Social Impact of Value-Based Banking: Best Practises and a Continuity Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- One approach is via principles, taxonomies and certification systems. A number of frameworks have been developed to mobilise financial resources to generate positive impact and achieve the SDGs’ goals. The principles for positive impact finance are a common framework to finance the SDGs set by the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) [28]. In June 2019, the European Union (EU) published the Sustainable Finance Taxonomy [29]. Moreover, in June 2020, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), China and the China International Center for Economic and Technical Exchanges (CICETE) think tank, published the UNDP SDG Finance Taxonomy aiming to address this missing link between SDGs and financing [30];

- A second approach is via reporting frameworks. Currently, reporting frameworks like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) are working to align with the SDGs as are newer initiatives such as the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) and the Impact Management Project (IMP). The Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) hosts IRIS+, a catalogue of generally accepted performance metrics that help investors measure and manage impact;

- A third approach is providing instruments to assess and manage impact within sustainable banks. In that sense, the Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV) has developed a Scorecard based on GABV’s Principles of Values-Based Banking [31]. It allows a bank to self-assess, monitor and communicate its progress on delivering value to society.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Practises of Value-Based Banking

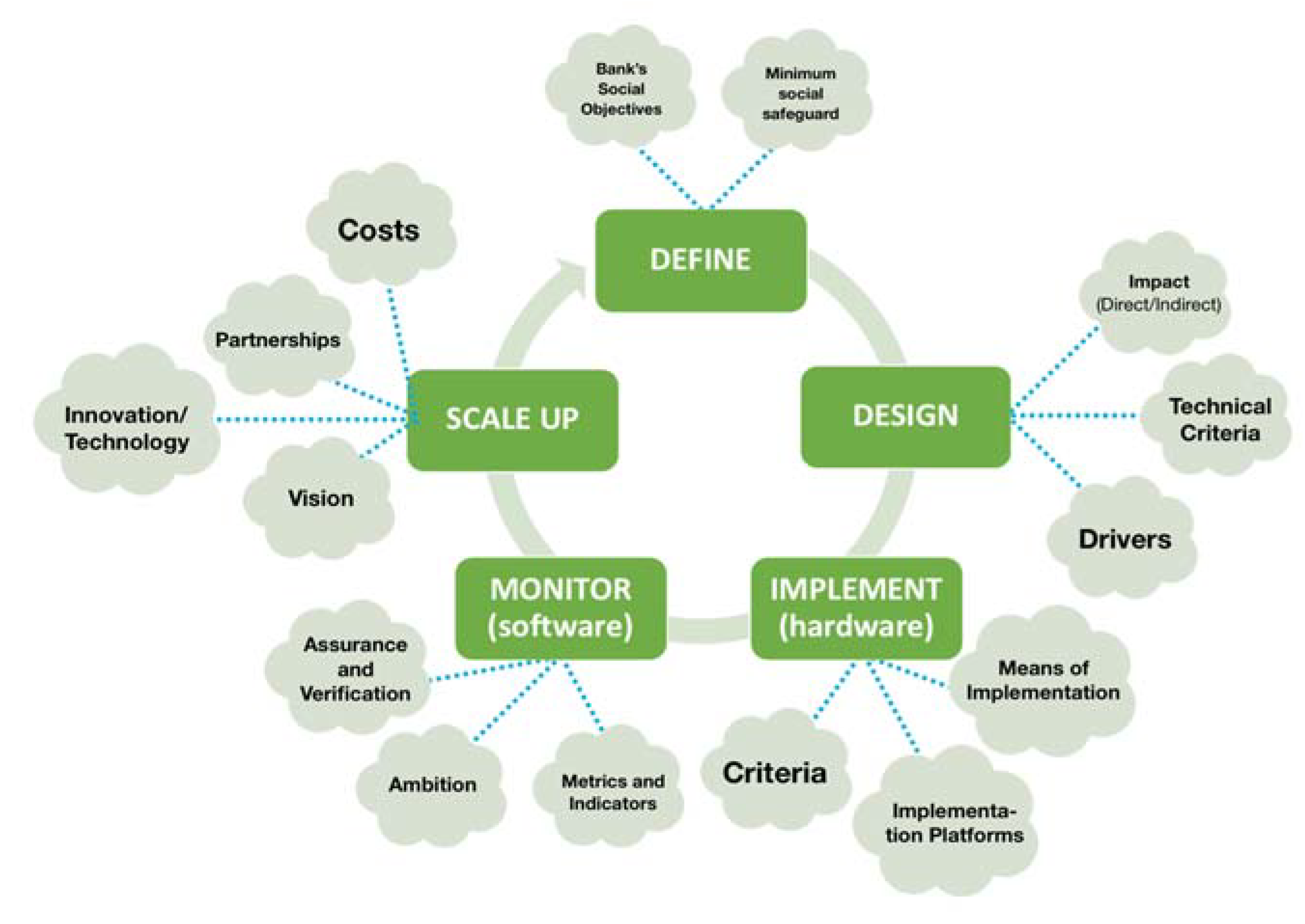

2.1.1. Practises Related to the Understanding and Definition of Social Impact

- To finance positive impact businesses;

- To deliver a positive contribution to one or more of the three pillars of sustainable development (i.e., economic, environmental and social), once any potential negative impacts to any of the pillars have been duly identified and mitigated;

- To respond to the challenge of financing the SDGs.

“We will continuously increase our positive impacts while reducing the negative impacts on, and managing the risks to, people and environment resulting from our activities, products and services. To this end, we will set and publish targets where we can have the most significant impacts.”

- Social and environmental impact and sustainability are at the heart of the business model.

- Grounded in communities, serving the real economy, and enabling new business models to meet the needs of people.

- Long-term relationships with clients and a direct understanding of their economic activities and the risks involved.

- Long-term, self-sustaining, and resilient to outside disruptions.

- Transparent and inclusive governance.

2.1.2. Practises Related to the Design Stage of Social Impact

- Scope: the bank’s core business areas and products/services across the main geographies that the bank operates in;

- The scale of exposure: where the bank’s core business/major activities lie in terms of industries, technologies and geographies;

- Context and relevance: the most relevant challenges and priorities related to sustainable development in the countries/regions in which it operates;

- The scale and salience of impact: social, economic and environmental impact resulting from the bank’s activities and provision of products and services.

2.1.3. Practises Related to the Implementation Stage of Social Impact

- Corporate governance: Co-op Bank implemented several measures to ensure that the ethical policy was embedded throughout the organisation. The bank established a “Corporate Ethical Policy” that covers five key areas: human rights; international development; ecological impact; animal welfare; social enterprise. The Co-op Bank also implemented several changes at the Board level to strengthen its monetary and credit policies and ensure its alignment with its ethical standards [51];

- Internal operations for green business transformation: Currently, banks are developing financial operations around the globe, and their impacts on society and the environment are increasingly important. Value-based banks are conscious about the energy used in its buildings. As a result, optimal management of energy efficiency is the top priority for reducing the carbon footprint. Banks conduct energy audits in all their offices for effective energy management. They also utilise renewable energy (i.e., solar, wind) to power their offices [51,52];

- Green services and products offered to the customers: Bank’s commitment to offer greener products and services to their customers is reflected in their daily practises. To reduce the consumption of paper, banks rely on electronic transactions and mobile banking. They also prioritize the use of bio-sourced and recycled materials to produce credit cards, leaflets, brochures, etc., and enlarge the useful life of credit cards to reduce the use of materials [43,50];

- Human Resource Management: Triodos Bank pays special attention to the social and ethical motivation of co-workers throughout recruitment, evaluation procedures, internal training programmes and debate and exchange sessions [50];

- Advocacy: Meanwhile at the national level, the provision of sustainable finance is capable of influencing public policy to certain extent. Value-based banks have campaigned for the introduction of such regulation and will continue to lobby for such a mandate to be applied to all large businesses [51].

2.1.4. Practises Related to the Monitoring Stage

- The activities, projects, programmes and/or entities financed;

- The processes they have in place to determine eligibility and to monitor and verify impacts;

- The impacts achieved by the activities, projects, programmes and/or entities financed.

