Abstract

Indigenous Peoples within Canada experience higher rates of food insecurity, as do undergraduate students attending post-secondary institutions. Few studies have investigated the determinants of food practices and preferences for Indigenous students living away from their households and local environments. An exploratory study was designed to investigate Indigenous students’ experiences accessing local food environments. Research objectives included exploring Indigenous students’ experiences within institutional and community food settings; and examining campus- and community-based supports addressing their unique needs. Semi-structured interviews took place with eight self-identified Indigenous students. Four service providers participated in a focus group that included stakeholders from the post-secondary institution and the local community. Thematic analysis was used to categorize results into individual, interpersonal, organizational and community levels, according to the socio-ecological model. Themes based on the students’ responses included food and nutrition knowledge, financial capacity, convenience, social influences, campus food environment, cultural connections, and institutional support. Those participating in the focus group discussed the importance of social supports and connections to improve Indigenous students’ food environments beyond institutional parameters. Results suggest that Indigenous students are more aware of individual and interpersonal peer environments, with limited awareness of community services and cultural connections beyond campus. Indigenous students and community members require increased organizational and community awareness to support urban Indigenous food environments and sustainably address the range of socio-ecological conditions impacting food security.

1. Introduction

Food insecurity has been identified as a concern on a number of Canadian campuses with 39%, or nearly 2 out of every 5 students being classified as food insecure [1]. With tuition fees in Canada tripling since the 1990s, many students are experiencing great financial pressures, leading to food insecurity [2]. Nearly every post-secondary institution within Canada has a campus food bank to support students with short-term emergency food assistance, but there is limited research on the issues and potential impacts of chronic food insecurity among students [1]. Food insecurity is associated with poorer physical and mental health outcomes and lower academic performance [3,4], yet few studies have investigated how post-secondary students experience food insecurity within diverse environments and the potential impacts on food choice. Most research within North America has quantitatively examined primarily transitory food insecurity and the utilization of campus-based emergency food assistance [1,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. University is a critical period for young adults regarding food choices as they develop a more independent relationship with food and adjust to new food environments. Authors from one study at the University of Saskatchewan have indicated that First Nations students experience significantly higher rates of food insecurity at 64% [16], yet the unique needs and experiences of Indigenous post-secondary students have yet to be explored.

Food insecurity is a determinant of health; it is associated with poorer health outcomes and has negative impacts on overall well-being [17,18]. It can also negatively affect mental health, as it has been associated with increased rates of anxiety, depression and feelings of shame associated with relying on emergency food assistance [19]. Food insecurity is defined as limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate, safe foods or the limited ability to acquire socially and culturally acceptable foods [20]. Food insecurity places a significant burden on Indigenous communities and post-secondary students [17,21]. Food insecurity can be chronic or transitory [22]. Chronic food insecurity is a persistent or long-term condition, which results from an inability to meet food requirements over an extended period of time. It is often related to inadequate nutrient intake, such as iron-deficiency anemia in adolescents, and lower intakes of nutrient-dense foods [23,24]. Transitory food insecurity is temporary, resulting from fluctuations in food availability and access due to variations in food production, income, and food prices [22]. For students, food insecurity in various forms and beyond these standardized definitions and categories can harmfully affect scholarly performance, participation in extracurricular activities and social and cultural connections [5].

Food insecurity data within Canada are obtained from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) [17]. The sample is meant to be representative; however, rates are likely underestimated as populations with increased susceptibilities are not represented, including Indigenous Peoples living on-reserve and residents of long-term care facilities [17]. Overall, national data from the latest 2017–2018 survey indicate that 12.7% of Canadians experienced food insecurity in the past twelve months [17]. Recent research during the COVID-19 pandemic from the Canadian Perspectives Survey revealed that rates of food insecurity are increasing, with 14.6% having experienced food insecurity [25]. Among First Nation communities, the First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study (FNFNES) measured food insecurity prevalence [25]. Results indicate that a far greater number of households (48%) experience food insecurity within the province of Ontario, for example [26]. The FNFNES data, however, does not include First Nation individuals living in urban areas, Inuit or Métis. The CCHS identified 28.2% of Indigenous households as food insecure [17], but locally within southwestern Ontario, prevalence rates have been found to be much higher at 55% among those living in urban areas [27]. These results demonstrate that Indigenous families and individuals are at minimum more than twice as likely to experience food insecurity compared to the national average [17,26].

Research conducted in Canada, the United States and Australia indicates that undergraduate student populations also frequently experience food insecurity, with rates as high as 43% in the U.S., 25–48% in Australia, and 39% in Canada [1,6,7,8,9,10,11,28]. According to students at Canadian post-secondary institutions, the most commonly reported factors contributing to food insecurity are housing and tuition costs [5]. Other factors include limited time and preparation knowledge; inadequate student funding; food accessibility; and limited facilities to prepare meals [5,12,13]. Only a handful of studies have included Indigenous students [1,5]. At the University of Manitoba, an alarming 75% of Indigenous students reported themselves to be food insecure, compared to the study’s overall prevalence rate of 35% [21]. Further research aimed at understanding why rates of food insecurity are so much higher among Indigenous students has been recommended [1,16].

