Abstract

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) continues to receive greater attention in the current business world. Many studies on CSR focus on manufacturing or industrial companies by examining external CSR activities from external stakeholders’ perceptions. However, academic institutions such as higher education institutions (HEIs) remain highly unexplored in the context of internal corporate social responsibility (ICSR). Employees are the most valuable and vital assets for every business organization. Therefore, this study focuses on CSR’s internal dimensions to determine its impact on social performance in HEIs in Ghana. Recognizing the social exchange theory (SET), we specifically examined the effects of five internal CSR dimensions (i.e., health and safety, human rights, training and development, workplace diversity, and work-life balance) on social performance. We used a multi-case approach to assess internal CSR activities in private and public Ghanaian universities. We purposely selected three public universities and one private university because of their varying contexts and academic mandates. We used structured questionnaires to collect data from both teaching and non-teaching staff of the selected universities. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to assess the data. We found that health and safety, workplace diversity, and training and development positively and significantly impact social performance. At the same time, human rights and work-life balance have an insignificant effect on social performance. Thus, ICSR practices have a substantial influence on both employees’ and organization’s performance, and hence this study gives important implications for both researchers and practitioners

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is not a novel concept in management and business practices. The root of the CSR concept can be discovered in the 1950s. However, CSR’s intent became virtually universally endorsed in the late 1990s and promoted by all citizens in society, governmental and non-governmental agencies, corporations, and individuals. According to [1], CSR is “an open and transparent business practice based on ethical values and respect for employees, communities, and the environment, contributing to sustainable organizational success”. There are extensive studies on CSR which have already established a positive effect on business organizations. Past literature has revealed some significant benefits of CSR regarding an organization’s competitive advantage [2,3], company prestige [4], and increased financial performance [5,6,7].

CSR means business organizations’ actions to promote and protect some social welfare beyond the immediate interests of organizations and their shareholders as required by law [8]. Most scholars and researchers believe that CSR’s concept is multi-dimensional, which relates to several and diverse corporate stakeholders [9,10,11]. In Ghana, for instance, “CSR is related to capacity building for sustainable living. It has respect for cultural differences and discovers business opportunities in developing skills of employees, the community, and the government” [12]. Ref. [13] explained CSR initiatives in Ghana as organizations’ strategic decisions to voluntarily undertake the social responsibilities that hinder their corporate goals. CSR falls under non-governmental interferences to address some developmental difficulties encountered by the nation. Predominantly, CSR initiatives concerning social investments are carried out by large-scale manufacturing, banking sectors, telecommunication companies, and corporations in the oil and gas and mining industries. The majority of companies that are engaged in CSR activities in Ghana are owned by foreigners.

Managing CSR activities has been acknowledged as the most effective means for business organizations to develop a positive reputation and trademark, leading to sustainable competitive advantage [14]. Interestingly, CSR has been a gradually advancing area of focus in academia. Some HEIs perform CSR activities for the advantage of their staff or stakeholders, including lecturers, administrators, students, and the community. However, existing CSR research predominantly focused on the perspective of consumers. Little empirical research has examined internal CSR from the employee perspective, especially in the view of academic institutions. Even though earlier studies have investigated the influence of CSR on employees, they primarily focused on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and how the business organization’s external CSR activities affect all stakeholders. Contrarily, determining the impact of internal corporate social responsibility (ICSR) activities on academic institutions’ social performance has been generally overlooked.

Internal CSR activities relate directly to employees’ psychological and physical work environment [15]. ICSR has also been defined as “socially responsible behavior by a company towards its employees” [16]. This behavior is mainly articulated via employee-oriented CSR practices such as favorable working environment, work-life balance, fostering employment stability, skills development, empowerment, diversity, and substantial employee involvement. The current evolving issues on CSR initiatives focus on health, education, entrepreneurship, social, environmental, and sports development. Similarly, CSR activities in Ghana are mostly found in mining, education, sports, coastline, and oil and gas production services. Ref. [17] states that Ghana’s businesses focus on primary education, community safety, health care, environmental damage, and consumer protection. However, we observed that CSR in Ghana is commonly discussed in connection with business organizations, while only a few studies consider HEIs. Besides, more attention has been given to external CSR activities than internal CSR activities. Thus, a handful of empirical studies has focused on ICSR practices in HEIs. There has also not been an assessment of the relationship between ICSR practices and social performance in HEIs. This current study examines this relationship in the context of HEIs in Ghana.

Emphatically, employees’ ICSR activities are a critical aspect of an organization’s social responsibility. Indeed, employees are the greatest treasured asset in every organization. The organization’s success and failure ultimately depend on them. Therefore, their social needs and well-being must importantly be considered. Regardless of extensive research on CSR in various fields in Ghana, no studies had explored the relationship between ICSR activities and the possible effects on organizational outcomes. Moreover, the case of ICSR and social performance in HEIs is critical to be studied. Hence, this study aimed to bridge this research gap by investigating the impact of five essential dimensions of internal ICSR activities on social performance in HEIs.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Concept of CSR

CSR is all over business organizations, sectors, and industries in today’s world and has practically become global [18]. It does not only focus on the contributions of business organizations made to society but also covers an extensive scope of business ethics, corporate control, investment, and environmental sustainability to the broader community and academic institutions. That is to say, CSR activities and implementation are not only relevant for corporations and industries but are also becoming a concern for HEIs. Ref. [19] described CSR as any corporation that satisfies its stakeholders’ social needs at any time. These societal needs involve ethical, economic, legal, and philanthropist or discretionary expectations of the society. However, other researchers [20,21] opposed Carroll’s explanation and established that every organization, in one way or the other, has some additional responsibilities which go above the economic and legal matters in their operations or organizational culture.

CSR is categorized by internal and external factors [22]. External CSR is the social responsibility aimed at consumers, society, local communities, and the natural environment [11,23]. According to [9], CSR issues related to consumer care and commitment to customers, providing quality goods and services, and protecting their interests beyond law requirements. Among the CSR activities to the society include community development, generous donations, collaborations with non-governmental agencies, etc. [15,24]. The environmental issues concerning CSR activities include environmental protection initiatives, reducing pollution, and activities that focus on sustainability [9,15]. In contrast, ICSR includes those activities that business organizations perform to satisfy employees’ desires, such as providing quality employees’ health and safety, ensuring growth and development, and enhancing organizational fairness concerning employees [10,25]. Ref. [22] explained that ICSR also relates to human resources like training, development, and labor participation that affect employee wellbeing.

Ref. [15] combined four different groups of stakeholder frameworks to expand the CSR activities. They consist of CSR to the government, consumers, social and non-social stakeholders, and employees. However, with this enhancement of the stakeholder framework, this study focuses on only one dimension of this framework, which is CSR to employees. CSR for employees describes an organization’s actions concerning employees’ career opportunities, training, development, natural and conducive working environment, and friendly strategies and support [26]. Ref. [27] clarified that potential employees need favorable consideration from a good CSR.

Organizations are identified with a group of internal and external stakeholders. Some CSR activities of most firms are directed towards internal stakeholders. Employees are considered the most prominent among these stakeholder groups within every organization. From the perspective of the stakeholder theory, there is the need for organizations to extend their duties beyond their economic boundary and to consider the social good directed towards either internal or external social dimensions of the organization [28]. CSR initiatives are intended to satisfy stakeholders, particularly employees (prominent internal stakeholders) in the organization. However, both internal and external stakeholders vary in importance, size, activism, proximity, magnitude, and visibility [29].

