Abstract

In contemporary China, the rapidly urbanized cities are exposed to a broad range of natural and human-made emergencies, such as COVID-19. Responding to emergencies successfully requires widespread participation of local government sectors that engages in diversified collaboration behaviors across organizational boundaries for achieving sustainability. However, the multi-organizational collaborative process is highly dynamic and complex, as well as its outcomes are uncertain underlying the emergency response network. Examining characteristics of the collaborative process and exploring how collaborative behaviors local governmental sectors engaging in the impact their perceived outcomes is essential to understand how disastrous situations are addressed by collaborative efforts in emergency management. This research investigates diversified collaborative behaviors in emergency response and then examines this using a multi-dimensional model consisting of joint decision making, joint implementation, compromised autonomy, resource sharing, and trust building. We surveyed 148 local governments and their affiliated sectors in China in-depth understanding how collaborative processes contribute to perceived outcomes from perspectives of participating sectors in the context of a centralized political-administrative system. A structural equation model (SEM) is employed to encode multiple dimensions of the collaborative process, perceived outcomes, as well as their relationships. The empirical finding indicates that joint decision making and implementation positively affect the perceived outcomes significantly. The empirical results indicate that joint decision making and joint implementation affect perceived outcomes significantly. Instead, resource sharing and trust building do not affect the outcomes positively as expected. Additionally, compromised autonomy negatively affects the collaborative outcomes. We also discuss the institutional advantages for achieving successful outcomes in emergency management in China by reducing the degree of compromised autonomy. Our findings provide insight that can improve efforts to build and maintain a collaborative process to respond to emergencies.

1. Introduction

In the past four decades, China is in the process of rapid urbanization and industrialization. The frequent occurrence of natural and human-made disasters has become one of the most important public problems in contemporary China, threatening the sustainable development of economic and social systems [1]. Once the emergencies break out, it often involves a large number of tasks within a limited time. Rapidly responding to disasters is the only way to reduce disastrous consequences. Emergency response in jurisdictional areas present challenges to local governments and overwhelms their capabilities in the dynamic and complex environment. Therefore, widespread collaboration across governmental sectors in jurisdictional areas of local governments is essential to achieve a successful emergency response. To improve collective actions among the responding sectors with responsibilities, expertise, resources, and information, local governments increasingly develop a broad range of collaborative mechanisms [2,3] to build and maintain a collaborative process in emergency management. In these governance arrangements, local government sectors work with others to assess the situation, and to develop and implement solutions to address emergencies. Emergency management networks are characterized by complex interactions, high dynamics, and uncertainty. The underlying collaboration across organizational boundaries is a continuous process in which numerous network actors interact with one another formally and informally through repetitive negotiation, development of plans, and execution of their commitments [4]. The collaborative process in the emergency management network is deemed to be important to achieve successful emergency management in existing literature [5,6,7]. However, the collaborative process and outcomes in emergency management networks remain elusive concepts. Studies on how emergency management networks of local governments work to achieve outcomes, in which most of the actors are public organizations and the underlying collaborative process are mandated, remain limited. The impact of different dimensions of the collaborative process on outcomes must be investigated [8,9]. To better understand collaborative governance process underlying emergency management networks, examining different dimensions of the collaborative process and their impacts on outcomes is necessary [10] to achieve successful emergency management. The existing empirical research on collaborative emergency management is mainly conducted in North American and European areas [11]. In addition, the research is dominated by case studies and small-N comparative case studies with limited efforts to explore the generalizability of the relevant hypotheses [12].

This paper explores the effects of the collaborative process on collaborative outcomes underlying the emergency management networks of local governments in China. The collaborative process and outcomes in emergency management networks of local governments in Shenzhen City in China are measure and surveyed. This research defines the collaborative outcomes from the perspective of participating organizations, explains how the collaborative outcomes are affected by different dimensions of the collaborative process, and how to achieve them by improving the process of the emergency management network of local governments. By linking the collaborative process to outcomes, this research helps to elaborate theoretical and policy insights to achieve outcomes successfully. In the following, the collaborative process and perceived outcomes are examined from the perspective of local government sectors in the field of emergency management in China. The structural equation model (SEM) is used to model and analyze the causal relationships of latent variables representing multiple dimensions of the collaborative process, such as joint decision making, joint operation, compromised autonomy, resource sharing, trust buildingand collaborative outcomes. This article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the emergency management networks on a local government level, as well as the underlying collaborative process and outcomes. Section 3 presents multiple dimensions of the collaborative process and hypotheses on how they affect the collaborative outcomes. In Section 4, measuring variables of multiple dimensions of the collaborative process and outcomes, data sources, and the SEM for verifying the proposed hypotheses are introduced. The analysis results are present in Section 5. Finally, theoretical and practical insights to improve collaborative emergency management at the local government level, and limitations of this research are discussed in Section 6.

2. Collaborative Emergency Response at a Local Government Level in China

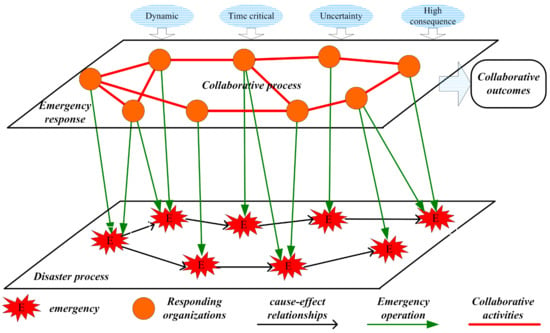

Emergency response is the most important process to minimize the negative consequences of disasters in cities for achieving sustainability and resilience. As the disaster process always involves multiple interrelated emergencies, local governments must mobilize a broad range of local governmental sectors with different expertise and resources to address such complex disaster situations effectively [13]. These government sectors take on numerous disaster mitigation operations for protecting peoples and their properties in jurisdictional areas. As shown in Figure 1, an emergency always triggers numerous cascading events in the jurisdictional areas of local governments during the disaster process. Addressing the disaster process involves responsibilities and operations of multiple sectors in a local government level. For achieving collective outcomes during emergency response, the involved sectors should collaborate with each other by sharing information, resources, and knowledge, making joint decisions and formulating joint solutions, performing tasks together, and so on. In the context of emergency response, collaborative behaviors are defined as processes that promote multiple participating organizations to arrange and solve problems that cannot be addressed by a single sector [14]. Collaboration across sectors, jurisdictions, territorial boundaries, and level of authority are essential to achieve a successful emergency response. The existing literature indicates that disaster management through inter-organizational collaboration can save administrative costs and optimize the efficiency of resources [15].

