Abstract

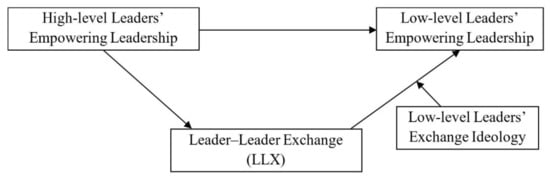

This study suggests a comprehensive social learning model of empowering leadership by focusing on the antecedents and processes of empowering leadership. Data were obtained from subordinate–supervisor dyads from the South Korean Army. The results support the social learning of empowering leadership. Specifically, the empowering leadership of high-level leaders facilitates that of low-level leaders, and this relationship is mediated by leader-leader exchange (LLX). Additionally, the results confirm the existence of a moderated mediation relationship among the constructs of interest; that is, the exchange ideology of low-level leaders moderates the relationship between LLX and their empowering leadership, such that the relationship is stronger when the exchange ideology is weak rather than strong. Thus, a weak exchange ideology strengthens the indirect effects of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders on that of low-level leaders through LLX. Theoretical and practical implications are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Leadership is one of the most crucial contextual factors to enhance organizational effectiveness [1,2,3]. Among the various leadership styles, empowering leadership has received considerable attention in the field of leadership [4,5]. Although the concept of empowering leadership has been in line with a stream of supportive leadership [6], participative leadership [7], and delegating behaviors covered in situational leadership theory [8], this attention is based on the belief that employees who are given more opportunities for self-direction and greater autonomy achieve higher performances. Empowering leadership refers to the actions of a leader that accompany the process of sharing their power or more responsibilities and autonomy with members [9,10]. Considerable research has demonstrated that empowering leadership increases organizational commitment [1,11], job satisfaction [12,13], employee creativity [14,15,16], and team performance [17].

Although many empirical studies have documented a significant positive relationship between empowering leadership and desirable work delivery by members, there has been a lack of research on the antecedents and processes of such leadership. To expand our knowledge, comprehending the factors that promote empowering behaviors in a leader that would bring positive outcomes to an organization and understanding of the processes thereof are essential. Thus, this study investigates the antecedents of empowering leadership vis-à-vis the social learning theory [18], which posits that individuals learn and imitate behaviors when forming their own attitudes and behaviors. Specifically, this study examines the effects of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders (leader’s leader or leader’s supervisor) on that of low-level leaders.

In the workplace, leaders are “linking-pins” connecting their subordinates and supervisors [19,20]. Thus, it is necessary to investigate the impacts of high-level leaders’ understanding of the empowering behaviors of low-level leaders because such leaders are their direct supervisors, and this can affect the behaviors and perceptions of the former. Moreover, leaders not only form exchange relationships with their subordinates (i.e., leader–member exchange: LMX) but also form important relationships with their direct supervisors through leader-leader exchange (LLX), which serves as a crucial link within their network [20]. Accordingly, in social learning processes relating to empowering leadership, the empowering leadership behaviors of low-level leaders can be influenced by the quality of the exchange relationship that they have with their own supervisors (i.e., LLX). To explore the social learning processes of empowering leadership more closely, this study examines the mediating role of LLX in the relationship between empowering leadership of high-level leaders and that of low-level leaders.

Finally, this study further investigates the moderating effects of the exchange ideology of low-level leaders in the relationship between LLX and empowering leadership. As an individual factor considered in the social learning processes of empowering leadership, exchange ideology refers to individuals’ belief system that the degree of their work efforts is dependent on the treatment by the organization [21]. The extent of an intention to reciprocate favorable treatments by the subject of the exchange in interpersonal relationships depends on the norm on reciprocity held by individuals [22,23]. Thus, this study examines whether the exchange ideology of low-level leaders moderates the relationship between LLX and their empowering leadership.

In summary, to advance our understanding of empowering leadership in work settings, this study had three main objectives: First, this study examined the influence of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders on that of low-level leaders. Second, this study investigated the mediating effect of LLX in the social learning process of empowering leadership between high- and low-level leaders. Third, using moderated mediation, this study investigated the moderating roles of exchange ideology in the relationship between LLX and the empowering leadership of low-level leaders.

