1. Introduction

Every city is a complex and dynamic system. Urban settlements change their form over time, as has always happened in the past and still happens today (perhaps at an increasing speed). When approaching this kind of phenomenon, urban studies mostly focus on the starting morphology and on the final one, analyzing the difference between the two statuses [

1,

2]. In contrast, studying the dynamics of changes in urban form and the incremental metamorphoses/assemblages of urban elements and spaces—not only the starting and the final status, but also all of the phases between them—can make important contributions to operative urban studies that focus on urban generation and regeneration design processes, as well as decision support systems [

3,

4].

The “Transitional Morphologies” Joint Research Unit, which was established in 2008 between the Southeast University of Nanjing and Politecnico di Torino, researches strategies and methods used by human settlements to incrementally change and assemble buildings and spaces from one period to another, from one place to another, and from one culture to another.

The specific mission of the Joint Research Unit is to ground adaptive urban regeneration design processes by describing the states of urban morphologies and their historical causes (from the points of view of the economy or society, as well as their symbolic value) in Asia and in Europe, as well as in the Southern regions of the world.

In order to describe the role and the perspectives of “Transitional Morphologies” research program, this position paper will firstly define what “transition” means. Then, it will highlight the kinds of processes that drive urban change (either influenced by economic events or oriented by code settings). It will also explain how transitional forms and transitional processes can be mapped and how transitions can be read/described/represented in order to discover their logic. The results of these investigations will be explained through specific case studies. Eventually, this position paper will elaborate on the idea of setting up parametric protocols for urban transformations, which are useful for urban generation and regeneration through a community-based approach.

Setting up an agenda to investigate the potential of the concept of transitional morphologies for contributing to the comprehension and the regeneration of the city is the main goal of this position paper.

Adopting the paradigm of “transition” implies studying urban morphologies not as the result of a process, but as the process itself. This paradigm requires conceptual clarification and, at the same time, a description of a general framework of tools and actions that are necessary for carrying out transitional studies on the contemporary city.

Generally speaking, transition is a process through which a change from one state, stage, subject, or place to another state, stage, subject, or place happens. It comes from the Latin verb “transire”, which means “passing through”. This implies that between one state and another state, there is an intermediate step/phase in which the first state has already developed, but the final one has not yet been achieved [

5].

In physics, “transition phases” are recognized (and specifically named): the liquid-to-gas transition phase is known as “vaporization”, and the liquid-to-solid transition phase is known as “freezing”; in addition, the solid-to-liquid phase transition is known as “melting”, and the solid-to-gas phase transition is known as “sublimation”. However, most of the time, solids turn into gases only after an intermediate liquid state [

6].

There is a transitional paradigm that is well known in the political sciences that concerns the movement of the so-called developing countries towards the state of development. In addition, the sustainability transition concerns the global movement forward and achievement of shared ecological goals. In anthropological studies, the ecological transition is a topic that refers to the process by which humans incorporate nature into society. Even in these cases, greater attention is normally paid to the transition phases themselves and to the intermediate states, rather than to the final state. The transitional paradigm is effective in describing any kind of process and any way of being dynamic in a given phenomenon [

7].

Observing transitions implies considering invariants and permutations as parts of a given process. In the field of mathematics, an invariant is a property of a mathematical object (or of a class of mathematical objects) that remains unchanged after operations or transformations are applied to that object (or that class of objects). In the same field, a permutation of a set is an arrangement of its members into a sequence or linear order; if the set is already ordered, a permutation is a rearrangement of its elements (in fact, the word “permutation” also refers to the act or process of changing the linear order of an ordered set) [

8].

What must be considered is that permutation is a process that turns a given order (or an ordered set) into a new order; it is not an entropic pathway towards a chaotic system, but a way to find a new system that is capable of responding to different circumstances. From a transitional point of view, what is established (invariants) is the skeleton and the framework of a phenomenon, but only the permutations can show the secrets (rules and behaviors) of the dynamic actions of change in the context of that phenomenon [

9].

In the field of urban morphology, this means that if the role of the invariants is to describe the main structure of an urban question, the numerous variations induced by permutations due to several (social, economic, and climatic) factors drive and describe the transitional urban morphologies.

Urban morphology has been proven to have (at least in the Italian tradition of studies) a very important background in structuralism, which is a general theory of culture, as well as a methodology that was initially developed in linguistics and later transferred to many other fields that are related to anthropology: sociology, archaeology, history, and so on. One of the main ideas of structuralism argues that there are invariant, universal, and collective structures in human thinking, expressions, products, and behaviors that we can generally define as patterns [

10].

During the 1960s, because of the dominant role of the structuralist epistemology, even the city was treated as an instrument of communication filled with signs that are meaningful, universal, unconscious, and invariant structures [

11].

In

The Architecture of the City (1966), Aldo Rossi spoke about meaningful “permanencies’’, referring to urban elements that do not change over time: the streets overall, as well as the monuments and types of buildings (such as residential blocks) [

12]. This structuralist approach to the topic of urban morphology was strictly linked with the emerging debate about the historical centers of Italian cities. In this frame, the search for the existence of an ideal skeleton in urban forms led the debate to focus on the real and material constitutions of urban facts (instead of insisting on remaining at the socioeconomic level).

It was clear to the masters of Rossi’s thought, Saverio Muratori and Gianfranco Caniggia, that there are no invariants without permutations. Recognizing permanent elements in an urban scenario is generally useful in better understanding the dynamics of all of the other elements, which continuously change in shape, configuration, and location inside the map of a city.

In his historic typological study of Venice, Muratori [

13] compared the internal structure of architecture over different centuries, while Caniggia [

14] openly showed his interest in a morphogenetic approach, pleading for the genesis and the development of urban forms. As J.W.R. Whitehand [

15] remarked, “Caniggia is trying to enunciate principles whereby cities can be transformed: his formulations tend to be (…) abstract”. Focusing on the recognition of dynamic models of urban form, the development of urban elements over time, and the continuous changes in urban spaces implies reasoning through permutations rather than through invariants.

Furthermore, we cannot forget that the main goal of those studies was not urban analysis in itself, but urban design for urban restoration, reuse, and regeneration. Saverio Muratori gave his work on Venice (1960) the title “Studi per una operante storia urbana di Venezia” [

16], where the adjective/present participle “operante” is full of meaning; it qualifies his urban history of Venice and can be translated as “working”, “operational” [

17], or even “operative”, as it will be in the present paper in order to keep the semantic value of “working” and “operational” and to extend the Muratorian concept to any kind of urban study that is oriented toward regeneration design.

Transitional urban morphologies are operative conceptual instruments for investigating the urban forms of contemporary cities (in Asia, Europe, and the Global South) through their development throughout history up to their present reality and even for looking at their possible future configurations in possible urban design processes, which must also be considered and studied as (possible) permutations.

