1. Introduction

Over the years, the concept of landscape has explored the man–nature, built–environment bond as both dimensions are necessary for the protection and life of a portion of territory [

1]. This perspective has led to the overcoming of an aesthetic, photographic vision of the landscape towards a dynamic and multi-level vision in which the multi-disciplinary analyses that investigate the interaction between environmental and cultural aspects take on great interest, both economic and social, on which the evolution and conservation of a territorial context depend [

1,

2].

In recent years, landscape culture has grown, and various disciplines have made significant, albeit separate, contributions [

3]. However, the Historical Urban Landscape (HUL) approach aspires to a more general and operational concept that aims to preserve the qualities of the landscape, improving the productive and sustainable use of resources of a territory, and to develop tools capable of improving the active role of a community in the management and planning of landscape resources [

4]. From this point of view, landscape and social innovation are an inseparable pair; the most recent orientations look, on the one hand, towards local development as a key theme of innovation, and, on the other, to social innovation as ‘groundbreaking innovation’ that can start a new cycle for the management of common goods, in which for-profit and non-profit subjects take on a leading role in public administration [

5,

6].

Today, territorial innovation, no longer ‘market-driven’, is linked to social innovation, typical of contexts in which there are interactions between places, people, and ideas.

A regenerative landscape model, therefore, starts from the recognition of marginal areas, unmet needs, and the actions implemented by civil society to improve the quality of life of their citizens, thus investigating the possibilities of developing intelligent and cooperative management systems that are capable of putting a value on local resources. In this way, a smart approach to the landscape is outlined, with a strong propensity for innovation in local governance aimed at experimenting with the role of civil society in the management of common goods [

7].

Therefore, HUL research aspires to provide dynamic tools that are able to adapt to different contexts, define actions based on shared value judgments that are really able to initiate processes of enhancement of the material and immaterial culture of a place without compromising its identity values [

8]. The thesis analyzes and experiments with a research approach that allows users/inhabitants to participate in the development and experimentation of innovative solutions aimed at a specific territory. Starting from the Living Lab approach, the intention is to integrate the evaluation processes into the development policies of a territory, identifying a network of participating and potentially interested local actors [

9,

10] with which to experiment new ways of managing landscape resources. The goal is to intercept and trigger local mechanisms capable of encouraging the development of design creativity in real-life sectors where civil society requires innovation. The aim is to ‘leaven’ endogenous development based on mutual knowledge and learning [

11]. These collaborative environments thus represent new systems of production of values in which the landscape is a living space rather than a physical one, and local action represents an impulse factor to improve and push governance actions towards models of cooperative self-governance of common goods [

12,

13].

Research in this field underlines the need for evaluative approaches based on complex adaptive systems, namely, systems focused on the response (adaptation) to different types of feedback. Exploring a broad decision-making context, it can be seen that the values of the resources and those of the subjects involved (direct, indirect, potential, future generations) are interdependent and interconnected from the perspective of Complex Social Values (CSVs) [

2,

14,

15]. The relationship between knowledge, values, and strategies is, therefore, fluid, dynamic, and incremental and requires continuous interaction between and with local actors and decision-makers [

16]. This relationship develops progressively through continuous feedback cycles that contribute to the development of mutual learning mechanisms. The recognition of local identity and cultural values is, therefore, the first step to stimulate the ability to initiate processes of innovation that involve historical and cultural heritage [

17].

Starting from a multi-disciplinary background, the research proposes the use and experimentation of adaptive and synergistic evaluations as tools for recognizing the CSV of the landscape and experimenting with new ways to promote and manage resources, with the intention to establish partnership relationships between local actors and develop models for the construction of choices and cooperative management [

18,

19,

20].

The methodology is configured as an experiment, linked to specific ‘places of value’ [

18] and personal relationships, where we try to trace the values and meanings of attractive places to build new tourist routes that reflect the concept of wellbeing, as perceived by a community, from the representation of the qualities of the landscape perceived by users [

21].

The trials were conducted and tested in Sila National Park (SNP) in Southern Italy to define strategies for the enhancement of local resources and generate a cooperative and collaborative network between all the municipalities of the SNP.

The methodology uses the Living Lab (LL) approach to investigate the conditions that stimulate territorial co-creativity towards regenerative models [

9,

22].

In the application of this approach, the integration of evaluation methods and tools to detect the local meanings of categories of universal value has been tested. The dynamic approach of the Cultural Values model represents the guide with which the information has been classified [

23]. Starting from the mapping of the physical characteristics and meanings attributed to places, a series of analyses (frequency, preference, network) that made it possible to investigate values in a relational and multi-dimensional dimension were developed. The role and type of relationship that contribute to the formation of values were investigated, starting from the perceptions of outsiders and insiders’ points of view, thus also exploring the lesser-known aspects and potentialities that emerge in the comparison between specific groups of users and citizens. The subsequent representation of the landscape thus becomes a moment of learning, awareness, and planning of possible actions.

The representations of new landscape maps that describe the affective paths through an archive of images and stories that represent the places where personal values and relationships are concentrated as the expression of the intrinsic value of a community, thus, give back the possibility of living a landscape experience in the SNP by discovering the dynamics that characterize it [

15].

In this way, the landscape is returned as a lived and potential experience capable of interpreting the physical qualities of the territory with regard to the meaning attributed by certain individuals.

