Abstract

Shade-grown coffee is an important reservoir for tropical biodiversity, but habitat quality hinges on decisions made by farmers. Our research aims to investigate the link between coffee producers’ decisions and outcomes for biodiversity, using epiphytes as our focal group. Using qualitative methods, we interviewed 33 producers in northern Nicaragua to understand how they connect trees and epiphytes on their farms to ecosystem services and how personal values, access to agronomic expertise, labor supply, and financial stability influence decision-making. We used interview responses to construct six producer typologies. Most producers had strong positive attitudes toward trees and associated them with a variety of important ecosystem services. Smallholders were more likely to connect trees with provisioning services, while producers on larger farms and with greater agronomic knowledge emphasized regulating services. Most producers connected epiphytes primarily with aesthetic values. Across demographics, producers emphasized the restorative potential for shade coffee in repairing damage to soil, water, and nutrient cycles caused by other forms of agriculture. The conservation significance and sustainability of this social-ecological system can be maintained and expanded through economic and capacity-building conservation interventions, especially when those can be connected to values already held by farmers.

1. Introduction

Shade-grown coffee has attracted considerable attention as a social-ecological system and a land-sharing practice [1,2]. It can support high levels of biodiversity, provide ecosystem services, and improve the livelihoods of producers [3,4,5]. Shade coffee is an umbrella term for any coffee cultivation system that adds trees, and it encompasses a wide spectrum of practices from “technified” plantations—intensively managed farms with one or a few shade tree species—to “rustic coffee,” which is planted in the understory of thinned forest trees [6].

The biodiversity benefits of adding shade to coffee systems extend across diverse taxonomic groups, including birds [7,8], invertebrates [9], trees [10,11], and epiphytes [12,13,14]. Epiphytes, our focus in this study, are non-parasitic air plants, including orchids, bromeliads, ferns, bryophytes, and lichens, that grow without connection to the soil, depending on trees and shrubs for structural support. Epiphytes are highly diverse, representing up to half of all plant species in tropical forests [15], and readily inhabit open-grown trees in pastures, urban areas, and agroforestry systems, including coffee farms [12,16,17]. Producer attitudes toward epiphytes are largely unknown but may be neutral or negative based on epiphyte removal as a common practice in coffee farms in some countries [18,19]. However, aesthetic appreciation of epiphytes, especially orchids, has also been noted among coffee farmers [20].

Coffee supports the livelihoods of millions of smallholder farmers worldwide, but much coffee production also occurs on large plantations [21]. Small farms and plantations coexist spatially, resulting in a landscape mosaic of wealth inequality, and these farms differ in their economic situations, relative exposure to risk, and attitudes toward production [6,22,23]. Large plantations have financial reserves to last through the year, little constraint to borrowing, and are better positioned to take advantage of certifications, direct market relationships, and technological innovations to gain access to higher coffee prices. Primarily due to the rugged topography of coffee-growing regions, coffee production is not well suited to mechanization, and large and small farms alike rely heavily on human labor for planting, managing, and harvesting coffee and pruning shade trees [24]. Large farms are production-oriented with an entrepreneurial focus on responding to markets; smallholder farming, on the other hand, is internally focused on sustaining the livelihood of the family [3,23]. Because coffee is harvested once annually, smallholders who grow coffee as their primary or only revenue source face many months without income and credit constraint, inducing a hunger season and accumulating debt [25,26]. Smallholder livelihoods risk becoming increasingly marginal as global coffee prices decline, coffee disease threats intensify, and climate warming pushes coffee plants toward their thermal limits [26,27].

Adding trees to coffee farms offers ecosystem services that can help producers in a variety of ways, although there are also costs. Trees alter farm microclimate and nutrient cycling, providing key regulating services [1,4]. Shade lowers coffee leaf temperatures, limits plant water demand, and reduces soil evapotranspiration [4,28,29]. Leguminous trees fix nitrogen, increasing coffee productivity, and leaf litter from trees can increase soil organic matter and add nutrients [28,30]. However, shade cover may decrease annual yields, especially at higher levels, and the area used for trees trades off with coffee shrub density, which also reduces yield per cultivated area [29,31]. Pruning and management of shade trees add labor and lost opportunity costs [24]. Even so, the scientific literature largely suggests that the improved soil nutrition and water retention, decreased erosion, and increased resilience to climate change should provide a net benefit to farmers [4,29] (but see [32]). Agroforestry also offers provisioning services to farmers, including timber, firewood, and fruit for subsistence use [3,20,33,34]. These benefits should be particularly important for smallholders to help offset financial shortfalls. Finally, trees can add cultural services to farms, including aesthetic values and opportunities for ecotourism [6,20].

While ecosystem services associated with shade coffee cultivation methods have been well documented ecologically, surprisingly little work has examined how producers actually perceive and weigh the costs and benefits of trees, and their motivations for beginning or maintaining shade coffee production are unknown. Several studies have considered producers’ uses for trees and perceptions of ecosystem services [28,33,34,35,36,37], but few have attempted to connect producers’ values and economic motivations with management. Further, while the ecological literature has linked specific management practices to biodiversity indicators, whether producers value biodiversity on their farms is not well understood [6,38]. Such information is critical for successful outreach to producers and designing interventions to improve conservation and producer livelihoods [39,40]. Thus, we use a primarily qualitative approach to inductively uncover producers’ motivations and perceptions to fill this gap. Based on previous work, we expect producers’ decisions to be influenced by a combination of their financial stability, labor supply, access to agronomic expertise, and values for nature and biodiversity [3,20,22,24]. We predict the relative strength of these influences will vary by farm size, which is presumably associated with wealth and social capital [21]. Our work compares small vs. large farms, asking the following research questions:

- What benefits, costs, and services do producers perceive from trees and epiphytes?

- What are the relative roles of financial stability, labor supply, access to agronomic expertise, and personal values in motivating producers’ decisions regarding shade trees and epiphytes?

- Is farm size a useful proxy for differences in financial stability, labor supply, and access to agronomic expertise?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Producer Interviews

In April–May 2018, we conducted 33 semi-structured interviews with producers on 31 coffee farms employing shade cultivation in northern Nicaragua (Figure S1). Farms ranged in size from 1.4 to 490 ha. We classified farms as “large” if they equaled or exceeded 13 hectares in size, following Bacon’s [21] farm size divisions for previous work in the same region of Nicaragua but combining his “medium” (13–30 ha.) and “large” (>30 ha) classifications due to the similarities in economic measures he documented. Farms 13 ha. or larger make up only about 5% of Nicaraguan coffee farms [21] but represented half of our sample to allow for comparisons based on size (large: n = 16, small: n = 15).

Twenty-nine of the farms in our study had been given trees as part of a previous project led by the American Bird Conservancy (ABC). The researchers had prior connections to the remainder, which were included to increase the number of large farms. Because producers had self-selected for the ABC project, we expected they would exhibit positive values for nature, biodiversity, and trees at a higher rate than the general population of coffee farmers in our study region. However, our research goals necessitated talking with producers who already had committed themselves to shade coffee to gain insight into why they had done so.

Interviews ranged in length from 15 min to 2 h. Each interview was recorded and later transcribed. All interviews were conducted in Spanish, except for one conducted in English. This research qualified for IRB exemption from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Education and Social/Behavioral Science IRB. We used standardized closed- and open-ended questions in each interview (Appendix A), but additional follow-up questions differed. In one case, father and son on one farm were both interviewed; in another, the owner and farm manager on one farm were both interviewed. Some farms adjoined each other, and several had familial connections between them. Interview topics included basic farm information, management practices, financial situation, uses and benefits of trees, perceptions of climate change, and attitudes toward epiphytes. In addition to the formal interview, most producers accompanied us during field measurements, and informal conversations often occurred. Notes from these conversations and impressions of the farm were recorded at the end of each day and used to inform the analysis.

2.2. Ecological Measurements

On each farm, we established two to five 400 m2 plots. In each plot, we measured diameter at breast height (dbh), height, and species identity (common name provided by the farmer) of all trees, measured coffee shrub density, and counted vascular epiphytes. These plots document the spectrum of management practices across all farms in the study and their effect on epiphytes. We present the full methodology and the ecological results of these measurements in two previous papers [14,41] and only use these data here in reference to the tree species farmers planted on their farms and the coffee planting density.

