Tourism Impacts, Tourism-Phobia and Gentrification in Historic Centers: The Cases of Málaga (Spain) and Gdansk (Poland)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Context

3. Methodology

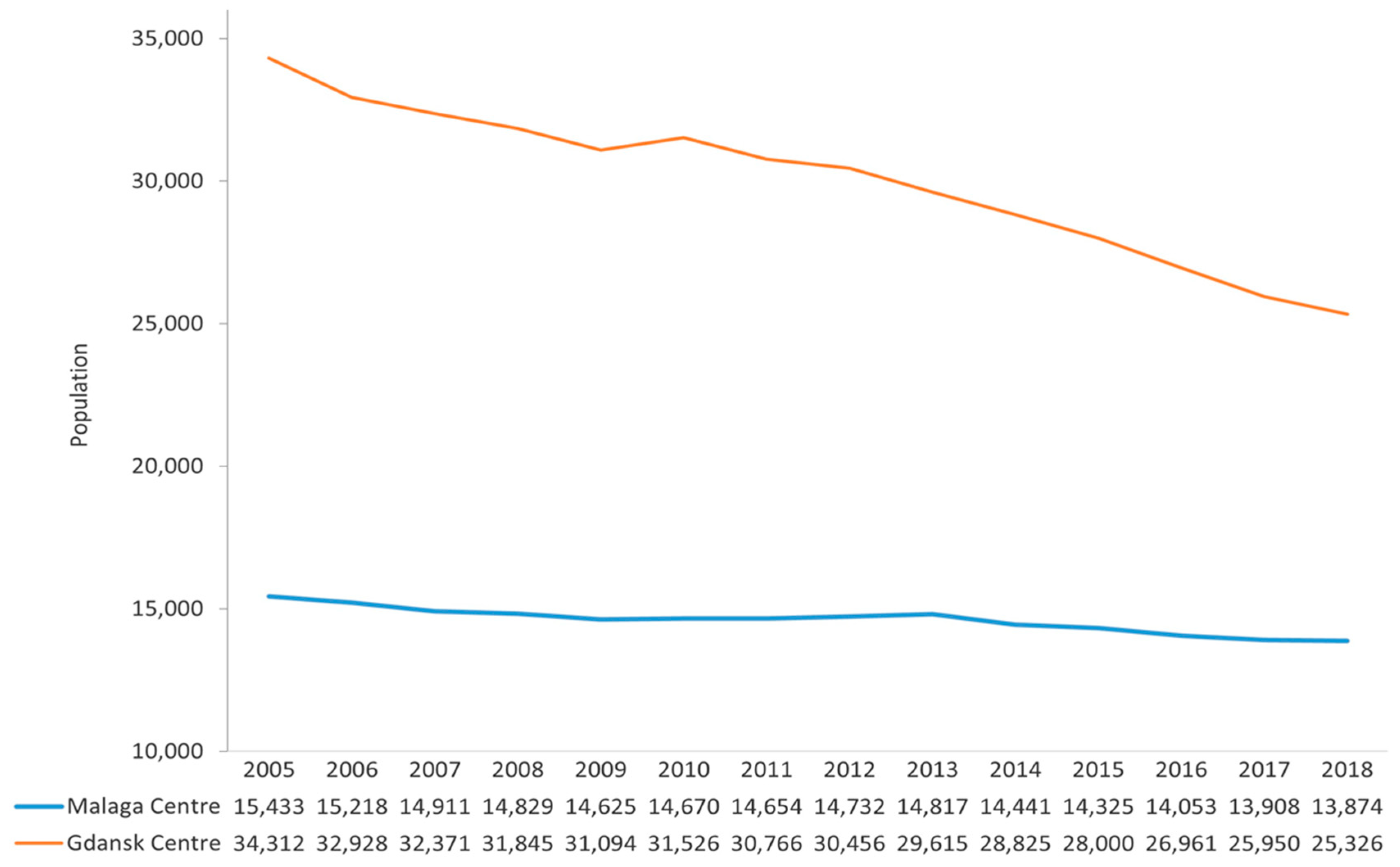

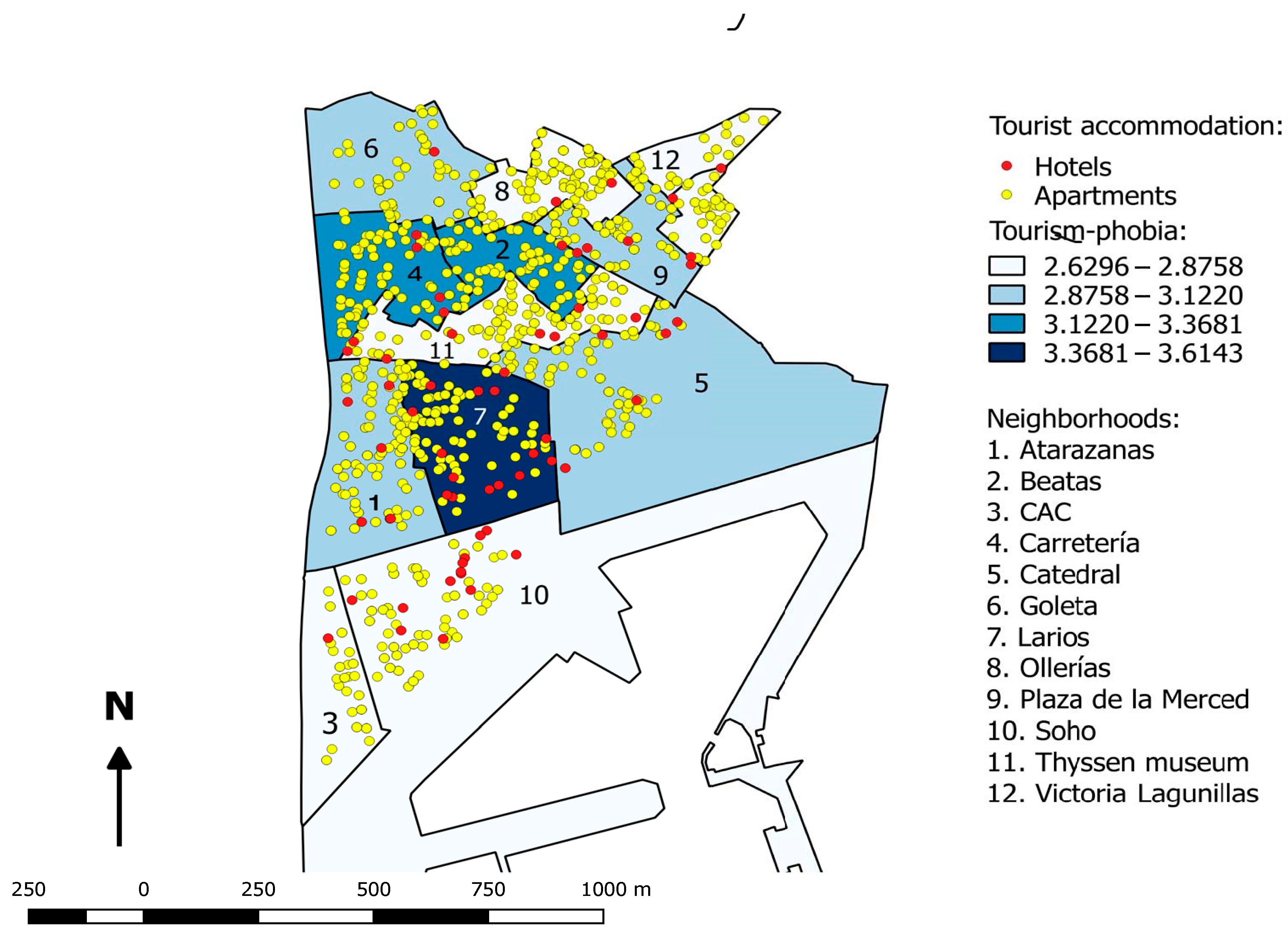

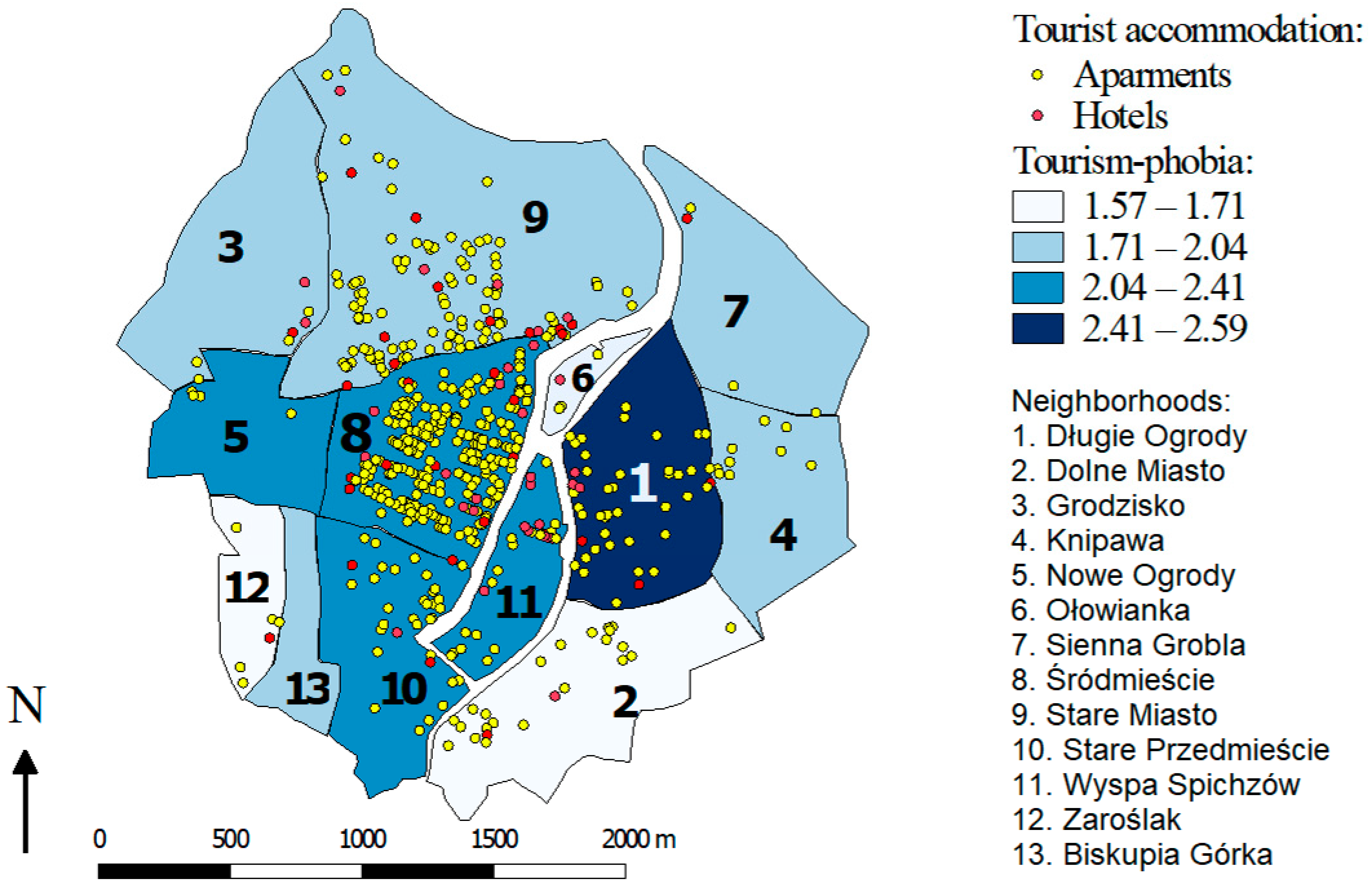

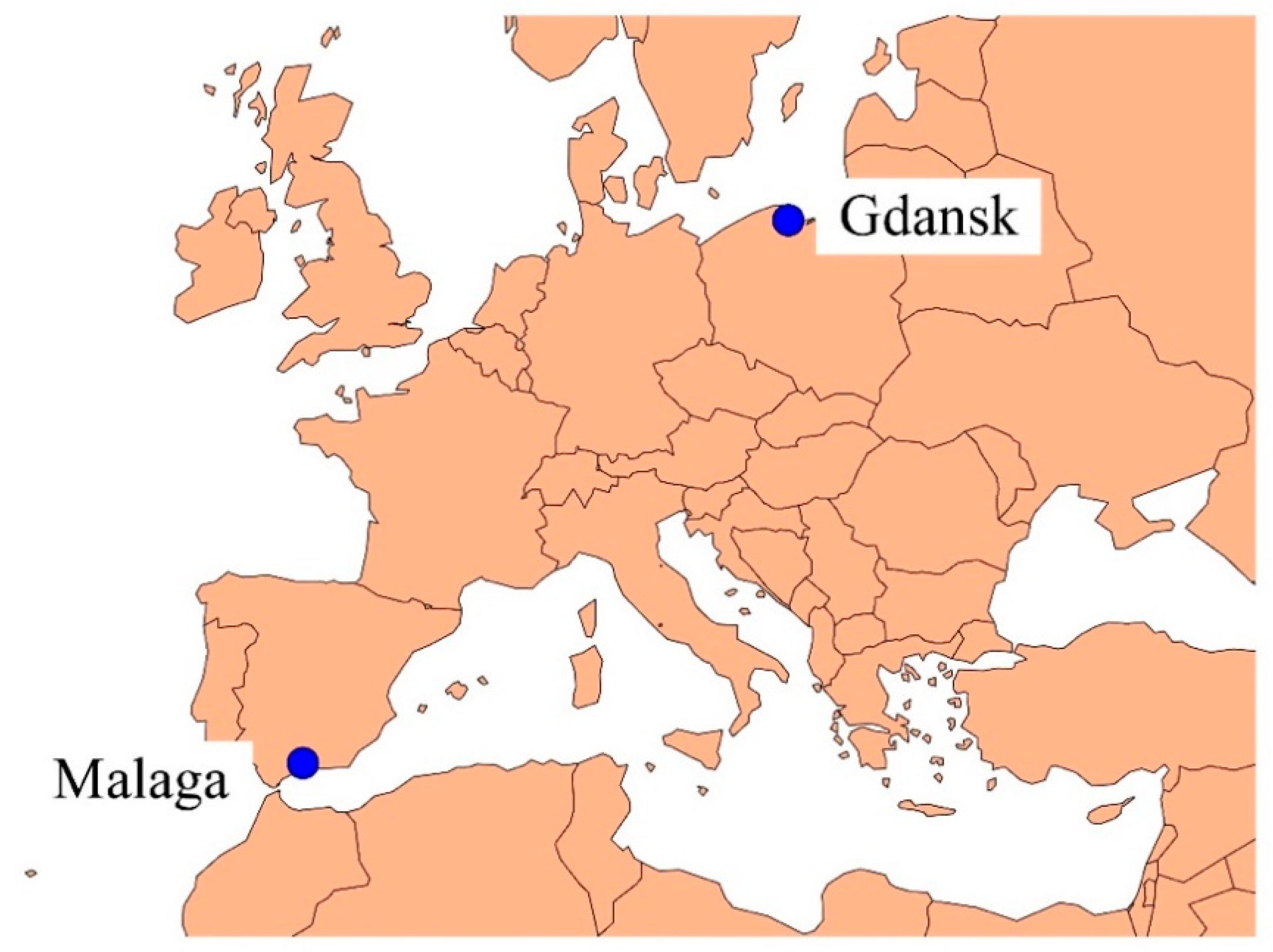

3.1. Study Areas

| Gdansk | Málaga | |

|---|---|---|

| City inhabitants | 466,631 (2018) | 574,654 (2019) |

| Study area inhabitants | 23,326 (2018) | 13,874 (2018) |

| Study area (Km2) | 5.65 | 1.1 |

| Visitors | 3,110,755 (2018) | 44,429,170 (2018) |

| Hotels | 36 (2020) | 46 (2020) |

| Apartments | 664 (2019) | 1085 (2019) |

| Average stay (nights) | 4.0 (2018) | 1.9 (2018) |

