Why Is Collaborative Apparel Consumption Gaining Popularity? An Empirical Study of US Gen Z Consumers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Collaborative Consumption

2.2. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

2.2.1. Attitude (AT)

2.2.2. Subjective Norms (SNs)

2.2.3. Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC)

2.3. Advancement of the TPB

2.3.1. Perceived Consumer Effectiveness (PCE)

2.3.2. Environmental Knowledge (EK)

2.3.3. Past Environmental Behavior (PEB)

2.3.4. Fashion Leadership (FL)

2.3.5. Need for Uniqueness (NFU)

2.3.6. Materialism (M)

3. Methodology

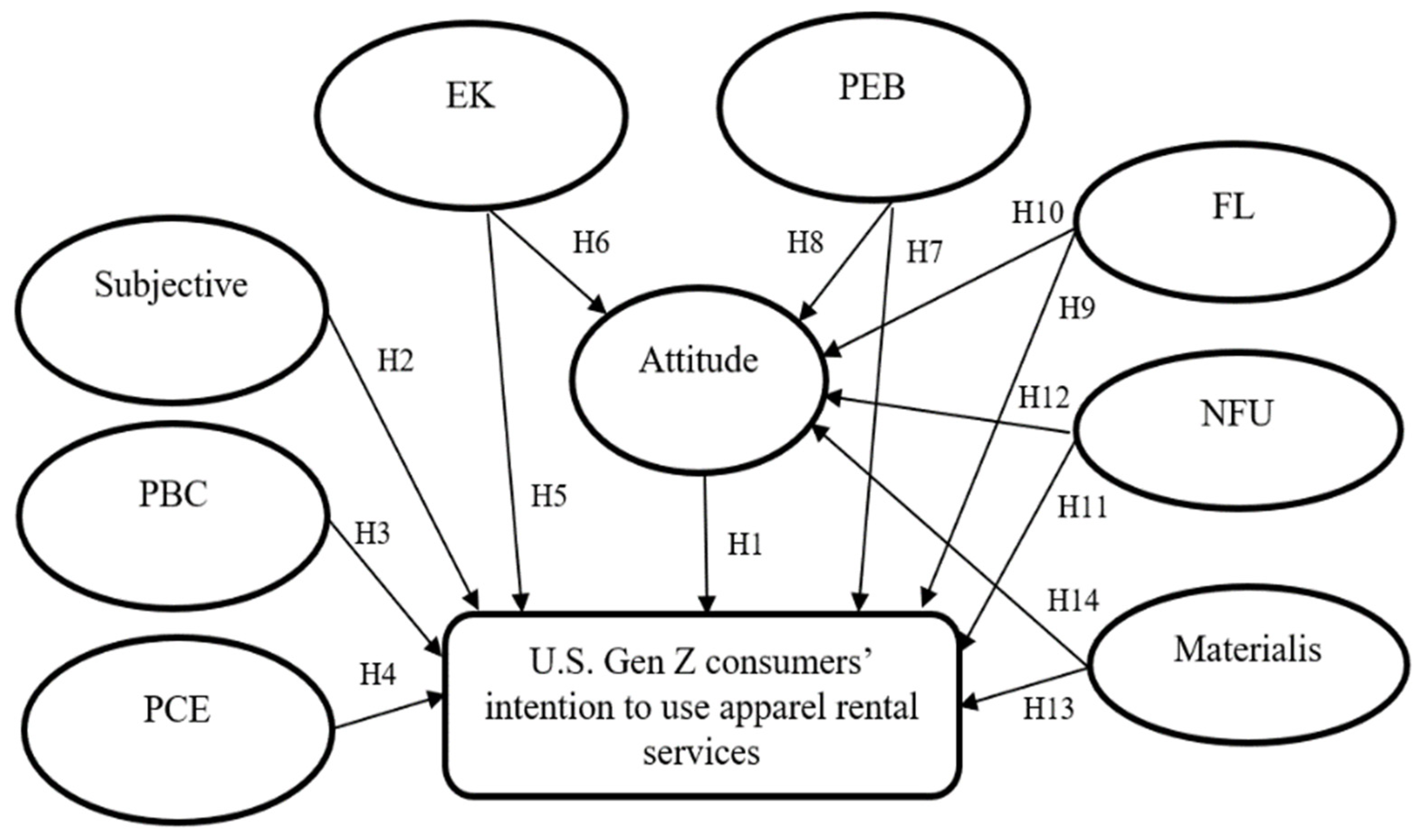

3.1. Proposed Research Model

3.2. Developed Survey Instrument

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Statistical Analysis

3.5. Psychometric Properties of Investigated Constructs

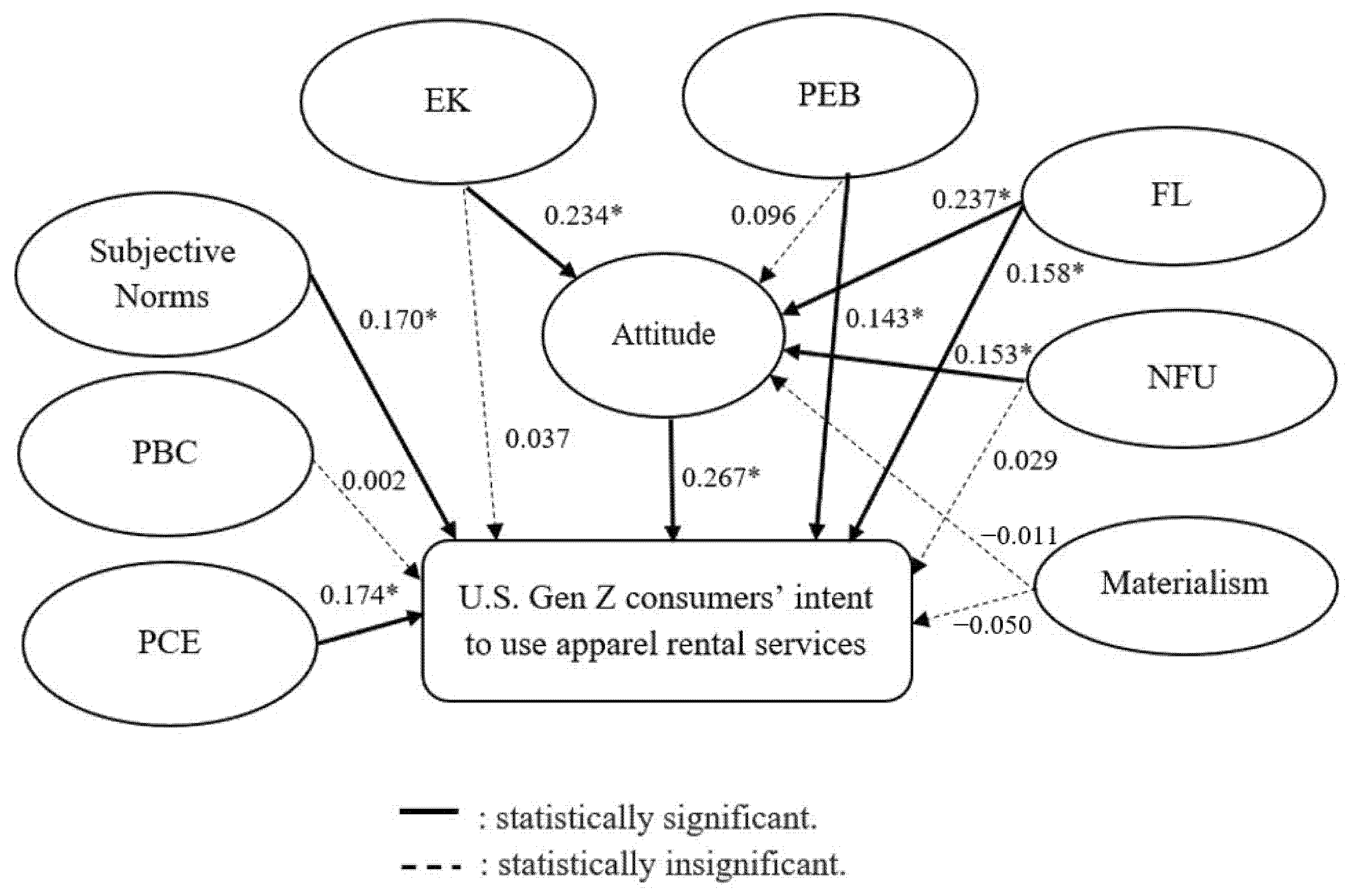

3.6. Hypothesis Testing Results and Discussions

3.7. Identified Relationships

4. Conclusions

5. Implications

6. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Measurement Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude (AT) | AT1: I like the idea of renting apparel. (0.873) AT2: Renting apparel is a good idea. (0.857) AT3: I have a favorable attitude towards apparel rental services. (0.872) | Zheng and Chi [29] |

| Subjective Norms (SN) | SN1: Close friends and family think it is a good idea for me to use apparel rental services. (0.847) SN2: The people who I listen to could influence me to use apparel rental services. (0.837) SN3: Important people in my life want me to use apparel rental services. (0.857) | Zheng and Chi [29] |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | PBC1: Using apparel rental services is entirely within my control. (0.751) PBC2: I had the resources and ability to use apparel rental services. (0.803) PBC3: I have complete control over how often to use apparel rental services. (0.781) | Zheng and Chi [29] |

