1. Introduction

This paper illustrates the expressed and unexpressed potential that the adaptive reuse practices of (public) built cultural heritage and urban regeneration processes can have within local development and territorial cohesion strategies. The matter is investigated through the context of historic European spa towns: touristic territories that are currently dealing with the instability of their post-maturity phase, in which a decline or renewal is determined by the ability to (re)activate competitive and sustainable local dynamics [

1,

2].

At the turn of the 20th Century, spa towns represented a point of reference for the European cultural and political panorama. They embodied, since their foundation, urban and architectural experimentations that reflected the evolution of global tourism and health trends [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. First touristic destination in the modern sense, spa towns developed through a process of construction of the territory that originated from the identification of privileged locations across Europe—defined by the availability of natural resources (landscape, thermal water), geographical advantages (semi-peripheral location from main urban centres)—and a declared political will (initially aristocratic, then bourgeois) [

2,

3,

4,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Through acts of planning, physical, human and technological resources were transformed into territorial capital, interacting according to agglomerative and generative logics [

2,

10]. Spa towns also represent the result of a collective concept, generated and developed as a

manifesto of the emerging bourgeois in opposition to the unhealthy conditions of the industrial city [

4,

7,

11,

12]. Thanks to their integrated system of quality, where natural landscape, therapeutic gardens, public spaces, thermal baths and cultural buildings [

4,

7,

11,

12] complemented a prolific cultural environment, spa towns became gathering points and international exchange platforms for politicians, artists and intellectuals [

7,

13,

14].

During the 20th Century, multiple factors concurred to undermine the sustainability of these places. Beginning in the 1960s, when tourism became a mass phenomenon and mountain and seaside resorts emerged as competitive touristic destinations, spa towns gradually abandoned their ludic dimension in favour of health-related services and efficiency standards [

6,

7,

15]. Thermalism became a medical service supported by national health funds, and the architectural production of thermal baths started to follow hospital models [

6,

7]. Spa towns witnessed an exponential increase in their accommodation capacities [

7,

15,

16] and buildings for culture and entertainment began to struggle to maintain constant use [

7,

16]. Meanwhile, the growing affirmation of the contemporary medicine determined a split between the thermal system and the public health system, which eventually revoked its financial aid [

6]. The thermal sector dropped out of the market logics, affecting severely all levels of the local systems [

2,

6,

7]. Along with structural challenges, such as the collapse in touristic demand, unemployment and depopulation, and with the loss of cultural values, the repercussions of the crisis are still visible in the numerous episodes of the degradation and abandonment of public- and private-built cultural heritage [

6,

7,

16].

Today, spa towns have been recognised by the Council of Europe as European cultural landscapes (2010) [

17] and a group of eleven spa towns is currently in the UNESCO tentative list to become a transnational World Heritage Site [

18]. Nonetheless, while numerous policies addressed the relaunch of the local offer towards more integrated forms of tourism [

2,

19,

20,

21], many spa towns still struggle to find a renewed economic, social and cultural balance based on thermalism and tourism activities [

22,

23] and the issue of abandoned or underused built cultural heritage remains a key concern within the contemporary European debate [

24,

25,

26].

The profound changes in the socio-economic conditions that favoured the birth and development of spa towns suggest that, today, the role of these cities within the contemporary territorial dynamics could be revisited. As territorial product and a local project [

27,

28], spa towns are considered a depository of tangible and intangible resources. In a ‘fully circular’ logic, such resources represent the cultural and physical infrastructures and the latent opportunities that, recombined, can contribute to the innovation of territorial relations towards a sustainability transition [

29,

30].

The research presented in this paper argues that spa towns, as contexts of high urban and landscape quality, rich in cultural and architectural heritage, may assume a relevant role within local development and territorial rebalancing dynamics. This hypothesis assumes primary importance within the contemporary debate that advocates a renewed approach to the city and the territory, in search of new urbanities [

31]. Small- and medium-sized historic settlements, and therefore spa towns, can be interpreted as strategic fields for territorial development [

32]: fundamental resources to improve urban and environmental qualities; opportunities to rethink the ways of living, working and gathering; and potential laboratories of social experimentations and ambassadors of new development models [

33,

34]. Likewise, the underused or abandoned built cultural heritage can be reframed and transformed from an environmental, social and economic cost into an opportunity space. With the aim of re-proposing spa towns as laboratories of social, urban and architectural experimentations, their heritage represents a potential field of action, a critical mass able to catalyse local and territorial innovations and to support regional growth, unlocking new forms of stakeholder cooperation and funding potentials.

2. Methodology: A Systemic Approach between Theory and Practice

According to the territorial approach to local development encouraged by the European Commission and ‘borrowed’ from geographic studies [

35,

36,

37], the research shifts the focus from the main economic sector of reference—thermalism and thermal tourism—to the built environment. Spa towns are considered complex and dynamic systems, in their material and immaterial structures, as a result of the interactions between the subjects and the potential and actual processes activated on the territory. From the hypothesis that identifies spa towns as strategic fields for territorial development, the research revolves around the following questions:

What is the role of spa towns in their territories? How can spa towns contribute to the strengthening of the territorial capital?

How can the abandoned built cultural heritage related to thermalism contribute to renewed mechanisms of sustainable local development?

How can the multiple interests acting on the territory interact and cooperate? Which tools can support an integrated and multi-level approach to urban transformation?

The methodology adopted has been characterised by an interpretative and explorative approach and aims to provide a comprehensive and systemic vision of the topic. Secondary sources have been supported by a critical analysis of grey literature documentation, interviews and place-based research.

Section 3 presents the theoretical framework that illustrates the connection between cultural heritage and Sustainable Development strategies, framing adaptive reuse and urban regeneration processes as tools to address heritage and non-heritage goals. The section highlights the necessity to address adaptive reuse processes, urban regeneration and territorial strategies as an integrated challenge, considering the built environment as a living heritage and overcoming the divisions between conservation and urban management and development. This section also highlights how an integrated approach to adaptive reuse and urban transformations can unlock multi-level synergies and spillover effects.

Section 4 and

Section 5 present the investigation conducted on European case studies. Through the results of policies analysis and interviews with public administration practitioners,

Section 4 presents the key themes that emerge from contemporary urban regeneration and territorial development trends of three historic spa towns characterised at the same time by heritage-led processes and a strategic approach to urban transformations (Bath, United Kingdom; Baden-Baden, Germany; Vichy, France).

Through place-based research,

Section 5 narrows the focus to the Italian context and on how spa towns can contribute to territorial cohesion strategies. This section also stresses how the synergies created within urban transformation processes can broaden the funding possibilities in support of public administrations for implementing adaptive reuse and urban regeneration processes.

Section 6 illustrates the themes, tools and cultural conditions that have emerged as potential factors that foster innovation, providing a reference framework that has been organised into a set of recommendations. While referring to a few specific themes related to Italian spa towns, these recommendations come from and address the broader European context, and they provide valuable insights for cultural institutions, public administrations practitioners and policymakers operating in the field.

3. Abandoned Built Cultural Heritage as a Driver for Regional Growth

Since the 1998

Stockholm Conference on Cultural Policies for Development, the role of cultural heritage within the Sustainable Development discourse has gradually shifted from protection and safeguarding issues to a proactive role in building vibrant and creative urban economies [

38,

39,

40].

Today, cultural heritage is recognised as the fourth pillar of Sustainable Development, a strategic resource able to enrich territories’ social capital, contributing to cross-cutting EU policies such as job creation, rural, regional and local development [

41,

42,

43]. The New Urban Agenda (2016) emphasises the same potential on built cultural heritage and cultural landscapes and identifies their valorisation as a contribution to making cities more inclusive, resilient, sustainable [

44].

Well-known international best practices—such as the region-wide intervention for the recovery of historic buildings in the Halland region (Sweden), known as the Halland Model [

45]—have illustrated how the conservation of built cultural heritage can contribute to regional growth and Sustainable Development, when integrated into cross-sectoral multi-problem approaches. Through horizontal integration of different fields and actors, conservation projects have helped to unfold long-lasting social, cultural, environmental and economic values, producing positive externalities and spillover effects in non-heritage fields [

45].

Today, similar logics of value creation can be applied to adaptive reuse processes of built cultural heritage and to the transformation of cultural urban landscapes within a coevolutionary approach to the city and its territory [

39,

46,

47]. Product of past and present dynamics, these living systems necessarily imply change as part of their evolution.

