Interaction as a Central Element of Co-Creative Wine Tourism Experiences—Evidence from Bairrada, a Portuguese Wine-Producing Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Wine Tourism Experiences

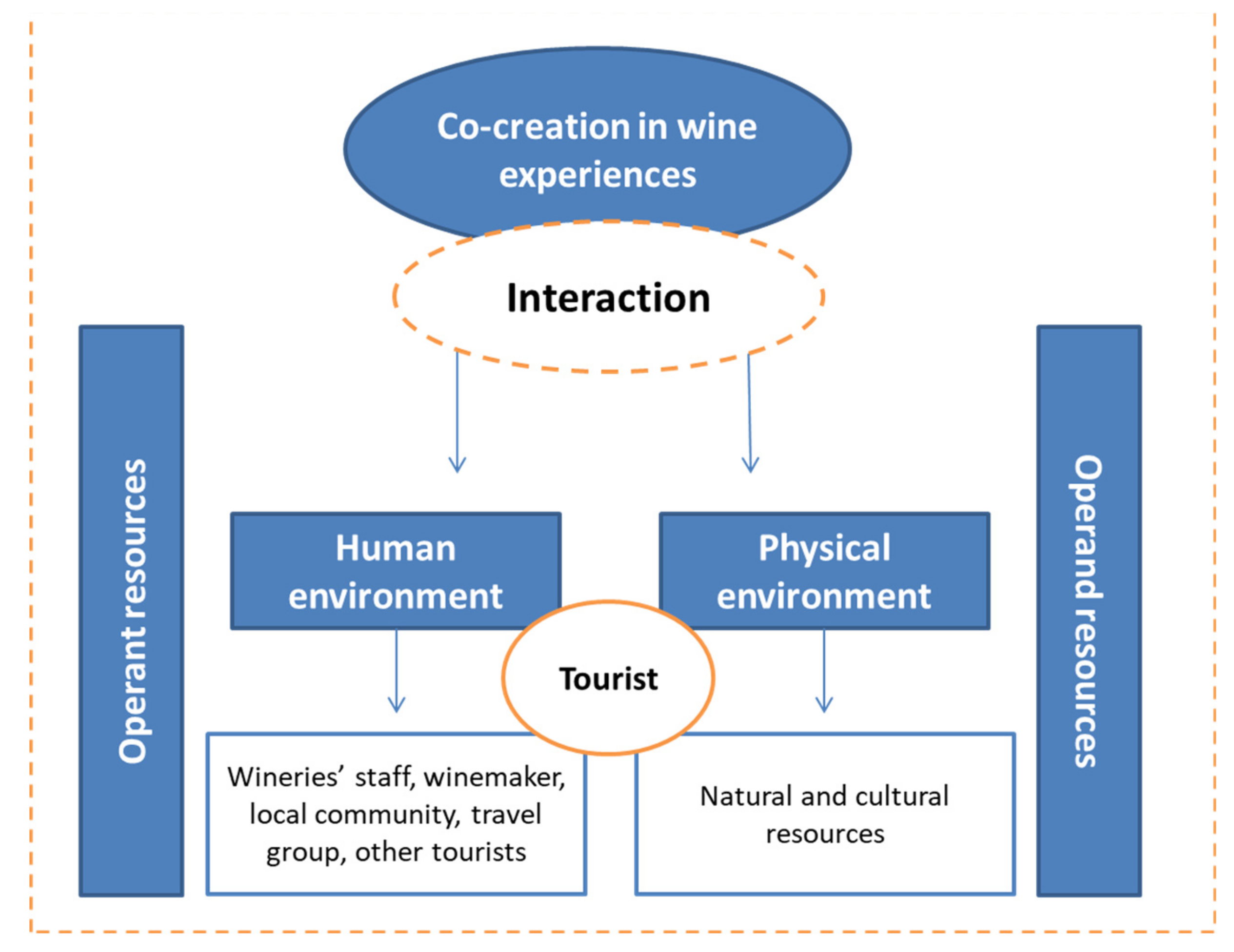

2.2. Tourism Co-Creation and Co-Creative Wine and Food Tourism Experiences

2.3. Interaction and Its Relevance in Wine Tourism Experiences

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Rota da Bairrada

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Co-Creative Wine, Natural and Cultural Tourism Experiences in Bairrada