Figure 1.

The collaborative emergency response at a local government level in China.

In China, local governments assume responsibilities of managing various possible emergencies within jurisdictional areas and play important roles in the whole national emergency management system [16]. It has been recognized that most investors should be made in community disaster management capacity at a local government level for addressing emergencies effectively and successfully [17,18,19]. Local governments always establish partnerships or collaborative mechanisms with other public, private, and nonprofit sectors, or maintain informal collaboration and interaction among them to achieve successful collective outcomes [2,20].

In China, local governments set up emergency command headquarters, program emergency preparedness plans, conduct emergency drills, and reserve emergency resources to prepare for and respond to emergencies [21]. Once emergencies break out, local governments mobilize and integrate capabilities of all relevant organizations to reduce disastrous consequences in the response and recovery phase [22]. However, addressing disasters always overwhelms the capabilities of a single local government. In addition, differences in authorities, responsibilities, resources, expertise, and information among responsible sectors involved in emergency management exists. Mobilizing local government sectors to engage in emergency response, and improving collaboration and cooperation across their organizational boundaries to prepare for, respond to, and recover from emergencies are necessary. Local government networks with organizations in jurisdictional areas and other levels of government must deliver emergency services to affected people efficiently. Designing and maintaining collaborative relationships among local governments and other organizations, as well as between levels of governments, are essential to achieve successful emergency management. In China, local governments pay much more attention to form stable governance networks to improve collaboration and coordination across organizational boundaries to address disasters. Emergency management networks are recognized to be the most appropriate organizational form for solving “wicked problems” caused by natural and human-made disasters [23]. Understanding the collaborative process underlying emergency management networks from local government sectors and how it affects perceived outcomes are essential for developing collaborative mechanisms in this specific field.

3. The Collaborative Process and Outcomes during Emergency Response at a Local Government Level

The efforts of local government sectors to build and maintain a collaborative process are of importance to achieve better outcomes in the policy area of emergency management. This section introduces the context of emergency management of local governments, as well as the involved collaborative process and outcomes.

3.1. The Collaborative Process Across Organizational Boundaries Involving in Emergency Response

Collaborative process across organizational boundaries refers to the interaction among participating organizations through formal and informal negotiations, jointly creating rules and structures governing their relationships and how to act or decide on issues that brought them together. Enhancing the collaborative level among participating organizations underlying emergency management networks of local governments to address disasters is of importance. The existing literature indicates that collaboration is manifested and widespread in solution formulation [24], resource and information sharing [25], and building trust relationships [26], and so on. Ansell indicated that face-to-face communication, confidence building, process agreement building, and mutual understanding are involved in the collaboration process [7]. Thomson conceptualized and measured the collaboration process from five dimensions, namely, governance, administration, autonomy, reciprocity, and standard norms and proposed a set of indicators to measure the collaboration process. In this research, the collaborative process underlying emergency management networks of local governments are investigated and understood from the aforementioned five dimensions. Furthermore, how each type of collaborative process affects the outcomes remains unclear and must be explored to provide insights into improving emergency management of local governments. In this part, each type of inter-organizational interaction involved in preparing for, responding to, and recovering from disasters by leveraging emergency management networks for local governments is introduced and highlighted as follows:

First, the governance dimension of the collaboration highlights the inter-organizational decision making process and who is eligible to make decisions, which actions are allowed or constrained, what information must be provided, and how costs and benefits are to be distributed. In this specific field, the governance dimension of the collaborative process can be called joint decision making. Especially the formal decision making always comes from institutional arrangements and becomes one of the main factors affecting the level of cross-organizational collaboration under uncertain conditions [27]. To address disasters, local governments in China establish specific emergency command headquarters comprising representatives from relevant organizations to improve such types of collaborative process. Furthermore, local governments program emergency preparedness plans before emergencies and develop emergency response and recovery solutions once emergencies break out. Relevant departments and experts in this field must participate in joint decision making together to improve solutions.

Second, the management dimension is about the implementation process and management activities to achieve purposes and is also called joint operation. In practice, roles and responsibilities are determined and specified by emergency command headquarters to improve the collaborative process. The needs of information [28] and communication [29] are of significance important to foster participation in collective action, which can not only improving the level of the collaborative process, but also constructing a bridge among different organizations. Therefore, the information reporting and communication channels, decision making procedures, emergency response procedures, and mechanisms for monitoring each other’s activities are highlighted in China. When responding to emergencies, emergency managers from local governments, functional group representatives, or experts in relevant fields should meet at the emergency command center to analyze the situation, formulate and deploy emergency response plans for addressing the reported disaster situations.

The third dimension is organizational autonomy, which reflects the independence of the participating organizations. In efforts to collaborate, participants maintain their unique authority and objectives, while achieving common outcomes of the emergency management network. Galaskiewicz [30] explained the tension that the organization wants to maintain autonomous control, while recognizing that they must work together with other organizations to survive. Especially in addressing disasters, it often exceeds the ability of an individual sector. To perform their tasks or responsibilities, integrating the capabilities of others and to reduce their own autonomy is essential. However, in the emergency management network of local governments, the involved actors avoid collaboration when it fails to maximize their benefits which caused resources and information unable to be shared among actors, thereby affecting the collaboration and cooperation process in the network.

