Cultural and Creative Cities and Regional Economic Efficiency: Context Conditions as Catalyzers of Cultural Vibrancy and Creative Economy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Cultural and Creative Cities in the Development of Their Region

2.2. The Importance of Context Conditions in Catalyzing the Impact of CCCs

3. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor Database

4. Methodology: The Impact of Cultural and Creative Cities on Their Regional Economies

5. Results

6. CCCs and Regional Output: Some Deeper Reflections

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation. Getting Cultural Heritage to Work for Europe, Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on Cultural Heritage. 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/news/getting-cultural-heritage-work-europe (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on the Work Plan for Culture 2019–2022 (2018/C 460/10). 2018. Available online: europa.eu (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- UNCTAD. Creative Economy Report. 2008. Available online: http://unctad.org/en/docs/ditc20082cer_en.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2018).

- UNCTAD. Creative Economy Report. 2010. Available online: http://unctad.org/en/Docs/ditctab20103_en.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2018).

- European Commission. ‘Green Paper—Unlocking the Potential of Cultural and Creative Industries’. 2010. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1cb6f484-074b-4913-87b3-344ccf020eef/language-en (accessed on 8 December 2018).

- Faro Convention—Council of Europe, Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. 2005. Available online: http://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680083746 (accessed on 3 May 2018).

