3.1. Results of the Questionnaire

The results of the questionnaire set out the socio-demographic characteristics of the Turkish migrants living in northern Italy. First, the majority of the participants (60% men and 40% women; sample size 544 individuals) reside in the Lombardy (Milan, Como, Lecco, and Varese), Emilia Romagna (Modena and Bologna) and Liguria (Imperia, Turin) regions (

Figure 2).

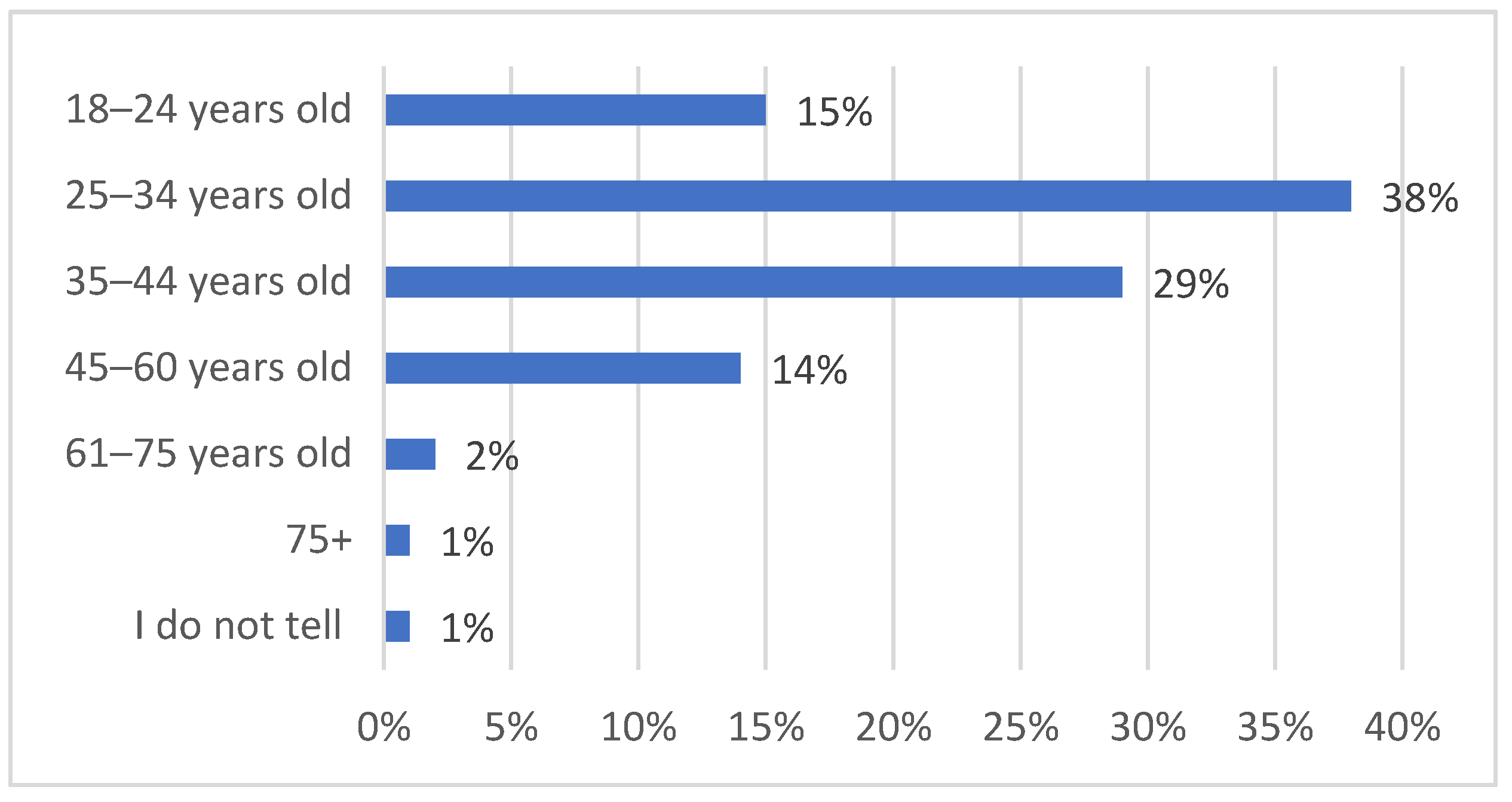

As for the age group of the participants, the highest number of participants was in the 25–34 age group with 38%, and this was followed by the 35–44 age group, with 29% (