2.3. Analyses

We used primarily qualitative methods to analyze interview data. To evaluate the ecosystem services farmers perceive and their motivators for management decisions, we manually coded interview transcripts using structural coding [42]. We first coded interview segments thematically, based on preordained categories related to our research questions: uses and perceptions of trees, attitudes toward epiphytes, financial situation, farm management and operations, and perceptions of climate change. We assembled all responses within a thematic code and conducted a second round of coding, this time using descriptive coding arising from the responses. For example, the uses and perceptions of trees category was subdivided into 18 discrete perceptions, each expressed by at least one respondent. The third round of coding further interpreted the responses within each of these subcategories to unearth the producer logic behind each perception and explain how each factor influenced producers’ decisions [42]. For the responses related to uses and perceptions of trees and epiphytes, we tallied the number of respondents who mentioned each one. Quotes included in this paper were translated from the original Spanish by the authors (Appendix B).

Many of the close-ended interview questions we asked lent themselves to a quantitative interpretation. To relate farm size to the producers’ economic and social characteristics, we employed descriptive statistics to examine patterns among our respondents and to group respondents into typologies [22]. These are not meant to be representative of all coffee farmers in our study region and are instead presented to summarize commonalities and differences among our respondents useful to the interpretation of the qualitative analysis. We created binomial variables (1 = yes, 0 = no) for other farm income, off-farm income, loans for subsistence, loans for farm investment, and cooperative membership. Agrochemical intensity, income from coffee, access to markets, and access to agronomic expertise were each assigned to an ordinal scale based on interview responses as follows: Agrochemical intensity (1 = few agrochemicals used, typically use organic alternatives, 2 = chemical fungicides and fertilizers used, and herbicide used sparingly, 3 = fungicide, herbicide, and fertilizer all used regularly, and insecticide used only after other methods have failed or not used at all, 4 = no restraints indicated on chemical use); access to markets (1 = sells in a local market, 2 = sells to cooperative, 3 = sells to export company, 4 = direct market relationships abroad); access to agronomic expertise (1 = credit assessor from a bank or cooperative sometimes offers agronomic suggestions to improve production; 2 = agronomic technician provided by a cooperative for members; 3 = family member or friend with agronomic knowledge advises farm management; 4 = farm manager or owner is an agronomist). Numerical values for land area in coffee, farm age, number of permanent workers, coffee planting density, and months of financial insecurity were also extracted. For farms where two respondents were interviewed, their responses were combined for quantitative analyses so that each farm was included once. To test whether the delineation of large vs. small farms that we had originally assigned matched the most important qualitative differences among producers that arose in our interviews, we used ANOVA and linear regression analyses to compare farm size to the numerical variables we extracted from the interviews. We treated farm size as categorical based on our original categorization of small vs. large farms but also evaluated total farm area as a continuous variable. Farm size, farm age, and the number of permanent workers were log-transformed to meet the assumptions of our statistical models.

To better understand how financial stability, labor supply, and access to agronomic expertise contributed to decision-making, we used these quantitative variables to develop farm typologies based on multiple factors using hierarchical cluster analysis [22]. We performed agglomerative clustering using the hclust function in R with the Ward algorithm designed to find compact, round clusters based on a distance matrix. We used Gower’s distance from the R package ‘FD’ [43] to calculate the distance matrix because it allows for missing values and the inclusion of binomial and categorical variables. We calculated distance based on farm size, land area in coffee, farm age, number of permanent workers, coffee planting density, agrochemical use intensity, household income from coffee, other farm income, off-farm income, loans for subsistence, loans for farm investment, months of financial insecurity, cooperative membership, access to markets, and access to agronomic expertise.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Farm Size and Typologies

Farms averaged 56.7 ha in size. The median, 14 ha, better characterizes most of the farms we visited and aligns well with our division of small vs. large farms (13 ha). Small and large farms differed in percent of land in coffee cultivation, coffee planting density, months of financial insecurity, use of loans, market access, and access to agronomic expertise (Table 1). The amount of land in coffee production decreased with farm area (t = −4.07; p < 0.001). As farm area increased, so did the number of permanent workers (t = 6.75, p < 0.001), level of agronomic expertise (t = 3.49; p = 0.002), and access to markets (t = 4.83, p < 0.001). Farm area also negatively predicted the months of financial insecurity producers experienced (t = −3.09, p = 0.005) and coffee planting density (t = −2.44, p = 0.02). Agrochemical use showed no relationship with farm size, but we did find a negative relationship between agrochemical intensity and access to agronomic expertise (t = −4.72, p < 0.001). Farm area was not correlated with farm age, indicating that land is not necessarily accumulated over time.

Table 1.

A comparison of farm metrics between large and small farms. Asterisks indicate significance levels based on t-tests (* = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01). ǂ indicates ordinal variables on a scale of 0–4, § indicates binomial variables (1 = yes, 0 = no).

