Abstract

Researchers have conducted many empirical studies on the positive effects of ethical leadership. However, they have paid little attention to the antecedents of ethical leadership. This study sought to fill this gap by examining the negative effects of leaders’ perceptions of organizational politics on ethical leadership and the job performance of employees. Accordingly, this study investigated the relationships among them using data collected from 220 dyads of leaders and followers in major companies in South Korea. The results showed that leaders’ perceptions of organizational politics negatively affected their ethical leadership, which, in turn, had an adverse impact on the task performance and organizational citizenship behavior of employees. This paper also provides the theoretical and applied implications of the findings as well as future research directions.

1. Introduction

Recently, the issue of ethical leadership has attracted increasing attention as ethical standards for organizations have been reinforced in modern society. “Ethical leadership” refers to a leader’s moral influence on members in an organization, which ultimately contributes to organizational effectiveness [1]. Accordingly, studies have paid a great deal of attention to the positive influence of ethical leadership on organizational performance, including employees’ task performance and prosocial behavior [2,3]. However, little interest has been directed toward the antecedents of such valuable ethical leadership. Indeed, Frisch and Huppenbauer [4] pointed out that more empirical research on the antecedents of ethical leadership needs to be conducted. Some researchers have emphasized a need for identifying the factors which hamper ethical leadership, which can be treated as challenging problems [1,5,6]. Although organizations with ethical leadership tend to receive favorable reviews from other people, most managers are reluctant to pursue this leadership style for some reason. Therefore, we need to further identify and examine the underlying causes of this inconsistency [3]. Since identifying the factors which hamper ethical leadership can help leaders to eliminate or mitigate this problem, this study analyzes the barriers to ethical leadership in organizations.

Leadership influences employees, not in a vacuum, but in a unique organizational culture [7,8]. Thus, leaders and their styles are significantly affected by the cultural characteristics of the organizations to which they and their employees belong. Moreover, they constantly develop exchange relationships in their organizations. In this regard, their perceptions of organizational politics (POP) can significantly influence their leadership. “Organizational politics” refers to a type of social influence with which individuals behave strategically in order to maximize their profit at someone else’s expense [9]. Leaders with a high POP tend to form a negative exchange relationship with their organizations and are less likely to adopt the exemplary behavior of leaders embracing high ethical standards. Thus, leaders’ POP can serve as a main antecedent that can help predict their behavior regarding ethical leadership. However, most previous studies have only examined employees’ POP as a result of ethical leadership (e.g., Cheng et al., Kacmar et al.) [10,11] or the moderating effects of employees’ POP [12,13]. In overcoming the limitations of previous studies, this study proposes that leaders’ POP serves as an antecedent of their pursuit of ethical leadership.

It also confirms the existence of the comprehensive effect of ethical leadership on the job performance of employees, which is directly related to organizational performance and drives the long-term growth and development of the concerned organization [14,15]. Consequently, the effect of ethical leadership on the job performance of employees has attracted considerable interest from both practitioners and scholars [16]. However, most previous studies adopted research settings located in the West. Additionally, there is a concern about justified unethical behavior in South Korea, which is known for a results-oriented corporate environment and a collective social atmosphere [17,18]. To address these concerns, this study analyzes the relationship between ethical leadership and the job performance of employees in South Korean companies by considering task performance, as an in-role behavior, and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), as an extra-role behavior.

Moreover, this study verifies the indirect effect of ethical leadership under an assumption that ethical leadership is an essential mechanism for linking leaders’ POP and the job performance of employees. In other words, this study first verifies the presumption that leaders’ POP influence the degree of their ethical leadership and then examines the premise that the degree of their ethical leadership is related to job performance, a main outcome by employees. Through these, this study overcomes the limitations of previous studies on ethical leadership and broadens the scope of extant research. It also informs practitioners of organizational efforts to enhance ethical leadership, which is increasingly emphasized in the modern business environment.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Perception of Organizational Politics and Ethical Leadership

Individuals’ POP are about their subjective evaluation of the work environment. Specifically, it reflects their perception of the prevalence of self-centeredness among colleagues and managers in their organization [19]. Leaders’ POP can affect their leadership style. From the perspective of organizational culture, organizational politics influence the attitude and behavior of employees in an organization and set standards for the appropriateness of their behaviors, which has a significant effect on their ethical behaviors [20,21,22]. In addition, organizational politics also affect the leadership behavior of managers, who can adjust their behavior according to the organizational atmosphere [23]. It is noteworthy that middle managers can more effectively sense organizational politics than employees at other levels [24]. Nevertheless, most previous studies on POP focused on employees’ perceptions of organizational politics [10,11,25]. In particular, some researchers have suggested that the leader’s ethical behaviors affect employees’ POP or that employees’ POP moderate the relationship between ethical leadership and their performance. However, with the importance of the leaders’ POP in the organization, it is necessary to examine how the leaders’ perceptions of organizational politics affect their ethical leadership.

