1. Introduction

A special historical feature of Central and Eastern Europe is that, during the formation of national borders, many areas with ethnically diverse populations came under the jurisdiction of other nation states as regions inhabited by minority nationalities. The European Union has inherited many of these historically cohesive cultural and ethnic areas in the course of its eastern enlargement. For a long time, the aim of national borders was to separate national territories from one another, but due to the European Union’s integrative approach, the number of examples of cross-border cooperation is steadily growing [

1].

One of the main driving forces of the European Union is to turn the dividing borders into connecting borders by strengthening the cohesion between states and regions, thus, encouraging regions to remedy the existing ethnic and cultural fragmentation by increasing the intensity and number of cross-border contacts. Through these, the EU intends to enhance cross-border integration, which is necessary for enhanced integration at the European level. Cross-border development of tourist destinations can play a significant role in this process.

Nationally oriented tourism in cross-border areas has shifted to an approach that attempts to link ethnic and cultural heritage on both sides of the borders in an attempt to increase their attractiveness [

2]. At the same time, an increasing amount of EU funded INTERREG programmes have incorporated tourism and especially cultural projects within the framework of cross-border programmes.

“There is a great societal value of research on cross-border tourism as this is an indicative process of European integration” [

3,

4,

5]. Research on the subject focuses mainly on tourism policy, tourism development in cross-border projects and on the potential of tourism in regional development [

1,

4,

5,

6]. However, cultural tourism in cross-border regions with similar cultural groups has yet to be explored in detail.

This contribution focuses on the border region between Slovakia and Hungary, specifically on the cross-border region of Komárom and Komárno. The evaluation concentrates on four aspects: the nature of cultural tourism in the area, resident, and visitor perceptions of the cultural tourism offering, opportunities to increase cross-border collaboration, and options to improve the cultural tourism offerings of the area. The findings are based on the empirical results of a standardized questionnaire carried out in Komárom and Komárno.

Our theoretical hypothesis is that the search for identity amongst the residents in cross-border regions generates an increasing demand for cultural tourism, as visiting the sites of national cultural heritage, participation in pilgrimages, etc. are significant motivating factors when traveling to the other side of the border. There are numerous examples of this phenomenon, e.g., the trips of Hungarians to Transylvania (Romania), of Bulgarians to the current North-Macedonia, and of Romanians to Bulgaria [

7,

8] and Moldova [

9,

10].

This led to the creation of a specific tourism product and niche market, both for the sending and receiving countries, whereas the terminology in tourism literature cannot adequately describe this phenomenon at all. In the case of Bulgaria, the tourist arrivals from the neighbouring countries take about 50% of the total number of international arrivals. The Romanian tourists have the biggest share in the arrivals from the neighbouring countries—an average 30%, while the Republic of Macedonia has about 10%. The Romanians regularly visit (among other destinations) the border cities, such as Ruse, Vidin, and other cities; cultural and historic places in the Northern part of Bulgaria. [

11,

12].

In relation to our theoretical hypothesis, our research focuses on proving that, in symbolic places, such as the cross-border area of Komárom and Komárno, the cultural values, monuments, and heritage sites are the strongest attraction factors for nationality-based cultural tourism. The cities have other cultural and non-cultural attractions (spas, Danube ports, and Roman heritage); however, in the minds of visitors and locals, the elements of the national cultural heritage are in focus.

Since 1999, the border section between Slovakia and Hungary has been continuously involved in cross-border cooperation programmes supported by the EU. One of the first grants to support the development of cross-border cooperation was the Visegrad Fund. The theme of cultural heritage has gradually become increasingly important in the Hungarian–Slovak programmes and now accounts for more than 1/3 of the projects, while the protection and valorisation of the natural and cultural heritage account for about 2/3 of the total programme budget (

Table 1).

However, if we look beyond these statistics, there are only a few cultural projects, and there are not any traces of cultural integration in the border area. With one or two exceptions, it is difficult to detect any kind of cooperation between the management of cultural heritage sites renovated previously with the support of cooperation programmes. Within the framework of the Hungary–Slovakia Cross-border Co-operation Programme 2007–2013 (HUSK), there were only three projects with a focus on fostering integrated tourism development in the cross-border region of Komárom–Komárno: the cleaning, reconstruction, and joint promotion of the Fortress, the promotion of folk music and folk dance in Hungary and Slovakia, and the creation of joint destination management organisations, which can transport tourists on both sides of the border.

Within the framework of the INTERREG V-A Slovakia–Hungary Cooperation Programme 2014–2020, we can only find two cultural projects focusing on the examined cross-border region: the CULTPLAY project with an aim to involve local people and visitors in the regions to use their existing cultural heritage in a new way (through playgrounds representing historic sites of the region) and the FEBO project, which is a joint action for the utilization of the common natural and cultural heritage in the SK-HU border regions. There are no traces of continuation of the projects implemented during the previous programming period, and, with the exception of some joint cultural programmes related to the Fortress, there is not any effort to jointly promote or manage them.

Based on the differentiation by Timothy [

17] on the spatial relationship between destinations on both sides of a border, Komárom and Komárno are favourable destinations for cross-border tourism development. Visitors are interested in visiting both sides of the border, despite that the cultural attractions are not operating as one entity. There are other associations contributing to cross-border cooperation, e.g., the Vág-Duna-Ipoly/Váh-Dunaj-Ipel Regional Association (VDIR) with the aim of making the region more attractive through coordinated development in several areas.

Based on Martinez [

18] cross-border partnership in tourism can be described as collaboration, which means that there are joint efforts to work together on development issues; however, interactions between stakeholders are not in the phase of full integration. Apparently, the borders, which are losing their importance within the EU, are still having an impact in this respect: cross-border cultural and heritage tourism destinations have not been integrated.

2. Aspects of Cultural Tourism

In a first approach, Bernecker [

19] attempted to group the types and forms of tourism. In doing so, he used the determining factors, i.e., motivation and environment, as grouping criteria. Therefore, according to motivation, we can talk about recreational tourism (relaxation and holidays for physical regeneration), social tourism (visiting relatives and club tourism), sports tourism (active and passive sports tourism), economic tourism (business tourism, business tourism, congress tourism, exhibition), political tourism (diplomatic and conference tourism as well as tourism related to political events), and cultural tourism (to learn about other cultures, customs, traditions, and religions).

In the 1960–1970s, with the growth of discretionary income and consumption and with the appearance of mass international tourism in Europe, culture became an increasingly important element of tourism, which, in turn, led to the development of a cultural tourism niche market. By the early 1990s, cultural tourism accounted for about 37% of mass international tourism [

20]. According to Robinson and Smith [

21], the period after the 1990s also opened up new spaces for cultural tourism. The continuous development of cultural tourism centres and the spread of low-cost airlines across Europe played a key role in stimulating tourism, which, in turn, led to ‘smaller’ cultural destinations, such as Bratislava, Riga, Budapest, Krakow, and Ljubljana, becoming major tourism destinations.

Programs, such as the European Capital of Culture and the growing supply of festivals and cultural events, led to the emergence of a competitive landscape for cultural tourism. The 1990s—referred to as the cultural tourism boom era—also opened up the mass market for cultural tourism, and it became a dominant phenomenon in many tourist destinations.

This led to a growing interest among researchers [

22] and consequently to many definitional and conceptual challenges surrounding the meaning of ‘culture’, ’cultural region’, or ’cultural tourism’ as scientific disciplines, e.g., geography or sociology applied different interpretations of them. Initially the term ‘cultural tourism’ was used interchangeably with heritage tourism. One of the best known definitions of cultural tourism was formulated by Richards [

23].

According to his conceptual definition, “cultural tourism is the movement of persons to cultural attractions away from their normal place of residence, with the intention to gather new information and experiences to satisfy their cultural needs” [

23,

24]. Richards also specified cultural tourism as “any movement of persons to cultural attractions, such as heritage sites, artistic and cultural manifestations and arts away from their normal place of residence” (p. 24).

According to Silberberg [

24] (p. 361), cultural tourism can be defined as “...a visit by people outside the host community motivated in whole or in part by an interest in the historical, artistic, scientific or lifestyle/heritage offerings of a community or region...” [

24] (p. 361). Tighe [

25] examined the three main elements of cultural tourism, travel, tourists, and sites, and came to the conclusion that cultural tourism is directed towards exploring historical sites, museums, and arts. Tighe also described the cultural tourist as a tourist “who visits historic sites, monuments and buildings, museums and galleries; attends concerts and performing arts; and is interested in learning about the culture of the destination” [

25] (p. 387).

In 1983, UNWTO provided an official definition, which states that cultural tourism includes the movement of persons for cultural motives, such as travel to festivals and other cultural events and to cultural sites and monuments as well as travel to study nature, folklore, or art [

26]. This was redefined in 2017 at the UNWTO General Assembly in Chengdu and is currently understood as “a type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience and consume the tangible and intangible cultural attractions/products in a tourism destination. These attractions/products relate to a set of distinctive material, intellectual, spiritual and emotional features of a society that encompasses arts and architecture, historical and cultural heritage, culinary heritage, literature, music, creative industries and the living cultures with their lifestyles, value systems, beliefs and traditions” [

27].

As mentioned, the research on cultural tourism has led to several definitions; furthermore, the terms cultural and heritage tourism have been used synonymously. The two concepts are closely related, and both are considered to be the most widespread segments of tourism and among the oldest forms of travel, and as such we consider the examination of heritage tourism important as well. In the next chapter we focus on definitions of heritage tourism and on the common elements between cultural and heritage tourism.

2.1. Heritage Tourism

According to historical sources, the ancient Egyptians and Romans as well as the medieval nobility travelled to culturally significant historical places [

28]. Hall and Zeppel [

29] observed experientialism as a common element between cultural tourism and heritage tourism, and noted that, in the context of heritage tourism, it is narrowed down to cultural heritage and “is connected with visiting selected landscapes, historical places, buildings and landmarks—here the experience occurs via searching for contact with nature and sense of unity with the history of the visited site” [

29] (p. 87). The issue of heritage is still unclear; however, researchers on the subject agree on the point that heritage is, in fact, the present use of the past [

30]. However, this definition of heritage does not focus directly on tourism use, and Boyd and Bulter [

31], Thorsell and Sigaty [

32], and even UNESCO have attempted to extend the scope of definition to include natural heritage as well.

It is in this context that Timothy and Boyd developed their own definition of heritage tourism: “This form of travel entails visits to sites of historical importance, including built environments and urban areas, ancient monuments and dwellings, rural and agricultural landscapes, locations where historic events occurred and places where interesting and significant cultures stand out” [

33] (p. 2).

It is also clear from these definitions that much of the research on heritage tourism focuses on the supply side, a view confirmed by Leask and Fyall [

34], who argued that research focuses mainly on the interpretation, conservation, and other elements of resource management as well as the services provided for visitors of historic places. In contrast, on the demand side, there is a growing need to focus on the motivational factors of heritage tourists. During their research on heritage demand, Herbert et al. [

35] found that, in most cases, visitors to heritage sites are better educated, travel in groups, have a higher than average income, and spend more.