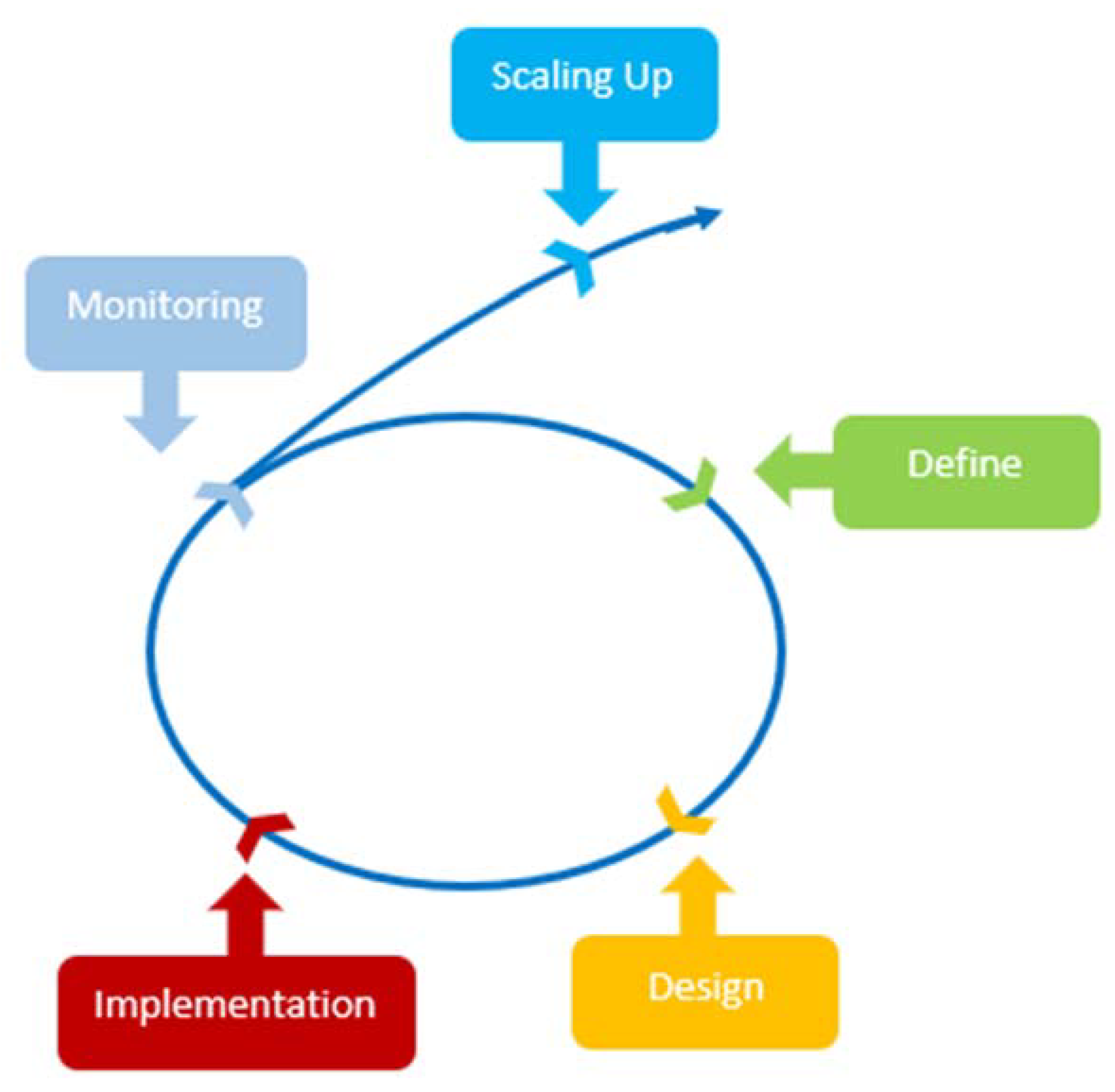

2.2. Theoretical Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

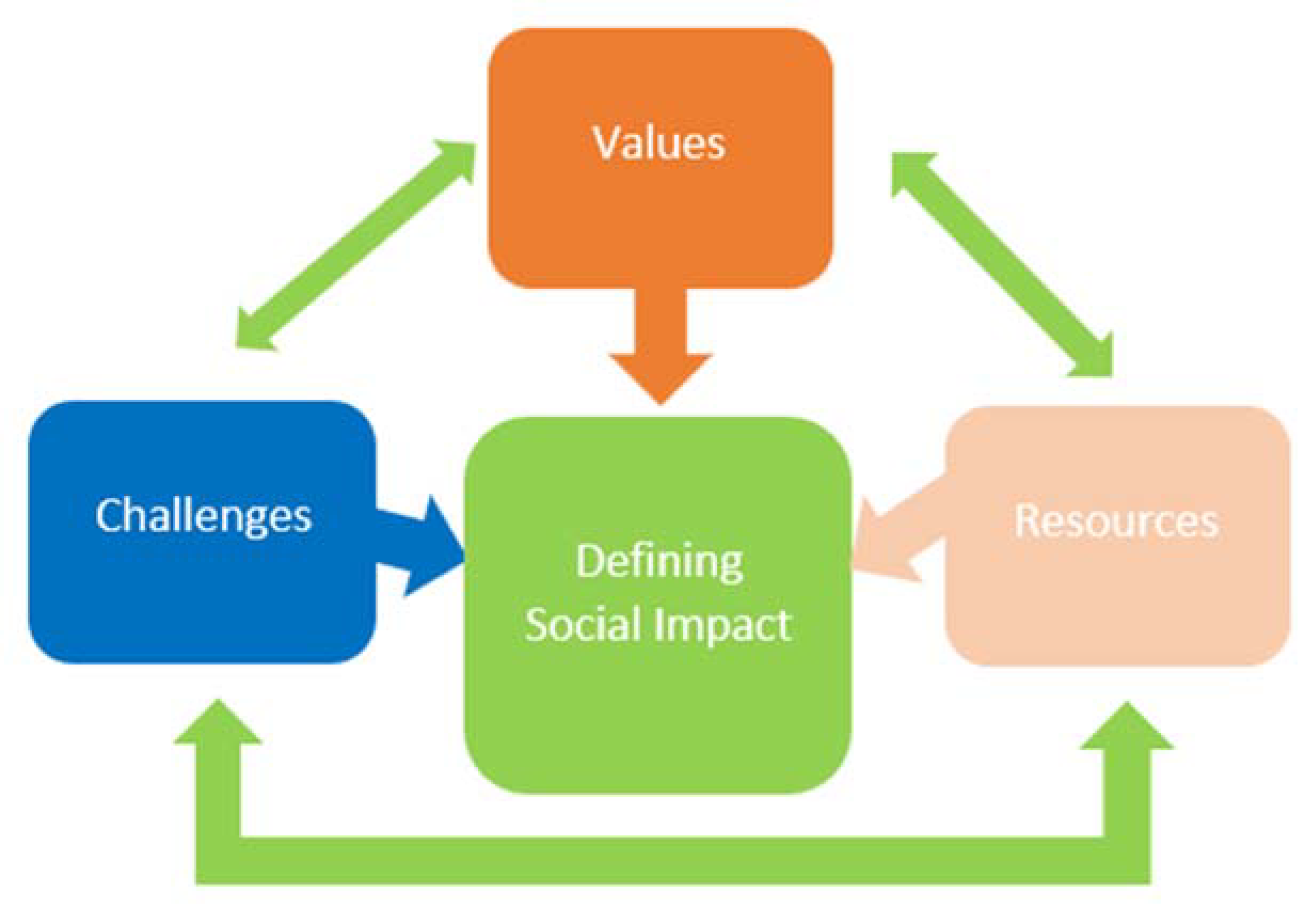

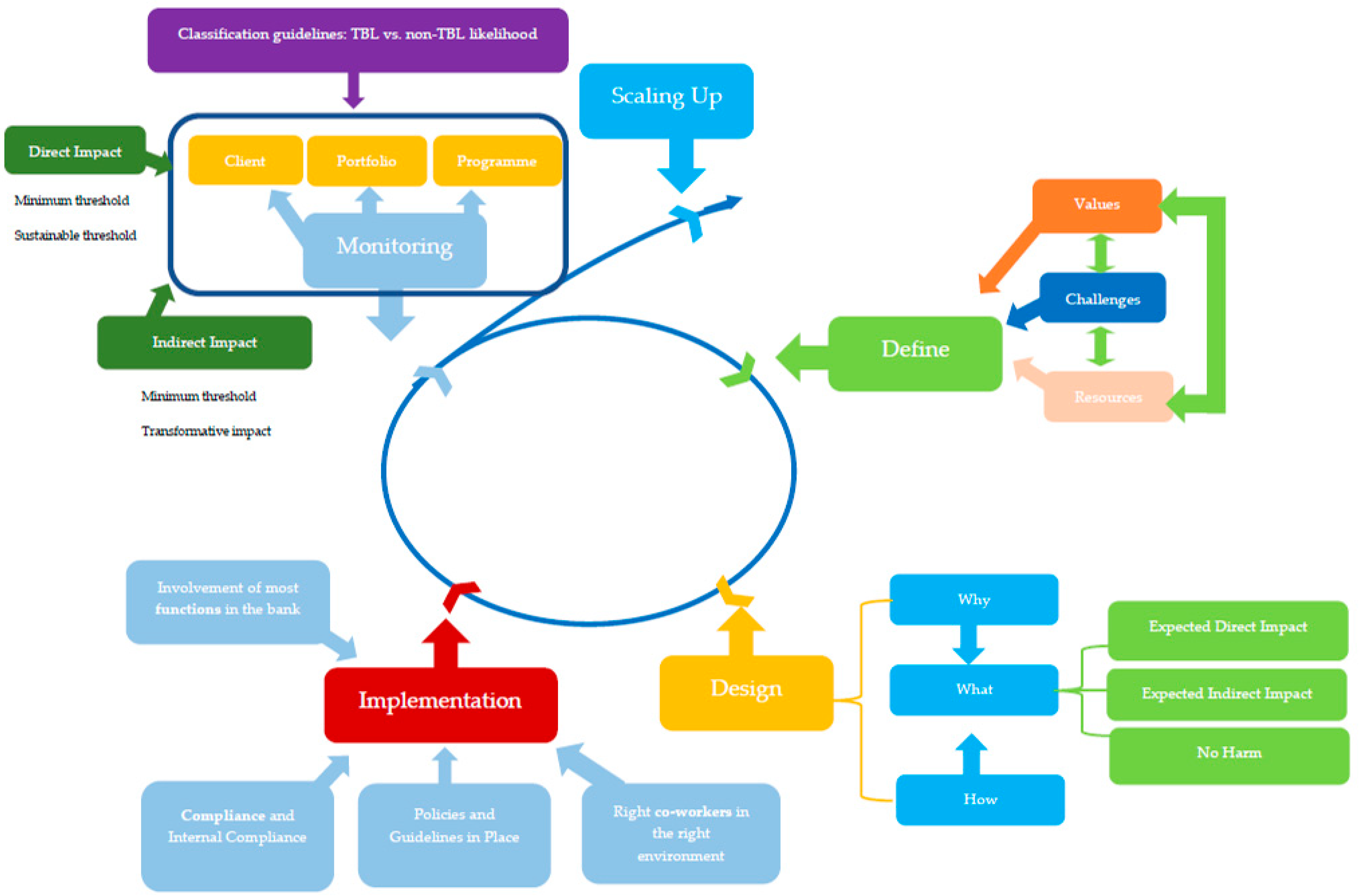

4.1. Practises Associated with the Definition Stage

- Values to inform decisions and the direction of travel;