“Transitional morphologies” is an expression that came simultaneously from urbanism and paleontology. In urbanism, “cities in transition” is a way to describe the condition of contemporary cities, which are always in the process of changing into something different because of the changes caused by demographic indexes, the lack or improvement of infrastructures, and the role of innovative technologies [

18]. In paleontology, the expression “transitional morphologies” is a way to describe the sequence of the development of an animal in prehistoric times by reading through fossils; the missing links in any evolutionary morphological chain always represent a transitional question [

19].

2. Materials and Methods

The chosen investigative method is an empirical approach involving four case studies in order to test the application of concepts that are traditionally related to urban morphology studies to the analysis and prefiguration of urban transformation in the framework of the transitional paradigm.

The four case studies, which were chosen to address four strategic questions of contemporary urban regeneration (the role of the real estate market, the effectiveness of urban codes as drivers, the adaptive city, and the urban permutation process), are investigated with different methodologies corresponding to the specific dimensions of each question.

For the same reasons, the kinds of materials used in the investigation are different in each case study, ranging from urban and territorial surveys realized in the framework of ongoing PhD research to a literature review and diagrammatic representation of abstract processes.

The intermediate results presented in the framework of this position paper were obtained mainly through a process of abduction [

20]: starting from the exploration of a small number of case studies, by following non-deductive inferential logic, it is possible to formulate a general hypothesis that will be verified later. This abductive research methodology, which is carried out through the development of a hypothesis, is increasingly used in studies of urban phenomena that are carried out in the field of information sciences. On the basis of complex scenarios, its use is intended to provide useful tools for decisions in design-driven fields, such as architecture and urban regeneration [

21].

Therefore, this research began by asking the aforementioned strategic question of contemporary urban regeneration by applying actions that are traditionally carried out by urban morphology studies—mapping the urban fabric with time-related thresholds and representing urban permutations and invariants—to four specific case studies: Istanbul Firkitepe (Turkey), Rimini (Italy), Luanda (Angola), and a literature review on post-World War II urban morphology studies.

In the context of the “Transitional Morphologies” Joint Research Unit, these studies (which have not yet been published) can demonstrate—with their different and specific methods and starting materials, but with the same general framework of the transitional paradigm—their contributions to the generation of an agenda that addresses contemporary urban regeneration processes as transitional phenomena.

The four insights that are used as the starting point of the abduction process to set the general agenda are listed below, and their specific methodologies and research materials are explained separately:

Sorting the transitional steps of an urban morphology is an action that can describe the role of rapid market processes as an external factor that influences urban forms;

Setting urban codes that are capable of managing transitions is an action that is useful for describing the potential of resilient rules in driving processes;

Mapping urban assemblages is a necessary action that may help in understanding complex phenomena (providing clarity for what an adaptive city is);

Reading and representing urban permutations are actions that are strictly interconnected with the needs of a new generation of representative tools.

2.1. Istanbul Firkitepe (Turkey): Morphological and Economic Data Analyzed through the Overlapping of Cartographic Layers

The typo-morphological approach is a method for analyzing the transitional phases of a changing physical space in relation to its economic value; it was used to systematically sort morphological and economic data for a given time frame and for a given place in Firkitepe, a neighborhood in the Kadikoy district on the Asian side of Istanbul. It is one of the oldest squatted areas of the city but has now been invested in over almost a decade (2012–2021) of gentrification processes [

22].