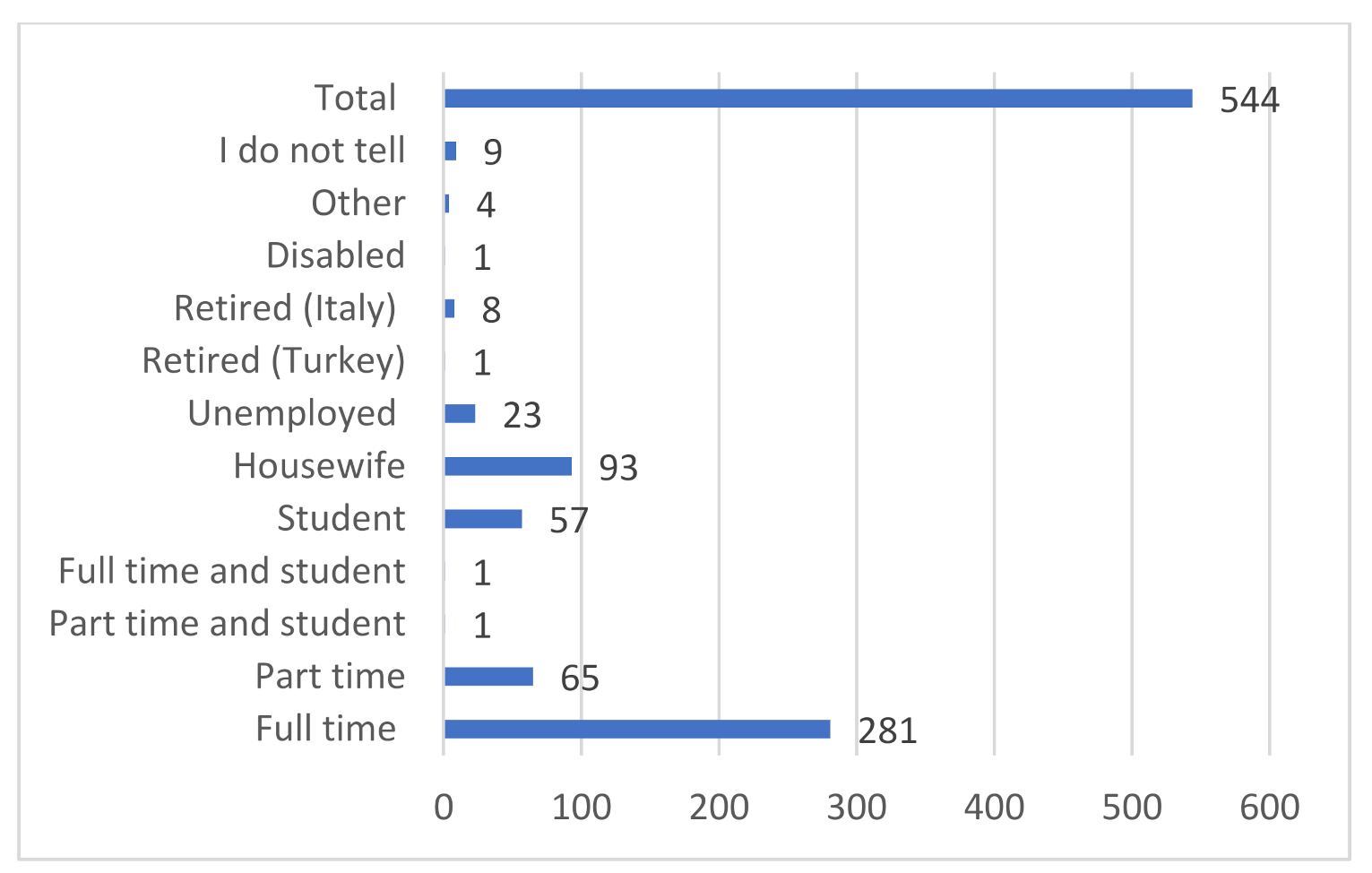

Figure 3). As for the employment status, 53% of the participants were employed full-time, 11% were students, and 17% were housewives, of which 95% came to Italy due to marriage (

Figure 4).

The majority of the participants were from Istanbul, Kahramanmaraş, Sivas, Çorum, Tokat and Ankara in Turkey. A great number of the participants have been residing in Italy for a long time. Overall, 38% of the population have lived in Italy for 10.1–20 years, while 35% have lived for 3.1 to 10 years (sample size: 544 individuals).

Regarding the educational status, the majority were high school graduates, with 30%, followed by elementary school graduates, with 27%. Some participants had never been to elementary school or had left elementary school. Among them, we encountered two illiterate women (sample size: 544 individuals).

The participants were asked questions to comprehend their level of linguistic skills. It was observed that all of the participants can communicate in Italian to various extents. Overall, 17% expressed their capability to handle daily tasks with the level of Italian that they speak, whereas 45% of the participants were confirmed to have a good understanding of the Italian language. Two participants were observed as being as non-Turkish speakers during the questionnaire. More than 40% of the participants can speak one more European language in addition to Turkish and Italian. The majority indicated English as the most widely spoken language among them. French, German and Spanish followed English in this classification (sample size: 544 individuals).

Furthermore, 79% of the participants declared that they speak another language, such as Kurdish or dialect, apart from Turkish, Italian and another European language (sample size: 544 individuals). The participants stated that they speak Turkish, Italian and Kurdish sequentially in their homes. They strongly support the idea of multilingualism by bringing up multi-lingual children who can speak Turkish, Italian, Kurdish and at least one other European language (

Figure 5).