Circumstances of food insecurity among Indigenous households are similarly associated with decreased dietary quality and diversity, potentially leading to increased risk for diet-related chronic conditions [29]. Prior to colonization, Indigenous diets were considered healthier when they included foods connected to the natural environment, and obtained through farming, hunting or foraging [26,30]. Few studies, however, have investigated the determinants of these food practices and preferences, particularly for Indigenous students living away from their households and local environments. In response, this study was designed to qualitatively examine Indigenous university students’ experiences within urban and institutional food environments. To date, there have not been any previous studies focused on the food practices of Indigenous university students exclusively. The purpose of this preliminary study was therefore to explore the experiences of self-identified Indigenous students and determinants of their eating behaviours on campus and within the surrounding urban community. A secondary aim of this study was to investigate institutional and community resources that may or may not support the needs of Indigenous students within these unique food environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework

The Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres (OFIFC) developed the Useful, Self-voicing, Access and Inter-relationality (USAI) research framework to encourage research that is community driven, relevant, faithful to Indigenous identity, useful, self-voiced, accessible and relation based [31]. This framework was chosen to guide the research process to ensure this study is consistent with Indigenous methodologies, recognizing that knowledge comes from all relations of people, past, present and future and lives in words, concepts, feelings and ideas. Indigenous methodologies can be used to create and disseminate Indigenous knowledge that is representative of the worldviews of Indigenous Peoples and responsive to Indigenous frameworks [32]. There are four guiding principles to the framework. The first principle is utility, or making sure the research is practical, relevant and provides direct benefits. Recommendations need to be relevant to research partners and the participants themselves. The second principle of self-voicing encourages communities to become involved in the research as the knowledge holders and creators. To adhere to these principles, this study was designed through consultation with community and campus research partners to emphasize the voices of Indigenous students in through the use of open-ended less structured interviews. Conveying results formally and informally with all participants, students and stakeholders at various events, meetings and workshops throughout the study period adhered to the third principle of access. With the support of the ISC, overall results were shared with participants and other interested students during a soup and bannock lunch event at the end of the study period. The final guiding principle of inter-relationality stresses the importance of historical context in producing knowledge. The research team had prior, established relationships with the community of Indigenous students and support staff at the University of Guelph and these connections were strengthened through the course of this study.

2.2. Study Population and Participation Description

The University of Guelph is considered a mid-size school with approximately 21,000 undergraduate students. At the time of recruitment, 352 self-identified Indigenous students were enrolled at the university (C. Wehkamp, personal communication). With the support of the students and staff at the Indigenous Student Centre (ISC) on campus, Indigenous students were recruited by an email sent to their student listserv. There were also advertisements in the ISC’s newsletter and posters displayed in various locations across campus. Eight undergraduate Indigenous students participated in this study (see Table 1). A sample size of 6–10 interviews is recommended for small qualitative research projects and to reach saturation, the point where no new themes emerge from the data [33]. Seven of the participants were female. Six lived off-campus in the city of Guelph. Two resided on-campus in residence. Two participants lived at home with their parents and six were living with roommates. It was the first post-secondary experience for all participants. Five of the eight participants were from nearby communities within southwestern Ontario, one from a northern reserve community. Students came from a variety of academic majors including nutrition, biological science, psychology, international development, business leadership, nutraceutical sciences and human kinetics. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by the first author who is trained in qualitative methods using a semi-structured interview guide which was reviewed by ISC staff and piloted with an Indigenous student (Table S1 Supplementary File). The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Post-interview notes were taken to reflect on situational data and incorporated into the analysis.

Table 1.

Interview Participant Description (n = 8).

To provide supplementary context to the Indigenous student interviews, members of the university and wider community working with Indigenous students or familiar with circumstances of food insecurity in the community were contacted directly by email to request their participation in a focus group. The focus group included four participants (see Table 2). A smaller focus group size of three to eight is recommended to generate rich discussion and manageability [33]. Two participants were employees of the University of Guelph and two worked for non-profit organizations in the Guelph community. These participants were selected for their unique experiences within the community and at the university. The first author who is trained in qualitative methods facilitated the focus group, following an unstructured series of open-ended questions that were shared with the wider research team to generate feedback (Table S2 Supplementary File). The focus group was audio-recorded with the permission of participants and transcribed verbatim. Pseudonyms were chosen for all twelve participants to maintain confidentiality and student participants were given the opportunity to review their transcripts as part of the analysis phase that included member checking.

Table 2.

Focus Group Participant Description (n = 4).

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Guelph Ethics Board (protocol 17-09-033).

2.3. Analysis

The analysis of the interview and focus group transcripts followed the six phases of thematic analysis [34]. Text files were first organized by the first author, then coded and analyzed using NVIVO for Mac with support from the research team. Codes were generated through the systematic identification of repeating patterns within the transcriptions. Themes were identified from the codes and organized into categorical levels based on the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) framework by the first and second authors and then shared with the research team and study partners.