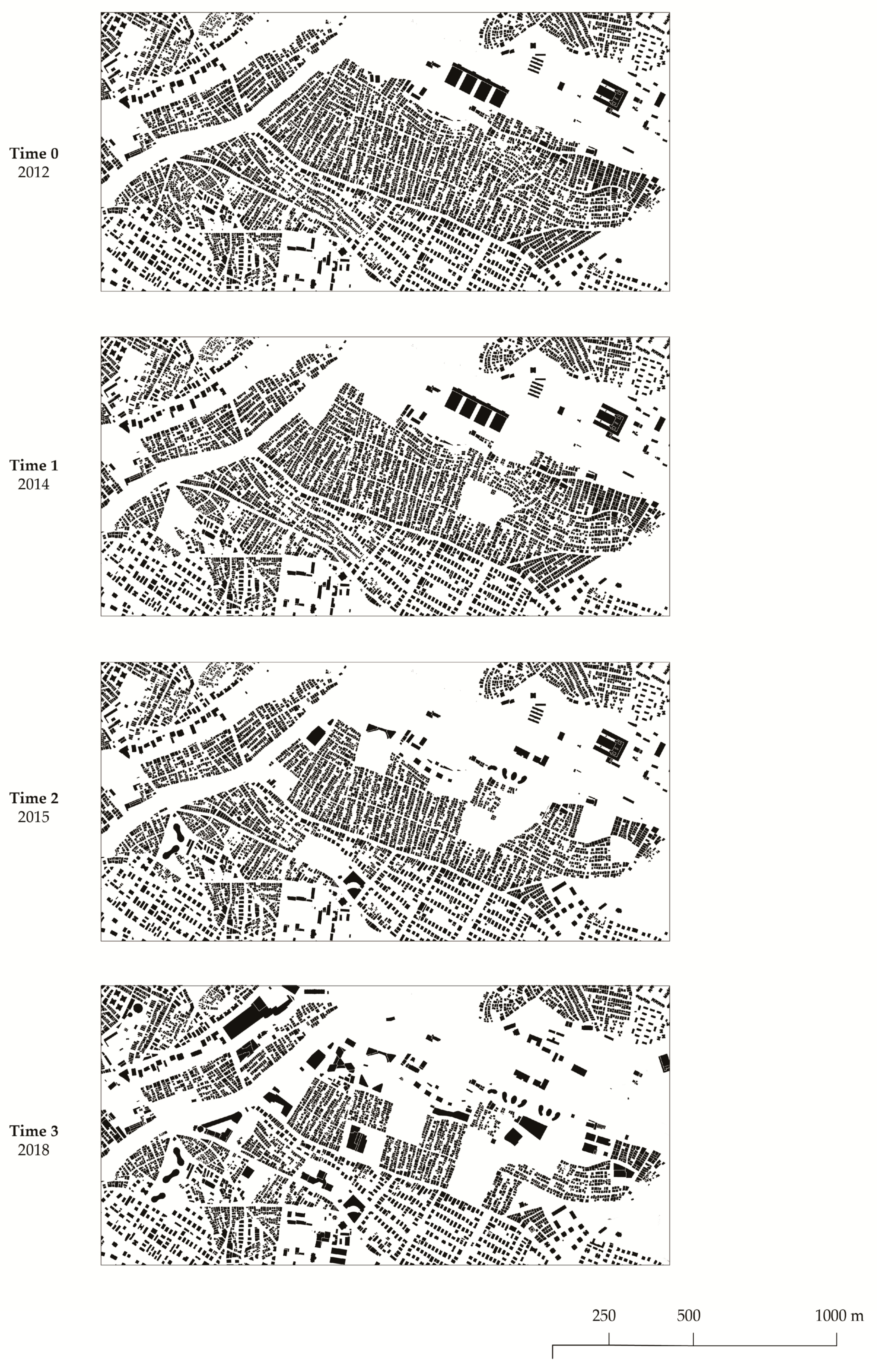

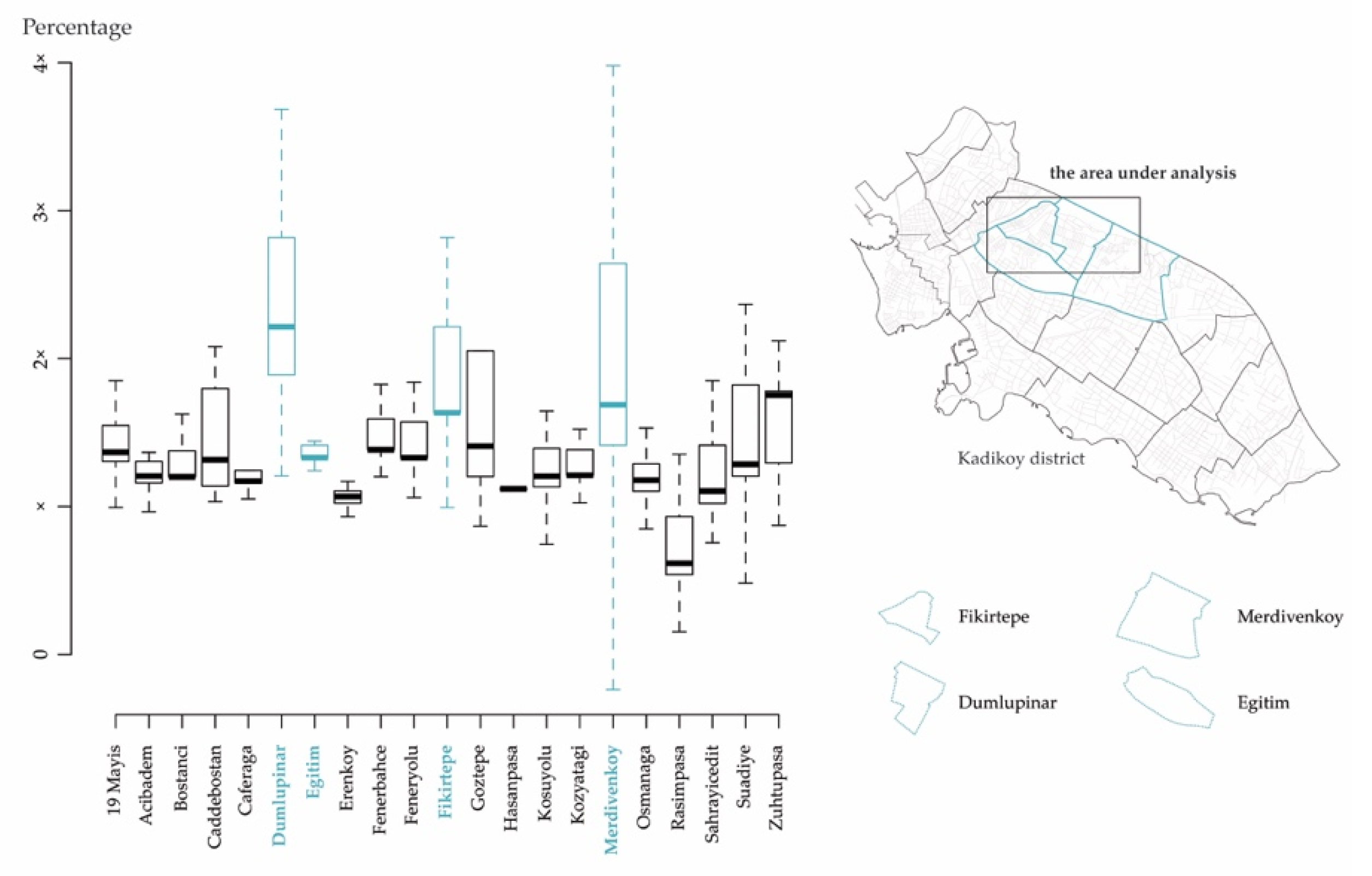

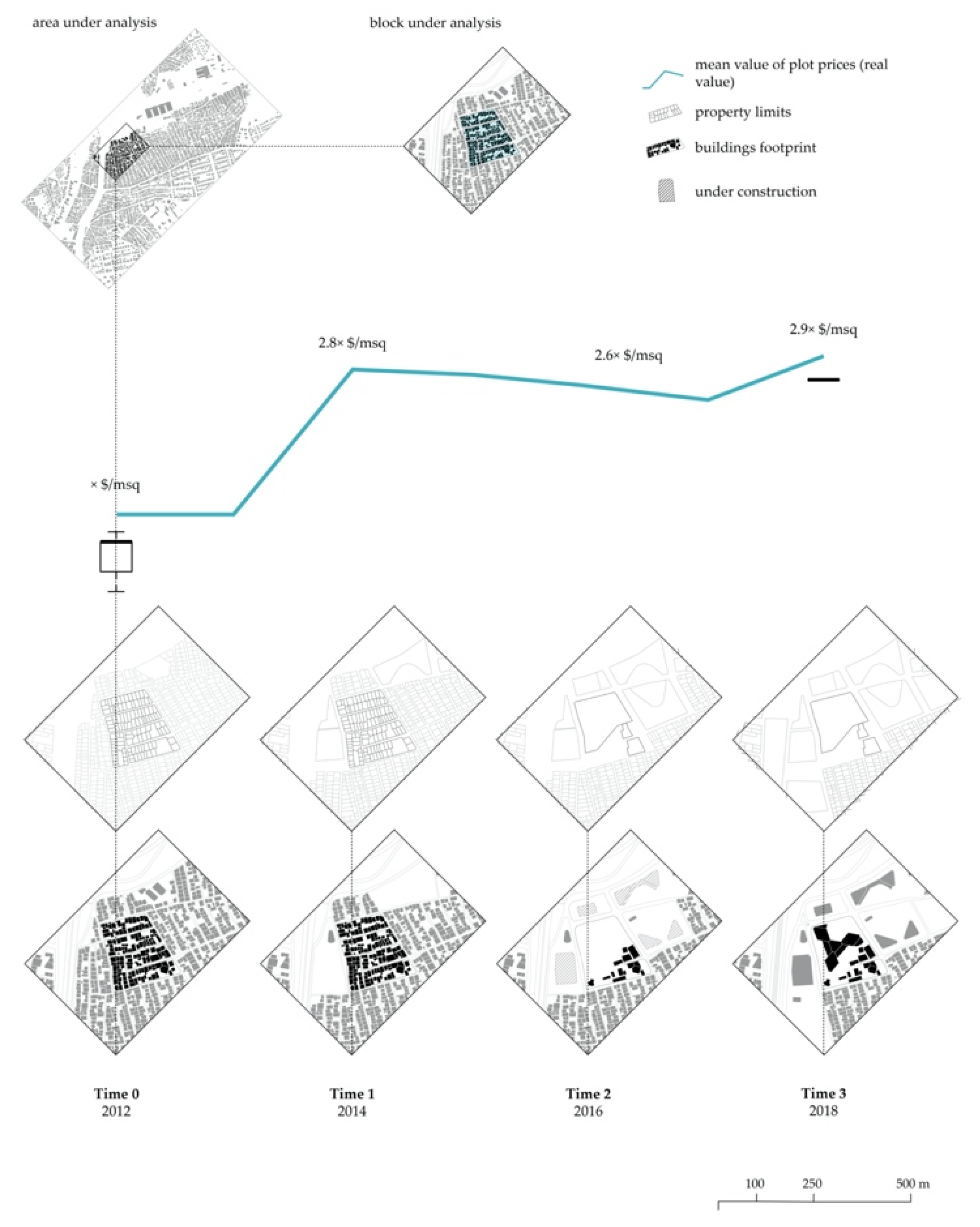

First, the changes in the built form and in the land prices for a given period of time were observed independently (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Next, the different categories of information were superimposed in chronological order and in biennial intervals for the length of time where the transformations occurred (

Figure 3). To construct the whole image, it was necessary to pay attention to a handful of details. First, capturing the widespread effects of meta-trends on the local built fabric is only possible through microscopic sampling. In this case, an urban block was taken as a molecular sample, and proper information on its main urban elements (streets, plots, and buildings) was distinguishably associated. Second, the data for an accurate local analysis at this scale are usually available from local data sources.

Even though morphological information can be extracted from available and open sources, accurate information on properties and prices must likely be obtained from field surveys or through data acquisition from local administration offices. In this case, morphological and economic data were acquired from the municipality’s records. Depending on their nature and geographical context, the acquired data will need to undergo a normalization and elaboration process. Third, all of the information collected must be reconstructed in chronological order, considering the significance of each layer.

To deal with the complexity of an area where evident transitions have been observed (as in Firkitepe), distinct categories must be identified and the relations between those aspects must have been previously clarified. Given the initial premises, the main categories suggested for this reading are strictly morphological and economic. The three layers can be defined as: the morphology as a form of material space [

1], a property as the form of a control [

23], and the land value as the monetary price of land [

24].

This method not only shows the interplay between increasing land values and transformations of urban forms, but it also highlights the processual nature that is possessed by the transforming urban morphologies. Sorting transitions into their steps helps to put permutations of elements in order, construct transdisciplinary relations, and see what comes before and after: What generates what, what is conditioned by the rest, and how does it all work?

2.2. Rimini (Italy): Historical and Archeological Maps to Inform Urban Coding

This case study analysis is based on the map used by Muratori to map the urban space (and time) of Venice, as well as the one used by Caniggia in Como; this analysis is used to develop a representation system whose main medium is the horizontal typological section. This method is based on the tradition of urban archaeological surveys (the maps of Rome from Giambattista Nolli to Rodolfo Lanciani), with their strong character of abstractness and their multi-scalar analytical approach. There is no interest in buildings’ heights in typological maps that show urban fabrics and urban patterns.

The aim of this methodology was to set up urban codes as implementations of urban plans. They are often seen as a complex system of prescriptions and maps that are different and complementary [