As evidenced in the study by [29], CSR involves a wide range of activities and practices. The nature and type of the target audience determine the differences between these activities and practices. CSR initiatives are characterized by some antecedents and consequences. By this notion, most past studies primarily attempt to examine what CSR antecedents yield in terms of certain outcomes. Remarkably, these past studies treat CSR antecedents as an aggregate variable whether those activities relate to internal or external. Thus, analyzing CSR as an aggregate entity makes it difficult to identify those internal or external CSR activities that significantly demonstrate an organization’s profound engagement in CSR practices. This has resulted in increased awareness and interest among researchers and practitioners about the need to decompose the aggregation of CSR. Refs. [30,31] argued that an aggregate CSR score might be deceptive since it does not indicate the accuracy of an organization’s involvement in CSR practices. In a similar context, ref. [32] put forward that it is crucial to disaggregate social performance so that it becomes easy to identify the trade-offs within social performance and to determine resource allocation for such activities. Further, they explained that it is essential to disaggregate CSR dimensions from an aggregate score to specific dimensions. Thus, each of the social dimensions has well-defined characteristics and has to be thoroughly investigated. This explains why the new paradigm of CSR studies focuses on the specific attributes of CSR activities regarding internal versus external CSR practices.

As regards CSR on aggregate scoring, there have been usually inconsistent results on CSR antecedents and outcomes produced by many researchers in most past studies. Particularly, the results of studies that relate to both internal and external antecedents have been ambiguous in their understanding, interpretation, and practicality due to the use of CSR as an aggregate function. This suggests different effects and performance outcomes across different CSR antecedents. Contextually, the variability in outcomes may not be attributable to the CSR aggregate score but rather the allocation of resources to specific CSR dimensions producing better performance outcomes. Thus, we agree with [32] that it is very crucial to “unpack” CSR from aggregation to disaggregation (i.e., specific internal and external dimensions). Such CSR disaggregation from the perspective of stakeholders helps to determine the dynamics in terms of how the internal CSR activities relate to the external CSR activities or the relationships between the dimensions in either the internal or external independently. It is also vital to consider specific CSR determinants in the face of internal CSR versus external CSR.

It must be pointed out that internal CSR equally has an influence on some aspects of an organization’s choices in the context of resource allocation. Given the internal CSR activities and practices, it is the responsibility of firms to respond affirmatively to the concerns of employees. This study gives profound insights into five specific internal CSR dimensions that are worth examining in HEIs. They are health and safety, work-life balance, training and development, workplace diversity, and human rights. These specific dimensions have not been analyzed in the context of determining their effects on social performance in higher educational institutions. Hence, this current study investigates how these specific internal CSR activities impact social performance and the extent to which each affects social performance in HEIs. In this sense, there can be an appropriate commitment to the allocation of resources to those activities that matter most to yield positive performance outcomes.

2.2. Internal CSR (ICSR)

Ref. [33] explained in their work that ICSR is a stakeholder approach of providing or satisfying the stakeholders’ needs and interests that can be affected by the organization’s operational activities. It is an action done in the organization to improve employees’ career and personal life, influencing their performance and productivity and directly affecting their profitability. Internal CSR is CSR activities that concern the employees’ psychological and physical working environment [15]. It is related to employees’ wellbeing, such as their health and safety, training and development, equality of opportunities, involvement in the business organization, and work-family relationships [34]. Similarly, ICSR may also include a business organization charitably performing its responsibility towards its employees and being sensitive to provide their specific social needs and preferences. Moreover, ICSR focuses on the personal and career development of employees. This capacity development could be more than strategic workforce training that can build the organization’s human capital and offer employees volunteer opportunities to improve themselves.

Ref. [35] stated that an organization’s success emanates from skilled, motivated, and satisfied employees who can fulfill customer needs and differentiate from competitors. Many business organizations still challenge employee motivation and satisfaction. Likewise, some researchers identified that even though a good salary attracts employees, other factors also influence employees’ motivation and satisfaction. Providing the necessary social needs to employees could retain them in the long run and increase productivity.

Furthermore, ICSR initiatives that directly influence individual employees can contribute to positive employee behavior and attitudes. It can generally affect organizational effectiveness, resulting in a good performance [36]. Other empirical evidences also suggests that workplace wellbeing ensures employees’ productivity, which helps prevent or reduce absenteeism, labor turnover, and lackadaisical attitudes towards work performance. Ref. [37] suggested that organizations with effective socially responsible cultures can retain their workforce. Thus, ICSR practices’ dimensions create a motivational atmosphere in the organization, decrease the organization’s operation cost, and improve its productivity [38]. Most employees become motivated and satisfied due to ICSR practices in the organization, especially when they become aware of their necessary steps concerning their wellbeing and social needs.

Several studies have deepened the understanding of the antecedents and outcomes of an organization’s CSR [39]. However, some empirical evidences show that internal CSR is positively related to an organization’s reputation and performance (e.g., ref. [35,40]). This has resulted in the recognition of the CSR concept and its relevance to organizations and institutions. There is still much supportive empirical evidence in the extant literature that encourages a steady investigation and implementation of CSR activities in many organizations and institutions. Such an effort is a way to control employee turnover for achieving better and sustainable organizational growth and development. For instance, ref. [41] suggested that ICSR significantly impact employees behavior because it offers a sense of just and fairness to the procedures and process in the internal affairs of an organization. Their study revealed that ICSR implementation creates procedural justice in the organization, which influences organizational attractiveness resulting in lower turnover of employees. Ref. [16] revealed in their studies that ICSR is a relevant concept improving employees’ affective organizational commitment. Their findings concluded that ICSR is an essential issue and has to be addressed well by an organization so that the employees will work in the best interest of the organization.

In addition, ref. [42] assessed the effect of ICSR on employee engagement. Their study established that ICSR was significantly and positively correlated with employee engagement. They further explained that employees perceived ICSR in a positive sense in their engagement at the workplace. Therefore, ICSR is an essential factor to improve employee engagement at their workplace, which subsequently increases employees’ job output and hence increases organizational performance. The study of [43] on internal CSR and employee performance through commitment in the hospitality industry discovered that ICSR has a positive effect on organizational commitment leading to greater output of the organization. They indicated that most managers and executive bodies had given greater attention to the strategies and implementation of ICSR to increase organizational commitment, which impacted both employees and overall organizational performance.

Similarly, HEIs also recognized ICSR as an important social responsibility. These ICSR dimensions are specific and applicable in HEIs as studied in other manufacturing industries. However, the extent of recognition of ICSR practices varies among organizations, and this reflects how much emphasis or importance an organization attaches to specific ICSR activities. This means that organizations do not need to necessarily have equal emphasis between internal CSR and external CSR activities because other factors such as organizational capabilities and innovative strategies influence the dimensionality of corporate social responsibilities.

Interestingly, the awareness of internal CSR continues to increase among researchers and practitioners, especially about those specific internal CSR practices that impact stakeholders within an organization. A set of such specific ICSR activities that remain viable in the extant literature include health and safety, work-life balance, training and development, workplace diversity, and human rights. However, these specific dimensions have not been analyzed to ascertain their effects on social performance in higher educational institutions. Hence, this current study aimed at investigating how these specific internal CSR practices impact social performance and also assessing the effect of each of these on social performance in HEI.

