A Cross-National Comparative Policy Analysis of the Blockchain Technology between the USA and China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Development of Blockchain Industrial Policies

2.1. The USA’s Blockchain Industry Policy

2.2. China’s Blockchain Industry Policy

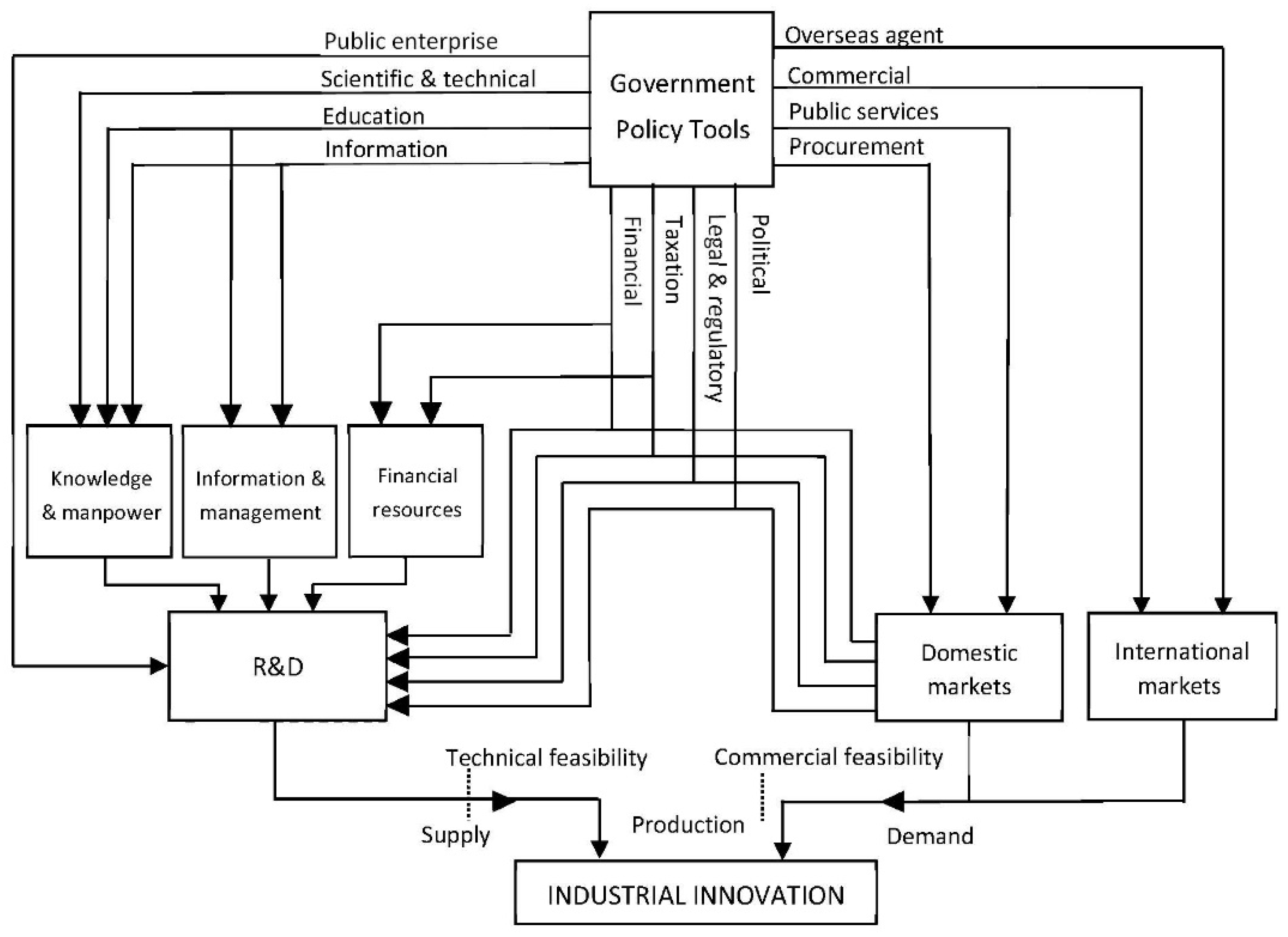

3. Innovative Policy Framework in Blockchain

4. Materials and Research Methodology

5. Results

5.1. The Policy Taxonomy of the USA

5.2. The Policy Taxonomy of China

5.3. Cross-National Policy Tools Comparison

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Findings and Discussion

- (1)

- Under Supply-side policy shown in Table 4, we can see that the Chinese authorities focus more attention than those in the USA. As shown in Table 2, the USA focuses on Public enterprise only and its specific policy activity is to implement blockchain for private medical data with portable and digitally secure ways. Clearly, the USA government has realized the potential of blockchain and has begun to implement it for many purposes.