3.2. Analysis Tools

- (i)

- Sociodemographic aspects: gender, age, marital status, place of birth, level of education and job relating to tourism or not (Table 2).

- (ii)

- Tourism gentrification and tourism impacts scale. The proposed items are intended to measure the discomfort perceived by residents in the study area, in relation to aspects or processes connected with gentrification. The tourism gentrification scale is composed of items 7–12, and we use twelve items for the analysis, numbers 1–12 (Table 3) [87].

- (iii)

- (iv)

- Assessment by residents of aspects of local tourism management. The scale comprises three items (numbers 22–24) (Table 3).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Resident Profiles in the Study Areas

| Málaga | Gdansk | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women (57.7%) | Women (63.2%) |

| Age | 46–65 years old (43.7%) | >66 years old (41.6%) |

| Marital status | Married or with a partner (49.7%) | Married (49.5%) |

| Place of birth | City of Málaga (57.9%) | City of Gdansk (54.5%) |

| Length of residence | More than 11 years (61.1%) | More than 11 years (76.1%) |

| Level of education | University-educated (52.6%) | Secondary (50.1%) |

| Work related to tourism | No (70.9%) | No (86.3%) |

- Factor 1 for tourism gentrification and impacts that affect the quality of life of the resident (items: 1, 4, 7–12).

- Factor 2 for tourism-phobia related to the presence of tourists and the loss of identity of the resident’s location (items: 15, 18–21).