2.2.1. Health and Safety

Health means freedom from emotional or physical illness, whereas safety refers to protecting workers from damages caused by any work-related accidents [20]. Health and safety “concerned with preserving and protecting human resources in the workplace” [44]. Employees who find the working environment safe will have a feeling of being cherished and cared for and might perform with loyalty and satisfaction. Employees are considered to be essential and the most precious asset of every academic institution for achieving its goals. They are highly influenced by the CSR initiatives carried through by the organization. Thus, they need to express their concerns about health and safety work conditions. It is the responsibility of the institution to prevent illness and deaths among its internal stakeholders (i.e., employees).

From the Ghanaian perspective, the conditions of service in Ghanaian universities state that a healthy and safe working environment must be ensured [45]. Ref. [46] explained that the work environment could be physical and psychosocial. The physical working environment relates to equipment, building, lighting, climate, noise, and radiation. The psychosocial working environment deals with employees’ integrity and dignity, accessible communication with other colleagues, and employees’ safety. Thus, no molestation and any other improper conduct. Health and safety improve organizational efficiency, quality of work, and good performance. So, any organization that does not invest in employees’ effective health and safety may suffer negative consequences such as high absenteeism, low productivity, and poor performance.

2.2.2. Human Rights

The United Nations Human Rights defines human rights as “rights that identify every human being’s inherent value regardless of background, nationality, place of residence, ethnic origin, sex, religion, language, and any other status”. Human rights are established on equality, mutual respect, and dignity, common in religions and cultures. It is all about making sincere choices, treating others fairly, and being treated relatively well [47]. Ref. [48] stated that ethics deal with what is right, fair, just, and good. Thus, organizations that engage in moral or ethical behavior generate a source of desire for internal stakeholders, enhancing their job performance, commitment, and satisfaction to the organization’s benefit. This is in line with the study by [49], in which it was proposed that the internal and external corporate ethics dimensions positively related to collective organizational commitment towards social performance.

For instance, in HEIs, most of the administrative staff are considered as front liners. Therefore, it is assumed that whenever they feel their human rights are respected, valued, and treated fairly by the institution, their trust for the institution would be developed. Build-up trust leads to good behavior and a positive attitude that can increase employees’ commitment and organizational performance.

2.2.3. Training and Development

There is a greater demand for a trained and skilled workforce in today’s competitive labor market. Training of employees does not only facilitate required technical and professional skills, but it also indicates that organizations are very much concerned about investing and providing employees a better chance for career development. Ref. [50] described training and development as when employees strengthen their existing knowledge, skills, and abilities through workshops, seminars, conferences, and other activities that motivate them to perform effectively at the workplace. By this notion, both training and development focus on developing employees’ skills, knowledge, and attitudes.

From the perspective of HEIs, most academic institutions’ strengths and development depend on staff training. Analytically, training becomes obligatory under each step of expansion and diversification so far as ICSR is concerned. So, staff needs to acquire the proper knowledge and improve their skills and abilities to perform better and increase productivity. Training and development are part of the learning process in the organization. Thus, it should be well designed, organized, and implemented to result in higher productivity and growth for sustainable competition.

2.2.4. Work-Life Balance

Work-life balance is one crucial facet of a healthy work environment. Ref. [51] explained that the work-life balance concept supports and enables workers to balance their time between work, family, and other personal issues. Work-life balance aims at cutting down employees’ work stress and grief since they spend more hours on work activities. For instance, chronic stress is a common health problem in the work environment. It can result in psychological and physical effects such as mental issues, depression, digestion problems, hypertension, body pains, insomnia, and heart-related pains. Hence, maintaining a work-life balance helps to decrease stress and burnout in the workplace.

Organizations like universities can effectively handle work-life balance by initiating flexible working conditions and provisions such as flexible work schedules, job sharing, company-sponsored family events, paid-time-off policies like personal days, vacation days, sick days, etc. [51,52]. Moreover, innovation and technology developments have made it possible for work tasks to be accomplished faster and simpler due to email, smartphones, video chat, and other technological software. Thus, organizations can use current technology at their workplace to facilitate individuals or employees to work flexibly without having to work overtime hours. If this is not done, it can lead to irritability, mood swings, and fatigue, which decreases work performance. Contrarily, if an organization creates a good working environment with work-life balance as a priority, it will save costs and preserve a healthier and productive workforce.

2.2.5. Workplace Diversity

In recent years, the development and improvement of workplace diversity have become an essential issue for organizational management due to the unusual change in the working environment. Workplace diversity relates to the workplace and refers to employees with varying characteristics such as different sex, gender, ethnicity, race, age, political ideologies, religion, language, educational background, physical abilities or socio-economic status, life experiences, and cognitive approaches toward problem-solving. Remarkably, workplace diversity does not just extend to hiring diverse individuals but also ensures that participation is equal among all employees.

Managing workplace diversity is still a challenge in many organizations. According to some business experts, workplace diversity is a huge challenge even though it has no limitations and does not know organizational boundaries. However, an organization that prioritizes diversity can widen its creativity, skill-base and become more innovative and competitive. Moreover, it will improve organizational effectiveness, productivity, and sustained competitiveness when organizations recognize and regard diversity.

2.3. Social Performance

Corporate social performance (CSP), also known as social performance (SP), has critically received empirical and theoretical attention for several years. This concept has been primarily used in business, society, and countries like the United States of America. Moreover, today’s practitioners and scholars are paying particular attention to the organization’s CSP—a concept that emphasizes an organization’s responsibility to employees, society, community, and traditional duties to economic shareholders [53,54]. CSP concept is an extension of the CSR concept that emphasizes results achieved [55]. According to [56], social performance is the practices, principles, and outcomes of a business relationship with institutions, organizations, communities, societies, people, and the globe regarding the planned activities of businesses towards these stakeholders and the unintended business externalities.

Similarly, CSP is “the configuration of the principles of business organization’s social responsibility, social responsiveness, processes, programs, policies, and observable outcomes as they relate to the firm’s human, stakeholder, and societal relationships” [57]. Wood’s definition further explained that to assess an organization’s social performance, the research scholar has to analyze the extent to which ethics of social responsibility influence actions perform on the organization’s behalf. The level to which the organization utilizes socially responsive processes, the presence and nature of programs and policies planned to manage the organization’s relationships, and observable outcomes that matter most to the organization’s actions, programs, and policies. Thus, the researcher’s efforts to analyze and examine social performance relate to principles, processes, and outcomes.

Some research scholars have developed a CSP model that helps determine if an organization is responsible for its economic and legal stakeholders and becomes socially responsible. Their model is a three-dimensional model for stress-free interpretation by managers of organizations. They are social responsibility categories, modes of social responsiveness, and social issues of stakeholders. For instance, the model by [56] on CSP provides a system’s approach to understanding CSP. The author established three CSR principles in the CSP model, which describe structural relationships between corporations, societies, and people. They are institutional legitimacy, public responsibility, and managerial discretion. The institutional legitimacy principle explains that society gives power and legitimacy to business organizations and that organizations must responsibly utilize their power to the community. The public responsibility principle also states that organizations take responsibility for any outcome related to their missions or societal participation areas. Every corporation has different responsibilities due to its size and operation. At the individual level of analysis, the managerial discretion principle emphasizes that managers are ethical actors who are obliged to use all the available discretion towards socially responsible outcomes. Thus, an individual’s right and responsibility to decide and take action are affirmed in the boundaries of economic, legal, and ethical constraints.

