, G.; Chachuła, P.; Mleczko, P.; Moreno, G.; Vizzini, A.; Krakhmalnyi, M.; Paz, A.; et al. A phylogenetic and taxonomic revision of sequestrate Russulaceae in Mediterranean and temperate Europe. Persoonia 2019, 42, 127–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Filho, A.G.S.; Sulzbacher, M.A.; Grebenc, T.; Wartchow, F. Not every edible orange milkcap is Lactarius deliciosus: First record of Lactarius quieticolor (sect. Deliciosi) from Brazil. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2020, 93, 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Comandini, O.; Contu, M.; Rinaldi, A.C. An overview of Cistus ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 2006, 16, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comandini, O.; Rinaldi, A.C. Lactarius cistophilus Bon & Trimbach + Cistus sp. Descr. Ectomycorrhizae 2008, 11/12, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeken, A.; Nuytinck, J.; Noordeloos, M.E. Russulales, part I. In Flora Agaricina Neerlandica; Nooerdeloos, M.E., Kuyper, T.W., Somhorst, I., Vellinga, E.C., Eds.; Candusso Editrice: Origgio, Italy, 2018; Volume 7, pp. 226–356. [Google Scholar]

- Buscardo, E.; Rodríguez-Echeverría, S.; Barrico, L.; García, M.Á.; Freitas, H.; Martín, M.P.; De Angelis, P.; Muller, L.A.H. Is the potential for the formation of common mycorrhizal networks influenced by fire frequency? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 46, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellinga, E.C.; Bérubé, J.; Castellano, M.; Mueller, G.M. Adding North American mushrooms to the IUCN Global Red List. Inoculum 2015, 66, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, A.; Mueller, G.M. Applying IUCN red-listing criteria for assessing and reporting on the conservation status of fungal species. Fungal Ecol. 2011, 4, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Guidelines for Application of IUCN Red List Criteria at Regional and National Levels: Version 4.0; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McNabb, R.F.R. The Russulaceae of New Zealand 1. Lactarius DC ex S. F. Gray. N. Z. J. Bot. 1971, 9, 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Castellano, M.A.; Orihara, T. The status of voucher specimens of mushroom species thought to be extinct from Japan. Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci. (Ser. B) 2018, 44, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S.; Imai, S. Fungi of the Bonin Islands. IV. Trans. Sapporo Nat. Hist. Soc. 1940, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kibby, G. British Milkcaps Lactarius & Lactifluus. Privately Published. 2014.

- Ing, B. A Provisional Red Data List of British Fungi. Mycologist 1992, 6, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Henrici, A.; Ing, B. Preliminary Assessment: Red Data List of threatened British Fungi. British Mycological Society. 2006. Available online: https://www.britmycolsoc.org.uk/application/files/2013/3537/5755/RDL_of_Threatened_British_Fungi.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Yorou, N.S.; De Kesel, A. Champignons supérieurs/Larger fungi. In Protection de la Nature en Afrique de l’Ouest: Une Liste Rouge pour le Bénin/Nature Conservation in West Africa: Red List for Benin; Neuenschwander, P., Sinsin, B., Goergen, G., Eds.; International Institute of Tropical Agriculture: Ibadan, Nigeria, 2011; pp. 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, A.; Genney, D.R.; Heilmann-Clausen, J. Developing a comprehensive strategy for fungal conservation in Europe: Current status and future needs. Fungal Ecol. 2010, 3, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barge, E.G.; Cripps, C.L. New reports, phylogenetic analysis, and a key to Lactarius Pers. in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem informed by molecular data. MycoKeys 2016, 15, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barge, E.G.; Cripps, C.L.; Osmundson, T.W. Systematics of the ectomycorrhizal genus Lactarius in the Rocky Mountain alpine zone. Mycologia 2016, 108, 414–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbe, D.; Le, H.T.; Wang, X.-H.; Nuytinck, J.; Van de Putte, K.; Verbeken, A. The Australasian species of Lactarius subgenus Gerardii (Russulales). Fungal Divers. 2012, 52, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K. Lactarius fennoscandicus (Russulaceae), a new record for India. Nelumbo 2013, 55, 214–218. [Google Scholar]