- (2)

- Results in Environmental-side policy in Table 4 show that both governments place over 50% of their attention on this category. As shown in Table 2, the USA authorities tend to emphasize Legal and regulatory tools with the policy activities to regulate and license money transmitters, protect private property and contract integrity, conduct regulated research, take actions for securities registration issues and fraud and work towards cryptocurrencies and blockchains compliance standards such as NIST and HHS. In terms of Political policy activities, these comprise blockchain products complying with systems and regulators and for virtual currency businesses to file as money transmitters. Due to cryptocurrencies, ICOs and their exchanges face new regulatory challenges, resulting in new product cases for legislation to prevent violating the current regulatory framework in the USA.

- (3)

- In Demand-side policy, Table 4 shows that the USA authorities focus much more attention than those in China. As shown in Table 2, the USA tends to use Public services tools with policy activities to issue blockchain guidance documents, form working groups on securities regulation and taxation, investigate and define security regulation, use blockchain in health and research, coordinate the need for financial products and transactions through regulatory agencies and deter and prosecute fraud and abuse. In terms of Procurement, the policy activities include blockchain products complying with the current system and regulators, facilitation of a smarter energy grid with blockchain and development of encryption standards for medical data protection. The CFTC, SEC, federal and state regulators and criminal justice authorities work together to bring transparency and integrity to deter and prosecute fraud and abuse.

- (4)