“They are usually regions that in themselves have certain characteristics associated with a certain context, with a certain history, most often associated with wine production itself, but they are also areas with […] a certain way of being that distinguishes [them] from other regions.”(V5_Female, 34 years old)

“We really like to participate in the experience and see where the wine is produced, where the grapes are harvested, the transformation process and have contact with the local community for a more wine-guided history.”(V16_Male, 35 years old)

“[I’m motivated by] the context, the contact with nature, the peace, the opportunity to do things different from usual... not exactly because of the wine.”(V30_Female, 33 years old)

Some visitors, who tend to travel to wine regions for other motivations also mentioned that wine usually “comes as a very good addition”.(V20_Female, 47 years old)

“The history of the wine and food and explanation of how they make it and the romance, you know, behind.”(V13_Male, 56 years old)

“Wine encompasses a lot more than the drink itself. When you hear about the history behind the brand, you start to appreciate it even more. That’s really interesting to me.”(V16_Male, 35 years old)

“(…) the sharing of information... I think this is what makes the difference between a wine tasting in a generalized context and in a specific region where there is always a unique impression and a brand associated with the region.”(V5_Female, 34 years old)

“What is really interesting is when we go to a winery, it’s a farm, it’s agriculture, and so we don’t think about this when drinking at home for dinner. So, that’s like the combination of going to a farm and then having this wine tasting experience and amazing food, all that stuff coming together is really interesting.”(V14_Female, 54 years old)

[Local people are] “also very genuine, because in Belgium, if you walk or make a bicycle tour it happens that nobody says ‘hi!’… [I was] surprised and here everybody says ‘Bom dia’, ‘Boa tarde’, everybody!”(V21_Male, 48 years old)

“People from Bairrada are friendly and welcoming, this is also very touching for us in Bairrada.”(V16_Male, 35 years old)

“Baga [a regional grape variety] makes a distinction, there are many characteristics of the region that mark […] and this is really valuable.”(V5_Female, 34 years old)

“The wine from Bairrada is not a wine for mass consumption and has to be sold as such.”(V5_Female, 34 years old)

“All the wonderful food and the traditional food and the combination of things … I really enjoyed having a full understanding of what local food is.”(V13_Male, 56 years old)

4.2. Interaction with the Physical Environment

“The surprise when you arrive with your bike, enter the gate and then you see this [pointing at the beautiful garden of the rural accommodation unit] from this place, for example, you enter the door, and there’s such a paradise garden, it was everywhere like this.”(V8_Female, 61 years old)

“There are very specific vineyards, that vineyard that runs on a very gentle hill… Then in autumn, you get some funny colors, then it’s cute, because of the different varieties… The leaves start to change at different times. So... going by the region in October, you can delight yourself with the colors… some are already yellow, others are still green…”(V5_Female, 34 years old)

“The moment I was there… it’s something that isn’t that fast […] it’s a personal experience that is real… and the difference is the fact that you are experiencing an ancient tradition […] and suddenly you see yourself being part of the wine production process, not from a touristic perspective but like the locals do, working beside them. For me, it was a reflexive moment.”(V18_Female, 32 years old)

4.3. Interaction with the Human Experiencescape

“Today, in the experience of harvesting I had the opportunity to meet a man in his 70s who works here since he was a young boy… you know, getting to know the people… I think this is important.”(V17_Female, 34 years old)

“A moment of personal reflection […] more than a wine tasting in which you are always with people… it is surprising from the point of view of being different and for not being very touristy […] being together with the staff, we had lunch with them, so there was nothing created for us [as tourists], on the contrary, so it was interesting due to that [opportunity].”(V18_Female, 32 years old)