- Social, economic and/or environmental challenges that need addressing;

- Resources in the hands of clients and communities enabled by the banking activity, i.e., jobs, health, education, basic infrastructure, housing, food and safety.

4.1.1. The “Values” Part of the Definition of Social Impact

4.1.2. The “Challenges” Part of the Definition of Social Impact

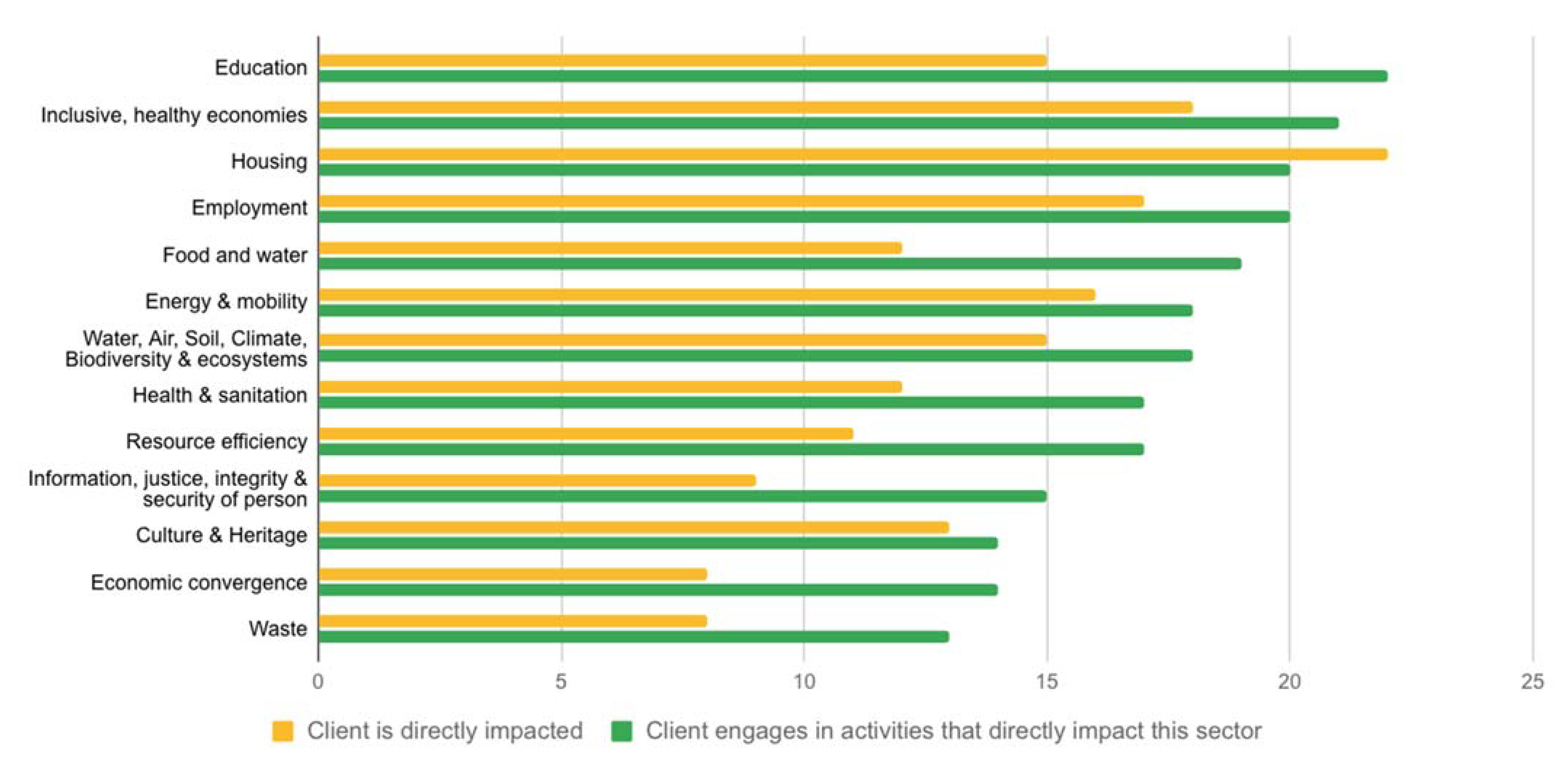

4.1.3. The “Resources” Part of the Definition of Social Impact

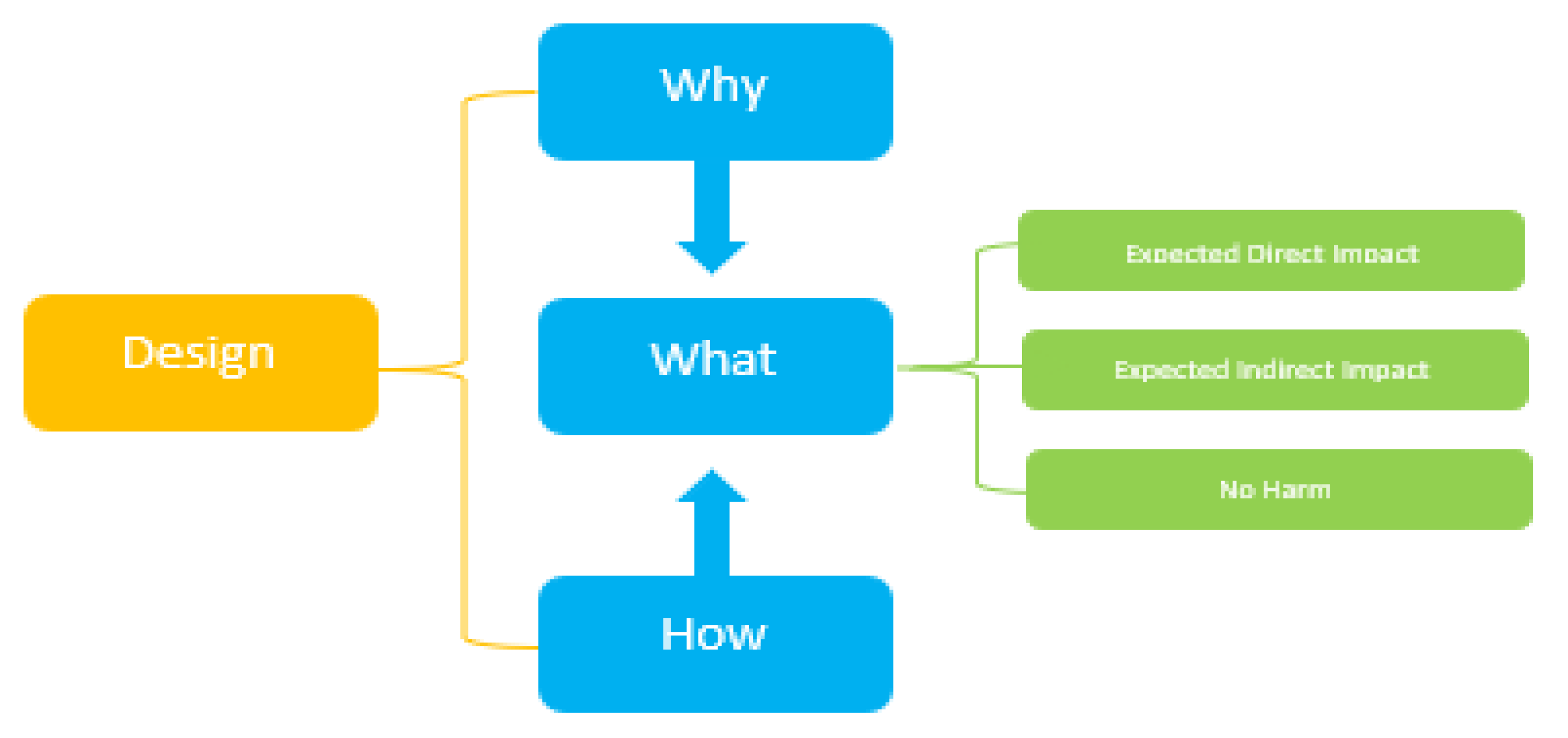

4.2. Practises Associated with the Design Stage

4.2.1. Social Impact Embedded by Design

4.2.2. Dimensions of Impact Design

4.2.3. Design That Prevents Locking-In Harm

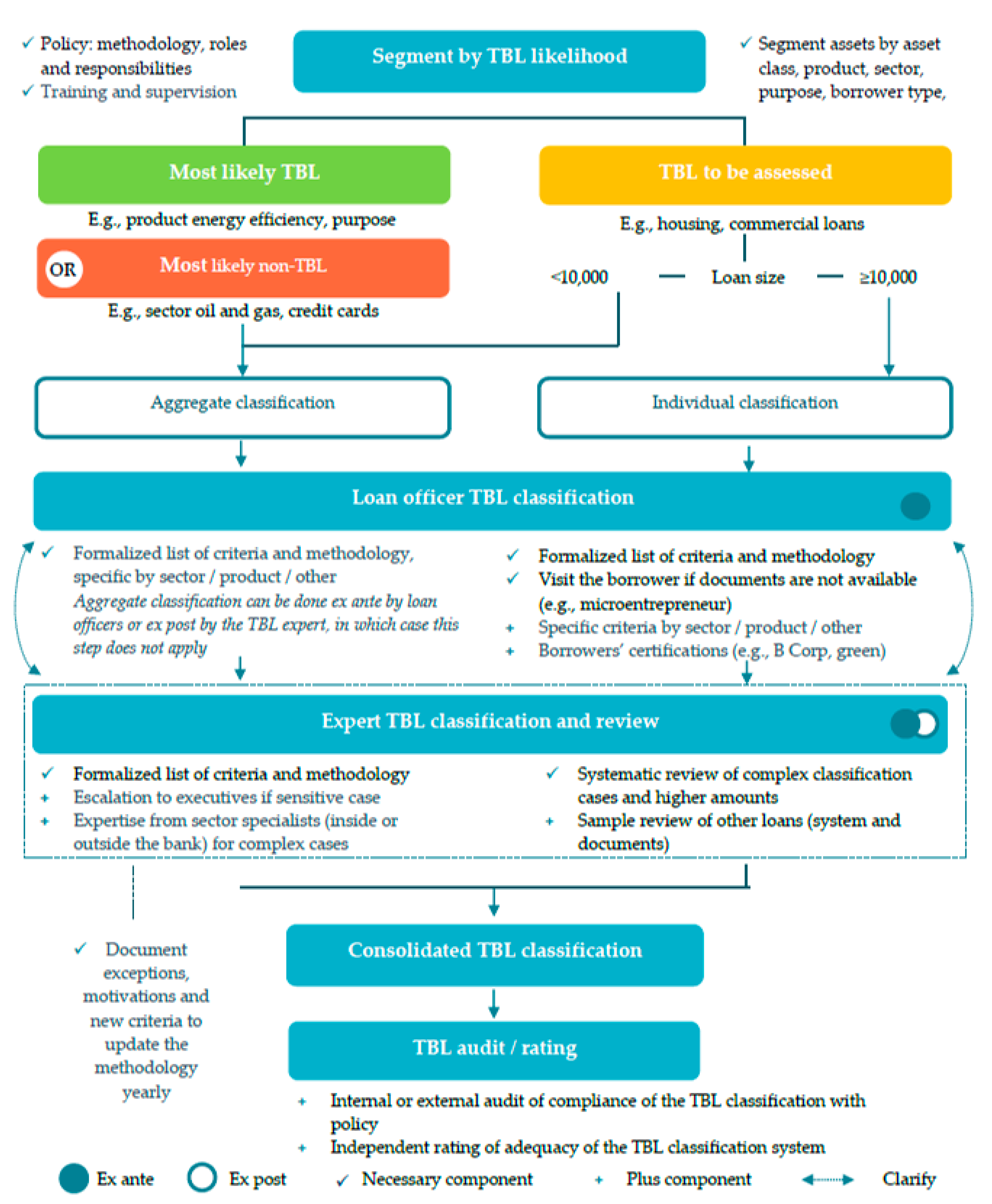

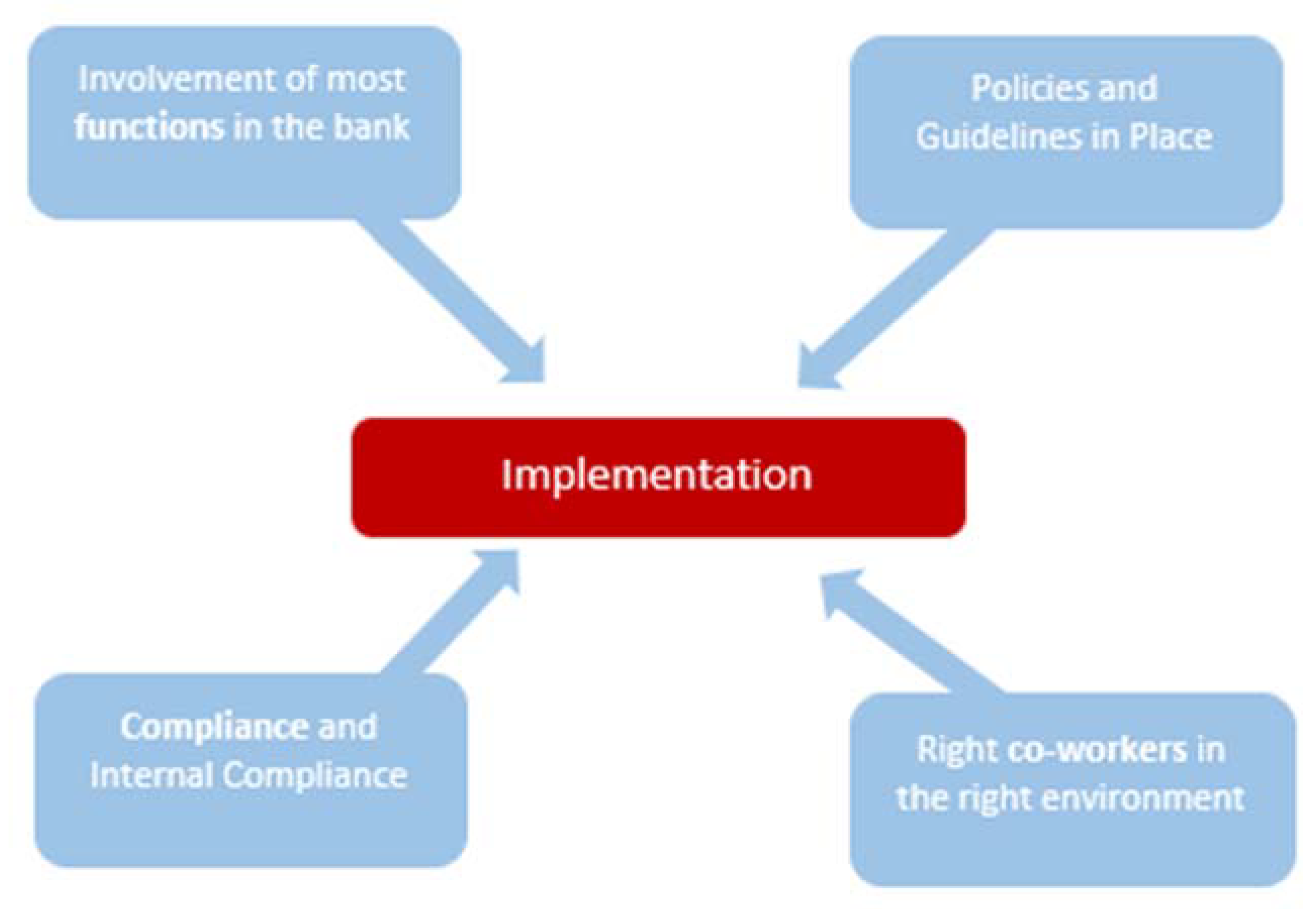

4.3. Practises Associated with the Implementation Stage

4.3.1. Social Impact: Not an Add-On

4.3.2. Tools to Support Coherent Decision Making

4.3.3. Organisational Change to Deliver Social Impact

4.3.4. Active Engagement

4.4. Practises Associated with the Monitoring Stage

4.4.1. Levels of Impact

4.4.2. Types of Monitoring

4.4.3. The Importance of the Process for Consistent Portfolio Monitoring

4.4.4. Indicators of Impact

4.5. Continuous Adjustment (Feedback Loop)

- In some cases, social challenges that affect a specific market are in themselves a limitation for growth and scaling-up impact;

- Regulatory constraints, such as credit risk concentration per sector or activity, might act as a clear limitation to scale-up impact even though the bank has processes and policies in place that would allow it to achieve a better position;

- The relative scarcity of resources of some values-based financial institutions prevent them from scaling-up social impact with more ambition;

- Attention to overall consistency to values makes joint transactions with banks or traditional operators rare although that could bring a significant increase in the impact market;

- Furthermore, in a limited number of cases the very same values of the bank itself restrict its activities to a niche, which makes scaling up more challenging.