- European Commission. Communication towards and Integrated Approach to Cultural Heritage for Europe; 477 Final; COM: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Landry, C.; Bianchini, A.F. The Creative City, Demos. 1995. Available online: https://www.demos.co.uk/files/thecreativecity.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Zukin, S. The Cultures of Cities; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P. Cities in Civilization; Pantheon: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A. The Cultural Economy of Cities; SAGEL: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, L.C.; Sanz, J.Á.; Devesa, M.; Bedate, A.; Del Barrio, M.J. The economic impact of cultural events—A case study of Salamanca 2002, European Capital of Culture. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2006, 13, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, B. The return on investment of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2006, 30, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffe, X. Heritage conservation as a driving force for development. In Heritage and Beyond; Council of Europe Publishing: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806abdea (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Yang, C.; Lin, H.; Han, C. Analysis of international tourist arrivals in China: The role of World Heritage Sites. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patuelli, R.; Mussoni, M.; Candela, G. The effects of World Heritage Sites on domestic tourism: A spatial interaction model for Italy. J. Geogr. Syst. 2013, 15, 369–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Snowball, J.D. The economic, social and cultural impact of cultural heritage: Methods and examples. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Rizzo, I., Mignosa, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marlet, G.; van Woerkens, C. The Dutch creative class and how it fosters urban employment growth. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 2605–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, D.; Wojan, T. Recasting the creative class to examine growth processes in urban and rural counties. Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R.; Mellander, C.; Stolarick, K. Inside the black box of regional development: Human capital, the creative class and tolerance. J. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 8, 615–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boschma, R.A.; Fritsch, M. Creative Class and Regional Growth: Empirical Evidence from Seven European Countries. Econ. Geogr. 2009, 85, 391–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel-Molina, B.; Hervas-Oliver, J.L.; Boix, R.; de Miguel-Molina, M. The importance of creative industry agglomerations in explaining the wealth of European regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrocu, E.; Paci, R. Education or creativity: What matters most for economic performance? Econ. Geogr. 2012, 88, 369–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marrocu, E.; Paci, R. Regional development and creativity. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2013, 36, 354–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boix, R.; de Miguel, B.; Hervas, J.L. Creative service business and regional performance: Evidence for the European regions. Serv. Bus. 2013, 7, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix-Domenech, R.; Soler-Marco, V. Creative service industries and regional productivity. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2017, 96, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggian, A.; Partridge, M.; Malecki, E. Creating an environment for economic growth: Human capital, creativity or entrepreneurship? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CHCFE. Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe: Full Report; Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe—Europa Nostra: Venice, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Promoting Cultural and Creative Sectors for Growth and Jobs in the EU. 2012. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/registre/docs_autres_institutions/commission_europeenne/com/2012/0537/COM_COM%282012%290537_EN.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Tom Fleming Creative Consultancy. Cultural and Creative Spillovers in Europe: Report on A Preliminary Evidence Review. 2015. Available online: https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/Cultural_creative_spillovers_in_Europe_full_report.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Lazzaro, E. Linking the creative economy with universities’ entrepreneurship: A spillover approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, H.; McVittie, E.; Simmie, J. Creating Innovation. Do the Creative Industries Support Innovation in the Wider Economy; NESTA: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Werck, K.; Heyndels, B.; Geys, B. The impact of ‘central places’ on spatial spending patterns: Evidence from Flemish local government cultural expenditures. J. Cult. Econ. 2008, 32, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sacco, P. Culture 3.0: A New Perspective for the EU 2014–2020 Structural Funds Programming, EENC Paper. 2011. Available online: http://www.interarts.net/descargas/interarts2577.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Leadbeater, C. (Ed.) Living on Thin Air; Penguin: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.R.; Kabwasa-Green, F.; Herranz, J. Cultural Vitality in Communities: Interpretation and Indicators. Culture, Creativity and Communities Program, Urban Institute. Cultural Vitality in Communities: Interpretation and Indicators. 2006. Available online: urban.org (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Montalto, V.; Moura, C.J.T.; Langedijk, S.; Saisana, M. Culture counts: An empirical approach to measure the cultural and creative vitality of European cities. Cities 2019, 89, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossetto, G.; Vecco, M. (Eds.) Economia del Patrimonio Monumentale; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Towse, R. (Ed.) A Handbook of Cultural Economics; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bowitz, E.; Ibenholdt, K. Economic impacts of cultural heritage—Research and perspectives. J. Cult. Herit. 2009, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J. Heritage and local development: A reluctant relationship. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Rizzo, I., Mignola, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Cultural capital. J. Cult. Econ. 1999, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPON. HERITAGE-The Material Cultural Heritage as a Strategic Territorial Development Resource: Mapping Impacts through a Set of Common European Socio-Economic Indicators. 2019. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/cultural-heritage (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Light, D.; Creţan, R.; Voiculescu, S.; Jucu, I.S. Introduction: Changing Tourism in the Cities of Post-communist Central and Eastern Europe. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2020, 22, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanolo, A. The image of the creative city: Somereflections on urban branding in Turin. Cities 2008, 25, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesalon, L.; Crețan, R. “Little Vienna” Or “European Avant-Garde City”? Branding Narratives in A Romanian City. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2019, 11, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Petit, S.; Seetaram, N. Measuring the Effect of Revealed Cultural Preferences on Tourism Exports. J. Travel Res. 2018, 58, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faber, B.; Gaubert, C. Tourism and Economic Development: Evidence from Mexico’s Coastline. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 6, 2245–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panzera, E.; de Graaff, T.; de Groot, H.L. European cultural heritage and tourism flows: The magnetic role of superstar World Heritage Sites. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2021, 100, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffe, X. Is heritage an asset or a liability? J. Cult. Herit. 2004, 5, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerisola, S. A new perspective on the cultural heritage-development nexus: The role of creativity. J. Cult. Econ. 2019, 43, 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R.; Cerisola, S.; Panzera, E. The Cultural Heritage—Territorial Capital nexus: Theory and empirics, Il capitale culturale. Supplementi 2020, 11, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzera, E. The Socio-Economic Impact of Cultural Heritage and the Role of Territorial Identity. (unpublished).

- Wilson, N.; Gross, J.; Bull, A. Towards Cultural Democracy—Promoting Capabilities for Everyone. King’s College London. 2016. Available online: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/cultural/resources/reports/towards-cultural-democracy-2017-kcl.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2021).