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. Social Learning of Empowering Leadership

Empowering leadership as a process of sharing power and granting autonomy to employees includes five key dimensions such as leading by example, coaching, informing, participative decision-making, and showing concern [24]. Many studies have suggested that empowering leadership is an important driver toward delivering organizational efficacy and desirable outcome variables by members [4,17,25,26]. For example, Ahearne et al. [4] showed that empowering leadership facilitated salespersons’ adaptability and increased their performance and service satisfaction. Srivastava et al. [17] demonstrated the positive effect of empowering leadership on knowledge sharing, team efficacy, and team performance. Many other researchers also suggested the positive relationships between empowering leadership and subordinates’ outcomes, and these include increased work engagement [27], organizational citizenship behavior [5], leader effectiveness and affective commitment through LMX [1], team creativity [25], core task proficiency and proactive behaviors [28], safety behaviors [29], and employee well-being [30]. However, there is a lack of research on the antecedents of empowering leadership. Indeed, most of the empowering leadership literature has focused on documenting the positive outcomes of empowering leadership and has devoted minimal attention to understanding what factors can predict and lead to empowering leadership behaviors.

One of the main issues in the leadership literature relates to the following question: “How can leaders learn or develop their leadership skills?” Many researchers have suggested that the leader plays a decisive role in shaping the job-related attitudes and behaviors of members in the work environment [31,32]. Accordingly, high-level leaders can have a great influence on the attitudes and behaviors of low-level leaders through social learning [32]. Based on the social learning theory [18], individuals learn and imitates the behaviors of others who they consider important when shaping their attitudes and behaviors [33]. Consequently, by imitating the desirable behaviors of their leader in the social learning process, leaders can form and develop their own leadership pattern [34] because a desirable and attractive leader can be an excellent role model whose behaviors can be followed by others [33]. Therefore, by learning or imitating the empowering behaviors of their superiors, leaders could increase the possibility of fostering their own empowering leadership behaviors [34]. Furthermore, the leadership qualities of an upper-level leader could affect the perceptive and behavioral processes of lower-level leaders and, thus, their behaviors [35]. In a similar context, Schaubroeck et al. [34] suggested that from the social learning theory perspective [18], the ethical leadership of lower-level leaders was positively correlated with that of their upper-level leaders. They also found that ethical culture and climate had direct and indirect influences on ethical behaviors transmitted across multiple levels of an organizational hierarchy. Similarly, Schein [36] suggested that “shared cultural elements” that were similar to organizational climates could be observable and were referred to as surface-level cultural aspects. Schein [36] insisted that leaders at hierarchical levels could influence the lower levels of an organization’s culture, such as behavioral norms, policies, and standards. Based on the above-mentioned discussions, this study hypothesizes that there is a positive relationship between empowering leadership of the leaders at two levels.

Hypothesis 1.

The empowering leadership of high-level leaders is positively related to that of low-level leaders.

2.2. LLX and Empowering Leadership

In an organizational setting, leaders not only form exchange relationships with their subordinates (i.e., LMX) but also form important relationships with their superiors within the organizational network (i.e., LLX) [20]. Leader–member exchange (LMX) theory posited that leaders form different exchange relationships with their subordinates and that the quality of this relationship influences their work-related attitudes and behaviors [37]. Based on social exchange theory [38], LMX theory explains the development of dyadic linkages between a supervisor and an employee and the relationships between leadership processes and outcomes. Thus, in the social learning processes of empowering leadership, the empowering behaviors of low-level leaders can be influenced by the quality of the exchange relationship that leaders have with their own supervisor (i.e., LLX). Although studies on the relationship between empowering leadership and relations with exchange partners, such as LMX or LLX, are limited, several previous studies have revealed a positive relationship between the consultation of a leader and LMX [39]. Moreover, many researchers have demonstrated a significant effect of delegation on the relationship between two exchange partners [39,40]. Thus, the empowering leadership of high-level leaders can be associated with a higher sense of the LLX of low-level leaders in this study.