- Firstly, the specificity of the market should not be understood to suggest that positive social impact is limited to certain sectors;

- Secondly, values-based financial institutions, although generally growing fast, are managed in a prudent and sound way, and this, in some sense, poses a limitation to faster growth. A strategic process of scaling-up is generally not planned by the single bank, but may be helped by external players.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Participating Financial Institutions

| 1 | Amalgamated Bank (USA) | 16 | Grooming Microfinance Bank (Nigeria) |

| 2 | Banca Etica (Italy) | 17 | Kindred Credit Union (Canada) |

| 3 | Banco Ademi (Dominican Republic) | 18 | Magnet Bank (Hungary) |

| 4 | Banco Popular de Honduras (Honduras) | 19 | MegaBank (Ukraine) |

| 5 | Bank Australia (Australia) | 20 | Clearwater Credit Union (USA) |

| 6 | Beneficial State Bank (USA) | 21 | Opportunity Bank Serbia (Serbia) |

| 7 | BRAC Bank (Bangladesh) | 22 | Southern Bancorp (USA) |

| 8 | Center-Invest (Russia) | 23 | Sunrise Banks (USA) |

| 9 | Cultura Bank (Norway) | 24 | The First Microfinance Bank-Afghanistan (Afghanistan) |

| 10 | Dai-Ichi Kangyo Credit Cooperative (Japan) | 25 | Triodos Bank (Europe) |

| 11 | Decorah Bank and Trust Co. (USA) | 26 | Umweltbank (Germany) |

| 12 | Ecology Building Society (United Kingdom) | 27 | Vancity Credit Union (Canada) |

| 13 | Freie Gemeinschaftsbank Genossenschaft (Switzerland) | 28 | Verity Credit Union (USA) |

| 14 | G&C Mutual Bank Limited (Australia) | 29 | Visión Banco (Paraguay) |

| 15 | GLS Bank (Germany) | 30 | VSECU (Vermont State Employees Credit Union) (USA) |

Appendix B. Questionnaire

- To realise its social impact objectives your institution has identified social needs and defined its social impact objectives. This section of the questionnaire is designed to understand how your institution defines social impact.

- What is social impact for my bank?

- My institution defines negative impact as

- My institution defines positive impact as

- How is your definition of social impact different from conventional banks? Please explain

- How does my bank measure social impact on client and by client? Please explain

- How does my institution capture the progress it makes in its social impact objectives? Please explain

- What information do we use to calibrate our social impact thresholds? That is, when is our intermediation socially sustainable and when does it go further and is socially transformative? Please explain

- What value does measuring social impact have for my bank and for its clients and communities? Please explain.

- What evidence of impact do I report and share with stakeholders? Please explain

- 8.

- What social challenges do your communities experience? Please select the top three only

| _____ | No poverty (Poverty) | _____ | Clean water and sanitation (Lack of …) | _____ | Sustainable cities and communities (Unsustainable …) | _____ | Peace, justice and strong institutions (Lack of …) |

| _____ | Zero hunger (Hunger) | _____ | Affordable and clean energy (Lack of …) | _____ | Responsible consumption and production (Irresponsible …) | _____ | Partnerships for the goals (removed) |

| _____ | Good health and well-being (Poor …) | _____ | Decent work and economic growth (Lack of …) | _____ | Climate action (Lack of …) | _____ | Race and age discrimination |

| _____ | Quality education (Low …) | _____ | Industry innovation and infrastructure (Lack of …) | _____ | Life below water (Threat to …) | _____ | Other (please specify) |

| _____ | Gender equality (Gender inequality) | _____ | Reduced inequalities (Growing …) | _____ | Life on land (Threat to …) | _____ |

- 9.

- Select only three, then rank order: What are your institution’s top three priority social values informing your product design and offerings, as well as business practises (please rank order 1–3 with 1 being your top priority and 3 the third?

| _____ | VALUES |

| _____ | Human dignity |

| _____ | Fairness |

| _____ | Inclusion |

| _____ | Solidarity |

| _____ | Affordability |

| _____ | Resilience |

| _____ | Well-being |

| _____ | Happiness |

| _____ | Diversity |

| _____ | Honesty |

| _____ | No speculation |

| _____ | No corruption |

| _____ | Co-responsibility |

| _____ | Financial freedom |

| __________ | Other: |

- 10.

- If you selected “Other” in the previous question, please explain:

- 11.

- Select only three, then rank order: What are your institution’s top three priority social objectives informing your product design and offering, as well as business practises (please rank order 1–3 with 1 being your top priority and 3 the third)? (23)

| _____ | OBJECTIVES |

| _____ | Jobs |

| _____ | Equitable access to housing |

| _____ | Equitable access to food |

| _____ | Equitable access to healthcare |

| _____ | Equitable access to education |

| _____ | Equitable access to basic infrastructure |

| __________ | Other: |

- 12.

- If you selected “Other” in the previous question, please explain:

- 13.

- Your institution offers products and services to clients operating in the following dimensions of well-being (check all that apply):

| Client Is Directly Impacted | Client Engages in Activity That Directly Impacts These Sectors | |

| Social | _____ | _____ |

| Food and water | _____ | _____ |

| Housing | _____ | _____ |

| Health and sanitation | _____ | _____ |

| Education | _____ | _____ |

| Employment | _____ | _____ |

| Energy and mobility | _____ | _____ |

| Culture and Heritage | _____ | _____ |

| Information, justice, integrity and security of person | _____ | _____ |

| Economic | _____ | _____ |

| Inclusive, healthy economies | _____ | _____ |

| Economic convergence | _____ | _____ |

| Environmental | _____ | _____ |

| Resource efficiency | _____ | _____ |

| Waste | _____ | _____ |

| Water, air, soil, climate, biodiversity and ecosystems | _____ | _____ |

| Other (please specify): | ___________________ | ___________________ |

- Your responses to the questions in this section give you an opportunity to elaborate on your institution’s unique designed approach to realizing its social impact priorities. Please respond to these questions through the approach that is most relevant to your institution (see question 14)

- 14.

- Please select the statement that best describes your institution’s approach to social impact (select only one):

| _____ | My approach to social impact is best described as responding to the challenges selected in question 8 above |

| _____ | My approach to social impact is best described as advancing the social values selected in question 9 above |

| _____ | My approach to social impact is best described as advancing the social objectives selected in question 11 above |

| _____ | My approach to social impact is best described as advancing the dimensions of well-being selected in question 13 above |

- 15.

- My institution is confident that its products and services advance its social impact targets for the following reasons (rank order from most important to least important (with 1 being the highest and 6 the lowest):

| _____ | Impact targets are embedded in product and service design |

| _____ | We do not finance sectors that are harmful |

| _____ | We measure and report progress using our own indicators |

| _____ | Our strategy, processes and actions are designed to deliver on social impact objectives |

| _____ | My institution has a “do no harm” policy (please include) |

| _____ | My institution relies on an exclusion list based on internationally conventions and activities commonly recognised as harmful (please include) |

| _____ | Other |

- 16.

- If you selected “Other”, please explain:

- 17.

- Impact target design by my institution is driven by one or more of the following in order of importance (with 1 being the highest and 5 lowest):

| _____ | Asset classes (e.g., commercial real estate, mortgages, business loans) |

| _____ | Economic sector (agriculture, manufacturing, etc.) |

| _____ | Client personal characteristics (e.g., race, gender, employment) |

| _____ | Meets basic needs of community (e.g, access to sanitation, housing) |

| _____ | Quality of life indicators (e.g., material living conditions, productive or main activity, health, education, leisure, economic security and physical safety, governance and basic rights, natural and living environment, overall experience of life) |

| _____ | Other (please describe): |

- 18.

- If you selected “Other”, please describe:

- 19.

- Please rank order your current social impact target customer groups (1 is most targeted and 6 least targeted):

| Start-ups without an organisational structure | _____ |

| Micro enterprises (below 10 employees) | _____ |

| Small enterprise (below 50 employees) | _____ |

| Medium enterprises (below 250 employees) | _____ |

| Large enterprises with 250 employees or above | _____ |

| Individual customers | _____ |

| Other (please explain) | _______________ |

- 20.

- If you selected “Individual customers”, please describe them

- 21.

- If you selected “Other”, please explain

- 22.

- What factors are important in the design of products that deliver social impact. For each product (column), please rank order your responses 1–8, with 1 being the most relevant to 8 being the least relevant:

| Type of Product | Current Accounts | Savings Accounts | Microfinance | Short-Term Loans | Long-Term Loans | Mortgages | Financial Advice | Investment Products |

| Asset classes | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ |

| Sector | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ |

| Client personal characteristics | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ |

| Client type of activity | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ |

| Meets basic needs of the community | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ |

| Quality of life indicators | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ |

| No specific social impact objective exists for this product | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ |

| Other | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ | _____ |

| Other (please specify) | ||||||||

- 23.

- Products and services are designed upfront to do no harm and your institution provides evidence that they do no harm in practise

- Your institution has developed an approach to delivering on its social impact priorities. The following questions are designed to capture the key elements of this approach with a focus on your top three social impact priorities (as indicated in your answer to question 14):

- 24.

- What percent of co-workers are dedicated to advancing the social impact priorities of your institution (please give your best estimate)?

| _____ | Less than 10% |

| _____ | Around 25% |

| _____ | Approximately 50% |

| _____ | Close to 75% |

| _____ | Pretty much everyone |

- 25.

- Which departments in your institution are responsible for delivering on your institution’s social priorities?

- 26.

- How do these departments contribute to advancing social benefits for its clients and other stakeholders? If protocols and/or checklists are used, please send these to adriana.kocornik@gabv.org with the subject line “q26 checklists”.__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 27.