Secondly, corporate social responsiveness processes are boundary-spanning behaviors that help firms connect social responsibility principles to behavioral outcomes. The three primary facets of responsiveness are environmental assessment, stakeholder, and issues management.

Lastly, the outcome of corporate behavior directly affects the assessment of CSP. Policies, programs, and observable outcomes are related to the company’s social relationship. Outcomes are categorized into three kinds: the social effects of corporate behavior irrespective of the motivation for such behavior to occur; the policies corporations use to implement responsiveness; and the strategies developed by businesses to manage stakeholders’ interests and social concerns. One significant assumption of CSP is wide-ranging results from corporate conduct or behavior irrespective of its intent or knowledge of the firm. Thus, essential outcomes of CSP include profits, share value, returns on investment, and market share. It also provides stakeholder and socially significant outcomes like human rights concerns, workplace safety, utilization of natural resources, corruption, pollution, and effects on communities.

In another perspective, ref. [19], explained the CSP model as an organization’s economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities to society. Carroll stated that business institutions such as industries, firms, and organizations have relevant economic responsibilities that naturally occupy managers’ attention. Carroll’s model is theoretically less helpful. However, it reflects how managers perceive their CSR and performance better. Ref. [58], in a later study, stated that the attention on social performance gives rise to corporate actions and achievement in the social scope. Therefore, from the perspective of performance, it is evident that organizations must implement policies on social objectives programs and incorporate ethical responsiveness into the decision-making process.

We refer to social performance as an operative and effective transformation of an organization’s mission and accepted social values into practice to make its mission a reality. Every HEIs in Ghana has its mission in which it operates. For instance, the University of Ghana’s mission is to “create a conducive environment that makes the University increasingly important to national and international development through cutting-edge research as well as high teaching and learning”. In this regard, creating an enabling environment must include the wellbeing, social needs, and satisfaction of all stakeholders, including employees in the institution. Organizations must efficiently and effectively manage its social performance carefully and deliberately as it also operates their ICSR to achieve a solid social performance. Thus, CSP is a multi-dimensional concept that includes employees’ organizational activities, workplace diversity, the natural environment, customers, products, etc. [59]. Practically, it is a general template for evaluating how businesses identify and fulfill their responsibilities to individuals, stakeholders, and societies.

2.4. CSR in Higher Education Institutions

Higher learning institutions, which is also the knowledge sharing center, play an essential role in the social development and economic growth of society and contribute to stakeholders’ welfare. CSR in higher learning institutions or universities must represent an important area of impact and be an essential function of the universities. As a corporate entity, a university sets up its strategic policies, structures, and critical process to accomplish its long-term success. Moreover, it has many stakeholders such as employees, students, communities, government, institutions, and partner companies. The universities have a broad scope of social responsibilities. Therefore, their aim must be beneficial to society [60] since they are the society’s pillar beyond their supportiveness to economic growth [61]. As a result, ref. [62] suggested that embracing CSR is an appropriate strategy for HEIs to develop their responsibility as corporate citizens for all stakeholders.

CSR should be identified as a significant characteristic of HEIs and must be embedded with their policies. It is one of the university’s primary functions, and therefore it cannot be considered different as used in other manufacturing-based organizations. It is a management strategy used to manage both its internal and external dimensions and maintain its reputation outside the university [63]. Universities also have an immediate and direct influence on society, and hence the implementation of CSR strategies must be considered to achieve a positive reputation and a true competitive advantage. Usually, universities follow directives from society. Thus, the fundamental commitment of universities to society is teaching and research. Universities hold the primary responsibility by providing education and research in their communities and a rising number of entities pursuing higher education. By implication, the institution’s curricula repute and quality become a distinctive factor for their success [64]. However, HEIs have greater accountability beyond teaching and research. They have a broader task in human and social development to be responsible to all stakeholders by reinforcing their relationship with them [65,66].

Ref. [67] explained that CSR improves continuous development in higher education institutions with internal capacity and external impact, performance, and management. It helps the HEIs attract skilled employees and excellent students, yielding benefits in submitting a balanced report in the economic environment, social performance, and operations. It is necessary for university management to actively implement and support social activities responsibly and reflect its image and reputation.

2.5. Organizational Commitment and Social Performance

Organizational commitment is an essential employee attitude that can be related to organizational outcomes. One way employees exhibit positive behavior to their employer is through organizational commitment. While [68] emphasized the strategic importance of CSR for organizational success, other researchers such as [69,70] identified the significance of ICSR activities on employee commitment [71,72]. Importantly, ICSR practices of an organization could build a robust employer-employee relationship to achieve a strong employee commitment [73], which leads to better social performance [74]. Today, many organizations still recognize CSR to reinforce their relationships with stakeholders to ensure good interaction and total commitment. However, it is important to emphasize that it is unlikely to dissociate organizational commitment from corporate social performance due to their relatedness to CSR.

CSP is looked at in terms of outcomes in a social sense when considering organizational strategic goals. For instance, studies have revealed that employees’ behaviors and attitudes have some implications for organizational social performance, ultimately impacting overall performance [75]. Other researchers have argued that employees’ perception of positive social performance can result in employees’ positive attitudes and behavior [76,77,78]. Ref. [75] suggested that an organization’s social performance, for instance, environmental and community-relatedness, can influence employee commitment. They explained that social performance could create a good impression about the organization, making employees satisfied and proud to work for the organization and be more committed to it. In this sense, HEIs can also effectively implement ICSR practices to boost staff commitment to higher social performance.

2.6. Social Exchange Theory (SET)

According to [79], social exchange theory (SET) is a robust and theoretical framework for understanding business organization behavior. Ref. [80] offered a detailed conceptual framework to comprehend the employee-organization relationship. Their framework has received wider attention in the existing literature. However, social exchange theory is an economic and psychological way of human behavior that explains how people use it to create and maintain relationships with friends, families, strangers, and colleagues. Essentially, SET is a cost-benefit analysis that assesses the rewards and risks of continuing or pursuing a relationship. This theory is used to explain the actions of people in different settings and a multitude of relationships. SET can be applied to the workplace in both academic theory and practice. Thus, the employer-employee relationship is one of the key indicators of an organization’s success. If employees do not have a cordial relationship with each other at work, they will likely leave the organization and seek such good rapport elsewhere. Business organizations can use SET to structure company culture and workplace environment that promotes friendship and team building to help employees feel connected to the organization personally. Ref. [79] suggested that applying SET to a specific organizational context will enable employees to form a distinct social exchange relationship with their superiors, colleagues, customers, and suppliers. However, these relationships have insinuations for positive behavior.