The fourth is the reciprocity dimension which refers to sharing resources and information. In the emergency management networks of local governments, information sharing plays important role in achieving successful emergency response to disasters [31]. Given the differing capabilities of actors, one should obtain resources from others to perform their own tasks and achieve common objectives. The information and resource sharing in the emergency management of local governments is mainly manifested in the following aspects. First, standard procedures of information collection and reporting are formalized. According to the classification and summary of the disaster situation, emergency management departments will share information with the members of the special emergency command headquarters, the street offices, and all the resident units. Third, response systems of sharing emergency materials, experts, emergency technologies, and equipment are highlighted to realize objectives in the emergency management of local governments. Different organizations have distinct professional resources, knowledge, and information, which are essential for emergency managers to make decisions through communication across organizations.

The fifth dimension is trust and respect, and trust can strengthen the degree of mutual collaboration. Vangen and Huxham [32] discussed that collaboration should be conducted by building trust. Isabella [33] put forward that communication, trust, and experience are essential in the collaborative process. However, in the Chinese emergency management system, there is an unclear division of responsibilities, which leads to the lack of trust among sectors. Therefore, local governments train emergency managers and conduct emergency drills to increase trust among organizations.

3.2. Outcomes in Emergency Management Networks of Local Government

Given that the collaboration processes becomes widespread in emergency management of local governments, how to achieve successful outcomes of disaster response is the main objective and remains without a clear answer [33]. For exploring which factors in the collaborative process realize good outcomes in the emergency management networks of local governments, the notion of outcomes of the networks must be understood and conceptualized. Much discussion on outcomes of governance networks exists in current literature. However, measuring the outcomes of emergency management networks is difficult because the governance process involves many actors and is uncertain in the context of emergency management.

The outcomes of the collaborative process during emergency response have multiple dimensions [34]. In the time dimension, the effects of multi-organizational networks can be divided into short, medium, and long terms [35]. The short-term effect refers to the direct result of collaboration, including increasing social capital, creating new knowledge, reaching high-quality collaboration agreement, and developing innovative strategy; the medium-term effect occurs during collaboration or outside the formal border of collaboration, including the establishment of new partnerships, construction of new infrastructure, coordination of joint action, improvement of mutual learning ability, implementation of the collaboration agreements, and updating the concept of collaboration. Finally, the long-term effect includes reducing social conflicts, strengthening services, resources, urban and regional adaptability, generating new institutions, solving public problems, and establishing new standards and new discourse models.

Furthermore, the outcomes of emergency management can be measured in the level of participating organizations, whole network, and stakeholders out of the network. The collaborative process should satisfy each participating organization, while outputting collective outcomes to achieve common objectives. In addition, the evaluating outcomes of the collaborative process underlying networks should consider the opinions of governments in upper levels, people in the jurisdictional areas, and so on.

In the field of emergency management, local governments should understand and consider outcomes of the collaborative process underlying the multiple organizational networks. Despite the multiple dimensions of the outcomes, this article mainly explains the collaborative outcomes from three aspects and believes that inter-organizational collaboration can achieve the overall goals for better. By strengthening the interaction between organizations and increasing the experience of collaborative learning, it provides the foundation for inter-organizational collaboration in emergency situations. The details of measuring collaborative outcomes are present in Section 4.

4. Hypotheses of the Effects of the Collaborative Process on Outcomes in Emergency Response

According to the collaborative process and outcomes underlying emergency management networks of local governments to address various disasters, this section attempts to explore how the collaborative process impacts the network outcomes. The basic research question is that whether the collaborative process produces better outcomes of emergency management. A set of theoretical hypotheses on how each dimension of the collaborative process impacts the outcomes are presented in the context of local government emergency management.

4.1. Joint Decision Making and Collaborative Outcomes

Joint decision making in emergency management refers to the involved actors engaged in setting objectives and developing solutions to deal with disastrous situations before or during emergencies. The decision making process involves information, authority, and knowledge of multiple organizations in jurisdictional areas of local governments. Participating in the decision making forum to formulate incident objectives and develop plans improve partners’ satisfaction and common solutions [36,37]. More actors that participate in the joint decision making process means that more information is collected to assess the emergency situation, thereby improving the quality of the solutions to address disasters. Thus, joint decision making in the collaboration process is assumed to affect outcomes and effectiveness of the collaboration process. According to the analysis, the following hypothesis is listed as follows.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Joint decision making process underlying emergency management networks positively affect the collaboration outcomes.

4.2. Joint Operations and Collaborative Outcomes

Joint operations refer to the process of performing specific tasks or providing services to people affected by disasters. Participants in emergency management networks of local governments lack collaborative experiences and do not understand one another very well. Given the wide range of consequences of emergencies and numerous participants, achieving effective collective actions are difficult. Thus, the joint operation process involved in addressing emergencies, specified roles and responsibilities, emergency response procedures, emergency command, and monitoring mechanisms is essential to coordinate the behaviors of network actors [38]. The roles and responsibilities of participants can be stipulated before emergencies, and the involved tasks can be identified. Once emergencies occur, the joint operations underlying the emergency management networks can be strengthened, which is important to promote the effectiveness of emergency response [39]. Therefore, this study made the following assumption.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

The better the joint implementation, the better the collaboration outcomes.

4.3. Compromised Autonomy and Collaborative Outcomes

When engaging in boundary-spanning activities with others during emergency management, organizations inevitably face maintaining individual autonomy and achieving collective objectives. The reality creates the tension between maintaining their authorities and identity to achieve individual organizational objectives and maintaining accountability to others to achieve collective objectives. Compromised autonomy indicates that an organization can clearly identify its own values and organizational authority from collaborative behaviors [40]. In emergency management work, organizations must submit independence to collaborate with others, which is the cost of achieving collective objectives of collaborative behaviors. Kettl and Donald [41] believe that the key reason for forming cross-organizational collaboration is that the public managers and policymakers realized government cannot rely on unilateral power to solve public problems. From the analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

The greater degree an organization compromises its autonomy, the worse collective outcomes will be output by the collaborative process in the emergency management networks.