POP can be inferred based on individual–organization exchange relationship. Individuals work for an organization, with the expectation that they will receive material (e.g., money) and psychosocial (e.g., gratitude and respect) rewards [26,27]. However, when individuals sense the prevalence of organizational politics in their organizations, they become concerned about the possibility of receiving rewards that depend on power but not objective performance. They also raise questions as to whether their organizations are operated fairly and why their organizations do not fulfill responsibilities in supervising and providing guidelines appropriately [28,29,30]. Additionally, individuals are afraid they will have to work in an organizational environment with limited resources, which prompts conflicts and factional behavior as people compete for those limited resources. Consequently, they may believe that organizations may be indifferent to their concerns and stop resorting to the organization for their psychosocial needs, such as respect [26]. In such an environment, individuals tend to leave their current jobs by changing their positions, concentrate on their work alone, or participate in organizational politics to enhance their influence and self-interest [9].

Based on previous studies, we can argue that leaders’ POP are likely to have a negative impact on the exchange relationship between them and the organization. To become ethical leaders, leaders should devote more time and effort to completing their tasks (e.g., providing goals and feedback) and implementing relational behavior (e.g., supporting and encouraging) [31]. However, in an environment with a high degree of perceived organizational politics, leaders tend to handle official tasks with minimum effort and avoid investing their resources in extra behavior that is essential to improved work performance [9,11,32]. In other words, they reduce resources used in their unbalanced exchange relationship with unfair and indifferent organizations to regain a new balance [28]. They can also achieve such a balance by participating in organizational politics to maximize their profits. However, those involved in organizational politics are likely to achieve this at the cost of other organizational members, which is against the intended goals of ethical leaders who pursue a high standard of morality [33]. In this regard, leaders’ POP can negatively influence their ethical leadership. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 1(H1).

Leaders’ perceptions of organizational politicsare negatively related to ethical leadership.

2.2. Ethical Leadership and Job Performance

The modern business environment emphasizes corporate social responsibility and ethics for sustainable growth, now more than ever. Thus, the issue of ethical leadership, which directly affects the job performance of employees, receives a great deal of attention from scholars and practitioners [16]. Studies on job performance have been classified into those that focus on either task performance, based on in-role behavior, or OCB, based on extra-role behavior [34]. As a result, this study examines the relationship between ethical leadership and the task performance and OCB of organizational members.

Social learning processes and social exchange perspectives provide a theoretical basis for the relationship between ethical leadership and the job performance of employees. First, social learning theory [35] states that employees learn what they should and should not do in organizations by observing the behavior of their leaders. Such social learning processes serve as a theoretical foundation for connecting the ethical behavior of leaders and the positive behavior of members [16]. Based on their position, leaders rely on their power to grant rewards to employees accomplishing tasks well and exhibiting desirable behavior, or mete out punishments to prevent them from taking actions prohibited by the organization.

Second, social exchange theory [36], based on a reciprocity norm, indicates that the beneficial behavior of people in an exchange relationship helps them establish a sense of mutual obligation that is based on trust and exhibit desirable behavior [37]. Therefore, when leaders trust and respect employees in an organization and exhibit honesty, employees increase their constructive behavior in order to get rewards from their leaders and organizations. Consequently, the task performance and the OCB of employees increases. Many previous studies showed that ethical leadership is positively related to employee task accomplishment [2,25]. For example, Mayer et al. [2] found that the ethical leadership of CEOs had a positive impact on the ethical leadership of managers and increased the OCB of groups. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 2a(H2a).

Ethical leadership is positively related to the task performance of employees.

Hypothesis 2b(H2b).

Ethical leadership is positively related to the OCB of employees.