In the context of heritage tourism, it is important to note that heritage is a complex phenomenon with a highly political nature; therefore, it is one of the most controversial types of tourism due to its historical dimensions [

36]. In some cases, deliberate efforts can be observed not only to ignore parts of the past but also to erase it altogether. Light [

37] cites, as an example of this, the situation in Romania and Hungary in the 1990s, when post-communist governments attempted to erase the remnants of the communist past. These actions were prevented by interest groups, who argued that the history of this era should be preserved too.

Heritage tourism is commonly used to create a sense of patriotism in the residents of a nation state and to spread propaganda to international visitors. Heritage sites are often presented in a way that highlights the virtues of a particular political ideology, e.g., in socialist countries, tours usually include visits to monuments dedicated to great communist leaders and patriots. This is also a feature of the area we are studying. These kinds of tours also include visits to schools, community centres, factories, and specially designed villages where residents (often actors) lead idealised communist lifestyles. Heritage sites and events are often used as a means of reinforcing nationalism and patriotism among domestic tourists: battlefields, cemeteries, monuments of national heroes, and other important sites in the national psyche are central elements for this particular use of heritage.

Another example of the complexity and highly political nature of heritage is social/collective amnesia, which refers to the selective memory of certain events and people, or the deliberate disregard of certain historical events. There are numerous examples of this in some parts of South-East Asia and in relation to the Chinese, Native American, and African-American people. There are groups of people, who, at one point in history, were oppressed by the dominant ethnic group, which resulted in their past being erased or rewritten [

38]. The discussion of ethnicity in the tourism is not only of interest in the context of history and, thus, heritage tourism but is also linked to culture and, thus, to cultural tourism. As it is linked to cultural tourism, the next chapter will look at ethnic tourism.

2.2. Ethnic Tourism

The analysis of social interactions between tourists and locals often involves the study of inter-ethnic relations. Tourism brings together people, who are often members of different ethnic groups. Domestic tourism, in most cases, does not necessarily involve interactions with other cultures; however, in the case of international tourism, contact with other cultures is of great importance [

39]. In addition, ethnic tourism accounts for a significant part of global tourism, and can best be described as ‘the search for the authentic cultural experience’ [

40].

Van der Berghe’s [

40] definition of ethnic tourism is almost synonymous with that of Smith [

41], who defined it as visiting exotic and often peripheral destinations, which involve performances, representations, and attractions portraying or presented by ethnic groups. Smith’s work has been the starting point for the anthropological research on tourism; however, its anthropological nature has also led to many debates. Smith used the terms ‘host’ and ‘guest’, which have since been debated by many scholars due to their limits when referring to the encounters between tourists and people living in the visited destinations.

Selwyn (1994) critiqued the terms due to their limited analytical value for a complex industry involving many relationships [

39]. MacCannell [

42], on the other hand, argued that the global spread of white culture and the accompanying tourism institutions create highly deterministic ethnic forms. MacCannell drew attention to the use of ethnicity in tourism as exotic cultures become tourist attractions, while distinguishing the ethnic approach to tourism from earlier ethnological and colonial perspectives. MacCannell also stated that tourist ethnicity is dependent on earlier forms of constructed ethnicity, and is, thus, rooted in earlier formulations of identity. He also argued that the use of reconstructed ethnicity in tourism is an attempt to universalize the Western sense of exchange.

Several researchers expressed concern about how tourism presents ethnicity to consumers; however, relatively little attention is paid to actions and motivations: too much emphasis is placed on Western values in the context of global tourism [

39]. Wood refines Smith’s [

41] definition and points to “the cultural uniqueness that is marketed for tourists” [

43]. According to Wood, the focus is on cultural practices and “the observation of indigenous homes and villages, dances and rituals” [

43] (p. 361). ‘Otherness’ and ‘other’ ways of living are re-dimensioned as a commodity to be consumed as tourists are exposed to cultural differences.

This leads to differentiation and to the resurgence of culture and ethnicity. However, a distinction between ethnic and cultural tourism can be discerned, as the former is used to refer to ‘primitive cultures’ and the latter to the high arts of developed nations [

44]. “Currently, Western scholars use the term ‘ethnic tourism’ when cultural differences are great and ‘cultural tourism’ when they are less so” [

44] (p. 91). In relation to that distinction, the next chapter focuses on the motivations and background of cultural and heritage tourism related to ethnicity.

2.3. Motivations and Background of Cultural and Heritage Tourism Related to Ethnicity

MacCannell claimed that ethnicity in tourism is dependent on earlier forms of constructed ethnicity, and thus it is rooted in the earlier constructions of identity. It can, thus, be seen that tourism often creates “staged” or inauthentic authenticity to meet the expectations of the visitor. This idea is supported by Lanfant [

45], who argued that the reconstruction of identity begins with the ‘gaze of the stranger’ acting as a point of reference and a guarantor of identity. Tourist perceptions are shaped by the complex and often competing voices of authority.

The interactions between the tourists and hosts are usually temporary, mostly one-off, bilateral, of limited duration, and for specific or instrumental purposes. As tourist–host interactions are carried out across a wide range of linguistic and cultural barriers, they are vulnerable to misinterpretation and may be subject to stereotyping [

46].

While exploring the background of ethnic tourism, border maintenance is an important concept when studying the impact of tourism on indigenous cultures. Picard [

47] argued that the emphasis is on the ability of local people to maintain a dichotomy of meanings and that cultural identity will continue to be of significant importance to local people regardless of the presence of tourists. This allows the integrity of the societies in question to be examined and demonstrates that tourism reinforces the boundary between what people do for visitors and what they do for themselves.

The use of the term ‘ethnicity’ varies widely in political discourse, the first main theoretical distinction is made between the so-called ‘ancestral’ and ‘situational’ or ‘instrumental’ approaches [

48]. According to the ancestral viewpoint, ethnic identity comes from being born into a particular community, identifying with the values of that community, speaking its language or even a dialect of its language, and following a set of cultural practices. Ethnicity is not closely related or linked to class or political phenomena, and ethnicity, therefore, has its own internal dynamism, existing independently from other elements of the political phenomenon [

48].

The instrumentalist perspective takes a more dynamic view and treats ethnicity as a set of social relations. Barth [

49] raised the question of where the boundaries between different groups may lie, and refused to see ethnicity as the property of cultural groups, thus, avoiding any notion of cultural determinism [

50]. Along these lines, several authors, such as Eidheim [

51], have developed concepts for the analysis of interpersonal ethnicity. The essence of this approach is that it conceives of ethnicity as a social process in which cultural differences are communicated, facilitating comparison without resorting to simplistic formulations of cultural groups.

The situational approach rejects the simplistic notion of culture as bounded entities and focuses on ethnicity as a set of social relations and processes through which cultural differences can be communicated [

52]. Ethnicity appears to be more stable than other markers of individual and group identity. Barth observed multi-ethnic societies constituted under the control of a state system dominated by one of the ethnic groups [

49]. Similar observations were made by Smith [

53], who used Malinowski’s institutional theory (1944) to analyse the meaning of cultural differentiation.

Looking at the Caribbean, Smith argued that there was no single society but rather several societies side by side, each with its own set of institutions. Ethnic identities tend to be associated with different languages, although this may prove problematic if identities are reassessed in the context of tourism [

53]. An example of this was given by Esman [

54] regarding the situation of Cajuns, who are mixed descendants of Nova Scotian exiles whose culture combines Native American, French, Spanish, and German elements and who speak dialects of French. Sometimes an ethnicity is so closely associated with a particular activity that the name is applied to all persons engaged in such an activity.

An example of this is the term Sherpa, which actually refers to the occupation of mountaineering and trekking in Nepal [

55]. According to MacCannell, tourism promotes the restoration of ethnic characteristics and, therefore, resembles the behaviour of leaders of separatist ethnic groups [

42]. Pitchford, however, argued that this is a two-way process and that ethno-nationalist rhetoric can ‘bear a striking resemblance to the image created by the promotion of tourism’ [

56] (p. 48) citing Welsh culture as an example of this, where the ‘victim image’ created for tourism purposes fits in well with nationalist attitudes.

Ethnicity can be used as a ‘rhetorical weapon’ as well in tourism to draw attention to alleged grievances [

42] (p. 168). The ethnicity of modern Hungary, for example, includes the core elements of the former Kingdom of Hungary. A large part of its territory was annexed to neighbouring countries after the 1920 Trianon peace treaty, which resulted in around 2.5 million Hungarians living today in the neighbouring countries, especially in Transylvania, where loyalty to Hungarian identity creates the illusion of the continuation of a former political reality [

57].

Examples of this include Dunajská Streda or Komárno, where Hungarians in Southern Slovakia preserve their Hungarian identity. Hungary is also an excellent example of ethnic sentimentalism in ethnic tourism. A wide range of the motivations described above apply in our case study area, complemented by the most prominent motivating factor: the search for identity. There is a significant demand for tourism from Hungarians who are interested in their own past and the traditions of their people or the homeland of their ancestors, who emigrated. In the following chapter, we introduce our case study area with special regard to the constructed conflicting ethnic picture of Komárno.

3. Introduction to the Case Study Area

3.1. Presentation of the Study Region

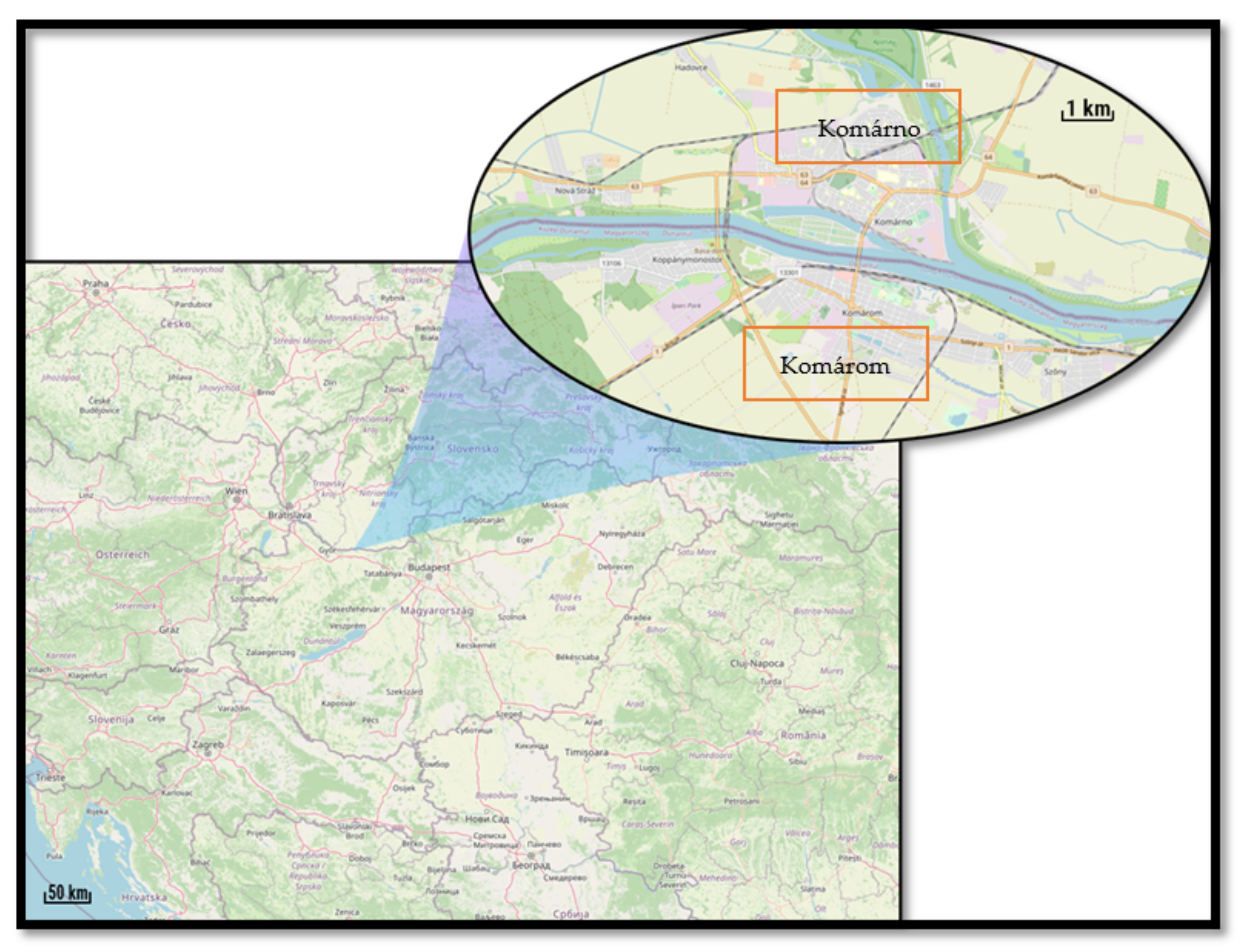

Our case study area is the cross-border twin city of Komárom–Komárno lying on each side of the Danube between Slovakia and Hungary, respectively (

Figure 1).