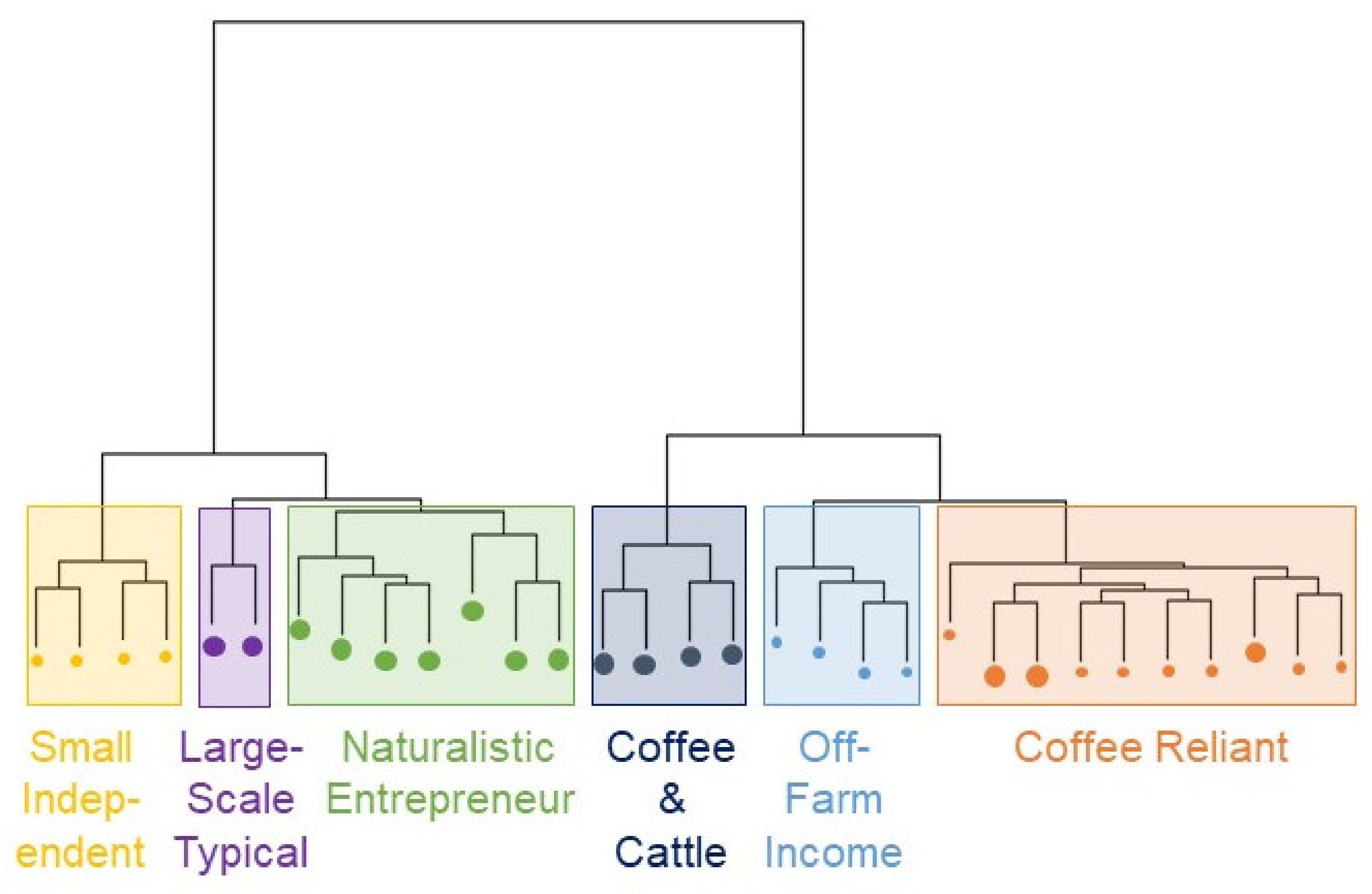

While there were clear patterns based on farm size, we found that dividing farms based on size alone failed to capture many important differences among the farms. The hierarchical cluster analysis better characterized producer groups, and clustering into six typologies provided the most internal consistency (Figure 1). We describe each typology based on interview responses (Table 2). These typologies reveal several key differences among respondents obscured by looking at farm size alone. For example, while most small farms depended heavily on credit, we encountered several smallholders who were extremely debt-averse (Independent Small Producers) and took credit as only a last resort, expressing fear of losing their farms. Large farms generally had better access to agronomic expertise, but we also encountered very large farms with lower agronomic expertise despite considerable economic resources (Large-scale Typical). Finally, producers who also raised cattle (Coffee and Cattle) and several producers in the Coffee Reliant group had enough land base to qualify as “large farms” according to our classification scheme, but they were more similar to smallholders in many other respects (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hierarchical cluster analysis dendrogram showing typology divisions based on the Ward clustering algorithm. Large filled circles indicate farms 13 ha or larger and small filled circles indicate farms smaller than 13 ha.

Table 2.

Farm typologies. The number of farms in each typology (n) is listed. Farm size includes the mean in hectares with the size range in parentheses.

3.2. Benefits and Services from Trees and Epiphytes

Producers cited 16 benefits and services associated with trees and two disadvantages (Table 3). They discussed trees in reference to coffee production (88% of respondents) and ecosystem services, particularly provisioning services (88%) and regulating services (81%). Despite living in a region with some of the highest epiphyte diversity in the world, many producers had never given epiphytes much thought. Producers named considerably fewer benefits and services provided by epiphytes, and their responses focused on cultural services, including aesthetic appreciation (36%), attracting wildlife (36%), and the recreational and touristic values of cultivating epiphytes (18%).

Table 3.

Values for trees based on interview responses (total number, with percent of responses indicated parenthetically). Typology is if more than half of the respondents in that group mentioned the value.

Producers differentiated among tree species and epiphyte groups in their responses. They assigned different uses to various tree species (Table S1) and sometimes planted trees that they believed were not favorable for shading coffee because they relied on them for other purposes. This is a common phenomenon among coffee producers, and the abundance of each species overall should reflect the degree of benefit farmers associate with it [37]. Similarly, producers differentiated groups of epiphytes, with orchids being the most highly regarded for their aesthetic and recreational value and bryophytes being most connected with negative impacts on coffee [19,20].

3.2.1. Effects of Trees and Epiphytes on Coffee Production

Producers felt that shade improved coffee plant health (70%) and enhanced coffee flavor and cup quality (36%). However, they also believed that too much shade could be just as damaging to the coffee as too little, citing decreased production (27%) and increased fungal disease (42%) as the main problems. Producers observed that plants in the full sun showed more signs of stress with yellowed leaves or leaf loss during the dry season and smaller, drier fruits. They reported that while coffee grown in the sun has higher yields initially, production decreases after 2–3 years, requiring plants to be cut back and allowed to regenerate (as opposed to 3–5 years under shade cultivation). Economic losses in production under shade cultivation can be compensated by a higher price point for the improved quality of the coffee [29], a point recognized especially by Naturalistic Entrepreneurs. With slower growth under shade, producers explained, better flavors develop because the fruit matures more slowly and has more mucilage, and the bean is larger and “more beautiful”:

“If the bean takes longer to mature, it picks up more nutrients and it has a better taste in the cup, while if it is exposed to the sun, it is stressed more and throws all its energy to the bean, which matures faster and, in the case of the quality of the cup, I think it’s not good”(Naturalistic Entrepreneur).

Because coffee plants in full sun grow faster and yield more, they also require more nutrient inputs, increasing fertilizer costs for farmers. Conversely, when not enough sunlight reaches the coffee, plants may look healthy but do not flower. All producers we interviewed told us that they preferred growing coffee under shade rather than in the full sun, but they qualified that it needed to be “regulated shade.” As one producer explained,

“The thing is you have to manage them [trees], you can’t just plant them in the coffee and let them do whatever they will… so you do some management so that they both can live there, because we need the trees and we also need the coffee”(Off-Farm Income).

Too much shade also increases humidity around the coffee plants and reduces the sun reaching the leaves, which producers explained causes a higher incidence of American leaf spot (Mycena citricolor). However, American leaf spot was only problematic at higher elevations. In warmer zones, producers struggled more with coffee leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix), which they did not associate with too much shade cover, indicating a belief that the appropriate amount of shade cover should differ by elevation.

Climate predictions suggest that coffee production is becoming less favorable in many regions where it is currently grown [27]. Many producers had observed climate changes, reporting hotter weather with a shorter cold season, more rain with stronger storms, and altered seasonality. These changes affected coffee production by provoking flowering and fruiting earlier than normal and changing the suitability of some coffee varieties for certain elevations. Producers also cited a higher incidence of disease from climate change, both for American leaf spot because of increased rain, and for coffee leaf rust, due to elevated temperatures. Nearly half (48%) of respondents identified shade trees as important in helping their farms withstand climate change by keeping the coffee cooler, reducing sun damage, and maintaining soil moisture. As one producer reports,

“The trees in coffee plantations help us to maintain a more homogeneous temperature within the plantation … I am a coffee crop consultant and I go to many coffee plantations … and we always see that it cushions the changes better, the climatic variability, when we have a number of trees in the coffee. That is undeniable”(Naturalistic Entrepreneur).

Several producers connected epiphytes, particularly bryophytes, negatively with coffee production and none associated epiphytes positively with coffee. Epiphyte removal from coffee shrubs and shade trees is a common management practice in other countries [18,19], but among our study participants, it was not the norm. However, several producers listed removing moss as part of their annual cycle of management activities believing that it damages coffee plants:

“When there is moss that takes root all over, it squeezes the producing plant too much and weakens the stem, and then it weakens the foliage, in the case of coffee. And then the humidity it produces, that produces fungus and it begins to do damage, that’s why everything must be controlled”(Coffee and Cattle).

Bryophytes have been shown to decrease coffee yield [19], although the mechanism has not been investigated. A few producers also assumed that epiphytes damage shade trees. One Naturalistic Entrepreneur appreciated all epiphytes except Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides), which she falsely believed kills trees, and she had instructed workers to remove it on her farm, although she allowed all other epiphytes to remain. In total, four producers (12%) admitted that they occasionally remove epiphytes from shade trees, although this practice seemed largely capricious and motivated by a lack of knowledge. As one producer told us, “Because we don’t know the importance they [epiphytes] have, sometimes we see them on the trunks and what we do is chop them off” (Coffee Reliant).

3.2.2. Provisioning Services

Producers discussed firewood, timber, and fruit as provisioning services provided by trees on their farms. The importance of these three services is recognized by smallholders across many tropical regions [33,36,37,44,45] and can provide up to half the economic value gained as cash income from coffee production [33]. The Naturalistic Entrepreneurs were the only group that did not universally discuss provisioning services, suggesting that the inclusion of trees in their farms is based on other benefits and values. The large farms in other typologies expressed the importance of provisioning services to their farms. Epiphytes were not typically associated with provisioning, although several respondents believed they could have medicinal properties. A Coffee and Cattle producer also told us he removed epiphytes from his trees and fed them to his cattle in the dry season when forage was scarce.

Cooking over wood fires is still the norm in this region except in wealthier households. The importance of firewood was mentioned by 82% of producers, including all respondents in the Coffee Reliant, Coffee and Cattle, Off-Farm Income, and Large-Scale Typical groups. Producers gathered firewood primarily from pruning shade trees but also used dead trees or the wood from pruned coffee shrubs. They cited the convenience of having a supply of firewood closer to the house, taking pressure off nearby forests, and not having the expense of buying firewood as benefits. Guabas (Inga spp.) were strongly preferred trees for firewood and were the most common shade trees in our study (Table S1).