3. Results

3.1. The Socio-Ecological Model Framework

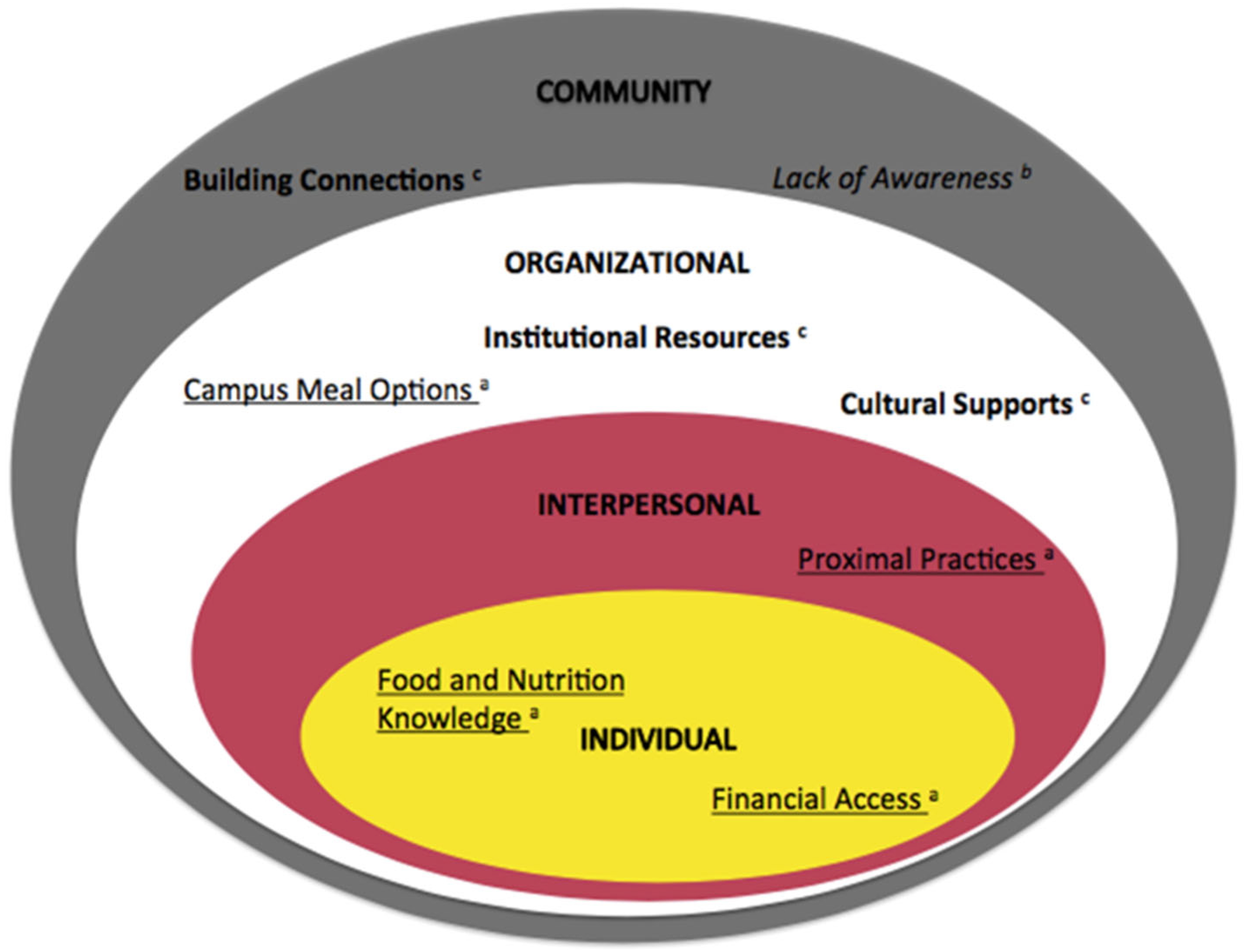

The SEM is a model framework that integrates multiple levels of influence including intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community and public policy influences [35]. It is based on the idea that health is influenced by many different components including physical environments, and social environments that are multi-dimensional and reciprocal. This model provides the opportunity to address multiple levels to target behaviour change—individual behaviour at the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels, organizational change at the community and institutional levels, and policy change at the systems level [35]—as it emphasizes the myriad of interactions between individuals and their environments [36]. The SEM model was chosen to structure the results from this study, as food environments are complex and affected by physical, social and personal dimensions such as knowledge, availability, economics and other factors. The SEM is a complex model that has a holistic view that is congruent with Indigenous methodologies, which also emphasize a more real-world, whole view to research [32]. Food environments are affected by many factors at various levels such as personal preference, living situation, food availability, food accessibility, and food prices. Previous research examining food consumption practices and use of traditional foods among Indigenous participants has adapted an ecological model [37]. An ecological model is fitting because food choices and practices are not simply influenced by individual factors, but also social and environmental factors and the interactions between the factors [37]. A four-level ecological model, similar to the model by Laberge Gaudid et al. (2014) was used as the conceptual framework to organize the factors anticipated to be associated with the experiences of Indigenous university students navigating various food systems and environments.

The results of the thematic analysis of the interviews and focus group for this study are organized and presented based on an adaptation of the SEM reflective of the themes identified (see Figure 1) according to participant group. Underlined themes in grouping A (N = 8) are based on results of the student interviews. Themes in italics indicate focus group themes in grouping B (N = 4), and bolded themes included the results from both participant groups in grouping C (N = 12). The framing of these ecological influences and their overlap according to these inter-related groupings are described in more detail in the next section.

Figure 1.

Adapted Socio-ecological Thematic Model Relative to Participant Findings across Ecological Influences. a Underlined themes are based on results of the student interviews. b Italicized themes indicate focus group themes. c Bolded themes included the results from both participant groups.

3.2. Individual Influences

3.2.1. Food and Nutrition Knowledge

Individual influences can be major determinants of food choice. Student participants were asked to describe where, why, and how they accessed their food. Six students talked extensively about food and nutrition. Tara, for example, gained nutrition knowledge through self-education and her program of study as a nutrition major. She explained that she learned by “googling recipes and seeing how other people did it. And then in some of my courses–they teach you specific skills.” Other avenues of gaining food knowledge came from learning with family members prior to university. Dana, a biological science major learned to cook, “from my mom mostly.” She took the initiative to learn more at university by “reading through cookbooks.”

Three participants discussed adjusting to healthier eating habits since starting university and living away from their social networks of families and communities for the first time. Cooking for one was described as challenging when planning meals and trying to maintain previously established schedules on their own. Nora, a social science major explained, “throughout my three years of university I gained like 80 pounds…but just within the past month I have changed… to lose weight, cut back and eat healthier.” Jane became more health conscious as a nutrition student. She said, “ever since starting school I’m on the vitamins depending on if I’m super stressed and I haven’t been eating very much.” Nora also discussed barriers to healthy eating associated with the stresses of being a student: “I definitely eat more when I’m in a semester versus in the summer I won’t eat as much… probably like 50% of the increase is just ‘cause of stress.”