- Turok, I. Cities, Clusters and Creative Industries: The Case of Film and Television in Scotland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2003, 11, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, K.; Daniel, R.; Welters, R. Developing a regional economy through creative industries: Innovation capacity in a regional Australian city. Creat. Ind. J. 2017, 10, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P.; Lazzeretti, L. (Eds.) Creative Cities, Cultural Clusters and Local Economic Development; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Storper, M. Innovation as Collective Action: Conventions, Products and Technologies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 1996, 5, 761–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, J. Why creative industries matter to economic evolution. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2009, 18, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerisola, S. Cultural Heritage, Creativity and Economic Development; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, E.J. Inequality and politics in the creative city region: Questions of livability and state strategy. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.E. Creative people need creative cities. In Handbook of Creative Cities; Andersson, D.E., Andersson, A.E., Mellander, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simonton, D.K. Big-C creativity in the big city. In Handbook of Creative Cities; Andersson, D.E., Andersson, A.E., Mellander, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN HABITAT. The New Urban Agenda (NUA). Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/12/nua_handbook_14dec2020_2.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Castells, M. (Ed.) The Rise of the Network Society; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Collier Macmillan: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Territorial Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). Territorial State and Perspectives of the European Union, Scoping Document and Summary of Political Messages, May; 2005. Available online: https://www.ccre.org/docs/territorial_state_and_perspectives.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Camagni, R. Towards a concept of territorial capital. In Modelling regional Scenarios for the Enlarged Europe; Capello, R., Camagni, R., Chizzolini, B., Fratesi, U., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R. Territorial capital and regional development: Theoretical insights and appropriate policies. In Handbook of Regional Growth and Development Theories—Revised and Extended Second Edition; Capello, R., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 124–148. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, R.; Perucca, G. Cultural capital and local development nexus: Does the local environment matter? In Socioeconomic Environmental Policies and Evaluations in Regional Science—Essays in Honor of Yoshiro Higano; Shibusawa, H., Sakurai, K., Mizunoya, T., Uchida, S., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; pp. 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R. On the mechanism of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators 2006; OECD: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Faggian, A.; McCann, P. Human capital and regional development. In Handbook of Regional Growth and Development Theories; Capello, R., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P.R. Geography and Trade; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, B. Infrastructure, accessibility and economic growth. Int. J. Transp. Econ. 1993, 20, 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman, R.; Spiekermann, K.; Wegener, M. Accessibility and Economic Development in Europe. Reg. Stud. 1999, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Karlsson, C. Knowledge in regional economic growth—The role of knowledge accessibility. Ind. Innov. 2007, 14, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, R.; Nanetti, R.Y. (Eds.) Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, S.; Kitson, M.; Toh, B. Social capital, economic growth and regional development. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 1015–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. (Eds.) Why Nations Fails: The Origin of Power, Prosperity and Poverty; Profile: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huggins, R.; Thompson, P. Culture and Place-Based Development: A Socio-Economic Analysis. Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 130–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicerchia, A. Evidence-based policy making for cultural heritage. Sci. Res. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- JRC. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor. Composite Indicators. 2019. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC117336 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Montalto, V.; Moura, C.J.T.; Langedijk, S.; Saisana, M. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor. 2019 Edition; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, M.; Lovatt, A.; O’Connor, J.; Raffo, C. Risk and trust in the cultural industries. Geoforum 2000, 31, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, D. Are there returns to scale in city size? Rev. Econ. Stat. 1976, 58, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marelli, E. Optimal City Size, the Productivity of Cities and Urban Production Function. Sist. Urbani 1981, 1, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, R.; Cerisola, S. Concentrated versus diffused growth assets: Agglomeration economies and regional cohesion. Growth Chang. 2020, 51, 1440–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, V.; Moura, C.J.T.; Langedijk, S.; Saisana, M. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor. 2017 Edition; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity—Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J. The nature of creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2006, 18, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hemlin, S.; Allwood, C.M.; Martin, B.R. Creative knowledge environments. Creat. Res. J. 2008, 20, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L. The creative capacity of culture and the new creative milieu. In A Handbook of Industrial Districts; Becattini, G., Bellandi, M., de Propris, L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baycan, T. Creative cities: Context and perspectives. In Sustainable City and Creativity—Promoting Creative Urban Initiatives; Girard, L.F., Baycan, T., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. Towards a New Interpretation of Regional Evolution: Convergence between Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches; Revue D’économie Régionale et Urbaine (RERU); Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2020; Volume 4, pp. 591–616. [Google Scholar]