25]. As an operative instrument, an urban map has to point out the forecasts and indications relating to the structural contents of the settlements, services, and environmental system; these goals are pursued from a perspective of quantitative approximation, as well as in terms of representation.

The final goal of this experimental operation was to define a transitional-morphology-led urban coding in order to map urban space, map “urban time”, and adopt an overarching operative tool for new cartographies that is able to describe the forms of the so-called informal settlements and re-sort their contents by adopting innovative diagrammatic methods and by looking from the perspective of parametric morphological design.

The possible crossover between urban morphology and urban coding could be tested in the Italian historical centers, which present a compact urban fabric and many questions that have not yet been answered by urban planning. Here, morphological analysis is intertwined with the diachronic study of urban regulations in an experimental field. This case study, which focuses on the setting of a new urban transitional code for the historical center of Rimini (Italy), works on the formal classification of the urban fabric and the provision of rules that consider the formal urban evolution by using cartographic databases provided by the municipality—which commissioned the research—as well as archival documents and historical representations of the city’s core, the most important of which is embodied by the Gregorian Cadaster of 1811 (

Figure 4) [

26].

2.3. Luanda (Angola): Overlapping of Data at Different Scales to Spot the Variables

This mapping was realized by overlapping different forms of data: demographic, cartographic, and satellite imaging data. This overlapping allowed the coverage of different scales—from regions to blocks and to buildings—as well as of different time frames, in order to highlight the assemblages’ transitional character. In the mapping process, enclaves of urban assemblages were observed at different scales (urban scale and block scale) and in different time frames.

Luanda, the most populous city in Angola, presents both informal and formal morphological characteristics. The morphological analysis took the following variables into account: streets and their arrangement, formal or planned morphologies and their open spaces, and informal morphologies and their open spaces (

Figure 5) [

27]. The samples were observed on a smaller scale to analyze the informal sections’ changes over time; the aim of this approach [

28] was to recognize the morphogenic characteristics of the informal assemblages. For each sample, a multi-layered database that included building footprints, road networks, and boundaries was created (

Figure 6). The process was aided by the use of up to four aerial photographs at different intervals (ranging from 2000 to 2020) [

27].

In the long run, this type of mapping will be able to show the potential to create an atlas of samples, which may provide a better understanding of how these assemblages work in terms of their morphologies and adaptations. In this way, the morphology of an assemblage provides a consistent descriptive language for the built environment and facilitates comparison. As for the resultant maps’ role, they embody spatial knowledge, which is not replaceable by words or numbers [

29]. In this sense, mapping becomes a medium for combining information and visualizing it in order to understand complex situations in urban assemblages.

