1. Introduction

Cities worldwide, responding to massive challenges driven by population growth and climate change, have adopted smart city strategies, many of which are underpinned by conceptualizations that prescribe collaborations [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Collaboration was found by Meijer and Bolívar [

6] to be the dominant strategy in models of governance proposed in smart city literature. Smart city conceptualizations of collaboration focus on entire city ecosystems, relationships between city government and organizations from all sectors, and relationships between government and citizens. Even the relationship between units within a city administration is said to be more effective with smart city collaboration [

7,

8]. The wider public management literature [

9,

10,

11] has chronicled examples of the term collaboration being used interchangeably with cooperation and coordination, misleading stakeholders and exemplifying government rhetoric [

9]. Is smart city collaboration rhetoric or, can smart city theory extend public management theory?

To answer this question, our research sought to assemble the knowledge as to collaboration dispersed throughout the theoretical literature of numerous disciplines and explored the experience of authentic collaboration in an exemplary smart city. We applied the systematic literature review database search process to gather smart city collaboration articles from the numerous literature that report smart city research. For the theory strand and practice strand of our research, we created a tentative Smart City Collaboration Framework (SCCF) of five categories of relationships. To understand whether relationships were indeed collaboration, we applied the attributes of authentic collaboration determined by Keast et al. [

9]. We applied the SCCF and authentic collaboration attributes to theory and then applied the resultant tightly categorized conceptualizations to the evidence regarding the experiences of smart city Amsterdam. Amsterdam was chosen because it has been awarded for its achievement in the smart city domain and presents an adequate body of peer-reviewed information. We then iteratively interrogated the combined evidence to build knowledge to satisfy the following questions:

Our research brought clarity to smart city theory as to the role of collaboration, extending theory by categorizing collaboration according to the actors involved. Theory has been reinforced by our confirmation of most smart city conceptualizations of collaborative relationships as portraying authentic collaboration. However, we assert that further development of theory as to the collaborative relationship between city governments and citizens is required. Smart city theorists and practitioners are assisted in their efforts to build more effective smart city prescriptions and practices, and the sustainability of smart city collaboration has been established as a high priority for future research.

This paper has five further sections. The first is an explanation of the research methods. The second is a review that separates the smart city theory and conceptualizations of collaboration according to the SCCF. The third presents the evidence as to actual collaborative practice in Amsterdam. The fourth summarizes the findings and discusses the role of collaboration in a smart city, the efficacy of the SCCF conceptualization, and the factors affecting collaboration in a smart city. Finally, we present conclusions as to the role of collaboration in achieving smart city objectives and present proposals as to future research.

2. Research Approach

An exploratory full-text search of ProQuest Central for articles containing smart city and collaboration found 19,000 plus items from many disciplines. Undaunted, we applied a systematic literature review method with narrower search terms to identify all possible evidence as to smart city collaboration theory and then sought all available evidence as to smart city practice in the case study city, Amsterdam, through a combination of methods.

2.1. Smart City Collaboration Theory Search

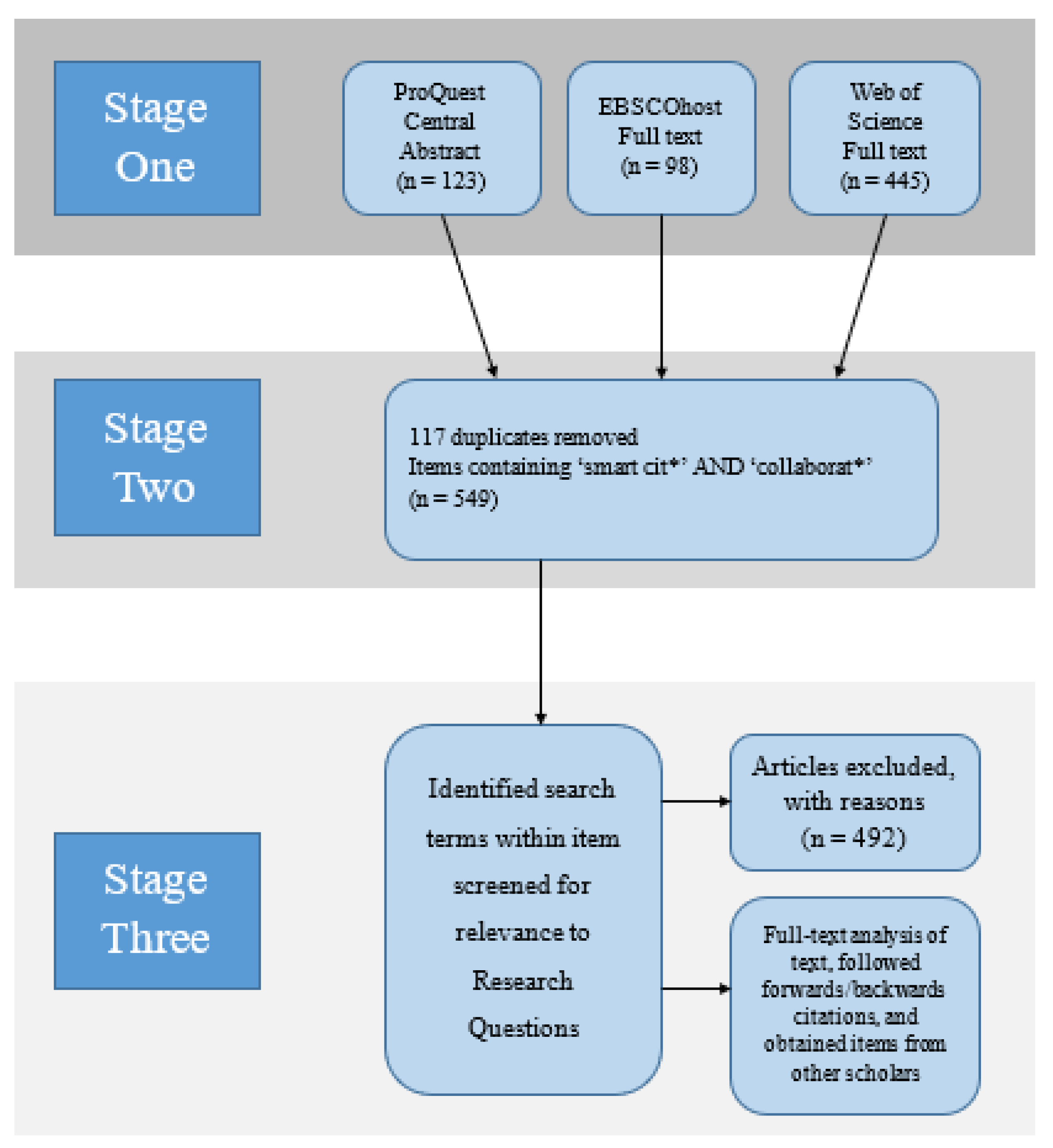

We followed the PRISMA process [

12] for database searching, commencing with searches of the Web of Science (Core Collection), ProQuest Central, and EBSCOhost (Academic Search Premier) databases. The search was limited to peer-reviewed items published in English from 1999 to 2020, as Meijer and Bolívar [