The main result of the research is the identification of the ‘places of value’ and new tourist routes to promote and enhance the SNP. Through the qualities perceived by specific users and citizens, linked to the values of local resources and their emotional relationships with the territory, new tourist itineraries that reflect the concept of wellbeing, as perceived by the SNP community, are drawn. From this perspective, the SNP landscape is reconstructed, starting from a ‘new affective geography’ derived from the experiences and perceptions of the SNP community.

Information on spatial representation and landscape modeling helps us to understand tangible and intangible features, make more informed decisions, improve communication between stakeholders, and build shared common ground to react to critical situations and identify opportunities for improvement and adaptive promotion.

2. Circular Economy and Living Lab

Starting from a multi-disciplinary background, the research developed within territorial Living Labs proposes the use and experimentation of adaptive and synergistic evaluations as tools for recognizing the complex social value (CSV) of the landscape and experimenting with new ways of promoting and managing local resources [

10,

18,

19]. Through the experiment conducted within the Sila Labscape research project, a methodology was developed to investigate the conditions that stimulate territorial co-creativity towards regenerative models [

8].

These models refer to the capabilities of natural systems of self-regeneration of resources, in which the interactions between systems do not generate waste/scraps/impoverishment of values (as in linear models) but put matter and energy back into circulation. A regenerative landscape model, therefore, starts from the recognition of marginal areas, unmet needs, and actions implemented by civil society to improve the quality of life of their citizens, thus investigating the possibilities of developing intelligent and cooperative management systems that are capable of putting a value on local resources.

In the Sila Labscape, the potential of dialogic/communicative processes is investigated in order to build environments conducive to innovation, where exchanges between heterogeneous actors (multi-stakeholder environments), who have common objectives, can activate processes in which everyone can contribute to change. The Sila Labscape Living Lab, therefore, places human processes at the center of interpreting the landscape and builds the 4Ps (public, private, people partnerships) for the development of solutions linked to a specific context.

Within the LL, activated in the territory of the SNP, the integration of evaluation processes with the development policies of the territory by identifying a network of participating local actors potentially interested in experimenting and sharing new ways of managing the landscape resources of the SNP was intended [

9,

10].

LLs represent a valid tool for the development of processes of circularization [

16] of resources and skills, through which not only productive and organizational models change but also the behavior of consumers and citizens towards collaborative modalities [

19].

Circular processes [

20] require significant exchanges of information between several economic subjects and the ability to innovate not only the products but the entire production process [

24]. These models require highly developed organizational systems and, at the same time, push for cultural changes and more collaborative forms of economy.

At the local scale, a circular model of landscape resource regeneration can, therefore, contribute to the reconstruction of local economies. In small towns and in the innermost territories, where depopulation and human dynamics affect the quality of the landscape but elements of vitality persist (consolidated production traditions, one-to-one relationships, small scale, strong sense of identity, memory collective, possibility of easily interacting with the nearest local authorities), regenerative models of resources inspired by circular economic systems, such as slow tourism, can be applied with greater ease.

In this context, the research project aims to integrate the Living Labs approach in the process of enhancing the landscape of the SNP [

25,

26,

27].

LLs are, in fact, collaborative environments of open innovation [

11] in which the active involvement of end-users makes it possible to create paths for the co-creation of new services, products, and social infrastructures by activating partnerships of public–private–people (4P) [

12,

27].

The LL approach to the territory then allows us to explore, co-design, and test new services or resource management methods towards an integrated development model. The specific needs of defined user groups are put at the center, and an environment conducive to experimentation is built, that is, made up of people who are actually interested and willing to collaborate for the reconstruction and development of the local economy.

The whole process makes it possible to identify and strengthen the relationships between the parties involved (public/private/people) [

27]. The phases of consultation, negotiation, involvement, collaboration allow us to experiment with new forms of responsibility and interaction, allowing, at the same time, the innovation of strategies or methods of governance. The process is therefore configured as a path of mutual maturation and learning between the participants, who also co-design with the experts the preparatory actions or activities for the implementation of innovation.

Furthermore, the operational framework, integrated with Multicriteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) as a decision support system, helps Decision-Makers (DMs) to make strategic decisions efficiently and define concrete solutions [

25] through monitoring the management and evaluation of landscape resources in multi-dimensional contexts [

28,

29].

Over the past three decades, Spatial Decision Support Systems (SDSS), combining MCDA and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), have improved the assessment and interaction between local stakeholders and the design of new sustainable scenarios [

30,

31,

32]. Many of these tools (geo-information technology-based instruments) are increasingly used to support planners and decision-makers in developing planning support systems (PSS) and visually attractive and interactive platforms. In planning processes, it is possible to include and manage explicit and codified information, structure the mutual exchange of knowledge between heterogeneous groups of actors, support participatory processes and collaborative deliberations, simulate the consequences of planning, and collect public contributions to improve local planning practices and inclusion [

33,

34].

As mentioned, the methodology was tested on the SNP case study (

Section 2). Along with a brief description of the focus area, the methodology and results deriving from the application are described in the following paragraphs.

According to the Living Lab approach, building partnerships between institutions, associations representing civil society, and citizens certainly improves the reliability of the decision-making process aimed at identifying sustainable promotional strategies for the enhancement of resilient landscapes.

The experimental research applied to the case study, starting from the research of the identity factors of the landscape, puts in place a multi-dimensional evaluation process that can also be used in other contexts to trace new tourist routes for an alternative model of promotion of the park’s resources, also useful for elaborating newly situated policies and bottom-up site-specific actions [

35,

36,

37,

38].