Komárom, as one the main cities of Komárom–Esztergom County, has a population of almost 19,000 persons who live in an area of 70 square kilometres [

58]. The number of inhabitants in Komárno is almost twice as large as the number of inhabitants in Komárom [

58]. In 2019, Komárom–Esztergom County was Hungary’s fourth most advanced area after the main capital, Győr-Moson-Sopron County, and Fejér County by GDP per capita [

58]. The region of Nitra is the third most advanced area in Slovakia [

59].

In 2011, Komárno (Slovakia) had 34,349 inhabitants, and 53.9% declared themselves as Hungarians and 33.5% as Slovaks), while Komárom was home to 19,284 (Hungarian) people. At the same time, the Hungarian town is one of the most developed industrial centres of the country: more than 16,000 persons are employed by the companies settled down in its industrial park opened in 1998.

On the contrary, the shipyard in Komárno was the largest company of the two towns before the system transformation in 1990 when more than 4000 workers went bankrupt (its reanimation is under progress now), and, in 2003, the unemployment rate in the town reached 22%. Thanks to the EU accession and the opening of the border, almost 5000 Slovakian workers found new jobs on the Hungarian side after 2004. They mostly arrived from a distance of 50 kms, where the Hungarian minority represents a majority in Slovakia (nearly two thirds of the population of the Komárno district are Hungarians) [

60].

The cross-border twin city attracts a high number of visitors. Based on estimates by Komárom TDM, tourists spend an average of 90,000 tourist nights there. The city pair is officially classified as two separate destinations; however, the two sides offer a number of parallel and complementary tourism elements, and there is considerable movement between them. This is officially considered “international” tourism, but it takes place in the same local space. Citizens of Komárom and Komárno frequently use the other side’s facilities (cinemas, theatres, spas, museums, etc.), which can officially be called “international” tourism as well, while, in reality, they simply walk across the cross-border Komárom–Komárno bridge.

The majority of the population on the Slovakian side is of Hungarian nationality as are the majority of the people living in the area. Thus, visitors can be divided into two specific categories: those who come from the two cities’ respective states and who, while they visit the other side of the same cultural heritage, become “international” one-day excursionists or tourists (if they spend one or more night(s) on the other side of the border); and those local residents, who become “international” excursionists when they use the services on the other side of the river.

For each of these groups, a distinction can be made between Hungarian nationalities (whether they come from Hungary or from other parts of Slovakia), who come primarily to visit the historical and national heritage, and between Slovak nationalities, who are motivated by the common past or historical values and by other activities, such as wellness, sports, and other attractions that do not fall into the category of cultural tourism. These segments also overlap. The number of classic international tourists coming from other countries is still low.

Local and regional tourism institutions are well established in the area. Tourism destination management organisations operate in both cities; however, their activities are mainly separate. An EGTC association has been set up on a cross-border basis, which, among its many tasks in the tourism sector, has projects on both sides (e.g., the CULTPLAY project, the joint bicycle route, and the operation of the cross-border bicycle rental service: Komárom Bike). At the same time, the main attractions under state management (the two sides of the Fortification System and museums) are being developed separately [

61]. Their joint development would be useful because together these assets would be “visible” on an international level (e.g., the fortification system and the Danube’s river/fluvial navigation). However, joint comprehensive planning has not yet started.

3.2. The History of the Komárom–Komárno City Pair

The area has a rich archaeological and historical heritage as it was inhabited from the oldest ages and formed important parts of the Limes defending the Roman Empire from the barbarian troops. Classifying the Danubian cities, Hardi [

62] differentiated between typical city pairs developed in parallel on both banks of the river and bridge-towns in which the urban centre was located on one side and gradually stretched over the Danube (a third group is characterized by nautical functions). The history of Komárom–Komárno began as a bridge-town and developed to a city pair by the end of the 20th century.

The historical town of Komárom was located exclusively on the northern side of the Danube, and acted as an important river crossing point of the Hungarian Kingdom. At the beginning of the 18th century, due to its prominent geographical location (meeting point between the east and the west, halfway between Vienna and Buda, where also the products of the mountainous north and the grainfields of the south were exchanged) Komárom became the fifth largest town of the kingdom [

63]. In the 19th century, its significance remarkably declined after three larger earthquakes and the modernisation of water transport along the Danube.

The new renaissance of the town began when, in 1892, the Elisabeth Bridge connected it with the municipality of Új-Szőny lying on the southern bank of the river. This resulted in the unification of the two municipalities in 1896 under the name Komárom. As a result, the population of the town increased by one quarter, and Komárom obtained access to the Budapest–Vienna railway (launched in 1856), which was physically connected with the town in 1909 by a railway bridge over the Danube [

63,

64,

65]. Due to its gradually enlarged fortification system stretching over the Danube, Komárom became one of the most important military centres of the Austro–Hungarian Monarchy whose economy included the most advanced industrial sectors.

The Peace Treaty of Trianon in 1920 dissolved the Austro–Hungarian Monarchy and the newly established state of Czechoslovakia was rewarded with the former Northern territories of Hungary, present-day Slovakia. The Danube became a state border between the newly established Czechoslovakia and Hungary, and the town of Komárom became separated. The southern part, named as Komárom, stayed part of Hungary, and the northern part, by its new name Komárno, became part of Slovakia. As an effect of the nation-building politics of the new country, Komárno was deprived from its urban status and lost its economic hinterland, separated with a strictly guarded border.

Due to the Treaty, the once united town started to develop in two divergent directions: Komárom has been systematically developed, while Komárno, as a cultural centre of the “unreliable” Hungarian minority [

66], regressed [

64]. The population of the city changed drastically: the Hungarian speaking elite mostly left Komárno and Czech, and Slovak civil servants and military personnel took their place. In 1939, following the Vienna Arbitration of 1938 Czechoslovakia gave back nearly 12 thousand km

2 and more than 1 million inhabitants (84% of them were Hungarian) to Hungary. At that time, the northern bank of the town was also returned to Hungary and two municipalities were united again under the name Komárom; however, the differences between the two societies were already observable.

After the Second World War, Komárom was divided again between Hungary and Czechoslovakia. During the communist era, the differences grew further, regardless of the fact that the ethnic composition of Komárno kept its status from the 1920s (a two thirds majority for Hungarians) [

66]. When Slovakia and Czechia separated in 1993, the Slovakian Hungarians saw that the timing was favourable for the construction of their autonomy within the new state that had been denied by the Czechoslovak governments. Komárno became the symbol of these aspirations.

On 8 January 1994, the Congress of Komárno (Komáromi Nagygyűlés) adopted the document titled ‘On the conventional status of the Hungarians’ including the different forms of autonomy and causing a fierce opposition from the Slovak side. In April 1995, the Hungarian teachers protested in the town against the planned educational reforms limiting the rights of the Hungarians. In October 1996, a large protest was held there against the cultural offenses made by the nationalist Mečiar government [

67].

Regardless of the attempts made since the system transformation (the signature of the twinning agreement in 1993, the joint events, like the Komárom Days, the common application for a World heritage status of the fortification system and the set-up of the Pons Danubii European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation, etc.) the integration of the (once united) two towns is advancing very slowly, which can be witnessed also in the weaknesses of tourism integration. One of the reasons for this failure might be the contested multi-ethnic status of Komárno, which we will describe in the next chapter.

3.3. The Constructed Conflicting Ethnic Picture of Komárno

Undisputedly, Komárno is the spiritual/cultural capital of the Hungarians living in Slovakia. With its rich historic heritage, it defines the cultural identity of the Hungarians everywhere in the world. The Old and New Fortresses resisted the largest armies of the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg troops in 1849 during the Hungarian independence war. The legendary colonel György Klapka became a symbol of the Hungarian freedom.

The town gave birth to one of the greatest Hungarian writers, Mór Jókai; the globally known composer, Ferenc Lehár; and Hans/János Selye, the chemist and endocrinologist, one of the creators of stress theory. Jókai’s name has been guarded by a secondary school and the Hungarian speaking theatre (since 1952), while Selye’s name by the Hungarian speaking university (since 2004) that is home to nearly 2000 students attending three faculties in the town [

59,

62,

67].

According to several scholars, this symbolic status of Komárno is “constructed and instrumentalised” [

68] (p. 96) by the representatives of the two nationalisms, where the symbolic places represent the “dominance of one group over the others” [

66], creating so the “illusion of absolute power” [

66] (p. 197). As Lecours [

69] stated: “In building and shaping identities, nationalist movements emphasize and politicize cultural distinctiveness; consequently, they tend to define the ‘national interest’ primarily in terms of cultural protection/preservation.”

In reality, as was mentioned before, the once united Komárom has developed into two parallel societies each with their own special identity. Due to the historical Danube navigation route, there are other minorities, e.g., Serbians (in the 17th and 18th century approximately 8000 Orthodox Serbs lived there) in the town. Mannová [

66] highlighted that many people in Komárno feel themselves somewhere in-between. This might be the reason why more than 10% of the inhabitants declared themselves as unidentified by ethnicity in 2011 [

70]. This means that “Komárno Hungarians have redefined their geographical and linguistic territory so as to symbolically belong neither exactly to Slovakia, nor exactly to Hungary…” [

68].

Simon [

64] identified this phenomenon as a distinct spirit that is more democratic and more open-minded than that of Magyars living in Hungary. As a consequence, regardless of the shared history, language, and culture, the visitors crossing the border represent today two different identities, which justifies the application of the ‘gaze of the stranger’ and the analysis of cultural tourism in the area.