| Perceived Consumer Effectiveness (PCE) | PCE1: By renting apparel, every consumer can have a positive effect on the environment. (0.864) PCE2: Every person has the power to influence environmental problems by renting apparel. (0.872) PCE3: It does not matter for protecting environment whether I rent apparel or not since one person’s act cannot make a difference. * (Dropped due to low factor loading) | Zheng and Chi [29] |

| Environmental Knowledge (EK) | EK1: I think of myself as someone who has environmental knowledge. (0.767) EK2: I know renting apparel is good for the environment. (0.844) EK3: I have taken a class or have been informed on apparel sustainability issues. (0.749) | Barbarossa and Pelsmacker [71] |

| Past Environmental Behavior (PEB) | PEB1: I guess I’ve never actually bought a product because it had a lower polluting effect. * (Dropped due to low factor loading) PEB2: I keep track of my congressman and senator’s voting records on environment issues. (0.781) PEB3: I have contacted a community agency to find out what I can do about pollution. (0.801) PEB4: I make a special effort to buy products in recyclable containers. (Dropped due to low factor loading) PEB5: I have attended a meeting of an organization specifically concerned with bettering the environment. (0.788) PEB6: I have switched products for ecological reasons. (0.772) PEB7: I have never joined a clean-up drive. * (Dropped due to low factor loading) PEB8: I have never attended a meeting related to ecology. * (0.828) PEB9: I subscribe to ecological publications. (0.778) | Fraj and Martinez [70] |