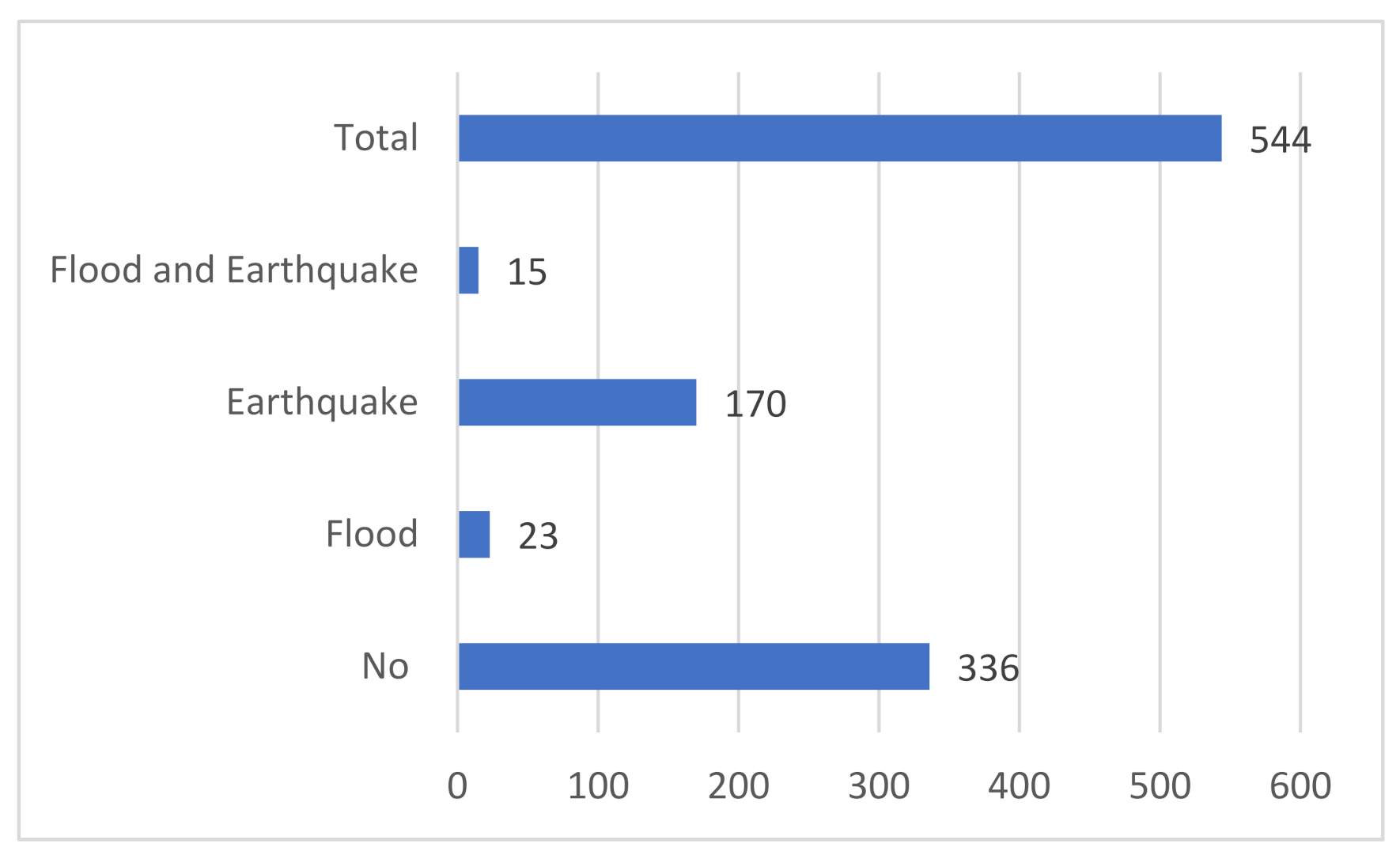

Regarding disaster experience, 31% of the participants confirmed that they had experienced earthquakes and 4% had experienced floods in Italy to ranging extents. In all, 3% of the participants stated that they experienced both disasters (

Figure 6). In particular, the participants from Modena and Milan had incurred monetary and property losses due to earthquake and flood disasters, respectively. One family mentioned that they did not ask for funding from the Italian government as they were not aware of such a mechanism. One person from Modena declared that many families living in Modena returned to Turkey after the occurrence of the Modena Earthquake in 2012.

Anxiety about natural hazards was identified in 63% of the participants. While 11% of the participants declared “excessive anxiety”, 52% of them expressed “anxiety” in characterising their level of concern against disasters.

The majority of the participants were opposed to being self-prepared for disasters, propounding the lack of self-preparedness in Italian society. Even if the participants were quite conscious of the drawbacks of unpreparedness, surprisingly, the overwhelming majority were reluctant to take preventive actions. The participants who had been exposed to disasters in Turkey were perceived as being more susceptible and more predisposed towards the behaviour of “preparedness”.

Only 23% of the participants informed their children about how to act during a natural hazard. Overall, 71% declared their ignorance about how to use “Fire Extinguisher” equipment. Meanwhile, 92% of the participants stated being self-conscious to switch on/off the gas, electricity, and water valves. In all, 87% expressed that they keep their important documents such as passports, insurance and deed papers in somewhat safe places. Overall, 83% of the participants admitted not having an “Emergency Kit” in their home, while 17% do have a “First Aid Kit”. More than 50% of those maintaining a First Aid Kit confessed their ignorance in keeping the necessary medical supplies up to date.