“People are simple, but extremely welcoming… they want visitors to be always very comfortable and want to help and offer something […] people are very simple, communication is very simple, too.”(V16_Male, 35 years old)

“One thing that we like and that we have noticed is the exchange of experiences, they [staff] ask where we come from, what we do and we always have that mutual interest of wanting to know how it started, what they do besides this… well, the harvest is only a short time, and the rest of the year what do they do, what are the plans, the dreams… […] this contact has always been very interesting.”(V18_32 years old)

“I was surprised, almost nobody speaks English so we can’t really talk, but everybody is so friendly and open.”(V8_Female, 61 years old)

“That’s a highlight, of course, travelling with my friends… it’s the highest highlight.”(V8_ Female, 61 years old)

“The first time we were here [in the official store of Bairrada route association] on a wine tasting with three other people we had never been with, the store closed and we ended up outside, at a picnic table, sitting with three gentlemen we didn’t know before, drinking a bottle of sparkling wine and talking about things… (laughs). We will never see them again, in fact, but it was an experience that stayed in our memories […] When I talk about this experience, I say ‘it was really cool’ and I think that’s what people are increasingly looking for, something that is a different experience.”(V5_Female, 34 years old)

“[about the region’s marketing] the region has to be distinguished for its human component, in a globalized society […] it makes a difference.”(V5_34 years old)

This idea was reinforced by another visitor who considered that “people are undoubtedly a reference and a great attraction […] going to a place and getting to know the winery or who is the winemaker, meeting the people is special.”(V18_Female, 32 years old)

“Their history and how they do it, they told us the whole history of the buildings and of the land and also what they are doing, how they are handling the grapes, what they put in it, for how long, everything, so, we know the hard work.”(V13_Male, 56 years old)

“As Americans, our history goes back not many generations. Today we talked about his family’s winery [Luís Pato winemaker] and it being in the family’s business for generations… we don’t have that, so it’s really fascinating to us, this winery… his great-great-great grandfather started.”(V14_Female, 54 years old)