Producers also harvested wood for construction and fenceposts from their farms, although with less frequency than firewood. They preferred different trees for timber, including walnut (Juglans olanchana), Spanish cedar (Cedrela odorata), and various types of avocado (Lauraceae spp.). Unlike in other regions [33], no producers in our study discussed selling the timber they culled from coffee plantations; rather, timber use was limited to one or a few trees only when the family needed to build or repair a structure or furniture.

Surprisingly, only five producers (15%) mentioned fruit production as a benefit, although this has been frequently reported in other studies [36,37,44,45]. Three producers (10%) reported selling bananas as an occasional source of farm income. However, in our tree surveys (Table S1), we observed bananas or plantains (Musa spp.) on 74% of farms, as well as avocado (Persea americana; 35%), citrus (Citrus spp.; 29%), mombin (Spondias purpurea; 16%), guava (Psidium guajava; 13%), mango (Mangifera indica; 13%), nance (Byrsonima crassifolia; 6%), soursop (Annona muricata; 3%), and mamey sapote (Pouteria sapota; 3%).

3.2.3. Regulating Services

Trees provide documented regulating services on farms, including sequestering carbon, retaining soil moisture and improving soil fertility [4]. Nitrogen inputs from leguminous trees can also offset fertilizer costs [30]. Producers recognized the importance of these services to their farms, with 81% mentioning one or more regulating services. The most common services discussed were improving soil (45%), water conservation (42%), and reducing erosion (21%). They also frequently mentioned oxygen production as a benefit of both trees and epiphytes. Regulating services were less associated with epiphytes, although bromeliads were named for their water storage capabilities (24%).

A surprising theme that emerged from our interviews was the restorative function of coffee farming, connected to regulating services provided not only by the shade trees but also by the coffee plants themselves. This idea transcended typology, although it was articulated somewhat differently among groups. Of the 87 plots we surveyed on all farms, 84% had been used for pasture or annual crops before conversion to coffee. Multiple producers described the transformation that had happened, indicating they felt the coffee was not only a better land use than other types of farming but could even undo years of damage from other agriculture.

For producers with greater access to agronomic expertise, particularly Naturalistic Entrepreneurs, these changes were related to soil moisture, fertility, and compaction. Their responses expressed a deep understanding of the ecological interactions occurring on their farms and how those interactions could be harnessed not only to improve coffee production but also to enhance environmental sustainability. They esteemed nitrogen-fixing leguminous trees and leaf mulch for adding nutrients to the soil, reducing the amount of chemical inputs they needed to apply. Leaf mulch also added organic matter that they said improves soil structure, feeds beneficial microorganisms, and retains moisture. One producer compared the environmental impacts of shade coffee cultivation to pasture:

“Okay, look, I think if we think about it calmly, coffee is a crop, a very noble crop and between having 50 hectares of pasture and having 50 hectares of coffee, I think we should have 50 hectares of coffee, because we have 50 hectares of trees. In 50 hectares of trees there are 200,000 trees that produce an incredible amount of leaf area, that transpire, that respire, that purify, that give better life, that retain more moisture in the soil. So, day by day, we can see these places where the farm was really arid, that when we converted them to coffee plantations and we put them in shade—because I am in love with that shade—it has changed enormously, you can already see the differences in the soil. In fact, in fact, if we didn’t have… I don’t know… the people who think there should be trees, we’d be screwed. I’m reforesting the creeks, I’m reforesting the water sources, the rivers, making living fences. Just last year, we put 2000 trees into a small farm like this one last year and we are doing all we can to try to make that work”(Naturalistic Entrepreneur).

Producers who did not have the scientific language to describe the ecological changes that had occurred nonetheless reflected on shade coffee as a solution to land degradation that they had inherited from previous landowners or caused themselves through other types of farming. One producer proudly showed us the soil conservation measures he had put in place and described how his land, degraded from years of annual tillage and erosion, had changed since planting shade coffee:

“… you couldn’t plant coffee here, the earth had been washed away, it had just a thin sheet of fertile soil, but as trees were planted new soil has been forming with the leaves that fall and the branches that rot adding to it”(Off-farm Income).

They also connected shade coffee to protecting and restoring water sources on their farms. One man’s eyes filled with tears as he described the springs that had been on his property historically coming back after he planted trees:

“There was a spring before but there were no trees and I planted trees and that spring came back, it reverted and better than before! With trees, I have now experienced it with two springs that are here…when I bought that [parcel], the previous guys had vegetables there, the soil was running away, and I planted coffee and the trees that are there and those springs returned and they returned even more opulent. The trees are helpful for life and for many things, for all of humanity, it could be said”(Coffee and Cattle).

3.2.4. Cultural Services

While producers mainly associated trees with provisioning and regulating services, they connected epiphytes with cultural services, and the attitudes expressed toward trees and epiphytes suggest underlying values for nature [39,46]. As previously documented [20], there was a strong aesthetic value for epiphytes, particularly orchids, among our respondents. They named the beauty and fragrance of the flowers as key assets that improved their farms. Multiple producers had collected orchids from fallen branches and pruning of shade trees that they cultivated near their homes to appreciate their beauty.

Producers also identified a touristic value for epiphytes. Several larger farms had or planned to establish collections of orchids on display for visitors. One Coffee and Cattle producer who also engaged in a small amount of ecotourism mentioned that orchids are promoted by the tourist bureau and should be protected for their touristic value. Respondents involved in tourism or with higher levels of education, particularly the Naturalistic Entrepreneurs, had greater knowledge of epiphytes and more nuanced explanations of their ecological importance:

“See, once I read a study and it said that the places where you can find a large number and diversity of epiphytic plants was synonymous with health, environmental health, forest health. So for me, I arrive at a place and look: ahh, you see mosses, you see lichens, you see this, you see that, then it is a healthy place. So, for me they have an indicator value when you are looking at the environment in your farm, in your community.”[Naturalistic Entrepreneur].

Seeing wildlife, especially birds, on their farms was cherished by many producers, and they connected wildlife visits with both trees and epiphytes. Among epiphytes, producers had observed animals drinking from bromeliad tanks, and they associated nectar for birds and insects with bromeliads and orchids. Trees also attracted more birds and animals to farms, which producers attributed to the food value of flowers and fruits and to the additional habitat structure trees offered. One producer told the story of wildlife returning to his farm after planting shade coffee:

“Birds of all kinds come, the trees have fruits then forest animals come, such as agoutis, pacas, birds of all kinds, because there’s an environment of trees that’s where the birds like to be. Before no, it was bare, it was grass, but now it’s not, now there’s a lot. There are birds, there are forest animals, it’s really beautiful how they’ve come. One day we saw a jaguarundi”(Coffee Reliant).

A few producers also felt strongly that having trees made their farms more beautiful and enjoyable to live in. As one noted simply, “A farm without water or trees to me isn’t a farm” (Coffee Reliant).

3.3. Motivations for Management Decisions

3.3.1. Economic Decisions

Producers universally discussed the low prices of coffee as problematic for their farms. Even large, financially stable farms felt that coffee might not continue to be a viable option long-term:

“The truth is that this [finances] is perhaps the most critical issue that people who work with coffee have, with the prices that we have, with the financial drag of the deficit that we have had in previous years, the climate that sometimes isn’t helping us, so we have had serious problems. I do not have bank financing, I try to do everything away from the banks because I have some fear of constraints, but people who work with credit today are enormously worried they are not covering their costs and they are definitely going to lose out on the exercise”(Naturalistic Entrepreneur).

One Naturalistic Entrepreneur stated that coffee production used to support the ecotourist lodge on her farm and now income from the lodge subsidizes coffee farming. A farm manager on a Large-scale Typical farm explained that, due to low prices, his farm had been slowly taking land out of coffee production and putting it into other land uses. Many of the producers who depended mainly on coffee stated that they had switched to growing coffee for economic reasons. Several also indicated that sustained low prices could cause them to shift to a different crop, suggesting that all farms in our study were to some degree governed by markets [23]. In previous coffee price declines, coffee abandonment, including switching to other land uses and leaving farming altogether, has been prevalent among smallholders [47]. Given the predicted decreases in yield and land suitability for coffee under climate change scenarios [27] combined with the already low prices identified by producers, it is reasonable to expect that coffee farming will become harder to maintain for farms of all sizes.