6] report the first smart city governance item they found was published in 1999. The terms ‘smart cit*’ AND ‘collaborat*’ were applied. We did not apply synonyms, as our research was tightly focused upon the use of the term collaboration.

Searching multiple publishers’ databases, full texts in the instances of Web of Science and EBSCOhost and abstracts in the case of ProQuest Central, identified a total of 666 items. We worked through these items in the stages set out in

Figure 1 (‘Literature identification process: smart city collaboration), finding that the vast majority of usages of ‘collaboration’ were incidental and of no assistance to our research. Ultimately, 57 offered potential for contribution to the research.

2.2. Smart City Collaboration Practice Search

The search for evidence as to the practice of smart city collaboration commenced during the theory search, allowing us to collate a list of items that reported case studies of smart cities.

Amsterdam was prominent, offering the strongest possibility of an adequate body of evidence that had been subjected to peer review and which extended over a period suitable for a longitudinal study. A further ‘smart city’ AND ‘Amsterdam’ search of the three databases was performed, resulting in 16 items specific to Amsterdam.

For both the theory and Amsterdam practice searches, additional items were identified by following forward and backward citations and by soliciting suggestions from scholars worldwide. We reached a saturation of sources.

Our research relies on 49 items. The spread of items is wide. Whilst only five came from publications specifically targeted at cities or smart cities, 16 items were drawn from the fields of information, information technology, or e-government. The public management field contributed 13 items, targeted at either the smart city or collaboration.

2.3. Analysis of Evidence

The analysis of the data from theoretical items preceded and informed the search of the validating evidence as to practice in Amsterdam, which, in turn, led to revisiting smart city collaboration theory. The dominant theme that emerged in the theory literature was the diverse combinations of actors involved in the prescribed collaborative relationships. So that the nuances between the assertions of different theorists as to the same combination of actors and the differences between combinations of actors could be highlighted, we formed the SCCF of categories of relationships, which are explicated in

Section 3.4 (‘With Whom Do We Collaborate?’) and applied in

Section 4 (‘Practice—Smart City Collaboration’).

3. Theory—Smart City Collaboration

3.1. Why We Collaborate

Collaboration involving multiple actors from all sectors is utilized by governments when faced with a problem that has not been resolved through traditional hierarchical relationships [

13] because collaboration enhances problem-solving capacity and achieves efficiency and effectiveness [

14,

15]. Yet, governments are circumspect as to involvement in cross-sector collaborations because the collaborations take decisions beyond the view of elected officials and are not accountable to the voters [

15]. Further, the word collaboration has been used interchangeably with other integration terms, namely communication [

10], coordination, and cooperation [

9], causing confusion as to intentions.

3.2. What Is Collaboration?

A hierarchy of levels of relationships between governments, service providers, and citizens was formed by Konrad [

10], commencing with independent operations, moving upwards to information sharing and communication, then cooperation, coordination, collaboration, and, finally, consolidation, where the organizations merge into a new, single entity. Keast et al. [

9] found substantial undifferentiated use of the words cooperation, coordination, and collaboration in the human services sector, and that 40% of government informants experienced dissonance between their personal understanding of the terms and the way in which the terms were used by governments. Precisely 86% of community sector representatives identified a disconnect between government policy statements involving the term collaboration and actual practice and community expectations [

9]. The continuation of undifferentiated usage was judged by Keast et al. [

9] to be motivated by a need by government informants to comply with then-current themes within the public sector, “The use of rhetoric over meaning by government […]”. The informants advised that despite the assertions of governments that they wanted collaboration, it was mostly coordination that governments wanted [

9].

Our conundrum revolves around whether rhetoric is in play in smart city theory or whether smart city theorists and city governments are using the term collaboration authentically and can contribute to forming effective collaboration. To assess whether authentic collaboration is intended or has taken place, we applied the attributes of collaboration identified by Keast et al. [

9]:

Long-term perspective to the relationship;

Purpose to create an outcome not previously achievable;

Substantial integration achieving synergy between organizations;

Systems have been changed;

Tight links between actors;

Actors move outside traditional functional areas, possibly a new entity;

Highly interdependent, sharing of power.

The smart city literature has increasingly moved from a technology-led supply push to prescribing collaboration as a remedy to the complexity inherent in smart city challenges [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. After reviewing the literature, Nam and Pardo [

16] identified four criteria for smart government of smart cities, namely efficiency, effectiveness, transparency, and collaboration. Collaboration was conceptualized as involving the city government in intraorganizational collaboration, intersectorial interorganizational collaboration, and citizen–government collaboration [

16].

Smart city theorists [

1] adopt the definition of collaboration established by Harrison et al. [

17], in the context of e-government projects, namely: “collaboration—frequency or duration of activities in which more than one set of stakeholders share responsibility or authority for decisions about operation, policies, or actions of government.” This conceptualization of collaboration, emphasizing shared decision-making, is consistent with that of Keast et al. [

9].

Some smart city theorists do distinguish between collaboration and related concepts. Nam and Pardo [

18] use the terms collaboration and coordination in tandem, distinguishing as to meaning. Gil-Garcia et al. [

1] establish governance, engagement, and collaboration as one of 10 core components of the conceptualization of a smart city yet, within that component, carefully distinguish between collaboration and engagement with stakeholders.

