The Crossfire Rhetoric. Success in Danger vs. Unsustainable Growth. Analysis of Tourism Stakeholders’ Narratives in the Spanish Press (2008–2019)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Characters: These may be individuals or groups who appear as heroes, culprits, victims, allies, or beneficiaries. The villain is the individual or group that is asserted to be the cause of a policy problem and the victim is the person or group harmed either directly or indirectly by the villain and/or the policy that allows the villain to exist. [37] (p. 145). The hero of a policy narrative is the supposed fixer of a problem [37] (p. 145), often the one telling the story or closely allied to the individual or group telling the story.

- Plot: understood as elements of the story that connect the characters to each other, or organising devices that link characters to each other via motive and relationships and situate the story and its occupants in time and space [36].

- Causal mechanism: understood as the identification of the factors responsible for the problem or that contribute to producing it, and these can be intentional, inadvertent, mechanical, or accidental [37].

- Solutions: possible responses to the problems presented by the actors.

- Distribution of the costs and benefits: both of doing something about the problem and of not doing something and which social actors benefit in each case.

3. Results: Controversies between “Success in Danger” and “Unsustainable Saturation”

3.1. The Narrative of Success in Danger

3.1.1. The Characters

“Tourismphobia has become a form of protest used by radical groups to discredit and stain a sector that moves billions of euros in Spain. It has its structural defects, but in no way can the large numbers of jobs it generates be endangered, because of the large number of jobs it generates (...)”Diario de León, 17 August 2017.

“The truth is that the phenomenon of tourism, which has been the goose that lays the golden egg for many Spanish regions, has recently become the object and target of certain campaigns by the radical left.”La Razón, 12 July 2018.

“The delayed condemnation by the City Hall also unleashed a political storm. The opposition sees an intention to hide the attack and blames Colau for what they do not hesitate to label “tourismphobia.” “When you hide acts of vandalism you are basically justifying them.”El País, 31 July 2017.

“Although the driving forces behind this unique movement have different and multiform nuances, they are all united by a common denominator: their anti-capitalist mentality applied in their analysis to the tourist industry (...) the tourismphobes are hostile, both to the free movement of people and to that of services if we include tourism in this sector (...) they seem ready to finish one of the greatest sources of wealth creation in Spain (...) the tourist sector accounts for around 11% of GDP (...) the tourist industry accounts for around 13% of total employment, the equivalent of some 2.5 million jobs (...) a substantial reduction in tourist flows received from abroad or from Spanish citizens would have a very negative economic and social effect.”El Mundo, 3 September 2017.

“... more and more venture capital investment companies are buying up entire buildings to obtain very high returns, generating social tension and “tourismphobia”. This is the great fallacy of holiday rentals and the collaborative economy (...) The increase in tourists has not meant that hotel occupancy has increased proportionally, a large part of this increase has been absorbed by holiday home vacancies (...) What this simple image does reflect is the lack of control that exists.”ABC, 6 November 2017.

3.1.2. The Plot

“Tourism is a powerful socio-economic engine. It drives employment, construction, agriculture and telecommunications. Its turnover equals or exceeds that of oil exports, the food industry or the automobile industry. Spain is clinging to tourism like a lifebelt in the midst of a shipwreck.”El País, 24 January 2019.

“Complaints about too many visitors, in part fuelled by Ada Colau government’s view of tourism as an uncomfortable reality, may once again put Barcelona’s main industry in trouble.”ABC, 14 August 2018.

“It is tourismphobia pure and simple; an attitude based on a poorly concealed aversion to entrepreneurship and economic growth, the result of the utopian approaches (...) of a determined extreme left halfway between post- and pre-Marxism (...). Colau comes to curtail the entrepreneurial spirit and business creativity that have made this city an urban, economic and social benchmark at the European and world level. For the good of the people of Barcelona, this situation must be urgently rectified.”OK Diario, 19 March 2019.

3.1.3. Causal Mechanism

“In reality, the so-called tourismphobia is simply an alibi (...). Because for these radical parties that are on the extreme left and behave like fascists, Spain is the enemy to beat.”Lavozdeasturias.es, 13 August 2017.