SET supposes that when people get socioemotional and economic resources from their organization, they are likely to return with positive behavior and attitude [81]. Therefore, any form of exchange relationship requires either economic or social resources. According to [16], the norm of reciprocity is associated with the SET. Thus, employees may reciprocate the voluntary benefits and other resources (financial and socio-emotional) such as respect, care, and loyalty received from their organization. Moreover, according to this theory, organizational commitment resulting in positive behavior is developed when mutual exchange occurs. Thus, one partner contributes and expects that the other partner creates a sense of responsibility to reciprocate [71]. Further research proposes that when employees are valued and cared for by their organizations, there would eventually be a reciprocal through organizational commitment [71,82]. Obviously, ICSR relates to social performance via commitment based on the theory of social exchange.

3. Hypothesis and Research Framework

3.1. Internal CSR and Social Performance

CSR highlights the role of organizations within the development of the encircling community [83]. Moreover, it can become a decent means of accomplishing higher performance and competitive advantage [84]. Internal CSR may be an essential result of many organization’s success based on policies and practices that are reliable with the organization’s resources. It also represents an organization’s coherent tactics towards protecting its resources and providing employees with better quality of life. Organizations consider the impacts of their ICSR programs on organizational performance as well as internal stakeholder activity [85], and suggest a technique that integrates economic, social, and environmental factors in the organization’s strategy to improve social performance.

Measuring corporate social performance in some institutions such as HEIs must involve indicators that evaluate employees working conditions, relationships established with primary stakeholders like students, shareholders, and the local community. Ref. [86] explained that the analysis of social performance must consider other dimensions like the organization’s relationship with the employees, the community, the human rights, environmental impact, variety of social programs, and the extent to which the organization’s products meet both ecological and social standards. However, this agrees with the explanation of social performance by [56], which is the practices, principles, and outcomes of a business’ relationship with institutions, organizations, communities, societies, and people in terms of the deliberate activities of businesses towards these stakeholders.

Employees are important stakeholders, not only with the implementation of CSR initiatives but also with how the organization’s CSR strategy affects them. Therefore, it is imperative for organizations to ensure a cordial relationship between employees and top-level management. The organization also takes up the responsibility to put up structures for employees to collaborate with and other stakeholders. Furthermore, ICSR models mainly emphasize management support and organizational performance [85]. Thus, evolving and precise structures and instruments to access social performance facilitate communication with employees [87]. Using an integrative model makes it conceivable to concentrate on CSR practices in daily businesses with stakeholders [88]. Ref. [89] stated that for organizations to generate maximum benefits from CSR implementation models, employees play a key role in decision-making concerning which actions need to be undertaken. As ICSR activities influence more employees, the higher their commitment will be towards work. This effort improves their productivity and eventually positively influences organizational performance. According to [90], ICSR practices have positive effects on organizational performance through the establishment of a positive relationship with employees which will result in good decision making.

Internal CSR can enhance employee involvement, engagement, and identification in an organization. To derive optimal benefits from ICSR, ref. [91] proposed that CSR should be clustered into four categories, namely: health and safety, employee skills, the wellbeing of employees, and social equity. These components have been a source of doubt among employees and a source of contradiction between employers and employees [92]. Improving social performance has been a significant concern for stakeholders [93]. Therefore, an organization’s ability to reduce this misfeeling on these CSR initiatives can obtain higher productivity as well as organizational performance. As seen in the research of [94], ICSR activities have a positive impact on organizational social performance. Based on the reviewed literature, this study proposes the following hypotheses in Table 1.

Table 1.

Development of Hypothesis.

3.2. Research Framework

An organization’s social responsibility is one of the plausible grounds to build and improve a cordial relationship between its employees and the community. Internal CSR is described as how organizations or businesses respond to their social responsibilities regarding their employees. It is a concern with the social activities that directly connect with psychological and physical work conditions in the organization where employees find themselves. From the extant literature, internal CSR activities are discussed and analyzed at the organizational and individual levels [95,96]. The organizational level of ICSR initiatives focuses on the work environment that involves policies that aim at improving employees’ physical environment, including eradicating work environment risks that might threaten their health and safety. The individual’s level also focuses on employees directly and addresses their particular needs, which include programs for professional and skill development that satisfy their desires beyond the place of work.

In higher educational institutions (HEIs), employees are the main integral part of the overall process and development of quality educational standards. The extent of interaction and collaboration between the top-level management of institutions and employees is critical for assessing ICSR outcomes on social performance. For example, employees expect to have a sound working environment, good working tools, welfare programs, and quality infrastructure. This suggests that if there is an amicable relationship between management and the employees, there is the likelihood of positive outcomes via the principles and processes put in place by top management to increase institutional social performance. Such efforts by top management of HEIs promote organic solidarity to enhance academic excellence.

Generally, social activities and practices such as health and safety, training and development, human rights, workplace diversity, work-life balance, and other factors adopted by the top-level management and the human resource department are expected to motivate employees and increase satisfaction and commitment. Thus, employees can have a positive attitude towards their work to increase social performance. In other words, when the organization takes care of the employees’ needs and wellbeing, it creates opportunities for self-motivation, satisfaction, and comfort in the working environment.

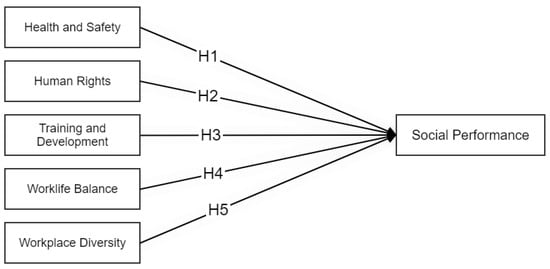

Interestingly, effective management of ICSR activities can give the institution a competitive advantage where the institution could maintain a better workforce to sustain instructional performance. The theoretical model in Figure 1 shows the link between ICSR activities and social performance. Thus, it explains how a higher educational institution can effectively consider and manage employees’ social needs and wellbeing to impact the institution’s social performance.

Figure 1.

Framework for Internal CSR activities and Social Performance.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

A descriptive and exploratory research design was adopted to find out and understand issues relating to ICSR and social performance in Ghanaian Universities. As part of the research design strategy, the multi-case approach was used because of the need to assess CSR activities in private and public Ghanaian universities. We purposely selected three public universities and one private university. The public universities are the University of Education, Winneba (UEW), the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), and Kumasi Technical University and the private university is the Christian Service University. One main reason for choosing these four universities was the differences in their settings and academic mandates, which reflects their assessment and implementation of ICSR initiatives. While the KNUST has the mandate to produce graduates to serve the science, technology, and engineering-related industries, the UEW produces professional teachers to teach in the Colleges of Education. Kumasi Technical University also has the primary mandate to train students to acquire skills to serve the technical and vocational industries, while the Christian Service University trains students in theology and other humanities to offer service to the community, including the service industry.

Thus, the survey comprised staff from both teaching and non-teaching of the selected universities. The list of the participants used for the study was obtained from the Human Resources Department of each university. The teaching staff comprised of senior members such as professors, senior lecturers, lecturers, and assistant lecturers. The non-teaching staff also consisted of senior members, senior and junior staff, including staff such as registrars, assistant registrars, finance officers, procurement officers and office administrators, lab technicians, transport officers, security officers, and cleaners. It must be emphasized that in all the four universities, the non-teaching staff outnumbered the teaching staff. This was evidenced by the list of staff we obtained from the Division of Human Resources of each university. Hence, the study considered relatively more non-teaching staff than teaching staff in proportionate terms.