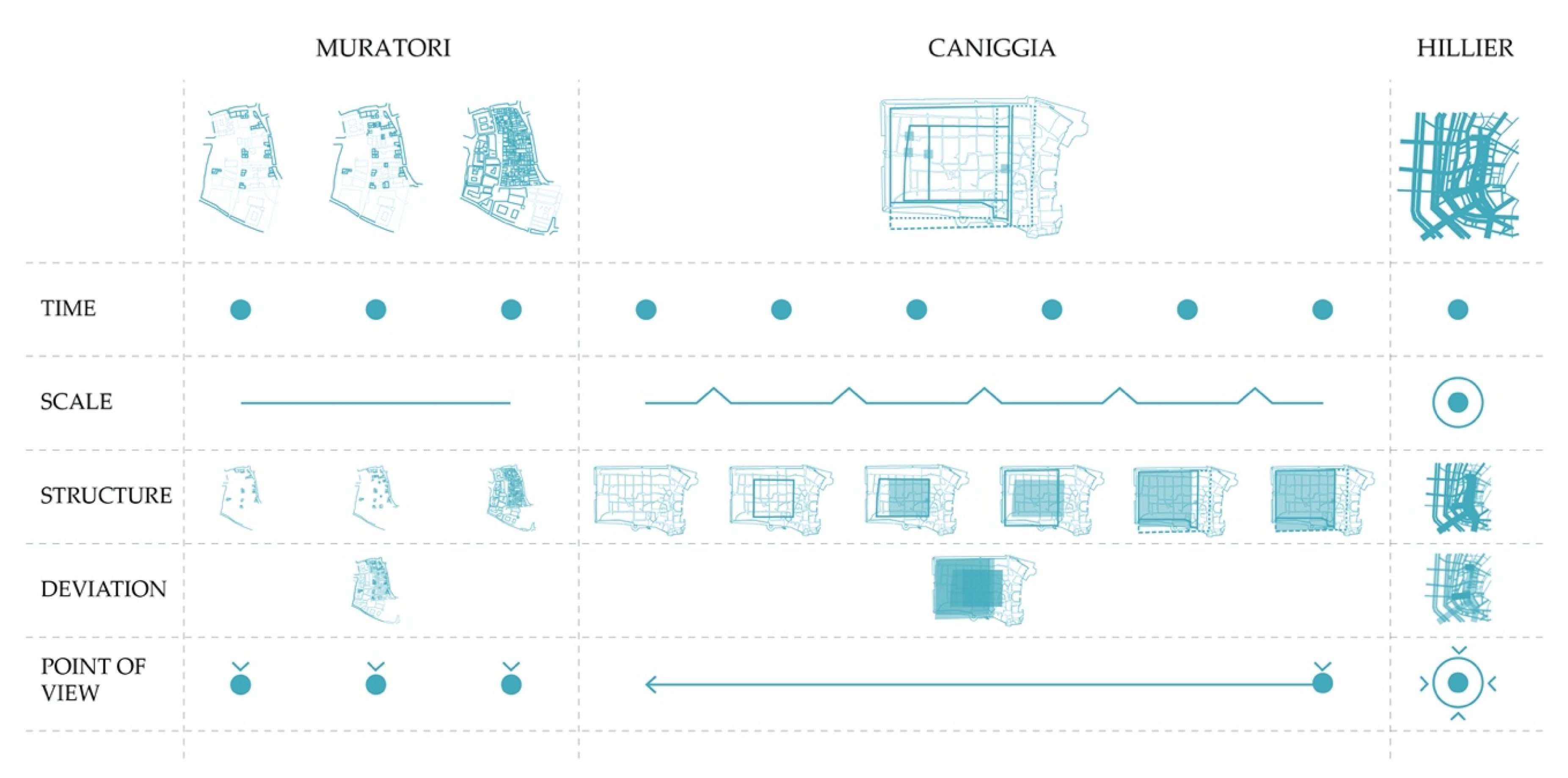

2.4. Muratori, Caniggia, and Hillier: A Literature Review to Highlight the Evolution of the Representation of Urban Form and the Diagrammatic Value in the Urban Permutation Process

As archival images that document states of knowledge, maps help us appreciate those who attempted to explore the same terrain in earlier epochs with less adequate measurement instruments [

30]. Even though the evolution shown by maps has multiple perspectives (which are based on different representations made by different people at different times), maps can be studied with the purpose of representing the overall complexity of transitional processes.

The use of maps made by Saverio Muratori and Gianfranco Caniggia followed the same principle as that described by Hall: an overlapping of different layers that define the evolution of a specific part of the city. Starting from the definition of the maps, the process of reading urban spaces developed by the Italian morphological school can be compared with the diagrammatic method. In the same way, Bernard Hillier—the founder of the Space Syntax theory—situated his analysis within the spatial evolution of specific urban settings and buildings. Here, the matter is a location within an existing spatial order that may be approached through a diagrammatic process that is closer to mapping than anything else. However, it is a kind of mapping that is oriented towards revealing the underlying structure, a mapping that becomes a vehicle for identifying underlying principles rather than for recording what has readily manifested.

A map provides orientation in an actual setting [

31]. The attention moves with it from a spatial reading of the urban frame’s existing conditions to a future perspective on changes inside the city in order to work with the permutations in urban resilience and adaptations of space. Diagrams are not only associated with the analysis of objects and the patterns projected onto them. As such, an operative method can be experienced as a continuous diagramming practice for representing diachronic and synchronic dynamicity.

The diagram became a vehicle that registers a process of becoming [

30], and for this reason, it is even able to read permutations in a more performative way. To understand how permutations can be read through a morphological study, one should start from the beginning of the analysis and address the elements deduced from typo-morphological maps—scale, space, time, structure, and deviation—which define the process of transition. The study of Venice by Muratori, the maps of Como by Caniggia, and Hillier’s analysis provide a starting point for a methodological analysis of the behavior of maps according to the study of urban morphology (

Figure 7).

All of the elements considered here give specificity to the method of reading cities, and they can be compared in the process of diagramming. Permutations, transformation processes, and evolutions are all characterized by a specific structure that can be identified to define multiple scenarios. Moreover, it is necessary to provide a recognizable pattern that is linkable to the urban shape [

32]. Implementing the diagrammatic method used by urban morphology schools to read urban patterns can shift the attention from a historical point of view to the perspective of the future.

3. Results

3.1. Sorting the Transitional Steps of Urban Morphologies (within Rapid Market Processes)

The complexity and dynamism of cities gave birth to a widespread tendency in urban studies: that of relating them to biological organisms [

33]. Their development, just like in biological entities, happens both in a slow, steady way—accomplished through small mutations—and quickly through periodic mutations caused by rapid environmental changes [

34,

35,

36].

Going beyond this transdisciplinary analogy, for studies that continue to view the city from an economic perspective, the pace of evolution of the urban form can be understood through the market forces that shape it [

37]. Usually, at the urban scale, because of the inertia of the existing local conditions—such as norms, property rights, communities, etc.—permutation processes take a long time, and the changes in the built fabric occur in a relatively slow way. On the other hand, if the discrepancies in the different economic values of the former and future uses are high enough to overcome those inertias, then rapid transitions that lead to drastic mutations in the urban fabric can occur [

38]. This is when the transformation of an obsolescent neighborhood becomes optimal.