“They are neither childish activities nor a mistake, but rather xenophobic attitudes, and a desperate attempt to regain and achieve a visibility that, it seems, political action does not grant them on other issues,”Ecodiario.es, 17 August 2017.

“It is entirely reasonable that some people are protesting against the tourist rental of flats, which is currently illegal and causes so much inconvenience to residents. But this is a long way from making derogatory comments against tourists and it would be a good idea for everyone to behave with restraint and to try to limit the motives for their protests. Tourist rentals are one thing, tourists are quite another.”Diario de Mallorca, 26 May 2017.

3.1.4. Solutions

“The Ministry of the Interior must act firmly to stop this phenomenon, which has been exported from Barcelona to the Balearic Islands and to some cities in the Valencian Community (...). It is necessary to act now at the police and judicial level.”Huelvainformacion.es, 4 August 2017.

“We have to demand that the rules are complied with (...) but we cannot encourage the idea that tourism is an enemy because, on the contrary, it is a source of wealth.”Ecodiario.es, 10 August 2017.

“Institutional declarations must be approved to serve as an antidote to the latent intimidation that can be seen in the demonstrations (...) This is not the time to attack tourists.”DiariosigloXXI.com, 8 August 2017.

“The great paradox of all this is that, if you are not legalised, you do not count for the State, you do not appear on the inspection lists, you do not exist fiscally, you can carry out the activity without paying taxes, without registering your staff or complying with the innumerable tourism regulations.”ABC, 6 November 2017.

“What is clear is that we are not playing by the same rules. I am not in favour of banning, but of regulating.”ABC, 6 November 2017.

“Sensible regulation of the tourist sector is not a desecration of the legal use of private property to make it profitable, but a way of defending it and promoting it (...)”.El Mundo, 8 August 2017.

3.2. Unsustainable Saturation Narrative

3.2.1. The Characters

What is happening is not phobia of tourism; it is not hatred or fear: it is the consequence of mismanagement of the tourism model (...) What the media, politicians and members of the tourism sector are now calling a phobia is an epidemic that has already spread elsewhere: the so-called Venice syndrome. It is the reaction of residents of tourist destinations to socially and urbanistically unsustainable models, a reaction against the transformation of space into a stage, a theme park where the inhabitants of tourist destinations are no longer able to inhabit their spaces.”Huffington Post, 21 August 2017.

“Although sun and beach tourism also brings with it problems related to overcrowding—at least in a specific and localised way—with the unprecedented number of tourists landing in the main cities since 2015, new phenomena have appeared. And tourismphobia has become the word to bring them all together (...) Effectively combating the collateral effects of an activity that is beneficial to the economy in itself is a priority for the sector.”El Mundo, 25 November 2017.

“There is a criticism of the tourist industry, which we understand to be anti-social”, states the activist, who considers that the negative impact of the 28 million visitors in the city is reflected in the poor working conditions and the cost in the price of renting flats.”El País, 11 February 2018.

“The crossover of interests between holiday homeowners, tour operators and digital platforms has given rise to words such as turistification or gentrification.”ABC, 15 October 2018.

“What do we want to do with our cities? (...) the current model is “bread for today and hunger for tomorrow” and, moreover, is “incompatible” with that of a “liveable city.””El diario.es, 10 August 2017.

3.2.2. The Plot

“Today, the guardians of the macro-economy and the entrepreneurs of the sector still regard tourists as manna from heaven. But for the residents of the most visited neighbourhoods, the spell has been broken.”El Mundo, 11 July 2016.

“... the level of spending by visitors is low and barely leaves profit margins. As if that were not enough, the employment generated by this activity is increasingly precarious and less qualified. For all these reasons, some experts fear the bursting of a tourist bubble.”El Economista, 25 September 2017.