| Fashion Leadership (FL) | FL1: I am aware of fashion trends and want to be one of the first to try them. (0.821) FL2: I am the first to try new fashion; therefore, many people regard me as being a fashion leader. (0.840) FL3: It is important for me to be a fashion leader. (0.874) FL4: I am usually the first to know the latest fashion trends. (0.855) | Lang and Armstrong [58] |

| Need for Uniqueness (NFU) | NFU1: I often look for one-of-a-kind products or brands so that I create a style that is all my own. (0.804) NFU2: Often when buying product, an important goal is to find something that communicates my uniqueness. (0.806) NFU3: I often combine possessions in such a way that I create a personal image for myself that cannot be duplicated. (0.772) NFU4: I often try to find a more interesting version of ordinary products because I enjoy being original. (0.728) NFU5: I often look for new products or brands that will add to my personal uniqueness. (0.807) | Lang and Armstrong [58] |

| Materialism (M) | M1: I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and apparel. (0.863) M2: Some of the most important achievements in life include acquiring material possession. (0.824) M3: The things I own say a lot about how well I’m doing in life. (0.907) M4: I like to own things that impress people. (0.872) M5: I like a lot of luxury in my life. (0.826) | Lang and Armstrong [58] |

| Use Intention (UI) | UI1: I intend to use apparel rental services. (0.845) UI2: I will try to rent apparel instead of buying apparel. (0.824) UI3: I will make an effort to reduce apparel consumption in the future. (Dropped due to low factor loading) | Zheng and Chi [29] |