Additionally, a higher quality of LLX between leaders and their own supervisors is also likely to enhance empowering behaviors toward their own subordinates because LLX allows leaders to retain greater autonomy, position, or resources [20]. Indeed, leaders with higher levels of LLX can give subordinates more material and social support in their work [41], which can lead subordinates to feel that they are more capable of performing tasks and have greater autonomy in fulfilling duties. Accordingly, high LLX quality would be positively related to low-level leaders’ empowering leadership toward subordinates. Therefore, this study hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 2.

Leader-leader exchange mediates the relationship between the empowering relationship of high-level leaders and that of low-level leaders.

2.3. Moderating Role of Exchange Ideology

Exchange ideology entails individuals’ belief that it is appropriate and beneficial to base the extent of their efforts put into work on how well they are treated by their organization [38]. According to social exchange theory [42], employees’ exchange ideology deals with their application of the reciprocity norm to relationships with their organization. A person with a strong exchange ideology can be regarded as a more calculative and self-focused person [22,23,43]. Such persons have more interest in what they receive than on what they give compared with individuals with a weak exchange ideology [21,22]. Compared to those with a weak exchange ideology, individuals with a strong exchange ideology have a more intense tendency to perceive fair exchange situations as being less fair than they are [22]. Persons with a weak exchange ideology can be characterized by their being more open-minded and benevolent than those with a strong exchange ideology in their exchange relationships [23,44]. Thus, the exchange ideology of low-level leaders can play an important role in their relationships with their leaders and in fostering empowering leadership.

Specifically, this study predicts that there would be a stronger positive relationship between LLX and empowering leadership in leaders with a strong exchange ideology than those with a weak one. Given that individuals with a strong exchange ideology are more likely to be self-centered and calculative, it is less likely that such leaders would take certain actions, such as empowering leadership, that would engender outcomes that are beneficial to the organization and display strong commitment. Moreover, leaders with a strong exchange ideology may respond to negative types of information more sensitively and consider the same events in an interactive relationship more negatively than those with a weak exchange ideology [23]. This characteristic may further suppress the positive effects of support from their exchange partner. Thus, leaders with a strong exchange ideology may exhibit less positive relationships between LLX and empowering leadership. Conversely, leaders with a weak exchange ideology may amplify the effects of the relationship with their supervisors on empowering leadership because they tend to be more open and generous in exchange relationships [23,44]. Therefore, this study hypothesizes as follows:

Hypothesis 3-a.

Exchange ideology moderates the relationship between leader-leader exchange and the empowering leadership of low-level leaders, such that the relationship is stronger when exchange ideology is weak rather than strong.

Assuming that the exchange ideology of low-level leaders moderates the association between LLX and empowering leadership, it conditionally affects the strength of the indirect relationship between the empowering leadership of high- and low-level leaders. As this study predicted a strong (weak) relationship between LLX and the empowering leadership of low-level leaders when their exchange ideology was weak (strong), it expected the following:

Hypothesis 3-b.

The exchange ideology of low-level leaders moderates the positive and indirect effect of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders on that of low-level leaders through leader-leader exchange. Specifically, the mediated relationship is stronger when exchange ideology is weak than when it is strong.

Figure 1 presents our hypothesized model.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model.

3. Method

3.1. Sample

In the present study, the participants included platoon leaders (supervisors) and members (subordinates) of the South Korean Army. With the unit commander’s permission, the survey was conducted after work hours. After getting permission to collect data from six army divisions, thirty-two battalions were randomly selected by each division’s training staff officers after considering the units’ training and mission schedules. The platoon leaders who were willing to participate in the supervisor survey voluntarily gathered in a separate room from the platoon members who were willing to partake in the subordinate survey. This separation was done to prevent any feelings of pressure that could ensue in a military setting. The questionnaires were distributed to the participants using a unit code system that allowed the distribution of the questionnaires to the right individuals and to match up the supervisor–subordinates dyads without requiring a list of names. Code numbers were used simply to match up the responses for the dyads. Prior to the survey, it was announced to all the participants that participation in the survey was voluntary, and that privacy was protected. The participants were provided with cookies and snacks worth less than US$ 2 per participant. After collecting both sets of surveys, the supervisor and subordinate data were matched up.