“The problem is not the tourists (...) Nor can tourism in itself be a problem, just as agriculture or industry cannot be; in any case, the problem will be the model of tourism, agriculture or industry. To be more precise, the problem may lie in the monoculture, whether of pine trees, screw factories or tapas bars for tourists. Even more so when this monoculture is favoured by action and/or omission on the part of those in power, who are more concerned with meeting the demands of lobbies than the needs and rights of the population.”Kaos en la Red, 8 August 2017.

“Every million tourists that Spain receives generate some 25 million kilos of carbon dioxide, 1.5 million kilos of waste, 300 million litres of wastewater and consume 11 million litres of fuel, 300 million litres of water and two million kilos of food.”El Confidencial, 20 August 2017.

“Local residents have been the protagonists of various anti-tourism campaigns. They complain about the increase in housing prices, the disappearance of traditional commerce and the increase in noise and dirt that cause problems of coexistence. They do not clearly see the advantages that tourism brings them.”El País, 11 July 2017.

“... difficulty of access to housing due to the uncontrolled rise in rents, the increase in prices and the transformation of local commerce, the saturation of the public transport network, the overcrowding of streets and squares, the excessive use of infrastructures, the precariousness of working conditions, the banalization of urban and natural environments and, once again, pollution.”Diario.es, 19 July 2018.

“So, what is called ‘Tourismphobia’ could be more like ‘Enough is enough’. Tourism tends towards saturation (...) Moreover, if you look at the classic holiday destinations, they are not rich places but places for the rich. (...) It is not about stigmatising tourism, but about diversifying and enjoying the best of tourism, but putting an end to the idea that anything goes to make money, under a law of silence. Critical awareness is now called tourismphobia.”El Mundo, 11 July 2017.

3.2.3. Causal Mechanism

“Tourism contributes around 16% of GDP and although the arrival of foreigners in Spain will set a new record this year, the level of spending by visitors is low and leaves little profit margin. As if that were not enough, the employment generated by this activity is increasingly precarious and less qualified.”El Economista, 25 September 2017.

“The problem is the “lack of policies” of the administration and the “lack of planning for mature destinations.”Diario del Siglo XXI, 10 August 2017.

3.2.4. Solutions

“... not to mix an issue such as the ‘reprehensible and inadmissible’ acts of violence against tourist infrastructures that have taken place in various Spanish cities, with the debate on issues relating to the sustained and balanced growth, ‘without oversizing’ of tourism.”20minutos.es, 9 August 2017.

“We lack a critical, structured analysis, focused on a productive proposal. We do not have an alternative discourse that considers tourism for what it is, our oil. This is leading left-wing political actors to take partial solutions, which do nothing to solve the problem as a whole.”El Salto Diario, 5 December 2017.

“No country wants to or can give up an activity that brings so many tangible and intangible benefits, but the massification of recent times has pushed many governments to set certain limits, both to preserve their jewels and to guarantee a certain peace and coexistence.”Laprovincia.es, 28 August 2019.

“Sensible regulation of the tourist sector is not a desecration of the legal use of private property to make it profitable, but a way of defending and promoting it.”El Mundo, 7 August 2017.

“... promote technologies to avoid saturation points and collapse (...) lines of public assistance for companies or municipalities that guarantee the application of sustainability indicators.”El País, 28 February 2018.

“A community-based model based on the new demand would integrate local producers, from agri-food to those based on construction or furniture (...) Tourist areas that have their own vineyards and wineries. Offering products based on endemic species. Operating with a locally based and specifically rural workforce. Respectful of the environment and culture, being at the same time highly productive and industrially profitable.”El Salto Diario, 5 December 2017.

“To believe that the municipality, as a level of public administration, is capable of curbing an industry that is globally articulated and facilitated by a multitude of regulators from the European Union downwards is science fiction.”El diario.es, 26 February 2019.

“In the first place, it would be necessary to dismantle institutional logics that support and grant privileges to the tourist industry, privileges that are based on the supposed social benefit of the industry (...) Second, it would be interesting to reinforce spaces for the generation of knowledge derived from activist or militant research, which are responsible for bringing science down to earth, to analyse and make visible the real impacts of the tourist and real estate industry on the daily lives of the city’s inhabitants. Thirdly, it would be transformative to facilitate the construction of alternative and cooperative economy projects in all the sectors that are considered most strategic for the reproduction of life ...”El diario.es, 26 February 2019.