References

- Chi, T.; Gerard, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y. A study of US consumers’ intention to purchase slow fashion apparel: Understanding the key determinants. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2021, 14, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Giglio, S.; Dennis, C. Making sense of consumers’ tweets. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2019, 47, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganak, J.; Chen, Y.; Liang, D.; Liu, H.; Chi, T. Understanding US millennials’ perceived values of denim apparel recycling: Insights for brands and retailers. Int. J. Sustain. Soc. 2020, 12, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Textiles: Material-Specific Data. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/textiles-material-specific-data (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Brown, R. The Environmental Crisis Caused by Textile Waste. Available online: https://www.roadrunnerwm.com/blog/textile-waste-environmental-crisis (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Lang, C.; Li, M.; Zhao, L. Understanding consumers’ online fashion renting experiences: A text-mining approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 21, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Shen, B. Renting fashion with strategic customers in the sharing economy. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 218, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, B.; Hofmann, E.; Kirchler, E. Do we need rules for “what’s mine is yours”? Governance in collaborative consumption communities. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zamani, B.; Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Life cycle assessment of clothing libraries: Can collaborative consumption reduce the environmental impact of fast fashion? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton Incorporated. Rent Designer Now, Perhaps Buy Later. Available online: https://lifestylemonitor.cottoninc.com/sharingeconomy/?fbclid=IwAR2FuFzonHYWn6hbKuOBpmffJTaftUBua7Swh66cp-MkFfoRJIfL5IlF3RQ (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Moeller, S.; Wittkowski, K. The burdens of ownership: Reasons for preferring renting. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2010, 20, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cline, E. How Sustainable Is Renting Your Clothes, Really? Available online: https://www.elle.com/fashion/a29536207/rental-fashion-sustainability/ (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- CGS. CGS Survey Reveals ‘Sustainability’ Is Driving Demand and Customer Loyalty. Available online: https://www.cgsinc.com/en/infographics/CGS-Survey-Reveals-Sustainability-Is-Driving-Demand-and-Customer-Loyalty (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Raynor, L. Gen Z and the Future of Spend: What We Know about This Generation, The Pandemic and How They Pay. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2021/01/21/gen-z-and-the-future-of-spend-what-we-know-about-this-generation-the-pandemic-and-how-they-pay/?sh=60a4277a21eb (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M. Sharing economy: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Liquid consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 582–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, S.J.; Gleim, M.R.; Hartline, M.D. Decisions, decisions: Variations in decision-making for access-based consumption. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2021, 29, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, A.; Suseno, Y. A state-of-the-art review of the sharing economy: Scientometric mapping of the scholarship. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. Inside the sustainable consumption theoretical toolbox: Critical concepts for sustainability, consumption, and marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 78, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Huurne, M.; Ronteltap, A.; Corten, R.; Buskens, V. Antecedents of trust in the sharing economy: A systematic review. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. The sharing economy: A marketing perspective. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C. Perceived risks and enjoyment of access-based consumption: Identifying barriers and motivations to fashion renting. Fash. Text. 2018, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.C.M.; Park, H. Sustainability and collaborative apparel consumption: Putting the digital ‘sharing’ economy under the microscope. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2017, 10, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, K.-H. Motivating collaborative consumption in fashion: Consumer benefits, perceived risks, service trust, and usage intention of online fashion rental services. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chi, T. Factors influencing purchase intention towards environmentally friendly apparel: An empirical study of US consumers. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2015, 8, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; Gerard, J.; Dephillips, A.; Liu, H.; Sun, J. Why, U.S. Consumers Buy Sustainable Cotton Made Collegiate Apparel? A Study of the Key Determinants. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D.E.; Kasprzyk, D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. Health Behav. 2015, 70, 231. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Griffiths, M.A. Share more, drive less: Millennials value perception and behavioral intent in using collaborative consumption services. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 34, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitudinal and normative variables as predictors of specific behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1973, 27, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursavaş, Ö.F.; Yalçın, Y.; Bakır, E. The effect of subjective norms on preservice and in-service teachers’ behavioural intentions to use technology: A multigroup multimodel study. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 2501–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, D.; Hahn, R. Understanding collaborative consumption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior with value-based personal norms. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.K.; Mun, J.M.; Chae, Y. Antecedents to internet use to collaboratively consume apparel. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Hu, C. A study on the factors affecting consumers’ willingness to accept clothing rentals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.H.; Chung, J.E. Consumer purchase intention for organic personal care products. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Leifhold, C.V. The role of values in collaborative fashion consumption - A critical investigation through the lenses of the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, T.C.; Taylor, J.R.; Ahmed, S.A. Ecologically concerned consumers: Who are they? Ecologically concerned consumers can be identified. J. Mark. 1974, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. Feelings that make a difference: How guilt and pride convince consumers of the effectiveness of sustainable consumption choices. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, J.G. Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 10, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderjahn, I. Personality Variables and Environmental Attitudes as Predictors of Ecologically Responsible Consumption Patterns. J. Bus. Res. 1988, 17, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.C.; Lau, T.C. Green purchase behavior: Examining the influence of green environmental attitude, perceived consumer effectiveness and specific green purchase attitude. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 559–567. [Google Scholar]