4. Evaluation of Cross-Border Cultural Tourism in the Case Study Area

4.1. Methodology

To examine cross-border cultural tourism in the area, we conducted research within the framework of the EU-funded SPOT project, which aims to develop a new approach to understanding and addressing cultural tourism. Due to the specificity of the Komárom–Komárno case study area, we carried out surveys separately with the help of stakeholders to reach the residents of Komárom and Komárno and the tourists visiting the area. The surveys were standardized questionnaires provided by the team responsible for data collection in the consortium.

The target population of the residential survey was all persons aged 15 years and older living in Komárom or in Komárno. The target population for the tourist survey was defined as international and domestic visitors who entered the case study area, regardless of their gender and age. The SPOT consortium made the conscious decision on a minimum number of 40 questionnaires per category of interviewees on the basis of the comprehensive, in-depth nature of the questionnaires.

To address the residents of Komárom and Komárno, a hybrid offline–online surveying method was used. Field surveys were conducted at highly frequented places of Komárom and Komarno, e.g., at public transport entry points. Surveys were carried out at popular tourist places until the target number was reached. On the Hungarian side of the border, the surveys were conducted approaching visitors at one of our main stakeholders: the Fort Monostor, at the Brigetio Spa, and at accommodation/catering establishments.

Offline surveys were conducted approaching visitors at the Slovakian side of the fortification system and at popular cultural and historical tourist destinations in Komárno. To reach more citizens, the team used social media sites (in particular Facebook) additionally. The online questionnaire was built with LimeSurvey and was circulated in relevant groups on Facebook consisting of the citizens of Komárom. As we received only two answers through the online questionnaire from citizens of Komárom, this had no significant influence on the composition of the respondents.

The residential survey consisted of 20 questions. The set of questions was divided into eight demographic questions, 10 Likert-type ranking scales, and two open-ended questions in which respondents could provide their thoughts on specific topics. The tourist survey consisted of 29 questions. The set of questions was divided similarly into eight general questions, six closed choice questions, five open choice questions, five Likert-type ranking scales, and five open-ended questions.

Information from the closed-ended questions was measured by a 5-point Likert scale, where a score of 1 represented a not important/very low/negative impact and a score of 5 represented a very important/very high/positive impact. Closed questions were used for the quantification of opinions. While processing the data, we counted per 5-point statement the number of times that 5-4-3-2-1 was scored, and we calculated the mean value as well. Open-ended questions allowed us to collect qualitative data, e.g., about the perceived importance of cultural sites. We utilized Excel for the basic analysis of the data. In the analysis of our results, we highlight the survey findings that were relevant to the subject of this article, while focusing on basic data.

Due to the travel restrictions introduced by the two countries as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, reaching residents and tourists proved to be difficult, and carrying out the surveys took a longer time than expected. Under the coordination of Institute of Economic and Regional Studies, the surveyors on the Hungarian side of the city were university students studying sociology. Questionnaires on the Slovakian side of the city were completed with the help of the civic association Marthos (Esterházy Academy), an organization specializing in cross-border institutional cooperation. The residential and tourist surveys took place in September of 2020.

On the Hungarian side, surveyors conducted the field work in one month, and our Slovakian partner finished the research in six weeks. The team reached altogether 103 residents and 99 tourists. We reached 51 residents on the Hungarian side and 52 residents on the Slovakian side of the city. Out of the 99 respondents, 49 tourists were visiting Komárom, and 50 were interviewed in Komárno. For the tourist survey, most of the respondents were domestic visitors or tourists from the other side of the city border. On average, a third of the residents approached answered the questions, and around half of the tourists responded to the interviewers.

The number of Hungarian tourists in Komárno is very significant (Source: Komárom TDM); however, during the survey period there were not any Hungarian visitors in the city due to the restrictions during the pandemic. Komárom is an important site destination for the Slovak ethnic Hungarians tourists, but their numbers also decreased during the period. However, during the survey, tourists had to answer some of the questions for both sides of the area (this is indicated during the evaluation of the results). Since there is not any statistical data available on the general composition and demographic characteristics of the standard population of interest (cross-border tourists), the survey could not adhere to the criterion of representativeness.

4.2. Main Characteristics of the Respondents

The total number of residents surveyed was 103, of which 49.51% lived in Komárom. More than half of the respondents were female, which reflects the majority of females in the population. The share of female population in Komárom is 52%, and, in Komarno, it is 52.2% [

58,

59]. More than 2/3 of the respondents were between the ages of 20 and 50 years old, which can be attributed to the method of questioning. Elderly people are likely underrepresented in the sample because, during the period of the surveys, elderly people were advised by the government to avoid highly frequented places.

The successfully addressed respondents were usually residents commuting from/to work and running errands in the city, which explains the high percentage of people between 20 and 50 years old. Out of 103 residents, only one indicated that she was born in another country. One respondent in Slovakia answered that her country of birth was Hungary. The respondents in Komárom were all born in Hungary. In Komárno, all the other interviewees reported Slovakia as their country of birth. Around two-thirds of the respondents had more than 12 years of education, which means that either they were in the process of obtaining a university degree or had at least a bachelor’s degree.

More than 20% of the respondent were professionals, and almost 25% of them worked as clerical support workers. Managers were also highly represented in the sample, as 13% of the interviewees worked in this occupation. In comparison, based on the data of the last National Census in Komárom, 17.8% of the employed population worked as a manager, 27% had other intellectual occupations, and 15% worked as service and sales workers. We found that 31.5% of them worked in the industrial sector [

58]. In the Nitra region, most of the economically active population works in the secondary sector (75%), and 22% of them work in the tertiary sector [

59].

Most of the residents (40%) estimated their total gross household income between 11 and 20 thousand €. Most of these respondents worked as professionals, as clerical support workers, or as service/sales workers. A significant number, almost a third of the respondents, reported a household income less than 10,000 €. This is 50% higher than the average gross household income in Hungary, which was around 6700 € in 2019 [

58] and around 28% higher than the household income in Slovakia (in 2019: 7757 €, Source: CEIC). Three-person households accounted for more than a third of respondents (36%). Small average household sizes—fewer than three persons per households—made up 25% of the sample.

Out of the 99 tourist surveys delivered, 52.5% of the tourists were women. Taking into consideration that the survey was conducted over a period of time when mostly domestic tourists visited the case study area, the distribution of females and males was similar to the ratio of men and women in our case study countries. A total of 57% of the tourists were between the ages 20 and 40 years old. Their older counterparts were heavily underrepresented as the main attraction sites in the area are more frequently visited by older tourists. Out of the 99 respondents, 92 were born in the case study countries.

Analysing the data collected in Hungary and in Slovakia separately showed that the tourists interviewed in Hungary were all born in the country. Out of the tourists visiting Komarno, three had Hungary as the country of birth, one had the Czech Republic, and one had Romania as his country of birth. We found that 95% of the respondents had more than 12 years of education, which means that either they were in the process of obtaining a university degree or had at least a bachelor’s degree. Tourists with a university degree or a higher level of education made up almost half of the sample.

Almost a third of the respondents were professionals, which are occupations requiring skills at the fourth ISCO skill level. Based on the total gross household income per year, 31% of the respondents earned between 11,000 and 20,000 €, and 31% of them earned between 20,000 and 40,000 €, which is consistent with the data presented in the data analysis of residential surveys. Most of the respondents had an average household income of at least twice the average gross household income in the case study countries. This supports the claim that tourists with a higher level of education and higher income are more likely to visit the cultural attractions of a given area.

4.3. Cultural Tourism and Residents

In chapter three, we came to the conclusion that regardless of the shared history, language, and culture, the visitors crossing the border today represent two different identities. Despite that, the cultural differences are not great, and the residents of Komárom and Komárno based on Timothy’s [

17] classification are similar cultural groups. In this context, the use of the term “cultural tourism” is justified. In this chapter, first we look at the residents’ perception of cultural tourism in the area. Based on the previously discussed concepts by Wood [

43], Eidheim [

51], Eriksen [

52] and MacCannell [

42], our aim was to examine what residents think are the core elements of their identity and what is “the cultural uniqueness that is marketed for tourists” [

43].