- Factor 3 for impacts related to the hotel business (items 3–6)

- Factor 4 for tourism-phobia related to the behavior of tourists and their consequences (items: 13, 14, 16 and 17).

- Factor 5 for local management (items 22–24).

| Components | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. It bothers me to see dirty streets | 0.684 | ||||

| 2. It bothers me that there is noise at night caused by pubs, bars and restaurants | 0.698 | ||||

| 3. It bothers me that some people from the city come to the center of town to make it dirty, make noise or get drunk | 0.515 | ||||

| 4. It bothers me that there are few parks and gardens in the center | 0.567 | ||||

| 5. It bothers me that there are so many bars, cafes, restaurants, pubs, etc. | 0.809 | ||||

| 6. It bothers me that the terraces of bars and cafes take up so much public space | 0.765 | ||||

| 7. It bothers me that prices have risen in stores and supermarkets | 0.615 | ||||

| 8. It bothers me that there are so many tourist apartments | 0.438 | ||||

| 9. It bothers me that the housing rental prices have risen | 0.726 | ||||

| 10. It bothers me that the neighbors had to move | 0.650 | ||||

| 11. It bothers me that traditional shops are disappearing in the center | 0.761 | ||||

| 12. I am bothered by the lack of public facilities in the center: senior centers, health centers, libraries, etc. | 0.641 | ||||

| 13. I am annoyed by the dirt and bad smell in some streets due to tourism | 0.648 | ||||

| 14. I am annoyed by the noise caused by tourism | 0.630 | ||||

| 15. I am annoyed seeing tourists everywhere in the center | 0.540 | ||||

| 16. I am annoyed by the bad behavior of some tourists | 0.734 | ||||

| 17. I am annoyed by tourists’ binge drinking | 0.597 | ||||

| 18. I am annoyed by so many cruise ships coming | 0.702 | ||||

| 19. I am annoyed by tourists in general | 0.785 | ||||

| 20. I am annoyed that the city center is a place for tourists | 0.731 | ||||

| 21. I am annoyed that investments in the historic center have been allocated to urban restoration related to tourism | 0.769 | ||||

| 22. I am annoyed by the lack of Council regulation in the center | 0.735 | ||||

| 23. I am annoyed that the center is becoming a place for tourists, not for residents | 0.614 | ||||

| 24. I am annoyed the Council does not listen to the opinion of residents | 0.715 | ||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin | 0.949 | ||||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Chi-squared (12,502.875) gl (300) Sig. (0.000) | ||||

| Extraction method: principal component analysis. Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization. (a) The rotation converged in 6 iterations. | |||||

| No/A Little | Somewhat | Yes, a Lot and an Awful Lot | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4–5 (%) | Item Average | |||||

| Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | |

| 1. It bothers me to see dirty streets | 3.7 | 48.4 | 5.8 | 32.4 | 90.5 | 19.2 | 4.42 | 2.53 |

| 4. It bothers me that there are few parks and gardens in the center | 10.8 | 36.6 | 9.8 | 33.2 | 79.4 | 30.3 | 4.05 | 2.77 |

| 7. It bothers me that prices have risen in stores and supermarkets | 15.4 | 37.1 | 14.3 | 33.2 | 70.3 | 29.7 | 3.87 | 2.81 |

| 8. It bothers me that there are so many tourist apartments | 24.8 | 61.6 | 11.4 | 16.1 | 63.8 | 22.3 | 3.62 | 2.26 |

| 9. It bothers me that the housing rental prices have risen | 13.5 | 50.5 | 11.1 | 26.3 | 75.4 | 23.2 | 4.08 | 2.43 |

| 10. It bothers me that the neighbors had to move | 16.9 | 45.8 | 8.7 | 28.9 | 74.4 | 25.3 | 3.98 | 2.52 |

| 11. It bothers me that traditional shops are disappearing in the center | 5.3 | 35.8 | 7.6 | 36.1 | 87.1 | 28.1 | 4.40 | 2.80 |

| 12. I am bothered by the lack of public facilities in the center: senior centers, health centers, libraries, etc. | 18.0 | 52.1 | 12.1 | 28.2 | 69.9 | 19.7 | 3.84 | 2.33 |

| Tourism gentrification (Items 7–12) | 15.7 | 47.2 | 10.9 | 28.1 | 73.5 | 24.7 | 3.97 | 2.53 |

| Total Mean | 13.6 | 46.0 | 10.1 | 29.3 | 76.4 | 24.7 | 4.03 | 2.56 |

| No/A Little | Somewhat | Yes, a Lot and an Awful Lot | Item Average | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4–5 (%) | ||||||

| Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | |

| 2. It bothers me that there is noise at night caused by pubs, bars and restaurants | 25.9 | 61.3 | 14.8 | 20.3 | 59.3 | 18.4 | 3.52 | 2.19 |

| 3. It bothers me that some people from the city come to the center of town to make it dirty, make noise or get drunk | 11.4 | 49.5 | 11.1 | 28.4 | 77.5 | 22.1 | 4.10 | 2.54 |

| 5. It bothers me that there are so many bars, cafes, restaurants, pubs, etc. | 39.1 | 77.6 | 16.4 | 9.7 | 44.5 | 12.7 | 3.04 | 1.76 |

| 6. It bothers me that the terraces of bars and cafes take up so much public space | 27.7 | 71.1 | 11.9 | 13.7 | 60.4 | 15.2 | 3.51 | 1.94 |

| Total Mean | 26.0 | 64.9 | 13.6 | 18.0 | 60.4 | 17.1 | 3.54 | 2.11 |

| No/A Little | Somewhat | Yes, a Lot and an Awful Lot | Item Average | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4–5 (%) | ||||||

| Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | |

| 13. I am annoyed by the dirt and bad smell in some streets due to tourism | 19.1 | 46.1 | 8.7 | 29.2 | 72.2 | 24.7 | 3.87 | 2.58 |