- Calledda, F.; Boerio, G.; Cartabia, M.; Carbone, M. Studio del genere Lactarius. 1° contributo. Lactarius flavoaspideus e prima segnalazione per l’Italia. Studio e tipificazione di Lactarius aspideus. Prime evidenze genetiche di Lactarius flavidus. Micol. Toscana 2020, 2, 9–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhishu, B.; Guoyang, Z.; Taihui, L. The Macrofungus flora of China’s Guangdong Province; Chinese University Press: Hong Kong, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vellinga, E.C.; Wolfe, B.E.; Pringle, A. Global patterns of ectomycorrhizal introductions. New Phytol. 2009, 181, 960–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryzenhout, M. The need to engage with citizen scientists to study the rich fungal biodiversity in South Africa. IMA Fungus 2015, 6, A58–A64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irga, P.J.; Barker, K.; Torpy, F.R. Conservation mycology in Australia and the potential role of citizen science. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilmann-Clausen, J.; Bruun, H.H.; Ejrnæs, R.; Frøslev, T.G.; Læssøe, T.; Petersen, J.H. How citizen science boosted primary knowledge on fungal biodiversity in Denmark. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 237, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.J.; Imbeau, L.; Marchand, P.; Mazerolle, M.J.; Darveau, M.; Fenton, N.J. Trends and gaps in the use of citizen science derived data as input for species distribution models: A quantitative review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0234587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, N. Nomenclatural novelties. Index Fungorum 2019, 409, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnari, M. Una nuova specie di Lactarius dell’area mediterranea Lactarius castanopus sp.nov. Riv. Micol. 1992, 35, 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, M.T. Revisione “Lactaires du Maroc”. In Compléments à la Flore des Champignons Supérieurs du Maroc de G. Malençon et R. Bertault; Maire, J.C., Moreau, P.-A., Robich, G., Eds.; CEMM: Nice, France, 2009; pp. 653–688. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-De-Gregorio, M.A.; Campos, J.C.; Illescas, T. Lactarius purpureobadius Malençon ex Basso, en España. Rev. Catalana Micol. 2012, 34, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, M.T. Lactarius cyanopus une nouvelle espéce de la sect. Dapetes Fries. Bull. Trimest. Soc. Mycol. Fr. 1998, 114, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Nuytinck, J.; Verbeken, A. Species delimitation and phylogenetic relationships in Lactarius section Deliciosi in Europe. Mycol. Res. 2007, 11, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basso, M.T. Contributo allo studio dei Lactarius mediterranei: L. cyanopus e L. pseudoscrobiculatus. Micol. Veg. Mediterr. 2001, 16, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Polemis, E.; Nuytinck, J.; Fryssouli, V.; Pera, U.; Zervakis, G.I. Phylogeny, ecology and distribution of the rare Mediterranean species Lactarius pseudoscrobiculatus (Basidiomycota, Russulales). Plant Syst. Evol. 2019, 305, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, P.K.; May, T.W. Conservation of New Zealand and Australian fungi. N. Z. J. Bot. 2003, 41, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, M.; Persiani, A.M.; Ambrosio, E.; Vizzini, A.; Venturella, G.; Donnini, D.; Angelini, P.; Di Piazza, S.; Pavarino, M.; Lunghini, D.; et al. Macrofungi as ecosystem resources: Conservation versus exploitation. Plant Biosyst. 2013, 147, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, T.W.; Cooper, J.A.; Dahlberg, A.; Furci, G.; Minter, D.W.; Mueller, G.M.; Pouliot, A.; Yang, Z. Recognition of the discipline of conservation mycology. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, T.; Wang, K.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, B.; Jiang, L.; et al. Assessment of the threatened status of macro-basidiomycetes in China. Biodivers. Sci. 2020, 28, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).