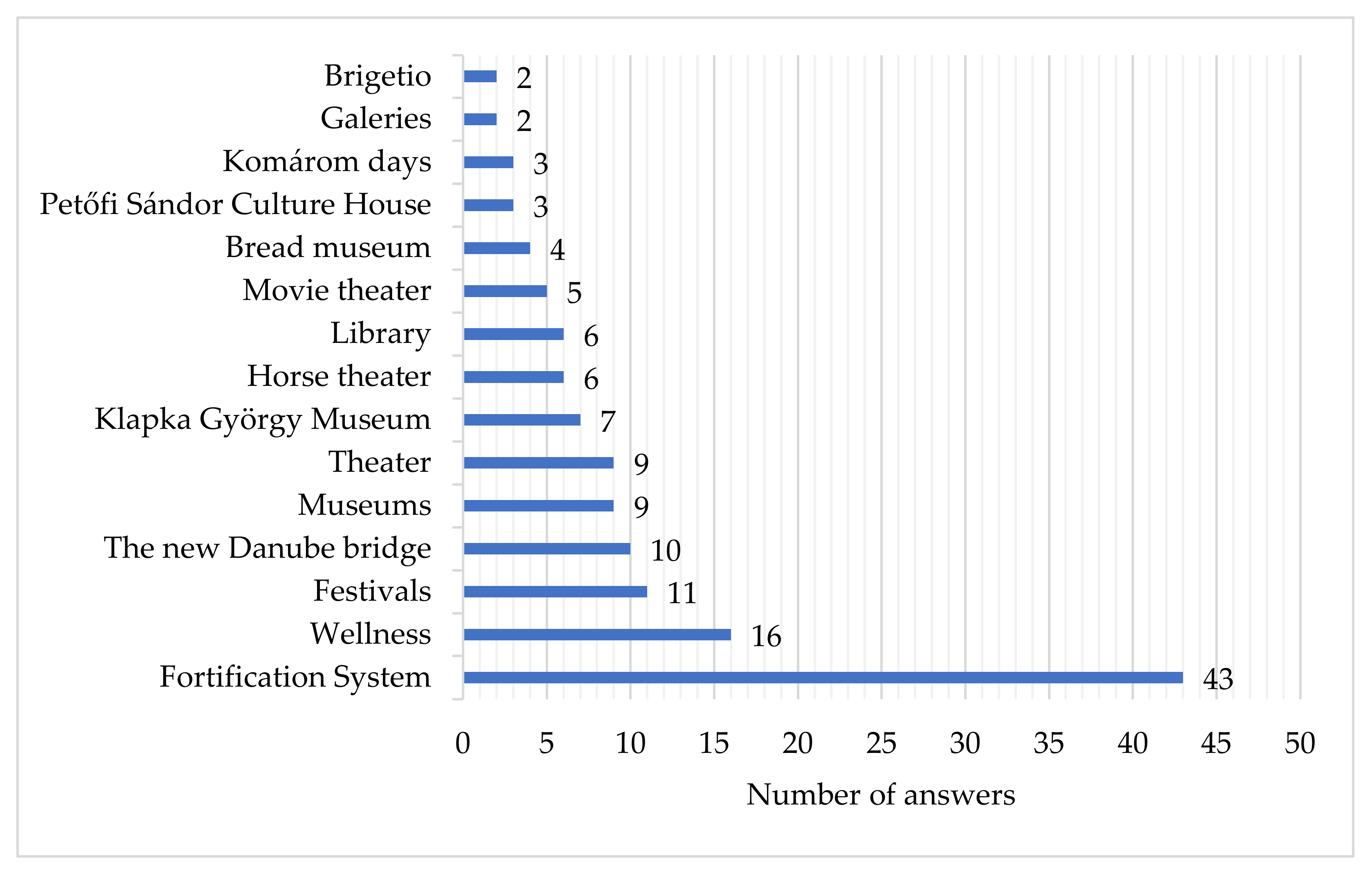

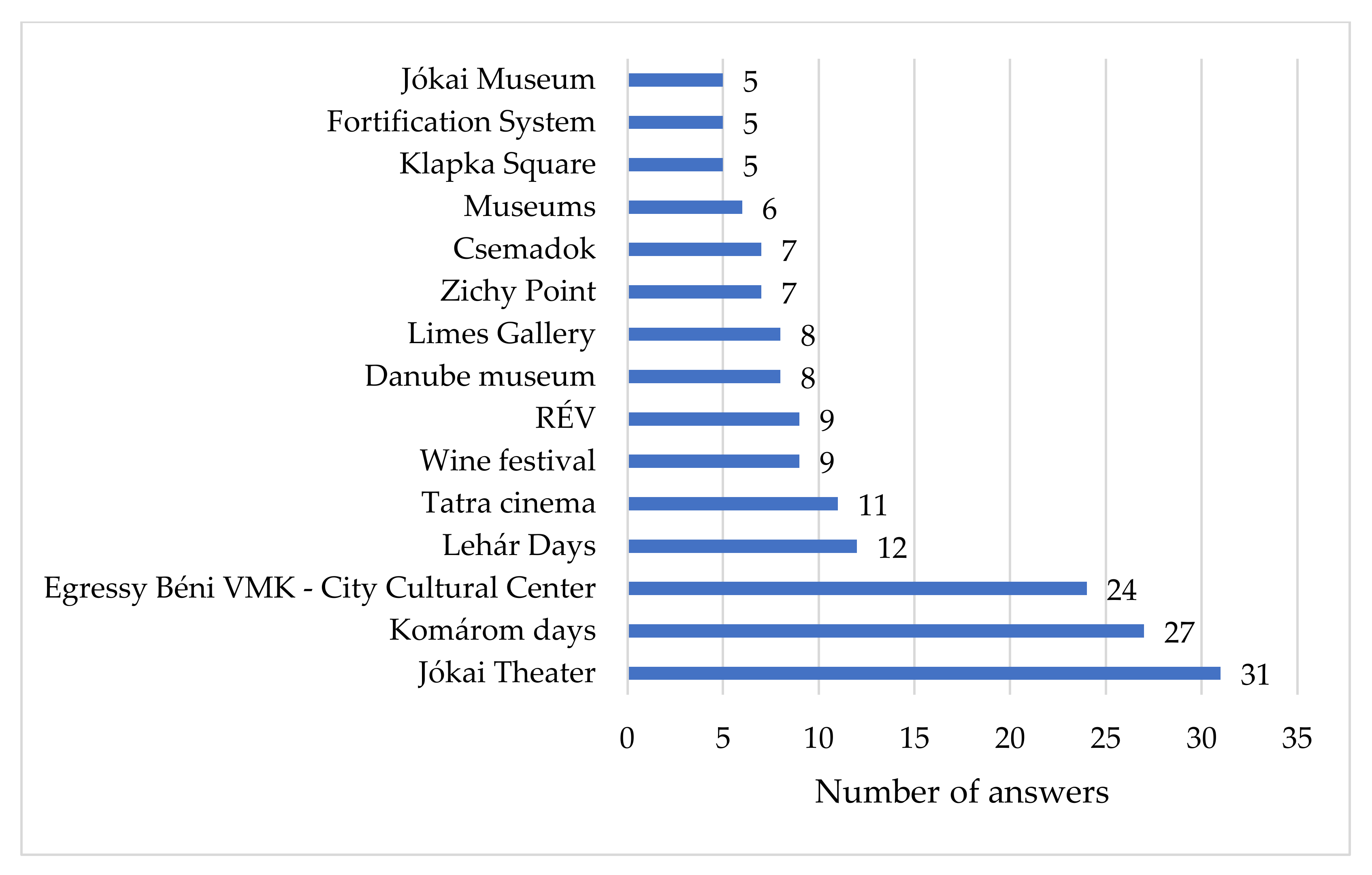

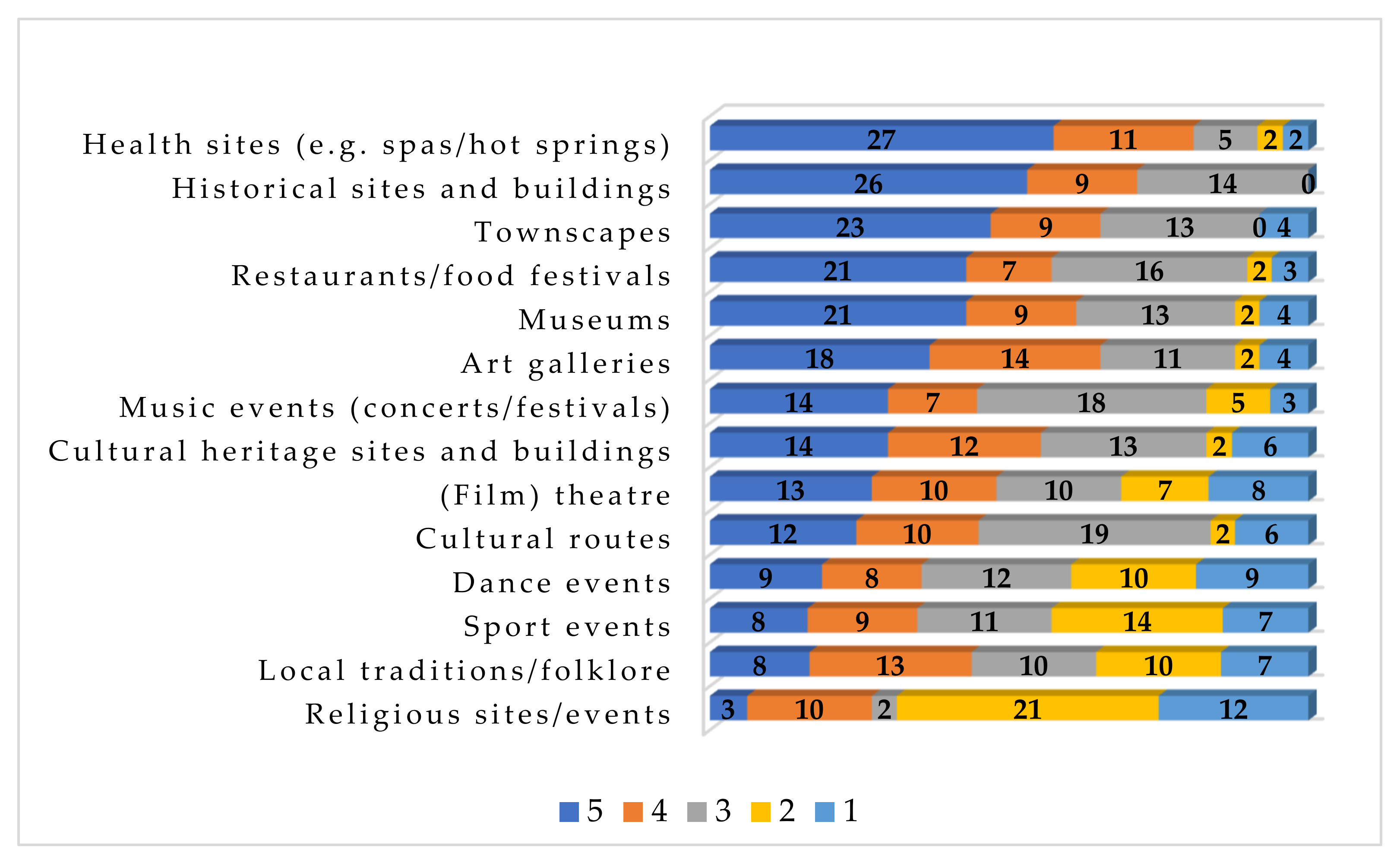

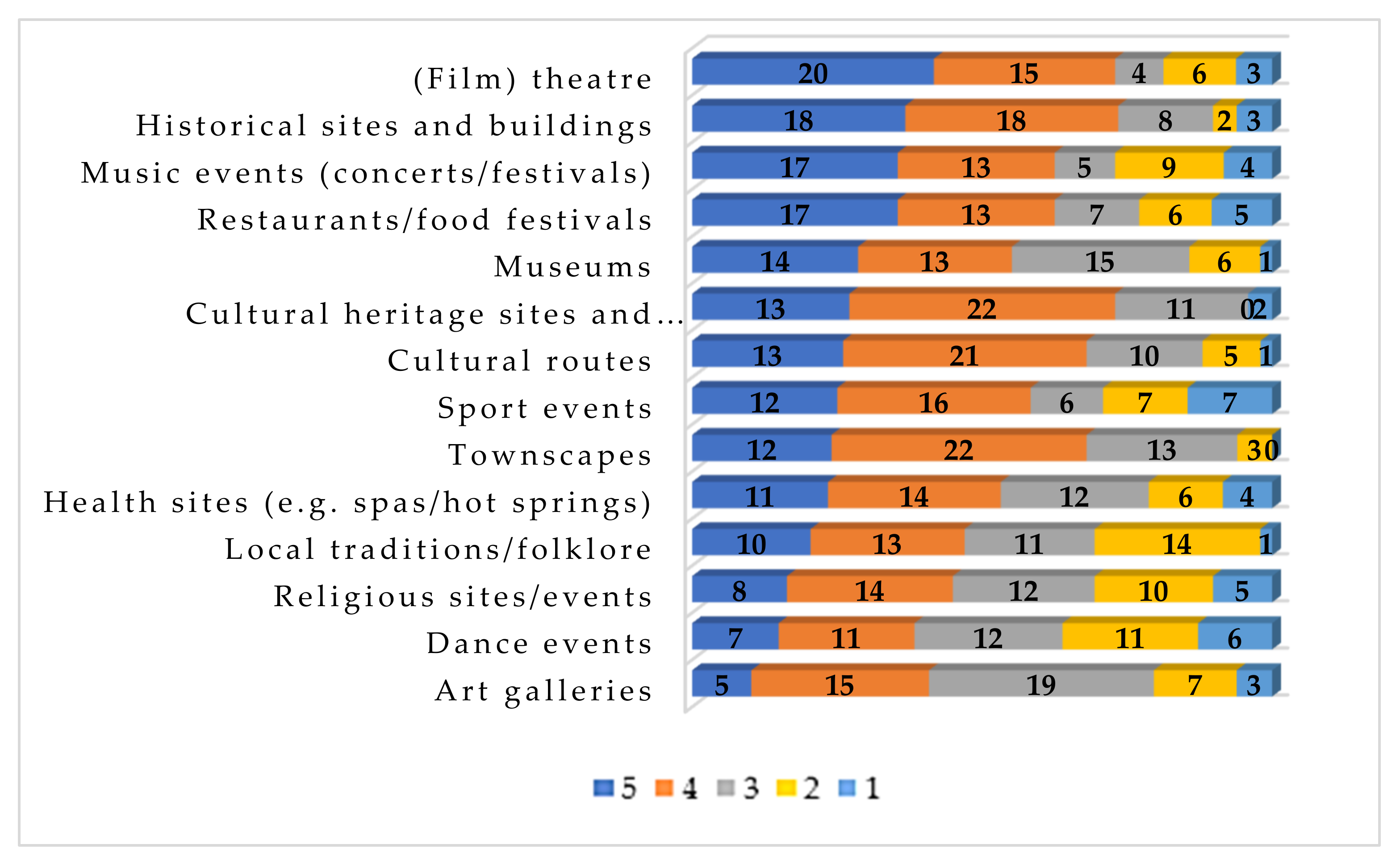

One of the two open-ended questions in the residential survey focused on the perceived popularity of cultural activities and sites. The cultural activities and sites most frequently mentioned by residents were the Fortification System, the Komárom Days, Jókai Theatre, museums, RÉV Centre, and the Lehár Days. Museums, like the Klapka György Museum, were also mentioned frequently. Looking at the differences (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), Hungarians considered the Fortification System the most popular cultural site, followed by festivals and wellness sites.