2.3. Mediating Effects of Ethical Leadership

Following the above arguments, this study postulates that ethical leadership is a mechanism linking leaders’ POP and the job performance of employees. First, this study suggests that leaders are less likely to demonstrate ethical leadership if they observe the presence of active organizational politics. The ethical influence of leaders is directly related to the job performance of employees. Consequently, the job performance of employees can decrease when leaders exhibit unethical behavior. Employees tend to consider the behavior of leaders to be standards for responding to ethical issues. Accordingly, they may not trust leaders who exhibit unethical behavior or do not provide appropriate ethical guidelines [16,38]. Therefore, leaders’ POP and the job performance of employees can be connected through ethical leadership.

Second, an unethical attitude adopted by leaders may imply that organizations are not committed to fairness or their employees. As a result, employees might ignore organizational goals and stop putting in effort to ensure that their organizations flourish [26]. Based on the aforementioned discussions, we propose:

Hypothesis 3a(H3a).

Ethical leadership mediates the relationship between leaders’ perceptions of organizational politics and the task performance of employees.

Hypothesis 3b(H3b).

Ethical leadership mediates the relationship between leaders’ perceptions of organizational politics and the OCB of employees.

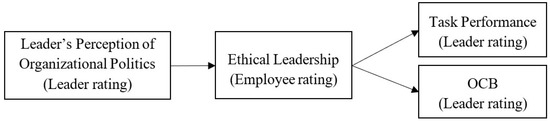

Figure 1 shows the hypothesized model.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

To test the hypotheses, we conducted surveys of employees and their immediate leaders in major South Korean firms which are classified as large companies in terms of their total assets. During the survey, a leader was allowed to evaluate only one immediate employee of their organization. Questionnaires were distributed to 335 pairs of leaders and employees. We collected 262 (78.2%) and 244 questionnaires (72.8%) from employees and leaders, respectively. The questionnaires that showed inconsistency in pairing or that included unreliable responses or missing values were excluded. The data of 220 pairs of leaders and employees were eventually used for statistical analyses. The characteristics of the sample of leaders were as follows: They were 42.07 years old on average (standard deviation = 6.12) and the numbers of men and women were 122 (55.5%) and 98 (44.5%), respectively. In terms of academic background, most of the leaders were university graduates. They had worked in their companies for 13.41 years on average (standard deviation = 6.54).

The employees were 34.18 years old on average (standard deviation = 5.58). The numbers of male and female employees were 99 (45.0%) and 121 (55.0%), respectively. Most of the employees were university graduates. The employees had worked in their companies for 6.31 years on average (standard deviation = 4.90). Additionally, the leaders and employees had worked together for 2.09 years on average (standard deviation = 2.32) in their companies.

3.2. Measures

The variables used in this study were divided into independent, mediator, dependent, and control variables. All items, except the control variables, were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The leaders assessed their POP and employees’ task performance and OCB, while employees assessed their leaders’ ethical leadership.

Perception of organizational politics. POP was measured by six items proposed by Hochwarter et al. [26]. The leaders were asked to rate statements, such as the following: “Many employees are trying to maneuver their way into the in-group.”

Ethical leadership. Ethical leadership was evaluated based on 10 items proposed by Brown et al. [16]. The subordinates of leaders were asked to write statements to rate. The following is an example: “My supervisor sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics.”

Task performance. Employees’ task performance was evaluated based on seven items proposed by Williams and Anderson [34], such as “This employee fulfills responsibilities specified in the job description.”

Organizational citizenship behavior. Employees’ OCB was evaluated based on 14 items proposed by Williams and Anderson [34]. Leaders formulated the questionnaires with items, such as “This employee helps others who have heavy workloads” and “This employee adheres to informal rules devised to maintain order.”

Control variables. We controlled for leaders’ and employees’ age, gender, education, and tenure in their organization based on the results of previous studies to identify relationships among the variables used in the models [10,25]. In addition, given that the periods of service during which the leaders and employees worked together are likely to affect supervisor ratings, we controlled for tenure with a leader.