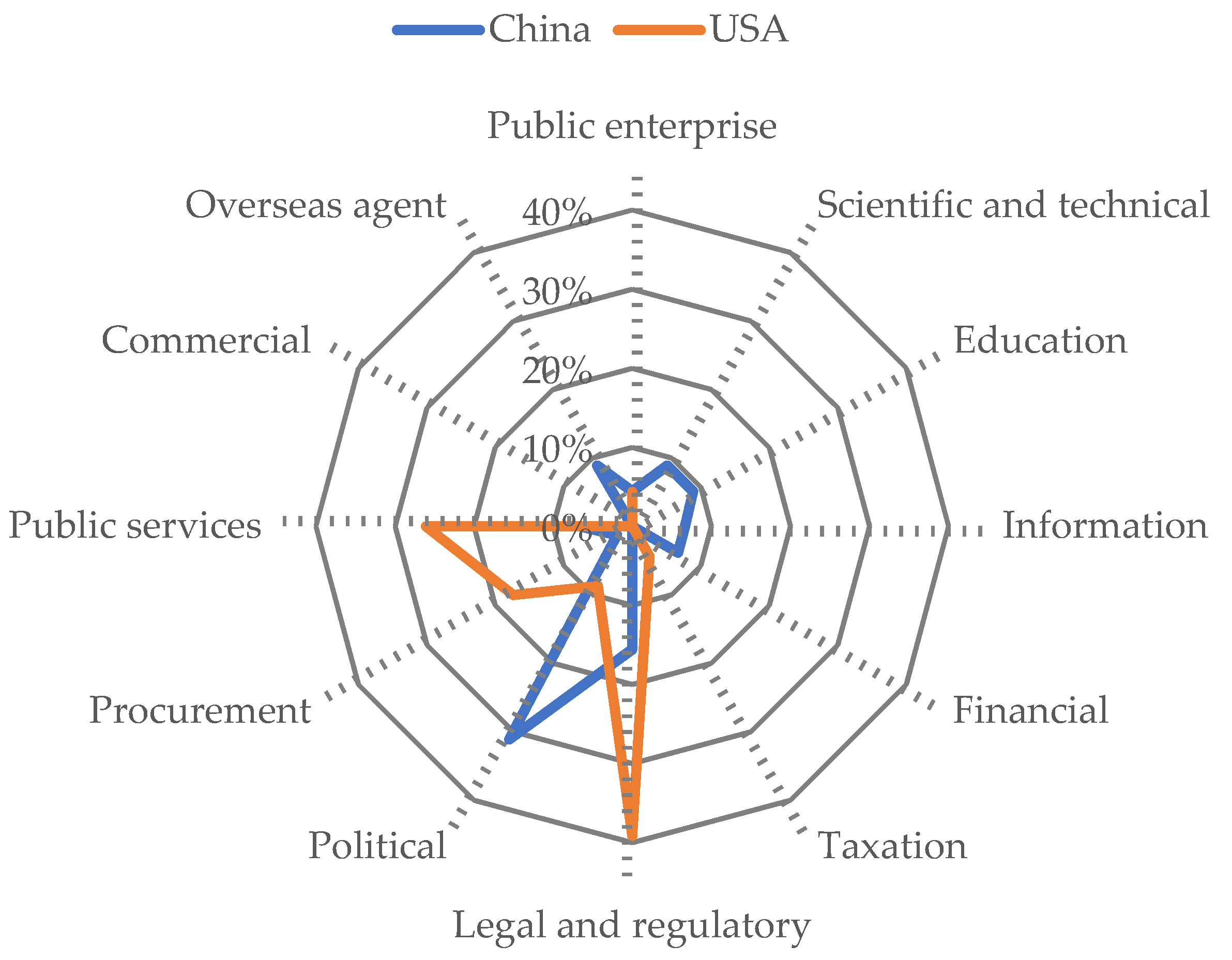

- In the USA, 52.1% of the innovative blockchain policy activities of the 2018 Joint Economic Report fall under Environmental-side policy category, as shown in Table 4, where the main policy tool is Legal and regulatory at 39.1%. Second, 43.5% of all policy tools are found in the Demand-side policy category and where most of the resources are allocated to Public services, at 26.1% and Procurement, at 17.4%. Finally, there is the Supply-side policy category with only 4.3% of activities, with Public enterprise as the only group of policy tools. Therefore, Legal and regulatory is seen to be the most important policy tool in the USA as shown in Table 5, followed by Public services, while Procurement ranks third. Since Legal and regulatory and Political are both in Environmental-side policy category, this category becomes the most important aspect of the USA government approach to blockchain. This analysis shows that the USA ignores the Scientific and technical, Education, Information service, Financial, Commercial and “Overseas agent” policy tools. It can be seen that in terms of policy, the USA focuses on maintaining a good market competition order and adopts measures to establish standards and create a good competitive environment under Environmental-side policy. On the Demand-side policy, through the provision of public services, blockchain technology can enjoy a friendly space. In addition, in which to develop. Finally, the very limited Supply-side policy is in line with the laissez-faire market principle of the USA.

- (5)

- In China, as shown in Table 4, the innovative blockchain policy activities laid out in the China Blockchain Technology and Application Development White Paper allocate most of the resources to Environmental-side policy category, at 53.3%, followed by Supply-side policy category with 28.9% and then Demand-side policy category with 17.8%. Of all the policy tools, Political tools account for the highest proportion, at 31.1%, as shown in Table 5, followed by Legal and regulatory with 15.6%, while Scientific and technical, Education and Overseas agency ranked third, each with 8.9%. It is found that China neglects the Taxation and Commercial policy tools. In terms of policy, it can be seen that China urgently needs to establish technical standards in the face of as-yet immature blockchain technology in industry. At the same time, China’s Political policy tools support private enterprises to organize industrial alliances, unite internal forces and demonstrate China’s ambition to become a leader in blockchain technology.

6.2. Conclusions

6.3. Practical Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- State of Blockchain q1 2016: Blockchain Funding Overtakes Bitcoin. Available online: http://www.coindesk.com/state-of-blockchain-q1-2016/ (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Global Charts: Bitcoin Market Capitalization. Available online: https://coinmarketcap.com/currencies/bitcoin/ (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution: Currency; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haitao, M.E.I.; IUJie, L. Industry present situation, existing problems and strategy suggestion of blockchain. Telecom. Sci. 2016, 32, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroglou, G.; Tsilidou, A.L. Further applications of the blockchain. In Proceeding of the 12th Student Conference on Managerial Science and Technology, Athens, Greece, 14 May 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, G.; Panayi, E.; Chapelle, A. Trends in cryptocurrencies and blockchain technologies: A monetary theory and regulation perspective. SSRN J. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, J. An IoT electric business model based on the protocol of bitcoin. In Proceedings of the 2015 18th International Conference on Intelligence in Next Generation Networks, Paris, France, 17–19 February 2015; pp. 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akins, B.W.; Chapman, J.L.; Gordon, J.M. A whole new world: Income tax considerations of the Bitcoin economy. Pittsbg. Tax Rev. 2014, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Noyes, C. Bitav: Fast anti-malware by distributed blockchain consensus and feedforward scanning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1601.01405. [Google Scholar]