As introduced by the UNESCO recommendations on the Historic Urban Landscape (2011) and stressed out by Bandarin and van Oers (2012), the need is to go beyond architectural and urban conservation by reframing the matter of heritage transformation within urban development issues [

48,

49]. When considered from a system-wide cultural district perspective, implying the horizontal and vertical integration of sectors, skills and interests, built cultural heritage can be considered as a cultural and physical infrastructure able to meet heritage and non-heritage demands [

50,

51]. It is a shift from the act of protection to a system of pro-action [

39], where adaptive reuse and urban transformation processes could be functional to strengthening local and regional development priorities; where the intervention or the investments on heritage do not depend or derive only from heritage values but, in a demand-driven logic, address competitive growth strategies [

39,

47]. Furthermore, while regional specialisation strategies promoted by the European Union still do not expressly address heritage as a strategic development sector, the awareness of the positive externalities deriving from the valorisation of built cultural heritage could contribute to intercept non-heritage funding opportunities for the implementation of adaptive reuse and urban transformation projects [

52].

This framework implies the cooperation between different interests, actors and sectors as it involves cultural, social, institutional and economic–productive matters, as well as public and private actors for the management of the common good: a continuous interaction which inevitably generates conflict [

45,

53]. In literature, the overcoming of such conflict has been defined by Gustafsson (2008) as

trading zone: an active arena within the decision-making process, where ‘conflict’ assumes a positive meaning and dialogue, mutual learning, synergic relationships and coordination of resources create a continuous learning process able impact on the local systems of knowledge and value production [

45].

Interventions on built cultural heritage and cultural (urban) landscapes can hence be intended as drivers for development models based on circularisation processes, applied not on sectorial fields but on the city and the territory as a whole, in their cultural, social, economic and environmental system, their governance and their transformation dynamics [

46,

53].

4. Spa Towns, Heritage and Strategic Planning: Experiences from the European Scenario

4.1. Strategic Planning: A Space-Time Synthesis of Places, Actors and Goals

The considerations about the role that cultural heritage can play within Sustainable Development dynamics—as well as the integrated approaches promoted for the valorisation of the cultural landscapes—can be related to the broader European context of a renewed territorial approach to the built environment, its valorisation and, therefore, to the evolution of the urban planning tools.

Within the logics of territorial development, non-linear and unpredictable development processes deal with a degree of uncertainty that demands to overcome the static nature of traditional spatial planning tools [

54,

55]. The strategic connotation of Sustainable Development plans has been encouraged since the early 2000s [

56,

57] and strengthened within the framework of the New Urban Agenda (2016), which supports the adoption of urban and territorial planning tools that address territorial governance through an integrated and long-term approach [

58]. According to the most recent recommendation of the European Commission, strategic planning is identified as a fundamental tool for Sustainable Urban Development [

59,

60] and defined as an adaptive process able to deal with ‘wicked planning problems’ deriving from the multiplicity of actors, scales, timeframes and interests involved in the process [

55]. Similarly to the heritage discourse, the concept of

trading zone has been applied by Balducci and Mäntysalo (2013) to urban transformations, identifying in the strategic urban plan a platform able to synthesise the different interests and objectives on the infrastructure of the city [

61,

62].

Therefore, strategic planning can be considered as a potential tool to support traditional and statutory spatial planning in overcoming the gap between heritage valorisation and local development processes and scopes. As such, within the research, the strategic dimension of the urban plan was considered as the most suitable to highlight current trends and investigate tomorrow’s scenarios of European spa towns: a common language to explore different social, economic, administrative scenarios.

4.2. European Trends: An Exploratory Overview

To investigate the current relationship between spa towns and their territory, their different development strategies, and to find out if and how spa towns are integrating cultural heritage valorisation and adaptive reuse practices into their local or territorial development strategies, the research proposes a comparative study of three spa towns belonging to different European contexts. The research focused on three spa towns that—since the 2000s—have been recognised as best practices in terms of urban regeneration [

24], and that in recent years have undertaken urban and territorial development processes characterised by a strong strategic component while, at the same time, being in the UNESCO tentative list for becoming World Heritage Site [

18]: Bath (UK), Baden-Baden (DE) and Vichy (FR).

In the awareness that strategic plans can imply different spatial and regulatory ‘translations’ depending on their design process or on their relation with statutory and non-statutory planning tools, the investigation assumes an exploratory nature. The three cases studies have been considered paradigmatic examples able to provide a valuable contribution to framing the research questions from a ‘thematic’ perspective. To understand the evolution of these cities over time, the investigation focused on both concluded and ongoing processes.

This investigation was based on literature, policy analysis and interviews with Public Administration practitioners involved in heritage valorisation (including the UNESCO application) and urban planning policies. The analysis was organised starting from the following questions:

Which phases characterised the development of the city in the 20th Century?

Which have been the main interventions on the architectural heritage? What role did the abandoned built heritage linked to thermalism play?

Under which conditions did the strategic plan develop?

Which are the main challenges and issues the plan wants to address?

Which is the role of the spa town within the vision for the development of the territory?

Which is the output of the strategic planning process? (Does the strategy remain a policy document, or is it translated into a spatial strategy? For the territory or the city?)

How does the strategic plan interface with the statutory planning tools?

How does the strategic plan interface with the various public and private actors and, in particular, with citizens?

How is the plan related to the concept of living heritage? How is the theme of the valorisation of the urban cultural landscape tackled?

Do specific projects characterise the plan?

4.2.1. Bath

In Bath, the massive industrial and uncontrolled development of residential construction during the 1960s, and the closure of the major thermal baths at the end of the 1970s, led to a period of severe economic crisis [

63]. The city reacted with a series of projects focused on restoring its historic centre, with the aim of relaunching the image of Bath as a spa town and promoting its cultural tourism [

64]. Subsequently, in 1987 Bath was recognised as an UNESCO World Heritage Site and, in 2007, the city promoted the development of a major urban regeneration plan that allowed the reopening of the historic thermal baths. This project was delivered thanks to a public–private partnership between the Bath and North-East Somerset (BANES) Council, Heritage Lottery Fund, Millennium Commission and Thermae Development Company. The Heritage Lottery Fund investment, dedicated to the reopening of the thermal baths, contributed to the creation of 600 direct and indirect jobs alone [

65]. The 2007 regeneration plan was part of a city-wide vision illustrated in

Future for Bath (2006), a document with the objective of identifying the city’s DNA and the guidelines for its economic redevelopment [

66].

In the same period, the Localism Act (2011) reorganised the urban planning tools, fostering a multi-scale flexible approach to land management. Urban and territorial transformations are now envisioned and regulated by the Core Strategy, which outlines general principles for the whole district, and the Placemaking Plan, which indicates priorities and strategic axes on a local scale. With the adoption of the district-wide Core Strategy (2014) [

67] and the local Placemaking Plan (2017) [

68], the city of Bath looks to the horizon of 2029.

Within the wider vision for the BANES district as an entrepreneurial place devoted to social inclusion and wellbeing, Bath’s spatial strategy revolves around five pillars—water and wellbeing, knowledge and invention, imagination and design, pleasure and culture, and living heritage [

68] (p. 5)—and derives from the awareness that tourism alone cannot provide a long-term, sustainable economic platform [

66] (p. 8). This strategy aims at creating a resilient local economy, based on diversification and local relations, to promote a city ‘where world class academia, high tech manufacturing, creative industries and training academies meet to develop new ideas that lead to job growth’ [

69] (p. 1).

By combining this objective with the willingness to enhance Bath’s historic landscape, the abandoned buildings of the Ministry of Defence and area of the Western Riverside have been individuated as ideal places for intervention [

68]. This vision, developed in cooperation with the West of England Combined Authorities, has been translated into the

Western Riverside Masterplan, a key area in the hearth of the city dedicated to the development of new economic sectors of reference: creative groups interested in reinforcing Bath’s image of a ‘beautifully inventive’ city [

70,

71].