| 14. I am annoyed by the noise caused by tourism | 36.0 | 58.4 | 13.5 | 23.9 | 50.5 | 17.4 | 3.15 | 2.27 |

| 16. I am annoyed by the bad behavior of some tourists | 24.1 | 45.8 | 13.2 | 31.6 | 62.7 | 22.7 | 3.62 | 2.59 |

| 17. I am annoyed by tourists’ binge drinking | 8.8 | 42.1 | 6.3 | 28.2 | 84.9 | 29.5 | 4.35 | 2.70 |

| Tourism-phobia related to tourists’ behavior (items 13, 14, 17) F.4 | 22.0 | 48.1 | 10.4 | 28.2 | 67.6 | 23.7 | 3.75 | 2.54 |

| 15. I am annoyed seeing tourists everywhere in the center | 63.0 | 55.5 | 15.6 | 22.9 | 21.4 | 21.6 | 2.16 | 2.34 |

| 18. I am annoyed by so many cruise ships coming | 72.2 | 91.3 | 12.7 | 3.4 | 15.1 | 5.3 | 1.86 | 1.30 |

| 19. I am annoyed by tourists in general | 85.5 | 88.9 | 9.0 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 1.46 | 1.39 |

| 20. I am annoyed that the city center is a place for tourists | 73.8 | 88.2 | 14.6 | 6.8 | 11.6 | 5.0 | 1.81 | 1.37 |

| 21. I am annoyed that investments in the historic center have been allocated to urban restoration | 85.4 | 92.6 | 6.9 | 4.0 | 7.7 | 3.4 | 1.44 | 1.24 |

| Tourism-phobia related to the presence of tourists (items 15, 18–21) F.2 | 76.0 | 83.3 | 11.8 | 8.6 | 12.3 | 8.1 | 1.75 | 1.53 |

| Tourism-phobia/philia mean (items 13-21) F.2 + F.4 | 52.0 | 67.7 | 11.2 | 17.3 | 36.8 | 15.0 | 2.64 | 1.98 |

| No/A Little | Somewhat | Yes, a Lot and an Awful Lot | Item Average | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4–5 (%) | ||||||

| Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | Málaga | Gdansk | |

| 22. I am annoyed by the lack of Council regulation in the center | 22.7 | 52.1 | 13.0 | 24.5 | 64.3 | 23.4 | 3.69 | 2.49 |

| 23. I am annoyed that the center is becoming a place for tourists | 25.1 | 68.9 | 13.5 | 17.6 | 61.4 | 13.4 | 3.62 | 1.96 |

| 24. I am annoyed the Council does not listen to the opinions of residents | 18.3 | 42.9 | 9.5 | 28.4 | 72.2 | 28.7 | 3.93 | 2.73 |

| Total Mean | 22.0 | 54.6 | 12.0 | 23.5 | 66.0 | 21.9 | 3.74 | 2.40 |

4.2. Analysis of Variance: Sociodemographic Variables and Tourism-Phobia

- (a)

- Age: Significant differences were found between age groups in Málaga, with the F value found to be F = 6.253, corresponding to a −p value of 0.000. The post hoc test (Scheffé) determined that all the age groups (from 18–35 years, −p = 0.011; from 36–45, −p = 0.028; and from 46–65 years, −p = 0.001) feel greater annoyance in comparison to those over the age of 66.

- (b)

- Marital status: There are significant differences between groups with regard to marital status (F = 3.908, corresponding to a −p value of 0.004). The post hoc test (Scheffé) determined that single people and those living with their partner (−p = 0.038 and −p = 0.010, respectively) feel a higher level of annoyance than widowers.

- (c)

- Level of education: A significant link was found between the level of education and tourism-phobia (F = 9.332, corresponding to a −p value of 0.000). The post hoc test (Scheffé) determined that those who have primary studies feel much less annoyed than those who are university-educated (−p = 0.000).

- (d)

- No significant differences were found with the other variables: gender, place of birth and length of residence.

| Less Annoyed (Philia) | More Annoyed (Phobia) | Less Annoyed (Philia) | More Annoyed (Phobia) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Málaga | Gdansk | ||

| People aged over 66 | Resident aged 18–35, 36–45 and 46 to 65 | People aged over 46 (46–65 years old and over 66 years old) | Resident aged 18–35 and 36–45 |

| Widowers/widows | Single people and those living with a partner | ||

| Primary studies | University studies | ||

4.3. Results of the Analysis of Gentrification and Tourism-Phobia Scale

| Málaga and Gdansk | Value | df | Asymptotic Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age * Tourism gentrification | 137,129 | 75 | 0.000 |

| Marital Status * Tourism gentrification | 170,756 | 100 | 0.000 |

| Place of Birth * Tourism gentrification | 152,315 | 100 | 0.001 |

| Level of Education * Tourism gentrification | 116,210 | 75 | 0.002 |

| Study area (Málaga/Gdansk) * Tourism gentrification | 307,216 | 25 | 0.000 |

| Tourism-phobia Factor 2 * Tourism gentrification | 783,711 | 500 | 0.000 |

| Tourism-phobia Factor 4 * Tourism gentrification | 1,061,024 | 400 | 0.000 |

| Overall Tourism-phobia * Tourism gentrification | 1,524,514 | 900 | 0.000 |

| Value | df | Asymptotic Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Málaga | |||