One of the challenges of today is gaining intuition about these rapid changes that characterize contemporary times in order to find a way to read them with the most integrity.

As mentioned above, the idea of transitional forms (the missing links in the process chain) is used in paleontology to construct a complete record of a subject’s evolution [

39]. The intermediate phase is used to link the predator and the ancestor of the same species in order to seek hints of the factors of change. The main scholars that shaped the urban morphology studies used this concept to document the long-standing mutations in the built environment with respect to human life. Ten years after Muratori read Venice’s evolution over the centuries, M. R. G. Conzen, the founder of the British school of urban morphology, observed the evolution of space through multiple periodical time frames when analyzing Alnwick’s urban form [

15,

40].

Although these studies provide perfect evidence of the morphological evolution of the city with a longer and steadier pace, understanding the drastic transformations of contemporary spaces today requires a more tailored analysis, especially when explained by the creation high economic value (profit).

The implicit argument that has built up until this point is that, when described mono-dimensionally and perceived as a two-ended process (just the starting and the final statuses), urban morphology does not bring important factors of change into view—neither the idea of profitability (from an economic point of view, the main element that triggers the transformation process) nor the factor of time. From this point of view, morphologies are seen both as conditions under which inertias are created and outcomes of periodic changes (when those inertias themselves are overcome).

Moreover, it should be noted that the idea of profitability in urban transformation should not be exclusive to the contemporary world, through it is widespread and more essential than ever. Thus, it can no longer be neglected in accurate studies that address contemporary transformation processes. Hybrid methodologies that are encapsulated in a multi-level perspective that integrates different and independent disciplines can be a promising start.

3.2. Urban Coding in Transition: Rules and Processes

If the changes induced in urban morphologies by market factors happen in the way described above (slow and steady with sudden rapid metamorphoses), another kind of change in urban morphologies can be planned by adopting urban codes. While the market-driven changes follow a kind of biological development, the code-driven changes follow a rather deterministic evolution. However, the sets of formal rules (urban codes) that are governance tools for decision makers (as well as for generating and regenerating cities) can also have a close relationship due to the transitional urban morphology paradigm.

Today, cities show a typical combination of homogeneity—due to the history of their development—and diversity—induced by the application of rules. The diversity is framed by two specific kinds of order: One is due to urban plans, and the other is due to urban codes [

41]. In recent years, the significance of urban codes has been brought into sharp focus; they can be used either as instruments that are suitable for adaptive urban regeneration or as new tools for shaping the future [

42].

The development of a new generation of urban planning and design rules requires a deep and possibly critical understanding of three main factors: the origin of urban codes, their historical evolution, and their effects on the built environment. According to a positivistic—but still shared and alive—opinion, the manipulation of urban patterns, uses, and forms through rules substantially impacts the quality of inhabitants’ lives. The paradigm of social sustainability is currently being pursued in urban planning.

Nevertheless, on the other hand, the efficiency of urban codes can be improved by considering the results of urban form analysis. The urban morphological studies that were originally established by the Italian School between the 1960s and 1980s are able not only to read the evolution of the city, but also to become fundamental assets in the formulation and application of codes, especially when those codes have been proven to have a relevant formal background.

In order to renew the connection between the activities of urban morphological studies (by mapping urban realities) and urban coding (by establishing sets of rules), the approach of transitional morphologies requires the definition of three parameters: urban space, time (between description and prescription), and operative tools.

Even though urban mapping and urban coding are devoted to the same topic (generally speaking, urban space), they consider it differently. The Italian approach to urban morphology considers the city as a fact that can be described and classified by types, and a type is intended as a tool for investigating the city’s architectural artefacts and their dispositions/combinations [

13]. In contrast, traditional urban coding quantitatively investigates the space of the city. The advent of the modern Italian city led to the interpretation of space through national laws, starting from the urban planning law of 1942, which was based on the idea of zoning; describing cities as a patchwork of homogeneous areas with clear regulatory boundaries is the original abstraction suggested for urban-code-driven planning activities. As such abstractions are unable to treat differences and singularities, the zoning boundaries neglect a series of gray areas in which the urban plan no longer plans, and instead limits itself to regulating the use of the assigned building potentials [

43].

It is true that the Italian tradition of studying urban morphology considers the ancient city as the only object of study [

44]. From the 1970s on, from the perspective of the industrial city, heavy criticisms were made because of the difficulty of analyzing an expanding city’s urban fabric; the hardest criticisms concerned the absence of a precise relationship between known types and the built environment of the peripheries of the urban fabric, highlighting the lack of interpretative typological categories for the shapes of a city in transition.

Transitions happen over time, and the role of time in mapping the evolution of urban forms and in testing the efficiency of urban coding is the second main issue. Urban morphology considers time as a descriptive factor that lets us understand the shapes of things as they are in their historical becoming, so every new territory’s shape is a state of transition. Despite its great attention to urban history, the Italian approach to urban morphology also shows a strong predisposition towards urban projects that recognize the design constraints in historical analyses of urban studies: “studies for an operating urban history”.

Urban coding, on the on the other hand, assigns time a prescriptive value, viewing urban forms from a predictive perspective. Laws, rules, and norms show limited efficiency over time; they begin to produce their effects at a specific moment and cease to produce them at another. Nonetheless, the predictive nature of urban codes—implemented according to the planning instrument—is sometimes ineffective; plans do not clearly distinguish the rules and procedures from objectives, long-term choices, and short-term forecasts [

45].

That which can solve the aporia of the different considerations of urban space and urban time between urban morphology and urban planning—between mapping and coding—can be a primary and specific operative tool—cartography, which has been renovated in terms of the quantity and quality of its information, as will be explained in the following paragraphs.

There is a distinct advantage in combining “loose” analogical thinking and “strict” systematic thinking. Combining different kinds of descriptions provides a richer and more accessible body of knowledge [

46]. In addition, selecting the most compelling aspects for analyzing a city makes it possible to bring about an incisive change in the urban environment’s design, making it resilient.

3.3. Mapping Urban Assemblages (and the Adaptive City)

The approaches of urban coding and urban morphology (Muratori, Caniggia, and Conzen) [

13,

14,

40] help to frame the planning, urban development, and changes in developed regions with enduring and precise declinations of legal property. Nevertheless, a vast percentage of the rapid urbanization processes of today are happening in developing regions through informal settlements with processes that have ignored structured urban codes and rules. Contemporary urban conditions push towards adaptability in a context of increasing pressures, such as rapid urbanization and climate change. It is precisely in informal settlements that emblematic examples of adaptability and incremental development can be recognized [

47,

48,

49].

This phenomenon constitutes a great opportunity to study the transition from one formal state to another formal state in a framework in which the roles of the market and codes are less relevant in the face of the spatial and formal characteristics of the processes of urban generation and regeneration. This is an important verification of the paradigm of transitional morphologies itself.