4.2.2. Baden-Baden

In Baden-Baden, as in Bath, the consumption dynamics of the 1960s had a major impact on the historic town: the demolition of historic buildings in favour of commercial ones and the growing traffic problems in the city centre directly affected the city’s image [

72]. These dynamics had such a profound impact that in 1974 the Municipality of Baden-Baden promoted the

Town and Spa Development Plan (

Stadt- und Kurortentwicklungsplan), a first step towards a comprehensive plan for the city. It aimed to recover the town’s identity as a unique urban landscape deeply linked to its rural context and strongly focused on the recovery and on the conservation of the built heritage related to thermalism [

72,

73]. The plan promoted the construction of new hotels and cultural buildings, the redevelopment of the historic city centre and its public spaces (such the redesign of

Augustplatz, and the establishment of the pedestrian zone in the historic city centre), the refurbishment of the existing thermal heritage as well as the new construction of the

Caracalla Therme.

Since 2011, this approach has developed into strategic plans that complement the traditional planning tools:

Baden-Baden Entwicklungsplan (EP) 2020 and 2030 [

74,

75]. While they are not binding, these strategic plans incorporate the will of the Public Administration to innovate urban planning processes. The EP 2020 is articulated around nine principles for urban development (then maintained and extended by EP 2030) and eleven fields of action, further defined by specific objectives. These, when possible, are translated into thematic maps. The plans are also characterised by a high level of community engagement. EP 2020 was drafted through an open process in which the local council (

Gemeinderat) and citizens discussed the key issues: traffic and environment, demographic change, social infrastructure and education, city image and urban quality, the future of the spa town, the relationship between residents and tourists, family life, valorisation of the rural districts and digitisation. Private actors also supported the process as moderators or technical experts on specific issues.

To enhance the city’s touristic specialisation, create an inclusive social structure and attract young families, Baden-Baden promotes a renovated image of its therapeutic urban and natural landscape. While also referring to the recent UNESCO application (2014) [

18], the EP 2030 strengthens the role of urban quality and city image as crucial assets to promote a liveable environment. Here, thermalism is a cultural, architectural and environmental quality as necessary as a vibrant, diversified economy. Within the same logic, the EP 2030 fosters the integration between the historic spa town and its natural surroundings. The plan strengthened the strategic objectives for the rural areas, considered essential resources to develop a diversified territory characterised by a high quality of life.

4.2.3. Vichy

During the last twenty years, Vichy has diversified its activities with the goal of enhancing its architectural landscape and environmental heritage. The first urban interventions took place in the 1960s, when, to counteract the first major crisis of thermal tourism, the city promoted the construction of a series of major sport structures [

24,

76]. Beginning in 1987, the cooperation between the state, the Department of Allier, the Compagnie de Vichy—a private operator—and the municipality promoted a city-wide regeneration program: a plan for the refurbishment of the thermal architectural heritage and a plan to enhance the architectural quality of the city centre, including several hotels and its public spaces [

24,

76]. From this moment, Vichy also started to integrate its touristic offer with numerous projects, to strengthen its economic diversification and to increase the liveability for its residents. These objectives have been pursued also through the adaptive reuse of two of the city’s most symbolic spa sites: at the turn of the 2000s the bottling plant was reconverted into a regional hub dedicated to the development of young businesses and startups, while the former

Bains Lardy—the thermal baths, closed from 1967—reopened to the city as a University centre, whose regional relevance continues to grow. In the same period, the reform of the national urban planning law (LSRU 13 December 2000) defines new tools of territorial governance, integrating land use regulations with territory-wide strategic prescriptions: the planning criteria on the municipal scale (PLU) must be defined accordingly to the inter-municipal strategic plan for the territory (SCoT) [

77].

In 2011, Vichy became part of an intermunicipal association, the Vichy Communauté [

78], which has been working to set the 2030 territorial objectives to tackle the depopulation trend that has characterised the area since the 1990s. Economic vitality, resident quality of life and sense of place represent the three essential levers to increase local attractiveness. The strategic objectives are illustrated in the

Project d’Agglomeration (PdA) [

79], and the intervention priorities are framed within an integrated urban development plan—

Project de Développement Urbain Intégré (PdUI) [

80], which ensures the technical and economic feasibility of the projects by framing them within Regional Operative Programming and Smart Specialisation Strategy priority axes and to their relative funds, considered as a fundamental financial lever for the implementation of the interventions.

Through these efforts, Vichy aims to distinguish itself as a centre of excellence and innovation. Specifically, Vichy contributes to the achievement of territorial objectives through the promotion of sustainable housing solutions, improvement of existing building stock, strengthening of higher education, collaboration between local companies and the spa-rehabilitation sector, enhancement of the environmental heritage, improvement of commuting nodes, creation of a diversified touristic offer and improvement of the city’s image through the last two major interventions in its built thermal heritage: the recovery of the Parc des Sources and the redevelopment of the sport infrastructures.

4.3. Variations and Patterns

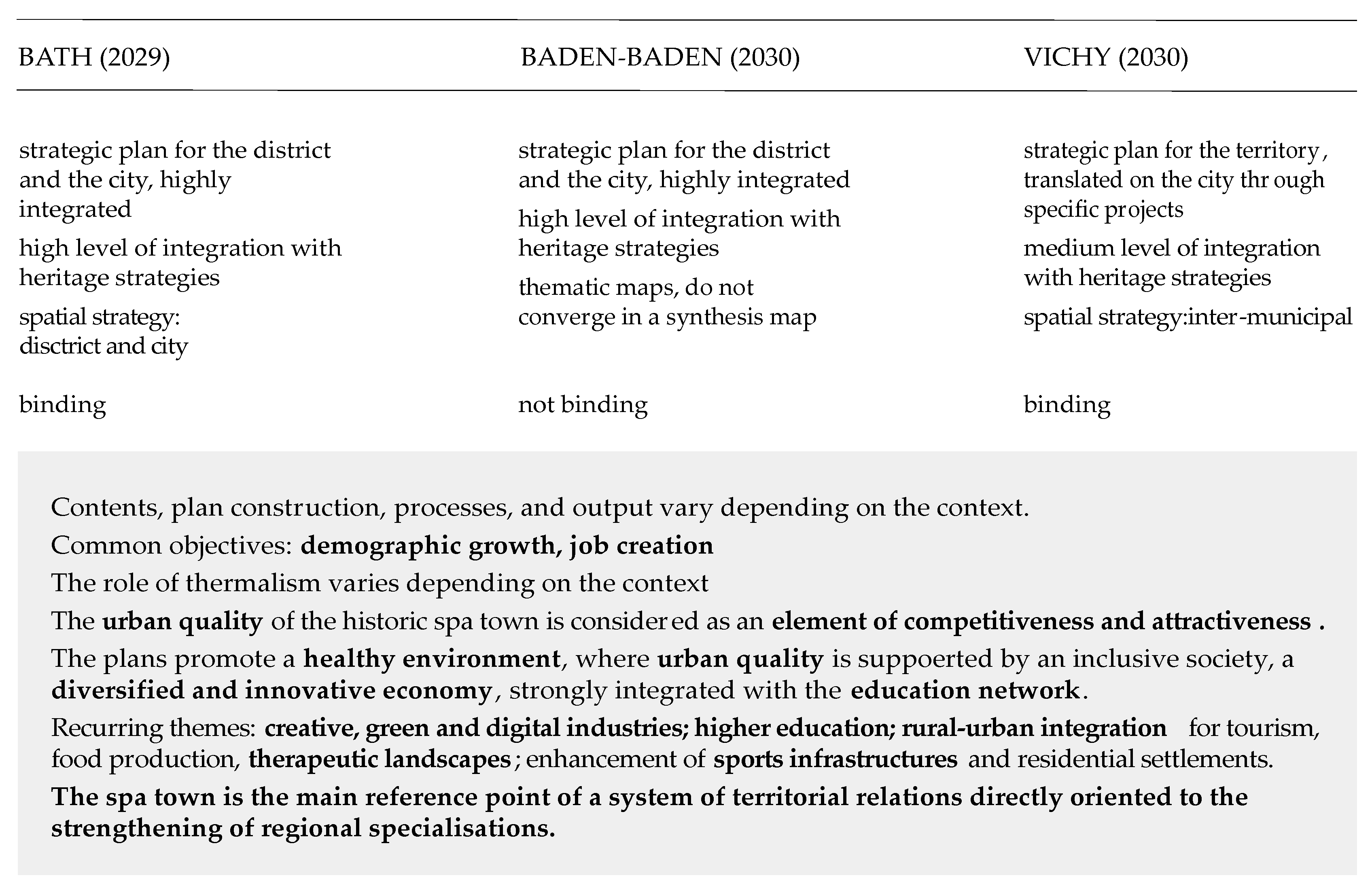

From the cross-reading of the three different contexts (see

Figure 1 and

Appendix A), it emerges that the nature and content of the plans, their level of integration with heritage policies and the level of public and private stakeholder engagement all varied. To some extent, the three contexts could be considered complementary, both in terms of processes and strategic priorities.