Three-hundred and sixty questionnaires were distributed to 360 subordinates (platoon members) and their 360 direct supervisors (platoon leader: low-level leaders). Two-hundred and sixty-nine subordinate questionnaires (74%) and 260 low-level leader questionnaires (72.2%) were returned. After excluding the incomplete and unmatched questionnaires (i.e., those that did not have a reply from either the platoon member or the leader), 207 supervisor–subordinate pairs were used for the analyses in this study.

Notably, 99.5% of the subordinates were male, and the average age was 23.1 years (SD = 1.61). All had graduated at least high school, 20.7% held bachelor degrees, and 21.7% had masters or doctoral degrees. Furthermore, 98.6% of the subordinates were single and the average job tenure with their low-level leader was 1.0 year (SD = 0.73). For supervisors (low-level leaders), 97.6% were male, the average age was 28.0 years (SD = 4.90), and the average job tenure with their supervisor (high-level leaders) was 0.9 years (SE = 0.59). Additionally, 87.6% of all the supervisors held bachelor degrees and 16.5% had masters or doctoral degrees.

3.2. Measures

The English language questionnaires were translated into Korean using the conventional method of forward and backward translation [45] by bilingual (English and Korean) scholars. With the exception of the empowering leadership of low-level leaders, which was subordinate-rated, data on the other variables were rated by supervisors (low-level leaders). Specifically, the low-level leaders evaluated the empowering leadership of their own direct supervisors (high-level leaders), as well as their own perception of LLX and exchange ideology. Study variables were measured by a cross-sectional study design in which all of the variables were measured at a single point in time. These were assessed using multi-item scales used in previous research with good internal consistency. All the items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Empowering leadership. Empowering leadership was measured using Ahearne et al.’s [4] 12-item scale. Low-level leaders (platoon leaders) evaluated the leadership of high-level leaders (company commanders), while subordinates evaluated the empowering leadership of low-level leaders. Thus, the empowering leadership of low- and high-level leaders was evaluated by their respective direct subordinates. A sample item reads: “My supervisor makes many decisions together with me.”

LLX. To measure the upward relationship (i.e., LLX) of low-level leaders with their superiors, this study used the adaptation of seven items with word changes from the LMX7 measure [46], as suggested by Liden, Wayne, and Stillwell [47] and Bauer and Green [48] (e.g., Chen et al., Tangirala et al.) [20,41]. A sample item is: “My supervisor understands my problems and needs well enough.”

Exchange ideology. To measure employees’ beliefs that it is appropriate to help with the goal achievement of the organization in exchange of receiving favorable treatments, this study used the eight items from the employee exchange ideology questionnaire [42]. A sample item states: “An employee’s work effort should depend partly on how well the organization deals with his or her desires and concerns.”

Control variables. This study conducted a regression analysis with various control variables, such as age, education, and tenure with one’s direct supervisor. Age was measured in years. In terms of education, graduating from high school was coded as 1, community college as 2, undergraduate as 3, and more than undergraduate as 4. Tenure with one’s direct supervisor was measured according to the number of months respondents had worked with their current supervisor.

3.3. Data Analysis

Hierarchical regression analysis was used to verify the hypothetical relationships. Moreover, the moderated mediation hypothesis in the studied model was analyzed using the statistical methods and SPSS syntax suggested by Preacher et al. [49]. The strength of conditional indirect effects was verified using bias correction and bootstrapping methods [50]. To alleviate the potential multicollinearity problem in the verification of the moderating effects, LLX and exchange ideology were mean-centered before the generation of the second-degree term. The pattern of interactions was plotted following Aiken and West [51].

4. Results

Prior to testing our hypotheses, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) using the AMOS software package to confirm the discriminant validity among the study variables. The results showed that the proposed four-factor model fitted the data well (χ2 (98) = 215.86, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.07), and was significantly better than a three-factor model combining high-level empowering leadership and LLX (χ2 (101) = 265.17, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.09); a two-factor model combining high-level empowering leadership, LLX, and exchange ideology of low-level leaders (χ2 (103) = 455.37, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.86, TLI = 0.84, RMSEA = 0.13); and a one-factor model combining all variables into one factor (χ2 (104) = 860.67, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.71, TLI = 0.66, RMSEA = 0.19).