3.2.2. Financial Access

Cost plays an enormous role in navigating food systems for participants living on- and off-campus. Students preferred to shop at locations with student discounts. Tara who lived off campus explained, “I pretty much solely get my food from Metro, because they do the student discount days.” According to Lindsey, budgeting strategies also influenced foods purchased at the grocery store: “I eat a lot more like meat and stuff at home than I eat here. I also eat a lot more vegetarian food here than I would at home…[because meat]…it’s expensive.” Other participants were interested in supporting ethical and sustainable food practices such as vegetarianism, but found their preferences limited by cost. Tara lamented, “I would love to obviously eat local all the time and buy organic stuff, but it’s expensive.” Another participant, Susie, expressed interest in buying fair trade and organic products, but also prioritized making sure she had enough food to eat over these ideals.

For students commuting to campus, many chose to eat at campus eateries and preferred the less expensive fast food options available. As Nora said, “fast food’s convenient on the road especially when you commute everyday.” Other students felt they needed to limit the number of times they purchased food on campus and would bring food they had prepared at home if living off-campus. Thomas talked about making sure he was prepared for long days on campus when he left his family home by bringing extra food, explaining, “I make food and bring it for lunches so I carry around a second bag just for lunch.”

3.3. Interpersonal Influences

Proximal Practices

University is a time when students are exposed to living with roommates for the first time. The majority of students who lived with their peers talked about the primarily positive influences their roommates had on food choices and preferences. Roommates were often described as helpful and generous in sharing meals and could unintentionally model healthy eating behaviours. Jane, a first-year student living in residence, referred to her roommate as, “very health conscious,” influencing her to make healthier choices when eating together on campus. Dana had similar experiences living away from campus, explaining that “one of the girls on my floor eats super healthy so whenever I go out with her you kind of feel guilty if you want something greasy.” At the same time, there were also challenges associated with peer practices when sharing meals and plans for social outings that would involve food. Roommates and friends frequently suggested outings that included fast foods and sweets. Lindsey explained, “you’re like one nudge away from, ‘ah I’ll eat out!’” Dana and her roommates lived next to take-out pizza and shared, “sometimes I’ll already eat dinner and then three hours later they come home and they’re like, ‘guys let’s get pizza’ and I just can’t say no.”

While living away from home for the first time, students talked about the support they felt from their families. All of the participants talked about visiting home during the school year and taking food back to school. Nora said, “my mom will try to make me eat while I’m at home or my partner’s family will try and offer food.” Families also provided financial assistance and regularly purchased groceries for those living off-campus. Tara’s parents lived a few hours north of Guelph and often they would by her “non perishable things.” Susie and Thomas lived full time with their immediate family and benefitted from the additional support. They had very different experiences from the rest of the participants with their mother doing the majority of the grocery shopping, although they were able to have some input on what was purchased. According to Susie, “if I want something or I’m interested in something, I’ll be like, ‘oh mom I kind of want this.’ She’s very flexible.” Their younger siblings would often take turns cooking, which in addition to support, according to Thomas, “would influence my food habits because they are vegetarian meals.”

3.4. Organizational Influences

3.4.1. Campus Meal Options

The University of Guelph offers many supports to undergraduate students and is top of the list for the best food in Canada. All students talked about purchasing food on campus regularly. For those living off-campus, the most commonly accessed eateries were those in the central area of campus, near the University Centre (UC). The UC acts as a hub for administrative services, student clubs, fast food and other restaurants. Tara said, “I have a commitment that requires me to be in the UC all the time…and I’ll buy food from the [cafeteria] in the UC or I will buy from the Bullring.” Others had similar habits and according to Susie, she preferred “the most cheap option” that included Subway or other fast food options. The experience of the two students living on-campus reflected their residence facilities. Ellen lived in a residence with no kitchen facilities. Jane’s residence included a full kitchen in each suite. Jane explained that, during the day, she would “grab lunch while out in the middle of the campus.” Ellen stated her preference for the residence cafeteria-style food locations in one residence that provided more options such as, “stir-fries and a better salad bar.” On weekends she explained that only one nearby residence was open and provided less healthy options such as “fried foods” that were not as preferable.

3.4.2. Institutional Resources

In terms of supports aimed at healthy eating, Tara commented, “I feel like there is a lot of resources on campus that direct students to where they need to go…even if you go to Loblaws, they have a registered dietitian.” Nora and Thomas also discussed noticing SNAP (Student Nutrition Awareness Program) posters in campus eating areas. Thomas expressed interest in the posters, as they advertise tips for healthy food choices for students. Nora and Dan expressed interest in taking nutrition courses to help increase their nutrition knowledge.

The campus student food bank provides access to emergency food and referrals to other supports and is available to all students, providing a maximum of 30 items per person each month. When asked about service limitations during the focus group, one of the food bank employees, Kelly, said: “I also don’t think our food bank is hitting everybody. You know people don’t know about [it] until maybe their 3rd or 4th year and then they might have been food insecure for a few years.” She went on to say, “I know of two people who are First Nations who use the service. That’s because, they’ve told me they are just thankful that the service is there for them if they need it.” Kelly highlighted the importance trying to meet the needs of all food bank visitors and wanting to learn from Indigenous students about: “some of the culturally appropriate items [the food bank] could be providing,” but has found that students are often hesitant to provide feedback. Members of the focus group talked about the stigma associated with accessing emergency food resources and that as a result it can be difficult for service providers to provide data on who is accessing the campus food bank. An Indigenous staff member at the University, Rachel, explained, “they may check the box that says ‘Caucasian’ because they are worried about discrimination in those services.”