- Sharples, M.; Domingue, J. The blockchain and kudos: A distributed system for educational record, reputation and reward, In Proceeding of the European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning. Lyon, France, 13–16 September 2016; pp. 490–496. [Google Scholar]

- Kosba, A.; Miller, A.; Shi, E.; Wen, Z.; Papamanthou, C. Hawk: The blockchain model of cryptography and privacy-preserving smart contracts. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 839–858. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, V.; Metcalf, D.; Hooper, M. The hyperledger project. In Blockchain Enabled Applications; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Enterprise Ethereum Alliance, About the EEA. Available online: https://entethalliance.org/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Launch of the International Association of Trusted Blockchain Applications—INATBA. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/launch-international-association-trusted-blockchain-applications-inatba (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- Boucher, P. How blockchain technology could change our lives: In-depth analysis. Eur. Parliam. Res. Serv. 2017, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Open Blockchain Platform, OwlChain. Available online: https://www.owlting.com/owlchain/?l=en (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Blockchain-Based Athletic Data Registry for Serious Athletes, BraveLog. Available online: https://bravelog.tw/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Blockchain Hotel Management Service, OwlNest. Available online: https://www.owlting.com/owlnest?l=tw (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E.; Oropallo, E. Surfing blockchain wave, or drowning? Shaping the future of distributed ledgers and decentralized technologies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 165, 120463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorkhali, A.; Li, L.; Shrestha, A. Blockchain: A literature review. J. Manag. Anal. 2020, 7, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, R.; Zegveld, W. Industrial Innovation and Public Policy: Preparing for the 1980s and the 1990; Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage of Nations: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Leyden, D.P.; Link, A.N. Government’s Role in Innovation; Kluwer: Norwell, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shyu, J.Z. Global Technology Policy and Business Operations; Hwa Tai Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H. From technological catch-up to innovation-based economic growth: South Korea and Taiwan compared. J. Dev. Stud. 2007, 43, 1084–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y. Development trend and application analysis of blockchain with 5G. Telecommun. Sci. 2020, 36, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. Problems and countermeasures in blockchain finance. Friends Account. 2017, 19, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gabison, G. Policy considerations for the blockchain technology public and private applications. SMU Sci. Technol. Law Rev. 2016, 19, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, M. Crypto-friendliness: Understanding blockchain public policy. J. Entrepreneurship Public Policy 2019, 9, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tencent Research Institute. White Paper on Blockchain Solutions: Building the Foundation of Trust in the Era of Digital Economy. Available online: https://www.hellobtc.com/d/file/201910/cd91a680d806ce1d7ac665b90f43bc04.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- 2019 Tencent Blockchain White Paper. Tencent Research Institute. Available online: https://www.hellobtc.com/kp/du/10/tengxunqukuailian.html (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Huang, R. Research on the supervision of financial blockchain technology. Acad. Forum 2016, 38, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Truby, J. Decarbonizing Bitcoin: Law and policy choices for reducing the energy consumption of Blockchain technologies and digital currencies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 44, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennock, M.J.W.; Cohn, A.; Butcher, J.R. Blockchain Technology and Regulatory Investigations. Pract. Law Litig. 2018, 2, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, D.W.; Berg, C.; Markey-Towler, B.; Novak, M.; Potts, J. Blockchain and the evolution of institutional technologies: Implications for innovation policy. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 103865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Blockchain Services Infrastructure. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/cefdigital/wiki/display/CEFDIGITAL/EBSI#:~:text=European%20Blockchain%20Partnership%20declaration,and%20maturity%20of%20today’s%20society (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- European Commission. Blockchain Technologies, Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/blockchain-technologies (accessed on 23 September 2020).