From a process point of view, the plans are characterised by the activation of governance networks composed of public, semi-public and private actors in different combinations. In the English case, strong cooperation with public and private trade associations and expert groups; in the German case, strong participation of public and private actors, citizenship, thematic experts and workshop facilitators; and in the French case, strong inter-municipal cooperation supported by technical experts.

The nature of the documents, being prescriptive and not binding, has been directly reflected in the strategy output, which assumes a more detailed spatial translation in the French and English cases (

Table A1). Nonetheless, the strategic nature of the plans has allowed for a comparison of the different administrative contexts, and some interesting considerations can be made about common thematic areas (

Table A2 and

Table A3).

Above all, it emerges how urban quality, even more than the crisis of thermalism, has represented the most critical factor for the decline of the tourist destination and for harming the sense of place for both tourists and citizens. This is a factor that has been considered with great awareness in all three contexts and, consequently, the requalification of the built cultural heritage represents one of the main drivers of local development and revitalisation policies. In all cases (the redevelopment of the image of the city of Bath, the protection of the historic landscape of Baden-Baden and the numerous interventions of urban regeneration and reuse of the built cultural heritage of Vichy) landscape, urban and architectural quality represent the main elements of local attractiveness. In particular, quality is proposed as a competitive advantage able to promote a healthy lifestyle in a socially and economically inclusive environment, embedded in a network of infrastructures dedicated to sport, education and culture, and capable of contributing to cultural production by attracting new investment and enterprises, such as digital and cultural industries, and by promoting a prolific environment for universities and research centres.

Within the territorial context, spa towns are identified as the main node of an integrated and balanced territorial system of proximity relations between towns and rural territories, a relationship of mutual exchange of services, products and living environments. Here, the adaptive reuse of built cultural heritage and the regeneration of the urban landscape play the role of opportunity spaces to attract activities beneficial for the whole region. The policy conducted by the city of Vichy at the turn of the 2000s has been exemplary: the abandoned thermal heritage was reused to strengthen regional business activities and educational offers. Today, such approach has been fully integrated within the inter-municipal planning, and strengthened by linking the priority urban transformation projects to the objectives of the regional Smart Specialisation Strategy and of the Regional Operative Programmes. Here, European Structural funds represent a fundamental financial lever for projects’ implementation.

5. Insights into the Italian Context

In Italy, the architectural heritage related to historic spa towns and, in general, thermal activities, represents a widespread territorial asset, in number and territorial distribution [

19,

21]. Spa towns are considered mature touristic destinations, whose relevance in terms of touristic potential and architectural quality has been highlighted by the Strategic Tourism Development Plan—STP 2017–2022 [

81]. At the same time, many spa towns are still dealing with the consequences of the crisis that hit the thermal sector at the beginning of the 1990s. The degradation of thermal heritage has become an urgent issue as it affects numerous buildings of considerable historic and architectural value throughout the national territory [

81]. While, at the turn of the 2000s, many small- and medium-sized spa companies succeeded in adapting their offer and meeting the changes of the rapidly evolving international tourism market, major public thermal baths did not manage to innovate services [

21,

82]. They entered a period of immobilism and inertia that contributed to their loss of attractiveness, underutilisation and abandonment after the public health service revoked its financial support [

82]. Currently, a considerable number of these buildings are still public property, mainly managed through public partnerships between municipalities and regions.

Since the 2000s, regions have been encouraged to define tools for the valorisation of the natural, historic and artistic resources of spa territories (L. 323/2000) [

83]. Although there has been input regarding the development of an integrated touristic offer [

2,

19,

21], an overall strategy for the recovery of this heritage still seems to be missing. The privatisation of the properties and of the management of these structures is proposed as ‘the way to go’ [

84] although these processes, except for a few virtuous cases [

85], have encountered numerous episodes of desert tenders, insolvencies in the management of the structures and have become an additional cost rather than a solution.

Due to the underuse, degradation and abandonment of such heritage, spa towns find themselves ‘not to have’ a public heritage of considerable impact on the urban fabric at all levels: land-use, economy, image and identity. The management of public spas and their integration within a wider vision for the city hence represent a fundamental point in the contemporary debate on the economic, environmental and cultural sustainability of spa towns’ local systems. Currently, the challenge is to reactivate these territories and their built heritage while considering alternative development models, including new ways of cooperation between public and private entities both in terms of property management and territorial planning.

5.1. Place-Based Research

A series of recent research projects (RP) led by Politecnico di Milano adds an interesting contribution to the debate. Through different research subjects, scale and interlocutors, these projects provide a global understanding of the evolution of the topical issues within the Italian context (

Figure 2).

Of particular interest for the current debate are the studies developed between 2016 and 2018. Moving from the concept of a ‘thermal cultural district’ (RP I and II) that identifies thermalism as the main driver for local development [

21,

86], the focus is gradually shifted from the economic sector of reference (thermalism) to the city and its territory.

RP III, carried out on behalf of the

Fondazione per la Ricerca Scientifica Termale—FoRST, investigated tools and strategies to promote the knowledge, management and enhancement of the Italian built heritage connected to thermalism through multi-criteria decision making methodologies [

87], to investigate its potential integration with touristic or service-related territorial networks and, in particular, with the one of the National Healthcare System [

88]. Through a series of case studies, the research highlighted a wide margin of an overlapping and a possible integration in terms of mission, architectural features and territorial distribution between thermal baths and Health Centres: multipurpose health facilities able to provide basic social and health services, such as prevention and rehabilitation, health education and social services, to all citizens, integrating, as territorial infrastructure, the primary hospital network [

89].

RPs IV, V and VI focus on the reality of Salsomaggiore Terme and on the enhancement of its built environment and its socio-cultural context. The three interventions, based on different scales and research moments, are part of the same global vision for the city. RPs IV and V represent two different phases of an integrated project concerning the reactivation of the abandoned thermal hotel ‘Tommasini’ [

90]: a listed public abandoned building located in the hearth of the Salsomaggiore Terme, within an area that has been identified as ‘a degraded urban area’ according to national indexes on social and urban decay [

91,

92] (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

RP VI represents a further step of the process, focusing on the overall urban regeneration of the same degraded area. Moving from three strategic development axes (tourism, education and health promotion) the project sets the 2019–2023 Agenda for the city. In doing so, it includes a series of programmatic actions and physical interventions that represent the starting point for the wider Urban Regeneration Strategy.

The three research projects have been developed to support the Municipality of Salsomaggiore Terme in the definition of the urban intervention strategies and the reuse programme of the building Tommasini, and in the application for national, regional and European funding for the implementation of the projects. Specifically:

D.P.C.M. 25 October 2015, Call for interventions for the social and cultural regeneration of degraded urban areas [

91]. Defined within the National Plan for the social and cultural redevelopment of degraded urban areas, the call allocates national funding for the implementation of urban regeneration projects based on the reactivation of public built cultural heritage for public purposes (RP IV);

ERDF-ROP Emilia-Romagna 2014–2020, axis 5, OT6 (valorisation of environmental and cultural resources) objective 1: interventions for the protection, valorisation and networking of cultural heritage, material and immaterial, to promote local attractiveness and the strengthening of the local systems (V);

Call for Urban Regeneration, an initiative promoted within the framework of the new regional planning law of Emilia-Romagna Region (LR 24/2017), born to support urban regeneration strategies through public funding for territorial cohesion allocated by the Region (RP VI).

Currently, parts of the ‘new’ Tommasini (

Figure 5)—a civic hub for tourism, education and health promotion (RP IV, V)—have been inaugurated and are fully functional while, in some sections of the building, the works are still ongoing [

90]. Meanwhile, the Urban Regeneration Agenda (RP VI) received full funding from the Emilia-Romagna Region for its implementation. The overall interventions of RP IV, V and VI represent an important example—if not the only one of considerable dimensions within a spa town in Italy—of an integrated approach to urban regeneration and reuse of the abandoned public built cultural heritage related to thermalism, an adaptive reuse process on various scales, which expands the concept of ‘thermal cultural district’ to wider cultural and non-cultural logics.