3.4.3. Cultural Supports

The ISC is a designated location at the university for Indigenous students to study, meet other students, and participate in events often involving food. As a student, Nora discussed how the ISC informs her of events, such as the weekly lunches. Other participants did not feel that the ISC was as well known as it could be. Lindsey mentioned, “even soup and bannock [lunches]… is not always that busy, but I wish more people knew about it and would come...maybe they could post recipes or something like that, or have some kind of event, cooking event, cause they have a little kitchen in there”.

Soup and Bannock Wednesdays is a program that the Indigenous Student Society (ISS) runs from September to April. Students and other members of the campus community can enjoy a free hot lunch and socialize. Because it was offered each week at the same time, students felt it was not possible to attend regularly. Jane said: “I haven’t [been], but I see that they post it all the time and like I always want to go, but I just can’t find the time.” Four other participants who lived both on- and off-campus expressed their interest, but had not yet attended either.

During the focus group, Rachel talked about what she experienced working with student programming and the ISC supports those who are interested in learning about traditional foods and feeling connected to culture. She explaining that student would often, “share their traditions with one another because it’s very diverse across the First Nations, Métis populations.” For the lunch and other events, the ISC was working to increase knowledge of traditional foods. Rachel said, “the [Centre] works closely with Hospitality Services on campus and gives them recipes and works with them on menus for key times of the year like Aboriginal Awareness Week.” Rachel also discussed barriers Indigenous university students may face, stating that “a lot of students are urban, are not coming from remote locations, remote communities. They didn’t grow up eating [traditional] foods. For them, it’s not something they even expect.”

3.5. Community Influences

3.5.1. Lack of Awareness

From the perspectives of the focus group participants, there were many perceived barriers that were discussed based on their interaction with students. A staff member of an off-campus agency, Drew talked during the focus group about a lack of awareness with regard to emergency food assistance and access off-campus, stating: “whether they be Indigenous or not… probably pretty much mostly trapped in this kinda bubble here [at the university],… so they’re not seeing outside into the community.” Rachel added: “they don’t realize they can access services other than the on-campus food bank… it’s not necessarily publicly known, but it is made known to our students, that [the Centre] has a pantry… it’s stocked by our [ISS].” Drew and Rachel both sensed it was common for students to access campus services and resources almost exclusively, yet since many live off-campus, they are considered part of the wider urban Indigenous community and are able to access the city’s emergency and other community-based food programming. Focus group participants discussed the network of local service providers who share connections between resources. Kelly described a local collective of emergency food providers in Guelph that, “share resources with each other…. [and] share knowledge.” Rachel spoke about barriers students perceive, stating: “they [say] I’m registered with the student food bank, so I don’t qualify anywhere else…that’s just a perceived barrier. That doesn’t actually exist but letting them know these services exist.”

3.5.2. Building Connections

As part of their interviews, all twelve participants were asked to reflect on their own personal experiences on and off-campus and make recommendations on how to build linkages and overcome barriers that impacting the food security of Indigenous students. Student recommendations were generally conveyed as positive changes to support individual food choices and environments on campus. The focus group participants discussed the importance of building relationships and connections across food systems and communities.

Indigenous students provided ideas and suggestions for improving food accessibility and availability on- and off-campus. Nora recommended, “when you’re dealing with a university population…you know students are choosing convenience over nutrition. I would love the university to have some kind of wellness-like education on food and how to feed yourself properly…maybe the resources and knowledge is out there but students don’t know where to find it.” Nora went on to suggest that these additional supports may be most beneficial during the first year, as students are transitioning. Two other students thought establishing a farmer’s market on campus would increase accessibility to fresh locally-grown produce. Tara suggested, “having a student day for local farmers to… get it more out there so people would maybe buy more and then the price won’t be as high.” Students also provided recommendations for knowledge sharing around food utilization at the ISC. Lindsey suggested, “monthly cooking session with the Elders would be cool.” Other students had ideas related to food literacy and budgeting. Susie proposed, “some sort of club where people came and made their food together and that way it was cheaper cause you buy bulk things.”

Focus group participants talked about building connections through social support could provide Indigenous students with greater access to food resources and other social supports on and off-campus, bearing in mind, as Rachel cautioned, “being respectful of their choices and their journey with their identity. They may not be ready to engage in their Indigenous heritage yet.” Rachel emphasized creating a support system and “finding that balance of where students are at and what they are looking for when it comes to financial security and food security. The students…that are struggling with access to healthy, affordable foods are not necessarily thinking traditional foods.” Rachel also mentioned the importance of creating connections for students by “making those connections with community and with community events like the feasts.”

A member of the local urban Indigenous community, Olivia, talked about events aimed at connecting a diverse group of individuals around food. She explained that local Indigenous Elders and others organize “seasonal feasts” that are conducted according to “traditional ways in an urban setting and a community that has a combination of First Nations, Métis and Inuit.” Feasts occur four times a year and “everybody will bring a dish…we make sure there is core traditional foods present and there is nothing left over.” When asked about students attending, Olivia said “we do see some university students participate,” but awareness is lacking that, “there’s more available to them than just what’s on campus…to get them out of the campus bubble.” For Indigenous students living away from their families and social supports, feasts and other community events create the opportunity for making connections through learning according to Olivia, in a “safe, relaxed, non-pressured” community environment.

4. Discussion

The SEM was used as a framework to explore the various influences, individual, interpersonal and institutional that affect Indigenous students’ food environments. The findings incorporate the unique perspectives of Indigenous students and community supporters to provide guidance on how institutional and community food environments can influence food choice and access on and off-campus. Students talked about issues of food literacy and financial constraints at an individual level. Social circumstances, such as family and peer practices also influenced dietary patterns, both negatively and positively. Campus meal options and other resources at the institutional level were shared by student participants. Members of the focus group discussed at greater length the importance of cultural and social supports for students on and off-campus and advocated for greater awareness of events and services within the urban Indigenous community and off campus agencies providing emergency food provision.