- Comunian, R.; Faggian, A.; Li, Q.C. Unrewarded careersin the creative class: The strange case of bohemian graduates. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2010, 89, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L. Review of Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2005, 35, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markusen, A. Urban development and the politics of a creative class: Evidence from a study of artists. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 1921–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peck, J. Struggling with the Creative Class. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2005, 29, 740–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donegan, M.; Lowe, N. Inequality in the Creative City: Is There Still a Place for “Old-Fashioned” Institutions? Econ. Dev. Q. 2008, 22, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Florida, R. The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—And What We Can Do about It; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. Cities and the Creative Class; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.Y.; Xie, W. Creativity and Inequality: The Dual Path of China’s Urban Economy. Growth Chang. 2013, 44, 608–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A.C. The cultural contradictions of the creative city, City. Cult. Soc. 2011, 2, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorenzen, M.; Andersen, K.V. Centrality and Creativity: Does Richard Florida’s Creative Class Offer New Insights into Urban Hierarchy? Econ. Geogr. 2009, 85, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R. Who owns the name? Fandom, social inequalities and the contested renaming of a football club in Timişoara, Romania. Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; O’Brien, T. GET OUT OF TRAIAN SQUARE! Roma Stigmatization as a Mobilizing Tool for the Far Right in Timişoara, Romania. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creţan, R.; O’Brien, T. Corruption and conflagration: (In) justice and protest in Bucharest after the Colectiv fire. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comunian, R. Rethinking the Creative City: The Role of Complexity, Networks and Interactions in the Urban Creative Economy. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 1157–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.P. The “vicious cycle” of tourism development in heritage cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M. Overtouristified cities: An online news media narrative analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1805–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodirsky, K. Culture for competitiveness: Valuing diversity in EU-Europe and the ‘creative city’ of Berlin. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2012, 18, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- ESPON. Topic Paper—Synergetic Relations between Cultural Heritage and Tourism as Driver for Territorial Development: ESPON evidence. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/Topic%20paper%20-%20Tourism_0.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- URBACT Project. URBACT Project Results First Edition. Available online: https://urbact.eu/files/urbact-project-results-first-edition (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Sabatini, M. Tourism and Cultural Heritage for Regional Development, ESPON Webconference on Cultural Heritage and Tourism. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/espon-conference-tourism-and-cultural-heritage-regional-development (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Sacco, P. OECD Webinar on Culture, Creative Sectors, and Local Development. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Cultural and Creative Sectors: Impact, Innovations and Planning for Post-Crisis. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/culture-webinars.htm (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Crociata, A.; Agovino, M.; Sacco, P. Cultural access and mental health: An exploratory study. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Territorial Unit of Reference | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDP PPS | Gross domestic product at purchasing power standard measuring the output of the region | NUTS2 Region (or aggregation, see Figure 2) | Cambridge Econometrics |

| Capital Stock | Capital stock computed through permanent inventory method (pim) from data on gross fixed capital formation | NUTS2 Region (or aggregation, see Figure 2) | Cambridge Econometrics |

| Employment with tertiary education | Number of employed people with tertiary education proxying the quality of regional labour force | NUTS2 Region (or aggregation, see Figure 2) | Eurostat |

| Employment without tertiary education | Number of employed people without tertiary education | NUTS2 Region (or aggregation, see Figure 2) | Eurostat |

| Population | Population of each cultural and creative city included in the sample meant at controlling for size and urbanization economies | City | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor |

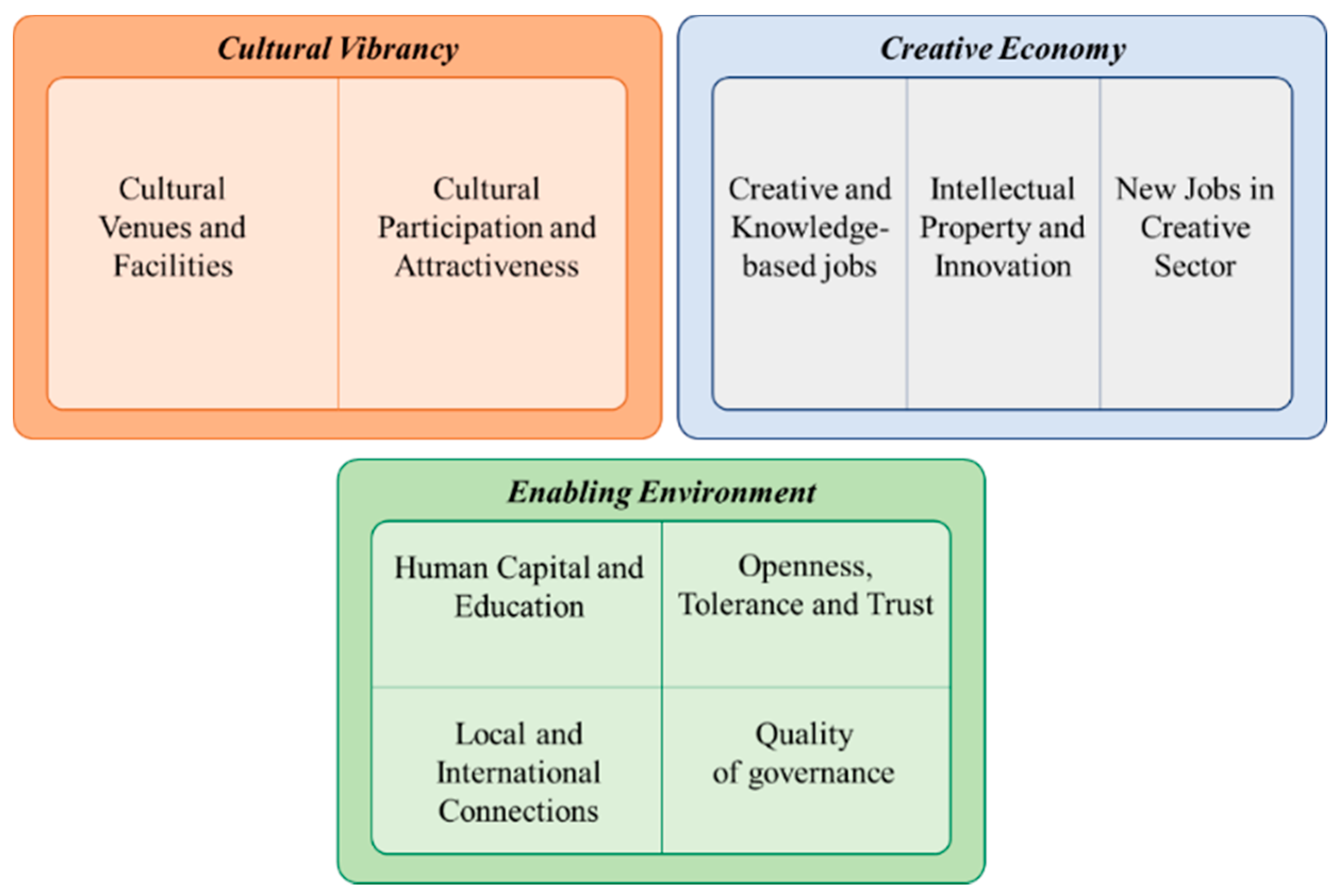

| Cultural Vibrancy | Cultural Venues and Facilities—Measure of physical quantities of culture-related venues such as sights and landmarks, museums and art galleries, cinemas, concert and music halls, theatres | City | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor |

| Cultural Participation and Attractiveness—Measure of the capacity of culture-related venues to attract audiences including tourist overnight stays, museum visitors, cinema attendance, satisfaction with cultural facilities | City | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor | |

| Creative Economy | Creative and Knowledge Based Jobs—Sectoral measure of creative economy including jobs in arts, culture and entertainment, jobs in media and communication, jobs in other creative sectors | City | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor |

| Intellectual Property and Innovation—Measure of creativity in terms of innovation including ICT patent applications and community design applications | NUTS3 | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor | |

| New Jobs in Creative Sectors—Dynamic measure of creative economy including new jobs in arts, culture and entertainment enterprises, new jobs in media and communication enterprises, new jobs in enterprises in other creative sectors | NUTS3 | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor | |

| Enabling Environment | Human Capital and Education—The indicator considers the number of graduates in arts and humanities and in ICT and the average appearances in university rankings | City | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor |

| Openness, Tolerance and Trust—The indicator includes foreign graduates, foreign-born population, tolerance of foreigners, integration of foreigners, and people’s trust, considered the conditions contributing to the flourishing of cultural and creative economies | City | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor | |

| Local and International Connections—Measure of local and international accessibility including passenger flights, potential road accessibility, and direct trains to other cities | City | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor | |

| Quality of Governance—Composite indicator measuring the quality of government concerning three domains: education, healthcare, and law enforcement | Region | Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Capital stock | 0.375 *** | 0.369 *** |

| (0.059) | (0.058) | |

| Employment with tertiary education | 0.082 * | 0.085 * |

| (0.044) | (0.045) | |

| Employment without tertiary education | 0.053 | 0.046 |

| (0.066) | (0.066) | |

| Population city | 0.029 | −0.048 |

| (0.027) | (0.096) | |

| Cultural vibrancy | 0.116 *** | |

| (0.042) | ||

| Cultural venues and facilities | −0.030 | |

| (0.087) | ||

| Cultural participation and attractiveness | 0.065 *** | |

| (0.024) | ||

| Time fixed effects | −0.078 *** | −0.078 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Constant | 5.225 *** | 6.526 *** |

| (0.971) | (1.810) | |

| No. of observations | 372 | 372 |

| R-squared (within) | 0.8846 | 0.8849 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Capital stock | 0.356 *** | 0.359 *** |

| (0.057) | (0.057) | |

| Employment with tertiary education | 0.106 ** | 0.096 ** |

| (0.046) | (0.045) | |

| Employment without tertiary education | 0.091 | 0.090 |

| (0.070) | (0.069) | |

| Population city | −0.031 | −0.033 |

| (0.023) | (0.025) | |

| Creative economy | −0.001 | |

| (0.017) | ||

| Creative and knowledge based jobs | −0.007 | |

| (0.013) | ||

| Intellectual property and innovation | 0.015 ** | |

| (0.006) | ||

| New jobs in creative sectors | −0.000 | |

| (0.010) | ||

| Time fixed effects | −0.080 *** | −0.082 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| Constant | 6.183 *** | 6.224 *** |

| (0.954) | (0.995) | |

| No. of observations | 372 | 372 |

| R-squared (within) | 0.8780 | 0.8815 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Capital stock | 0.382 *** | 0.346 *** |

| (0.064) | (0.064) | |

| Employment with tertiary education | 0.076 * | 0.084 ** |

| (0.045) | (0.038) | |

| Employment without tertiary education | 0.077 | 0.035 |

| (0.062) | (0.060) | |

| Population city | −0.240 ** | 0.009 |

| (0.112) | (0.015) | |

| Cultural venues and facilities | 0.515 ** | |

| (0.254) | ||

| Cultural venues and facilities × human capital and education | 0.044 * | |

| (0.024) | ||

| Cultural venues and facilities × openness, tolerance and trust | 0.076 *** | |

| (0.024) | ||

| Cultural venues and facilities × local and international connections | −0.325 *** | |

| (0.078) | ||

| Cultural venues and facilities × quality of government | 0.017 | |

| (0.015) | ||

| Cultural participation and attractiveness | −0.250 | |

| (0.166) | ||

| Cultural participation and attractiveness × human capital and education | 0.012 * | |

| (0.006) | ||

| Cultural participation and attractiveness × openness, tolerance, and trust | 0.081 ** | |

| (0.032) | ||

| Cultural participation and attractiveness × local and international connections | −0.070 ** | |

| (0.029) | ||

| Cultural participation and attractiveness × quality of government | 0.045 ** | |

| (0.019) | ||

| Human capital and education | −0.119 * | −0.036 |

| (0.064) | (0.023) | |

| Openness, tolerance and trust | −0.158 * | −0.173 * |

| (0.087) | (0.098) | |

| Local and international connections | −1.112 | −8.407 |

| (5.148) | (8.108) | |

| Quality of government | −0.095 ** | −0.163 *** |

| (0.041) | (0.054) | |

| Time fixed effects | −0.069 *** | −0.071 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.005) | |