- Fryxell, G.E.; Lo, C.W. The influence of environmental knowledge and values on managerial behaviours on behalf of the environment: An empirical examination of managers in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, A.L.; Harun, A.; Hussein, Z. The influence of environmental knowledge and concern on green purchase intention the role of attitude as a mediating variable. Br. J. Art Soc. Sci. 2012, 7, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R. Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, P.N.P.D.; Handayani, R.B. The effect of environmental knowledge, green advertising and environmental attitude toward green purchase intention. Russ. J. Agric. Soc. 2018, 78, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C. Information, incentives, and pro environmental consumer behavior. J. Consum. Policy 1999, 22, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richetin, J.; Perugini, M.; Conner, M.; Adjali, I.; Hurling, R.; Sengupta, A.; Greetham, D. To reduce and not to reduce resource consumption? That is two questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T.; Zheng, Y. Understanding environmentally friendly apparel consumption: An empirical study of Chinese consumers. Int. J. Sustain. Soc. 2016, 8, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamzadehmir, M.; Sparks, P.; Farsides, T. Moral licensing, moral cleansing and pro-environmental behaviour: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Armstrong, C.M.J. Collaborative consumption: The influence of fashion leadership, need for uniqueness, and materialism on female consumers’ adoption of clothing renting and swapping. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 13, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Park-Poaps, H. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping motivations of fashion leadership. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2010, 14, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, H.; Ko, E.; Zhang, T.; Mattila, P. Brand popularity as an advertising cue affecting consumer evaluation on sustainable brands: A comparison study of Korea, China, and Russia. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 789–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Durability, fashion, sustainability: The processes and practices of use. Fash. Pract. 2012, 4, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyanegara, R.C.; Tsarenko, Y.; Anderson, A. The Big Five and brand personality: Investigating the impact of consumer personality on preferences towards particular brand personality. J. Brand Manag. 2009, 16, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Fromkin, H.L. Uniqueness: The Human Pursuit of Difference, 1st ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, K.T.; Bearden, W.O.; Hunter, G.L. Consumers’ need for uniqueness: Scale development and validation. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, J.; Kidd, L. Use of the Need for Uniqueness Scale to Characterize Fashion Consumer Groups. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2000, 18, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, Y.K. Indian consumers’ purchase intention toward a United States versus local brand. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, M.; Harris, J. Individual differences in the pursuit of self-uniqueness through consumption. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 27, 1861–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ritch, E.L.; Schröder, M.J. Accessing and affording sustainability: The experience of fashion consumption within young families. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.; Niinimäki, K.; Kujala, S.; Karell, E.; Lang, C. Sustainable fashion product service systems: An exploration in consumer acceptance of new consumption models. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Martinez, E. Environmental values and lifestyles as determining factors of ecological consumer behaviour: An empirical analysis. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P. Positive and negative antecedents of purchasing eco-friendly products: A comparison between green and non-green consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.; Barrios, F.X.; Kopper, B.A.; Hauptmann, W.; Jones, J.; O’Neill, E. Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 20, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, L.; Longnecker, M.; Ott, R.L. An Introduction to Statistical Methods and Data Analysis; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, T.; Sun, Y. Development of firm export market oriented behavior: Evidence from an emerging economy. Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.A.; Vorhies, D.W.; Mason, C.H. Market orientation, marketing capabilities, and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, R.A., Jr. A parsimonious estimating technique for interaction and quadratic latent variables. J. Mark. Res. 1995, 32, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariadoss, B.J.; Chi, T.; Tansuhaj, P.; Pomirleanu, N. Influences of firm orientations on sustainable supply chain management. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3406–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khare, A. Green apparel buying: Role of past behavior, knowledge and peer influence in the assessment of green apparel perceived benefits. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Sell, give away, or donate: An exploratory study of fashion clothing disposal behavior in two countries. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2010, 20, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parry, C. Meet the Next Consumer: How Gen Z Are Taking on a New Reality. Available online: https://www.thedrum.com/news/2020/11/03/meet-the-next-consumer-how-gen-z-are-taking-new-reality. (accessed on 1 April 2021).