Table 1 presented the Cronbach’s alpha values and correlation coefficients among variables. None of the correlations were above the 0.90 threshold suggested by Hair et al. [52]. The reliabilities of all measurements were higher than the 0.70 standard generally considered to be acceptable for research purposes [53].

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Hypothesis 1 predicted a positive relationship between the empowering leadership of low-level leaders and that of high-level leaders. In Table 2, Model B2 showed a significant positive effect of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders on that of low-level leaders (β = 0.23, p ≤ 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression of mediation results of LLX between high-level leaders’ empowering leadership and that of low-level leaders.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that LLX would mediate the relationship between the empowering leadership of high- and low-level leaders. In Table 2, Model A2 showed a significant effect of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders’ on LLX (β = 0.87, p ≤ 0.001). As shown in Model B3, LLX also showed a significant effect on the empowering leadership of low-level leaders. However, the positive effect of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders on that of low-level leaders in Model B2 (β = 0.23, p ≤ 0.001) was reduced to a non-significant effect in Model B4 (β = −0.09, n.s.) when LLX was simultaneously inputted. The positive effect of LLX on the empowering leadership of low-level leaders was still significant in Model B4 (β = 0.37, p ≤ 0.01). The F change was significant (ΔF = 7.05, p < 0.01), and the R2 change was substantial (ΔR2 = 0.03). Consequently, according to Baron and Kenny’s [54] mediation logic, LLX served as a full mediator of the relationship between the empowering leadership of high- and low-level leaders.

As shown in Table 3, Sobel’s test and bootstrap methods were also conducted to ensure the indirect effect of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders on that of low-level leaders through LLX. In Sobel’s test, the mediating effect of LLX was significant (p < 0.01). In the bootstrapping results, the 99% confidence interval did not include zero (ranging from 0.01 to 0.56), and the mediating effect of LLX was significant in the 99% confidence interval. In short, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Table 3.

Indirect effect of high-level leaders’ empowering leadership on that of low-level leaders through LLX.

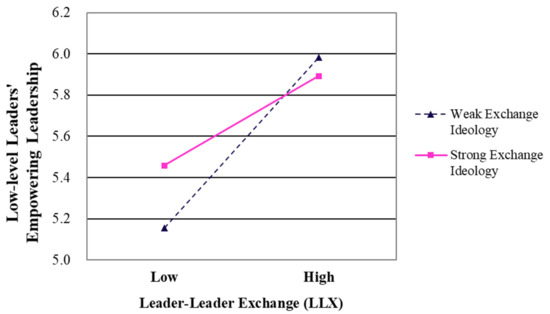

Hypothesis 3-a predicted a moderating role of exchange ideology in the relationship between LLX and the empowering leadership of low-level leaders such that the positive relationship would be stronger when exchange ideology was low rather than high. In Model 4 of Table 4, the interaction term of LLX and exchange ideology (LLX × EXID) showed a significant effect on the empowering leadership of low-level leaders (β = −0.14, p ≤ 0.05), and the interaction term showed a significant incremental variance (ΔF = 4.29, p < 0.05). To comprehensively explore this interaction effect, it was plotted using the Aiken and West [51]’s procedure. As illustrated in Figure 2, the positive relationship between LLX and the empowering leadership of low-level leaders was stronger when the leaders’ exchange ideology was low than when it was high. These results provide support for Hypothesis 3-a.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regression Results on Low-level Leaders’ Empowering Leadership.

Figure 2.

Moderating Effect of Exchange Ideology.

Hypothesis 3-b proposed a moderated mediation effect of exchange ideology such that the exchange ideology of low-level leaders would conditionally affect the strength of the indirect effect of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders on that of the former through LLX. The SPSS macro developed by Preacher et al. [49] was utilized to test this moderated mediation hypothesis. The bootstrap results on the moderated mediation effect are reported in Table 5. Consistent with Hypothesis 3-b, the indirect effect of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders on that of low-level leaders via LLX was conditional on the level of exchange ideology. The indirect effect on the empowering leadership of low-level leaders was stronger (0.37) and more significant (99% confidence interval ranging from 0.10 to 0.69, and not crossing zero) when the exchange ideology was weak. Therefore, Hypothesis 3-b was also supported.