Fostered by new local relationships and stakeholder cooperation, the processes have functioned as a coordinated set of interventions. They envisaged a continuous interaction between public and private actors and promoted the integration between the punctual transformations of the reuse project and the broader urban regeneration agenda. Through a demand-driven programme, the former thermal hotel has been reintroduced into civic life and its functional program has been integrated with the regional strategic development axis, meeting some of the priorities of the Smart Specialisation Strategy of Emilia-Romagna (agri-food system, health promotion, cultural and educational industries) [

93].

Finally, the synthesis and coordination of the different objectives and actors also enhanced the technical and financial feasibility of the project (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). By breaking down the overall project into simple elements linked to specific themes, interests and capitals, the reuse project and the urban regeneration strategy have collected a series of parallel public and private funding activated in different time phases. This integrated set of interventions has allowed for the implementation of the various parts of the projects, avoiding that possible slowdown on one or more axes of financing would block the general outcome, while proposing a management and funding model that could represent an interesting alternative to privatisation processes [

94].

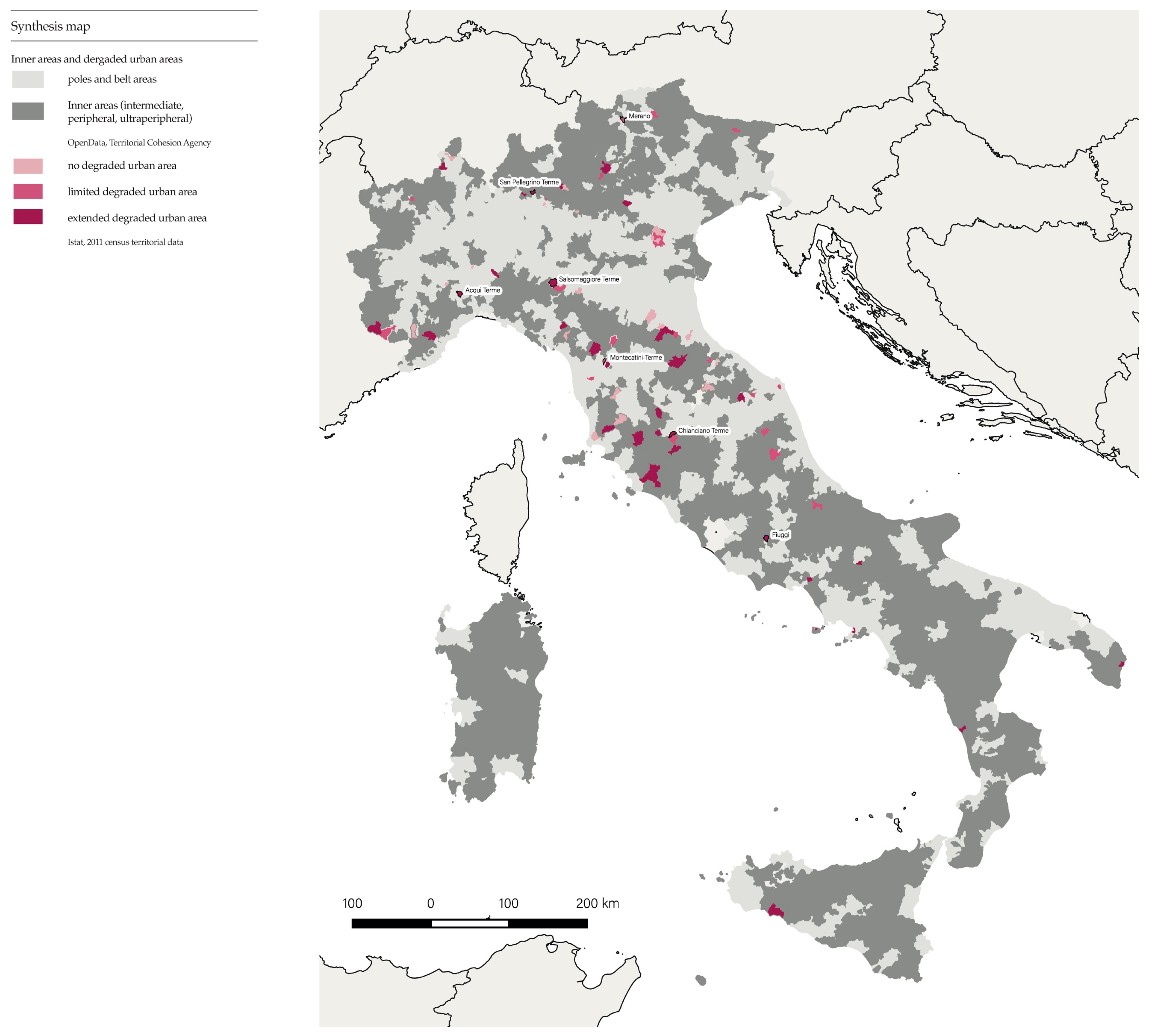

5.2. Italian Spa Towns and Fragile Territories: Which Relations, Which Integration?

The relevant scale of the degraded urban area identified within the historic centre of Salsomaggiore Terme has led to questioning to what extent the same conditions might be found in other spa towns nationwide. A GIS-based survey was carried out on a sample of thermal tourism municipalities classified by Istat in 2015. The urban decay index has been defined according to the definition given by the D.P.C.M. 25 October 2015 [

91] based on a set of indicators calculated from the spatial data of census sections [

92]:

and

where IDS indicates the ratio of unemployed, non-educated citizens and concentration of youngsters, and IDE indicates the ratio of residential buildings in a poor state of conservation [

92].

This analysis showed that around 70% of the thermal tourism municipalities include areas that fall within the classification of degraded areas; 40% of these situations include degraded urban areas of considerable extension (more than one census section), and in 96% of cases, a significant degraded area is present in neighbouring municipalities (

Figure 7). While acknowledging the limits derived from this definition of ‘urban decay’, which, in fact, includes limited factors in terms of social dynamics and environmental quality, the analysis has provided interesting insight into a widespread condition of environmental and social fragility. The investigation ‘captured’ the paradoxical condition of decay of cities that, historically, made of health and quality the generative cultural factors of their urban structures [

11].

The coexistence between these conditions of fragility and the complex value of spa towns as cultural landscapes has led to questioning the relationship between spa towns and another fragile territorial context: that of the Inner Areas, which are peripheral areas of the Italian territory that currently, after years of strategic disinvestment [

33,

34], are the target of a national strategy aimed at territorial cohesion and urban-rural rebalancing [

95,

96,

97]. An initial survey on the degree of interaction between these two contexts was carried out superimposing territorial datasets. From this overlapping emerges a particularly interesting picture, which shows how spa towns are distributed in a barycentric position between Inner Areas and the main urban centres (

Figure 7).

The question of the possible integration between these two territorial contexts becomes particularly significant when considering their common traits. On one hand, the critical elements such as an underused territorial capital, high social costs generated by production and consumption processes and, especially for the Inner Areas, social discomfort linked to the lack of accessibility to essential services, such as work, instruction, health and digital services [

33,

34,

95,

96,

98,

99]. On the other hand, the strategic objectives such as quality of life, social inclusion and job creation, aimed to reignite local development mechanisms and to rebalance demographic trends [

33,

34,

95,

96,

98]. All these are aspects that become particularly meaningful when considering the intrinsic qualities of the urban structure of the spa towns: accessibility, location and an urban environment particularly rich of public and private abandoned buildings of high architectural quality [

2,

6,

7,

11]. The high availability of the underused and abandoned built cultural heritage can certainly be understood as an opportunity for innovation: punctual if we consider the buildings as opportunity spaces; local when considering the synergies activated by the urban regeneration and adaptive reuse processes; and territorial when these processes are integrated in a wider vision for the region. From this perspective, the project of the territory represents an element that is as relevant as the heritage itself, potentially able to generate a network of new cultural, societal, political and productive centralities [

37].

6. Discussion

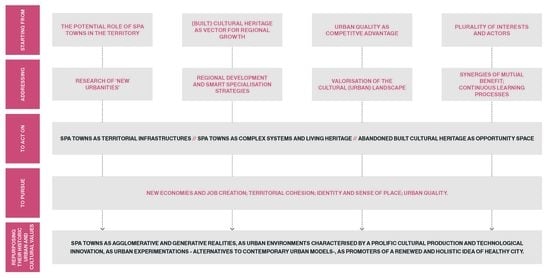

Within the hypothesis that in a renewed approach to the city and the territory, in search of new urbanities, spa towns can represent a privileged environment with high potential for innovation, this paper illustrated how integrated adaptive reuse and urban transformation practices can foster the implementation of urban transformation processes towards a sustainability transition. Circularisation logics have been broadened to the city as complex system, as cultural landscape, pursuing full interdependence between environmental, social, cultural and economic instances.