| Percent | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Income | ||

| 18 | 5% | Under $5000 | 9% |

| 19 | 5% | $5000 to $9999 | 7% |

| 20 | 12% | $10,000 to $14,999 | 10% |

| 21 | 17% | $15,000 to $24,999 | 13% |

| 22 | 26% | $25,000 to $34,999 | 18% |

| 23 | 35% | $35,000 to $49,999 | 15% |

| Gender | $50,000 to $74,999 | 17% | |

| Male | 63% | $75,000 to $99,999 | 9% |

| Female | 37% | $100,000 and more | 1% |

| Ethnicity | Annual Apparel Expenditure | ||

| White/Caucasian | 66% | $0–$99 | 6% |

| Black/African American | 14% | $100–$299 | 18% |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 6% | $300–$499 | 23% |

| Latino/Hispanic | 9% | $500–$699 | 17% |

| Native American | 4% | $700–$899 | 12% |

| Others | 1% | $900–$1099 | 7% |

| Education | $1100–$1499 | 8% | |

| High school diploma | 15% | $1500–$1999 | 4% |

| Associate’s degree | 23% | $2000 and more | 6% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 46% | Rented Apparel Previously | |

| Master’s degree | 16% | Yes | 55% |

| No | 45% | ||

| AT | SN | PBC | PCE | PEB | EK | FL | NFU | M | UI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 1 | 0.695 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.448 ** | 0.503 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.459 ** | 0.388 ** | 0.643 ** |

| SN | 0.483 | 1 | 0.258 ** | 0.470 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.513 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.501 ** | 0.535 ** | 0.651 ** |

| PBC | 0.120 | 0.067 | 1 | 0.424 ** | 0.142 ** | 0.322 ** | 0.283 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.248 ** | 0.288 ** |

| PCE | 0.285 | 0.221 | 0.180 | 1 | 0.338 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.522 ** | 0.511 ** | 0.375 ** | 0.542 ** |

| PEB | 0.201 | 0.294 | 0.020 | 0.114 | 1 | 0.559 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.544 ** | 0.546 ** |