- The EU Blockchain Observatory and Forum, European Commission. Available online: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-521_en.htm (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- European Commission. Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on Markets in Crypto-Assets, and Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2020/EN/COM-2020-593-F1-EN-MAIN-PART-1.PDF (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, European Parliament. Report on Virtual Currencies. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2016-0168_EN.pdf?redirect (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Chiu, M.J.; Clarivate. Blockchain Technology Patents Mainly Layout Market. Available online: https://clarivate.com.tw/blog/2017/08/30/blockchain-technology-patent/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Report of the Joint Economic Committee, Congress of the United States. The 2018 Joint Economic Report. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/115/crpt/hrpt596/CRPT-115hrpt596.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2019).

- Musil, S.; California Governor Signs Bill Legalizing Bitcoin, Other Digital Currencies. A New Law Reverses Prohibition against Use of Anything but US Currency for Commerce. Available online: https://www.cnet.com/news/california-governor-signs-bill-legalizing-bitcoin-other-digital-currencies/ (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Section 107, CORPORATIONS CODE. California Legislative Information. Available online: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=CORP§ionNum=107 (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Cryptocurrency 2019 Legislation, National Conference of State Legislatures (NSCL). Available online: https://www.ncsl.org/research/financial-services-and-commerce/cryptocurrency-2019-legislation.aspx (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Castillo, M. Bitcoin Exchange Coinbase Receives New York BitLicense. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/bitcoin-exchange-coinbase-receives-bitlicense (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Aaron, S. The Trump Administration is Buying Into Blockchain Tech. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/the-trump-administration-is-buying-into-blockchain-tech (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Falkon, S. The Story of the DAO—Its History and Consequences. Available online: https://medium.com/swlh/the-story-of-the-dao-its-history-and-consequences-71e6a8a551ee (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- US Commodity Futures Trading Commission. CFTC Grants DCO Registration to LedgerX LLC. Available online: https://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/pr7592-17 (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Stanford CodeX Blockchain Group. 61 RegTrax Initiative. Available online: https://law.stanford.edu/codex-the-stanford-center-for-legal-informatics/about-regtrax/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- The Joint Economic Committee, United States Congress. Blockchain’s Medical Potential. Available online: https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2017/8/blockchain-s-medical-potential (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- BlockCypher and U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory. To Provide Blockchain Agnostic Distributed Energy Solution. Available online: http://www.prweb.com/releases/2018/01/prweb15117801.htm (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Made in China 2025, Key Technology Roadmap (2015 Edition). Available online: http://www.cae.cn/cae/html/files/2015-10/29/20151029105822561730637.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Lu, E.Y. Blockchain Patent: China Ranked First in Blockchain Patent Applications in 2017. Available online: https://www.blocktempo.com/china-filed-the-most-blockchain-patents-in-2017 (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Notice of the 13th Five-Year National Informationization Plan. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-12/27/content_5153411.htm (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- China Blockchain Technology and Industry Development Forum, Department of Information Technology and Software Services, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. China Blockchain Technology and Applications Development White Paper. 2016. Available online: http://www.cbdforum.cn/bcweb/index/article/rsr-6.html (accessed on 28 March 2019).