Economic status was self-perpetuating within all typologies and informed decision-making. Among Naturalistic Entrepreneurs and Large-Scale Typical producers, greater financial resources allowed investments in farm infrastructure and additions to the land base to boost future profits [22]. Several Naturalistic Entrepreneurs described plans to invest in processing equipment so that they could mill coffee on-site, increasing their profit margin. Conversely, Coffee Reliant producers were locked in a cycle of credit and debt, and credit constrained by the low total value of their harvest, inhibiting their ability to make long-term plans or investments. Farm diversification and off-farm work can enable greater financial independence and income smoothing to producers [3,21], and we saw some evidence of this among our respondents. One Off-Farm Income producer had just purchased a new parcel of land where he was planting coffee for the first time. Several Small Independent producers could avoid taking loans because a family member had a year-round income from permanent work. Provisioning services from trees can also buffer coffee producers against years of low yield or crop failure and help them to remain in coffee production over time [47]. The high importance of firewood for our respondents and the prevalence of fruiting trees on the farms indicates this may be the case in our study group as well.

The decision to initially add trees to farms may be inhibited by short-term economic calculations, especially for those experiencing the greatest economic hardship. When producers are unable to see the immediate economic value of adding trees, they may not be willing to make the investment of capital or labor, particularly when they would need to grow trees from seeds themselves. One producer explained that many farmers do not see the immediate economic benefit of adding trees:

“The thing is that the majority of producers, when we plant a coffee plant, we can see the dollars above it, but when we plant a tree, we don’t. We only focus on that, in the coffee there is the dollar sign”(Coffee and Cattle).

The majority of farmers in this study had received trees for free as part of the ABC project. Many indicated that they would like to receive more, and some shared that their neighbors had inquired about how to receive free trees. Once producers have a positive experience planting trees, they often wish to plant more [36,37], indicating that defraying the costs of tree planting may alone be incentive enough to increase tree cover on the landscape.

Although we hypothesized that labor shortages would be a major concern for coffee producers based on evidence from other coffee-growing regions [24], our data did not support that. Large farms tended to hire workers year-round and small farms depended on family labor [21], although some larger farms in the Coffee and Cattle and Coffee Reliant groups mainly relied on labor from a large extended family. Large farms had little trouble recruiting migrant laborers from other departments of the country for the harvest season, particularly when they treated workers well. Smallholders collaborated with their neighbors and extended family during the harvest to bring in the crop on multiple farms, demonstrating reciprocity [23]. In our interviews, labor was discussed as an economic constraint (not being able to pay laborers) rather than in relation to the availability, and producers sometimes limited labor-intensive activities such as tree pruning when finances were tight. Some smallholders may also substitute external inputs (e.g., chemical fertilizer) when they can afford to rather than using environmentally friendly but labor-intensive techniques such as composting organic fertilizer to avoid the drudgery of extra labor investments [23].

3.3.2. Knowledge-Based Decisions

There was a great discrepancy in the knowledge base among the producers we interviewed. Beyond differences in general education, there was a sizeable knowledge gap between the producers who had personal training in agronomy and those whose only access to agronomic expertise comes in the form of a credit assessor from a bank or cooperative who examines their crop once a year and makes suggestions. The Naturalistic Entrepreneurs, many of whom were college-educated with degrees in agronomy or business, were distinct from the rest of the groups in this respect. Their greater access to knowledge was accompanied by greater financial resources and may be related to generational wealth. They gathered data on their farms, including soil analysis and weather station measurements, which they combined with their agronomic education to implement more innovative farming practices. As one said of his farm, “This is a center for me to experiment” (Naturalistic Entrepreneur). Interviewees with greater agronomic expertise offered lengthy discussions of management improvements they had made on their farms in recent years. They also had plans for new innovations that could help them adapt to climate change, including changing the timing and intensity of shade tree pruning to leave more foliage in place during the hotter summer months and planting new varieties of coffee they believed to be more heat tolerant.

In other groups, producers were less likely to try new practices, although whether this was due to higher perceived risk or to lower access to agronomic expertise was unclear [22]. Many stated that they had not made changes in recent years, that they did not plan to modify their practices in relation to climate change, and that their management mirrored that of their neighbors. Many expressed a desire for more agronomic advice that could help them reach a level of sophistication in their farming that they witnessed on larger farms but currently considered unattainable. One Small Independent producer had previously taken part in an extension program to grow organic cabbage, but he had not applied any of the same practices to coffee production because he felt he needed someone with more agronomic expertise to assist him. A Coffee Reliant producer had implemented past suggestions from a credit assessor with good success and wished for more recommendations he could try. Several producers indicated that they also would like to know more about epiphytes after talking with us.

3.3.3. Values-Based Decisions

According to the classification system proposed by [46] to categorize human values for nature, aesthetic, naturalistic, utilitarian, and ecologistic-scientific values for conservation were high among the producers we interviewed. These values were expressed across typologies and interacted with economic pressures and access to agronomic expertise to influence decision-making. Naturalistic Entrepreneurs had high naturalistic and ecologistic-scientific values for biodiversity, including enjoyment of nature and appreciation for the ecological interactions occurring on their farms [46]. Those values informed management decisions because they had the financial means for their behaviors to align with their attitudes [39]. Some of their environmentally friendly practices, including vermicomposting of coffee waste, non-chemical insect control methods, and dyke systems for soil conservation, were more costly in terms of labor or capital or required specialized expertise to implement and were thus out of reach for other producer groups despite shared values.

Aesthetic and utilitarian values, including the appreciation for the beauty of nature and material benefit from the trees on their farms [46], were regularly expressed among producers in the other groups. These values informed some practices and were particularly apparent in the decision to grow shade coffee. One producer explained that his rationale for switching to growing coffee combined economics and values:

“[We switched to coffee] because we realized that it would sell for a little more, but also that it would protect the soil. Because the soil in the cornfield was eroding, but with the coffee it was protected”(Small Independent).

Although producers with higher levels of education or more access to agronomic expertise were better able to articulate ecological processes on their farms, producers across typologies expressed values for nature. These values informed management decisions when they were not overridden by economic constraints. For example, one producer explained his decision to preserve epiphytes based on aesthetic and naturalistic values:

“For me they are very beautiful plants, they give a great enhancement to the farm. People here don’t know them and they don’t know what is beautiful, so they destroy them and get rid of them. Not us, we take care of them. Those plants are being lost, they are numbered on the farms that you have. They grab them and cut them, but we don’t. You will see here on the farm how they are, and we plant them, we cultivate them. We like it like that, because my wife is a lover of plants, we all are”(Small Independent).

Producers attributed different ecosystem services to trees based on their values and financial stability. Those who rely on the provisioning services from trees tended to express their attitudes toward trees in terms of those that were best for firewood or timber. On the other hand, Naturalistic Entrepreneurs expressed their tree preferences in terms of regulating and cultural services, including improving soil and water or supporting wildlife. In actuality, however, those preferences did not translate into differences in tree species richness or composition among typologies. Most farms contained predominantly guaba (Inga spp.), a multifunctional tree appreciated variously by all typologies for firewood, ease of maintenance, nitrogen fixation, and wildlife conservation. Interspersed were smaller numbers of a wide variety of mostly native species, which many producers preferred for timber, but the Naturalistic Entrepreneurs associated with supporting wildlife.

4. Conclusions

The producers in our study identified many benefits and services from the trees on their farms, as well as some costs. They held fewer opinions about epiphytes, and their attitudes varied with the epiphyte group. Based on these responses, we note several tensions between producers’ management needs for coffee productivity and the conditions required for diverse epiphyte communities. Epiphytes are most diverse and abundant at the higher elevations of our study region [15,48], a fact that was noted by several respondents as well. While the higher humidity benefits epiphytes, producers in those zones manage shade trees more intensively to prevent American leaf spots. Thus, shade trees are pruned most aggressively in the areas that are most compatible with epiphyte conservation. Tree pruning damages epiphyte populations by regularly removing habitat substrate and killing individuals. The annual losses may structure the age and species composition of epiphyte populations within coffee farms, selecting against slower-growing species [49]. Producers were most likely to remove epiphytic bryophytes, particularly from their coffee plants. However, bryophyte cover is important to the establishment of the epiphytes producers appreciated, especially orchids [41,50], and repeated bryophyte removal may lower overall bryophyte cover, inhibiting vascular epiphytes from establishing. Despite these caveats, shade coffee systems still support considerable epiphyte populations and should be considered reservoirs for diversity, particularly in highly fragmented landscapes [12,13,19].