| EK | 0.253 | 0.263 | 0.104 | 0.270 | 0.312 | 1 | 0.549 ** | 0.439 ** | 0.462 ** | 0.526 ** |

| FL | 0.285 | 0.404 | 0.080 | 0.272 | 0.341 | 0.301 | 1 | 0.580 ** | 0.606 ** | 0.620 ** |

| NFU | 0.211 | 0.251 | 0.098 | 0.261 | 0.141 | 0.193 | 0.336 | 1 | 0.499 ** | 0.447 ** |

| M | 0.151 | 0.286 | 0.062 | 0.141 | 0.296 | 0.194 | 0.367 | 0.249 | 1 | 0.494 ** |

| UI | 0.413 | 0.424 | 0.083 | 0.294 | 0.298 | 0.277 | 0.384 | 0.200 | 0.244 | 1 |

| Mean | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

| S.D. | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| VIF | 2.34 | 2.71 | 1.30 | 1.89 | 2.03 | 1.93 | 2.57 | 1.81 | 1.94 | - |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.835 | 0.803 | 0.796 | 0.784 | 0.841 | 0.862 | 0.869 | 0.842 | 0.911 | 0.796 |

| Construct reliability | 0.901 | 0.884 | 0.822 | 0.859 | 0.830 | 0.867 | 0.911 | 0.868 | 0.934 | 0.821 |

| AVE | 0.752 | 0.717 | 0.606 | 0.753 | 0.621 | 0.619 | 0.719 | 0.615 | 0.738 | 0.697 |

| χ2 test p value | 0.166 | 0.105 | 0.173 | 0.144 | 0.082 | 0.158 | 0.188 | 0.085 | 0.264 | 0.103 |

| Hyp. | DV | IDV | Std. Coef. (β) | t-Value | Sig. at p < 0.05 | Control Variable | Std. Coef. (β) | t-Value | Sig. at p < 0.05 | Total R2 | Sig. at p < 0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UI | Cont. | 0.713 | 0.477 | Age | 0.012 | 0.325 | 0.745 | 0.586 | <0.000 F = 37.84 (13/348) | |||

| H1 | Y | AT | 0.267 | 5.033 | 0.000 | Gender | 0.039 | 1.078 | 0.282 | |||

| H2 | Y | SN | 0.170 | 2.995 | 0.003 | Edu. | 0.022 | 0.522 | 0.602 | |||

| H3 | N | PBC | 0.002 | 0.045 | 0.964 | Income | 0.053 | 1.369 | 0.172 | |||

| H4 | Y | PCE | 0.174 | 3.644 | 0.000 | |||||||

| H5 | N | EK | 0.037 | 0.779 | 0.437 | |||||||

| H7 | Y | PEB | 0.143 | 2.898 | 0.004 | |||||||

| H9 | Y | FL | 0.158 | 2.853 | 0.005 | |||||||

| H11 | N | NFU | 0.029 | 0.615 | 0.539 | |||||||

| H13 | N | M | −0.050 | −1.032 | 0.303 | |||||||

| AT | Cont. | 1.591 | 0.113 | Age | 0.053 | 1.186 | 0.237 | 0.402 | <0.000 F = 26.323 (9/352) | |||

| H6 | Y | EK | 0.234 | 4.364 | 0.000 | Gender | 0.111 | 2.605 | 0.010 | |||

| H8 | N | PEB | 0.096 | 1.671 | 0.096 | Edu. | 0.083 | 1.635 | 0.103 | |||

| H10 | Y | FL | 0.237 | 3.810 | 0.000 | Income | 0.090 | 1.948 | 0.052 | |||

| H12 | Y | NFU | 0.153 | 2.867 | 0.004 | |||||||

| H14 | N | M | −0.011 | −0.189 | 0.850 | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCoy, L.; Wang, Y.-T.; Chi, T. Why Is Collaborative Apparel Consumption Gaining Popularity? An Empirical Study of US Gen Z Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158360

McCoy L, Wang Y-T, Chi T. Why Is Collaborative Apparel Consumption Gaining Popularity? An Empirical Study of US Gen Z Consumers. Sustainability. 2021; 13(15):8360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158360

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCoy, Lindsay, Yuan-Ting Wang, and Ting Chi. 2021. "Why Is Collaborative Apparel Consumption Gaining Popularity? An Empirical Study of US Gen Z Consumers" Sustainability 13, no. 15: 8360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158360

APA StyleMcCoy, L., Wang, Y.-T., & Chi, T. (2021). Why Is Collaborative Apparel Consumption Gaining Popularity? An Empirical Study of US Gen Z Consumers. Sustainability, 13(15), 8360. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158360