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology Information Center. China Blockchain Technology and Applications Development White Paper. 2018. Available online: http://www.miit.gov.cn/n1146290/n1146402/n1146445/c6180238/part/6180297.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- Mei, Z.; Kang, Y. The Application of BlockChain Technology in Financial Industry and Legal Consideration. J. Shanghai Lixin Univ. Account. Financ. 2017, 4, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- The Announcement on Preventing Token Issuance and Financing Risks. Available online: https://www.financialnews.com.cn/jg/dt/201709/t20170904_123977.html (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Gao, J.Y.; Business Next. Talking about Blockchain for the First Time, Xi Jinping: Innovation Is Always a Life of Nine Deaths. 31 May 2018. Available online: https://www.bnext.com.tw/article/49328/president-of-china-endorses-blockchain-technology (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- China Academy of Information and Communications. Blockchain White Paper. 2018. Available online: http://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/bps/201809/P020180905517892312190.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- China Academy of Information and Communications. Blockchain White Paper. 2019. Available online: http://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/bps/201911/P020191108365460712077.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- Rothwell, R.; Zegveld, W. An assessment of government innovation policies. Rev. Policy Res. 1984, 3, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, R.; Dodgson, M. Innovation and size of firm. In The Handbook of Industrial Innovation; Edward Elgar: Aldershot, UK, 1994; pp. 310–324. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C. The determinants of innovation: Market demand, technology, and the response to social problems. Futures 1979, 11, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.J.; Utterback, J.M.; Sirbu, M.A.; Ashford, N.A.; Hollomon, J.H. Government influence on the process of innovation in Europe and Japan. Res. Policy 1978, 7, 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.P. Basic Content Analysis; Sage: Newburt Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Briefing on the Use of Blockchain Technology for Defense Purposes: The Conference Report Accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2020. Available online: https://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20191209/CRPT-116hrpt333.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- POTENTIAL USES OF BLOCKCHAIN BY THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE. Value Technology Foundation. Available online: https://www.crowell.com/files/Potential-Uses-of-Blockchain-Technology-In-DoD.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- National Conference of State Legislatures (NSCL). Cryptocurrency 2020 Legislation. Available online: https://www.ncsl.org/research/financial-services-and-commerce/cryptocurrency-2020-legislation.aspx (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Comprehensive Interpretation “New Infrastructure” of China Development and Reform Commission-Blockchain Service Network (BSN). Available online: https://www.blocktempo.com/introduction-of-chinas-blockchain-service-network/ (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Policy Categories | Policy Tools | Policy Examples of Government Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Supply-side | Public enterprise | Innovation via publicly owned industries; establishing new industries; initiating new technologies adoption; taking part in private enterprise. |

| Scientific and technical | Joining research laboratories for scientific & technical development; assisting in research associations, learning societies and professional associations; grant fellowships in assistance of industrial innovation. | |

| Education | Education and training support at all levels, such as general education, universities, technical education, apprenticeship schemes, continuing or further education and retraining. | |

| Information service | Assisting in development of information networks and business centers, consultancy, advisor, libraries, cloud databases and liaison services. | |

| Environmental-side | Financial | Providing industrial innovation allowance, financial joint investment; offering loans for equipment, buildings or services, financial loan guarantee and export credit. |

| Taxation | Industrial innovation tax exemptions and exemptions for specific projects; research and development tax credits; indirect taxes and payroll taxes; and personal allowances. | |

| Legal and regulatory | Patents and intellectual property management; environmental and health regulatory control; monopoly regulations, supervision of social justice; certification management; awards, prizes and agreement standards. | |

| Political | Planning national innovation strategy; regional policy; innovation honor or awards; encouraging joint consortium merger; public consultation on policy development; legal and political system of investment. | |

| Demand-side | Procurement | Procurements and pacts from government; research & development agreements; technological prototype purchases. |

| Public services | Maintenance, supervision and innovation of health care services, public buildings, construction, transportation and telecommunications. | |

| Commercial | Currency regulation, tariff, trade agreement, commercial and commercialization of innovative industries. | |

| Overseas agent | Support innovation and development of international trade and transactions. |

| Policy Categories | Policy Tools | Policy Activity Description | Q’ty | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply-side | Public enterprise | Implement blockchains for private medical data (1). | 1 | 4.3 |

| Environmental-side | Taxation | Virtual currencies file as money transmitters (1). | 1 | 4.3 |

| Legal and regulatory | Regulate and license money transmitters (2); Protect private property and contract integrity (3); Conduct regulated research (2); Take actions for securities registration issues and fraud (1); Work towards cryptocurrency and blockchain compliance standards (1). | 9 | 39.1 | |

| Political | Blockchain products comply with system and regulators (1); Virtual currency businesses file as money transmitters (1). | 2 | 8.7 | |

| Demand-side | Procurement | Blockchain products comply with the current system and regulators (1); Facilitate a smarter energy grid using blockchain (2); Develop encryption standards for medical data protection (1); | 4 | 17.4 |

| Public services | Issue blockchain guidance documents (1); Form working groups on securities regulations, taxation (1); Investigate and define security regulation (1); Use blockchain in health and research (1); Regulatory agencies coordinate the need for financial products and transactions (1); Deter and prosecute fraud and abuse (1). | 6 | 26.1 |