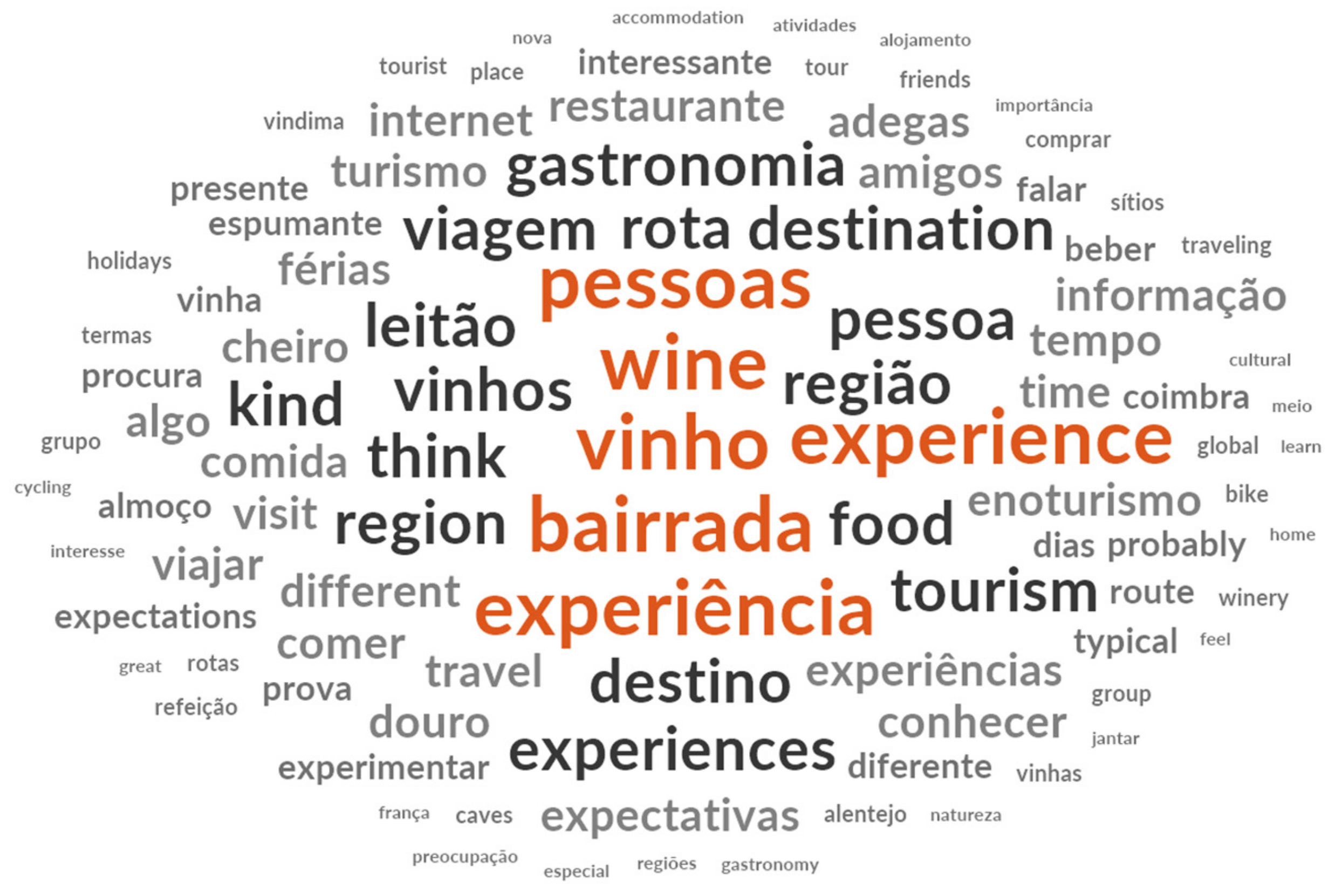

4.4. Word Cloud

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- -

- What do you expect to experience in these destinations?

- -

- What do you consider most typical of this Region?

- -

- Given the experience on the Bairrada Route, how would you describe it?

- -

- What activities did you engage in and which places did you visit?

- -

- What did you learn?

- -

- In what way were your senses stimulated?

- -

- How do you characterize the contact you had with other people (staff, residents, other tourists) during the experience?

References

- Brochado, A.; Stoleriu, O.; Lupu, C. Wine tourism: A multisensory experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charters, S.; Ali-Knight, J. Who is the wine tourist? Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Ben-Nun, L. The important dimensions of wine tourism experience from potential visitors’ perception. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, B. Understanding the wine tourism experience for winery visitors in the Niagara region. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 7, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.; Vilijoen, A. Terroir wine festival visitors: Uncorking the origin of behavioural intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 24, 616–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D.; Carneiro, M.J.; Kastenholz, E. “Velho Mundo” versus “Novo Mundo”: Diferentes perfis e comportamento de viagem do enoturista? Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2020, 34, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. O potencial do enoturismo em áreas rurais: Perspetivas do projeto TWINE. In Proceedings of the III Encuentro Iberoamericano de Turismo Rural, Évora, Portugal, 29 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, T. Opportunities and pitfalls of tourism in a developing wine industry. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1995, 7, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Vicente, G.; Martín Barroso, V.; Blanco Jiménez, F.J. Sustainable Tourism, Economic Growth and Employment—The Case of the Wine Routes of Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, T.; Smit, B.; Jones, G. Toward a conceptual framework of terroir tourism: A case study of the Prince Edward county, Ontario wine region. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Marques, C.P.; Carneiro, M.J. Place attachment through sensory-rich, emotion-generating place experiences in rural tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100455, ISSN 2212-57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, R.; Stone, M.; Wolf, E.; Pozzi, A. Wine travel in the United States: A profile of wine travellers and wine tours. Tour. Manag. Perspect 2017, 23, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Cunha, D.; Eletxigerra, A.; Carvalho, M.; Silva, I. Exploring Wine Terroir Experiences: A Social Media Analysis. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems; ICOTTS 2020. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Abreu, D., Liberato, E.A., González, J.C., Ojeda, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 209, pp. 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- Binkhorst, E.; Dekker, T.D. Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.; Mendes, J.; do Valle, P.; Scott, N. Co-creation experiences: Attention and memorability. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1309–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.; Gilmore, J. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Co-creation experiences. In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing; Buhalis, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1225–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachão, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V. Drivers of experience co-creation in food-and-wine tourism: An exploratory quantitative analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Flagship attractions and sustainable rural tourism development: The case of the alnwick garden. England. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, E.; Cambourne, B.; Macionis, N. Wine Tourism around the World: Development, Management and Markets; Butterworth-Heinemann: Auckland, New Zealand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, J.; Prayag, G.; Disegna, M. Why wine tourists visit cellar doors: Segmenting motivation and destination image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 20, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. A co-criação de experiências enogastronómicas: O caso da rota da Bairrada. J. Tour. Dev. 2021, 36, 325–339. [Google Scholar]