3. Case Study

The structuring of an interpretative and evaluative model has been implemented in the cultural landscape of Sila National Park (SNP) in Southern Italy (

Figure 1).

Sila National Park (SNP) is a site included in the World Network of UNESCO Sites of Excellence. It houses one of the richest systems of biodiversity, with a rich heritage of unique geological qualities and varieties. The park extends over a large and heterogeneous territory, consisting mainly of mountainous areas that attract many tourists, especially in the summer. It also includes inland areas that are sparsely populated; these are the areas that seek to leverage their cultural and environmental heritage to promote their land and, thus, reverse the phenomenon of depopulation [

2,

8,

11].

The SNP extends over an area of approximately 73,695 hectares, encompassing 21 municipalities in the provinces of Cosenza, Catanzaro, and Crotone, and is divided into three different areas: Sila Greca (north), Sila Grande (center), and Sila Piccola (south). The park was established in 2002 after a long legislative process that began in 1923 when, in Italy, people began to talk about protecting natural areas by establishing the first national parks. It includes most of the territories that were already part of the historic National Park of Calabria, established in 1968.

Inside the park, there are three of the six artificial basins present on the Sila plateau, which has a very large, wooded area, so much so that among the Italian national parks, it is the one with the greatest percentage of forests, about 80% of the total [

36]. Many valleys are open along the ridges of the park, where livestock farming is practiced, with forms of transhumance and pastures that still persist today; additionally, agriculture is linked, above all, to the cultivation of the Sila potato (IGP).

The International Coordination Council of the MAB Program (Man and the Biosphere Program), during its 26th session in Jönköping in Sweden, approved the registration of Sila as the 10th Italian Biosphere Reserve in the UNESCO World Network of Sites of Excellence.

Currently, the protected area of the park is a candidate to be included in the world list of UNESCO Global Parks.

It must be said that Sila National Park not only includes a vast territory rich in naturalistic and landscape beauty but also contains within it a concentrate of typical flavors, aromas, and high-quality knowledge that absolutely deserves to be experienced and savored through experiential tourism routes.

4. Materials and Methods

As already announced in the introduction, in the SNP, various laboratories were activated following the Living Lab approach [

34].

In particular, the decision analysis based on a spatial decision support system (SDSS) for a multi-functional landscape aims to help local actors and users to understand the local resources and multi-functional values of the SNP and the municipalities in neighboring areas and stimulate their collaboration in the management of environmental and cultural sites and the design of new enhancement strategies.

The methodological approach is structured in four phases—(i) Intelligence, (ii) Design, (iii) Choice, and (iv) Outcome—in order to take into account the needs of the community and implement widely shared enhancement strategies [

38]. For the elaboration of each phase, some evaluation methods that are suitable for representing and managing the complexity of the interests and objectives at stake were chosen, stimulating territorial co-creativity towards regenerative models [

22].

Following the Cultural Values Model (CVM) [

23], the Intelligence phase was marked by focus groups and in-depth interviews, with a specific group of people, insiders, and outsiders who had the same interest in the landscape and its heritage and were interested in working together to achieve shared objectives. The insiders were those who live and work on the territories of the park. The outsiders were external visitors, usually tourists or scholars.

According to the CVM [

35], the cultural values of the landscape are the foundation of the identity of the local community as the result of its relationship with the environment they have inhabited and changed over time [

23]. To determine which values are shared by the users of the landscape and to decipher the meanings of the places perceived as most significant, studies and surveys aimed at the perception of the landscape by specific groups of people and their expectations were conducted.

This allows us to recognize the general predisposition of users towards the choice of a certain type of landscape, the reasons for the choice, the importance of the experience, and the main positive or negative factors related to the personal perception of the landscape [

23,

26,

39,

40].

In particular, the studies on the perception of the landscape of the SNP examined the personal experience of certain groups of people and their expectations of the landscape of the park, recognizing the general disposition of users towards the studied landscape: why it is important to live land-scape of the park, what led them to live it, the key factors and the positive or negative characteristics related to their personal perception of the park landscape [

23,

26,

39,

40].

To define these meanings, the CVM [

35,

38] chooses an open and in-depth survey, which is aimed at a sample of dominant figures [

39] from the community of the analyzed landscape and people from different places [

23,

41,

42].

The main result of the survey is aimed at identifying the places in the territory and understanding the characteristics that determine their value for the inhabitants and for those who frequent the territory, even temporarily.

Therefore, starting from the paths suggested by people, it is possible to analyze human behavior by exploring the territory and attributing values to a stratified reality, such as the landscape [

43,

44].

4.1. Intelligence Phase. Investigation Tools: Interviews and Questionnaires

In the Intelligence phase, survey tools such as interviews and questionnaires were used to identify the places in the territory and to understand the characteristics that determine their values for the inhabitants and for those who frequent it, even temporarily.

An approach to the landscape was, therefore, experimented with, according to the indications of the European Convention, by stimulating people to express the vision of the environment in which they live and structuring methods and tools to detect this type of information.

Reasoning by values implies the exploration and search for ways to detect subjective fields; the value of a place may not necessarily be attributed to objective requirements (site, heritage, humanity) but can depend on subjective parameters (ability to contribute to meaning and the need for community).

Following the approach of the CVM, there are two main categories of actors linked to the landscape: the insiders who live, work, or have their roots in a given context and, therefore, express an internal point of view, namely, the fruit of collective knowledge; and outsiders who are external visitors, usually tourists or experts [

23].