| Age * Dirt due to tourism | 31,711 | 12 | 0.002 |

| Marital status * Noise due to tourism | 33,852 | 16 | 0.005 |

| Level of education * Noise due to tourism | 33,570 | 12 | 0.001 |

| Level of education * Bad behavior | 38,220 | 12 | 0.000 |

| Age * Binge drinking tourism | 27,785 | 12 | 0.000 |

| Place of residence * Tourists everywhere | 729,993 | 628 | 0.003 |

| Place of residence * Cruise ships | 733,367 | 628 | 0.002 |

| Place of residence * Tourists in general | 806,717 | 628 | 0.000 |

| Gdansk | |||

| Age * Dirt due to tourism | 28,817 | 12 | 0.004 |

| Age * Noise due to tourism | 23,242 | 12 | 0.026 |

| Age * Tourists everywhere | 45,061 | 12 | 0.000 |

| Age * Binge drinking tourism | 29,167 | 12 | 0.004 |

| Age * Binge drinking tourism | 45,129 | 12 | 0.000 |

| Age * Tourists in general | 43,263 | 12 | 0.003 |

| Place of residence * Noise due to tourism | 28,680 | 16 | 0.026 |

| Place of residence * Tourists in general | 36,881 | 16 | 0.002 |

| Length of residence * Binge drinking tourism | 24,621 | 12 | 0.017 |

| Level of education * Bad behavior | 37,224 | 12 | 0.000 |

| Level of education * Binge drinking tourism | 24,253 | 12 | 0.019 |

| Work related to tourism * Noise due tourism | 27,718 | 12 | 0.006 |

| Place of residence * Dirt due to tourism | 63,579 | 44 | 0.028 |

| Value | df | Asymptotic Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Málaga | |||

| I am annoyed that the center of Málaga is becoming a space for tourists and not for residents | 308,248 | 108 | 0.000 |

| I am annoyed by the lack of Council regulation in the center | 267,328 | 108 | 0.000 |

| I am annoyed that the Council has not been listening to the resident opinion | 253,034 | 108 | 0.000 |

| Gdansk | |||

| I am annoyed that the Old Town of Gdansk is becoming a space for tourists and not for residents | 340,882 | 100 | 0.000 |

| I am annoyed by the lack of Council regulation in the Old Town | 211,718 | 100 | 0.000 |

| I am annoyed that the Council has not been listening to the resident opinion | 229,954 | 100 | 0.000 |

5. Conclusions

- (i)

- The higher concentration of Málaga’s tourist offer in a small area than in Gdansk.

- (ii)

- The larger intensity of the tourist flow in Málaga.

- (iii)

- The low tourist seasonality of Málaga is explained due to climatic characteristics and strong diversification of the tourist offer, causing an intense presence of tourists throughout the year. Gdansk has a stronger seasonality, which allows having several months of the year in which the tourist does not bother the resident. Likely, the higher seasonality of Gdansk favors a better attitude of the resident towards the tourists [90].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Postma, A.; Buda, D.; Gugerell, K. The Future of City Tourism. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.I.; López, L.; González, F. The effects of the LCC boom on the urban tourism fabric: The viewpoint of tourism managers. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Global Report on City Tourism; UNWTO: Madrid, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stors, N. Constructing new urban tourism space through Airbnb. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiernaux, D.; González, C.I. Turismo y gentrificación: Pistas teóricas sobre una articulación. Revista Geografía Norte Grande. 2014, 58, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Calle, M. La Ciudad Histórica como Destino Turístico; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kruczek, Z. Turyści vs. mieszkańcy. Wpływ nadmiernej frekwencji turystów na proces gentryfikacji miast historycznych na przykładzie Krakowa (Tourists vs. residents. Influence of excessive tourist flow in the process of historical cities gentrification: The case of Krakow). Turystyka Kulturowa 2018, 3, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tracz, M.; Semczuk, M. Wpływ turystyki na zmianę funkcji przestrzeni miejskiej na przykładzie Krakowa, (The impact of tourism in the function change of the urban space: The case of Krakow). Biuletyn Polskiej Akademii Nauk. Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju (Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Natl. Spat. Dev. Comm.) 2018, 272, 272–284. [Google Scholar]

- García, M.; De la Calle, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural heritage and urban tourism: Historic city centres under Pressure. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkster, F.M.; Boterman, W.R. When the spell is broken: Gentrification, urban tourism and privileged discontent in the Amsterdam canal district. Cult. Geogr. 2017, 24, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Cortés, R.; Balbuena, A. Tourism-phobia in historic centres: The case of Malaga. Boletín Asociación Geógrafos Españoles 2019, 83, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opillard, F. From San Francisco’s ‘Tech Boom 2.0′ to Valparaiso’s UNESCO World Heritage Site. In Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City; Colomb, C., Novy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurran, N.; Phibbs, P. When tourists move in: How should urban planners respond to Airbnb? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravari-Barbas, M.; Jacquot, S. No conflict? Discourses and management of tourism-related tensions in Paris. In Protest and Resistance in a Tourist City; Colomb, J., Novy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, C.; Palacios, A.; Barrado, D. El comportamiento del turismo internacional con motivación cultural. El caso de las ciudades medias y pequeñas española overtourism? undertourism? (The behavior of international tourism with cultural motivation. The case of the Spanish medi-um and small cities. Overtourism? Undertourism?). In Sostenibilidad Turística: Overtourism vs Undertourism; Pons, G.X., Blanco-Romero, A., Navalón-García, R., Troitiño-Torralba, L., Blázquez-Salom, M., Eds.; Societat d’Hisòria Natural de les Balears: Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, A.; Blázquez, M.; Morell, M.; Fletcher, R. Not tourism-phobia but urban-philia: Understanding stakeholders’ perceptions of urban touristification. Boletín Asociación Geógrafos Españoles 2019, 83, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxey, G. A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants, methodology and research inferences. In Proceedings of the Travel and Tourism Research Association 6th Annual Conference Proceeding, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–11 September 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geograph./Géographe Canadien 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Cortes, R.; Balbuena, A.; Hidalgo, C. New Perspectives of Residents’ Perceptions in a Mature Seaside Destination. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szromek, A.R.; Kruczek, Z.; Walas, B. The Attitude of Tourist Destination Residents towards the Effects of Overtourism—Kraków Case Study. Sustainability 2019, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Fernández, D.; Hernández-Escampa, M.; Vázquez, A.B. Tourism management in the historic city. The impact of urban planning policies. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2016, 2, 349–367. [Google Scholar]