We found that financial stability, access to agronomic expertise, and personal values all informed the management decisions producers made. Farm size was a relatively good proxy for financial position, including debt and hired labor, and agronomic training, but measuring these variables explicitly allowed us to identify more nuanced typologies that captured decision calculus obscured by evaluating farm size alone. Based on these findings, we believe that economic-based and knowledge-based interventions should be employed, particularly when they can be integrated within the values producers already hold for nature. As producers and scientists alike have recognized, shade coffee is a better land use than most other forms of agriculture [1,5], so maintaining farms in shade coffee cultivation and adding trees to the farm landscape should be prioritized as key conservation outcomes.

Interventions aimed at improving livelihoods for producers can also have important conservation benefits. Foremost among these, programs providing shade trees at no cost to coffee producers can offer important provisioning and regulating services that buffer farmers against economic hardship while also improving the habitat availability for numerous species. Both our results and previous studies [36,37] indicate that producers are likely to plant trees when the trees are provided at low or no cost. Additionally, programs to coordinate enrollment in certification programs via cooperatives may be effective in maintaining livelihoods for producers, particularly those on small farms, in the face of price downturns [21,47]. However, certifications may be most compatible with larger farms already producing higher quality coffee. Several Naturalistic Entrepreneurs in our study currently benefit from Rainforest Alliance certification, and others expressed interest in certifications as a means to attain higher prices.

We also found that lack of access to agronomic expertise inhibited many producers from innovating their practices. This barrier is particularly acute in relation to climate change because farmers who cannot alter management practices to adapt to a warmer and more variable climate are unlikely to succeed with coffee farming in the future. Access to agronomic expertise can also drive innovation to improve coffee quality, permitting access to markets with higher price points, as evidenced by some of the Naturalistic Entrepreneurs we interviewed. Additionally, while dissemination of knowledge about epiphytes is needed to reduce epiphyte removal, the aesthetic appreciation for epiphytes [20] and the understanding of their importance to wildlife that we observed should facilitate behavioral change with a small amount of outreach effort.

Finally, interventions are most likely to succeed when they take into account producers’ values and local knowledge [6,35,39,40]. We documented strong values for nature among many of the producers we interviewed; in particular, their recognition of the restorative potential of shade coffee over other land-use practices. Building agronomic and financial capacity in ways that acknowledge producers’ values and understanding of ecological interactions can enhance farm resiliency and ensure continuity of coffee production over the long term. The ecosystem services provided to producers and the conservation benefits for wildlife will only continue to accrue.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su13137227/s1, Figure S1. Area of study. All farms in this study fell within the area of north-central Nicaragua outlined in red around the cities of Jinotega and Matagalpa. Base map courtesy of the Nations Online Project. Table S1. Shade tree species observed in ecological surveys. We report the total number of individuals observed in 87 survey plots and the percent of interviewees who mentioned the species. When uses and positive or negative attributes were mentioned in interviews, we have included those. Origin (native or exotic) was based on records in Flora de Nicaragua [51].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.R. and A.V.; methodology, J.H.R. and I.M.T.L.; software, J.H.R.; validation, J.H.R., formal analysis, J.H.R.; investigation, J.H.R. and I.M.T.L.; resources, J.H.R. and I.M.T.L.; data curation, J.H.R. and I.M.T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.R.; writing—review and editing, J.H.R. and A.V.; visualization, J.H.R.; supervision, A.V.; project administration, J.H.R.; funding acquisition, J.H.R. and A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Garden Club of America Award in Tropical Botany, a Nave Short-Term Research Grant, and a Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems Summer Mini-Grant awarded to J.H.R. J.H.R. was supported by the Dickie Family Sauk County Educational Award, the Graduate School and the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Education and Social/Behavioral Science Institutional Review Board (protocol code 2018-0174, 19 March 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Quantitative data used in this paper are available at https://osf.io/jgd73/, accessed on 11 June 2021. Original interview transcripts with identifying information redacted are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nicaraguan farmers who graciously took the time to participate in our research. Thank you to A. Rothman at the American Bird Conservancy for providing access to the list of farms that participated in their project. We are grateful to P. Robbins for consultation at multiple stages of the research and to E. Damschen and three anonymous reviewers for critical comments that improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Interview questions and topics

Closed-ended Questions

How many hectares of land do you own?

How many hectares are in coffee?

What other crops/farm products do you produce?

Which crops/farm products do you sell and which are for your own use?

How many years have you owned the farm?

How many types of trees do you have on your farm (within the coffee)?

Do you use chemicals like fungicides or pesticides on coffee? For what purposes?

Are you a member of a cooperative?

Do you receive technical assistance?

How many people work on your farm?

Do you hire any laborers outside your family? How many?

Do members of your family work off farm? Who? What jobs? What parts of the year?

What portion of your household income is from coffee?

Open-ended interview topics

Financial (in)security and debt

Comparison with other neighboring farms

Annual management cycle

Process of decision-making on farm

Perceptions of climate change and responses in farm management

Recent management changes on the farm and why

Uses/benefits of trees (including any disadvantages)

Uses/benefits of epiphytes (including any disadvantages)

Appendix B

Quotations used in original Spanish with English translations

Original: La frescura de la planta, hasta donde manejo, si un grano dura más en llegar a la maduración recoge más nutrientes, hay un mejor sabor en la taza, mientras que si está expuesto al sol se estresa más y tira todas sus energías al grano y madura más rápido, en el caso de la calidad de la taza creo que no es bueno

Translation: If the bean takes longer to mature, it picks up more nutrients and it has a better taste in the cup, while if it is exposed to the sun, it is stressed more and throws all its energy to the bean, which matures faster and, in the case of the quality of the cup, I think it’s not good.

Original: Es que hay que darle un manejo también, no es que los va a sembrar en el café y los va a dejar que se hagan…bueno, se le hace algún manejo para que puedan vivir los dos ahí, porque los necesitamos los árboles y también necesitamos el café

Translation: The thing is you have to manage them [trees], you can’t just plant them in the coffee and let them do whatever they will… so you do some management so that they both can live there, because we need the trees and we also need the coffee.

Original: Los árboles en cafetales nos sirven para mantener una temperatura más homogénea dentro de la plantación … yo soy asesor de cultivos de café y voy a muchas plantaciones de café … y siempre vemos mejor amortiguar mejor los cambios, la variabilidad climática cuando tenemos una cantidad de árboles en el café, eso es, eso es indudable.

Translation: The trees in coffee plantations help us to maintain a more homogeneous temperature within the plantation … I am a coffee crop consultant and I go to many coffee plantations … and we always see that it cushions the changes better, the climatic variability, when we have a number of trees in the coffee. That is undeniable.

Original: Cuando hay una planta de musgo que enraíza mucho, entonces a la planta productora y de tallo débil lo oprime demasiado, y entonces llama a debilitarle el follaje, en el caso del café, entonces y la humedad que produce, lo hace que le produzca hongo y comienza hacerle daño, por eso es que todo debe ser controlado.

Translation: When there is moss that takes root all over, it squeezes the producing plant too much and weakens the stem, and then it weakens the foliage, in the case of coffee. And then the humidity it produces, that produces fungus and it begins to do damage, that’s why everything must be controlled.