For each category of actors, the processing of the soft data contained in the interviews makes it possible to highlight recurring semantic fields and detect the frequency of keywords associated with each main semantic field. [

45,

46,

47]. This makes it possible to identify tourist clusters of shared landscapes, linked to experiential tourism, that represent collective identity values recognized by insiders and outsiders.

The sample of specific individuals who participated in the survey is indicative, in qualitative terms, of the users of the landscape (insiders and outsiders) who are potentially interested in the alternative promotion activities of the park area under study.

The sample was identified in the field during activities and events organized as part of the LL. In particular, for the insiders, the following were selected: (i) the inhabitants present in the places where the activities took place, who do not play an active role; (ii) the inhabitants recognized by the community as experts. For outsiders, the following were selected: (i) the experts and scholars who have participated in scientific promotion events in the area or who have a consolidated knowledge of years of research and fieldwork; (ii) regular tourists of the area, interested in expanding their knowledge of the park.

The specific objective of the survey is to improve the involvement of insiders in the activities promoted by local groups, experimenting with different methods of collecting information, functional to the interaction with different users, and the return of data that can be analyzed. Inhabitants, tourists, and park scholars were then interviewed in three distinct ways, returning different results. The choice between semi-structured interviews or face-to-face questionnaires was made based on the interest of the interviewee and his or her knowledge of the area. Finally, online questionnaires were disseminated through Facebook social channels.

The semi-structured interviews and questionnaires, based on simple and general open questions, aimed to identify places in the park and to understand the characteristics that determine their value for the inhabitants and for those who frequent the territory, even temporarily. This approach to the landscape is, therefore, close to the indications of the European Convention, stimulating people to express the vision of the environment in which they live and structuring ways and tools to detect this type of information. Reasoning by values implies the exploration and search for ways to detect subjective fields. The value of a place is not necessarily attributed to objective requirements (site, heritage, humanity), but it can depend on subjective parameters (ability to contribute to the meaning and need for community); it can reside «

in the close, cognitive, confidential relationship between place and person; this seems also demonstrated by the spatial punctuality and topographical precision with which the places are marked— a house, a school, a church, a tree, a precise path, a clearly recognizable open space, a natural setting. The relationship, and therefore the value, are more often constructed by points, by microcosms.» [

21].

Through semi-structured interviews, the aim is to return thematic routes of the park, starting from the paths indicated by the interviewees and the explanation of tangible and intangible resources, thus detecting useful information for the promotion and enhancement of the park. In fact, the interview identifies the reason, the potentially interested public, the preferable period, and the means of transport with which to travel the route. Finally, the interviewee is also asked to indicate a slogan that re-assumes a way of life and promotes the park.

For the survey, two versions were developed: one frontal and one online.

The front survey was used to indicate ‘places of value’ [

18]. The goal is also to collect reports from interlocutors who do not have in-depth/itinerant knowledge of the area and for them to write down the places that are significant in their lives or places they would recommend for a friend to visit. Each place is associated with the following: reason, potentially interested audience, preferable season, means of transport, and slogan.

The online survey was developed from the indications obtained from the first results of the front survey, which facilitated the selection and organization of multiple and single choice questions and provided useful information for the alternatives of closed answers. The online survey system used was LimeSurvey, integrated with the Sila Labscape platform. The system features allowed the use of maps and interactive systems to indicate the order of preference for multiple responses.

Both the semi-structured interview and the frontal questionnaire proved capable of establishing conversational and simple contact with the interlocutors. Different categories of users, in fact, answered the questions with ease and availability, interacting with the research and acting as an intermediary to other interlocutors whose point of view and knowledge of the territory were considered relevant. The simplicity of interacting, starting from the topic of places, testifies that talking about places is a need that must be stimulated and ‘cultivated’ [

21]. It should be noted that in some cases, a place was marked for the possibility of knowing a person or the story of an experimental project, helping us to build a network of contacts and information.

4.2. Design Phase

The Design phase concerns the spatial representation of landscape perceptions. Spatial representation of thematic maps and the routes of places of value in the landscape, as perceived by the community [

18], was derived based on the information provided by the interviewees regarding the names of their favorite places and the relative weight given to each place.

Through the use of geo-statistic techniques and with the aid of a geographic information system (GIS), the ‘places of value’ (places where users find a particular sense of belonging) indicated by the park community were mapped and new tourist routes within the park traced.

In this field, research indicates that qualitative aspects can be more easily recognized and, therefore, mapped on a local scale [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Over the years, the geography that deals with the representation of the territory, which uses the point of view linked to human presence, has become a social science; an important role is assigned to meanings, that is, the images and ideas that the subject draws from observation. The representation of the landscape is, therefore, qualitative research that uses soft data. The latter, if located in space, can also contribute to the interpretation of the qualities of a territory that concern its physical characteristics.

To analyze and edit spatial data and map cartographic data, the very versatile open-source software QGIS was used, which allows the use of data from different sources.

For exploratory analysis of the data, we used Explorative Data Analysis (EDA), a part of statistics aimed at investigating data of which little knowledge is available [

52]. This approach aims to develop interpretative skills by stimulating knowledge of little-explored phenomena. EDA uses all available data, interpreting them through graphic techniques, even if not very formal, suggestive, and indicative, to bring out the structures and any aggregation rules or anomalies from the data (in their spatial connotation) [

52]. Furthermore, in the field of analysis, the use of techniques such as Explorative Data Spatial Analysis (ESDA) allows us to investigate the spatial models of places and values, the spatial association between them, and the systematic variation of phenomena in different places [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

4.3. Choice Phase

This phase is aimed at evaluating and choosing the directions of the local development of the SNP for the sustainable development of tourism, according to the two alternative scenarios identified: the ‘cultural tourism‘ route and ‘nature tourism’ route.