| Constant | 13.114 | 31.552 |

| (14.994) | (23.438) | |

| No. of observations | 372 | 372 |

| R-squared (within) | 0.9044 | 0.9077 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital stock | 0.376 *** | 0.392 *** | 0.395 *** |

| (0.059) | (0.057) | (0.064) | |

| Employment with tertiary education | 0.083 ** | 0.053 | 0.085 * |

| (0.040) | (0.042) | (0.044) | |

| Employment without tertiary education | 0.061 | 0.024 | 0.054 |

| (0.061) | (0.064) | (0.065) | |

| Population city | −0.078 | 0.004 | −0.004 |

| (0.047) | (0.015) | (0.017) | |

| Creative and knowledge based jobs | −0.119 | ||

| (0.091) | |||

| Creative and knowledge based jobs × human capital and education | 0.018 | ||

| (0.012) | |||

| Creative and knowledge based jobs × openness, tolerance and trust | 0.035 * | ||

| (0.020) | |||

| Creative and knowledge based jobs × local and intern. Connections | −0.087 *** | ||

| (0.019) | |||

| Creative and knowledge based jobs × quality of government | 0.045 *** | ||

| (0.017) | |||

| Intellectual property and innovation | 0.055 | ||

| (0.053) | |||

| Intellectual property and innovation × human capital and education | −0.002 | ||

| (0.004) | |||

| Intellectual property and innovation × openness, tolerance, and trust | −0.026 * | ||

| (0.013) | |||

| Intellectual property and innovation × local and intern. Connections | −0.004 | ||

| (0.008) | |||

| Intellectual property and innovation × quality of government | 0.014 ** | ||

| (0.006) | |||

| New jobs in creative sectors | 0.045 | ||

| (0.062) | |||

| New jobs in creative sectors × human capital and education | −0.006 | ||

| (0.006) | |||

| New jobs in creative sectors × openness, tolerance, and trust | −0.010 | ||

| (0.015) | |||

| New jobs in creative sectors × local and intern. Connections | 0.001 | ||

| (0.011) | |||

| New jobs in creative sectors × quality of government | 0.001 | ||

| (0.011) | |||

| Human capital and education | −0.053 | 0.010 | 0.016 |

| (0.038) | (0.011) | (0.014) | |

| Openness, tolerance and trust | −0.017 | 0.129 *** | 0.097 ** |

| (0.062) | (0.037) | (0.043) | |

| Local and international connections | −1.698 | 1.011 | 1.061 |

| (4.927) | (6.621) | (7.638) | |

| Quality of government | −0.179 *** | −0.061 *** | −0.049 |

| (0.052) | (0.011) | (0.033) | |

| Time fixed effects | −0.070 *** | −0.073 *** | −0.067 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.007) | |

| Constant | 12.720 | 2.931 | 2.524 |

| (14.205) | (19.035) | (21.813) | |

| No. of observations | 372 | 372 | 372 |

| R-squared (within) | 0.905 | 0.900 | 0.894 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cerisola, S.; Panzera, E. Cultural and Creative Cities and Regional Economic Efficiency: Context Conditions as Catalyzers of Cultural Vibrancy and Creative Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7150. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137150

Cerisola S, Panzera E. Cultural and Creative Cities and Regional Economic Efficiency: Context Conditions as Catalyzers of Cultural Vibrancy and Creative Economy. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7150. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137150

Chicago/Turabian StyleCerisola, Silvia, and Elisa Panzera. 2021. "Cultural and Creative Cities and Regional Economic Efficiency: Context Conditions as Catalyzers of Cultural Vibrancy and Creative Economy" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7150. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137150

APA StyleCerisola, S., & Panzera, E. (2021). Cultural and Creative Cities and Regional Economic Efficiency: Context Conditions as Catalyzers of Cultural Vibrancy and Creative Economy. Sustainability, 13(13), 7150. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137150