These overall findings are comparable with recent research on post-secondary food systems, but also provide some novel insights on the perspectives of Indigenous university students. Unlike the many previous studies that have focused on quantifying individual circumstances of food insecurity, this study has aimed to raise awareness about the importance of community supports beyond institutions in supporting the collective well-being of Indigenous students. A limitation of this study, however, was the homogeneity of the student participants, leading to an over-representation of those living off-campus, proportionate to those students living on-campus. Seven of the eight interview student participants were also female, which limits the insight into the potential gender differences related to food environments and food security in these settings. Students who participated in interviews could likely have been interested in the topics of food and nutrition, which may differ from the wider group of Indigenous students. As such, the results have limited generalizability to other universities and Indigenous students as a diverse group.

Previously, the SEM has been used as a theoretical behaviour model with other student populations lending evidence to the importance of basing intervention strategies on multi-level approaches [38,39,40]. At the individual level, similar results have been described at other Canadian institutions in terms of food and nutrition knowledge or literacy. Wilson and colleagues (2017) reported 63% of undergraduate students felt comfortable preparing meals [41]. As most students in the current study were beyond their first year, it could be expected they would have increased food preparation or literacy skills. As other studies have reported, students who lived away from their parental home beyond one year had higher food skills scores [42]. Another study that examined students’ food patterns and preferences suggested the greatest determinant to purchasing food on campus was convenience [43]. Food costs are also discussed most commonly as a major influence on dietary choice [3,38], with students from a European study most often purchasing the least expensive options, even if they are perceived as unhealthy [44]. One fifth of students from another Canadian university similarly identified cost as a major factor affecting their access to food, leading to circumstances of self-reported food insecurity [5].

Whether living on or off-campus, roommates, family, and friends have been identified as having both negative and positive influences on students’ food choices [34,39,40]. In our study, Indigenous students discussed how peers and family encouraged them to eat healthier, which could lead participants to make impulsive decisions such as eating out more frequently. These sharing practices are discussed in the literature as integral aspects of interpersonal relationships [45]. Other studies have described more generally institutional influences on post-secondary food environments, referring mainly to the availability of food on campus [5,42]. Indigenous student participants at the University of Guelph talked about regularly accessing food on campus whether or not they were living in residence, but not as consistently about sources of food within the wider community and city. Recommendations that Indigenous students made to improve their food environments were similar to those expressed by food-insecure students at other Canadian institutions such as establishing collective kitchens, grocery discounts and food markets [24] aimed at alleviating common factors associated with food insecurity such as the financial constraints discussed. However, some of their suggestions are unique, and involved building relationships and connections to learning about food practices from Elders and other knowledge holders. These findings suggest that although there are barriers in terms of financial capacity as post-secondary students, social and cultural supports are also necessary to build dietary and cultural diversity for Indigenous students living away from supportive food environments in their home communities.

Themes among the student participants in this study generally reflected individual and interpersonal influences on food and nutrition practices (see Figure 1). The types of interventions at these levels of the SEM aimed at address food insecurity tend to be most commonly “quick wins” such as financial coaching, food sharing, and institution-level interventions such as on-campus food pantries [39] (p. 7). The focus group discussion, however, expanded on these perspectives, concentrating on food environments more so at organizational and community levels. Focus group participants discussed potential factors limiting student awareness of resources on and off-campus, such as accessing emergency food services such as food banks and food pantries in the city. ISC staff assisted Indigenous students in accessing resources on campus such as the campus food bank and their informal food pantry. Within Canada, there are limited data on whether students, in particular Indigenous students, are accessing these resources and whether or not these strategies are effective [39]. In the province of Manitoba, few students reported using food banks as a coping strategy to deal with food insecurity [5]. Less than 1% of University of Saskatchewan students reported accessing the campus food bank in the previous 12 months [16]. In Ontario, students expressed feelings of stigma and shame when accessing the campus food bank [3,46]. Overall, these findings are similar to the results in the current study, indicating that the campus food bank is not reaching all students and there is limited knowledge about Indigenous student access and their unique food needs.

Compromised food choices and anxiety related to lack of control over food could have negative effects on psychological and social well-being [3,4]. Services food banks and pantries provide may be viewed as individualistic compared to programming and supports provided on campus through the ISC and within the community at seasonal and other feasts or events. These social and cultural supports were identified by all participants as major themes in this study. Interestingly, however, these wider organizational and community supports were mentioned by the students in their recommendations. They were not discussed as part of their personal or individual experiences as Indigenous post-secondary students. An Australian study discussed the importance of Aboriginal Support Centres for supporting students on a variety of levels, aimed at both physical and mental wellness [47]. Creating positive and supportive relationships among Indigenous students, their peers and instructors is known to encourage academic successes [40]. Authors from another study that looked at the role of the former Aboriginal Student Centre at the University of Guelph, found that the Centre, its staff and volunteers build a sense of community, fosters knowledge and enhancement of identity for Indigenous students [48].

5. Conclusions

Attending university often involves a critical transition from living at home to becoming more independent. Circumstances of food insecurity among university students across Canada have been identified as a significant barrier; however, the perspectives of Indigenous students have been overlooked. One of the main strengths of this study is that it is the first to solely explore these complex and changing food environments that exist for Indigenous students using qualitative methods. By conducting face-to-face interviews with self-identified Indigenous students and focus groups with Indigenous community members and service providers, the research truly illustrated the experiences of Indigenous students, in their own words. Their perspectives and recommendations, combined with the insights of university representatives and advocates provide insight into the unique barriers Indigenous students face alongside the challenges that continue to exist for Indigenous youth in accessing post-secondary education within Canada [49].