3.3. How Do We Collaborate?

When introducing collaboration, Mora, Deakin, and Reid [

3] assert smart cities must address: whether the strategy is to be technology-led or holistic; whether the approach is to be top-down or bottom-up; whether there is to be a monodimensional or integrated intervention logic; and whether collaboration is to follow the double-, triple-, or quadruple-helix model.

The top-down approach requires city government to drive the strategy, applying incentives, funding, and publicity to facilitate a program of city government initiatives [

19]. In the bottom-up approach, planning involves stakeholders from all sectors, organizations, and individuals, creating cross-sectoral partnerships. City government must not only achieve strong stakeholder engagement in respect of city government initiatives but also bring proposals from the bottom up into the political arena, facilitating consensus-building [

19].

The double-helix model involves two actors, the city government and typically a smart city system vendor [

20,

21]. The triple-helix model of collaboration is formed of actors drawn from government, industry, and research institutions [

22]. The quadruple-helix model encompasses those sectors plus citizens and community organizations [

23]. Notwithstanding their prominence within the smart city literature, the helix models do not attempt to address the matter of collaboration internal to an organization.

3.4. With Whom Do We Collaborate?

Within these top-down/bottom-up and helix approaches, to achieve smart city objectives, there are diverse relationships between actors. To achieve clarity, we assembled the evidence from the smart city theory literature against the SCCF categories of relationships.

3.4.1. City Government Internal Collaboration

In the context of the smart city, Alhusban [

7] and Viale Pereira et al. [

8] identify the need for collaboration between units within public organizations as important to the implementation of an ICT-based smart governance approach, remedying a siloed approach, and achieving objectives.

Managers in four North American smart cities informed Alawadhi et al. [

24] that interdepartmental collaboration and cooperation had been essential for the success of smart city initiatives. Similarly, Pierce and Andersson [

25] interviewed 12 municipal administrators involved in smart city initiatives, finding that collaboration was their predominant challenge. Within the overall collaboration challenge, absence of internal cooperation was specified by 11 of the 12 informants as frustrating the achievement of initiatives [

25]. A compelling explanation is made by one of the informants from Rotterdam [

25] who said “[…] I have colleagues that are responsible for the street lighting […] for the sewer system or the parking lots […] have only one responsibility […] and everything that you want to combine […] connectivity to our street lighting or charging equipment for electronic vehicles […] you complicate their tasks […] it is not always easy to convince colleagues to co-operate […].”

Interorganizational collaboration goes beyond efficiency and effectiveness. Keast et al. [

9] were informed that governments that seek to develop collaboration with other sectors must accept that they are responsible for providing leadership as to collaboration, by example. The smart city context requires city governments to ‘walk the talk’ by way of cooperation and collaboration between its units and with other government organizations.

3.4.2. City Government and Other Government Organizations

Collaboration between municipalities and with other levels of government is essential to the achievement of smart city objectives. Many cities comprise multiple local governments, reflecting the sprawl of the town into surrounding local government areas. Higher levels of government enter the mix, typically creating organizations to provide health, education, transport, and water services across multiple municipalities, and thus having purposes and objectives that are not focused on a sole municipality.

Capacity to manage across geographical or jurisdictional boundaries is key to the achievement of smart city objectives [

7,

8]. Pardo, Gil-Garcia, and Luna-Reyes [

26] identified collaborative capacity as essential to the success of organizations in establishing effective information sharing across the boundaries of organizations.

3.4.3. City Government and Organizations

Mainstream to the smart city conceptualization of collaboration is the relationship between the city government and nongovernmental parties, such as companies, not-for-profit organizations, and civic groups [

8]. Smart city collaborative interorganizational configurations have been influenced by those found to be successful in digital government projects [

27], ranging from quasi-markets and Public and Private Partnerships (PPPs), to public procurement, to project financing, and to innovative forms based on the active engagement of citizens [

28].

A significant innovative form is the Urban Living Lab (ULL), which is authentic collaboration, taking a real-life environment, being managed by the municipality in collaboration with civil society organizations or research centers, and being where citizens, experts, and private companies codesign, coproduce, and test services intended for the whole city [

28].

3.4.4. City Government, Organizations, and Citizens

Citizens were added as the fourth helix [

23] to emphasize the importance of citizens to achieving social and economic benefits through collaboration [

29]. Conceptual models of smart city governance take a citizen-centric approach [

30,

31,

32]. The citizen is to be the focus of collaboration between city government and external organizations and citizens, not only to achieve increased efficiency, effectiveness, and transparency but also to facilitate nongovernment entities’ participation in decision-making [

16].

This high level of conceptualization does not inform the reader as to the configuration of, or characteristics of, the relationship between the citizen and city government, leaving unanswered the question of whether it is one of collaboration, cooperation, consultation, or communication.

At a lower, transactional level, smart cities are said to be achieving collaborative governance when there is citizen involvement in public affairs, through transparency websites, open data platforms or e-participation platforms [

33], or social media [

2]. Having regard to the findings of Keast et al. [

9] that governments assert that they want collaboration but mostly want coordination that governments wanted [

9], we were concerned as to whether authentic collaboration is taking place through these ICT-based channels. Zavattaro and Brainard [

34] designate smart city social media microencounters between citizens and their governments as collaboration, which provide city government with a chance to interact with someone to share information, to crowdsource ideas, to find policy ideas, and to be part of evidence-based decision-making. None of that explanation meets the attributes of authentic collaboration set by Keast et al. [

9], by, for example, achieving a long-term perspective to the relationship, substantial integration of activities, synergy, tight links, and interdependence.

Other theorists distinguish collaboration from other relationships between city governments and citizens. For Yerden, Gasco-Hernandez, Gil-Garcia, Burke, and Figueroa [

35], smartness of a city has four dimensions, two of which are ‘Citizen Participation’ and ‘Community and Stakeholder Engagement’. The authors situate collaboration within the Community and Stakeholder Engagement dimension, suggesting the possibility of a perspective that citizen participation does not primarily require collaboration, but that collaboration is but one of the options as to city government engagement of stakeholders (including the community).

Put another way, no assumption should be made that citizen participation requires collaboration. Stakeholder engagement relationships other than collaboration may accurately describe the intended interaction between city government and citizens.

3.4.5. Organizations and Citizens without City Government

Smart city theory conceptualizes city government not only as an actor in collaborations but also as responsible for both inciting others to respond to smart city challenges and for creating an environment that encourages others to collaborate.

