4.1. Conservancy-Related Socioeconomic Outcomes

Socioeconomic outcomes are important in determining the success or failure of community-based conservation initiatives because local community members will likely support initiatives that improve their socioeconomic wellbeing and shun those that they deem non-beneficial to them [

28,

29,

30,

31]. In the present study, we found that a vast majority (~90%) of local community members perceived improvement in their socioeconomic status following conservancy establishment. We also found that large proportions (>65%) of community members perceived conservancy-related improvements in several other socioeconomic indicators, namely, security situation, access to grazing resources, household income, access to educational and health facilities, and livestock numbers. These findings generally suggest that the community conservancy model, as applied in our study region, can improve the socio-economic wellbeing of local pastoralists.

The observed high proportion of respondents reporting perceived improvement in security situation is consistent with a recent evaluation in northern Kenya indicating that nearly eight-tenths of conservancy members felt safer due to security enhancement and peace-building efforts undertaken by conservancies [

26]. In our study region and similar pastoralist settings across sub-Saharan Africa, local communities commonly suffer from various forms of insecurity including livestock theft (e.g., through cattle raiding), wildlife poaching, banditry, invasions and illegal grazing, and conflict over natural resources [

12,

32,

33,

34]. Persistent insecurity threatens pastoralists’ socioeconomic wellbeing by impairing their ability to participate more effectively in income generating activities [

35,

36] We attribute improved security to better coordination and enhanced peace building and conflict resolution efforts under the community conservancy framework. Community conservancies in our study region often invest in community policing to complement efforts by local and national government agencies and non-governmental organizations [

26,

27,

33]. Specifically, the conservancies work closely with the Northern Rangelands Trust (NRT), Kenya’s National Police Service (NPS), the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), and county governments to provide a community-driven approach to tackling security and reducing conflict. Our key informant interviews revealed that similar security enhancement efforts are implemented in Naibunga Conservancy.

In our study, we found that local perception of improved security was positively associated with cattle ownership and camel ownership, suggesting that enhancing security is particularly important for livestock owners. Although we noted a similar association between security perception and ownership of sheep and goats, this particular finding should be interpreted with caution because it was not statistically valid (i.e., less than 80% of cells had expected frequency values equal to or greater than 5). Livestock (especially cattle, sheep, goats, and camels) are highly valued and are a major source of livelihoods for pastoral communities in Kenya’s arid and semiarid regions [

36,

37]. Therefore, pastoralists may be particularly concerned about the security of their livestock. Our findings suggest that enhancing security benefits for local pastoralists can increase their support for community-based conservation initiatives. Therefore, community conservancies should prioritize security enhancement for local communities for better socioeconomic and wildlife conservation outcomes.

At face value, the observed perceived improvements in accessibility to grazing resources and livestock numbers may appear somewhat surprising. Under the community conservancy framework in our study region, local pastoralists typically make a trade off by setting aside portions of their communal land for wildlife conservation [

1,

6,

10], which should reduce the area available for grazing their livestock. However, local community members are usually allowed to graze their livestock in these areas during the dry season [

38], thereby partly mitigating the impact of this trade off. The fact that large proportions of respondents noted these improvements suggests that it is possible to achieve a win-win outcome for both biodiversity conservation and livestock production under the community conservancy framework.

We partly attribute improvements in accessibility to grazing resources and livestock numbers to the various conservancy-driven land and grazing management initiatives that were revealed by our key informants. As our key informants attested, these initiatives may have improved rangeland condition and forage availability for both livestock and wildlife, consistent with previous findings in our region [

12,

39,

40]. Further, we relate these improvements to improved security under the community conservancy setting. Specifically, we posit that improved security reduces livestock losses to theft, thereby contributing to overall increases in livestock numbers across the landscape. In addition, we propose that improved security minimizes incursion grazing and conflicts over resources, thereby increasing forage availability for local community members’ livestock. These arguments are supported by the views of our key informants, who pointed out the negative impacts of insecurity on livestock and grazing resources. As our key informants observed, insecurity reduces accessibility to grazing resources because pastoralists tend to avoid herding their livestock in areas they consider insecure. Consequently, their high concentrations in areas considered safer leads to overgrazing and subsequent degradation of forage resources in these areas. We recommend that in addition to allowing pastoralists’ livestock to periodically access conservation areas, community conservancies can enhance socioeconomic and conservation outcomes by increasing efforts towards implementing community-based sustainable land and grazing management practices and enhancing security for local pastoralists and their livestock.