3.2.5. Distribution of Costs and Benefits

“... the investigative journalism platform Investico and the magazine De Groene Amsterdammer, published a study in which they show that the economic benefits of tourism are overestimated and the costs underestimated. The profits end up, according to the study, with a small group of large companies, some of which are members of multinational chains.”El diario.es, 2 August 2018.

“The cost is borne by some (residents), and the benefits go to others (tourism entrepreneurs) (...) Let’s be honest. Tourism is a real nuisance. We don’t even notice what good it does for the majority of mortals (except for the usual lobby).”Diariodecadiz.es, 11 September 17.

“The challenge of matching quantity and sustainability has become a priority for a successful sector that has become the oil of the Spanish economy (…)The paradox is that this strength of the tourism sector, if not achieved in a sustainable way, may have its years numbered, as nobody wants to visit a city where you cannot take a step without literally bumping into herds of tourists wandering from one place to another in search of the emblematic places.”ABC 22 January 2018.

4. Discussion

4.1. Tourism Saturation as a Wicked Problem

4.2. The Media Facilitate the Setting of the Scene

4.3. Two Conflicting Narratives

“... I was delighted to see the debate on tourist overcrowding in the media this summer; obviously, I do not agree with the way in which some people have raised it in the street, but neither do I agree with those who justify any outrage on the grounds of the economic importance of the sector. Denying that there is a problem does not contribute to its solution and, what is worse, will aggravate it year by year (...). The misnamed tourismphobia is nothing more than a growing concern, which I share, about a process of seasonal overcrowding that is not unrelated to the previous deterioration of the coasts and property speculation in towns and cities. Faced with this, faced with the simplistic view that measures success by the number of visitors, we can only address the issue and consider challenges such as deseasonalisation, differentiation of supply and destinations and, why not, some limitations. In short, common sense.”La Voz de Galicia, 6 September 2017.

“There is no denial that tourism is one of the most important industries in the world and one of the fundamental motors of the Andalusian economic sector (...) Despite its advantages, tourism is one of the activities with the most negative consequences for the environment. To begin with, it contributes to climate change, which is mainly due to the environmental impact of travel, but it also leaves a significant—and damaging—impact on the environment, both for natural spaces and for the inhabitants of nearby areas.”El Correo de Andalucía, 27 August 2017.

4.4. The Pressure on Decision-Makers

“… we are witnessing a battle between traditional hotel and apartment accommodation and the rise of holiday rentals, which are more economical and attractive for those who are fleeing mass tourism and want to get to know the city they are visiting in depth.”ABC, 9 May 2018.