The concept of governance without government was identified by Gil-Garcia et al. [

1] as a distinct strand of literature where stakeholders, advocates, civil groups, and individual citizens are depicted as integrating to form a governance mechanism, which does not include government. This smart city conceptualization is consistent with Klijn and Koppenjan’s [

36] authoritative definition of governance networks as “[…] social relations between mutually dependent actors […]”. Similarly, innovative governance networks may be based on a collaborative relationship not involving government [

37].

Whilst the government may not be an actor within the collaboration, smart city literature conceptualizes the city as accentuating the participation of citizens, organizations, and industry to attract human capital, which is then mobilized in collaborations to achieve the city’s objectives [

6]. The city government’s role is to facilitate networks, which collaborate to produce innovations that benefit the city. This is a strategy in itself, one where the city government develops a collaborative environment [

38].

Put another way, city government is required both to develop a collaborative ecosystem, including the inherent bottom-up processes, and to coordinate the efforts of the collaborating actors towards shared smart city objectives [

3].

4. Practice—Smart City Collaboration

To clarify many of the claims of smart city theory about collaboration, we examined evidence as to the experience of an exemplar smart city, Amsterdam.

4.1. Amsterdam the Smart City

Amsterdam has taken a political decision to adopt a holistic smart city strategy [

3] that nurtures both ITC and no-tech initiatives to pursue objectives through the Amsterdam Smart City (ASC) program [

39]. Explanation of the wider context in which the formal ASC program is situated will assist our understanding of the structure of actors and the actual role of collaboration in achieving the ASC program objectives.

Amsterdam municipality has a population of 820,000 [

40] and is one of the 32 municipalities that comprise the greater Amsterdam Metropolitan Area (AMA), which has a population of 2.5 m [

41]. The AMA is the focus of the ASC program [

42]. ASC is a nongovernment entity, a foundation, self-described as part of the Amsterdam Economic Board (AEB) [

43].

In 2007, the ASC concept emerged from collaboration between the Municipality of Amsterdam, the Amsterdam Innovation Motor (AIM) and energy network operator, Liander [

21]. Members of the AIM were major banks, two universities, the municipalities of Amsterdam and Almere, and the Province of Noord-Holland. The three organizations that founded the ASC provided strong leadership and resourcing, guiding the progressive development of the Amsterdam Smart City strategy, stakeholder communication, and promotion and establishing the procedures and processes for the selection and execution of projects before launching the ASC program [

21]. Key to the refinement of the strategy was extensive, extended consultation with organizations having shared interests in addressing pollution, energy consumption, and environmental quality, for the purposes of aligning the overall strategy to European, national, and municipal levels, identifying funding sources and informing the choice of projects.

In 2009, the ASC was launched with five founding partners, namely the Municipality of Amsterdam, AIM (to later become the AEB), Gemeente Amsterdam, KPN, and Liander [

39]. The ASC secretariat of 11 persons is funded by the Municipality of Amsterdam.

In 2013, the ASC launched the current online Amsterdam Smart City Platform [

44], self-described as a meeting place for companies, knowledge institutions, governments, and active residents to interact and collaborate for the city and region of the future [

42].

In 2020, the ASC had a governance board of 20 permanent partners, comprising local governments, for-profit companies, government organizations, and social organizations [

42], but not citizen organizations. These partners, who are separate from the project partners, contribute resources and interact towards the complex city challenges [

44].

The challenges facing greater Amsterdam are: making the switch from fossil to sustainable energy, turning waste into raw materials, switching to clean transport, and keeping Amsterdam’s digital world transparent [

42]. ASC explains that the “[…] partners are convinced that the necessary changes for the city and region to move forward, can only be achieved through collaboration” [

42]. The ASC facilitates 200 plus public, private for-profit, and not-for-profit organizations in more than 270 projects [

28]. To extract learnings from greater Amsterdam’s 20-year journey, we will now examine the evidence through the lens of the framework of categories of relationships.

4.2. City Government Internal Collaboration

The combined AEB and ASC governance arrangements are situated outside the organizational structures of the municipal governments. No reorganization of existing organizational structures has been reported. The exception is the creation of the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) within the Municipality of Amsterdam in 2014 with the brief to follow technological developments and to apply technology to reach the municipality’s objectives [

44]. The CTO does act as a partner in specific projects and “[…] works against the silos of the municipal bureaucracy […] organizing smart coalitions to solve them […]” [

44].

The municipalities have established an authentic collaboration in the form of the AEB/ASC, taking a long-term focus and working intensely with a small, restricted number of stakeholders to resource and form a new, additional entity. Yet, the municipalities do not appear to have applied theoretical prescriptions as to smart city collaboration [

7,

8] to internal units. Regarding the Municipality of Amsterdam, an informant advised [

38] that “the Board (ASC) was created to improve coordination among departments” and that the decision to locate the governance structure outside the municipality was influenced by there being existing external entities.

There was no further evidence to allow our research to proceed further with the intriguing question as to why, in practice, municipalities did not also take up a strategy based upon internal collaboration. This topic is highly important, not only to the success of the work of the municipality but also to the preparedness of other stakeholders to collaborate. A multinational company informant put their position as “We want to make sure that we work on a project that has the support from the city as a whole, not only one department … city administrations have to think about how to organize themselves.” [

44].

4.3. City Government and Other Government Organizations

The AEB board of 25 members contains four municipality representatives and one province representative [

45]. Amongst the 20 ASC partners, there are three municipalities, and one regional government representative, the Amsterdam Transport Region [

42]. There is no national-level government member of the AEB/ASC mechanism.

National government is involved in ASC projects by invitation. Examples are the Ministry of Economic Affairs and the Ministry of Infrastructure, which partner in a behavioral change towards plastics project, and the Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment and Ministry of Economic Affairs in the Fair Meter development project [

44]. The Ministries did not initiate the collaboration but were invited to join as a need presented.

4.4. City Government and Organizations

The AEB/ASC top-down arrangements are an authentic collaboration between local governments, companies and utilities, and, to a lesser extent, knowledge institutions and social organizations.

At the project level, there is broader diversity of participants extending to small businesses, departments of municipal governments and local citizens, and professional and business groups. Of the 12 projects chosen by van Winden et al. [

44], 10 displayed the Keast et al. [

9] attributes of authentic collaboration.