We relate the observed perceived conservancy-driven improvement in average household income to increased profitability of livestock rearing, based on the fact that an overwhelming majority of community members in our study region are pastoralists. In addition, the observed positive association between perception of increase in household income and ownership of livestock suggests that livestock keeping is a major driver of household income improvement. Under the community conservancy framework, local pastoralists can derive enhanced benefits from livestock through multiple pathways. One such pathway is the improved profitability of livestock sales through the various conservancy-driven livestock market access enhancement initiatives that were identified by our key informants. As pointed out by the key informants, such initiatives enable local pastoralists to maximize profits by selling their livestock at more competitive prices. Consistent with our findings, it was recently reported that cattle sales by pastoralists from community conservancies in northern Kenya improved by nearly 50% over a one-year period due to such livestock market enhancement initiatives [

26]. Our findings underscore the important role that such conservancy-driven livestock market access initiatives play in improving local livelihoods.

In addition to improved livestock markets, increased pastoralists’ household income could also be related to increased livestock productivity triggered by conservancy-driven improved availability of forage resources [

12,

39]. Furthermore, we posit that the improved security situation creates an enabling environment for better livestock rearing and productivity, thereby leading to improved household income for local pastoralists. Improvement in local household income can additionally be related to employment and business opportunities created by the conservancy, based on the information obtained from key informant interviews. The creation of such opportunities appears to be vital in helping local community members diversify their income streams, leading to increased local household incomes.

Our findings on perceived changes in accessibility to schools and health facilities resonate with information obtained from our key informants and the conservancy’s current strategic plan [