| Policy Categories | Policy Tools | Policy Activity Description | Q’ty | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply-side | Public enterprise | Develop blockchain technology and applications (1); Establish blockchain research working group in financial sector (1). | 2 | 4.4 |

| Scientific and technicall | Use information technology to enhance digitalization (1); Combine blockchain systems and traditional business models (1); Formulate the requirements for the target system and the underlying technology platform (2); | 4 | 8.9 | |

| Education | Support key colleges and universities to set up blockchain professional courses (1); Promote the joint efforts of key enterprises and universities for blockchain talent training base (2); Strengthen blockchain professional and technical personnel for high-end talent training (1). | 4 | 8.9 | |

| Information service | Support demonstration bases and public service platform construction (2); Build blockchain open source community (1); | 3 | 6.7 | |

| Environmental-side | Financial | Financial support related to blockchain projects (1); Establish investment funds (1); Support the development of SMEs (1). | 3 | 6.7 |

| Legal and regulatory | Guide the formulation of specific standards (5); Standardize the comprehensive system listed in the framework (1); Relax market access restrictions (1). | 7 | 15.6 | |

| Political | Promote blockchain technology development and applications (1); Promote next-generation information technology (3); Establish blockchain standards system (4); Accelerate the development of international standards and reference architectures (3); Build a general development platform for blockchains (3). | 14 | 31.1 | |

| Demand-side | Procurement | Application standards support for government procurement (1). | 1 | 2.2 |

| Public services | Enhance the service to enterprises (1); Promote the scenarios of commercial, enterprise or financial application (1); Form blockchain ecology of technical exchanges and cooperation among enterprises (1). | 3 | 6.7 | |

| Overseas agent | Implement China-US and China-Europe mechanism to support enterprises (1); Lead/participate in blockchain international standardization organization (2); Establish blockchain standards for international community (1). | 4 | 8.9 |

| Policy Categories | Policy Tools | China | USA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q’ty | % | Q’ty | % | ||

| Supply-side | Public enterprise | 2 | 4.4 | 1 | 4.3 |

| Scientific and technical | 4 | 8.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Education | 4 | 8.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Information service | 3 | 6.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sub-total | 13 | 28.9 | 1 | 4.3 | |

| Environmental-side | Financial | 3 | 6.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Taxation | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.3 | |

| Legal and regulatory | 7 | 15.6 | 9 | 39.1 | |

| Political | 14 | 31.1 | 2 | 8.7 | |

| Sub-total | 24 | 53.3 | 12 | 52.2 | |

| Demand-side | Procurement | 1 | 2.2 | 4 | 17.4 |

| Public services | 3 | 6.7 | 6 | 26.1 | |

| Commercial | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Overseas agent | 4 | 8.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sub-total | 8 | 17.8 | 10 | 43.5 | |

| Total | 45 | 100 | 23 | 100 | |

| China | USA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Tool | Rank | Policy Tool | Rank | ||

| Political | 1 | 31.1% | Legal and regulatory | 1 | 39.1% |

| Legal and regulatory | 2 | 15.6% | Public services | 2 | 26.1% |

| Scientific and technical | 3 | 8.9% | Procurement | 3 | 17.4% |

| Education | 3 | 8.9% | Political | 4 | 8.7% |

| Overseas agent | 3 | 8.9% | Taxation | 5 | 4.4% |

| Information | 4 | 6.7% | Public enterprise | 5 | 4.4% |

| Financial | 4 | 6.7% | |||

| Public services | 4 | 6.7% | |||

| Public enterprise | 5 | 4.4% | |||

| Procurement | 6 | 2.2% | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuo, C.-C.; Shyu, J.Z. A Cross-National Comparative Policy Analysis of the Blockchain Technology between the USA and China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126893

Kuo C-C, Shyu JZ. A Cross-National Comparative Policy Analysis of the Blockchain Technology between the USA and China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126893

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuo, Chu-Chi, and Joseph Z. Shyu. 2021. "A Cross-National Comparative Policy Analysis of the Blockchain Technology between the USA and China" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126893

APA StyleKuo, C.-C., & Shyu, J. Z. (2021). A Cross-National Comparative Policy Analysis of the Blockchain Technology between the USA and China. Sustainability, 13(12), 6893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126893