These examples suffered the difficulties inherent in collaborations. The AEB in 2014 (AEB cited in [

21]) signaled difficulties involved in “[…] the stimulation and support of sustainable collaboration […]” as a key challenge to strengthening the economy of the AMA. Maintaining collaborative relationships has proved difficult in the public sector [

46,

47,

48,

49] and the private sector [

50,

51]. We identified the following themes of factors that impacted the success of the ASC project collaborations.

4.4.1. Funding Source

The proliferation of smart city technology projects in the ASC program has been attributed [

44] to the willingness of stakeholders to innovate and the substantial local, national, and EU funding. Dameri [

39] connects the boom in smart city initiatives after 2009 with substantial EU funding aimed at CO

2 emissions, energy consumption, waste treatment, and building efficiency.

Yet, van Winden et al. [

44] suggest that external funding and associated publicity may lead to collaborative relationships being established that do not develop the attributes necessary for longevity and success. Van Winden et al. [

44] reported the software project, which was to match the supply of renewable energy with the demand for a municipality’s vehicles. Subsidized with EU funds, the municipality in 2010 partnered with a for-profit technology provider to design the IT to affect the supply/demand matching. The 2013 pilot was acclaimed but ended in a year. The EU subsidy had ended, and the municipality withdrew funding and support [

44].

This example highlights the importance of the source of the funding as the risk is that external funding may not secure the long-term commitment of key collaboration members, resulting in collaboration members being vulnerable to the actions of others. Another example is a project that had a loosely defined objective of making a retail precinct sustainable and ended after the completion of the pilot when the municipality withdrew funding. Van Winden et al. [

44] attributed the project’s demise to the lack of benefits for key stakeholders, specifically the retailers, and the lack of ownership of the objectives by any member.

4.4.2. Lack of Ownership of Project

Ownership in the smart city project context is seen by van Winden et al. [

44] as evidenced by the project partners agreeing that the project is valuable and committing resources (cofinancing, charging for products or services at cost, or committing human resources). This perception as to value must be real to the project partner. They cite the sustainable retail precinct project, observing that there was no benefit to the retailers to install the technology as savings either accrued to the property owner or were marginal, causing the retailers to lose connection with the project.

Van Winden et al. [

44] found that success of the project was associated with one partner having a clear future benefit from the project. They named six projects that all had a private partner in the lead that invested in the project and displayed responsibility for making it a success [

44]. In other projects, the ownership of the project had been shared, making it harder to manage.

After the van Winden et al. [

44] evaluation of project collaborations, Neuroni et al. [

52] reported that the city administration had gradually changed from being a project initiator and lead to being a facilitator of the smart city community. The reasons were: significant resource costs for project management and lack of ownership of problems by project partners.

4.4.3. A Leader of the Project

Having a partner that will clearly benefit from the project [

44] is linked to the need for a highly committed person as project leader. In the sustainable retail precinct project, a consultancy was appointed to ‘run the project’, which had eight project partners and 40 entrepreneurs, plus a manager was appointed to work with entrepreneurs. The project almost collapsed due to lack of clarity as to who was in charge and lack of commitment.

Successful projects had a project leader, from one of the project partners, who had the power, interest, and incentives to overcome difficulties and the competence to manage a multistakeholder team [

44]. This perspective is given less weight than the importance of the role of the overall leader of smart city project delivery, the chief digital or technology officer, the equivalent to that of Amsterdam, Chief Technology Officer. Sancino and Hudson [

53] examined the forms of leadership applied in smart city innovation projects in Amsterdam, Bristol, Milton Keynes, Chicago, Curitiba, and Melbourne. Whilst having regard to the evidence of van Winden et al. [

44], Sancino and Hudson [

53] concluded that persons holding the Chief Technology position were pivotal to the success of the other actors, including the leaders of individual projects.

4.5. City Government, Organizations, and Citizens

The AEB explains its purpose as increasing the prosperity and well-being in the AMA through innovation and collaboration between the private sector, knowledge institutes, and government organizations [

45]. Citizens are not included in the envisaged collaboration of the AEB board. It is the ASC framework that provides the possibility of citizens being involved in collaboration targeted at smart city objectives. We examined the experience of citizens, first within the governance board of the ASC and then in the projects.

4.5.1. Overall ASC Governance

The ASC Board [

42] has no citizen representative organizations as members, other than the local governments. Sancino and Hudson [

53] found that the ASC is a formal public–private partnership that brings together partners from business, the local municipalities, and knowledge institutions and coordinates other organizations and citizens in projects. ASC level decision-making is available only to selected groups, such as public entities, firms, associations, and experts, with citizens having the opportunity to engage and possibly collaborate only through the projects [

53] and then mostly online [

28]. This restriction of the oversight decision-making to only privileged groups does not satisfy the smart city conceptualization of smart city governance as establishing an open, inclusive, and engaging collaborative environment [

3]. The restriction appears to be interwoven with the permanent partner eligibility requirement to contribute resources [

44].

4.5.2. Governance of Individual Projects

At the individual project level, citizens and citizen groups are provided with a bottom-up process for proposing and participating in innovation projects, but there is evidence that, in practice, the ASC approval and project management requirements restrict citizen participation in ASC projects. Citizens can propose initiatives and invite others to participate [

44]. For initiatives to become ASC projects, ASC requirements are applied by permanent partners who are keenly focused on ensuring the success of each project right through to scaling up in implementation. Project partners must agree to the initial partnership and the addition of further partners as the project evolves.

An open and inclusive environment, to the point of a proposal being considered by the ASC, is achieved. However, the subsequent decision-making processes, applying criteria crafted to achieve long-term viability, are problematical to those examining the ASC practice through a citizen participation lens. Van Winden et al. [

44] challenged the implications of policies, using the successful Smart Light project as an example. All project partners were ASC permanent partners, causing van Winden et al. [

44] to question whether start-ups, other companies, and knowledge institutes have a chance to collaborate. After examining the 11 other projects they observed that while many ASC projects say citizens are central to their purpose, there is rarely evidence of this, and citizens are seldom included as an official part of the project partnership [

44].