4.4. Resource Sharing and Collaborative Outcomes

Resource independence is the most important factor in establishing collaborative relationships [42]. In the emergency management network, resources, information, and capabilities are diversified for each organization. For performing their responsibilities, organizations not only use their own resources and capabilities, but also need resources and information of others [43,44]. Sharing resources embodied in the whole process of responding to disasters, organizations can leverage their own resources and capabilities to help others and share information to achieve common gains and win-win situations, thereby strengthening the abilities to address disasters through collaboration across organizational boundaries. As a type of collaborative behavior, resource sharing should be identified and improved to achieve individual and collective outcomes. The fourth hypothesis on resource sharing is proposed as follows.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

The higher the level of resource sharing, the better collaborative outcomes will be perceived in the emergency management of local governments.

4.5. Trust Building and Collaboration Outcomes

Trust relationships between actors are deemed to be the foundational mechanism to foster collaborative behaviors [27]. If a trust lacks among government departments, inter-organizational collaboration cannot be realized when responding to unexpected emergencies. As an informal relationship, trust across organizational boundaries is formed in the interactive process underlying the emergency management network. It plays an important role in improving the collaborative level. The existing literature indicates that trust among members of the organization can form a good sense of mutual understanding, which can help coordinate behaviors among organizations and promote the confidence of members, which reduces transaction costs [6,45]. Trust between organizations is the key factor in ensuring the smooth operation underlying the organization’s networks. Therefore, trust significantly and positively affects collaborative outcomes. In emergency management practice, emergency drills are conducted to foster trust among organizations for improving the degree of inter-organizational collaboration. According to the analysis, the following hypothesis is listed as follows:

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

The higher degree of trust building among organizations, the better collaborative outcomes will be perceived in the emergency management of local governments.

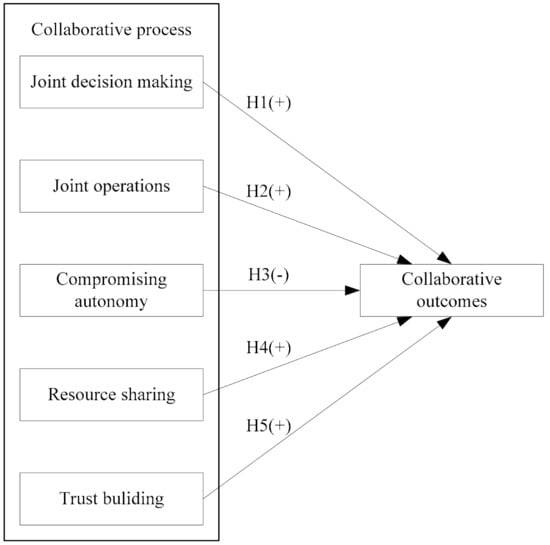

The aforementioned five hypotheses refer to five types of collaborative behaviors involving emergency management of local governments. Figure 2 presents the conceptual model of theorized relationships between each dimension of the collaborative process and outcomes underlying emergency management networks of local governments. Local governments must understand the five dimensions of the collaborative process and manage them intentionally to address emergencies successfully to achieve better outcomes. Thus, understanding and analyzing the impact of different dimensions of the collaborative process and collaborative outcomes present a theoretical framework for examining the interactive behaviors across organizational boundaries in local government emergency management and conducting empirical research on how to achieve better outcomes by improving the collaborative process.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of theorized relationships between each dimension of the collaborative process and outcomes.

5. Measuring Variables, Data Sources, and Research Method

This section describes how to measure the involved variables in the following empirical research. In addition, the data source and research method of structure equation are also introduced.

5.1. Measuring Variables

According to the proposed theoretical hypotheses in the previous section, the involved variables include joint decision making, joint operation, compromised autonomy, resource sharing, trust building, and collaborative outcomes. In this empirical research, these variables are latent and are difficult to be quantified. According to the literature, the measuring method of these variables is proposed.

Measuring Each Dimension of the Collaborative Process

In local government emergency management, collaboration refers to an interactive process among organizations that involves negotiation, formulation, and assessment solutions, and implementation of commitments. The collaborative process is ambiguous, dynamic, and complex in nature. The proposed five theoretical hypotheses involve measuring different dimensions of the collaboration process. In this section, each dimension of the collaborative process is conceptualized and measured according to the existing literature, and is adjusted for adapting to the characteristics of local government emergency management.

In addressing disasters, the joint decision making is mainly reflected in developing solutions to disastrous situations, such as preparedness emergency plans before emergencies and emergency response plans after the emergencies break out. In this research, asking the opinions of participants about negotiation and developing policies and solutions to address disasters to achieve common objectives is necessary. The joint decision making was measured as an index of two survey questions, which asks about the level of agreement with the statement: (1) The partner organization will consider options or suggestions of your organization seriously when making decisions on addressing disasters. (2) Your organization works with other partner organizations to develop solutions together in emergency management. Joint decision making is designed as a latent factor underlying the aforementioned variables.

Joint operation refers to performing the developed plans through an effective operating system, in which the clarity of role and responsibilities, recognition of common objectives, and establishment of effective communication channels are essential. Four indicators called observed factors are designed to measure the latent variable of joint operation. They are four survey questions, namely, (1) as a representative of your organization, you understand the roles and responsibilities of your organization in emergency management. (2) Partner organizations play an important role in addressing disasters. (3) Partner organizations agree about the collective objectives of emergency management. (4) In addressing disasters, partner organizations coordinate well with your organization.