Hence, the question relating to the decision-making context is the following: ‘Which alternative development direction is preferable for Sila National Park’?

Starting from this main objective, the decision problem was structured according to the Analytic Network Process (ANP) method, performed using the software Superdecisions [

58,

59,

60].

ANP is a Multiple Criteria Decision Aid (MCDA) method that allows the outpacing of the rigidity of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) by Thomas L. Saaty [

57] because it includes the interrelationship between elements of a network of criteria [

58], taking into account the internal and external dependencies between sets of criteria [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63].

Concerning the case study, the ANP compensatory multi-criteria method was, therefore, chosen to investigate the relationships between the multiple functions of the landscape and the priorities of the knowledge domains involved in achieving the objective.

In ANP, the definition of the sets or clusters (i.e., objective, criteria, and alternatives) that contain subsets of nodes (i.e., the internal elements that characterize the criteria) and the global priorities of the alternatives can be obtained with the pairwise comparison technique [

58,

59,

60].

In the case study, the ANP method was divided into four main steps: the first step made it possible to define the main objective of the analysis, relating to the ‘definition of the sustainable routes for tourism-oriented development of the SNP’; in the second step, the decision-making problem was divided into two fundamental elements: the clusters that constitute the criteria and the nodes that are composed of the indicators.

The criteria (clusters), which represent the thematic categories of the indicators, taking into account the two alternatives under comparison, are represented by the functions of the landscape and related landscape services.

According to De Groot, landscape functions and related services can be divided into four macro-functions; furthermore, each macro-function can be described by several indicators that represent the local significance of the function [

64,

65,

66,

67].

Four domains are conceived as clusters of the network: Tourism (TU), Environment (EN), Cultural (CU), and Economic (EC), while ten sustainability indicators represent the nodes of the network.

The criteria, representative of the landscape functions identified for the SNP, are shown in

Table 1, which shows the classification of the function, the spatial indicators, the direction of preference, and the ID of each spatial indicator.

Each function is explained through the spatial criteria/indices derived from the characteristics of the landscape and the related spatial indicators, as described below:

Tourism (TU). The specific functions considered within this category are tourist facilities, housing, and transport, while the following five indexes have been expressed: density of accommodation facilities; density of catering services; index of uninhabited dwellings; population density; accessibility index.

Environment (EN). The specific functions related to this category include the environmental regulation provided for natural areas, represented by the ecological integrity index [

39].

Culture (CU). Specific functions involve cultural ecosystem services that provide cultural, artistic, and aesthetic information relating to historical and cultural heritage and places where traces of past human activities are preserved. These functions are represented by the following three indices: density of cultural sites; index of cultural events; density of the most photographed places.

Economics (EC). Economic function falls into this category since it is fundamental for the extraction of raw materials for human life; for this category, the only indicator provided relates to the average value of agricultural land.

In the third and fourth steps, the network model was built, the dependencies between the indicators were explored, and the priorities between clusters and nodes were defined.

These activities were carried out thanks to two focus groups with a team of local stakeholders, divided into promoters (mayors, the park authority of the Calabria region, local action groups); operators (cultural associations that promote local resources and knowledge); tourism agencies; cooperatives of local agricultural producers; professionals and inhabitants; and experts (urban planners, architects, and economists).

In the first focus group, the interactions between the different landscape functions were studied, and the internal and external dependencies between the indicators were explored. This made it possible to build the network model (

Figure 2), which highlights the relationships and interactions between nodes (indicators) and clusters (criteria represented by the functions of the landscape).

In the second focus group, the experts discussed their preferences at the node and cluster levels and established their priorities through pairwise comparisons.

Furthermore, to facilitate the comparison between the two scenarios, namely, Scenario A1—the cultural tourism route and Scenario A2—the Nature tourism route, Scenario A0 was added to represent the current state of the park landscape as the alternative of non-intervention, conceived as a control scenario to analyze the two scenarios of A1 and A2.

Finally, a sensitivity analysis was developed to verify the consistency of the final judgments.

5. Results

The results of the proposed methodological approach for structuring an SDSS [

27,

28,

29,

30] are described in the following sections.

The methodological approach articulated in the four main phases of Intelligence (i), Design (ii), Choice (iii), and Outcome (iv) helps us to explore planning support systems.

It allows the improvement of knowledge of the context, the evaluation of local resources, and the development of sustainable development strategies in fragile contexts, where the conditions of socio-economic crisis make development processes more difficult.

5.1. Intelligence Phase: Results

In the Intelligence phase, the processing of the soft data obtained from the surveys made it possible to obtain relevant indicators on the subjective perception of the stakeholders regarding ‘places of value’. This allowed the identification of tourist clusters/domains of shared landscape, linked to experiential tourism, that represent collective identity values recognized by insiders and outsiders.

Therefore, starting from the paths and ‘places of value’ indicated by people, it is possible to analyze human behavior by exploring the territory and attributing values to a stratified reality, such as the landscape under study [

43]. Human beings, in fact, move in space to orient themselves and keep the memory of their perceptions. The paths, therefore, represent the connection of people to places and games to read the dynamics and different ways of experiencing the landscape.