Overall, 83% of the respondents declared not having planned where to reunite in case of an emergency. As a response to the “Where would you prefer going if you were supposed to leave Italy in case of a disaster?” question, while 64% of the participants indicated “Turkey”, the remaining 36% answered “other cities of Italy or Europe” based on the relocation of their extended families.

We presented seven disaster scenarios, including earthquake, flood, drought, snowstorm, pandemic, climate change and fire, to the participants. They were asked to classify them from the most probable (1) to the least (7). Participants declared “flood” as the most likely disaster to occur and “drought” as the least likely one in categorising the disasters for the area of interest.

With the help of this study, we wanted to raise the awareness of Turkish citizens about the risks of natural hazards in their vicinity and enhance their resilience in disaster risk management. For this reason, we asked participants a couple of questions to better understand the most common means of communication to convey “awareness-raising” messages. The responses of the participants showed that not everyone has a smartphone and continuous internet connection. The best means of communication was found to be “SMS” to deliver messages. The participants were asked which social media networks they use the most. More than 400 participants declared having a Facebook account and using it actively in their everyday lives. Therefore, a Facebook account was activated to inform the participants about the recent developments on the topic. We kept the Facebook account active for three years.

During the questionnaire, special topics on which the participants lacked sufficient information in disaster management were revealed, and informative leaflets were prepared to provide accurate information regarding these topics. The leaflets were distributed to the public in the General Consulate of Turkey in Milan. In addition to that, the researchers are currently in collaboration with “Search and Rescue Association” (AKUT) in Istanbul, Turkey, to provide the most accurate responses to the questions such as, “What is a family disaster plan? What are the essential components of an Emergency Kit? How to act during a flood?”. The responses obtained from AKUT Team experts are published periodically as a series of videos via the project’s Facebook page.

3.2. The Results of the Focus Group Meetings

The questionnaire revealed the spatial dispersion of the participants in northern Italy. Most of the population had been identified as settling down in Lombardy (Milan, Lecco, Como and Varese), Emilia-Romagna (Modena and Bologna) and Liguria regions (Imperia). Therefore, we decided to conduct focus group meetings in the Lombardy Region.

During the focus group meetings in Milano, Como, Lecco and Varese, all participants actively participated in the group discussion. We started each focus group meeting with the question of what a disaster is. The generally agreed on definitions are “loss of property”, “loss of life”, “material loss or damage”, and the need for evacuation. During the focus group with women, they defined the disaster as “migration itself is a disaster” and “being prone to Islamophobia” (

Table 2).

Most of the participants had experienced an earthquake or a flood event in Turkey or Italy. Most of the participants stated that a disaster could happen at any moment; some had a fatalistic approach. The participants in Varese experienced the 1999 Izmit earthquake in Turkey, and one of them was in the earthquake’s epicentre. They were still feeling the impact of the event. This group’s awareness level was the highest, and they conducted several emergency drills at their home with their children.

It was clear that the priorities during an emergency and reactions to the situation change according to gender, age, and family presence. The first reaction of women was bringing the family together; the first reaction of men was to understand what’s happening and the extent of the disaster. On the other hand, all students said that the first thing they would do is reach out for their passports and cash.

Most of the women are dependent on their husbands and do not speak Italian. This linguistic incapability creates a barrier for adaptation, isolates them from local society and increases their vulnerability. They seek word of mouth information and communicate with their neighbours or friends who speak the same language. The focus of mothers is their children. They told us that, first, they would seek their children, and after finding them, they would call their husbands for help.

On the other hand, migrants are tightly connected. Their social network is the main resource, especially those isolated due to the language barrier. However, it is still not possible to conclude that the strong sense of community provides resources that make them resilient in the long run, as in some cases, being isolated might be a barrier to reaching out for essential information and resources.