In the emergency management network of local government, each actor negotiates, develop, and implements their commitments based on their individual and collective interests. The dimension of compromised autonomy captures the extent of shared interest and interdependence among partners. In the context of emergency management of local governments, a contradiction exists between self- and collective-interests. Managers from each organization should try to reduce their interest loss, while understanding that they will achieve higher efficiency when collaborating with others. The interests of network actors are different; they compromise with one another in addressing disasters to achieve effective collaboration. In this research, three survey questions are used to measure these latent variables, namely, (1) the collaboration hinders your organization from achieving its own mission or concerns. (2) Your organization’s independence has been affected or reduced by working with partner organizations in emergency management. (3) As a representative of your organization, you feel pulled between trying to achieve your organization’s expectations and the collective objective of collaboration.

Resource sharing is essential in the collaborative process underlying the emergency management network of local governments. The resources include not only material resources, but also information. For measuring the resource-sharing level in the collaborative process underlying the emergency management network, five survey questions are designed, namely, (1) partner organizations use one another’s resources, and all partners benefit from the collaboration process. (2) Your organization share information with partner organizations, which enhances their plans and improves their operations. (3) Your organization’s work in emergency management is appreciated and respected by partner organizations through collaboration. (4) Your organization achieves your own objectives better by work with partner organizations than working alone in emergency management. (5) Despite the differences among partner organizations in addressing emergencies, win-win solutions can be achieved through collaboration across organizational boundaries.

In the process of collaboration, trust is a prerequisite for any form of collaborative behaviors across organizational boundaries. Collaboration is also conceptualized as a trust building process. The trust provides common beliefs among multiple partners. One organization performs its own work well and may be willing to bear the disproportional cost because they think that their partners will equalize the distribution of the benefits and costs. In this research, trust building is measured by three indicators, such as (1) in addressing disasters, representatives of engaging organizations are trustworthy. (2) My organization can count on partner organizations to fulfill their obligations to address disasters. (3) My organization believes that working with partner organizations in emergency management and leaving the collaborative process is worthwhile.

The aforementioned five dimensions of the collaborative process are regarded as latent variables, and 17 indices are proposed to measure them in the field of emergency management. To explore the relationships between the collaborative process and outcomes in this specific field, the collaborative outcomes cannot be observed and should also be conceptualized and measured. Ostrom [46] regarded autonomy as a positive result of collective action, that is, only through creditable commitment, supervision, and support from other departments can the organization solve the problem successfully. Huxham [41] believes that collaboration has instrumental results and ideological consequences by interaction across organizational boundaries. The members in the emergency management networks of local governments can better realize their objectives involved in addressing disasters through collaboration. Meanwhile, a collaboration involving the process of preparedness, response, and recovery phase in emergency management can facilitate close communication and interaction among organizations, impacting the emergency management work in the future. Finally, the accumulation of experience in emergency management paved the way for subsequent inter-organizational collaboration, which is also an outcome of the collaborative process. From the analysis of the latent variables of collaborative outcomes, three indicators are proposed to measure collaborative outcomes. The first indicator of collaborative outcomes refers to the degree of achieving individual objectives of participating organizations. When collaborating with other organizations, each organization should achieve common objectives of the whole emergency management network, as well as their own objectives. Therefore, specifying each organization’s responsibilities, understanding the types of objectives to reduce autonomy to a certain degree, and assume relevant losses are necessary. Achieving the individual objectives in the emergency management of local governments motivates organizations to participate in this work in the future. The second indicator of collaborative outcomes is about the degree of strengthening interaction among organizations. Interactions include inter-organizational linkages and exchanges, which reflect the sharing of resources and information and reciprocity [47]. By enhancing interaction among organizations, local governments can ensure timely, efficient, and comprehensive emergency management to address emergencies successfully. The third indicator of collaborative outcomes refers to increasing the collaborative learning experience. Continuous learning shows the characteristics of successful collaboration among organizations [48], and learning by collaborating with others is especially important for organizations in the uncertain and dynamic environment as emergency management [49]. In other words, continuous learning is the most effective way and means to recognize objectives, learn what to do and what cannot be done. Similarly, increasing the collaboration experience can also positively influence the level of trust among organizations, which is essential for managing emergencies successfully. Therefore, the past collaborative learning experience is crucial for mobilizing and integrating government, enterprises, and non-governmental organizations to provide emergency services to affected people. For measuring all the latent variables involved in H1 to H5, 20 specific observed variables are proposed, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptions of measurement variables of the collaborative process and outcomes.

5.2. Data Sources

This research collected data from Shenzhen City, which is a highly urbanized coastal area in southeast China. There exist 11 administration districts in this city. Various major disasters, such as the landslide in Guangming New Area on 20 December 2015, and the Shanzhu Typhoon, which hit Guangdong on 16 September 2018, caused serious consequences. The Shenzhen district-level local governments pay attention to the formation and maintenance of emergency management networks at their level to prepare for and respond to possible disasters. In this research, the questionnaire was designed according to Table 1. A total of 148 emergency managers from the main responsible sectors in the 11emergency management networks of district government level in Shenzhen City were surveyed. In this research, organizations and their interactions across boundaries in the emergency management networks are the objects of study in this research. Thus, all the interviewees are surveyed representing their organizations. The authors try to interview managers at higher levels in their sectors and are familiar with emergency management business. The survey data was collected from July 2016 to February 2017. A total of 148 managers in different organizations with emergency management responsibilities were interviewed and filled in the questionnaires. To avoid invalid data, face-to-face interviews, and questionnaire surveys were adopted.

The questionnaire covers items for measuring each observed variable in Table 1. For measuring the latent variables representing joint decision making, joint operation, compromised autonomy, resource sharing, trust building, and collaborative outcomes, 20 items are listed in questionnaires. The responders are required to evaluate each item according to the Likert-type scale to express the extent of recognition. The Likert scale ranges from 1 representing “strongly disagree” to 7 representing “strongly agree.” In addition, to learn more about respondents, the administrative rank, time of employment, and time of performing emergency management were also surveyed.