4. Results

Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, correlation coefficients, and confidence coefficients of the variables used in the analyses. The confidence coefficients for leaders’ POP, ethical leadership, task performance, and OCB are high, at 0.96, 0.95, 0.93, and 0.91, respectively. Moreover, the results of the analysis of the relationships between the variables and descriptive statistics in this study are consistent with those in previous studies.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Table 2 presents the relationship between leaders’ POP and ethical leadership, and the relationship between ethical leadership and the job performance of employees. According to Hypothesis 1, leaders’ POP and ethical leadership might have a negative relationship. First, Model 2, applying leaders’ POP, was analyzed under the condition of controlled demographic variables. The results of the analysis showed that leaders’ POP had a statistically significant negative effect on ethical leadership (β = −0.21, p < 0.01). Based on this result, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Hypothesis 2 predicts that ethical leadership might have a positive relationship with the task performance of employees (2a) and their OCB (2b). The results of Model 5 shown in Table 2 confirmed a significant positive relationship between ethical leadership and the task performance of employees (β = 0.20, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 2a is thus supported. The results of Model 8 also confirmed a significant positive relationship between ethical leadership and the OCB of employees (β = 0.28, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2b.

Table 2.

Regression results for mediation.

Hypotheses 3a and 3b predict that ethical leadership mediates the relationship between leaders’ POP and the job performance of employees. The bootstrap verification method developed by Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes [39] was used to verify the indirect effect of ethical leadership. Table 3 shows the results of the bootstrap method. Regarding the indirect effect of ethical leadership on the relationship between leaders’ POP and the task performance of employees, verification was conducted 10,000 times within the 95% confidence interval (CI). The bootstrapping results showed that 0 was not included (LL 95% CI = −0.06, UL 95% CI = −0.01), confirming the indirect effect of ethical leadership. This result supports Hypothesis 3a. To test the indirect effect of ethical leadership on the relationship between the leaders’ POP and the OCB of employees, we used the same verification process. The results again showed that 0 was not included (LL 95% CI = −0.07, UL 95% CI = −0.01), confirming the indirect effect of ethical leadership, supporting Hypothesis 3b.

Table 3.

Bootstrap results for indirect effect.

5. Discussion

As interest in the effects of ethical leadership on organizational performance has increased, research on ethical leadership has also expanded. However, studies have paid little attention to the antecedents of ethical leadership, especially those that have a negative impact. Although leaders agree that ethical leadership is useful in various ways, they might find it difficult to practice it. In this regard, an analysis of the antecedents that have a negative impact on ethical leadership can provide implications for researchers who analyze ethical leadership in different fields and organizations that aim to foster ethical leaders.

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study has the following theoretical implications. First, this study examines POP as an antecedent of ethical leadership. Existing studies on ethical leadership have analyzed POP as a dependent factor of ethical leadership, or as a moderating variable [10,11,25]. For example, Cheng et al. [10] demonstrated that ethical leadership is negatively related to employee-perceived organizational politics, which in turn decreased their internal whistleblowing. In addition, Kacmar et al. [25] suggested that employees’ perceptions of politics moderate the relationship between ethical leadership and both person- and task-focused organizational citizenship behavior. However, this study showed that leaders are affected by the organizational environment and can adjust their leadership behavior according to the environment. Moreover, as Frisch and Huppenbauer [4] point out, empirical research on antecedents of ethical leadership is still very rare and has mainly focused on the individual characteristics of the leader, such as the leader’s conscientiousness, agreeableness [40] and emotional stability [40]. This study filled this gap by demonstrating that the degree to which leaders perceive the politics of an organization can be a major influencing factor of their level of ethical leadership. Thus, it is expected that future studies can analyze the effect of POP more accurately by verifying its influence as an antecedent for leadership behavior.

Second, this study found that the ethical behavior of leaders had positive effects on the job performance of employees, verifying the effectiveness of ethical leadership. This result is consistent with the findings of previous studies [2,25]. Numerous meta-analyses based on the accumulated data of studies on ethical leadership have been conducted recently. The results of the empirical analyses undertaken in this study confirmed a positive correlation between task performance and the OCB of employees and ethical leadership [3,41]. This finding suggested that ethical leadership had a significant impact on increasing the job performance of employees in East Asian cultures, which is consistent with the findings of several empirical analyses that have been conducted recently.

Third, this study highlighted the influence of a negative antecedent of ethical leadership and performance outcomes. Specifically, this study indicated that that the more that leaders perceive their organizations as political, the lower their ethical leadership and the performance of employees will be. Moreover, several scholars have called for more cross-cultural studies on POP (e.g., Harris & Kacmar) [42], suggesting that some cultural characteristics may influence POP and that previous research on POP was mainly conducted in North American [43]. In particular, Bedi and Schat [43] argued that employees in cultures with a more significant power distance may consider political behaviors to be more acceptable and, thus, less likely to cause negative outcomes. In addition, employees in more collectivistic cultures may be less sensitive to self-interested behavior and be less likely to react negatively to it [44]. As a result, this study provides an important theoretical contribution in that it examined the relationship between POP and ethical leadership in East Asia, especially in South Korea, rather than in the West.