Table 5.

Conditional indirect effects on low-level leaders’ empowering leadership across LLX.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrates the social learning process of empowering leadership, including the antecedents and moderators of empowering leadership. The findings of H1 supported that low-level leaders learn their empowering leadership from their direct supervisors. The support for H2 verified the mediation effect of LLX in the social learning process of empowering leadership between high- and low-level leaders. The significant results for H3–a and H3–b show that exchange ideology plays a moderating role in the social learning process of empowering leadership through LLX.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings make significant contributions to the research on empowering leadership in the following ways: First, this study sheds light on the antecedents of empowering leadership, thereby supplementing the literature. This study tested the effects of relational and individual factors on empowering leadership among low-level leaders. The results suggest that LLX and exchange ideology can all play an important role in influencing empowering leadership. LLX served as a major mechanism for the empowering leadership of high-level leaders to influence the empowering behavior of low-level leaders. Ilies et al. [55] argued that LMX (or LLX) explained the development of dyadic linkages and the relationships between leadership processes and behavioral outcomes. Cheong et al. [56] pointed out that there is lack of studies focused on examining antecedents of empowering leadership. Thus, this study filled the gap of prior studies on empowering leadership by suggesting that LLX plays an important role as a relational antecedent factor of empowering leadership. Moreover, this study demonstrated the role of exchange ideology, which is a major individual characteristic in social exchange theory, in the social learning process of empowering leadership. Many researchers have suggested that the personal characteristics of leaders play a critical role in predicting their leadership behaviors [57,58]. On the same line, this study suggested that exchange ideology of leaders can be a major influencing factor in determining their empowering behavior.

Second, by applying the social learning theory [18], this study tests whether the empowering leadership of high-level leaders can be an antecedent of that of low-level leaders. Although some researchers have suggested that low-level leaders learn their empowering leadership from their supervisors’ leadership styles [32], there has been little attention paid to empowering leadership. For example, Schaubroeck et al. [34] suggested that junior supervisors learned ethical leadership from their senior supervisors. Byun et al. [59] also provided evidence that ethical leadership of high-level leaders trickles down to low-level leaders, and results in desirable employee work outcomes. By incorporating this previous leadership learning process in a social learning theory perspective, this study provides additional empirical evidence that the empowering leadership of high-level leaders facilitates the formation of the empowering leadership of their direct subordinates.

Third, this study tested a moderated mediation chain of empowering leadership learning that was more complicated than previously investigated. Specifically, this study tested the conditional indirect effects of the empowering leadership of high-level leaders on that of low-level leaders through LLX, as influenced by the differing levels of exchange ideology. These results showed that the mediation effects of LLX in the social learning process of empowering leadership could be maximized under conditions of low exchange ideology, thereby providing greater insight into the specific processes affecting trickle-down effects.

5.2. Practical Implications

In today’s highly competitive business environment, organizations should fully utilize employees’ potential and motivation [60]. Empowering leadership is one of the useful ways to make employees more adaptive toward increasing organizational flexibility because empowered members could increase organizational performance by enabling and encouraging them in their work roles [4,61]. However, many organizations have focused mainly on low-level leaders’ training for increasing empowering skills, rather than on creating an organizational context for the successful implementation of an empowering culture. This study demonstrates that the empowering leadership of high-level leaders plays an important role in the enhancement of that of lower-level leaders.