Informal settlements represent complex adaptive assemblages that are dynamic and unpredictable; their self-organization patterns emerge with particular resilience and vulnerability levels [

31]. In an effort to go beyond the negative connotations that these assemblages have, observing their morphological characteristics and understanding their spatial patterns opens an opportunity to see potential in their incremental nature.

The results of mapping at the urban scale show an alternative to the non-existing official information from which some considerations can be made. Signs of evictions and relocations, signs of reclaimed land, and modifications due to important urban infrastructure projects can be found through a comparison of the samples’ morphologies. At the block scale, critical aspects of informal processes can be observed. Street layouts and plots do not appear before buildings, but they develop together. This incremental process of co-evolution makes the assemblages highly resilient and adaptable. Incrementality is recognized as a key characteristic of these assemblages and as a characteristic that could solve some of the problems linked to their seemingly chaotic nature in a step-by-step process of upgrading [

49].

“Assemblage” is a crucial concept in Deleuzian philosophy that has been adopted in many disciplines as a theoretical and methodological framework for exploring complexity: “The concept of an assemblage is commonly used to connote indeterminacy, emergence, becoming, processuality, turbulence and the sociomateriality of a phenomenon” [

50]. In this sense, the concept of assemblage works well when dealing with urban phenomena and their socio-spatial complexities. Rather than focusing on urban environments in their final state, assemblage theory is interested in emergence, processes, and multiple possibilities and temporalities. In other words, it plays an important role in better defining the transitional morphology paradigm and showing assemblages of urban spaces through their transitions and evolutions over time.

Because a tool for observing, measuring, and understanding assemblages is needed in many common urban process studies, mapping is a potential method for exploring complex urban assemblages, their processes, and their adaptability. Through mapping, the urban landscape can be decomposed into overlapping layers. In the context of the study of urban morphology, these layers could concern the morphology of the assemblages, but also the relationships among the different elements and agents that frame them [

51].

As useful as mapping is for the understanding of urban dynamics, there are many challenges to overcome when combining it with informal assemblages. By definition, informal settlements develop outside of a city’s formal gaze [

52], which means that they rarely appear in official maps. Existing data on informal assemblages are not available, accurate, or complete [

53,

54]. This lack of data represents a challenge that often complicates research on urbanization in developing countries. In addition, inaccurate data inhibit the efforts of agencies, city officials, and scholars to inform appropriate policies about such phenomena [

54].

Interfaces with maps and satellite imagery that are available online can potentially solve these issues and provide a source of up-to-date geographic and satellite information for studying informal assemblages and their changing morphologies. In this sense, Open Street maps, Google Maps, and Google Earth Pro represent widely accessible datasets that can be used across cases in mapping processes. Furthermore, the emergence and development of the Geographic Information System (GIS) allow digital technologies to display complex spatial datasets [

55]. Examples of automated methodologies for mapping areas of informal assemblages can be found in the academic realm [

53,

56,

57,

58]. However, GIS functions primarily on a geographic scale, and its use is less prevalent for morphological information. As a result, the mapping activity proposed here used a combination of remote sensing data and direct desktop mapping with available satellite photography in order to obtain the morphological maps.

3.4. Reading and Representing Urban Permutations

As a medium, mapping allows the representation of transitional morphologies and an understanding of how a city is made and how it mutates. If a study of urban morphology focuses on identifying how transitional characters can be distinguished within a city, it is necessary to combine the operative method (mapping) with any reading tools that are suitable for identifying sequences of patterns by starting from their matrices and logically reconstructing the intermediate state [

14].

The main aim of studying urban transitions over time is the discovery of the “laws of continuity within a transformation process” [

59]. In this sense, representing urban transitions implies the definition of a method of reading the transformation process inside a city, with mapping as an operative tool.

As mentioned above, morphological maps were first developed as a tool by Muratori and were later integrated with the typo-morphological approach on an architectural scale. By surveying and mapping, he identified a method for an organic study and superimposed his method of investigation on the city with a representation method [

13]. With an approach focused on understanding how a city changes—linking past and present—maps can be seen as diagrams that show the evolution of our collective thought about a specific spatial domain.

The operative method of the Italian School defines diagrammatic modeling principles that allow one to read single events in a city and connect them to create a complex system. While representing urban transition with an operative method is intended to read recurrences, identifying invariants and variations is intended to define a reading matrix in a permutation system [

60]. Its outcomes can be used for future generative approaches for urban patterns in the framework of responsive design [

61].

4. Discussion

The control of physiological factors (urban market) and artificial factors (urban code) that influence the transition from one urban configuration to another one, as well as the need to map (formal or informal) urban assemblages and the possibilities offered by maps when used as diagrams, requires the consideration of a generative approach, which would be useful for grasping the transitional character of urban transformations. Parametric strategies are often conceived as powerful tools for setting up semi-automations of recursive processes for the definition of design-responsive solutions. Today, they are specifically related to technical issues, such as actions aimed at mitigating problems with and adapting buildings and settlements to climate conditions; the role that urban morphology plays in resisting the effects of climate change is now widely recognized [

62], as are the indexes and parameters for measuring the impact of urban form as a factor for mitigation [

63].

In this framework, a meaningful example is the creation of a platform for data exchange between different types of software, which would constitute proof that the parametric approach is able to create generative models at the urban scale. Generative models are able to produce spatial solutions through processes of form finding that are controlled by designers, who can manage and redirect design workflows through successive feedback considering the conditions of changes in physical and socio-economic contexts with respect to climate change.