- Jover, J.; Díaz-Parra, I. Gentrification, transnational gentrification and touristification in Seville, Spain. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3044–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola, A. Holiday rentals: The new gentrification battlefront. Sociol. Res. Online 2016, 21, 112–120. Available online: http://www.socresonline.org.uk/21/3/10.html (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Huete, R.; Mantecón, A. El auge de la turismofobia ¿hipótesis de investigación o ruido ideológico? Pasos. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2018, 16, 9–19. Available online: http://www.pasosonline.org/Publicados/16118/PS118_01.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Ye, B.H.; Zhang, H.Q.; Yuen, P.P. Cultural conflicts or cultural cushion? Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Overtourism: A literature review to assess implications and future perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexis, P. Over-tourism and anti-tourist sentiment: An exploratory analysis and discussion. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2017, 17, 288–293. [Google Scholar]

- Perkumienė, D.; Pranskūnienė, R. Overtourism: Between the right to travel and residents’ rights. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Peláez, M.A.; Balbuena, A.; Cortés, R. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrill, R. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: A literature review with implications for tourism planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2004, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L.; Ash, J. The Golden Hordes: International Tourism and the Pleasure Periphery; Constable & Ro: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Boissevain, J. Coping with Tourists: European Reactions to Mass Tourism; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, J.K.S. Anti-tourist attitudes: Mediterranean charter tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M. Turistofobia. El País. 2007. Available online: https://elpais.com/diario/2008/07/12/catalunya/1215824840_850215.html (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Donaire, J.A. La efervescencia de la “turismofobia”. Barcelona Metrópolis. Revista de Información y Pensamiento Urbanos. 2008. Available online: http://lameva.barcelona.cat/bcnmetropolis/arxiu/es/pagea6ea.html?id=23&ui=16> (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Veríssimo, M.; Moraes, M.; Breda, Z.; Guizi, A.; Costa, C. Overtourism and tourismphobia: A systematic literature review. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2020, 68, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C. Turismofobia: Cuando el turismo entra en la agenda de los movimientos sociales. Marea urbana. Available online: http://www.levante emv.com/opinion/2017/09/06/turisme i turismofobia/1611947.html (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Milano, C. Overtourism, malestar social y turismofobia. Un debate controvertido. Pasos. Revista Turismo Patrimonio Cultural 2018, 16, 551–564. Available online: http://www.pasosonline.org/Publicados/16318/PS318_01.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, A.; Frenkel, I. Counting the ‘invisible’: Second homes in Polish statistical data collections. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2015, 7, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmyślony, P.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Urban tourism hypertrophy: Who should deal with it? The case of Krakow (Poland). Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyk, W.; Sołtysik, M.; Olearnik, J.; Barwicka, K.; Mucha, A. How Overtourism Threatens Large Urban Areas: A Case Study of the City of Wrocław, Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczak, M. Branding miejsca turystycznego na przykładzie Gdańska (Branding of a tourist place on the example of Gdańsk). Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego 2011, 663, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kęprowska, U.; Łuczak, M. Produkt turystyczny i jego ocena na przykładzie Gdańska (Tourist product and its evaluation on the example of Gdańsk). Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego 2012, 86, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Radio Gdansk. The City Lives off Tourists, but the Inhabitants Cannot Live with These Drivers. They Enter as They Want and Park Where They Want. Available online: https://m.radiogdansk.pl/wiadomosci/item/113566-miasto-zyje-z-turystow-ale-z-tymi-zmotoryzowanymi-zyc-nie-moga-mieszkancy-wjezdzaja-jak-chca-i-parkuja-gdzie-chca/113566-miasto-zyje-z-turystow-ale-z-tymi-zmotoryzowanymi-zyc-nie-moga-mieszkancy-wjezdzaja-jak-chca-i-parkuja-gdzie-chca (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Krytyka. Airbnb in the Tri-City: The Curse of Eternal Holiday. Available online: https://krytykapolityczna.pl/kraj/przeklenstwo-wiecznych-wakacji-ostrowski/ (accessed on 25 December 2019).