The processing of the information contained in the interviews makes it possible to geographically and spatially locate the places that insiders and outsiders have indicated in their routes.

Each interview was then returned through a specific route (a succession of points in geographical space) to which, following semantic analysis, a theme was attributed regarding some fields of the interview relating to reasons for the trip, slogans, and potentially interested audiences [

44]. The processing of the interview data highlighted some recurring semantic fields.

Furthermore, through subsequent frequency analysis, we then selected some relevant keywords associated with each main semantic field. The comparison between all the keywords that emerged in all the interviews made it possible to identify some subjective semantic fields common to the two groups of users (insiders and outsiders) relating to identity, community, discovery, wellbeing, and quality of life. The subjective fields have been identified to represent the identity values of the landscape shared by the interviewees.

It also emerged, quite recurrently, that the motivation of the route (the theme) was very often the combination of several fields.

The survey through questionnaires, still in progress on the online channel, returned, in its partial results, the postcards of ‘places of value’ for insiders and outsiders. What is required is to try to convey the territory through the images, words, and advice of those who have traveled it, aiming to collect suggestions, comments, and preferences.

A ‘when’ field was added to the online survey for possible indication of the order of preferability of seasons. This response method was also chosen to identify the categories of users potentially interested in visiting the indicated place (e.g., lover of nature, lover of culture, lover of fun, inhabitant, inhabitant of the city, expert, sportsman).

Through appropriate corrections, combining open and closed, single and multiple responses (in order of preference), the survey was modified for offline (front) and online channels, adding in the latter the possibility of attaching photos and comments. It is significant to highlight how the ‘photo name/comment’ field has made it possible to trace a specific place, often not expressly indicated in the ‘place of value’ field, which, in some cases, provides information on the more emotional and perceptive aspects of it.

From the calculations, therefore, emerges an order of preference of the places of value, as reported by insiders and outsiders. The preference is the result of the frequency and order in which the places are named by users. Each interviewee can, in fact, reported a maximum of three places when indicating additional information (trip’s reason, type transportation, period, trip’s recipients, slogans, photos, comments). In the multiple-choice fields, with alternatives to be sorted, the preference (frequency and sorting) is elaborated; in the single answer fields, where only one of the alternatives listed is select, the frequency is processed. Semantic analysis was carried out on the open-ended fields, tracing the keywords.

Ultimately, through the examination of the values perceived by the interviewees, it was possible to recognize, through frequency analysis, some recurrent keywords; those that are more frequent express the emotionally subjective component given to a certain experience that belongs to the same area of meaning/semantic field [

44,

45,

46,

47]. This, therefore, allows the selection of tourist clusters/domains of a shared landscape, linked to experiential tourism, that are representative of collective identity values recognized by insiders and outsiders. What emerged was that there are two main tourist clusters, identified using related associated keywords, that represent a wide range of aspects of the perceived landscape, appreciated and shared by the interviewees:

Cultural tourism (A1), which aims to promote and enhance cultural tourism and local identity through the enhancement of places of cultural interest, the tasting of typical products, as well as the use of naturalistic places in the park. The set of keywords that represent the cultural tourism cluster are:

- -

Identity: community relations, landscape, hospitality, food;

- -

Discovery: known, hidden, in extinction, not well-known, submerged, heritage, culture, historic towns, towns in a state of abandon, water, local food, local crafts and knowledge, encounter, landscape, traditional holiday.

Nature tourism (A2), which mainly aims to promote naturalistic tourism, personal wellbeing, implementing quality of life through slow mobility and the improvement of services, as well as promoting experiences related to ‘food routes’. The set of keywords that represent the natural tourism cluster are:

- -

Wellbeing: quality of life, tranquillity, healthy life, peaceful life, wellbeing involvement, finding oneself, recovery of the meaning of life, recovery of your dreams, peace within, freedom, traditions, gastronomy relaxation, sea hospitality, landscape, culture, uniqueness, natural oasis.

5.2. Design Phase: Results

In the Design phase, the locations cited by the interviewees are represented in the QGIS environment, an open-source geographic information system, which, together with the Google Earth and Google Maps applications, make it possible to produce a model for spatial representation of the perceived landscape [

54,

55].

Google Earth and Google Maps proved to be very useful tools for representing the park’s landscape through the points/places most photographed by users [

56]. The geographical representation of the places, together with an archive of geo-localized photos, shared among users, in addition to enriching the maps and providing information on the specific geographical position of the places, highlighted the shared values, their local meanings, and two main tourist clusters—cultural tourism and nature tourism, represented and traced for each cluster, respectively (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Subsequently, in agreement with other studies, the information contained in the interviews made it possible to interpret the importance related to each of the places [

21]. This was possible as each place was weighted according to the importance assigned by the interviewees and the accuracy in the description of the place itself, identified as a point. Weight 3 was, therefore, assigned if the interviewee indicated the name of a specific place, Weight 2 if the name of a fraction of a municipality and a very photographed point on Google Maps was indicated with the reference area, and Weight 1 if the respondent indicated the name of a municipality.

After tracing the routes on maps, subsequent processing and analysis of the spatial data were carried out using kernel density estimation (KDE), which returns for each interviewee the areas with the greatest density of points and takes into account relative weight and proximity relationships.