We used a stratified sampling technique to categorize the population into teaching and non-teaching staff. Further, a systematic sampling technique was used to select from each stratum the required number of respondents. Hence, a total sample size of 492 respondents was selected. Of the 492 respondents, 159 respondents were teaching staff, and 333 respondents were non-teaching staff.

We employed a mixed technique to analyze the significant relationships between ICSR activities and social performance in higher learning institutions. Thus, both quantitative and qualitative techniques were used to analyze behaviors, events, and some significant phenomena that need to be explained regarding ICSR and its impact on social performance. These techniques allowed for detailed investigation and understanding of how internal CSR activities impact social performance in these universities. Ref. [97] explains that descriptive research may not be sufficient to bring out all elements of a study, so there was the need to quantify research indicators and the things they stand to explain at all events.

For the data collection procedure, the study used structured questionnaires to collect data from the respondents. Out of 600 questionnaires sent to the respondents, 512 responses were returned, but 492 responses were usable, representing 82% response rate. Participants were reminded two weeks later through emails about the completion of the questionnaires. Before administering the questionnaires, a pilot test was conducted to ensure face reliability, validity, consistency, and accuracy of the items in the questionnaire. This was done to avoid responses that would impact the results of the study negatively. In view of this, five staff were selected from each university to participate in the pilot exercise. Obviously, there were lapses and some irrelevant items in the questionnaire, and these were corrected. Moreover, we did a thorough review of existing literature to understand the area under investigation, especially the developmental trends in ICSR activities relative to social performance as a measure of organizational success. This helped define the problem domain very well, including the instruments appropriate for the research’s conduct.

The study used structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze the data and test the hypotheses. Given similar empirical studies that employed SEM, it was justified to use SEM to ensure the fittingness of the data to the research model. In addition, we used Pearson Correlation and Multiple Linear Regression Analyses to analyze the data to identify relevant correlations between the constructs and the effects of internal CSR activities on social performance. Though the non-teaching staff was relatively more than the teaching staff, there were no significant biases that affected the outcomes of this study. In other words, the results of the analysis showed some significant relationships between each measure and social performance.

4.2. Measurement

The main constructs in this study were five dimensions of ICSR and social performance. The measurement items of all constructs have been tested and used in CSR literature. Precisely, all the dimensions of ICSR were measured with 36 items adapted from [72], the social performance was measured with 20 items adapted from previous literature [98]. We used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) for all questionnaire items.

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 and Table 3 show the demographic information of the sampled universities and the respondents used. Out of the 492 respondents from the four universities, 27.7%, 28.7%, 22.8%, and 20.9% were from KNUST, UEW, Kumasi Technical University, and the Christian Service University, respectively. Males and females within the selected academic institutions constituted 58.5% and 41.5%, respectively. The age of the responders’ were 1.4%, 9.3%, 19.9%, 32.1%, and 37.2% between 21–26 years, 26–30 years, 31–35 years, 36–40 years, and over 40 years, respectively. More than half of the respondents (79.3%) were married, 17.5 were single, 0.0% were divorced, and 3.3% were widowed. Of the respondents, 9.6%, 2.4%, 21.7%, 45.1%, and 21.1% had acquired advanced diploma certificates, bachelor’s degrees, master’s degrees, and doctorates, respectively. In terms of work experience, 6.3%, 18.7%, 11.8%, 10.2%, and 53.0% had worked in the university for less than a year, between 2–3 years, between 3–4 years, between 5–6 years, and more than 7 years respectively. Lastly, 12.6%, 47.0%, 8.1%, 27.0%, and 5.3% of employees were Junior Staff, Senior Staff, Registrars, Lecturers, and Professors, respectively.

Table 2.

Composition of the sample universities.

Table 3.

Sample characteristics of respondents.

5.2. Reliability and Validity Measure

The reliability of the variables was conducted with Cronbach Alpha values to check the consistency and internal stability. Table 4 below shows the values of Cronbach Alpha for all the constructs. It shows that Cronbach’s Alpha values range from 0.570 to 0.952. This indicates an acceptable reliability level.

Table 4.

Reliability of Scales and Cronbach Alpha of Variables.

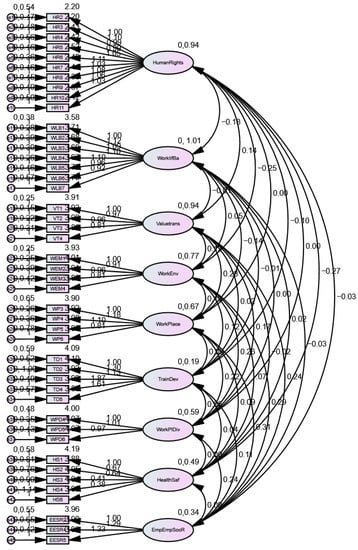

Moreover, ref. [99]’s factor analysis was used. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed to test the validity and confirm the latent variables’ factor structure. As a result, factor loadings of some measurement items recorded below the accepted values and these were removed. Eventually, the data were apposite for factor analysis as the KMO showed 0.867, which was higher than the threshold value of 0.60. This showed that every item of the construct has a significant correlation with a high level of validity. The overall significant relationship between all variables was adequate with Bartlett’s Sphericity evaluation with a p-value < 0.001. Table 5 details the study’s constructs with factor loadings, eigenvalues, explanation of variance, and cumulative variance. Thus, the factor analysis yielded nine components with 61.62% of the total variance. At least, all the questions had good loadings on the constructs. Using Amos software, EFA was conducted, and the measurement model is shown in Figure 2.

Table 5.

Validity of items.

Figure 2.

Measurement Model.

For common method variance, we used Harman’s single factor test approach for the initial assessment, and the test indicated no significant bias. The computed variance (14.82%) did not exceed the threshold value of 50%. Hence, there was no correction needed theoretically. It must be emphasized that the single factor test approach was made for thoroughness purposes. Endogeneity issues might also be significantly reduced when meaningful and coherent control variables are examined. We, therefore, recognized and discussed the possible endogeneity issues by comparing the results of our model before and after the introduction of the control variables; there was no significant difference in the results. This suggested that the problem of endogeneity was minimized and did not impact the overall outcomes for the study.

Means and standard deviations were computed to explain the degree to which respondents reacted to instrument items. Ref. [72] categorized the mean value of all variables into three levels of responses as low, moderate, and high. They stated that any mean value less than 2.00 is considered low, a mean value between 2.00 and less than 3.50 as moderate, and mean values of 3.5 or higher as a high level of responses. Table 6 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations for the five dimensions of ICSR and social performance. The mean values indicated that Ghana’s universities focus on health and safety, followed by workplace diversity, training and development, work-life balance, and human rights. This showed that some universities in Ghana had adopted ICSR practices on average (mean = 3.47 and standard deviation = 1.117). However, there was high social performance within the universities (mean = 3.93 and standard deviation = 1.042).