- How does your institution resolve trade-offs that arise because of regulatory and/or business tensions when advancing its social impact priorities?

- 28.

- My institution has defined guidelines on how to resolve potential ethical dilemmas and trade-offs involving risk, return and impact considerations that reflect its level of tolerance. Please send these guidelines to adriana.kocornik@gabv.org subject line “q28 guidelines”.

| Yes | _____ |

| No | _____ |

| Other (please specify) | _______________________________________________________________________________________________ |

- 29.

- Does your institution have systems in place to track progress on meeting social priorities?

- 30.

- If yes, are these your own systems or are these provided by a third party (please include the name of the third party)?

- 31.

- Do you use certifications or labels to support your decision making and ensure the delivery of social impact priorities?

- 32.

- If yes, please list these certification or labels:

- 33.

- Is progress on social impact priorities part of your internal due diligence?

- 34.

- If yes, please describe how:

- 35.

- Does your institution have social impact targets that are monitored by the Board?

- 36.

- If yes, please state what it is:

- 37.

- Is your internal audit department carrying out its risk assessment of the bank taking into account its performance on social impact factors and/or reputational risk?

- 38.

- If yes, please elaborate:

- 39.

- Has your institution been evolving your business practises in order to deliver on its social impact priorities?

- 40.

- If you answered yes, please describe the changes in your organisation:

- 41.

- My institution is coherent in its commitment to social impact priorities as it has (please select all that apply):

| _____ | Gender balance in wages |

| _____ | Dignity and safety: better co-working environment |

| _____ | Encourage innovation |

| _____ | Other (Please specify) |

- 42.

- For managers and co-workers, do you connect variable wages not just to economic performance indicators but also to social impact results?

- 43.

- If yes, please describe how:

- Your institution may have developed an approach to monitoring progress in delivering its social impact priorities. The following questions are designed to capture the key elements of this approach with a focus on your top three priorities as indicated in your answer to question 14:

- 44.

- My institution monitors progress on delivering social targets with a focus on (select only one):

| _____ | Economic sector |

| _____ | Asset class |

| _____ | Quality of life indicators |

| _____ | Individual and/or type of organisation |

| _____ | Other (please specify) |

- 45.

- My institution monitors progress in delivering on the institution’s social impact priorities for the following asset classes (Yes/No for all that apply)

| Asset Class | Portfolio-Level | Client-Level |

| Listed equity and corporate bonds | _____ | _____ |

| Business loans and unlisted equity | _____ | _____ |

| Project finance | _____ | _____ |

| Commercial real estate | _____ | _____ |

| Mortgages | _____ | _____ |

| Motor vehicle loans | _____ | _____ |

| Other | _____ | _____ |

| Other (please explain): | _________________________________________________________________ | |

- 46.

- If appropriate, please list the indicators used to track progress on your institution’s social impact priorities by relevant customer group:

| Start-Ups without an Organisational Structure | |

| Micro enterprises (below 10 employees) | _________________________________________________________________ |

| Small enterprise (below 50 employees) | _________________________________________________________________ |

| Medium enterprises (below 250 employees) | _________________________________________________________________ |

| Large enterprises with 250 employees or above | _________________________________________________________________ |

| Individual customers | _________________________________________________________________ |

| Other (please define customer group) | _________________________________________________________________ |

- 47.

- How would you rate the precision of the data your institution has to track progress on its social impact priorities?

| Precise | Imprecise | |

| Asset classes | _____ | _____ |

| Economic sector | _____ | _____ |

| Client personal characteristics | _____ | _____ |

| Meets basic needs of community | _____ | _____ |

| Quality of life indicators | _____ | _____ |

| Other (please describe): | _________________________________________________________________ | |

- 48.

- Please enter AGREE only for those statements that most appropriately describe your institution’s current approach to measuring its positive social impact:

| i. | Minimum: My institution counts its activities as creating positive social impact IF they provide financial ACCESS to underserved populations |

| Please provide your definition of what constitutes underserved population: | |

| ii. | Sustainable: My institution counts its activities as creating positive social impact IF they provide financial access to underserved populations AND do not significantly harm the environment |

| Please define what no significant harm means for your institution | |

| i. | Minimum: My institution counts its activities as positive social impact ONLY if its clients provide services to underserved populations (answer for one option only): |

| ii. | …that would otherwise NOT be available to the underserved population |

| iii. | …that are ALREADY available to the underserved population |

| iv. | Minimum: My institution counts its activities as positive social impact only when it addresses MULTIPLE and INTERSECTING challenges faced by its clients (please respond with your answer to question 8 in mind) |

| v. | Sustainable: When addressing intersectionality of challenges only those with multiple challenges AND that meet no harm criteria qualify as social impact |

| vi. | Minimum: My institution ONLY counts its activities as positive social impact if it finances SMEs that create or protect jobs |

| vii. | Sustainable: My institution ONLY counts its activities as positive social impact if it finances SMEs that create or protect jobs AND do not significantly harm the environment |

| Please define what no significant harm means for your institution when applied to SMEs | |

| viii. | Transformative: My institution ONLY counts its activities as positive social impact if its clients are transforming their business activities to sustainably deliver social impact AND do not significantly harm to the environment |

| Please provide one example: | |

- 49.

- If my institution is no longer active in the market, the following stakeholders would be negatively impacted

| Negatively | Positively | |

| Individuals in my community | _____ | _____ |

| Enterprises in my community | _____ | _____ |

| Other financial institutions | _____ | _____ |

| NGOs in my community | ||

| Local government actors | _____ | _____ |

| Other | _____________ | ____________________ |

| Other (please specify) | ||

- 50.

- Please describe what elements informed your response to question 49

- Before you go, please tell us a little bit about yourself and your institution. Thank you once again for your support and for your valuable inputs.

- 51.

- Your name

- 52.

- Your role

- 53.

- Your email

- 54.

- Your institution’s name

- 55.

- Your institution’s mission

- 56.

- How many employees work in your bank?

- below 50

- 50–99

- 100–249

- over 250

- 57.

- Regions of operation (please list countries, states or cities as appropriate)

- 58.

- Looking at your institution’s efforts and intentions during the last 3 years, please rank order from most (1) to least (4) efforts and intentions allocated:

| Category | Rank Order |

| Financial returns for investors | _____ |

| Economic resiliency for clients and communities | _____ |

| Environmental regeneration for clients and communities | _____ |

| Social empowerment for clients and communities | _____ |

| Other | _____ |

- 59.

- If you selected “Other’ in the previous question, please explain:

- 60.

- To the best of my knowledge, my institution’s business practises and product offerings are in compliance with regulations and norms that protect (please select all that apply):

| _____ | Human rights |

| _____ | Labour rights |

| _____ | Customer privacy |

| _____ | Data security |

| _____ | Access and affordability |

| _____ | Selling practises and product labelling |

| _____ | Employee engagement, diversity and inclusion (social capital/SASB) |

| _____ | Product design and lifecycle management |

| _____ | Physical impacts of climate change |

| _____ | Systemic risk management |

| _____ | Business ethics |

| _____ | Other (please specify) |

- 61.

- Looking at your institution’s total number of banking services sold as of December 2020, what percent of your core business is accounted by the following banking services (Please provide your best estimate (must add to 100%))?

| Banking Services | Percent of Total Number of Banking Services Sold |

| Current accounts | _____ |

| Savings accounts | _____ |

| Microfinance | _____ |

| Consumer loans | _____ |

| Business loans | _____ |

| Mortgages | _____ |

| Investment products | _____ |

| Other | _____ |

- 62.

- If you selected “Other” in the previous question, please explain:

- 63.

- If there is anything else you would like to share with us, please enter it here:

Appendix C. CEO Interview Protocol

Appendix C.1. The VALoRE Project

Overview and Background

Appendix C.2. Why the EU Taxonomy?

Appendix C.3. Interview Protocol

- Define and Design: The social impact objectives that you and your institution have, including your target sectors/activities, clients.

- Implement: Your strategic approach to deliver on these social impact objectives, including how you prioritise and address potential trade-offs, and your business processes and oversight.

- Monitor: Your performance, including criteria, assessment and reporting.

Appendix C.4. Selected Questions for CEOs

- What is the dream you and your institution have for your clients and communities? Please note if this dream is in response to the challenges your clients and communities face, and/or opportunities in your market.

- How does your bank help achieve that dream? Please provide 2–3 concrete examples. These may include business practises you have put in place, the tools you rely upon to make decisions, how you address trade-offs and whom do you partner with.

- What values inform your decisions? How do you translate these values into actual and measurable outcomes?

- How do you know you are doing very well or very little? How far down your supply chain do you investigate to assess your impact? That is, do you examine your clients’ role in, for example, helping others to fulfil basic human needs, including the availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of water and food, healthcare, housing and education?

- What information do you rely upon to decide to scale-up your impact? How do you address barriers?