The discourse arises from the main challenges that European spa towns have faced over the last few decades: demographic and occupational decline and degradation of the built environment have been individuated as the main critical factors. Nonetheless, it is from the very moment of crisis that innovation can take place.

From the explorative analysis of the European scenario, it emerges that the transformative processes present similar dynamics, despite their structural differences related to the administrative and regulatory framework. Within a strategic vision for the city and the territory, spa towns are understood as a physical and cultural infrastructure able to contribute to territorial growth and cohesion, on the one hand by intercepting strategic regional development priorities, and on the other hand by pursuing an urban–rural rebalancing of the territories. The integration of local projects within Regional Operative Programmes and Smart Specialisation Strategies, in particular, allows for the pursuit of Sustainable Development Goals while unlocking potential funding to support public administrations in the valorisation of the built cultural heritage.

In a logic of greater economic resilience, the thermal tourism sector has been flanked by strategic development areas such as the higher education offer, the specialisation of services related to sport and wellness, the support of technological innovation linked to digital industries, and their interaction with other local specialisation fields. This is particularly meaningful for the Italian context, where the geographical distribution of the built heritage related to thermalism and its spatial relationship with the Inner Areas represent great potential in terms of territorial cohesion projects addressing the strengthening of mobility networks and the accessibility to healthcare and educational services.

Within this reference framework, which elects urban quality as a territorial resource and competitive advantage and a lever for attracting resources and talent, the adaptive reuse of the built heritage plays a key role as a catalyst for innovative synergies, combining, within its functional program and the processes for its implementation, cultural production with the production of economic and social values. Built heritage valorisation strategies overcome the ‘traditional’ dimension of conservation, embracing cultural and extra-cultural interests in a demand-driven logic, where heritage conservation, valorisation and urban development processes are integrated in one global vision.

Here, the strategic dimension of the urban project has been identified as an instrument and a process capable of supporting traditional planning tools in dealing with the uncertainty that architectural, urban and territorial transformations bring along, and with tackling different scales, times and transformation scenarios. Considering the city and its abandoned heritage as the physical infrastructure on which to act, the strategic plan is configured as a platform for connecting global and regional territorial energies on the local dimension: a platform for dialogue between the interests and demands of the different actors involved and the different times and places of transformation.

At the same time, change is enabled by cultural conditions and process characteristics, by a receptive context for change that can be associated with the transformative capacity of a place. These conditions refer to issues related to policy coherence, priority of actions, cross-sectoral cooperation and stakeholder involvement. In order to highlight which of these conditions emerged as potentially enabling factors for producing positive externalities within long-term Sustainable Development logics, they have been translated into a set of recommendations that focus on both thematic considerations and process characterisation. On a thematic level (1–5), these recommendations are built from the topical issues emerging from the various case studies. On a methodological/procedural level (6–10), what emerged from the international context have been integrated with the recent European Commission guidelines for Sustainable Urban Development [

59]. These are as follows:

Consider the spa town as a system-wide cultural district, where the valorisation of cultural heritage should not be translated into a nostalgic past, but rather unfold the economic and spatial potential of the places. Diversification and innovation underpin the resilience of local economic systems; therefore, the valorisation of existing networks or the creation of new synergies by combining thermalism and tourism with new or renewed cultural and extra-cultural industries is fundamental.

Consider urban quality as a competitive asset, a lever to attract resources and talents, able to contribute to local growth. Understood in its broadest sense, quality promotes a healthy and inclusive living environment, represents an element of attractiveness for working environments, and is reflected in the promotion of a cohesive social structure.

Consider spa towns as infrastructure for territorial cohesion and regional growth. Spa towns can represent a strategic asset in a network of proximity relations, a point of reference for work, culture and education, the main node of an integrated and balanced territorial system between urban and rural areas.

Envision abandoned built cultural heritage as a catalyst for change, in a demand-driven logic. Change is an integral part of heritage’s evolution and is understood not as critical aspect but as a resource to combine local identity with innovation and value-creation processes.

Recover the culture of the city. Consistent with the concept of living heritage, spa towns can ‘update’ their meaning by reinterpreting those elements that affirmed their historic identity as a healthy city: sustainable living environments, alternative to the consolidated urban models based on environmental and urban quality, slow rhythms and the strengthening of social relationships; a ‘healthy economy’ rooted in both the territory and international competitiveness; a context based on urban and architectural experimentations; and an agglomerative and generative reality where renovated or unprecedented synergies produce cultural and technological innovation.

Recognise strategic planning as a process capable of synthesising heritage and non-heritage interest on the infrastructure of the city. In order to produce positive externalities, the construction process of the plan will have to be characterised by specific elements in terms of governance, multi-sectoral and integrated approach, management and optimisation of resources, flexibility and the possibility of continuous revision and adaptation.

Support a multi-level, multi-stakeholder and participatory approach at all stages of process definition and implementation. Active networks—at national and international level—are to be intended as platforms for dialogue and for sharing good practices, as well as transversal or complementary expertise.

Embrace an interdisciplinary and interdepartmental approach to ensure the coordination of territorial resources and promote integration between built cultural heritage valorisation policies and regional strategic development axis.

Stimulate the activation of integrated intervention and funding opportunities promoted by the EU by establishing strategic funding units. Organise the projects on simple independent elements and activate public–private financing models. Promote investment on abandoned public built cultural heritage through 4Ps logics and through the definition of the relationship between adaptive reuse projects and regional development priorities.

Promote evidence-based decision making. The availability of qualified data is essential for the monitoring of projects and interventions, as well as to investigate the territorial contexts on a spatial base. Nation-wide research programmes oriented towards systemic knowledge and mapping of the architectural heritage related to thermalism are to be encouraged and supported.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposed a systemic and multidisciplinary reading of the themes and the factors that, within the context of historic European spa towns, are enabling a profound integration between the adaptive reuse of built cultural heritage, urban transformation practices and territorial development processes.

In presenting this investigation, the paper has addressed a variety of contexts and themes that, due to their complexity, would have required an in-depth analysis and dedicated dissemination. Nonetheless, this systemic approach is also the added value of the paper, as its aim is to recentre the debate on the urban dimension of spa towns, re-establishing a focus on their complexity as cultural landscapes and on the opportunities associated with their abandoned built cultural heritage. The paper identifies in the awareness of the transformation potential of these places the first and fundamental condition for innovation. Therefore, it addresses public practitioners and policymakers, as well as the main cultural institutions operating in the field, in order to foster an international discourse about the future—rather than the past—of these places, to go beyond tourist mechanisms and to promote proactive practices of value creation.

The matters presented in this paper have a particular relevance to the Italian context, where place-based research experiences have highlighted specific territorial conditions. However, the same logic can also be applied in other European contexts, which present similar territorial conditions, or different logics (in terms of territorial priorities) could be applied in different territorial contexts, yet adopting the same cultural framework. In this sense, it would be of great use to collect place-based experiences of adaptive reuse and urban regeneration practices from spa towns in various European regions.

The approach proposed in this study also reflects the contemporary European culture of human-centred living spaces, the ‘research of new urbanities’, where cities and regions can represent laboratories for interdisciplinary cooperation and innovation [

31,

33,

100]. Here, the valorisation of cultural (urban) landscapes and, therefore, of historic European spa towns, could represent a valuable contribution to the forthcoming debate and could contribute to a renewed rural–urban dialogue.