Table 6.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

The correlation between the ICSR and social performance gave an overview of possible relationships between the variables and to identify the multicollinearity among the study variables. Thus, health and safety (r = 0.169, p < 0.01), training and development (r = 0.330, p < 0.01), and workplace diversity (r = 0.545, p < 0.01) had a positive and moderate significant relationship with social performance. Workplace diversity had a strong correlation with social performance. These results indicate significant relationships. Therefore, hypotheses H1, H3, and H5 were accepted. This means that when organizations adopted these ICSR dimensions more positively, their social performance increased. This outcome supports the findings by [100]. However, two ICSR dimensions; human rights (r = −0.065 p < 0.01) and work-life balance (r = −0.057, p < 0.01) had a negative and insignificant relationship with social performance. This result showed no significant relationship between the two variables (human rights and work-life balance) and social performance. Hence, hypotheses H2 and H4 were rejected.

Further, we analyzed the level of impact of the five dimensions of ICSR (independent variables) on the social performance (dependent variable) of HEIs in Ghana. From Table 7, the R statistic of 0.610 indicated a moderate correlation between ICSR variables and social performance. The R2 value of 0.372 showed that the five predictors collectively contributed to 37.2% of the variation. Thus, the independent variables (health and safety, human rights, training and development, work-life balance, and workplace diversity) could only explain about 37.2% by the variabilities in the dependent variables (social performance). Further, the F value of 57.570 (p < 0.05) was statistically significant. The t-value for health and safety, training and development, and workplace diversity have a significant level of 0.05, signifying that these three ICSR dimensions have a positive and significant correlation with social performance.

Table 7.

Model Summary.

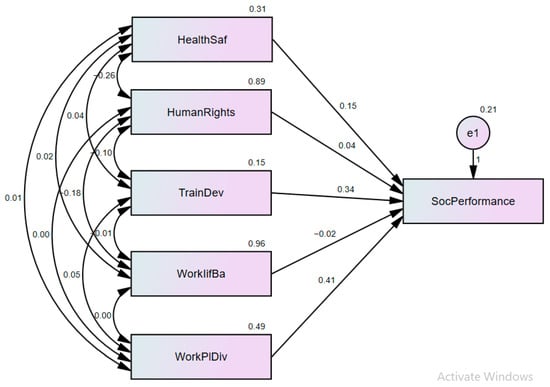

Moreover, workplace diversity influenced up to 50.1% of social performance, which indicated that it is an important variable to impact organizational social performance, followed by training and development (22.9%), health and safety (15.1%), human rights (6.7%), and work-life balance (−4.2%). The Structural model, which depicts correlation among the constructs, is shown in Figure 3. It includes the estimates of the path coefficient and the R-squared value, determining the model’s predictive power.

Figure 3.

Structural Model.

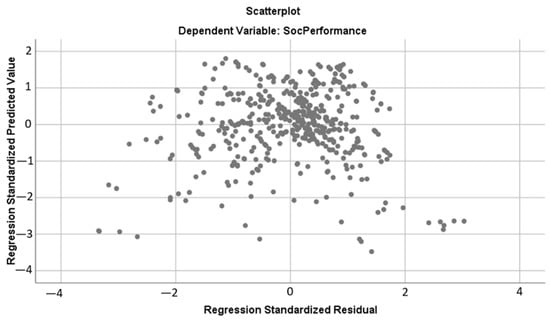

There was a moderate positive correlation between the dependent and independent variables. Thus, an increase in ICSR activities would lead to high social performance (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Scatterplot showing Residual against Predicted Values.

6. Discussion

This study’s primary purpose was to empirically investigate the impact of ICSR activities on social performance in the HEIs in Ghana. The results confirmed that only three ICSR dimensions (health and safety, training and development, and workplace diversity) positively and significantly impacted social performance. At the same time, human rights and work-life balance had an insignificant effect on social performance. Ref. [75] suggested that an organization’s social performance, for instance, environmentally and community-related, can influence employee commitment. Therefore, this finding is partially in tandem with the study by [100], which examined ICSR and employees’ organizational commitment in some Vietnamese service firms. Their results established that health and safety, training and development, and labor union were significantly related to organizational commitment, which increases the social performance of an organization. However, in their study, the work-life balance and social dialogue had an insignificant correlation with organizational commitment, affecting organizational social performance negatively. They concluded that most service firms’ efforts are inadequate when considering work-life balance and social dialogue in their ICSR implementation. Their study recommended that service firms improve and reinforce those initiatives for the benefit of employees.

This study found that health and safety had a positive and significant relationship with organizational social performance (β = 0.151, p < 0.05). This means that the more efforts management of HEIs puts in promoting health and safety in their work activities, the higher social performance increases in the institution. This finding is consistent with the results of [43,72,101] and [102] that attested that health and safety has a positive and significant relationship on commitment as well as organizational performance. Ref. [103] specified that a favorable working environment considered by an employer for its employees’ health and safety issues will enhance employees’ commitment towards organizational performance. When an institution provides employees with a conducive and safe working environment, employees will be motivated and will likely commit to hard work towards their job. This kind of attitude can effectively and efficiently improve the social performance of the institution. Further scrutiny of health and safety by researchers can bring out other relevant attributes that organizations have to consider when analyzing the activities involved in health and safety and their impact on social performance

Human rights have a positive and non-significant relationship with social performance (β = 0.067, p < 0.05). However, we found that there is an insignificant correlation between human rights and social performance. This finding is inconsistent with [104] study, which found human rights correlating with organizational performance through social performance. Ref. [72] examined the relationship between five dimensions of ICSR (human rights, training and development, health and safety, workplace diversity, and work-life balance) and organizational commitment within Jordan’s banking sector. The results showed that human rights had a positive and significant relationship with affective and normative commitment but did not correlated with continuance commitment. However, per the constitution of Ghana, everybody has freedom of speech, but this right has not descended into the HEIs. By implication, many efforts are required to guarantee employees their rights as both humans and respect for their dignity in the work environment. An HEI that neglects the rights of its employees creates a work syndrome of employee turnover and retention. Hence, the management of HEIs is to be mindful of employees’ rights and dignity. Further, researchers can crusade on the rights of employees by deepening the understanding of not only the roles of employees’ unions but also the rights to elevate the psychological and mental freedom duly associated with the discharge of duties at the workplace.

Furthermore, this study’s outcome revealed that training and development had a significant positive relationship with social performance (β = 0.229, p < 0.05). This implies that training and development is an important factor to keep employees and an essential indicator for organizational social performance. Employees who perceive their institution as caring and supportive about their wellbeing by giving them opportunities to develop their skills and help address their personal development are likely to exhibit a positive attitude towards work. Moreover, staff retention is high when the institution is more concerned about staff development by providing adequate skill training, which helps them develop competencies and abilities that enhance their proficiencies and performance. This finding is consistent with the study by [105], which suggested that staff perceive occupational development opportunities as a kind of institutional support that leads to higher organizational social performance. This outcome is also in line with the study by [106], which revealed that training and development allowed academic staff to develop indispensable knowledge, skills, abilities, and competencies. Undoubtedly, this finding suggests to the management of HEIs that there is a need for substantial allocation of resources to increase training and development if the institution intends to significantly increase social performance for quality outcomes. Besides, researchers can investigate specific attributes of the kinds of training and development fundamental to enhancing employees’ competencies and skills for higher job productivity in higher educational institutions. Hence, it is crucial to note that employees’ well-being towards organizations has a great link with training and academic development offered by the HEIs.