This study also suggests that LLX is a critical relational factor that facilitates empowering leadership. Leaders who maintain good exchange relationships with supervisors are more willing to learn their supervisors’ desirable leadership styles and empowering leadership abilities. Exchange ideology can be a key individual factor that affects the social learning process of empowering leadership. Leaders with low exchange ideology can learn their supervisors’ empowering leadership styles more easily. Lastly, this study provides useful practical implications relating to the trickle-down effects of empowering leadership. Namely, the empowering behaviors of high-level leaders can positively affect the empowering leadership of low-level leaders, which may consequently increase their subordinates’ positive outcomes. In conclusion, empowering behaviors could have a synergistic effect across leadership levels. Thus, top managers and high-level leaders should focus on creating a more empowering environment through training that strengthens leadership and by leading by example. In addition, the organization should strive to form a horizontal organizational culture to promote empowering leadership because hierarchical culture, which has the most control over its employees [62], can undermine leaders’ empowering behaviors.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Future research should further explore the trickle-down effects of empowering leadership through various organizations. Furthermore, more research is needed to determine the potential factors that could strengthen or weaken this effect. This study utilized a cross-sectional analysis that collects all data at one point in time, which posed constraints for inferring causality and produced the possibility of common method bias [63]. To verify this, we employed the partial-correlation adjustment with the marker variable by Lindell and Whitney [64]. It was confirmed that there was no significant difference in the correlation values before and after including the marker variable, which results in no common method bias in the data. Nevertheless, longitudinal studies may provide deeper insight into the relationships among the variables in future research. This study was also conducted with data obtained from South Korea. Though this can facilitate the understanding of organizational dynamics across nations, future studies in other national settings would help to verify and extend these results. Moreover, in accordance with previous studies, this study only measured the perceptions of responses that could be subjective. Future research may select more objective measures to avoid this potential problem. Based on the results of this study, future research can further open the black box of empowering leadership by studying its additional potential antecedents and processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B. and S.L.; methodology, G.B.; software, G.B.; validation, G.B. and S.L.; formal analysis, G.B.; investigation, G.B.; resources, G.B.; data curation, G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.B.; writing—review and editing, S.L.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, S.L., Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hassan, S.; Mahsud, R.; Yukl, G.; Prussia, G.E. Ethical and empowering leadership and leader effectiveness. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kanfer, R. Toward a systems theory of motivated behavior in work teams. Res. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 223–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogdill, R.M. Handbook of Leadership: A Survey of the Literature; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ahearne, M.; Mathieu, J.; Rapp, A. To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Dijke, M.; De Cremer, D.; Mayer, D.M.; Van Quaquebeke, N. When does procedural fairness promote organizational citizenship behavior? Integrating empowering leadership types in relational justice models. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2012, 117, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, D.G.; Seashore, S.E. Predicting organizational effectiveness with a four-factor theory of leadership. Adm. Sci. Q. 1966, 11, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Schweiger, D.M. Participation in decision-making: One more look. Res. Organ. Behav. 1979, 1, 265–339. [Google Scholar]