Original: Pues vea, yo creo que si lo pensamos con calma, el café es un cultivo, un cultivo muy noble y entre tener 50 manzanas de pasto y tener 50 manzanas de café, yo creo que debemos tener 50 manzanas de café, porque tenemos 50 manzanas de árboles, en 50 manzanas de árboles hay 200,000 árboles que producen una cantidad increíble de lámina foliar, que transpira, que respira, que purifica, que da mejor vida, que retiene más humedad en el suelo, entonces hoy por hoy podemos ver si estos lugares que la finca tenía muy áridos, que cuando los convertimos a cafetales y les pusimos sombra porque soy amante a esa sombra, este han cambiado enormemente, ya se miran los suelos diferentes … de hecho, de hecho, si no tuviera, yo no sé la gente que piense que debe haber árboles, estamos jodidos, yo estoy reforestando las quebradas, estoy reforestando los ojos de agua, los ríos, haciendo cercas vivas, nosotros solo el año pasado pusimos 2000 árboles en una finca pequeña como esta y hacemos todo lo que podemos tratando de que eso funcione

Translation: Okay, look, I think if we think about it calmly, coffee is a crop, a very noble crop and between having 50 manzanas of pasture and having 50 manzanas of coffee, I think we should have 50 manzanas of coffee, because we have 50 manzanas of trees. In 50 manzanas of trees there are 200,000 trees that produce an incredible amount of leaf area, that transpire, that respire, that purify, that give better life, that retain more moisture in the soil. So, day by day, we can see these places where the farm was really arid, that when we converted them to coffee plantations and we put them in shade—because I am in love with that shade—it has changed enormously, you can already see the differences in the soil. In fact, in fact, if we didn’t have… I don’t know… the people who think there should be trees, we’d be screwed. I’m reforesting the creeks, I’m reforesting the water sources, the rivers, making living fences. Just last year, we put 2000 trees into a small farm like this one last year and we are doing all we can to try to make that work.

Original: esa parte no se podía pegar café ahí, por lo que la tierra había quedado lavada de viaje, quedo una mera capita de tierra fértil, entonces a medida que se fue sembrando arboles la tierra se ha ido componiendo con la hoja que cae y la rama que se pudre todo eso ahí

Translation: you couldn’t plant coffee here, the earth had been washed away, it had just a thin sheet of fertile soil, but as trees were planted new soil has been forming with the leaves that fall and the branches that rot adding to it.

Original: ahí había un ojo de agua antes y no había madera y yo le sembré madera y volvió ese ojo de agua, volvió a revertirse y mejor con la madera, ya lo tengo experimentado en dos fuentes de agua que hay ahí … cuando yo compre ahí, los muchachos anteriores tenían verduras ahí, lo habían despalado de viaje, de viaje totalmente y yo le sembré café y la siembra de madera que hay ahí volvieron esos ojos de agua y volvieron hasta más opulentos.

Translation: There was a spring before but there were no trees and I planted trees and that spring came back, it reverted and better than before! With trees, I have now experienced it with two springs that are here … when I bought that [parcel], the previous guys had vegetables there, the soil was running away, and I planted coffee and the trees that are there and those springs returned and they returned even more opulent. The trees are helpful for life and for many things, for all of humanity, it could be said.

Original: vea, en una ocasión leía un estudio y decía que los lugares donde puede encontrar un sin número y diversidad de plantas epifitas era sinónimo de salud, salud del ambiente, salud del bosque, entonces para mí yo llego a un lugar y miro, ahh, se miran musgos, se miran líquenes, se miran esto, se mira lo otro, entonces es un lugar sano, entonces para mi tienen el valor del indicativo adonde estas llevando el medio ambiente en tu finca, en tu comunidad

Translation: See, once I read a study and it said that the places where you can find a large number and diversity of epiphytic plants was synonymous with health, environmental health, forest health. So for me, I arrive at a place and look: ahh, you see mosses, you see lichens, you see this, you see that, then it is a healthy place. So, for me they have an indicator value when you are looking at the environment in your farm, in your community.

Original: ahora vienen aves de todo tipo. si, vienen aves de todo tipo, también este, como están los árboles, están las frutas entonces vienen animales del monte, como guatusas, guardiolas, aves de todo tipo, porque hay un entorno de árboles que es donde las aves les gusta estar. ya, antes no, era pelado, era zacate, ahora no, ahora hay bastante, bastante, aves, hay, hay animales de monte, bastante, bastante, bonito es, han venido, un día de estos miramos un leoncillo.

Translation: Birds of all kinds come, the trees have fruits then forest animals come, such as agoutis, pacas, birds of all kinds, because there’s an environment of trees that’s where the birds like to be. Before no, it was bare, it was grass, but now it’s not, now there’s a lot. There are birds, there are forest animals, it’s really beautiful how they’ve come. One day we saw a jaguarundi.

Original: Una finca que no tenga agua y árboles para mí no es finca.

Translation: A farm without water or trees to me isn’t a farm.

Original: La verdad es que ese es el tema más tal vez más álgido que tenemos la gente que trabajamos con café, con los precios que tenemos, con el arrastre financiero deficitario que hemos tenido los años anteriores, el clima que a veces no nos está ayudando, entonces hemos tenido problemas serios, yo no tengo financiamiento bancario, todo trato de hacerlo de la manera, lejos de los bancos porque tengo cierto miedo y restricciones, pero la gente que trabaja con crédito, hoy por hoy está enormemente preocupada, no están cubriendo sus costos y definitivamente van a perder en el ejercicio

Translation: The truth is that this [finances] is the most perhaps most critical issue that people who work with coffee have, with the prices that we have, with the financial drag of the deficit that we have had in previous years, the climate that sometimes isn’t helping us, so we have had serious problems. I do not have bank financing, I try to do everything away from the banks because I have some fear of constraints, but people who work with credit today are enormously worried they are not covering their costs and they are definitely going to lose out on the exercise.

Original: Es que la mayoría de los productores, cuando nosotros sembramos un árbol de café, arriba le vemos los dólares ya, pero si sembramos un árbol no, solo nos enfocamos en eso, en el café, en el signo de córdoba o de dólar.

Translation: The thing is that the majority of producers, when we plant a coffee plant, we can see the dollars above it, but when we plant a tree, we don’t. We only focus on that, in the coffee there is the dollar sign.

Original: …porque sacamos la cuenta que daba un poquito más el café, además que se protege el suelo, porque en el caso de la huerta la estábamos erosionando, con el café se protege

Translation: [We switched to coffee] because we realized that it would sell for a little more, but also that it would protect the soil. Because the soil in the cornfield was eroding, but with the coffee it was protected.

Original: Para mi es una planta muy bonita, te le da un gran realce a la finca, la gente aquí como no las conoce y como no sabe lo que es bonito, aquí más bien las destruye la gente, las bota, nosotros no, nosotros las cuidamos, esas plantas se van perdiendo, son contadas en las fincas que vos hayas esas plantas, las agarran, las machetean y nosotros no, ahí vas a ver aquí en la finca como están y sembramos, las cultivamos, nos gusta pues, porque mi esposa es amante de las plantas, todos lo somos

Translation: For me they are very beautiful plants, they give a great enhancement to the farm. People here don’t know them and they don’t know what is beautiful, so they destroy them and get rid of them. Not us, we take care of them. Those plants are being lost, they are numbered on the farms that you have. They grab them and cut them, but we don’t. You will see here on the farm how they are and we plant them, we cultivate them. We like it like that, because my wife is a lover of plants, we all are.