5.3. Research Method

The proposed hypotheses involve multiple latent and observed variables, as well as their relationships. SEM [50] is a suitable research method to test all the hypotheses. It is preferred over regression analysis because of its capacity to estimate observed and latent variables. In this research, multiple latent variables that cannot be measured directly are involved, such as multiple dimensions of the collaborative process and outcomes. Thus, it needs to be measured by other observed variables.

Furthermore, SEM software Amos 17.0 is performed to explore how each dimension of the collaborative process impacts the collaborative outcomes in this research. This tool can not only express the independent relationship among variables in the model, but can also consider their mutual influence.

6. Analysis and Results

6.1. Descriptive Statistics Analysis

Descriptive statistics of all the survey items are presented in Table 2. The results show that most of the responders to be surveyed are at the department director level. This indicates that most of the responders are well acquainted with collaborative activities across organizational boundaries. The working time of performing emergency management ranging from 1 to 5 years for responders is 61.5%. This indicates that the responders are familiar with emergency management business in their sectors, and the survey information reflects the actual collaborative process and outcomes in emergency management of local governments. The mean values of observed variables measuring joint decision making, joint operation, resource sharing, and trust building are more than five, while the mean values of those measuring compromised autonomy are about two. This indicates that the level of collaborative process is high in this empirical research. Finally, the collaborative outcomes are high according to the mean values of the relevant observed variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the observed variables.

6.2. SEM Results

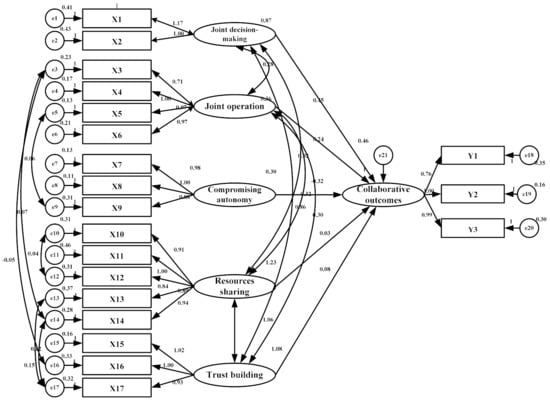

There exist 148 responses in our dataset reflecting the 148 participating organizations and their interaction across organizational boundaries. The SEM reflects the latent variables representing joint decision making, joint operation, compromised autonomy, resources sharing, trust building, and collaborative outcomes, as well as their path coefficients. Through twice modification, the SEM achieved a good model fit (RMSEA = 0.076, χ2 = 282.23, df = 152, χ2/df = 1.857, NFI = 0.893, CFI = 0.947, IFI = 0.948). These indicators satisfy the general cut-off points for the structure model and indicates that it is compatible with the reached data.

Figure 3 presents the final SEM results. As shown, each dimension of the collaborative process underlying the emergency management network of local governments impacts the outcomes directly with different degrees. As shown, the direct impacts from joint decision making and joint operation are significant, whereas those from resource sharing and trust building are minimal. The compromised autonomy dimension of the collaborative process negatively affects the collaborative outcomes. Meanwhile, each type of interaction involved in the collaborative process achieves the collaborative outcomes in different paths. It reflects complex mechanisms achieving collaborative outcomes through collaboration underlying the emergency management network of local governments in China.

Figure 3.

Structure model results of how each dimension of the collaborative process impacts the outcomes.

Meanwhile, these results indicate that each dimension of the collaborative process interacts with one another. Table 3 presents the covariances matrix of the five dimensions of the collaborative process, which reflects the covariant relationship among these latent variables. The covariant relation value of joint decision making and resource sharing or trust building is relatively high, which is close to 1 in the range of 0.86–0.92. It indicates that the factor of joint decision making significantly influences resources sharing and trust building. On the contrary, the trust building dimension is also reacted with the resources sharing, indicating that strengthening the trust building between organizations plays a key role in improving resource sharing and joint decision making, and improving resource sharing can be achieved through joint decision making.

Table 3.

Covariances matrix of five dimensions of the collaborative process.

6.3. Testing Hypotheses

According to the SEM results, the total impacts from each dimension of the collaborative process to outcomes in the context of emergency management in China are calculated and are presented in Table 4. The regression coefficient is normalized and shown to facilitate comparison.

Table 4.

Total impacts from each dimension of the collaborative process to outcomes.

H1 assumes a positive relationship between joint decision making in emergency management and collaborative outcomes. Our analysis results support H1. As shown in Table 4, the total path coefficient from this dimension of the collaborative process to collaborative outcomes is 0.453. The significant and positive effect indicates that joint decision making impact collaborating outcomes to the greatest degree. This finding indicates that in emergency management of local governments, improving joint decision making is the most effective method for good collaborative outcomes. Thereby, to achieve successful emergency management, local governments should encourage involved organizations and stakeholders to participate in the decision making process, and consider advice and opinions from the responsible organizations seriously during the decision making process.

H2 focuses on effects from the joint operation during the emergency management to the collaborative outcomes. As shown, this hypothesis is verified and posits that the higher level of joint operation, the better collaborative outcomes will be achieved. The total normalized path coefficient from joint operation dimension to collaborative outcomes is 0.244. It means that the joint operation across organizational boundaries improves collaborative outcomes significantly.

H3 assumes the negative impacts from compromised autonomy to collaborative outcomes. H3 shows that the relationships between compromised autonomy and collaborative outcomes are verified, and the detailed path coefficient is −0.321. H4 and H5 are also verified in this empirical research. As shown in Table 4, the total path coefficient from resource sharing and trust building to collaborative outcomes is low. These results indicate that policy instruments for improving resource sharing and trust building do not play the important roles as expected. This provides insights into emergency management practices.

According to the large-N empirical research, the joint decision making, joint operation, compromised autonomy, resource sharing, and trust building behaviors involved in the collaborative process impact the collaborative outcome differently. The results provide theoretical and practical insights to achieve successful collaborative governance in emergency management.