The kernel function used was the ‘triple weight’, which gives greater importance to the nearby points/places indicated in each route and the relation to the frequency of recurring keywords (identity, community, discovery, wellbeing, quality of life) [

57].

The restitution of the user maps concerning each theme/cluster was carried out to a ‘radius of perception’, expressed in km.

Subsequently, based on the rays of action of various types of users, a subsequent KDE analysis was carried out, which highlighted the most significant areas of interest for each type of route, with a high concentration of points (places) reported by insiders and outsiders. Therefore, for each route, the areas with the highest density of points, the most representative places, with their relative meanings and associated relationships, were identified (

Figure 5).

5.3. Choice Phase: Results

Table 2 and

Table 3 show, respectively, the two results of the Choice phase obtained from the application of the ANP, consisting of the weighted and limiting super-matrices that combine external and internal interdependencies between clusters and nodes and weights expressed by the priority vectors relating to each main category [

58,

59,

60,

61,

64,

65,

66,

67].

Finally, the final output of the ANP provides the final ranking, highlighting the cultural tourism route (A1) as the most suitable scenario to be implemented for the achievement of the main objective.

Table 4 provides the weight of each indicator, namely, ‘normalized by cluster’ and ‘limiting’ values, while the ‘normalized by indicators’ value highlights the contribution of each indicator. This last piece of information allows us to identify the most suitable areas for the implementation of Scenario A1 (cultural tourism route).

5.4. Outcome Phase: Result

The final result of the evaluation process of the Outcome phase is represented by the composite maps of the multi-functionality of the landscape. The individual maps describe the landscape of the SNP with the related landscape services, highlighting the most suitable areas to achieve better performance of landscape functions and which municipalities of the park would most benefit if Scenario A1 (cultural tourism route) was pursued.

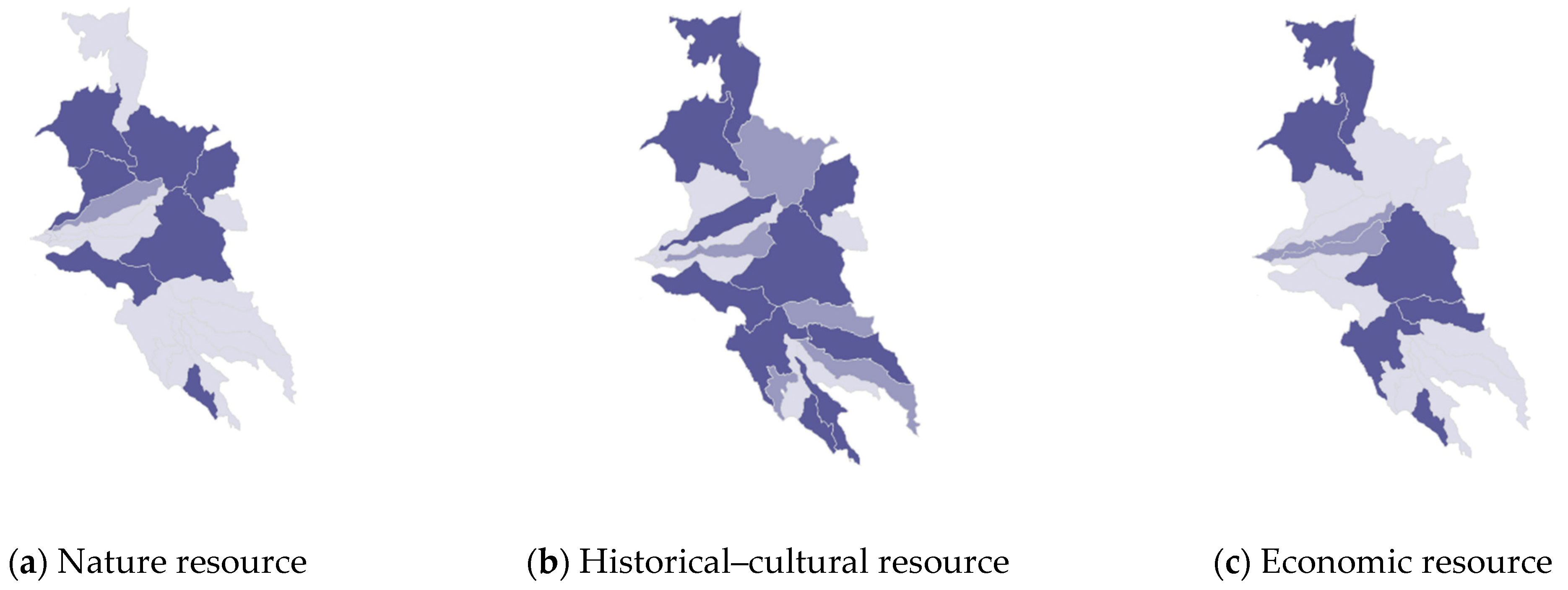

In detail, the information maps provide the density of the services offered by the cultural landscape of the SNP, with nature, historical–cultural, and economic resources.

The information on cultural landscape services (CLS) was processed and geo-referenced in a GIS environment, providing a synthetic cognitive framework useful for classifying the different municipalities of the park according to the different levels of density of services, evaluated on a chromatic scale: high, medium, low (

Figure 6).

6. Discussion

Starting from a multi-disciplinary background, the research uses an evaluation framework aimed at investigating the conditions that stimulate territorial co-creativity towards regenerative models of the cultural and nature landscape [

8,

41,

67].