4.5. Why the Use of the Term “Tourismphobia” Is in Decline

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Velasco González, M. La política turística. Una arena de acción autónoma. Cuad. Tur. 2011, 27, 953–969. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe, J. Tribes, territories and networks in the tourism academy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, D.; Brown, F. Tourism and Welfare: Ethics, Responsibility and Sustainable Well-Being; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. More than an ‘‘industry’’: The forgotten power of tourism as a social force. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1192–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Justice tourism: A pathway to alternative globalisation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateljevic, I.; Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N. (Eds.) The Critical Turn in Tourism Studies: Innovative Research Methodologies; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dredge, D.; Jamal, T. Progress in tourism planning and policy: A post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simão, J.N.; Partidário, M.d.R. How does tourism planning contribute to sustainable development? Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B. Governance, the state and sustainable tourism: A political economy approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Ekström, F.; Engeset, A.B.; Aall, C. Transition management: A tool for implementing sustainable tourism scenarios? J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, B.D.; McLennan, C.L.J.; Ruhanen, L.; Weiler, B. Tracking the concept of sustainability in Australian tourism policy and planning documents. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Critical sustainability: Setting the limits to growth and responsibility in tourism. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fodness, D. The problematic nature of sustainable tourism: Some implications for planners and managers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1671–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Brown, F. Tourism and Welfare: Ethics, Responsibility and Sustainable Well-Being; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dredge, D.; Gyimóthy, S. The collaborative economy and tourism: Critical perspectives, questionable claims and silenced voices. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Travel and Tourism Council. Coping with Success: Managing Overcrowding in Tourism Destinations; World Travel and Tourism Council: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Postma, A. Research for TRAN Committee—Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses; European Parliament, Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies, Transport and Tourism: Brussels, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions, Volume 2: Case Studies; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequera, J.; Nofre, J. Debates Shaken, not stirred. New debates on touristification and the limits of gentrification. City 2018, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomb, C.; Novy, J. (Eds.) Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City; Routledge: London, UK; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J.M.; Novelli, M. Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; CABI: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic, T. Conceptualising overtourism: A sustainability approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.G. The problem of policy problems. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pr. 2005, 7, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.W. Wicked problems in public policy. Public Policy 2008, 3, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoppe, R. The Governance of Problems: Puzzling, Power, Participation; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rochefort, D.A.; Cobb, R.W. The Politics of Problem Definition; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, C. Analyzing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be? Pearson Education: Frenchs Forest, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.G. What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program. Policy Soc. 2017, 36, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fischer, F.; Forester, J. (Eds.) The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schattschneider, E.E. The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America; Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.D.; Radaelli, C.M. The narrative policy framework: Child or monster? Crit. Policy Stud. 2015, 9, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D.; Shanahan, E.A.; McBeth, M.K. (Eds.) The Science of Stories: Applications of Narrative Policy Framework; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, E.A.; Jones, M.D.; McBeth, M.K.; Radaelli, C.M. The narrative policy framework. In The Theories of the Policy Process, 4th ed.; Weible, C.M., Sabatier, P.A., Eds.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2017; pp. 173–213. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, D.A. Policy, Paradox and Political Reason; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Knoepfel, P.; Larrue, C.; Varone, F. Analyse et Pilotage des Politiques Publiques; Helbing and Lichtenhahn: Basel, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kettell, D.; Cairney, P. Taking the power of ideas seriously—The case of the United Kingdom’s 2008 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill. Policy Stud. 2010, 31, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.; Jobert, B. L’Etat en Action. Politiques Publiques et Corporatismes; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Knill, C.; Tosun, J. Public Policy. A New Introduction; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dery, D. Problem Definition in Policy Analysis; University of Kansas Press: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A.; Rein, M. Frame Reflection: Toward the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, E.A.; Jones, M.D.; McBeth, M.K. Policy narratives and policy processes. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 535–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majone, G. Evidence, Argument and Persuasion in the Policy Process; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, E.A.; McBeth, M.K.; Hathaway, P.L.; Arnell, R.J. Conduit or contributor? The role of media in policy change theory. Policy Sci. 2008, 41, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, E.A.; McBeth, M.K.; Hathaway, P.L. Narrative policy framework: The influence of media policy narratives on public opinion. Policy Politics 2011, 39, 373–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F.; Katz, E. Personal Influence. The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Communication; Transaction Publishers: London, UK, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M.; Dearing, J.W.; Bregman, D. The anatomy of agenda-setting research. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. Up and down with ecology-the issue-attention cycle. Public Interest 1972, 28, 38. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, M.E.; Shaw, D.L. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 1972, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M.W.; De Rosa, C.; Howze, E.; Baldwin, G. Understanding wicked problems: A key to advancing environmental health promotion. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.J. Super wicked problems and climate change: Restraining the present to liberate the future. Cornell Law Rev. 2009, 94, 1153–1234. Available online: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol94/iss5/8 (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Turnpenny, J.; Lorenzoni, I.; Jones, M. Noisy and definitely not normal: Responding to wicked issues in the environment, energy and health. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, C. Problematizations in health policy: Questioning how “Problems” are constituted in policies. SAGE Open 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirschke, S.; Franke, C.; Newig, J.; Borchardt, D. Clusters of water governance problems and their effects on policy delivery. Policy Soc. 2018, 38, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fazito, M.; Scott, M.; Russell, P. The dynamics of tourism discourses and policy in Brazil. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco González, M.; Carrillo Barroso, E. The short life of a concept: Tourismphobia in the Spanish media. Narratives, actors and agendas. Investig. Tur. 2021, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; McBeth, M.K. A narrative policy framework: Clear enough to be wrong? Policy Stud. J. 2010, 38, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, E.A.; Jones, M.D.; McBeth, M.K.; Lane, R.R. Narrative policy framework. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 453–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, E.A.; Jones, M.D.; McBeth, M.K. How to conduct a narrative policy framework study. Soc. Sci. J. 2018, 55, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weible, C.M.; Olofsson, K.L.; Costie, D.P.; Katz, J.; Heikkila, T. Enhancing precision and clarity in the study of policy narratives: An analysis of climate and air issues in Delhi, India. Rev. Policy Res. 2016, 33, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBeth, M.K.; Clemons, R.S.; Husmann, M.A.; Kusko, E.; Gaarden, A. The social construction of a crisis: Policy narratives and contemporary U.S. obesity policy. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2013, 4, 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, G.; Jones, M.D. A qualitative narrative policy framework? Examining the policy narratives of US campaign finance regulatory reform. Public Policy Adm. 2016, 31, 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D. Cultural characters and climate change: How heroes shape our perception of climate science. Soc. Sci. Q. 2013, 95, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, J. Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barcelona City Council. Citizens surveys URL. 2021. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/es/informacion-administrativa/registro-de-encuestas-y-estudios-de-opinion (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Crow, D.; Jones, M. Narratives as tools for influencing policy change. Policy Polit. 2018, 46, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, R.; Mantecón, A. El auge de la turismofobia ¿hipótesis de investigación o ruido ideológico? Pasos. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2018, 16, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Romero, A.; Blàzquez-Salom, M.; Morell, M.; Fletcher, R. Not tourism-phobia but urban-philia: Understanding stakeholders’ perceptions of urban touristification. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liotta, P.H. Boomerang effect: The convergence of national and human security. Secur. Dialog. 2002, 33, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Jenkins-Smith, H. Anthony Downs’ ‘Up and Down with Ecology: The Issue-Attention Cycle. In The Oxford Handbook of Classics in Public Policy and Administration; Balla, S.J., Lodge, M., Page, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 316–325. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco González, M. La Política Turística. Gobierno y Administración Turística en España (1952–2003); Tirant Lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