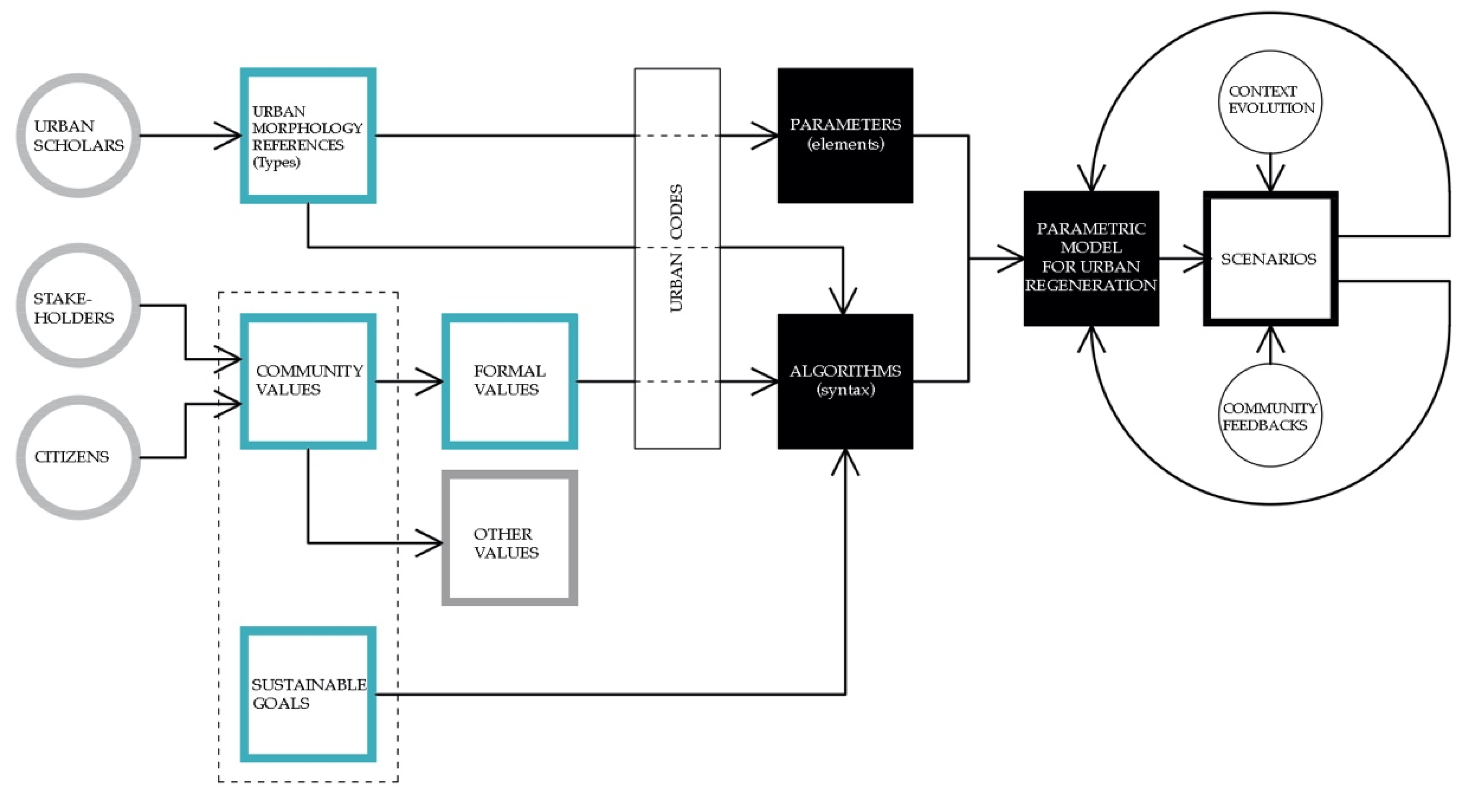

In order to upgrade parametric generative models for use in regeneration processes and to use them as a tool in the framework of participatory approaches to urban transformations, working on the relationship between values and parameters is essential. By considering urban morphology as the physical outcome of community values, we need to work on the translation of formal values (as morphological characters) into objective parameters by bridging the urban morphology and parametric approaches (

Figure 8).

A first step in this direction was made by Peeters and Etzion [

64], who automated the recognition of urban objects for urban morphological analysis. Their work also considered the analytical sides of the questions, but the recognition of elementary morphological entities and linking them to objective parameters is promising for the development of their research outcomes for generative work.

The next step towards the creation of generative models should consider the difference between the process of form finding and the concept of form shaping. The form-finding process, which was employed by Sergio Musmeci and Otto Frei at an architectural scale, keeps the form as something that exists previously to the design process, and its role is only to reveal the primigenial form, while the form-shaping process, as described in the theoretical work by Patrick Schumacher, describes the process of translation of the form into primary elements and the control of their mutual relationships. A form-finding process implies that an optimized configuration exists, and urban designers, whose role in this case is close to that of a demiurge, only need to reveal it by analyzing the forces (in a metaphorical sense) and determining its configuration. On the other hand, a form-shaping process implies a multiplicity of configurations in response to external stresses that come from a multiplicity of recognized stakeholders who act on the urban form as a decision-making question. Form shaping has been shown to be more likely to constitute a powerful tool for managing adaptive urban regeneration processes by considering the several opposing stresses that engender the transitional character of a city, which are established as a permanent starting condition.

5. Conclusions

The term “regeneration” is overused today, and a new definition of the term is needed not only to better describe urban transformations of declining areas or districts, but also, more importantly, to foster and drive them.

Even though the multidimensional concept of urban regeneration is still often confused with the mainly physical phenomenon of urban renewal [

65], the term “urban regeneration” traditionally refers, in the disciplinary literature, to area-based interventions—often publicly funded or supported—that aim to produce ongoing improvements in the social, economic, and physical conditions of places and communities that are experiencing aspects of decline [

66].

A new point of view introduced by McGuirk [

67] considers regeneration as an assemblage of processes centered on producing the above-mentioned improvements. In assemblage theory, assemblages (or relationships) are formed through the processes of coding, stratification, and territorialization; Deleuze and Guattari drew from dynamical systems theory, which explores the way that material systems self-organize, and they extended theory to include social, linguistic, and philosophical systems in order to create assemblage theory [

68]. From this perspective, it is possible to assume that an assemblage-theory-based approach enables a relational and multiplexed conception of regeneration that is subject to a range of relational effects and determinations to be created, rather than a strategic project driven by institutional designs from authoritative bodies. The relational ontology of an assemblage implies understanding of the urban condition as a constellation of elements configured into dynamic arrangements of relationships and arranged as “some form of provisional socio-spatial formation” [

69].

In this framework, regeneration might be considered as a complex process that is able to preserve memory and improve the physical and social dimensions of declining areas, but is also suitable for generating new values, grasping local changes and global dynamics, and considering the form of a city as provisional rather than defined—in one word: “transitional”.

Urban morphology, which is considered as a dynamic phenomenon and not as a final configuration, embodies and displays the transitional socio-spatial formation mentioned above. The first attempts to expand morphological analysis in terms of the dimensions involved, as well as in terms of the representation techniques involved in the analysis, are promising. The selected case studies worked as a sample to indicate that morphological representations can constitute a useful basis on which to structure the overlapping of data of different natures, such as economic, demographic, social, or climatic data, and describing their evolution while revealing the dynamic nature of urban phenomena. The same new representation techniques, such as algorithmic, parametric, and digital representations, can be used to further develop the potentialities of urban morphology studies for forecasting future urban forms. Finally, the diagrammatic nature of urban morphological representations makes them effective tools on which to ground urban codes that are able to foster urban regeneration by embedding flexibility and, therefore, ensuring the resiliency of the urban fabric.

After this exploratory phase, the establishment of a theoretical framework that describes operative methodologies for dealing with transitional urban morphology is the main challenge of the “Transitional Morphologies” Joint Research Unit, and it is strictly connected to the relationship between urban morphology and community values [

70], as well as to their translation into parameters that are able to support a new approach to urban regeneration (and generation) design based on community values in order to effectively become a decision-support system for urban policies.