Further developments have also been suggested by contemporary conditions. First, the COVID-19 pandemic has sharpened spa towns’ difficulties related to tourist activities. In addition, the considerations made in the Italian context about the possible integration between the territorial networks of healthcare services and the built heritage of spa towns assumes today a particular relevance. With regard to post-traumatic rehabilitation paths, spa towns and their active and abandoned buildings could represent a valuable resource and, perhaps, even lead to reconsider of the role of thermalism itself. Finally, the pandemic has prompted us to reconsider, also thanks to the possibilities offered by technological innovations and remote working, the geographies of value production, the quality of the spaces in which we live and work and their impact on our psycho-physical wellbeing, confirming the value of places characterised by landscape and environmental quality, proximity relations and social inclusion, and further strengthening the idea that spa towns could contribute, in many European contexts, to the development of new territorial relations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, V.F.; methodology, V.F. and M.P.V.; validation, V.F., M.P.V. and E.F.; formal analysis, V.F.; investigation, V.F.; resources, V.F., M.P.V. and E.F.; data curation, V.F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.F.; writing—review and editing, V.F. and M.P.V.; visualisation, V.F.; supervision, M.P.V. and E.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The paper is based on the PhD thesis ‘Co-evolving Significance. Processes and outlines for the valorisation of spa towns’, authored by Viola Fabi, supervised by Emilio Faroldi and Maria Pilar Vettori, and tutored by Stefano Capolongo (Politecnico di Milano). Academic contributions to the research and discussion: Stefano Della Torre, Politecnico di Milano; Christer Gustafsson, Uppsala University; Patrizia Romei, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Contribution of public and private institutions: Municipality of Salsomaggiore Terme; Fondazione per la Ricerca Scientifica Termale; European Historic Thermal Towns Association. The interviewee: Tony Crouch—City of Bath, World Heritage Site Manager; Lisa Poetschki—Municipality of Baden-Baden, Head of World Heritage Nomination and Urban Design Department; Smriti Pant—Municipality of Baden-Baden, Research Associate of World Heritage Nomination and Urban Design Department; Anke Matthys—Municipality of Vichy, Deputy City Project Manager, Local Project Coordinator of UNESCO application Great Spas of Europe.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Comparative study. Nature and contents of the planning tools.

Table A1.

Comparative study. Nature and contents of the planning tools.

| | | Bath | Baden-Baden | Vichy |

| | Document | Local Development Framework | EP 2030 | Bebauungs-Plan | PdA | PDUI | SCoT | PLU |

| | subdocuments | Core Strategy | Placemaking P. | Suppl. doc. | - | - | | | PADD | RP | DOO | |

| | approved | 2104 | 2017 | - | 2018 | - | 2015 | | 2013 | | | - |

| | horizon | 2029 | 2029 | - | 2030 | - | 2025 | 2020 | 2030 | | | - |

spatial

dimension | regional | | | ● | | | | ● | | | | |

| inter-municipal | ● | ● | ● | ● | | | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| municipal/local | | ● | ● | | ● | | ● | | | ● | ● |

temporal

dimension | long term | ● | ● | ● | ● | | | | ● | | | |

| medium-term | ● | ● | ● | ● | | ● | | ● | ● | ● | |

| short term | | | ● | | | ● | ● | | | | |

| contents | diagnostics | ● | | | | | | | | ● | | |

| general principles | ● | | | ● | | ● | | ● | | | |

| strategic objectives | ● | | | ● | | | | ● | | | |

| specific objectives | | ● | | ● | | | ● | ● | | ● | ● |

| specific actions | | ● | | ● | | ● | ● | | | ● | |

| thematic documents | | | ● | | | | | | | | |

| indication of strategic areas of intervention | ● | ● | | ● | | ● | ● | | | ● | |

| coordination: priorities in projects and actions | | ● | | ● | | ● | ● | | | | |

| indication of protected areas and listed buildings | | ● | | | ● | | | | ● | | ● |

| binding regulations | | ● | | | ● | | | | | ● | ● |

economic

sustainability of the interventions | European Structural and Investment Funds | | | | | | | ● | | | | |

| other regional or local funds | | | ● | | | | ● | | | | |

| reference to public-private co-financing mechanisms | | | ● | | | | | | | | |

Table A2.

Comparative study. Recurring themes and objectives of the strategic plans of Bath, Baden-Baden, Vichy.

Table A2.

Comparative study. Recurring themes and objectives of the strategic plans of Bath, Baden-Baden, Vichy.

| Thematic Areas | General Objectives | Specific Objectives |

|---|

| infrastructure and mobility | exploit existing infrastructure | strengthen the residential settlements |

| encourage public transportation | favour soft mobility networks |

| natural resources andenvironmental quality | preserve the natural landscape | preserve the natural landscape from urbanisation |

| enhancement of natural resources | integrate thermal water management into development projects |

| enhance the natural and cultural landscape through sustainable development |

| foster a development of the territory that respects the environment | promote densification and zero soil consumption |

| historic urban landscapeand urban quality | preserve the historical landscape | ensure the protection of the open spaces of the consolidated city |

| strengthen quality, recognisability and urban identity | strengthen identity and development of smaller settlement areas |

| promote the urban environment as an added value in the perception of workplace quality |

| promote the usability of the historic city | ensure the presence of socialising spaces in residential areas |

| promote the usability of heritage through digital information systems |

| connect the public spaces of the city through green corridors |

| tourism | strengthen the thermal tourism specialisation | increase international tourist attraction |

| enhance territorial touristic attractiveness | increase the attractiveness of rural tourism |

| increase the attractiveness of cultural tourism through the programming of cultural events |

| invest in the quality of accommodation |

| integrate and connect existing touristic facilities |

| economy and job creation | affirm the economic vocation of the territory | support commercial attractiveness through the location of agglomeration areas |

| support and promote neighbourhood exercises |

| identify new complementary development axes | promote the development of new entrepreneurship |

| foster the development of future-oriented societies and industries |

| research and education | consider the educational offer as a factor of competitiveness | invest in university education |

| social inclusion and cohesion | integration and participation | increase the share of housing that could be of interest to young families, elderly and young people (in particular students) |

| cultural diversity | strengthen the cultural involvement of private cultural and professional associations |

Table A3.

Comparative study. Interpretative matrix.

Table A3.

Comparative study. Interpretative matrix.

| | | Bath | Baden-Baden | Vichy |

|---|

| the spa town in the construction of the territory | What is the degree of integration between urban and territorial strategic priorities? | High. The spatial strategy for the city of Bath represents the local scale declination of regional development objectives. | Medium. The strategic plan takes up the regional principles in terms of mobility and environmental quality and is a guidance document for the local scale. | High. The territorial plan (SCoT) has a high level of integration with metropolitan and regional planning and is prescriptive towards the local plan (PLU). |

| Does the spa town have a relevant role in the territorial strategy? | Yes. The spa town is the main urban centre of the district. | Yes, although this is perhaps also a condition dictated by administrative characterisation (kreisfrei Stadt). | Yes. Vichy represents one of the main urban nodes and intercepts many of the priority projects of the inter-municipal agglomeration. |

| Are there recurring themes, common to the three strategies? | Apart from specific local objectives, it is possible to identify some recurring themes common to development strategies. These can be identified in: Strengthening of the territorial network of reference, creation of proximity networks; Strengthening of the educational offer, with particular attention to higher education; Enhancement of sports infrastructures; Promotion of urban quality.

These elements contribute to the qualification of spa towns as ideal places for education and cultural production, for attracting technological or digital creative industries that, needing limited space for business development, are increasingly looking for places characterised by high environmental quality of the workplace and of the surrounding areas. |

| enhancement of the thermal heritage | Is the thermal tourism one of the main strategic lines? | No, but cultural and rural tourism are. The spa activity is now more related to a daily dimension. | Yes, integrated with conference, cultural and rural tourism. | Yes, integrated with cultural and rural tourism. |

| Is the adaptive reuse of abandoned historic building included in the strategy? If so, are they related to thermalism? | Yes. Not related to thermalism but related to the offices of the Ministry of Defence, situated in the city centre and abandoned since 2011. | Yes. Not related to thermalism but related to the old military area (Cité). | Yes, such as the redevelopment of the Parc des Sources and the reactivation of disused industrial buildings linked to the old bottling plant. |

| Has the city promoted projects dedicated to the valorisation of the built thermal heritage? | Yes. The reactivation and redevelopment of the Georgian Baths. | Yes. After the ‘demolishing philosophy of the Sixties’ the approach shifted strongly on conservation of the buildings and the urban fabric. | Yes. Several episodes of refurbishment and reuse of the thermal heritage (congress centre, university centre, tertiary hub). |

| coordination of funding and actors | Does the strategy make explicit reference to European programmes and funds? | (not applicable) | No. | Yes. The strategic priorities are openly related to regional development programs and European funding mechanisms. |

| Did the strategy imply a consultation with the local private actors? | Yes, especially in the development of the Enterprise Area Masterplan. | Yes. The plan has been co-produced involving also private actors in a series of thematic workshops. | No. |

| Does the strategy refer to active participation tools? | No. The studies and the documents ‘before’ the strategy do. | Yes, the strategic plan is highly participated, citizens took part to the thematic workshops. Additionally, the UNESCO application was borne from a participated initiative. | Not directly with the citizens. Active cooperation has been fostered on an inter-municipal level. |