As they perceived the Fortification System to be the most popular cultural site, we can determine that residents see it as one of the most important elements of the uniqueness that is marketed for tourists. It is a core element of the former Hungarian Kingdom and Austro–Hungarian Monarchy as well. The Old and New Fortresses resisted the largest armies of the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg troops in 1849 during the Hungarian independence war. Interestingly, the residents of Komárno did not consider the Fortification System to be as important.

The reason for that could be that its most visited parts are found in Komárom. In Komárno, the most popular cultural site is the Jókai Theatre, which is one of the two Hungarian-speaking theatres in Slovakia, a highly frequented venue by Hungarians living in the city and in the cross-border region. It is considered to be one of the best-known cultural sites in the city and relates to the preservation of the Hungarian identity. Residents perceive the Komárom Days, Lehár Days, and Wine Festival as the most important cultural activities in Komárno.

The town gave birth to one of the greatest Hungarian writers, Mór Jókai, and the globally known composer, Ferenc Lehár. We can determine that the theatre and the festivals related to these well-known people are important parts of their cultural identity. Cultural heritage events, like the Komárom Days and Lehár Days, are common cultural elements and important joint festivals in the city pair as well. Based on the resident perceptions, we concluded that the cultural uniqueness of Komárom lies in the Fortification System and its festivals, while the cultural uniqueness of Komárno lies mainly in its festivals and in the theatre.

When analysing cultural tourism, it is important to examine the interactions between tourists and locals and how it impacts the life and cultural identity of the local people. To research the host community perceptions regarding cultural tourism, we first assessed their opinion about the number of tourists and the impacts of cultural tourism. Residents had to choose one of five options indicating their perception of the number of tourists (

Table 2). On the 5-point Likert-scale, 1 implied a very low and 5 a very high perception. The average mean of the residents’ perceptions was 3.19, which implies that they think that the number of tourists is neither high nor low.

The standard deviation of 0.85 implies a high variation in the data. Residents in Komárno, on average, perceived the number of tourists to be lower than residents of Komárom; however, amongst their answers, there was a higher variation than amongst the residents of Komárom. Only around a third of the respondents felt that the number of tourists was high, and only two of them perceived the number to be very high. The mean value of their answers and the standard deviation indicates that the number of visitors is beneath the threshold of perceived overtourism. The results may suggest that there is a desire for well-managed and limited tourism growth especially among the residents of Komárno.

When asked about the effect of tourism on their daily lives, 68% of the residents said that they are only minimally affected or do not feel any kind of negative effect from tourism.

Table 2 presents the mean values and the standard deviations of their answers. Those who felt that they were strongly affected chose the option 5 on the Likert-scale. Based on their answers, most of the residents did not have to deal with tourism-related nuisances.

Only three of them said that they were greatly affected in their daily life, and eight people answered that they were somewhat disturbed—out of them, six were residents of Komárom. Out of the 43 respondents who did not have to deal with any kind of negative effects, 63% were residents of Komárno. The results in

Table 2 indicate that there is not a significant difference in their perception, the residents of Komárom perceived tourism-related nuisances to be slightly higher than the residents of Komárno. Based on their answers, we concluded that the interactions between tourists and local people were mostly positive.

When asked about the relation between local traditions and tourism, the majority of the residents (65 respondents) thought that tourism had an impact on local traditions and to a certain extent effected the local culture (

Table 2). Respondents who chose 5 felt that it had a positive impact, while those who chose 1 indicated a negative attitude. Altogether 63% of them felt that tourism effected local traditions positively. The mean value of their answers was 3.81, which indicates a generally positive evaluation of the impact cultural tourism had on local traditions. The residents of Komárno perceived its impact more positively, but their answers had a higher variation.

Although the survey did not address the concrete effects of tourism on local traditions, previous findings showed that “most of the common positive impacts of tourism on culture include increasing cross cultural interaction; understanding, maintaining and keeping local culture, arts, crafts and traditions; empowering host communities; and strengthening cultural values” [

71].

In the case of the cross-border area of Komárom and Komárno, we are talking about culturally similar groups, visitors from the other side of the border are not searching for ‘the otherness’ [

44] as a commodity to consumed, on the contrary, they are mostly interested in the joint history and cultural heritage of their ancestors. This, in turn, leads to the will to preserve the cultural and ethnic heritage amongst the residents; however, as Picard (1995) argue, their cultural identity will continue to be of significant importance to them regardless of the presence of cultural tourists.

To assess the residents’ perceptions of the impact of an increase of cultural tourism, a 5-point Likert-scale was used. The responses were quantified in such a way that 1 implied a negative and 5 implied a positive attitude regarding the issue being addressed. The choice of an intermediate answer (3) meant a neutral attitude.

In line with the previous findings, the results in

Table 3 show that the residents were generally in favour of further tourism development and had a positive perception of the impact that the increase of cultural tourism had on the area. A total of 75% of them thought that an increase would have a positive or a very positive impact on the area. We found that 17% of the respondents chose option 3, indicating a neutral attitude. Looking at the differences, the mean value shows that residents of Komárno foresee a more positive impact than the residents of Komárom. In general, we can conclude that cultural tourism in the area does not carry the risk of staged authenticity to meet the expectations of the visitor [

42].

4.4. Cultural Tourism in the Area

According to Negrusa and Yolal [

72], “cultural tourism is motivated by tourists’ interest in historical, artistic, scientific or heritage offering by a community of an area”. Tighe [

25], as discussed previously, came to the same conclusion. In order to assess the motivations of the visitors in the area, tourists were provided with a pre-defined list of motivations. In line with Tighe’s [

25], Silberberg’s [

24], and Richards’s [

23] definitions, the findings of the tourist survey showed that history/archaeology and local culture/traditions were the leading reasons for visiting the region. A total of 70% of the respondents marked these as their main motivations, followed by nature and landscape (

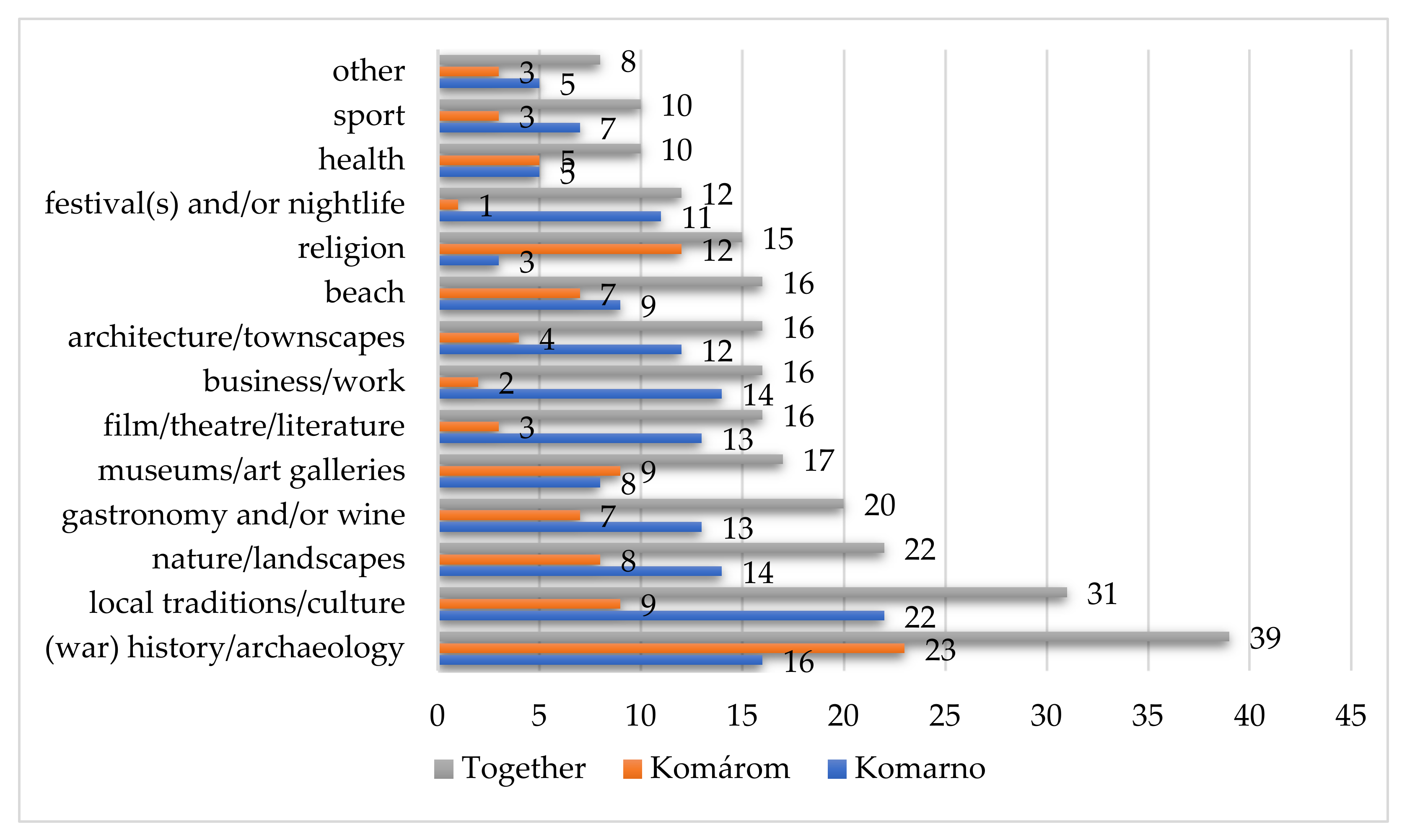

Figure 4). This result highlights the importance of the historical and cultural aspects of the area.

Most of the tourists visiting Komárom were interested in history and archaeology, while tourists visiting Komárno were more interested in the local traditions and culture. This might be related to the cultural uniqueness of the two cities. The most popular cultural site in Komárom is the Fortification System, which is generally a destination for those interested in history. The Roman Limes is another important archaeological site attracting many visitors. The tourism offerings in Komárno are more focused on “high” culture with sites, such as the Courtyard of Europe, the Jókai Theatre, festivals related to local traditions and gastronomy, such as the Wine Festival, and festivals related to folk music.