Appendix C.5. Background Reading

Appendix C.6. Recording

References

- United Nations Sustainable Goals. Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Chen, S.; Ravallion, M. More Relatively-Poor People in a Less Absolutely-Poor World. Policy Research Working Paper 611. 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11876 (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights. 2016. Available online: https://srpovertyorg.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/social-and-economic-as-human-rights-report-2016.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- 2020 Social Progress Index. Available online: https://socialprogress.blog/2020/09/10/announcing-the-2020-social-progress-index/ (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Sustainable Development. The Sustainable Development Agenda. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative. UNEP FI: Principles for Responsible Banking; Guidance Document; UNEP Finance Initiative: Geneva, Switezerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/PRB-Reporting-Guidance-Document.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Fatemi, A.M.; Fooladi, I.J. Sustainable Finance: A New Paradigm. Glob. Financ. J. 2013, 24, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingales, L.; Kasperkevic, J.; Schechter, A. Milton Friedman 50 Years Later; Stigler Center: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinall, N.G.; Jones, S.R.; McNeill, E.H.; Werner, R.A.; Zalk, T. Sustainability and the Financial System Review of Literature 2015. Br. Actuar. J. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carolina Rezende de Carvalho Ferrei, M.; Amorim Sobreiro, V.; Kimura, H.; Luiz de Moraes Barboza, F. A Systematic Review of Literature about Finance and Sustainability. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2016, 6, 112–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KKS Advisors. Do Sustainable Banks Outperform? Driving Value Creation through ESG Practices. 2019. Available online: http://www.gabv.org/wp-content/uploads/Do-sustainable-banks-outperform.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Pisano, U.; Martinuzzi, A.; Bruckner, B. The Financial Sector and Sustainable Development: Logics, Principles and Actors; EDSN: Vienna, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fullwiler, S.T. Sustainable Finance: Building a More General Theory of Finance. Global Institute for Sustainable Prosperity Working Paper No. 106. 2015. Available online: http://www.global-isp.org/wp-content/uploads/WP-106.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- United Nation. Report on the World Social Situation. Bureau of Social Affairs, Social Development; Department for Economic, Social Information, & Policy Analysis, United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dugarova, E. Social Inclusion, Poverty Eradication and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (No. 2015-15); UNRISD Working Paper; UNRISD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.unrisd.org/unrisd/website/document.nsf/(httpPublications)/0E9547327B7941D6C1257EDF003E74EB?OpenDocument (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Ozili, P.K. Social Inclusion and Financial Inclusion: International Evidence. Int. J. Dev. Issues 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibba, M. Financial inclusion, poverty reduction and the millennium development goals. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2009, 21, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, V. Reaching sustainable development goals: Bringing financial inclusion to reality in India. J. Public Aff. 2020, 20, e2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Dupas, P. Constraints to Saving for Health Expenditures in Kenya. 2011. Available online: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/evaluation/constraints-saving-health-expenditures-kenya (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Brune, L.; Giné, X.; Goldberg, J.; Yang, D. Facilitating savings for agriculture: Field experimental evidence from Malawi. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2016, 64, 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Sustainable Finance Action Plan. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance_en (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Schoenmaker, D. Investing For The Common Good: A Sustainable Finance Framework; Bruegel: Brussels, Belguim, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ziolo, M.; Filipiak, B.Z.; Bąk, I.; Cheba, K.; Tîrca, D.M.; Novo-Corti, I. Finance, Sustainability and Negative Externalities. An Overview of the European Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative. Rethinking Impact to Finance the SDGs. A Position Paper and Call to Action Prepared by the Positive Impact Initiative. 2018. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Rethinking-Impact-to-Finance-the-SDGs.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Nizam, E.; Ng, A.; Dewandaru, G.; Nagayev, R.; Nkoba, M.A. The impact of social and environmental sustainability on financial performance—A global analysis of the banking sector. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2020, 49, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Acc. Rev. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative. The Principles for Positive Impact Finance. A Common Framework to Finance the Sustainable Development Goals. 2017. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/POSITIVE-IMPACT-PRINCIPLES-AW-WEB.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance. Taxonomy Technical Report. Financing a Sustainable European Economy. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/190618-sustainable-finance-teg-report-taxonomy_en.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Nedopil Wang, C.; Lund Larsen, M.; Wang, Y. Addressing the Missing Linkage in Sustainable Finance: The ‘SDG Finance Taxonomy’. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.; Boonstra, J. Leadership and Organizational Culture Based on Sustainable Innovational Values: Portraying the Case of the Global Alliance for Banking Based on Values (GABV). ESADE Business School Working Paper No. 270. 2018. Available online: https://www.sioo.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Leadership_and_organizational_culture_based_on_sustainable_innovational_values.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Nosratabadi, S.; Pinter, G.; Mosavi, A.; Semperger, S. Sustainable Banking, Evaluation of the European Business Models. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, J.; Cabaj, M. Social Return on Investment. Mak. Waves 2000, 11. Available online: https://auspace.athabascau.ca/bitstream/handle/2149/1028/MW110210.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Clark, C.; Rosenzweig, W.; Long, D.; Olsen, S. Double Bottom Line Project Report: Assessing Social Impact in Double Bottom Line Ventures. Working Paper, 13. 2004. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/paper-rosenzweig.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Maas, K.; Liket, K. Social Impact Measurement: Classification of Methods. In Environmental Management Accounting and Supply Chain Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burdge, R.J.; Vanclay, F. Social Impact Assessment: A Contribution to the State of the Art Series. Impact Assess. 1996, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, M. Social Impact Management: A Definition, Business and Society program. The Aspen Institute Business and Society Program Discussion Paper No. 11. 2002. Available online: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/files/content/docs/bsp/SOCIALIMPACTMANAGEMENT.PDF (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Vanclay, F. International Principles For Social Impact Assessment. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2003, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative. Positive Impact Finance. A Common Vision for the Financing of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Brussels, 2015. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/POSITIVE-IMPACT-MANIFESTO-NEW-1.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Global Alliance for Banking on Values. What Are Principles of Values-Based Banking? Available online: https://www.gabv.org/wp-content/uploads/Prinicples-of-Values-based-Banking.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Migliorelli, M. What Do We Mean by Sustainable Finance? Assessing Existing Frameworks and Policy Risks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP FI. The Impact Radar: A Tool for Holistic Impact Analysis, Brussels, 2018. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/PI-Impact-Radar.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2021).