Citizen participation in ASC activities continues to be problematical. Sancino and Hudson [

53] concluded that ASC arrangements had weaknesses in citizen engagement in projects and citizens were often not part of project governance. Nesti and Graziano [

38] concluded that the AEB/ASC arrangement strongly promotes economic development and inhibits citizens’ participation. The exception appears to be the projects which were configured to the Urban Living Lab (ULL) format in which Nesti [

28] found citizens were actively involved in a collaborative relationship.

4.6. Organizations and Citizens without City Government

The AEB/ASC initiative has attracted collaborations between stakeholders that satisfy the governance-without-government model [

1]. Indeed, only three of the twelve projects examined by van Winden et al. [

44] involved government, with nine involving only private companies, NGOs, and local groups. Such collaboration between a wide range of stakeholders without government is conceptualized by van Winden et al. [

44] as being an element of a collaborative ecosystem. The AEB and ASC have been acknowledged as engendering or enhancing the capacity of organizations and citizens for collaboration and establishing a strong collaborative ecosystem around the shared challenges [

3,

44].

What was not clear was whether this collaborative ecosystem is limited to the AEB/ASC projects or whether it refers to the whole AMA. A broad model of the collaborative ecosystem would be consistent with the vision of Meijer and Bolívar [

6] of the smart city as attracting human capital and of the city government as being required to provide bottom-up processes to steer collaborations towards the city’s objectives [

3].

Van Winden et al. [

44] describe the collaborative ecosystem as requiring the “[…] right ecosystem of partners, organizing the process, and creating commitment and shared value amongst partners with varying interests […]”. In the greater Amsterdam context, Mora et al. [

3] described the collaborative ecosystem of Amsterdam as comprising large communities that are continually growing larger due to the activity of the city governments, AEB and ASC. Proceeding wider, Nesti and Graziano [

38] describe smart cities as being designed as open ecosystems in which stakeholders ranging from politicians through organizations to citizens interact to produce local innovation, suggesting a city-wide model for an ecosystem, possibly a collaborative ecosystem. The practice in greater Amsterdam has been examined by van Winden et al. [

44] and Neuroni et al. [

52], of which van Winden is one of the authors. Neuroni et al. [

52] evaluated the public value created by Amsterdam explaining the Amsterdam area as an innovation ecosystem and nesting within that ecosystem the AEB/ASC-based smart city ecosystem, which they describe as the collaborative ecosystem.

5. Discussion

Our approach of assembling smart city knowledge around the SCCF of typical relationships, then applying this to the experience of an exemplar smart city, brought clarity to aspects of theory and highlighted one model of smart city collaboration strategy in practice. Amsterdam’s experience provided an explanation of factors that impacted collaborations. We first discuss the role of collaboration in a smart city. Second, we examine the efficacy of the SCCF for research into smart city collaboration. Finally, we discuss the implications of factors impacting collaboration.

5.1. The Role of Collaboration in a Smart City

We find that the advocacy of the smart city literature for the adoption of collaboration as a strategy to achieve smart city objectives is apposite and supported by a broad range of literature and the Amsterdam experience. However, practice and the application of widely accepted attributes of authentic collaboration established by Keast et al. [

9] revealed aspects of smart city collaboration conceptualizations that are problematical or require further development. Our findings are summarized in

Table 1 (‘Findings as to smart city collaboration theory and practice’). We now justify our conclusions and explore the key implications of the evidence.

The conceptualization of collaboration [

25] within a city government as being required to achieve smart city objectives [

7,

8] was confirmed by evidence from the Municipality of Amsterdam. There was evidence that the Amsterdam Smart City (ASC) arrangements were created to improve coordination between departments [

28] and that the Office of the Chief Technology Officer was created to work against the silos within the city administration [

44].

This limited change to internal organizational arrangements is intriguingly contrary to the smart city prescription of collaboration [

7,

8] and the introduction of new organizational arrangements [

28]. Smart city theory has yet to explore whether, and why, organizational units within city administrations are active (or not) in internal and external smart city collaborations. The evidence from a private partner informant was that prospective private partners required assurance that there was collaboration within the city administration as a whole so that the project was fully supported [

44]. It follows then that elected officials and city administrators would value knowledge that would better equip them to address the reputed siloed behavior and apply city resources directly to the smart city objectives.

Collaboration between levels of government as a remedy for issues arising from geographical and jurisdictional boundaries is fundamental to smart city conceptualizations. Such intergovernmental collaboration was evident in Amsterdam in the collaboration between local governments and bottom-up approach to the involvement of other levels of government.

Collaboration [

1,

7,

8] between city government and companies, nonprofit organizations, and civic groups is core to smart city literature [

8,

27,

28] and was demonstrated to be necessary to the achievement of smart city objectives by the Amsterdam evidence.

The conceptualizations of collaboration between city government and citizens as advocated by some smart city theorists [

29,

30,

31,

32] are problematical in that they do not specify the practical detail of the actual envisaged relationship. Our application of the general public management attributes of collaboration specified by Keast et al. [

9] revealed that the smart city conceptualizations of collaboration by city government with citizens are highly unlikely to be collaboration. The exception is the ULL model [

28]. We find that smart city theory as to collaboration between city government and citizens is underdeveloped, requiring a greater explanation of the bidirectional relationship between citizen and government. Pending further explanation of conceptualizations of collaboration involving citizens, we suggest that scholars proceed on the basis that citizen participation does not necessarily require collaboration and that usage of the term collaboration may well be an artifact of government rhetoric [

9] that obscures an intent to communicate, consult, cooperate, or coordinate.

Collaboration without city government in the relationship, but between all parties involved in a project [

1,

6], was confirmed to be essential to the achievement of smart city objectives. Importantly, the responsibility of the city government both for the development of an open, collaborative environment for stakeholders [

38] and for the coordination of the collaborating parties towards shared smart city goals [

3] was confirmed by the Amsterdam example.

The scope of the collaborative environment is conceptualized as city wide [

3,

38], but the Amsterdam evidence was that a collaborative ecosystem surrounded the AEB/ASC institutional arrangements and was nested within the innovative ecosystem of the entire city [

44,

52]. We recommend that theorists and practitioners adopt a similar distinction.