- Hersey, P.; Blanchard, K.H.; Natemeyer, W.E. Situational leadership, perception, and the impact of power. Group Organ. Stud. 1979, 4, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, B.L.; Rosen, B. Beyond self-management: Antecedents and consequences of team empowerment. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 58–74. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, C.L.; Sims, H.P., Jr. Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: An examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2002, 6, 172–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S.; Robert, C. Empowerment, organizational commitment, and voice behavior in the hospitality industry: Evidence from a multinational sample. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konczak, L.J.; Stelly, D.J.; Trusty, M.L. Defining and measuring empowering leader behaviors: Development of an upward feedback instrument. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.P.; Justin, J.E.; Pearce, C.L. Empowering leadership: An examination of mediating mechanisms within a hierarchical structure. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, S.; Sambamurthy, V. Leadership of information systems development projects. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. EM 2006, 53, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, J. Empowering leadership, uncertainty avoidance, trust, and employee creativity: Interaction effects and a mediating mechanism. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2014, 124, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Bartol, K.M.; Locke, E.A. Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; General Learning Press: Morristown, NJ, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Graen, G.; Dansereau, F., Jr.; Minami, T. An empirical test of the man-in-the-middle hypothesis among executives in a hierarchial organization employing a unit-set analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1972, 8, 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangirala, S.; Green, S.G.; Ramanujam, R. In the shadow of the boss’s boss: Effects of supervisors’ upward exchange relationships on employees. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, T.; Snape, E. Exchange ideology and member-union relationships: An evaluation of moderation effects. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, R.; Yun, S.; Wong, K.F.E. Social influence of a coworker: A test of the effect of employee and coworker exchange ideologies on employees’ exchange qualities. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2011, 115, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.A.; Arad, S.; Rhoades, J.A.; Drasgow, F. The empowering leadership questionnaire: The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring leader behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, A.H.; Chan, W.W. Team creative performance the roles of empowering leadership, creative-related motivation, and task interdependence. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, R.Z.; Lee, G.G. Knowledge management system adoption: Exploring the effects of empowering leadership, task-technology fit and compatibility. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2011, 30, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, M.R.; Bakker, A.B.; Dollard, M.F. Empowering leaders optimize working conditions for engagement: A multilevel study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, S.; Liao, H.; Campbell-Bush, E. Directive versus empowering leadership: A field experiment comparing the impact on task proficiency and proactivity. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1372–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Córcoles, M.; Gracia, F.J.; Tomás, I.; Peiró, J.M.; Schöbel, M. Empowering team leadership and safety performance in nuclear power plants: A multilevel approach. Saf. Sci. 2013, 51, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhonen, T.; Jönsson, S.; Denti, L.; Chen, K. Social climate as a mediator between leadership behavior and employee well-being in a cross-cultural perspective. J. Manag. Dev. 2013, 32, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bass, B.M.; Waldman, D.A.; Avolio, B.J.; Bebb, M. Transformational leadership and the falling dominoes effect. Group Organ. Manag. 1987, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, G.; Lee, S.; Karau, S.J.; Dai, Y. The trickle-down effect of empowering leadership: A boundary condition of performance pressure. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Kuenzi, M.; Greenbaum, R.; Bardes, M.; Salvador, R.B. How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 108, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.M.; Hannah, S.T.; Avolio, B.J.; Kozlowski, S.W.; Lord, R.G.; Treviño, L.K.; Dimotakis, N.; Peng, A.C. Embedding ethical leadership within and across organization levels. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1053–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yammarino, F.J.; Dansereau, F. Multi-level nature of and multi-level approaches to leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Liden, R.C.; Sparrowe, R.T.; Wayne, S.J. Leader–member exchange theory: The past and potential for the future. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1997, 15, 47–119. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G.; Fu, P.P. Determinants of delegation and consultation by managers. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M.; Yukl, G.; Taber, T. Leader behavior and LMX: A constructive replication. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kirkman, B.L.; Kanfer, R.; Allen, D.; Rosen, B. A multilevel study of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S.; Rexwinkel, B.; Lynch, P.D.; Rhoades, L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.; Shore, L.; Taylor, M.S.; Tetrick, L. The Employment Relationship: Examining Psychological and Contextual Perspectives; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Huseman, R.C.; Hatfield, J.D.; Miles, E.W. Test for individual perceptions of job equity: Some preliminary findings. Percept. Mot. Skills 1985, 61, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 2: Methodology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 349–444. [Google Scholar]

- Scandura, T.A.; Graen, G.B. Moderating effects of initial leader–member exchange status on the effects of a leadership intervention. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Stilwell, D. A longitudinal study on the early development of leader-member exchanges. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Green, S.G. Development of leader-member exchange: A longitudinal test. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1538–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.S.; Bedeian, A.G.; Bruch, H. Linking leader behavior and leadership consensus to team performance: Integrating direct consensus and dispersion models of group composition. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I. Psychometry Theory; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P. Leader-member exchange and citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheong, M.; Yammarino, F.J.; Dionne, S.D.; Spain, S.M.; Tsai, C.Y. A review of the effectiveness of empowering leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Panaccio, A.; Meuser, J.D.; Hu, J.; Wayne, S.J. Servant leadership: Antecedents, processes, and outcomes. In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Day, D.V., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 357–379. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bednall, T.C. Antecedents of abusive supervision: A meta-analytic review. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, G.; Karau, S.J.; Dai, Y.; Lee, S. A three-level examination of the cascading effects of ethical leadership on employee outcomes: A moderated mediation analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.L.; Yun, S. A moderated mediation model of the relationship between abusive supervision and knowledge sharing. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, K.S.; Quinn, R.E. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture Based on the Competing Values Framework; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T.; Day, A. Quasi-Experimentation: Design & Analysis Issues for Field Settings; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).