The multi-stakeholder approach was useful for developing deeper knowledge and awareness of local qualities and potential in order to support decision-makers in defining collaborative local strategies for tourist enhancement of local resources, especially in fragile contexts.

Through the integration of different methods and interpretative and evaluative tools, a decision-making process was developed for the enhancement of the SNP’s landscape and its endogenous resources, useful for reconstructing an ‘affective geography’ of ‘places of value’ and new itineraries of tourism that represent the concept of wellbeing, as perceived by SNP’s community [

68,

69].

The experimentation, in the light of the results obtained, highlights a methodological process capable of (i) exploring the demand for landscapes as a common good; (ii) activating a path of co-learning and self-assessment that brings out the interdependent nature of links, relationships, and value chains; (iii) tracing the meanings and spatial relationships in the landscape; and (iv) experimenting with regenerative landscape models through the development of new value chains [

68,

70].

Thinking in terms of values, in fact, requires the identification of new ways of representing the landscape, going beyond the classification of homogeneous characters to investigate the differences and specificities of territory, made up of hidden, invisible components, such as the processes that generated it and those that unconsciously guide the transformations taking place [

16,

18,

71].

In this research, the integration of evaluation methods and tools was tested to detect the local meanings of categories of universal value [

70]. The dynamic approach of the Cultural Values model represents the guide with which the information is classified [

20]. Starting from the mapping of the physical characteristics and meanings attributed to places, a series of analyses was developed that made it possible to investigate the values in a relational and multi-dimensional dimension [

70,

72,

73,

74]. Subsequent representations are, therefore, an expression of the intrinsic value attributed to places and a potential value that invites us to reflect on a new way to view resources and their use [

15,

75,

76,

77]. The representation of the landscape thus becomes a moment of learning, awareness, and planning possible actions.

From this perspective, the methodological framework is thus configured as an instrument of knowledge and enhancement of local landscapes; an alternative to traditional tourism planning and the promotion processes of territories constitutes a research field that is still open, from which some relevant results have emerged.

These certainly include (i) the evident connection between the assigned meanings and the perceived values of the landscape according to the components of the Cultural Value model; (ii) the recognition of the subjectivity of the objective environment; (iii) the representation of the perceived landscape and further interpretations of it [

23,

40,

41].

The results are to be considered reliable as they are derived from rich and detailed information, the result of interactions and comparisons between different points of view of outsiders and insiders who have discussed and assessed, in depth, the reasons and importance given to the recognition of meanings attributed to ‘places of value’.

Field research will continue on the concept of the Human Smart Landscape as a regenerative model in which solutions are developed in a specific context, thanks to the interaction between expert knowledge and common knowledge. This is a research field that is still open, in which new approaches and tools for the representation, evaluation, monitoring, and management of landscapes are being tested [

8,

18,

78,

79,

80].

The HSL is configured as a complex space attentive to social cohesion, creativity, and quality of life, in which citizens play a central role: there is a need for actions capable of integrating the design of spaces and infrastructure, reducing the consumption and waste of resources, in order to recover cultural and environmental heritage in sustainable terms, to create synergies with nature, rural and urban areas, to make a qualified use of ecological networks, to enhance the different forms of culture consciously, to enhance the attractiveness of the landscape, helping to improve the quality of spaces, use, and relationships [

22,

63,

64,

67,

78,

79,

80].

7. Conclusions

The research proposes a Spatial Decision Support System (SDSS) for the evaluation of multi-functional landscapes that aims to help local actors to understand the local resources and multi-functional values of Sila National Park (SNP) in southern Italy, stimulating their cooperation in the management of environmental and cultural sites and the co-design of new enhancement strategies and new tourist services.

The processes activated in the Sila Labscape experiments investigated the potential of the spontaneous transmission of knowledge and the availability of mutual, interactive, and collaborative learning between insiders and outsiders, useful for supporting social and territorial innovation processes.

The most relevant results of the experimentation concerned the integration between different methods and interpretative and evaluative tools that have made it possible to reconstruct an ‘affective geography’ of the territory through the recognition of the subjectivity of the objective environment, its representation in space, and further interpretations of it. The values attributed to the SNP landscape were investigated, starting from the routes in the park that specific users and citizens reported. Emotional ties with the landscape were then explored, and the spatial relationships linked to the perception of ‘places of value’ were identified. In this way, the landscape is perceived as a lived and potential experience that allows us to interpret the physical qualities of the area with regard to its significance for certain individuals and the community that lives in the park.

The perceived qualities, linked to the values of local resources and the territory, have made it possible to trace new thematic itineraries in which the ‘places of value’ are linked to the quality of life of individuals, reflecting the concept of wellbeing, as perceived by a community. The new maps of shared landscape values describe the affective itineraries in which personal values and relationships are concentrated, thus giving back the opportunity to experience a tourist landscape in the park, discovering the dynamics that characterize it.

The model for the spatial representation of the perceived landscape, integrated with the ANP method, also supports the identification of a preferable scenario capable of activating a transformative resilience strategy in vulnerable internal areas that can be expanded into other similar contexts.

Finally, the final result of the evaluation process is represented by composite maps of the multi-functionality of the landscape with related landscape services that highlight the most suitable areas for the best performance of landscape functions and which municipalities of the park would benefit most.

Composite maps can be considered the starting point of the decision-making process, useful for activating a dialogue between decision-makers, stakeholders, and local communities to enhance the resources of the territory and promote a transformative territorial network strategy, starting from the site-specific identification of enhancement opportunities of the park.