- Novo, G.; Osorio, M.; Sotomayor, S. Wine tourism in Mexico: An initial exploration. Anatolia 2019, 30, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.; Getz, D. Profiling potential food tourists: An Australian study. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, P.; Laing, J.; Frost, W.; Williams, K. Trends in experience design—Strategies for attracting millennials to wineries in Victoria, Australia. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Experience Management and Marketing; Dixit, S.K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Malerba, R.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Family-friendly tourism supply. In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing; Buhalis, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Wiu, H.; King, B.; Huang, S. Understanding the wine tourism experience: The roles of facilitators, constraints, and involvement. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.; Fiore, A.M. Destination loyalty: Effects of wine tourists’ experiences, memories, and satisfaction on intentions. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 13, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, R.; Lowry, L.; Higgins, L. Exploring a wine farm micro-cluster: A novel business model of diversified ownership. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 27, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W.; Frost, J.; Strickland, P.; Maguire, J. Seeking a competitive advantage in wine tourism: Heritage and storytelling at the cellar-door. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Almeida, N.; Santos-Pavón, E. Wine and wine tourism experience: A theoretical and conceptual review. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Wine tourism in New Zealand. In Tourism Down under II: Towards a More Sustainable Tourism; Kearsley, G., Ed.; Centre for Tourism, University of Otago: Dunedin, New Zealand, 1996; pp. 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.; Bruwer, J. Regional Brand image and perceived wine quality: The consumer perspective. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2007, 19, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, J.; Prebensen, N. The effect of co-creation experience on outcome variable. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prahalad, C.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minkiewicz, J.; Evans, J.; Bridson, K. How do consumers co-create their experiences? An exploration in the heritage sector. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 30–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.; Vittersø, J.; Dahl, T. Value co-creation significance of tourist resources. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihova, I.; Buhalis, D.; Moital, M.; Gouthro, M. Conceptualizing customer-to-customer value co-creation in tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, E.; Mele, C. Marketing as value co-creation through network interaction and resource integration. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2010, 4, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carvalho, M.; Lima, J.; Kastenholz, E.; Sousa, A. Co-creative rural tourism experiences: Connecting tourists, community and local resources. In Meeting Challenges for Rural Tourism through Co-Creation of Sustainable Tourist Experiences; Kastenholz, E., Carneiro, M.J., Eusébio, C., Figueiredo, E., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016; pp. 79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J.; Marques, C.P.; Lima, J. Understanding and managing the rural tourism experience: The case of a historical village in Portugal. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, C.; Camarero, C.; Garrido, M.J. Exploring the experience value of museum visitors as a co-creation process. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1406–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Choi, H.-S. Developing and validating a multidimensional tourist engagement scale (TES). Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 469–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonincontri, P.; Morvillo, A.; Okumus, F.; van Niekerk, M. Managing the experience co-creation process in tourism destinations: Empirical findings from Naples. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G.; Chen, Y. Co-Creation Tourism in an Ancient Chinese Town. J. China Tour. Res. 2019, 16, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Bai, C.; Li, C.; Wang, H. The effect of host–guest interaction in tourist co-creation in public services: Evidence from Hangzhou. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J.; Eusébio, C. Diverse socializing patterns in rural tourist experiences-a segmentation analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Almeida, N.; Marôco, J.; Santos-Pavón, E. Wine tourist profiling in the Porto wine cellars: Segmentation based on wine product involvement. Anatolia 2020, 31, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jollife, L.; Piboonrungroj, P. The role of themes and stories in tourism experiences. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Experience Management and Marketing; Dixit, S.K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 218–228. [Google Scholar]