References

- Butler, R. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. Le Géographe Can. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romei, P. Territorio e Turismo: Un Lungo Dialogo. Il Modello di Specializzazione Turistica di Montecatini Terme; Firenze University Press: Florence, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bossaglia, R. Stile e Struttura Delle Città Termali; Nuovo Istituto d’Arti Grafiche: Bergamo, Italy, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, L. Villes d’eaux en France; Fernand Hazan: Paris, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrassé, D. (Ed.) 2000 Ans de Thermalisme: Économie, Patrimoine, Rites et Pratiques. In Proceedings of Royat Conference; March 1994; Institut d’Études sur le massif Central: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Faroldi, E. Città, Architettura, Tecnologia: Il Progetto e la Costruzione Della Città Sana; Unicopli: Florence, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gillette, L. Thermae Europae. Discovering Art, Architecture and Heritage in Europe’s Spa Towns; Culture Lab Editions: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Farré, M.B. Estaciones termales europees: Entre la ciudad y el territorio. QRU: Quad. de Recer. en Urban. 2015, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, G. Progettare la città per le vacanze in Italia tra 1900 e 1950. In Architettura e Paesaggi di Villeggiatura in Italia tra Otto e Novecento; Mangone, F., Belli, G., Tampieri, M.G., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2015; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zucconi, G. Ferrovia e ville d’eaux: Tre casi studio. In Architettura e Paesaggi di Villeggiatura in Italia tra Otto e Novecento; Mangone, F., Belli, G., Tampieri, M.G., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2015; pp. 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, B. Aspetti del progetto urbano nelle città termali. In L’urbanistica delle Città Termali: Analisi e Prospettive. Proceeding of the National Conference in Abano Terme, 26–27 March 1993; Dinale, F., Ed.; Francisci Editori: Padua, Italy, 1993; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zanni, N. L’immagine della città termale. In Da Bath a Salsomaggiore; Guerini e Associati: Milan, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrassé, D. Los salones de Europa. Balnearios y literatura. In Ciudades Termales en Europa; Moldoveanu, M., Ed.; Lunwerg: Barcelona, Spain, 1999; pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Carribon, C. Villes d’eaux, villes de loisirs. Hist. Urbaine 2014, 41, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Venuti, G. Urbanistica e termalismo in Terme e territorio. In Proceedings of the Comitato di coordinamento per le attività promozionali delle città termali dell’Emilia-Romagna, Salsomaggiore Terme, Italy, 19–20 November 1976; pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Toulier, B. Architecture des villes d’eaux: Stations thermales et stations balnèaires. In Villes d’eaux des Pyrénées Occidentales: Patrimoine et Devenir; Jarrassé, D., Ed.; Faculté des lettres et sciences humaines de l’Université Blaise-Pascal—Collection thermalisme et civilisation: Clermont-Ferrand, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Route of Historic Thermal Towns. Cultural Route of the Council of Europe. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes/european-route-of-historic-thermal-towns (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- UNESCO. Great Spas of Europe. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5928/ (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Rocca, G. (Ed.) Dal turismo termale al turismo della salute: I poli e i sistemi locali di qualità. Geotema 2009, 39, 1126–7798. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine, L.; Schneider-Mauch, E. Inventaire du patrimoine thermal—Dossier collectif; Route des Villes d’Eaux du Massif Central: Royat, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Faroldi, E.; Cipullo, F.; Vettori, M.P. Terme e Architettura: Progetti, Tecnologie, Strategie per una Moderna Cultura Termale; Maggioli: Santarcangelo di Romagna, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vettori, M.P. Il comparto termale tra strategie aziendali e valori culturali. In Teoria e Progetto. Declinazioni e Confronti Tecnologici; Faroldi, E., Ed.; Allemandi: Turin, Italy, 2009; pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cour de Comptes. Thermalisme et Collectivités Territoriales, un Système Fragile: Le cas Occitan. 2019. Available online: https://www.ccomptes.fr/system/files/2019-02/11-thermalisme-collectivites-territoriales-systeme-fragile-Tome-1.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Béraud, J.F. (Ed.) Premières Rencontres Nationales sur l’Architecture et le Patrimoine Thermal des Villes d’Eaux. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Association Nationale des Maires des Communes Thermales, Vichy, France, 22 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Crecente, M. Presentation at the General Assembly of EHTTA; European Historic Thermal Towns Association: Galaalti, Azerbaigian, 30 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gillette, L. Thermae Europae. In Safeguarding Europe’s Spa Heritage; A critical apparisal; Culture Lab Editions: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. La production de l’espace. L’Homme & la Société 1974, 31, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffestin, C. Nature et culture du lieu touristique. Méditerranée 1986, 58, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J.W. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram, M.; Borgström, S.; Farrelly, M. Urban transformative capacity: From concept to practice. Ambio 2019, 48, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, L.F. The City and the Territory System: Towards the “New Humanism” Paradigm. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sacco, P.L. Medium-small sized art-cities and culture-led development: Can we look ahead and not behind? Techne 2017, 14, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, A. (Ed.) Riabitare l’Italia. Le aree Interne tra Abbandoni e Riconquiste; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carrosio, G. I margini al Centro. L’Italia Delle Aree Interne tra Fragilità e Innovazione; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a reformed Cohesion Policy. In a Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations; Indipendent Report to the European Commission; Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. A Territorial Approach to the Sustainable Development Goals: Synthesis Report; OECD Urban Policy Reviews; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, A. Il progetto Locale: Verso la Coscienza di Luogo; Bollati Boringhieri: Turin, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Conclusions on Cultural Heritage as a Strategic Resource for a Sustainable Europe; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, C. Conservation 3.0—Cultural Heritage as a driver for regional growth. SciResIT 2019, 9, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Luiten, E.; Renes, H.; Stegmeijer, E. Heritage as sector, factor and vector: Conceptualizing the shifting relationship between heritage management and spatial planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1654–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHCfE Consortium. International Cultural Centre; Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe: Krakow, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.L. Cartaditalia; Special Issue EYCH; Istituto Italiano di Cultura: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt-Grau, A.; Busquin, P.; Clausse, G.; Gustafsson, C.; Kolar, J.; Smith, B.; Spek, T.; Thurley, S.; Tufano, F. Getting Cultural Heritage to Work for Europe—H2020 Expert Group in Cultural Heritage; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda. In Proceedings of the United Nations Habitat III, Quito, Ecuador, 17–20 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, C.; Rosvall, J. The Halland model and the Gothenburg model: A quest toward integrated sustainable conservation. City Time 2008, 4, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, G.L. The role of cultural urban landscape. Towards a new urban economics: New structural assets for increasing economic productivity through Hybrid processes. Hous. Policies Urban Econ. 2014, 1, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. A coevolutionary approach to the reuse of built cultural heritage. Il patrimonio culturale in mutamento. Le sfide dell’uso. In Proceedings of the Convegno Scienza e Beni culturali, Bressanone, Italy, 1–5 July 2019; pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/ (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape. In Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; Wiley-Blackwell: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.L.; Ferilli, G.; Blessi, G.T.; Nuccio, M. Culture as an Engine of Local Development Processes: System-Wide Cultural Districts I: Theory. Growth Chang. 2013, 44, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, S. Lezioni imparate sul campo dei distretti culturali. IL Cap. Cult. 2015, 3, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Stanojev, J.; Gustafsson, C. Smart Specialisation Strategies for Elevating Integration of Cultural Heritage into Circular Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Gravagnuolo, A. Circular economy and culturale heritage/landscape regeneration. Circular business, financing and governance models for a com-petitive Europe. BDC Circ. City Cult. Herit. Interplay 2017, 17, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, J.; Boelens, L.; Balducci, A.; Wilkinson, C.; Nyseth, T. Strategic Planning in Uncertainty: Theory and Exploratory Practice. Town Plan. Rev. 2011, 82, 481–501. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L.; Balducci, A.; Hillier, J. (Eds.) Situated Practices of Strategic Planning. An International Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]