Contrary to the research hypothesis, work-life balance was seen to have a negative and no significant effect on social performance (β = −0.042, p < 0.05). This outcome is similar to the work by [100], whose study found that work-life balance had no significant relationship with organizational commitment, leading to an organization’s higher productivity. A possible reason could be that HEIs’ efforts concerning their ICSR activities for work-life balance were inadequate. Thus, the absence of work-life balance can lead to low performance and productivity [107]. Impliedly, top management of HEIs can analyze thoroughly those factors contributing to the disparity in work-life balance among employees. For instance, if employees are unable to have a balance between hours spent at the work and other personal, socially-related lifestyle, they become quite aggrieved towards their jobs, which ultimately impact job performance negatively. Moreover, researchers have the responsibility to examine critically job design, structure, and process of accomplishment to determine whether or not employees are achieving optimal work-life balance.

Workplace diversity also had a positive and significant relationship with social performance (β = −0.501, p < 0.05). Essentially, an institution that emphasizes diversity in the work environment, such as providing equal opportunities to employees regardless of gender, race, and religion, can increase social performance. This is supported by previous work by [108], which revealed that when an organization implements diversity management, it makes employees aware that the organization is committed to satisfying the diverse needs and welfare of employees. Consequently, employees’ commitment to the job can lead to high social performance. However, employees’ commitment can be improved via group training of the organization’s diverse workforce and team building. Fair treatment concerning equal opportunities for rewards and promotion can make employees cherish corporate values and exhibit a positive attitude towards the institution. Essentially, when HEIs succeed in managing workplace diversity, they can establish relations and connections with their staff by making them experience a personal level of interaction and consider each employee’s status. This will result in an intelligent workforce that the institution appreciates, cares for, and respects, and employees will feel valued and comfortable in their job, leading to higher social performance. However, a diversified work environment suggests an interplay with culture, which can sometimes challenge shared vision and norms. Past studies have shown that organizational or institutional culture plays a contributive role in the overall social performance and hence job productivity. This finding also draws attention to researchers in considering the link between employee relation and work environment initiatives.

7. Implications of the Study

7.1. Theoretical Implications

The connection between organizational social performance and employees’ work attitudes remained a challenge to researchers [109]. However, this study attempted to bridge the gap by employing social exchange theory (SET) to give profound insights into employees’ behavior and attitude and their effects on overall corporate social performance through ICSR activities. All the ICSR dimensions in this study represent the socio-emotional resources except for a few human rights items, representing economic resources like salary.

The findings of the study showed that three of the constructs have a significant impact on social performance. This connotes that SET, which involves economic and socioemotional resources, is the foremost reasonable way to clarify the reciprocal effect of ICSR activities on social performance through positive employee behavior. This supports earlier studies applying SET to illustrate the reciprocal relationship between organizational activities and employee behavior. Thus, this study contributes to the literature by assessing the effects of ICSR activities on corporate social performance, especially in HEIs. Further, it serves as a springboard for future studies concerning the relationship between ICSR activities and corporate social performance in HEIs.

7.2. Managerial Implications

Top-level management in HEIs is encouraged to pay particular attention and constantly review the five essential dimensions of ICSR activities in their institutions. When staff feel respected, valued, and concerned by the institution, they demonstrate loyalty and commitment to the institution. In addition, organizations should ascertain an autonomous CSR department for both internal and external CSR to be implemented and monitored effectively and efficiently. The human resource department can also be informed by top management to recognize the importance of ICSR, such as improving training and development, safe working environment, better workplace diversity, proper work-life balance, practices, and high productivity policies for the success of the organization.

Moreover, this study revealed workplace diversity as the most influential and significant variable impacting an organization’s social performance. Therefore, the management of HEIs must put much effort into every aspect of ICSR practices most desired by employees. For instance, management can improve career development strategies, offer various career advancement opportunities, and provide supportive research facilities. Finally, when academic institutions operate in an ethical manner such that procedures and policies are reliable, non-biased, and treat employees with respect and dignity, the staff might willingly repay the institution with a high commitment level which will significantly improve social performance.

8. Limitations and Future Research

Even though this research contributes much to CSR knowledge in academic institutions, particularly HEIs in Ghana, it has some limitations and will require further investigation.

First, the model of the research is limited to only five dimensions of ICSR activities. This implies that there are testable variables that can be examined or investigated in relation to corporate social performance. Such factors include rewards, promotion, remunerations, disable support, and job satisfaction. Hence, the five ICSR activities may not be the only factors to influence social performance. Future research can consider other factors such as those mentioned earlier and examine their impact on social performance to understand internal CSR activities and their dynamics.

Second, the questionnaires were distributed to only employees in the selected universities in Ghana. The findings of this study may not represent all employees in the many universities in Ghana. Therefore, additional studies in the future can target a broader scope of respondents from many HEIs in Ghana so that the results’ accuracy and reliability can be improved.

Last, the small sample size was a potential limitation since it was considered inadequate for the study regarding the numerous universities in Ghana. It is expected that future studies will increase the sample size to help advance the accuracy and generalization of the findings.

9. Conclusions

Internal CSR activities from the perspective of employees are a critical aspect of an organization’s social responsibility. This study focuses on CSR’s internal dimensions to determine its impact on social performance in the HEIs in Ghana. The study examined the effects of ICSR activities on social performance and how the dimensions significantly impact social performance. The empirical results showed that health and safety, training and development, and workplace diversity improve social performance in HEIs. Interestingly, workplace diversity highly affected social performance than the rest of the dimensions. The study deepens the understanding of the five dimensions of ICSR, especially in academic institutions where staff retention is mostly a priority. This suggests that social performance increases if management in HEIs realizes the need to address issues relating to these five dimensions of ICSR. Such efforts by management reflect employees’ attitude, behavior, and commitment towards work positively. It is crucial for top management of HEIs to actively implement and support internal social responsibility practices to improve employees’ social wellbeing for increased organizational performance and elevate the institution’s image and reputation. Therefore, this study contributes to the existing literature with much emphasis on ICSR and social performance in the context of HEIs. Further, future works should investigate the other ICSR factors such as motivation, corporate reputation, and management leadership style and their effects on social performance for improved organizational performance.

Author Contributions

Writing of original draft, M.A.-G.; Conceptualization and supervision, Z.H.; Conceptualization, revision and editing, G.N.; Data analysis and interpretation, S.B.; Review and editing, M.F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kofi Amankwah-Sarpong for his comments and suggestions for improvement of the study. We thank Adasa Nkrumah Kofi Frimpong for organizing the data set. Similarly, we also appreciate Stephen Sarfo Adu-Yeboah and Millicent Amoah for their help and advice. Finally, we are grateful to Estela Zhang for her editorial comments and the two anonymous reviewers for their review comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Nelson, J.; Prescott, D. Business and the Millennium Development Goals: A Framework for Action. UNDP Int. Bus. Lead. Forum 2008, 2, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, K.T. The Advertising Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Reputation and Brand Equity: Evidence from the Life Insurance Industry in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Resource-Based Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A.; Sever, J.M. The Reputation QuotientSM: A Multi-Stakeholder Measure of Corporate Reputation. J. Brand Manag. 2000, 7, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Frenkel, S.J. Alternative Pathways to High-Performance Workplaces. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 1325–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Philanthropy’s New Agenda: Creating Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Competitive Advantage of Corporate Philanthropy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 56–69. [Google Scholar]