- De Clerck, F. Ethical Banking. In Ethical Prospects; Zsolnai, L., Boda, Z., Fekete, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Carè, R. Sustainable Banking; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, Y.; Magezi, E.F. The Impact of Microcredit on Agricultural Technology Adoption and Productivity: Evidence from Randomized Control Trial in Tanzania. World Dev. 2020, 133, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, S.A.; Ratinger, T.; Ahado, S. Has Microcredit Boosted Poultry Production in Ghana? Agric. Financ. Rev. 2019, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imeson, M.; Sim, A. Sustainable Banking: Why Helping Communities and Saving the Planet Is Good for Business? SAS White Paper; SAS Institute Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stankeviciene, J.; Nikonorova, M. Sustainable Value Creation in Commercial Banks During Financial Crisis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 110, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O.; Feltmate, B. Sustainable Banking; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abad Segura, E.; del Carmen Valls Martínez, M. Análisis Estratégico de La Banca Ética En España a Través de Triodos Bank. Financiación de Proyectos Sociales y Medioambientales. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa 2018, No. 92. Available online: https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/ciriecespana/article/view/10805 (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Chew, B.C.; Tan, L.H.; Hamid, S.R. Ethical Banking in Practice: A Closer Look at the Co-Operative Bank UK PLC. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Chew, B.; Hamid, S. A Holistic Perspective on Sustainable Banking Operating System Drivers: A Case Study of Maybank Group. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2017, 9, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Charity Bank Limited. Measuring Social Impact: Our Approach. A Brief Guide to How and Why We Measure Social Impact; Charity Bank: Tonbridge, UK, 2015; Available online: https://charitybank.org/uploads/files/Social-Impact-Statement-2015.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Epstein, M.; Buhovac, A. Making Sustainability Work: Best Practices in Managing and Measuring Corporate Social, Environmental, and Economic Impacts; Greenleaf Publishing Limited: Sheffield, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Burritt, R.L.; Hahn, T.; Schaltegger, S. Towards a Comprehensive Framework for Environmental Management Accounting—Links between Business Actors and Environmental Management Accounting Tools. Aust. Acc. Rev. 2002, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Garcia, M.M.; Trovato, G. Credit Rationing and Credit View: Empirical Evidence from an Ethical Bank in Italy. J. Money Credit Bank. 2011, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, M.; Langella, V.; Bramanti, V. Review of Impact Assessment Methodologies for Ethical Finance. 2015. Available online: https://www.socioeco.org/bdf_fiche-document-3714_en.html (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Bonini, S.; Emerson, J. Maximizing Blended Value—Building beyond the Blended Value Map to Sustainable Investing, Philanthropy and Organizations. Available online: https://staging.community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/report-bonini3.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Antony, J.; Gupta, S. Top Ten Reasons for Process Improvement Project Failures. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.K.; Prescott, J.E. Variations in Critical Success Factors Over the Stages in the Project Life Cycle. J. Manag. 1988, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.; Ward, S. Project Risk Management, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barberá, L.; Crespo, A.; Viveros, P.; Stegmaier, R. Advanced Model for Maintenance Management in a Continuous Improvement Cycle: Integration into the Business Strategy. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2012, 3, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatchalian, M.M. People Empowerment: The Key to TQM Success. TQM Magazine, 1 December 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Kaviani, M.A.; Galli, B.J.; Ishtiaq, P. Application of Continuous Improvement Techniques to Improve Organization Performance. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Assen, M.F. Empowering Leadership and Contextual Ambidexterity—The Mediating Role of Committed Leadership for Continuous Improvement. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollweck, T. Robert K. Yin. (2014). Case Study Research Design And Methods (5th Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 282 Pages. Can. J. Progr. Eval. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Two Decades of Developments in Qualitative Inquiry. Qual. Soc. Work 2002, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Social Banking: Concept, Definitions and Practice. Glob. Soc. Policy 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, J. Managing Strategic and Cultural Change in Organizations. J. Financ. Transform. 2021, 52, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Global Alliance for Banking on Values. Real Economy—Real Returns: The Business Case for Values-Based Banking. 2020. Available online: https://www.gabv.org/news/real-economy-real-returns-the-business-case-for-values-based-banking (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Schäfer, T.; Utz, S. Values-Based and Global Systemically Important Banks: Their Stability and the Impact of Regulatory Changes after the Financial Crisis on It. Asia-Pac. Financ. Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.; Plano Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Jose, L.; Retolaza, J.L.; Gutierrez-Goiria, J. Are Ethical Banks Different? A Comparative Analysis Using the Radical Affinity Index. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triodos Bank. Annual Report 2017. Available online: https://www.triodos.com/binaries/content/assets/tbho/annual-figures/triodos-bank-annual-report-2017.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Kay, J. Other People’s Money; Profile Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Benchmarking Alliance. Financial System Transformation Scoping Report. 2021. Available online: https://assets.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/app/uploads/2021/01/WBA-Financial-System-Transformation-Scoping-Report-January-2021-WEB.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Impact Institute. Impact Measurement and Valuation for Banks. Available online: https://www.impactinstitute.com/impact-measurement-and-valuation-for-banks/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Deeper and Fairer Economic and Monetary Union, European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/priorities/deeper-and-fairer-economic-and-monetary-union/european-pillar-social-rights/european-pillar-social-rights-20-principles_en (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Bank Australia. Our Responsible Banking Policy. Available online: https://www.bankaust.com.au/globalassets/assets/reporting-governance--policies/policies-plans--positions/responsible-banking-policy/responsible-banking-policy-statement.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Scott, J.M.; Hussain, J. Exploring Intersectionality Issues in Entrepreneurial Finance: Policy Responses and Future Research Directions. Strateg. Chang. 2019, 28, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsem, K. Bankruptcy Reform and the Financial Well Being of Women: How Intersectionality Matters in Money Matters. Brooklyn Law Rev. 2006, 71, 1181. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza-Chock, S. Design Justice: Towards an intersectional feminist framework for design theory and practice. In Proceedings of the DRS International Conference—Design as a Catalyst for Change, Limerick, Ireland, 25–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, K.; Schuster, B.; Rankin, S. Discrimination at the Margins: The Intersectionality of Homelessness & Other Marginalized Groups. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 1, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- GABV’s COVID-19 Resource Hub. GABV Members Responses to the Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.gabv.org/covid-19-resource-hub (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- GLS Bank. Anlage und Finanzierungsgrundsätze. Available online: https://www.gls.de/media/PDF/Broschueren/GLS_Bank/gls_anlage-und_finanzierungsgrundsaetze.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Beneficial State. Mission Principles and Policies. Available online: https://impact.beneficialstate.org/mission-principles-and-policies/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Triodos Bank. Minimum Standards. 2018. Available online: https://www.triodos.com/downloads/about-triodos-bank/triodos-banks-minimum-standards.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Triodos Bank. Business Principles. 2016. Available online: https://www.triodos.com/binaries/content/assets/tbho/corporate-governance/triodos-bank-business-principles.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- NRB News. NRB Releases Monetary Policy for FY 2020-21. Publication of the Central Bank of Nepal. Volume 41. Available online: https://www.nrb.org.np/contents/uploads/2020/12/NRB-News-Vol.40-20770818.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Reporte di Impatto 2020. Insieme, Facciamo Crescere una Nuova Economia, Banca Etica, 2020. Available online: https://bancaetica.it/report-impatto-2019/pdf/Report_impatto_ITA.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

| Business Model | Count * | Region | Assets on the Balance Sheet and under Management (US$ Millions) | Co-Workers | Clients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFI | 6 (18) | Africa, Asia Pacific, Europe, Latin America | 4313 | 12,113 | 2,049,036 |

| OT | 6 (8) | Asia, Europe, North America | 7781 | 624 | 224,245 |

| RB | 11 (21) | Asia, Europe, Latin America, North America | 84,614 | 5975 | 2,730,036 |

| SL | 7 (14) | Asia, Europe, North America | 41,849 | 4743 | 1,418,916 |

| Total | 30 (61) | 138,556 (169,810) | 23,455 (58,207) | 6,422,233 (19,188,030) |

| 1. | Banca Etica (Italy, 2009) | 6. | Magnet Bank (Hungary, 2016) |

| 2. | Banco Popular de Honduras (Honduras, 2018) | 7. | Southern Bancorp (USA, 2015) |

| 3. | Center-Invest (Russia, 2019) | 8. | Sunrise Banks (USA, 2011) |

| 4. | Dai-Ichi Kangyo Credit Cooperative (Japan, 2018) | 9. | Triodos Bank (Europe, 2009) |

| 5. | GLS Bank (Germany, 2009) | 10. | Vancity (Canada, 2010) |

| Current Accounts | Microfinance | Business Loans | Consumer Loans | Mortgage | Financial Advice | Investment Products | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Client type of activity | 17% | 13% | 4% | 19% | 30% | 11% | 8% |

| Sector | 11% | 17% | 27% | 14% | 15% | 5% | 33% |

| Asset classes | 0% | 13% | 23% | 10% | 15% | 21% | 25% |

| Client personal characteristics | 39% | 9% | 15% | 14% | 15% | 16% | 8% |

| Meets basic needs of the community | 6% | 13% | 19% | 19% | 15% | 11% | 17% |

| Quality of life indicators | 11% | 35% | 12% | 24% | 10% | 32% | 8% |

| No specific social impact objective exists for this product | 17% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 0% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Monthly reports on loan distribution in economic sectors |

| Quarterly impact appetite framework [93] built using 23 indicators in the areas of environment, social, governance, peace and ethical finance |

| Quarterly reports on organisational and management targets including social and environmental aspects |

| TBL assets (see portfolio monitoring below), # of volunteer hours of employees, % of employees volunteering, money provided in contribution or sponsorship to non-profit organisations |

| Oversight of institution’s CSR actions |

| Number of loans that reach the poor, impact of loans on the environment, targeting regions where there are unbanked segments of the population |

| Progress on the impact measurement and development of the GABV Scorecard |

| Share of impact finance assets to total assets |

| Proportion of mortgage lending on community housing |

| Outreach to rural loan clients, low-income clients, underbanked clients, plus jobs created by agriculture and business loans |

| Customer Group | Minimum | Additional |

|---|---|---|

| Start-ups without an organisational structure | Jobs created (output) | Jobs retained |

| Clients funded (output) | Clients supported in formulation of business start-up plans Referrals to government-affiliated financial institutions for start-up support | |

| Income of borrower as percent of average median income (input) | ||

| Micro, small and medium enterprises | Share of loans to micro enterprises in portfolio (output) | |

| Number served by programme (output) | Cases of main business support Cases of business succession support Cases of M&A support | |

| Ownership by underserved clients, women, people of colour (input) | ||

| Organisational structure is mission-focussed (non-profit, cooperative, etc.) (input) | ||

| Corporate practises including no corruption and compliance with labour laws (input) | Hiring practises for disadvantaged groups (input) | |

| Sector including housing, education, healthy food, etc. (input) | Transactions | |

| Large enterprises (≥250 employees) | All of the above plus: Loans and advances (input) | |

| Quality of trade portfolios (input) | ||

| Compliance | ||

| Digitisation | ||

| Individual customers | Share of rural clients or other low-income areas (output) | |

| First time home buyers (output) | Increase in net worth and savings | |

| Community-led housing (output) | ||

| Access to basic banking services including credit (output) | Number of credit-challenged individuals who have participated in special programmes, including payment flexibility, non-citizens | |

| Green homes financed (output) | Progress in well-being | |

| Homes suitable for people with disabilities (output) | ||

| Repayment rate (output) | Repayment attitude and savings | |

| Average loan amount for small lending (output) | ||

| Credit score improvements (output) | Interest rate reductions for customers |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kocornik-Mina, A.; Bastida-Vialcanet, R.; Eguiguren Huerta, M. Social Impact of Value-Based Banking: Best Practises and a Continuity Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147681

Kocornik-Mina A, Bastida-Vialcanet R, Eguiguren Huerta M. Social Impact of Value-Based Banking: Best Practises and a Continuity Framework. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147681

Chicago/Turabian StyleKocornik-Mina, Adriana, Ramon Bastida-Vialcanet, and Marcos Eguiguren Huerta. 2021. "Social Impact of Value-Based Banking: Best Practises and a Continuity Framework" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147681

APA StyleKocornik-Mina, A., Bastida-Vialcanet, R., & Eguiguren Huerta, M. (2021). Social Impact of Value-Based Banking: Best Practises and a Continuity Framework. Sustainability, 13(14), 7681. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147681