- Żemła, M. Reasons and Consequences of Overtourism in Contemporary Cities—Knowledge Gaps and Future Research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, J. The selling (out) of Berlin and the de- and re-politicization of urban tourism in Europe’s ‘Capital of Cool’. In Protest and Resistance in a Tourist City; Colomb, J., Novy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Miró, S.; Rullan, O. ¿Desposesión de vivienda por turistización?: Revalorización y desplazamientos en el centro histórico de Palma (Mallorca). Revista Geografía Norte Grande 2017, 67, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, J.M. The dispute over tourist cities. Tourism gentrification in the historic Centre of Palma (Majorca, Spain). Tour. Geogr. 2019, 22, 171–191. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsma, R.; Vork, J. Amsterdam Residents and Their Attitude Towards Tourists and Tourism. Coactivity Philos. Commun. Santalka Filos. Komun. 2017, 25, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mermet, A.C. Airbnb and tourism gentrification: Critical insights from the exploratory analysis of the ‘Airbnb syndrome’ in Reykjavik. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises; Gravari-Barbas, M., Guinand, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Zmyślony, P. Turystyka miejska jako źródło protestów społecznych: Przykłady Wenecji i Barcelony (Urban tourism as a source of social protests: Examples of Venice and Barcelona). Tur. Kult. 2017, 2, 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zerva, K.; Palou, S.; Blasco, D.; Benito-Donaire, J.A. Tourism-philia versus tourism-phobia: Residents and destination management organization’s publicly expressed tourism perceptions in Barcelona. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 306–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.P. The “Vicious Circle” of Tourism Development in Heritage Cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianello, M. The No Grandi Navi campaign: Protests against cruise tourism in Venice. In Protest and Resistance in a Tourist City; Colomb, J., Novy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso, A. Venice: The problema of overtourism and the impact of cruises. Investig. Reg. 2018, 42, 35–51. Available online: https://investigacionesregionales.org/article/venice-the-problem-of-overtourism-and-the-impact-of-cruises/ (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Alcalde, J.; Guitart, N.; Pitarch, A.; Vallvé, O. De la turismofobia a la convivencia turística: El caso de Barcelona. Análisis comparativo con Ámsterdam y Berlín. Ara. Revista Investigación Turismo 2018, 8, 25–34. Available online: http://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/ara/article/view/21980 (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Janusz, K.; Six, S.; Vanneste, D. Building tourism-resilient communities by incorporating residents’ perceptions? A photo-elicitation study of tourism development in Bruges. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 127–143. Available online: https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/full/10.1108/JTF-04-2017-0011 (accessed on 24 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Balbuena, A.; Cortes, R. Residents’ attitudes towards the impacts of tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, R. Aspects of change. In The Gentrification Debates: A Reader; Centre for Urban Studies, Ed.; McGibbon and Kee: London, UK, 1964; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ley, D. Artists, aestheticisation and the field of gentrification. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 2527–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Khalil, R.A.; Johar, F.; Sabri, S. The impact of new-build gentrification in Iskandar Malaysia: A case study of Nusajaya. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 202, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M. Gentrification as global habitat: A process of class formation or corporate creation? Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2007, 32, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. New globalism, new urbanism: Gentrification as global urban strategy. Antipode 2002, 34, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Salinas, V. La vivienda modesta y patrimonio cultural: Los corrales y patios de vecindad en el conjunto histórico de Sevilla. Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica Geografía Ciencias Sociales 2003, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, L.; Shin, H.B.; Morales, E.L. Global Gentrifications: Uneven Development and Displacement; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Parra, I. Viaje solo de ida: Gentrificación e intervención urbanística en Sevilla. EURE 2015, 41, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Herrero Suárez, C.A. Las viviendas de uso turístico: ¿el enemigo a abatir?: Reflexiones sobre la normativa autonómica en materia de alojamientos turísticos. Revista Estudios Europeos 2017, 70, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Munsters, W.; Freund de Klumbis, D. Culture as a Component of the Hospitality Product. In International Cultural Tourism: Management, Implications and Cases; Sigala, M., Leslie, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Hidalgo, M.C.; Salazar-Laplace, M.E.; Hess, S. Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravari-Barbas, M.; Guinand, S. (Eds.) Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises: International Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gotham, K.F. Tourism gentrification: The case of New Orleans’ vieux carre (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A. Tourism Gentrification. In Handbook of Gentrification Studies; Edward Elgar Publishing: Chetenhan, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone, D.; Préau, J. Gentrification in tourist cities: Evidence from New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina. Hous. Policy Debate 2008, 19, 137–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yrigoy, I. 580. Airbnb en Menorca: ¿Una nueva forma de gentrificación turística? Localización de la vivienda turística, agentes e impactos sobre el alquiler residencial. Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica Geografía Ciencias Sociales 2017, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gdansk City Council. Gdańsk w Liczbach. 2020. (Gdansk in Numbers. 2020). Available online: https://www.gdansk.pl/gdanskwliczbach/mieszkancy,a,108046 (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). Estadísticas del Padrón continuo. (Continuous Register Statistics). 2019. Available online: http://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- RTA (Andalusian Tourism Database). Consejería de Turismo y Deportes, Junta de Andalucía. 2019. Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/turismoydeporte/opencms/areas/turismo/registro-de-turismo/ (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). Encuesta de Ocupación Hotelera 2019. (Hotel Occupancy Survey 2019). Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Tabla.htm?path=/t11/e162eoh/a2019/l0/&file=04de022.px&L=0 (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Málaga City Council (2020). Observatorio Turístico de Málaga. 2018. Available online: http://www.malagaturismo.com/es/paginas/informes/362 (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Reina Gutiérrez, E.M. Mapeado del espacio turístico de masas. Transformaciones (adaptativas-impositivas) en el escenario urbano de Málaga (Mapping of the mass tourist area. Transformations (adaptive-imposed) in the urban scene of Malaga). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Malaga, Malaga, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- García-Bujalance, S.; Barrera-Fernández, D.; Scalici, M. Touristification in historic cities. Reflections on Malaga. Rev. Tur. Contemp. 2019, 7, 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Cocola, A. Struggling with the Leisure Class: Tourism, Gentrification and Displacement. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ceny.szybko. Pomorskie-Gdańsk-Dlugie. Ogrody-ceny-mieszkan. (Pomerania-Gdansk-Dlugie. Gardens-Apartment-Prices). 2020. Available online: www.ceny.szybko.pl/pomorskie-Gdańsk-Dlugie (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Mansilla, J.A. Vecinos en peligro de extinción. Turismo urbano, movimientos sociales y exclusión socioespacial en Barcelona. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2018, 16, 279–286. Available online: http://www.pasosonline.org/Publicados/16218/PS218_01.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Vargas, A.; Porras, N.; Plaza, M. Residents’ attitude to tourism and seasonality. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, K. The changing nature of city tourism and its possible implications for the future of cities. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2015, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R.; Parzych, K. Tourism Impacts, Tourism-Phobia and Gentrification in Historic Centers: The Cases of Málaga (Spain) and Gdansk (Poland). Sustainability 2021, 13, 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010408

Almeida-García F, Cortés-Macías R, Parzych K. Tourism Impacts, Tourism-Phobia and Gentrification in Historic Centers: The Cases of Málaga (Spain) and Gdansk (Poland). Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010408

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeida-García, Fernando, Rafael Cortés-Macías, and Krzysztof Parzych. 2021. "Tourism Impacts, Tourism-Phobia and Gentrification in Historic Centers: The Cases of Málaga (Spain) and Gdansk (Poland)" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010408

APA StyleAlmeida-García, F., Cortés-Macías, R., & Parzych, K. (2021). Tourism Impacts, Tourism-Phobia and Gentrification in Historic Centers: The Cases of Málaga (Spain) and Gdansk (Poland). Sustainability, 13(1), 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010408