There are some valuable themes and recommendations that arose from this exploratory investigation. Students recommended, for example, that the ISC could create more awareness about events and other supportive resources for Indigenous students to socialize and learn about food. Participants provided suggestions for adding to events such as introducing an annual campus Pow Wow event, cooking classes and Elder workshops. To advocate for greater awareness within institutions such as universities at an organizational and even policy level, Indigenous students need to be supported by building connection and relationship networks on- and off-campus. Several student participants found out about the ISC only well into the upper years, and these added supports and resources might have been most useful to them as new students. The University of Guelph has established an Indigenous Initiatives Strategic Taskforce in support of enhancing recognition and respect for Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing (49). A newly released report on Indigenous student support that provides a series of recommendations to enhance personal and cultural development. Recommendations include establishing full-time Elder roles, lunch and learn programs, and ceremonial space on campus.

Community service providers discussed increasing awareness and formally evaluating emergency food resources that currently exist for Indigenous students. By increasing awareness of these services and the dimensions and diversity of student food insecurity, issues of stigma for Indigenous students and others could potentially be alleviated. Service providers had limited knowledge of the needs of Indigenous students on campus and in the wider community, interestingly mirroring the lack of experience Indigenous students had with off campus resources and Indigenous community supports outside of their small networks of friends and peers. These findings suggest a gap in food service provision for Indigenous students, particularly those living off-campus.