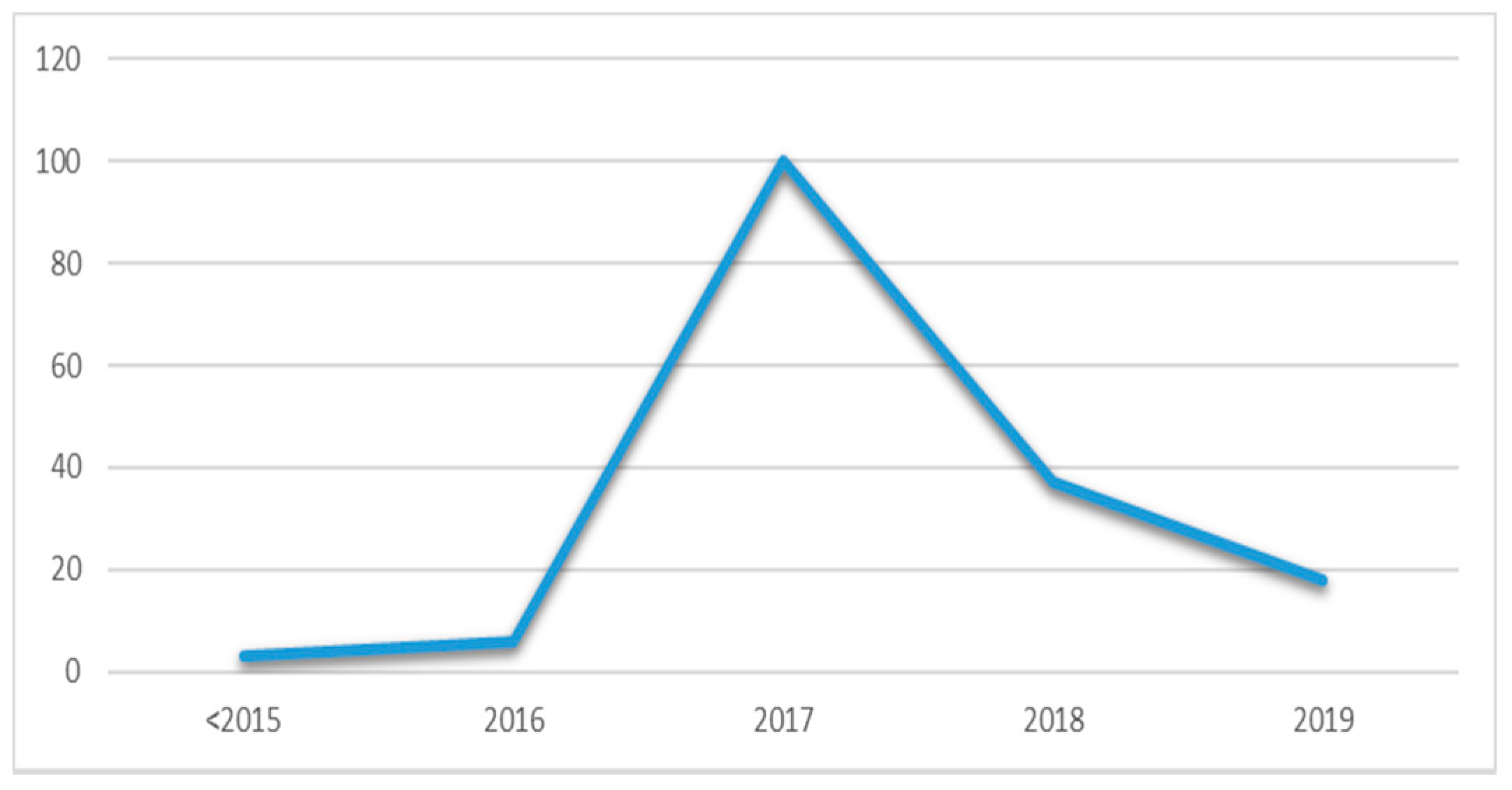

| Year | Headlines Referring to Tourismphobia | Number of News Stories Analysed That Year |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 3 | 1 |

| 2009 | 6 | 1 |

| 2010 | 1 | |

| 2011 | 2 | |

| 2012 | 11 | |

| 2013 | 15 | |

| 2014 | 36 | 1 |

| 2015 | 91 | 2 |

| 2016 | 246 | 7 |

| 2017 | 11,831 | 100 |

| 2018 | 4476 | 47 |

| 2019 | 2223 | 18 |

| Total | 18,941 | 174 |

| Characters | Hero: Those who take action with the purpose of achieving or opposing a policy solution. | Labelled with the character to be coded |

| Villain: Those who create harm or inflict damage or pain upon a victim. | ||

| Victim: Those who are harmed by a particular action or inaction. | ||

| Plot | “Story of Decline”: if the plot describes how in the beginning things were good, but got worse, and are now so bad that something must be done. | 1 |

| “Stymied Progress”: if the plot describes how things were terrible, got better due to a hero, but are getting worse because someone/thing is interfering with the hero’s work. | 2 | |

| “Change Is Only an Illusion”: if the plot describes how everyone always thought things were getting worse (or better) but they were wrong the whole time. | 3 | |

| “Story of Helplessness and Control”: if the plot describes a situation as bad, and it must be acceptable because it was unchangeable, but describes how change can occur. | 4 | |