7. Discussions

This research examines how each dimension of the collaborative process underlying the emergency management network affects the outcomes in the context of local governments in China. The conceptual framework in Figure 1 represents all the proposed hypotheses that capture the essence of how the collaborative process affect the outcomes. However, the collaborative process is complex and has multiple dimensions, impacting the collaborative outcomes from the organizational view must be explored. Our research supports all the proposed hypotheses, but several findings provide insights to improve the local government emergency management from collaboration perspectives.

First, the joint decision making underlying the emergency management network affects the collaborative to the highest degree. The path coefficient is 0.405. That is to say, to improve the collaborative outcomes, establishing a joint decision making forum and fostering multi-organizational decision making environment are the most effective methods. In China, special command headquarters comprising representatives from the involved organizations are founded to assess emergency situations and develop solutions to address disasters. From this empirical research, it improves the collaborative outcomes effectively. Involved organizations should be mobilized to participate in the forums of the special command headquarters, and provide information, situation assessment, and suggestions to improve the degree of joint decision making. In emergency management, the authority of local governments is deemed to be the essential factor in achieving better collaborative outcomes. Instead, the widespread participation of organizations with emergency management responsibilities is the most important factor in achieving better outcomes. Therefore, local governments in China should mobilize more organizations in jurisdictional areas to participate in emergency management work, enhance communication and interaction in situation assessment, solutions development, and so on.

Second, this empirical research finding indicates that the joint operation dimension of the collaborative process is another important factor that positively affects collaborative outcomes. Therefore, the roles and responsibilities of each organization involved in the emergency management of local governments should be specified. Especially, most of the organizations involved in the emergency management of local governments are public sectors. Fulfilling the responsibilities is the main motivation of participating in emergency management work. Furthermore, identifying and understanding common objectives of emergency management play an important role in emergency management. The meeting mechanisms are also important in this specific field to improve collaborative outcomes.

Third, compromised autonomy will reduce collaborative outcomes significantly. The collaborative process is defined from the collective action view that focuses on the emergency management network of interdependent of semiautonomous organizations. All organizations engaging in boundary-spanning activities in the emergency management work of local governments should balance their individual interest and collective concerns. Giving up the controlling over their activities can improve the collaborative outcomes. In the administrative culture of local governments in China, the collective interests are highlighted to be higher than each organizational interest. In addition, the organizational system of the Communist Party of China in jurisdictional areas of local government plays an important role in managing conflicts among the participating organizations to achieve successful emergency management in contemporary China. These are the institutional advantages of China, which should be emphasized in this specific field.

Finally, resource sharing and trust building during the collaborative process cannot improve the collaborative outcomes significantly. The path coefficient from resource sharing to collaborative outcomes is 0.03, and that from trust building to collaborative outcomes is 0.079. By interviewing emergency managers in local governments in China, the organizations are responsible for addressing emergencies in a specific industry, and emergency resources are purchased and managed independently. The low level of resource sharing reduces the efficiency of emergency resources, which should be paid attention to in the future. Trust is deemed as the main mechanism to achieve collaboration in multiple organizational networks in the existing literature [51]. However, the emergency management networks of local governments are characterized by mandated interaction and much uncertainty. Most network actors are public sectors. In this specific field, the methods of enhancing trust level among participating organizations do not lead better collaborative outcomes significantly. Hierarchical and horizontal governance mechanisms take into effect to achieve successful emergency management. Trust relationships among involved organizations are the auxiliary mechanisms to improve collaborative outcomes. This provides insight into designing strategies in local government emergency management.