Furthermore, this study has the following implications for organizations. First, organizations should strive to reduce POP from the perspective of organizational culture management because it can frustrate ethical leadership. Middle-level managers, in particular, are more sensitive to recognition and rewards, such as promotion and more acutely aware of POP than upper- and lower-level employees. Therefore, organizations should provide an environment where middle-level managers can assure themselves that organizational politics are not prevalent. For example, organizations should emphasize transparency and fairness in decision-making and establish systematic standards and structures that stress ethical behavior.

Second, this study indicates that ethical leadership directly affects the main variables related to the performance of employees. Based on this result, organizations are encouraged to provide various training and education programs that can actively encourage leaders to demonstrate ethical and desirable behavior and demonstrate their ethical leadership to employees in an organization.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study analyzed the negative antecedent of ethical leadership, which has not been investigated to date, in order to widen the scope of research on ethical leadership. Nevertheless, it has several limitations, including the representative issue that is characteristic of cross-sectional studies. Although a longitudinal research design is an effective method of investigating antecedents, ethical leadership, and organizational performance, this study did not use this method owing to practical difficulties. However, it conducted a survey on the antecedents of leaders demonstrating ethical leadership, a survey on ethical leadership using employees who were directly related to these leaders, and a survey on the job performance of these employees who worked with the aforementioned leaders. It seems clear that these surveys partly solve the problem of common method bias. In addition, even though POP and ethical leadership were rated by different subjects, the issue of endogeneity may be raised in this study. It means that the existence of such an unobservable variable that influence both POP and ethical leadership simultaneously will lead to a biased estimation of coefficient [45]. Therefore, in future research, it will be necessary to design a study that addresses the issue of endogeneity.

Moreover, this study focused on identifying the negative antecedent of ethical leadership. Future research should examine various mediator and moderator variables, which were not included in the present research model. In addition, several variables, such as reliability and fairness, should be considered as mediator variables for the relationships between negative antecedents and ethical leadership. Thus, future research could produce interesting findings by analyzing complicated interactions among antecedents. As leadership is an interaction between leaders and employees, meaningful insight can be gained from analyzing the interaction between ethical leadership and employees’ POP from the perspective of social exchange.

A host of existing studies emphasize the positive effects of ethical leadership. However, it is inevitable for leaders to be affected by various factors when exercising ethical leadership, given that they also interact with numerous interested parties in organizations. Therefore, researchers should conduct further studies to identify the factors that inhibit ethical leadership, which can ultimately enable the widespread application of ethical leadership in organizations. In addition, since the firm size in our study can be a key variable that can influence the independent and dependent variables simultaneously, firm size should be fully considered in future studies [46].

6. Conclusions

In order for an organization to be sustainable in the long-term, it needs to be ethical and socially justified. Accordingly, there has been increasing interest in ethical leadership in both organizations and society. Despite the significance of ethical leadership, factors hampering ethical leadership are prevalent in business environments. Thus, this study focused on the antecedents that have a negative impact on ethical leadership by demonstrating the effects of leaders’ perceptions of organizational politics on ethical leadership and employees’ job performance. All in all, we expect that our findings will contribute to the literature on ethical leadership and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and G.B.; methodology, G.B.; software, J.K.; validation, S.L. and G.B.; formal analysis, J.K.; investigation, G.B.; resources, S.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and G.B.; visualization, J.K.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea(NFR-2019S1A5A8033908).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Kuenzi, M.; Greenbaum, R.; Bardes, M.; Salvador, R. (Bombie) How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 108, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Ethical leadership: Meta-analytic evidence of criterion-related and incremental validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 948–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, C.; Huppenbauer, M. New insights into ethical leadership: A qualitative investigation of the experiences of executive ethical leaders. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ko, C.; Ma, J.; Bartnik, R.; Haney, M.H.; Kang, M. Ethical leadership: An integrative review and future research agenda. Ethics Behav. 2018, 28, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; Nieuwenboer, N.A.D.; Kish-Gephart, J.J. (Un)Ethical behavior in organizations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 635–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, F.E. The contingency model and the dynamics of the leadership process. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 59–112. [Google Scholar]