| “Conspiracy”: if the plot describes a story moving from fate to control, but also having a twist in the tail ending that a certain small group knew how to control it all along and has been keeping control for its own benefit | 5 | |

| “Blame the Victim”: if the plot describes a story moving from fate to control but locates the control in the hands of those suffering from the problem. | 6 | |

| Causal mechanism | “Causal Mechanism: Mechanical Cause”: Does the excerpt associate intended consequences of unguided actions with a policy problem? | 1 |

| “Causal Mechanism: Intentional Cause”: Does the excerpt associate intended consequences of purposeful actions with a policy problem? | 2 | |

| Causal Mechanism: Accidental Cause”: Does the excerpt associate unintended consequences of unguided actions with a policy problem? | 3 | |

| “Causal Mechanism: Inadvertent Cause”: Does the excerpt associate unintended consequences with purposeful action with a policy solution? | 4 | |

| Solutions | The range of policy solutions | Solution X, Solution Y… |

| Cost–benefit distribution | Who benefits from the proposed policy solution? | Labelled with the character to be coded |

| Who benefits from the opposed policy solution? | ||

| Who bears the cost of the proposed policy solution? | ||

| Who bears the cost of the opposed policy solution? |

| Success in Danger | Unsustainable Saturation | |

|---|---|---|

| Characters | Hero: the tourism sector (joint effort, contribution to GDP and employment) | Hero 1: citizens themselves |

| Villain 1: young left-wing radicals | Hero 2: actors and social movements | |

| Villain 2 (accomplices): mayor and government of Barcelona for inaction against activist groups, mismanagement, and excessive interventionism in the market. | ||

| Villain 3: digital tourist accommodation platforms (mainly, Airbnb) and illegal apartment owners | ||

| Victim: employment, wealth, Spain’s image as a tourist destination | Victim: residents in saturated areas | |

| Plot | Development is being hampered and something needs to be done to avoid jeopardising such an important activity for the country. | This is a story of decline. Tourism is good, but its development has gotten out of control, leading to a situation of saturation in some places that is unsustainable. |

| Causal mechanism | Overtourism is an alibi to destabilise the main Spanish industry. If there is dysfunction, it is due to the lack of regulation of digital platforms and tourist apartments, which threaten the industry that contributes so much to the country. | Overtourism is caused by tourism development that has exceeded the limits of social sustainability. |

| Solutions | 1. Repressive: political and judicial2. Regulatory: aimed at the information sector3. Declaratory: through the active involvement of public administrations | Introducing a more sustainable model |

| Cost–benefit distribution if nothing is done | The costs of this situation are being borne by traditional tourism entrepreneurs and society as a whole, while the benefits accrue to the new digital enterprises/collaborative economy. | The cost is borne by some citizens (the affected residents) and the benefits accrue to tourism entrepreneurs (traditional and new). |

| Cost–benefit scenario if the proposed solution is implemented | The costs will be borne by new, non-traditional tourism entrepreneurs, and the gains by society as a whole. | The cost will be borne by tourism entrepreneurs and the benefits will accrue to society as a whole. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velasco González, M.; Ruano, J.M. The Crossfire Rhetoric. Success in Danger vs. Unsustainable Growth. Analysis of Tourism Stakeholders’ Narratives in the Spanish Press (2008–2019). Sustainability 2021, 13, 9127. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169127

Velasco González M, Ruano JM. The Crossfire Rhetoric. Success in Danger vs. Unsustainable Growth. Analysis of Tourism Stakeholders’ Narratives in the Spanish Press (2008–2019). Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):9127. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169127

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelasco González, María, and José M. Ruano. 2021. "The Crossfire Rhetoric. Success in Danger vs. Unsustainable Growth. Analysis of Tourism Stakeholders’ Narratives in the Spanish Press (2008–2019)" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 9127. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169127

APA StyleVelasco González, M., & Ruano, J. M. (2021). The Crossfire Rhetoric. Success in Danger vs. Unsustainable Growth. Analysis of Tourism Stakeholders’ Narratives in the Spanish Press (2008–2019). Sustainability, 13(16), 9127. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169127