5.2. Efficacy of Smart City Collaboration Framework

The SCCF applied throughout this study has clarified the participants in the purported collaborations. It has facilitated the application of the Keast et al. [

9] attributes of collaboration to determine whether the conceptualization or actual practice was indeed authentic collaboration or perhaps another relationship such as consultation, cooperation, or coordination, or merely communication.

We suggest that smart city governance theory be extended by the adoption of the attributes of collaboration established by Keast et al. [

9] in all conceptualizations of collaborative relationships. The resultant clarity as to meaning would assist governments and practitioners to better communicate their intended meaning and reduce the confusion, disappointment on the part of organizations and citizens, and allegations of government rhetoric.

Similarly, the SCCF will assist to better order smart city collaboration theory, facilitating the work of theorists and practitioners. The framework offers the capacity for adjustment to meet the needs of research. An example would be the unpacking of ‘City government and organizations’ to distinguish between companies and, say, utilities.

5.3. Factors Impacting Collaboration in a Smart City

Evidence as to factors impacting collaboration was captured incidental to our main focus, yet we knew that collaboration presents challenges that must be met. In the wider public sector, Keast et al. [

9] found that collaboration is time consuming, is a more intense, resource-hungry relationship, and that there is a tendency for the collaboration to fail or to revert to cooperation. Here we discuss the implications of the available evidence as to the factors and justify future research into the crucial emerging area of sustainability of smart city collaboration.

Funding source, and the propensity for its withdrawal, is highly likely to lead to the initiative not achieving objectives [

44]. One example involved a municipality that ceased support when EU subsidy ended leaving the for-profit technology provider partner without the expected marketable product envisaged in the original collaboration. A second was a municipality that ceased funding at the completion of the pilot phase because of the lack of ownership of the objectives by any significant member, including itself.

This risk to the collaboration of funding being withdrawn relates directly to the problem caused by collaboration members not having ownership because they have not invested resources in the project. Van Winden et al. [

44] observed that the success of an ASC project was accompanied by there being one partner organization that could clearly benefit from the project and that, having invested funding and resources in the project, felt responsible to make it a success. Ownership of the project by that invested organization was linked to there being a highly committed person as project leader, ideally from that organization, and possessing competencies suitable to the challenge of multistakeholder collaboration [

44].

This jumble of interconnected factors signposts an area where smart city theorists and practitioners have been signaling difficulty. The smart urban collaboration model of the smart city requires a high level of transformation [

6]. The AEB summed up the problem and need as “[…] the stimulation and support of sustainable collaboration …” (AEB cited in [

21], p 256). Substantial problems with sustaining collaborative relationships have been the experience with collaborations centered on the public sector [

46,

47,

48,

49] and the private sector [

50,

51]. Research aimed at understanding the barriers to sustained collaboration in smart cities would benefit a range of smart city stakeholders.

6. Conclusions

Collaboration was demonstrated to be the form of relationship that in theory and in practice offers the possibility of meeting the substantial smart city challenges, namely climate change, environmental pollution, globalization, and financial crises [

28]. Our research dug deeply into a fundamental concern engendered by the promises of smart city literature, namely what do smart city theorists and practitioners mean when they invoke the word collaboration?

We reinforced smart city theory by confirming most smart city conceptualizations of collaborative relationships and identifying the need for research that develops smart theory as to the role of collaborative relationships between city governments and citizens, particularly unpacking the nuances of intentions to collaborate, consult, and communicate.

Smart city theory as to collaboration at all levels was made clearer by our introduction of the Smart City Collaboration Framework of typical relationships between parties. In addition, smart city theory has been strengthened by the integration of the attributes of collaboration in public management developed by Keast et al. [

9]. The addition to smart theory of the SCCF framework and the attributes of collaboration will assist theorists and practitioners to build more effective smart city prescriptions and practice.

Research that will build on those enhancements to smart city theory and the lessons from the greater Amsterdam experience is necessary because there is limited knowledge as to factors that impact the sustainability of collaborations in a smart city. This presented as a significant stumbling block to the success of the Amsterdam smart city innovation projects. We propose a case-study-based body of research involving a number of smart cities, selected to provide counterfactual examples; an archival search; and the gathering of empirical evidence by interviews and surveys. A second, related area of needed research is knowledge as to the options as to organizational configurations that best support collaborative relationships and collaborative ecosystems. The unit of analysis would be the smart city as a whole, with particular regard being had to whether the vehicle for implementing the smart city strategy is internal or external to city administration. The resulting knowledge as to why city governments, including Amsterdam, chose their approach to achieving smart city objectives, through collaboration or not, will be highly beneficial to those cities embarking on their smart city journeys.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E.M. and I.I.; methodology, D.E.M.; validation, D.E.M., I.I., and S.G.P.; formal analysis, D.E.M., I.I., and S.G.P.; investigation, D.E.M.; analysis and development of argument, S.G.P.; knowledge, sources and analysis, D.E.M. and I.I.; writing—original draft preparation, D.E.M.; writing—review and editing, D.E.M., I.I., and S.G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Pardo, T.A.; Nam, T. What makes a city smart? Identifying core components and proposing an integrative and comprehensive conceptualization. Inf. Polity 2015, 20, 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Beyond information-sharing. A typology of government challenges and requirements for two-way social media communication with citizens. Electron. J. E Gov. 2018, 16, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, L.; Deakin, M.; Reid, A. Strategic principles for smart city development: A multiple case study analysis of European best practices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.V.; Parycek, P.; Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Smart governance in the context of smart cities: A literature review. Inf. Polity 2018, 23, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhlandt, R.W.S. The governance of smart cities: A systematic literature review. Cities 2018, 81, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A.; Bolívar, M.P.R. Governing the smart city: A review of the literature on smart urban governance. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2016, 82, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusban, M. The Practicality of Public Service Integration. Electron. J. E Gov. 2015, 13, 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.V.; Cunha, M.A.; Lampoltshammer, T.J.; Parycek, P.; Testa, M.G. Increasing collaboration and participation in smart city governance: A cross-case analysis of smart city initiatives. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2017, 23, 526–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keast, R.L.; Brown, K.A.; Mandell, M. Getting the right mix: Unpacking integration meanings and strategies. Int. Public Manag. J. 2007, 10, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, E.L. A multidimensional framework for conceptualizing human services integration initiatives. New Dir. Eval. 1996, 1996, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, M. Starting to untangle the web of cooperation, coordination, and collaboration: A framework for public managers. Int. J. Public Adm. 2012, 35, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryson, J.; Sancino, A.; Benington, J.; Sørensen, E. Towards a multi-actor theory of public value co-creation. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.; Entwistle, T. Does cross-sectoral partnership deliver? An empirical exploration of public service effectiveness, efficiency, and equity. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2010, 20, 679–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.B.; Stone, M.M.; Bryson, J.M.; Crosby, B.C. Public value creation by cross-sector collaborations: A framework and challenges of assessment. Public Adm. 2015, 93, 715–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. The changing face of a city government: A case study of Philly311. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.M.; Guerrero, S.; Burke, G.B.; Cook, M.; Cresswell, A.; Helbig, N.; Hrdinova, J.; Pardo, T. Open government and e-government: Democratic challenges from a public value perspective. Inf. Polity 2012, 17, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Understanding municipal service integration: An exploratory study of 311 contact centers. J. Urban Technol. 2014, 21, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeckman, C.; van der Graaf, S. The city as living labortory: A playground for the innovative development of smart city applications. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE), Bergamo, Italy, 23–25 June 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Leydesdorff, L.; Deakin, M. The triple-helix model of smart cities: A neo-evolutionary perspective. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Bolici, R. How to become a smart city: Learning from Amsterdam. In International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H. Innovation in innovation: The triple helix of university-industry-government relations. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2003, 42, 293–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F. Developed democracies versus emerging autocracies: Arts, democracy, and innovation in Quadruple Helix innovation systems. J. Innov. Entrep. 2014, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadhi, S.; Aldama-Nalda, A.; Chourabi, H.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Leung, S.; Mellouli, S.; Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J.; Walker, S. Building Understanding of Smart City Initiatives. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Government, Delft, The Netherlands, 3–6 September 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, P.; Andersson, B. Challenges with smart cities initiatives–A municipal decision makers’ perspective. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, T.A.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. Collaborative governance and cross-boundary information sharing: Envisioning a networked and IT-enabled public administration. In The Future of Public Administration around the World: The Minnowbrook Perspective; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Picazo-Vela, S.; Luna, D.E.; Gil-Garcia, J.R. Creating public value through digital government: Lessons on inter-organizational collaboration and information technologies. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; pp. 2840–2849. [Google Scholar]