8. Conclusions

Local governments respond faster to disasters and activate inter-organizational network approaches to manage diversified emergencies in jurisdictional areas by employing numerous policy instruments. The collaborative process underlying networks of addressing disasters leads to successful emergency management. In the emergency management network of local governments, the underlying collaborative process is mandated, and most of the network actors are public organizations. In this research, how each dimension of the collaborative process, such as joint decision making, joint implementation, compromised autonomy, resource sharing, and trust building, impact the collaborative outcomes is examined in the context of the emergency management network of local governments in China. The empirical findings indicate that joint decision making and joint implementation positively affect the collaborative outcomes significantly. The resource sharing and trust building do not positively affect the collaborative outcomes significantly. In addition, compromised autonomy will negatively affect the collaborative outcomes. These findings provide insights into designing emergency management policies to improve collaborative outcomes. In addition, the institutional advantages for improving collaborative outcomes in emergency management by reducing the degree of compromised autonomy are discussed. Understanding the collaborative process underlying emergency management networks on a local government level from different dimensions and examining the relationships between them and collaborative outcomes provide new insights to achieve successful emergency management. The future work will focus on how the partner characteristics, institutional arrangement, and network management abilities improve collaborative outcomes by affecting the collaborative process in the emergency management network.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, analysis, visualization, writing (original draft preparation): P.T. and S.S.; writing (review and editing): P.T., S.S. and D.Z.; supervision, project administration: P.T. and H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Science Fund of China (Project Nos. 71774068 and 71303093), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (Project No. 21612301), the Major Project of National Social Sciences Fund (Project No. 18ZDA308), the Social Science Fund of the Ministry of Education of China (Project No. 18YJC63026).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank servants from government sectors from Shenzhen City, Guangdong province, China for completing the questionnaire survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander, D. A magnitude scale for cascading disasters. Int. J. Disast. Risk. Reduct. 2018, 30, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C. The Institutional Collective Action Framework. Policy. Stud. J. 2013, 41, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Ma, L. Coordination structures and mechanisms for crisis management in China: Challenges of complexity. Public Organ. Rev. 2020, 20, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomson, A.M.; Perry, J.L. Collaboration processes: Inside the black box. Public Admin. Rev. 2006, 66, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.M.; Perry, J.L.; Miller, T.K. Conceptualizing and measuring collaboration. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2009, 19, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, B. Antecedents or processes? Determinants of perceived effectiveness of interorganizational collaborations for public service delivery. Int. Public. Manag. J. 2010, 13, 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tierney, K. Disaster governance: Social, political, and economic dimensions. Annu. Rev. Env. Resour. 2012, 37, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, B.; Steelman, T.; Velez, A.K.; Yang, Z. The structure of effective governance of disaster response networks: Insights from the field. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2018, 48, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulibarri, N. Collaboration in federal hydropower licensing: Impacts on process, outputs, and outcomes. Public Perform. Manag. 2015, 38, 578–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nohrstedt, D.; Bynander, F.; Parker, C.; Hart, P. Managing crises collaboratively: Prospects and problems—A systematic literature review. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2018, 1, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parker, C.F.; Nohrstedt, D.; Baird, J.; Hermansson, H.; Rubin, O.; Baekkeskov, E. Collaborative crisis management: A plausibility probe of core assumptions. Policy Soc. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynander, F.; Nohrstedt, D. Collaborative Crisis Management: Inter-Organizational Approaches to Extreme Events. Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, L.B.; O′Leary, R. Conclusion: Parallel play, not collaboration: Missing questions, missing connections. Public Admin. Rev. 2006, 66, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, C.J.; Lynn, L.E., Jr. Governance and Performance: New Perspectives; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, A.O.; Parsons, B.M. Making connections: Performance regimes and extreme events. Public Admin. Rev. 2013, 73, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgin, F.P. A History of Federal Disaster Relief Legislation, 1950–1974; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, R.S. The History and Politics of Disaster Management in the United States; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1990; pp. 101–130. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, L.A.; Li, X.; Remer, K. Local government structure: Maybe it doesn’t really matter? Cities 2020, 96, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, L.; Na, L. Network Governance: Theory and Practice for Local Governments in China; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Henstra, D. Evaluating local government emergency management programs: What framework should public managers adopt? Public Admin. Rev. 2010, 70, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylves, R.T.; Waugh, W.L. Disaster Management in the US and Canada: The Politics, Policymaking, Administration, and Analysis of Emergency Management; Charles, C.T., Ed.; Publisher: Springfield, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cristofoli, D.; Macciò, L.; Pedrazzi, L. Structure, mechanisms, and managers in successful networks. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschmann, M.A.; Kuhn, T.R.; Pfarrer, M.D. A communicative framework of value in cross-sector partnerships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 332–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, M.; Perrot, F.; Rivera-Santos, M. New perspectives on learning and innovation in cross-sector collaborations. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1700–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Robertson, P.J.; Lewis, L.; Sloane, D.; Galloway-Gilliam, L.; Nomachi, J. Trust in a cross-sectoral interorganizational network: An empirical investigation of antecedents. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2012, 41, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara, K.U.; Katarzyna, S.M.Y. Inter-Organisational Coordination for Sustainable Local Governance: Public Safety Management in Poland. Sustainability 2016, 8, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Huggins, T.J.; Prasanna, R. Information Technologies Supporting Emergency Management Controllers in New Zealand. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Orozco, B.; Rosell, J.; Merçon, J.; Bueno, I.; Alatorre-Frenk, G.; Langle-Flores, A.; Lobato, A. Challenges and Strategies in Place-Based Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration for Sustainability: Learning from Experiences in the Global South. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galaskiewicz, J. Interorganizational relations. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1985, 11, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenhu, Y. NGOs’ Mobilization in Foreign Major Disaster Emergency and its Revelation. XUE HUI 2010, 12, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Vangen, S.; Huxham, C. Nurturing collaborative relations: Building trust in interorganizational collaboration. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2003, 39, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nolte, I.M.; Boenigk, S. Public–nonprofit partnership performance in a disaster context: The case of Haiti. Public Admin. 2011, 89, 1385–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N. Performance under stress: Managing emergencies and disasters: Introduction. Public Perform. Manag. 2009, 32, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Consensus building and complex adaptive systems: A framework for evaluating collaborative planning. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 1999, 65, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, S.K.; White, M.A. Learning and knowledge transfer in strategic alliances: A social exchange view. Organ. Stud. 2005, 26, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, M. Managing networks: Propositions on what managers do and why they do it. Public Admin. Rev. 2002, 62, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Thibault, L. Challenges in multiple cross-sector partnerships. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2009, 38, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Boin, A.; Keller, A. Managing transboundary crises: Identifying the building blocks of an effective response system. J. Conting. Crisis. Man. 2010, 18, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxham, C. Creating Collaborative Advantage; Sage: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kettl, D.F. The job of government: Interweaving public functions and private hands. Public Admin. Rev. 2015, 75, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A.; Vaidyanath, D. Alliance management as a source of competitive advantage. J. Manag. 2002, 28, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirag, I.; Khadaroo, I.; Stapleton, P.; Stevenson, C. The diffusion of risks in public private partnership contracts. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssen, G.; Perrini, F.; Tencati, A.; Lacy, P.; Holmes, S.; Moir, L. Developing a conceptual framework to identify corporate innovations through engagement with non-profit stakeholders. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, Z.; Difang, W.; Ming, J. The Research on the Relationship between the Trust and the Collaboration Effects under the Background of PPP—the Accommodation Function of Environment Uncertainty and the Partner′s Behavior Uncertainty. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2008, 29, 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Benington, J.; Moore, M.H. Public Value: Theory and Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, W.D.; Weible, C.M.; Vince, S.R.; Siddiki, S.N.; Calanni, J.C. Fostering learning through collaboration: Knowledge acquisition and belief change in marine aquaculture partnerships. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2014, 24, 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, K.S.; Feldman, M.S. Boundaries as junctures: Collaborative boundary work for building efficient resilience. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2014, 24, 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn, E.; Edelenbos, J.; Steijn, B. Trust in governance networks: Its impacts on outcomes. Admin. Soc. 2010, 42, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).