Since tourists consume different cultural tourism products and services and return visits are desirable for strengthening territorial integration, it is important to “identify variables that encourage the motivation, behavior and satisfaction levels of tourists” [

73]. Tourists were asked to compare their expectations about the area with their actual experience and indicate their satisfaction on a 5-point Likert-scale, in which 5 represented a high level of satisfaction (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). We found that 44% of them thought that the tourism offerings of historical sites met their expectations.

A total of 38% of the respondents were very satisfied with the quality of the restaurants and with the offerings of wellness sites. Tourists were least satisfied with the religious sites/events. There were 26% of the visitors who scored religious sites with 1, and 22% scored them with 2. We found 11 people who said that they had high expectations about local traditions and folklore but that their experience did not meet their expectations and scored them with 1.

These weaknesses need to be addressed, especially because dissatisfied tourists are not likely to return and would not be willing to recommend the area as a travel destination. A possible development opportunity is in increasing the focus on music, dance events, and festivals that incorporate elements of the local traditions and folklore. Sites, like the Fortification System, already give a place for festivals, and the increase of the number of events could lead to more satisfaction amongst tourists and would, in general, attract more visitors.

A high percentage of visitors in Komárom were motivated by the historical and heritage offerings of the city, and more than half of them were very satisfied with the historical attractions. While health was not the main motivating factor, respondents were the most satisfied with the health sites. The second most important motivation for visitors of Komárom was religion; however, they expressed the least satisfaction with the religious sites. In conclusion, respondents were generally satisfied with the core elements of the cultural offerings. Visitors of Komárno had cultural motives, such as visiting cultural monuments and exploring local traditions, as well as studying nature. They were the most satisfied with the theatre and historical sites, but only 20% of them were satisfied with the local traditions and folklore. Just as in the case of Komárom, tourist were the most satisfied with the core elements of the city’s cultural offerings.

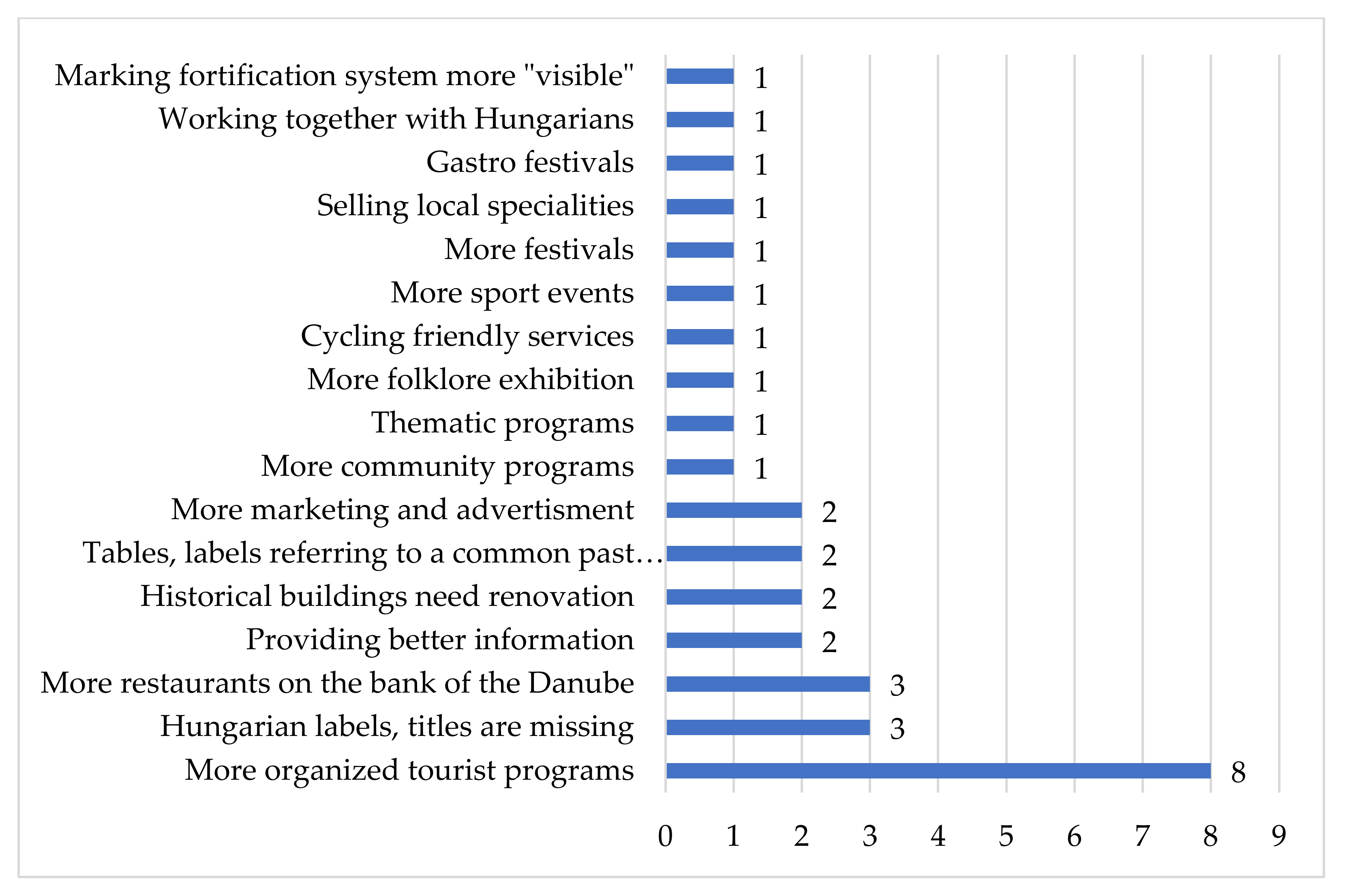

To identify areas that require development, tourists were asked to list missing tourist facilities and areas that, in their opinion, need improvement both for Komárom and Komárno. According to the results, the three key issues are the missing Hungarian labels and titles on the Slovakian side of the case study area, insufficient information, and the deterioration of historic buildings.

The question of replacing the missing Hungarian-language inscriptions features prominently among the improvements needed. We should add that this is a traditionally recurring criticism among tourists visiting the areas annexed from Hungary. In the case of Komarno, this criticism is also strange because almost everywhere, all relevant information is written in Hungarian as well. While previously, we concluded that tourist–host interactions were seen positively, the question of missing Hungarian-language inscription shows that they can still be vulnerable to misinterpretation and stereotyping [

46].

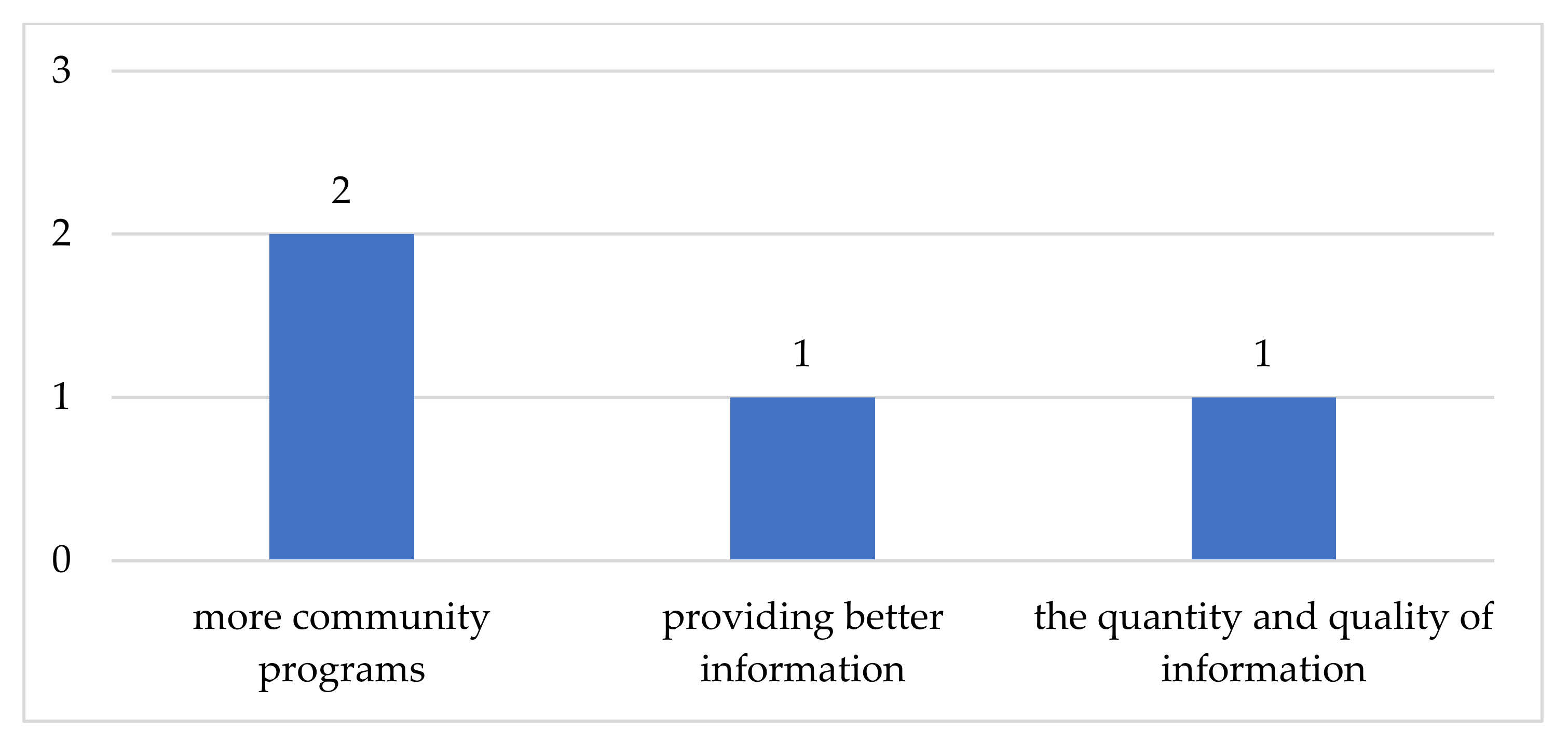

Tourists most frequently suggested providing more opportunities, e.g., providing more tourist programs, more sports events, and more festivals. As seen in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the tourists interviewed in Komárom considered the lack of information and the quality of information as the biggest problems; however, this was a prominent point in both samples. Based on the results, we identified the lack of tourism marketing skills and experts and the lack of investment in tourism marketing as the main barriers to the development of cultural tourism in the area.

Most of the visitors (71%) were tourists that had visited the area before. This is an important indicator of tourist satisfaction and loyalty to the area and supports the result that most of the tourists were satisfied with their experiences gained earlier in the area. Out of the 28 respondents who did not visit the area before, 24 would recommend visiting the area to others. There were 85% of those who visited the area before who were very satisfied or satisfied with their visits (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Only two respondents indicated that their experience did not meet their expectations.