- Nesti, G. Defining and assessing the transformational nature of smart city governance: Insights from four European cases. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2020, 86, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, M.; Mora, L.; Reid, A. The research and innovation of Smart Specialisation Strategies: The transition from the Triple to Quadruple Helix. In Proceedings of the Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings, Odessa, Ukraine, 21–22 June 2018; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency: Varazdin, Croatia, 2018; pp. 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Castelnovo, W.; Misuraca, G.; Savoldelli, A. Smart cities governance: The need for a holistic approach to assessing urban participatory policy making. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2016, 34, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameri, R.P. Searching for smart city definition: A comprehensive proposal. Int. J. Comput. Technol. 2013, 11, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Güell, J.-M.; Collado-Lara, M.; Guzmán-Araña, S.; Fernández-Añez, V. Incorporating a systemic and foresight approach into smart city initiatives: The case of Spanish cities. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bolivar, M.P.R. Creative citizenship: The new wave for collaborative environments in smart cities. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2018, 31, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavattaro, S.M.; Brainard, L.A. Social media as micro-encounters. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2019, 32, 562–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerden, X.; Gasco-Hernandez, M.; GilGarcia, J.R.; Burke, G.B.; Figueroa, M. Small Town vs. Big City: A Comparative Study on the Role of Public Libraries in the Development of Smart Communities. EGOV-CeDEM-ePart 2020, 2020, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn, E.-H.; Koppenjan, J. Complexity in governance network theory. Complex. Gov. Netw. 2014, 1, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Keast, R.; Mandell, M.P.; Brown, K.; Woolcock, G. Network structures: Working differently and changing expectations. Public Adm. Rev. 2004, 64, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesti, G.; Graziano, P.R. The democratic anchorage of governance networks in smart cities: An empirical assessment. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 648–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameri, R.P. Comparing smart and digital city: Initiatives and strategies in Amsterdam and Genoa. Are they digital and/or smart? In Smart City; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 45–88. [Google Scholar]

- Amsterdam. Info. Amsterdam. Available online: https://www.amsterdam.info/ (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- AEB. Who We Are. Available online: https://amsterdameconomicboard.com/wie-zijn-we#board (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- ASC. Project for You. Available online: https://amsterdamsmartcity.com/about (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- ASC. About Us. Available online: https://amsterdamsmartcity.com/about (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- van Winden, W.; Oskam, I.; van den Buuse, D.; Schrama, W.; van Dijck, E.J. Organising Smart City Projects: Lessons from Amsterdam; Lectoraat Urban Economic Innovation: Amsterdam, The Nertherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- AEB. About the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area. Available online: https://www.metropoolregioamsterdam.nl/over-mra/ (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Gray, B. Finding Common Ground for Multiparty Problems; The Josseybass Social Behavioral Science Series; Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1989; p. 658. [Google Scholar]

- Huxham, C.; Vangen, S. Managing to Collaborate: The Theory and Practice of Collaborative Advantage; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Keast, R. Joined-up governance in Australia: How the past can inform the future. Int. J. Public Adm. 2011, 34, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keast, R. Shining a Light on the Black Box of Collaboration: Mapping the prerequisites for cross-sector working. In The Three Sector Solution: Delivering Public Policy in Collaboration with Not-Forprofits and Business; Butcher, J., Gilchrist, D., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2016; pp. 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Boughzala, I.; De Vreede, G.-J. Evaluating team collaboration quality: The development and field application of a collaboration maturity model. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 32, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Van Dissel, H.G. Sustainable collaboration: Managing conflict and cooperation in interorganizational systems. MIS Q. 1996, 20, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuroni, A.C.; Haller, S.; van Winden, W.; Carabias-Hütter, V.; Yildirim, O. Public value creation in a smart city context: An analysis framework. In Setting Foundations for the Creation of Public Value in Smart Cities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sancino, A.; Hudson, L. Leadership in, of, and for smart cities–case studies from Europe, America, and Australia. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 701–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).