References

- De Beenhouwer, M.; Aerts, R.; Honnay, O. A Global Meta-Analysis of the Biodiversity and Ecosystem Service Benefits of Coffee and Cacao Agroforestry. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 175, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfecto, I.; Vandermeer, J. Coffee Agroecology; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, S.M. Coffee agroforestry in the aftermath of modernization: Diversified production and livelihood strategies in post-reform Nicaragua. In Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Fair Trade, Sustainable Livelihoods and Ecosystems in Mexico and Central America; Bacon, C.M., Méndez, V.E., Gliessman, S.R., Goodman, D., Fox, J.A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 179–206. [Google Scholar]

- Tscharntke, T.; Clough, Y.; Bhagwat, S.A.; Buchori, D.; Faust, H.; Hertel, D.; Hölscher, D.; Juhrbandt, J.; Kessler, M.; Perfecto, I.; et al. Multifunctional Shade-Tree Management in Tropical Agroforestry Landscapes—A Review. J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jha, S.; Bacon, C.M.; Philpott, S.M.; Méndez, V.E.; Laderach, P.; Rice, R.A. Shade Coffee: Update on a Disappearing Refuge for Biodiversity. BioScience 2014, 64, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toledo, V.M.; Moguel, P. Coffee and Sustainability: The Multiple Values of Traditional Shaded Coffee. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Angón, A.; Greenberg, R. Are Epiphytes Important for Birds in Coffee Plantations? An Experimental Assessment. J. Appl. Ecol. 2005, 42, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanth, K.K.; Sankararaman, V.; Dalvi, S.; Srivathsa, A.; Parameshwaran, R.; Sharma, S.; Robbins, P.; Chhatre, A. Producing Diversity: Agroforests Sustain Avian Richness and Abundance in India’s Western Ghats. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 4, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mas, A.H.; Dietsch, T.V. Linking Shade Coffee Certification to Biodiversity Conservation: Butterflies and Birds in Chiapas, Mexico. Ecol. Appl. 2004, 14, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Häger, A.; Otárola, M.F.; Stuhlmacher, M.F.; Castillo, R.A.; Arias, A.C. Effects of Management and Landscape Composition on the Diversity and Structure of Tree Species Assemblages in Coffee Agroforests. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 199, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggar, J.; Asigbaase, M.; Bonilla, G.; Pico, J.; Quilo, A. Tree Diversity on Sustainably Certified and Conventional Coffee Farms in Central America. Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 24, 1175–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hietz, P. Conservation of Vascular Epiphyte Diversity in Mexican Coffee Plantations. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, K.E.; Bacon, C.M.; Mendez, V.E. Shade Tree Diversity, Carbon Sequestration, and Epiphyte Presence in Coffee Agroecosystems: A Decade of Smallholder Management in San Ramón, Nicaragua. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 199, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.H.; Torrez Luna, I.M.; Waller, D.M. Tree Longevity Drives Conservation Value of Shade Coffee Farms for Vascular Epiphytes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 301, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, A.H.; Dodson, C.H. Diversity and Biogeography of Neotropical Vascular Epiphytes. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 1987, 74, 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Köster, N.; Friedrich, K.; Nieder, J.; Barthlott, W. Conservation of Epiphyte Diversity in an Andean Landscape Transformed by Human Land Use. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einzmann, H.J.R.; Zotz, G. How Diverse Are Epiphyte Assemblages in Plantations and Secondary Forests in Tropical Lowlands? Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2016, 9, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toledo-Aceves, T.; Mehltreter, K.; García-Franco, J.G.; Hernández-Rojas, A.; Sosa, V.J. Benefits and Costs of Epiphyte Management in Shade Coffee Plantations. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 181, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Montero, L.; Quintana-Palacios, V.; Damon, A. Impact of Moss and Epiphyte Removal on Coffee Production and Implications for Epiphyte Conservation in Shade Coffee Plantations in Southeast Mexico. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 43, 1124–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, V.E.; Bacon, C.M.; Olson, M.; Morris, K.S.; Shattuck, A. Agrobiodiversity and Shade Coffee Smallholder Livelihoods: A Review and Synthesis of Ten Years of Research in Central America. Prof. Geogr. 2010, 62, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.M. Confronting the coffee crisis: Can Fair Trade, organic, and specialty coffee reduce the vulnerability of small-scale farmers in northern Nicaragua. In Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Fair Trade, Sustainable Livelihoods and Ecosystems in Mexico and Central America; Bacon, C.M., Méndez, V.E., Gliessman, S.R., Goodman, D., Fox, J.A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Guadarrama-Zugasti, C. A grower typology approach to assessing the environmental impact of coffee farming in Veracruz, Mexico. In Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Fair Trade, Sustainable Livelihoods and Ecosystems in Mexico and Central America; Bacon, C.M., Méndez, V.E., Gliessman, S.R., Goodman, D., Fox, J.A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. The New Peasantries: Struggles for Autonomy and Sustainability in an Era of Empire and Globalization; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, P.; Tripuraneni, V.; Karanth, K.K.; Chhatre, A. Coffee, Trees, and Labor: Political Economy of Biodiversity in Commodity Agroforests. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.M.; Sundstrom, W.A.; Flores Gómez, M.E.; Méndez, V.E.; Santos, R.; Goldoftas, B.; Dougherty, I. Explaining the ‘Hungry Farmer Paradox’: Smallholders and Fair Trade Cooperatives Navigate Seasonality and Change in Nicaragua’s Corn and Coffee Markets. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 25, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.M.; Sundstrom, W.A.; Stewart, I.T.; Beezer, D. Vulnerability to Cumulative Hazards: Coping with the Coffee Leaf Rust Outbreak, Drought, and Food Insecurity in Nicaragua. World Dev. 2017, 93, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, C.; Läderach, P.; Rivera, O.O.; Kirschke, D. A Bitter Cup: Climate Change Profile of Global Production of Arabica and Robusta Coffee. Clim. Chang. 2015, 129, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beer, J. Advantages, Disadvantages and Desirable Characteristics of Shade Trees for Coffee, Cacao and Tea. Agrofor. Syst. 1987, 5, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles, P.; Harmand, J.-M.; Vaast, P. Effects of Inga Densiflora on the Microclimate of Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) and Overall Biomass under Optimal Growing Conditions in Costa Rica. Agrofor. Syst. 2010, 78, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oijen, M.; Dauzat, J.; Harmand, J.-M.; Lawson, G.; Vaast, P. Coffee Agroforestry Systems in Central America: II. Development of a Simple Process-Based Model and Preliminary Results. Agrofor. Syst. 2010, 80, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Pinto, L.; Perfecto, I.; Castillo-Hernandez, J.; Caballero-Nieto, J. Shade Effect on Coffee Production at the Northern Tzeltal Zone of the State of Chiapas, Mexico. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 80, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrach, A.; Laurance, W.F.; Larrinaga, A.R.; Santamaria, L. Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Forest Fragmentation on Interspecific Interactions. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 1342–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rice, R.A. Agricultural Intensification within Agroforestry: The Case of Coffee and Wood Products. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 128, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Rigal, C.; Liebig, T.; Mremi, R.; Hemp, A.; Jones, M.; Price, E.; Preziosi, R. Ecosystem Services and Importance of Common Tree Species in Coffee-Agroforestry Systems: Local Knowledge of Small-Scale Farmers at Mt. Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Forests 2019, 10, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerdán, C.R.; Rebolledo, M.C.; Soto, G.; Rapidel, B.; Sinclair, F.L. Local Knowledge of Impacts of Tree Cover on Ecosystem Services in Smallholder Coffee Production Systems. Agric. Syst. 2012, 110, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garen, E.J.; Saltonstall, K.; Slusser, J.L.; Mathias, S.; Ashton, M.S.; Hall, J.S. An Evaluation of Farmers’ Experiences Planting Native Trees in Rural Panama: Implications for Reforestation with Native Species in Agricultural Landscapes. Agrofor. Syst. 2009, 76, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertin, A.; Nair, P.K.R. Farmers’ Perspectives on the Role of Shade Trees in Coffee Production Systems: An Assessment from the Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica. Hum. Ecol. 2004, 32, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, P.; Chhatre, A.; Karanth, K. Political Ecology of Commodity Agroforests and Tropical Biodiversity: Commodity Agroforest Biodiversity. Conserv. Lett. 2015, 8, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberlein, T.A. Environmental Attitudes; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-19-977333-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N.A.; Shaw, S.; Ross, H.; Witt, K.; Pinner, B. The Study of Human Values in Understanding and Managing Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richards, J.H. Assessing the Strength of Climate and Land-use Influences on Montane Epiphyte Communities. Conserv. Biol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté, E.; Legendre, P.; Shipley, B. FD: Measuring Functional Diversity (FD) from Multiple Traits, and Other Tools for Functional Ecology. 2014. Available online: https://mran.microsoft.com/snapshot/2014-11-17/web/packages/FD/FD.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Valencia, V.; West, P.; Sterling, E.J.; García-Barrios, L.; Naeem, S. The Use of Farmers’ Knowledge in Coffee Agroforestry Management: Implications for the Conservation of Tree Biodiversity. Ecosphere 2015, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamond, G.; Sandbrook, L.; Gassner, A.; Sinclair, F.L. Local Knowledge of Tree Attributes Underpins Species Selection on Coffee Farms. Exp. Agric. 2019, 55, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kellert, S.R. The Value of Life: Biological Diversity and Human Society; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]