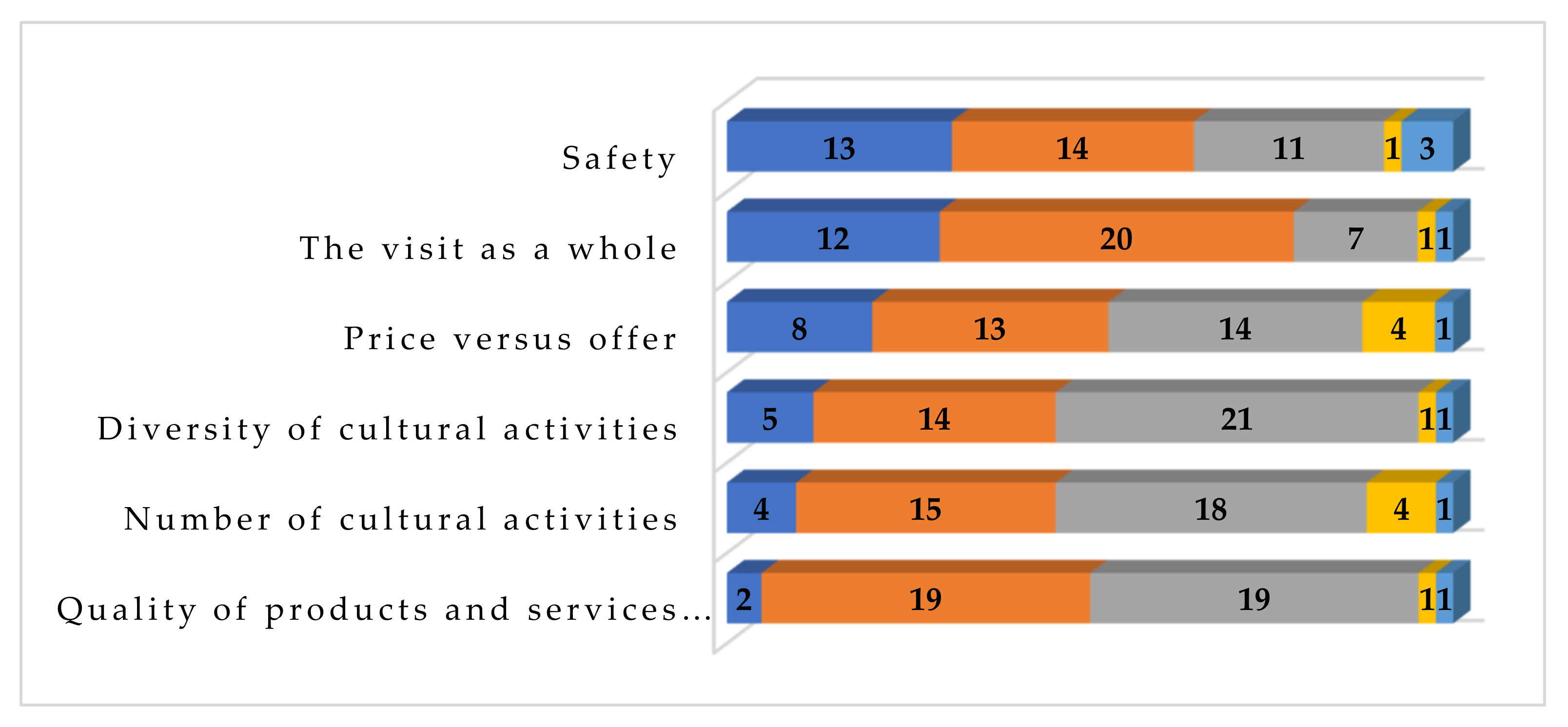

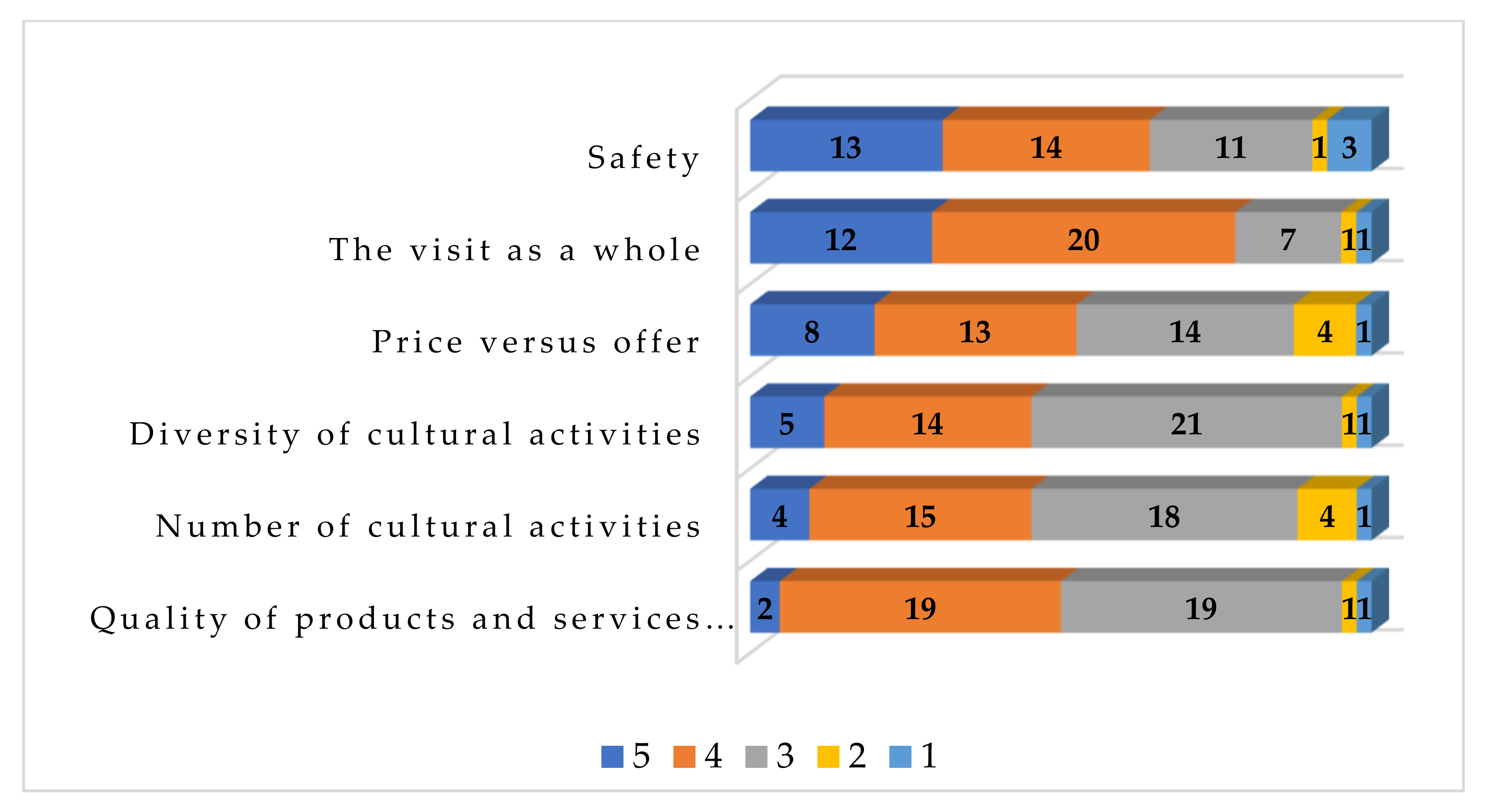

Overall, the number of cultural activities was the category that included the most negative responses. Of the factors affecting the overall experience, safety had the highest scores. Safety and price vs. offerings were the categories with the greatest variation in responses. Tourists interviewed in Komárom were more satisfied with safety than with their visit as a whole. Altogether, tourists in Komárno were more satisfied with the diversity of cultural activities.

A total of 19 out of the 50 respondents were very satisfied or satisfied with the diversity (

Figure 10); in contrast, out of 49 tourists visiting Komárom, only 15 were very satisfied or satisfied (

Figure 9). Similar results were obtained for the number of cultural activities. These results are in line with the general cultural offerings of the cities and show that the tourism offerings of Komárno are focused more on cultural activities, whereas Komárom’s main tourism offering is about passive activities, e.g., sightseeing.

5. Conclusions

In our study, we examined a cross-border tourist destination: the cross-border city pair of Komárom–Komárno located on the two sides of the Hungarian–Slovak border. The aim of this study was to examine cross-border tourism in an area in which the visitors crossing the border represent two different identities but are members of similar cultural groups. The analysis of the results focused on the main characteristics of cultural tourism in the area, and the future research direction is a more in-depth comparative analysis of the data building on the results of partners in the project consortium.

From our research, we can conclude that tourists had different motivations for seeking out twin-city attractions. It was also possible to distinguish a group of visitors who visited Komárom primarily for the historical and archaeological sites. Based on our research, they were mainly Hungarians from Hungary and residents of Slovakia interested in the history of their ancestors.

This finding supports the research hypothesis that, in a symbolic place of national cultural heritage, such as Komárom/Komárno, the cultural values, monuments, and heritage sites are the strongest attractions for nationality-based cultural tourism. Historical buildings form the main cultural offerings of Komárom, and its core element is the Fortification System. In Komárno, cultural festivals and theatre—especially the Hungarian-language theatre—are the core elements of the cultural offerings. The different focuses of their cultural offer supports that the borders are still having an impact in this respect: cross-border cultural and heritage tourism destinations have not been integrated.

While the survey did not adhere to the criteria of representativeness, the research results may offer valuable information for policy-makers and destination managers. Due to the pandemic and its aftermath, experts forecast an increase in domestic and regional cross-border tourism, while international tourism is expected to take longer to recover. Therefore, in the recovery phase, it is important for destinations to be aware of the motivations and particular interests of domestic and regional cross-border tourists.

In terms of the adaptability of the research results for policy-making and development activities, one can conclude that the tourist attractions of a cross-border area can better be marketed in an integrated way, especially in those cases where the neighbouring territories once formed part of an integrated region. Komárom and Komárno represent two parts of a unique and common cultural heritage even if, during the last century, the two towns have developed in two different directions—both in economic and social-cultural terms. The low effectiveness of INTERREG CBC programmes is partly due to the lack of integrated tools.

As a consequence, culturally, historically, and geographically coherent destinations cannot be developed in an integrated way: the local actors realize separate projects that have no shared elements and do not use the potential synergies. Instead of supporting stand-alone projects, the CBC programmes should incentivize those initiatives aiming to unite the attractions from the two sides of the border. At the same time, local actors should be encouraged to design their tourist destination in common as a single and unique tourist product. The application of this integrated approach is easily manageable in regions where the geographic proximity is further boosted by cultural-ethnic similarities and a (partly) shared identity.

In the case of Komárom and Komárno, it is essential for integration that the two regions, which currently function separately, draw up a strategic tourism concept together as there is a clear potential for integrated cultural tourism development in the area. The attractions present in both cities could place the common destination on the tourism map of Europe.

The coordinated development and tourist use of the fortress system, the Roman heritage theme, the memory of one of the monarchy’s most important and popular composers, the involvement of the cities under the umbrella of cultural routes (e.g., the Cyril and Methodius Route), and the further enhancement of the tourism importance of the Danube and shipping could all play a role in this. Together, these could raise the tourism of the twin cities to a truly international level and give them a symbolic reputation—a ’brand’ that would transcend the ethnic divides of the 20th century.