- Oc, B. Contextual leadership: A systematic review of how contextual factors shape leadership and its outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G.R.; Russ, G.S.; Fandt, P.M. Politics in organizations. In Impression Management in the Organization; Giacalone, R.A., Rosenfeld, P., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Bai, H.; Yang, X. Ethical leadership and internal whistleblowing: A mediated moderation model. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacmar, K.M.; Andrews, M.C.; Harris, K.J.; Tepper, B.J. Ethical leadership and subordinate outcomes: The mediating role of organizational politics and the moderating role of political skill. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başar, U.; Filizöz, B. Can ethical leaders heal the wounds? An empirical research. Eurasian J. Bus. Econ. 2015, 8, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, K.; Johnson, D.E.; Avey, J. Going against the grain works: An attributional perspective of perceived ethical leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.J.; Kacmar, K.M.; Zivnuska, S. An investigation of abusive supervision as a predictor of performance and the meaning of work as a moderator of the relationship. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.S.; Ambrose, M.L. Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-H.; Yoon, J. The origin and function of dynamic collectivism: An analysis of Korean corporate culture. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2001, 7, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, S.; Yang, I. Whither seniority? Career progression and performance orientation in South Korea. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 1419–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G.R.; Harrell-Cook, G.; Dulebohn, J.H. Organizational politics: The nature of the relationship between politics perceptions and political behavior. Res. Sociol. Organ. 2000, 17, 89–130. [Google Scholar]

- Drory, A. Perceived political climate and job attitudes. Organ. Stud. 1993, 14, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K. Ethical decision-making in organizations: A person–situation interactionist model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B. When employees do bad things for good reasons: Examining unethical pro-organizational behaviors. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.; Lippitt, R. Leader behavior and member reaction in three social climates. In Group Dynamics: Research and Theory, 3rd ed.; Cartwright, D., Zander, A., Eds.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.P.; Dipboye, R.L.; Jackson, S.L. Perceptions of organizational politics: An investigation of antecedents and consequences. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 891–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacmar, K.M.; Bachrach, D.G.; Harris, K.J.; Zivnuska, S. Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hochwarter, W.; Kacmar, C.; Perrewé, P.L.; Johnson, D. Perceived organizational support as a mediator of the relationship between politics perceptions and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, H. Reciprocation: The relationship between man and organization. Adm. Sci. Q. 1965, 9, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Rosen, C.C.; Levy, P.E. The relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and employee attitudes, strain, and behavior: A meta-analytic examination. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, A.T.; Hochwarter, W.A.; Ferris, G.R.; Bowen, M.G. The dark side of politics in organizations. In The Dark Side of Organizational Behavior; Griffin, R.W., O’Leary-Kelly, A.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 237–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hochwarter, W.; Perrewé, P.; Ferris, G.; Guerico, R. Commitment as an antidote to the tension and turnover consequences of organizational politics. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 55, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-H.J.; Ma, J.; Johnson, R.E. When ethical leader behavior breaks bad: How ethical leader behavior can turn abusive via ego depletion and moral licensing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gotsis, G.N.; Kortezi, Z. Ethical considerations in organizational politics: Expanding the perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 93, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, M.; Kacmar, K.M.; Zivnuska, S. Understanding the effects of political environments on unethical behavior in organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, J.M.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Mayer, D.M. My boss is morally disengaged: The role of ethical leadership in explaining the interactive effect of supervisor and employee moral disengagement on employee behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multiv. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalshoven, K.; Hartog, D.N.D.; De Hoogh, A.H.B. Ethical leader behavior and big five factors of personality. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A.; Alpaslan, C.M.; Green, S. A Meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Kacmar, K.M. Easing the strain: The buffer role of supervisors in the perceptions of politics-strain relationship. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2005, 78, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A.; Schat, A. Perceptions of organizational politics: A meta-analysis of its attitudinal, health, and behavioural consequences. Can. Psychol. Can. 2013, 54, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romm, T.; Drory, A. Political behavior in organizations—A cross-cultural comparison. Int. J. Value-Based Manag. 1988, 1, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Endogeneity in CEO power: A survey and experiment. Invest. Anal. J. 2016, 45, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, C. Measuring firm size in empirical corporate finance. J. Bank. Financ. 2018, 86, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).