Food-insecure students are at increased risk of adverse health and academic outcomes, which may impact student retention and health behaviours beyond university [4]. If so, the impact would not be limited to the individual. Additional research is required utilizing multiple methodologies to more accurately assess rates and circumstances of food insecurity among Indigenous university students and more clearly illustrate these unique dimensions both on and off-campus. Utilizing survey methods combined with participatory research methodologies would assist in identifying Indigenous student concerns across a wider range of social and ecological environments. At the same time, it is important to consider how the often-narrow concept of food insecurity is discussed and measured, and dietary practices utilizing a deficit-based lens. Food insecurity is not exclusively related to the financial inability to purchase food or the utilization of food related to its nutrient contributions and physical health benefits [1]; the mental, emotional and spiritual benefits that food contributes towards the wellness of individuals and communities need to be considered too. Future intervention studies also need to evaluate strategies aimed at supporting students to more accurately depict the consequences of barriers faced and moving beyond food security to realizing food rights or sovereignty within diverse food environments [4]. Communities and institutions are unique in their student demographics, resources, and financial and social supports, and thus can provide results relevant to support the needs and overall wellness of Indigenous students across academic institutions within Canada.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su131810268/s1, Table S1: Semi-structured interview guide questions (n = 8); Table S2: Focus group questions guide (n = 4).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T.N., K.A. and C.W.; methodology, H.T.N. and H.W.; analysis, H.W. and H.T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W.; writing—review and editing, H.T.N., H.W., K.A., C.W. and D.E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the University of Guelph (protocol 17-09-033).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the support of campus partners, and research assistants Melanie Aguiar, Kristine Keon, Nour Musharbash and Sivanah Mungal. We are grateful to the students, campus staff and community members who were willing to share their time and experiences as participants in this study. The research was conducted as the first author’s graduate program and is published in its complete form as her MSc thesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Silverthorn, D. Hungry for Knowledge: Assessing the Prevalence of Student Food Insecurity on Five Canadian Campuses. 2016. Toronto: Meal Exchange. Available online: http://cpcml.ca/publications2016/161027-Hungry_for_Knowledge.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Alternative Federal Budget 2015: Delivering the Good. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2015. Available online: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/alternative-federal-budget-2015 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Hattangadi, N.; Vogel, E.; Carroll, L.J.; Côté, P. “Everybody I Know Is Always Hungry…But Nobody Asks Why”: University Students, Food Insecurity and Mental Health. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Zein, A.; Shelnutt, K.P.; Colby, S.; Vilaro, M.J.; Zhou, W.; Greene, G.; Olfert, M.D.; Riggsbee, K.; Morrell, J.S.; Mathews, A.E. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among U.S. college students: A multi-institutional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entz, M.; Slater, J.; Aurélie, A. Student food insecurity at the University of Manitoba. Can. Food Stud. 2017, 4, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El Zein, A.; Colby, S.; Zhou, W.; Shelnutt, K.; Greene, G.; Horacek, T.; Olfert, M.; Mathews, A. Food insecurity Is associated with increased risk of obesity in US college students. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffino, J.; Spoor, S.; Drach, R.; Hormes, J. Food insecurity among graduate students: Prevalence and association with depression, anxiety and stress. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, L.; Mathews, M.; Bowley, C.; Roebothan, B. Determining student food insecurity at Memorial University of Newfoundland. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2018, 80, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, S.; Laban, S.; Primeau, C. Assessing the Prevalence of Food Insecurity at the University of Guelph. 2020. Community Engaged Scholarship Institute. Available online: https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/handle/10214/2501 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Whatnall, M.; Hutchesson, M.; Patterson, A. Predictors of food insecurity among Australian university students: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murray, S.; Peterson, C.; Primo, C.; Elliott, C.; Otlowski, M.; Auckland, S.; Kent, K. Prevalence of food insecurity and satisfaction with on-campus food choices among Australian university students. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, D.; Ramsey, R.; Ong, K.W. Food insecurity: Is it an issue among tertiary students? High. Educ. 2014, 67, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meldrum, L.A.; Willows, N.D. Food insecurity in university students receiving financial aid. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2006, 67, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micevski, D.A.; Thornton, L.E.; Brockington, S. Food insecurity of tertiary students. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 71, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazmi, A.; Martinez, S.; Byrd, A.; Robinson, D.; Bianco, S.; Maguire, J.; Rashida, M.; Crutchfeild Condron, K.; Ritchie, L. A systematic review of food insecurity among US students in higher education. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2018, 14, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olauson, C.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Vatanparast, H.; Hanoski, R. Student food insecurity: Examining barriers to higher education at the University of Saskatchewan. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2018, 13, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.; Mitchell, A. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2017–2018. Toronto: Research to Identify Policy Options to Reduce Food Insecurity, 2020, Proof. Available online: http://proof.utoronto.ca (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Mikkonen, J.; Raphael, D. Canadians’ health is mostly shaped by social determinants. CCPA Monit. 2010, 17, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Hattangadi, N.; Vogel, E.; Carroll, L.J.; Côté, P. Is food insecurity associated with psychological distress in undergraduate university students? A cross sectional study. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2019, 16, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.; Beaton, G. Household food insecurity and hunger among families using food. Can. J. Public Health 1999, 90, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innis, J.; Bishop, M.; Boloudakis, S. Food insecurity and community college students. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2019, 44, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Security Policy Brief. 2006. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/faoitaly/documents/pdf/pdf_Food_Security_Cocept_Note.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Eicher-Miller, H.A.; Mason, A.C.; Weaver, C.M.; McCabe, G.P.; Boushey, C.J. Food insecurity is associated with iron deficiency anemia in US. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1358–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farahbakhsh, J.; Hanbazaza, M.; Ball, G.; Farmer, A.; Maximova, K.; Willows, N. Food insecure student clients of a university–based food bank have compromised health, dietary intake and academic quality. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 74, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/201216/dq201216d-eng.htm (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Chan, L.; Batal, M.; Sadik, T.; Tikhonov, C.; Schwartz, H.; Fediuk, K.; Ing, A.; Marushka, K.L.; Barwin, L.; Berti, P.; et al. Final Report for Eight Assembly of First Nations Regions: Draft Comprehensive Technical Report. 2019. Fnfnes. Available online: http://www.fnfnes.ca/docs/FNFNES_draft_technical_report_Nov_2__2019.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Richmond, C.; Steckley, M.; Neufeld, H.; Kerr, R.B.; Wilson, K.; Dokis, B. First Nations Food Environments: Exploring the Role of Place, Income, and Social Connection. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 48, nzaa108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Murphy, B.; Deierlein, A.; Parekh, N.; Bihuniak, J. Food insecurity and associated demographics, academic and health factors among undergraduate students at a large urban university. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huet, C.; Rosol, R.; Egeland, G.M. The prevalence of food insecurity is high and the diet quality poor in Inuit Communities. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, H.; Richmond, C. The Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre. Impacts of place and Social Spaces on Traditional Food Systems in Southwestern Ontario. Int. J. Indig. Health 2017, 12, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- USAI Research Framework. Ontario Federation of Indian Friendship Centres, 2012. Available online: http://ofifc.org/sites/default/files/docs/USAI%20Research%20Framework%20Booklet%202012.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Brant Castellano, M. Ethics of Aboriginal research. J. Aborig. Health 2004, 1, 98–114. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burke, N.J.; Joseph, G.; Pasick, R.J.; Barker, J.C. Theorizing social context: Rethinking behavioral theory. Health Educ. Behav. 2009, 36, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kilanowski, J. Breadth of the socio-ecological model. J. Agromedicine 2017, 22, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberge Gaudin, V.; Receveur, O.; Walz, L.; Girard, F.; Potvin, L. A mixed methods inquiry into the determinants of traditional food consumption among three Cree communities of Eeyou Istchee from an ecological perspective. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2014, 73, 24918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amore, L.; Buchthal, O.V.; Banna, J.C. Identifying perceived barriers and enablers of healthy eating in college students in Hawai’i: A qualitative study using focus groups. BMC Nutr. 2019, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruening, M.; Argo, K.; Payne-Sturges, D.; Laska, M.N. The Struggle Is Real: A Systematic Review of Food Insecurity on Postsecondary Education Campuses. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1767–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogari, G.; Velez-Argumedo, C.; Gómez, M.I.; Mora, C. College Students and Eating Habits: A Study Using an Ecological Model for Healthy Behavior. Nutrients 2018, 23, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilson, C.K.; Matthews, J.I.; Seabrook, J.A.; Dworatzek, P.D.N. Self reported food skills of university students. Appetite 2017, 108, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, R.; Yassa, B.; Parker, H.; O’Connor, H.; Allman-Farinelli, M. University students’ on-campus food purchasing behaviors, preferences, and opinions on food availability. Nutrition 2017, 37, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deliens, T.; Clarys, P.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B. Determinants of eating behaviour in university students: A qualitative study using focus group discussions. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallop, C.J.; Bastien, N. Supporting success: Aboriginal students higher education. Can. J. High. Educ. 2016, 46, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiraian, D.; Sobal, J. Dating and eating. How university students select eating settings. Appetite 2009, 52, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, M.; Meyer, S.; Perlman, C.; Kirkpatrick, S. Experiences of Food Insecurity among Undergraduate Students: “You Can’t Starve Yourself Through School”. Can. J. High. Educ./Rev. Can. D’enseignement Supérieur 2018, 48, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, R.; Grote, E.; Rochecouste, J.; Dann, T. Indigenous student perspectives on support and impediments at university. Aust. J. Indig. Educ. 2016, 45, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.L.; Varghese, J. Role, impacts and implications of dedicated Aboriginal student space at a Canadian university. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2016, 53, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Guelph. Indigenous Initiatives Summary Report 2021. Available online: https://indigenous.uoguelph.ca/system/files/Indigenous-Initiatives-Strategy-Summary-Report.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).