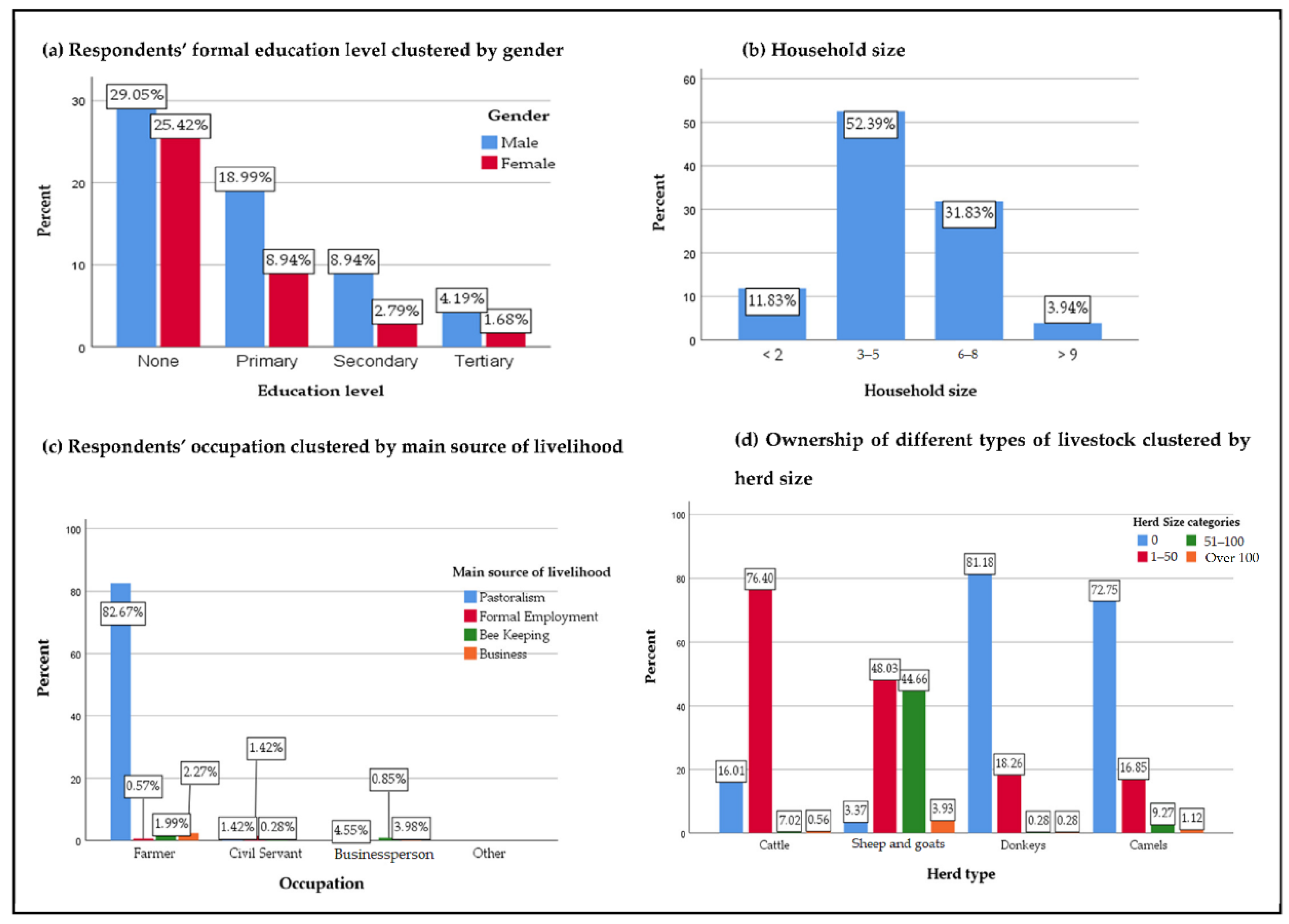

21]. Specifically, the conservancy strives to improve accessibility to schools in various ways including expanding education facilities to include adult education and boarding schools, lobbying community members to increase school enrolment, and awarding bursaries to needy students. In terms of health, the conservancy prioritizes the construction of health facilities to cover as many settlements as possible, enhancing mobile clinic and ambulance services, and the training of community health workers. The observed perceived improvements in accessibility to schools and health facilities generally suggest that the conservancy is making some progress on these fronts. However, based on our findings that the majority of local community members had no formal education, and that just one out of ten members had post-primary education, more efforts need to be directed towards enhancing accessibility to educational facilities. Notably, the observed positive association between formal education and involvement in conservancy activities suggests that expanding education opportunities for local community members will be beneficial to local community members while also contributing towards desirable outcomes for conservancy management and conservation programs.

In addition, the positive association between livestock ownership and local perception of improvement in access to both schools and health facilities suggests that livestock owners may have better access to these facilities, likely because of higher household income. This argument is consistent with the positive association between perception of improved household income and livestock ownership that was observed in this study. In addition, there is evidence that pastoralists in this region sell their livestock to pay school fees for their children [

41], further underscoring the role of livestock in enhancing accessibility to schools. Therefore, community conservancies should redouble their efforts to create a favorable environment for livestock rearing as a strategy to enhance local household incomes and accessibility to these facilities. In addition, based on the observed gender disparity in formal education (females were less educated than males), community conservancies should further direct their efforts towards enhancing girl-child education to address this disparity.

The conservancy also focuses on improving road networks and improving accessibility to water by renovating water points and constructing water pans [

21]. However, the fact that only moderate proportions (~53%) of respondents perceived improvements in these facilities indicates that much more needs to be done on these fronts. Our finding on local perceptions of change in water accessibility is consistent with information from our key informants. Whereas the key informants indicated that the conservancy attempted to increase accessibility to water, they also indicated that water scarcity remains a big challenge for local community members. As opined by our key informants, water scarcity heightens conflicts among people as well as between people and wildlife. The observed negative association between the perception of improved accessibility to water and cattle ownership suggests that available water sources are insufficient not only for people but also for livestock and wildlife. Therefore, to better enhance conservation and socioeconomic outcomes, community conservancies should focus on developing more effective strategies to improve water availability for pastoralists, their livestock, and wildlife.

The fact that an overwhelming majority (more than seven-tenths) of respondents did not note improvement in accessibility to electricity may be due to difficulties in distributing mains electricity in such vast and sparsely populated landscapes. This could be one of the reasons why improving accessibility to electricity has not been prioritized, based on the conservancy’s current strategic plan [

21]. We propose that community conservancies in such pastoral landscapes should direct more efforts towards improving local accessibility to alternative energy sources, especially solar power, if they are to better enhance the socioeconomic wellbeing of local pastoralists. Such an intervention could importantly bolster the local economy by enhancing domestic lighting, accessibility to water through solar-powered water pumps, and the use of mobile phones, which is fast expanding in these pastoral regions [

42]. In addition, improving local accessibility to solar power could contribute towards better mitigation of human–wildlife conflicts through the use of solar-powered light-emitting diode (LED) flashlights to reduce livestock depredation by lions [

43].

4.2. Local Participation in Conservancy Management and Conservation Activities

Local participation has been identified as a key determinant of socioeconomic and conservation outcomes of community-based conservation projects [