- Mossberg, L. Extraordinary Experiences through Storytelling. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 8, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, D.; Nunes, M.; Liberato, P. Wine and Food Tourism Gamification. Exploratory Study in Peso da Régua. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems; ICOTTS 2020. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Abreu, D., Liberato, E.A., González, J.C., Ojeda, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 208, pp. 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Woodside, A. Storytelling research on international visitors Interpreting own experiences in Tokyo. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2011, 14, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moina, S.; Hosanyb, S.; O’Brien, J. Storytelling in destination brands’ promotional videos. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.; Foss, L. Coping and Co-creating in Tourist Experiences. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota da Bairrada. Quem Somos. Available online: http://www.rotadabairrada.pt/quemsomos/?id=3&title=quem-somos&idioma=pt (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Infovini. O portal do vinho Português. Available online: https://infovini.pt (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Pordata. Base de Dados Portugal Contemporâneo. 2021. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/Municipios/Capacidade+nos+alojamentos+tur%c3%adsticos+total+e+por+tipo+de+alojamento-747 (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Pordata. Base de dados Portugal Contemporâneo. 2019. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/Municipios/Dormidas+nos+alojamentos+tur%c3%adsticos+por+100+habitantes-761 (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Centre of Portugal. Mata do Buçaco. 2021. Available online: https://www.centerofportugal.com/pt/poi/a-mata-do-bucaco/ (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Yin, R. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, J.; Wallen, N.; Hyun, H. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education, 8th ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P.; Ness, L. Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research & Evolution Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martinho, V. Contributions from Literature for Understanding Wine Marketing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.; Price, L. River Magic: Extraordinary Experience and the Extended Service Encounter. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, T.; Kirova, V. Wine tourism experience: A netnography study. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.J.; Lima, J.; Silva, A. Landscape and the rural tourism experience: Identifying key elements, addressing potential, and implications for the future. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1217–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Residence | Visitor | Travel Group | Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | 7 | Tourist | 14 | Family and friends | 21 | Female | 15 |

| Foreign | 15 | Excursionist | 8 | Individual | 1 | Male | 7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carvalho, M.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. Interaction as a Central Element of Co-Creative Wine Tourism Experiences—Evidence from Bairrada, a Portuguese Wine-Producing Region. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169374

Carvalho M, Kastenholz E, Carneiro MJ. Interaction as a Central Element of Co-Creative Wine Tourism Experiences—Evidence from Bairrada, a Portuguese Wine-Producing Region. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):9374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169374

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarvalho, Mariana, Elisabeth Kastenholz, and Maria João Carneiro. 2021. "Interaction as a Central Element of Co-Creative Wine Tourism Experiences—Evidence from Bairrada, a Portuguese Wine-Producing Region" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 9374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169374

APA StyleCarvalho, M., Kastenholz, E., & Carneiro, M. J. (2021). Interaction as a Central Element of Co-Creative Wine Tourism Experiences—Evidence from Bairrada, a Portuguese Wine-Producing Region. Sustainability, 13(16), 9374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169374