16,

17,

31,

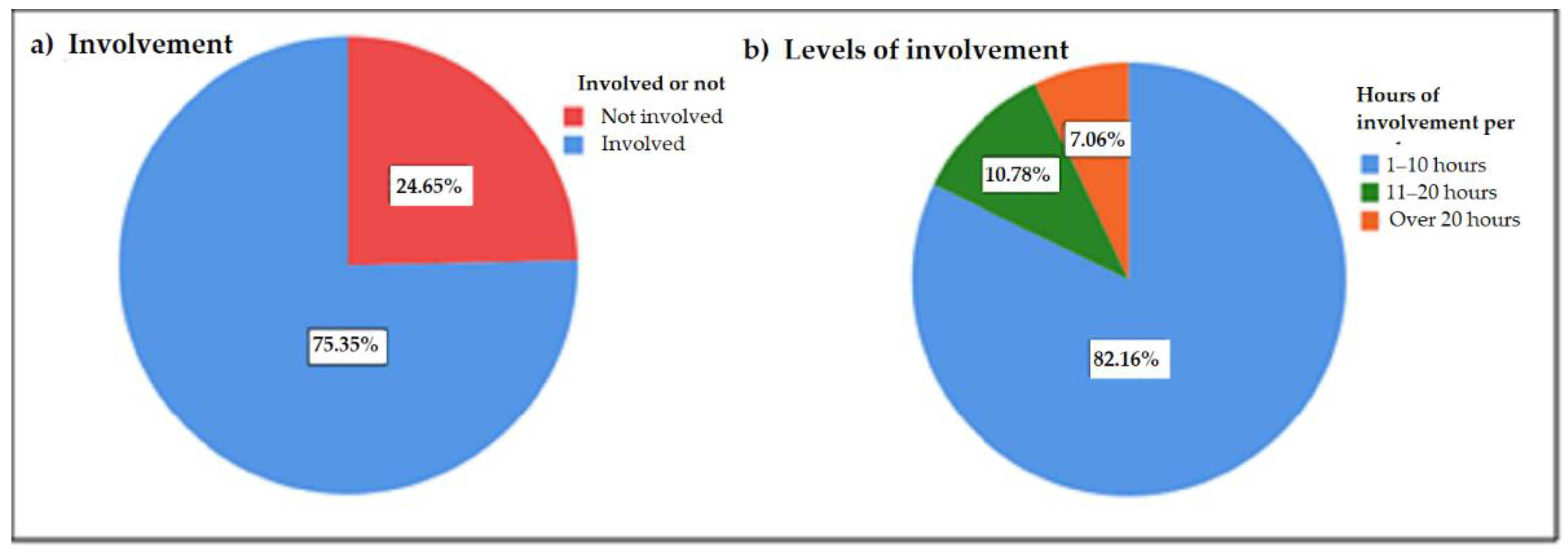

32]. In our study, key informants revealed several ways in which local community members were involved in conservancy management and conservation activities, including rangeland rehabilitation and restoration, community-based grazing management, participation in management committees, and capacity building. The observed overwhelming majority (nearly eight-tenths) of respondents reporting involvement in these activities demonstrates a considerably high level of support for the conservancy and its programs among local community members. We associate the observed high level of local community participation in conservancy activities with the observed equally high levels of local community perceptions of socioeconomic improvements. This proposition is consistent with the fact that local community members’ involvement in these activities was positively associated with their perceptions of conservancy-related socioeconomic improvements. These findings resonate with other studies showing that local perceptions of socioeconomic benefits of community-based conservation initiatives play a pivotal role in increasing local participation in such initiatives [

44,

45]. The observed overwhelming majority (approximately eight-tenths) of respondents reporting to be involved for not more than 10 h per week suggests that this is the participation level that best balances engagement in individual activities with engagement in conservancy activities.

The observed positive association between possession of formal education and respondents’ participation in conservancy management and conservation activities underscores the importance of education in enhancing local participation in conservancy programs. Education has been identified as a key factor in improving local participation in conservation [

46]. Specifically, formal education importantly prepares people to participate in activities that require the application of skills and knowledge and improves their self-confidence [

47]. The observed higher than expected proportion of females reporting involvement in conservancy management and conservation activities suggests that females can play a pivotal role in community-based initiatives, as has also been reported elsewhere [

37,

48]. It is noteworthy that this gender disparity in local participation in conservancy activities was observed despite the fact that females were generally less educated than males, yet education positively influenced local participation. While what drove gender disparity in local participation is unclear, we posit that the observed gender disparity in the perception of conservancy-related improvement in accessibility to grazing resources could be responsible. In addition, in our study region, adult males largely take care of cattle, which usually require more forage and water, and are normally herded in far-flung areas away from homesteads [

41]. Therefore, males engaged in cattle herding may have little time to participate in conservancy management and conservation activities.

The observed positive association between livestock ownership and local community members’ participation in conservancy activities can be attributed to the fact that livestock ownership was also positively associated with perception of conservancy-related socioeconomic improvements, a major determinant of local participation. Livestock owners appear to be more motivated to participate in these activities as a way of ensuring better livestock productivity and profitability. The observed negative relationship between sheep and goat herd size and involvement in conservancy activities could be due to the possibility that households with larger herd sizes have less time available to participate in conservancies as they have more animals to look after.

Based on the foregoing findings, we suggest that community conservancies should focus on addressing individual-level differences in involvement in conservancy management and conservation activities if they are to better achieve broad-based, equitable, and sustainable participation in these activities by local community members. In particular, the conservancies should prioritize identifying and addressing the disparities in local participation related to educational, gender, and livestock ownership and herd size differences among local community members.