The Sustainability of Intangible Heritage in the COVID-19 Era—Resilience, Reinvention, and Challenges in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Issues and Research Questions

1.2. Hypothesis

- (1)

- On the one hand, this situation has led to major alterations to ICH festivities and practices and has disrupted community relations by limiting events that act as mechanisms for integration and social cohesion. Local communities have reacted with frustration and a sense of loss. In the same way, the effects on the economy are severe because of the implications for tourism, a lack of revenue for the craft sector that threatens to destroy it altogether, and the loss of income for organizing associations.

- (2)

- On the other hand, however, lockdown has prompted creativity and reinvention involving new forms, both face-to-face and virtual. Festivals and rituals, far from stopping altogether, have adapted to the new situation with alternative forms and have taken shape in a space negotiated between local communities and political authorities.

- (3)

- Moreover, during this time of social distancing, ICH has acted as an important means of providing social cohesion at a time of uncertainty and as a response to the overall experience of the pandemic.

- (4)

- For all these reasons, the pandemic crisis of COVID-19 has posed new challenges and strategies for communities seeking to hold festivities. This makes it necessary to redefine the social value of heritage and, above all, to propose new strategies for cultural sustainability.

1.3. Objectives

- (1)

- To analyze the social, economic, and political impact of public health restrictions and the cancellation of most festivities on ICH in Spain. Studying the impact of the cancellation of festive practices on communities allows us to analyze the significance and values of intangible heritage under exceptional circumstances.

- (2)

- To analyze the different responses of communities to the prohibition of events, and to describe and document alternative practices implemented that made it possible to continue holding events, in person or virtually.

- (3)

- To contribute to formulating a model for the future sustainability of ICH post-COVID-19, both from a theoretical and an applied perspective, providing matters for debate that should be taken into account by the organizing communities to ensure the continuity of ICH.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Analysis

- -

- Documents and reports on public health regulations, economic effects, impact on organizing associations, public announcements, etc;

- -

- Programs of alternative activities, news, and reports on events on websites of the different towns in which events are held;

- -

- Monitoring of the effect of COVID-19 in online discussions arranged by the various organizers of heritage elements. This was only possible in seven heritage elements that actually organized such debates (a total of 23 videos observed). We were particularly interested in the debates involving members of the organizing associations themselves who reported on their own experiences. In addition, the fact that these debates were recorded allowed us to see how they evolved over time as the constraints and perceptions of the social constraints developed;

- -

- Analysis of local and national press reports for each of the cases that reported on debates around the festivities and activities and statements made by public officials and the heads of associations;

- -

- Analysis of social networks (Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram) related to each of the ICH elements. In the case of Twitter, the mining and search for the information was conducted by means of the qualitative analysis software application Atlas-Ti and resulted in an analysis of 1840 messages related to these events throughout 2020. Since the contents of the networks are generally produced by the users themselves, they have the potential to “store” the circumstances experienced as they occurred, thus capturing the changing nature of ICH practices and the sequence of events and perceptions [26]. Analysis of these narratives enabled us to offset a potentially fossilized view of ICH representations [26].

2.2. Case Studies

2.3. The Elements on the UNESCO ICH Representative List in Spain

3. Results

3.1. Strategies Employed by Organizers of Intangible Heritage to Deal with COVID-19 Pandemic

- Cancellation of the festivity. Table 1 reveals that most of the festivities were cancelled during the first year of the pandemic. Generally speaking, official announcements stressed the exceptional circumstances and the need to protect health. For example, the president of the organizing committee of the Mystery of Elx pointed out that “it is with great regret that we have to communicate that is impossible to hold the Mystery of Elx this August. We are convinced that it is the best decision we can take from the point of view of public health and the safety of citizens”, adding that “we will continue our efforts to safeguard our World Heritage and continue to raise awareness of the event” [46].

- Change of date. Although this alternative was contemplated in a good number of cases (such as the Valencia fallas, the Pyrenean fire festivals, and the Berga Patum), in the end it was only adopted in one case: the Fiestas of Patios in Cordova were indeed moved from May to October, and were celebrated in a very similar format [47]. A change of dates was rarely applied, not only because it was not known how the pandemic would evolve, but also because the change implied disrupting the life of the community. In guidelines produced by the Ministry of Culture after lockdown was decreed [48], it was considered that “changes of dates should be prohibited”, because intangible cultural assets “are characterized by being closely linked to specific dates”, and “they are governed by temporal rhythms that are usually linked directly and inseparably to a particular season or specific date in the annual calendar”.

- Small-scale format. Some organizers opted for reduced formats, maintaining some elements that were considered symbolic or representative, rapidly reinventing the manner in which they were held, and moving the venues. For example, for the tamboradas (an intense, prolonged drumming for several hours in the town square during Easter Week), organizers in Hellín, Castile La Mancha proposed a token 10 min of drumming on people’s balconies [49], pointing out that this was done in “homage to the victims and those who are continuing to fight for our health and wellbeing”. Reports stated that “both children and adults drummed on their balconies, perpetuating our age-old tradition”. Regarding the Chant of the Sybil, which is performed at midnight mass in the churches of Mallorca, alternatives varied according to the location. This meant reducing numbers and moving the time to before curfews, while there were services with no congregation at all (in the Sanctuary of Lluc, for example). In the Pyrenean fire festivals, some municipalities also opted to limit celebrations to a few symbolic events or to allow villagers only. It is interesting to note two aspects of these small-scale celebrations: (1) the choice of certain acts considered “representative” enables us to see how the various elements are appreciated by the community, and (2) these acts are presented as a way of continuing the festival symbolically. For example, in the Tamborada of Vila-real (in the region of Valencia), where locals were able to beat their drums on their balconies, the mayor of the town explained that this continued the spirit of the celebration: “The inhabitants of Vila-real are proud of our traditions, of our identity and values and, of course, of our Easter Week. And we are not going to allow the pandemic to prevent us from enjoying and defending what is ours (...) and enjoying the festivity at home, with innovative initiatives” [50].

- Virtual events. The use of virtual space already has a long history in inventories adapted for the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage [19], but during the COVID-19 period, its use has increased considerably [8] and all the heritage elements analyzed in Spain resorted to carrying out some type of online activity.

3.2. Impact of the Pandemic on Intangible Heritage Practices

3.2.1. Preventive Measures, Social Distancing, and ICH Practices

3.2.2. Effects on Social Relations and Social Well-Being

3.2.3. Economic Effects

3.3. Case Studies

3.3.1. The Valencia Fallas

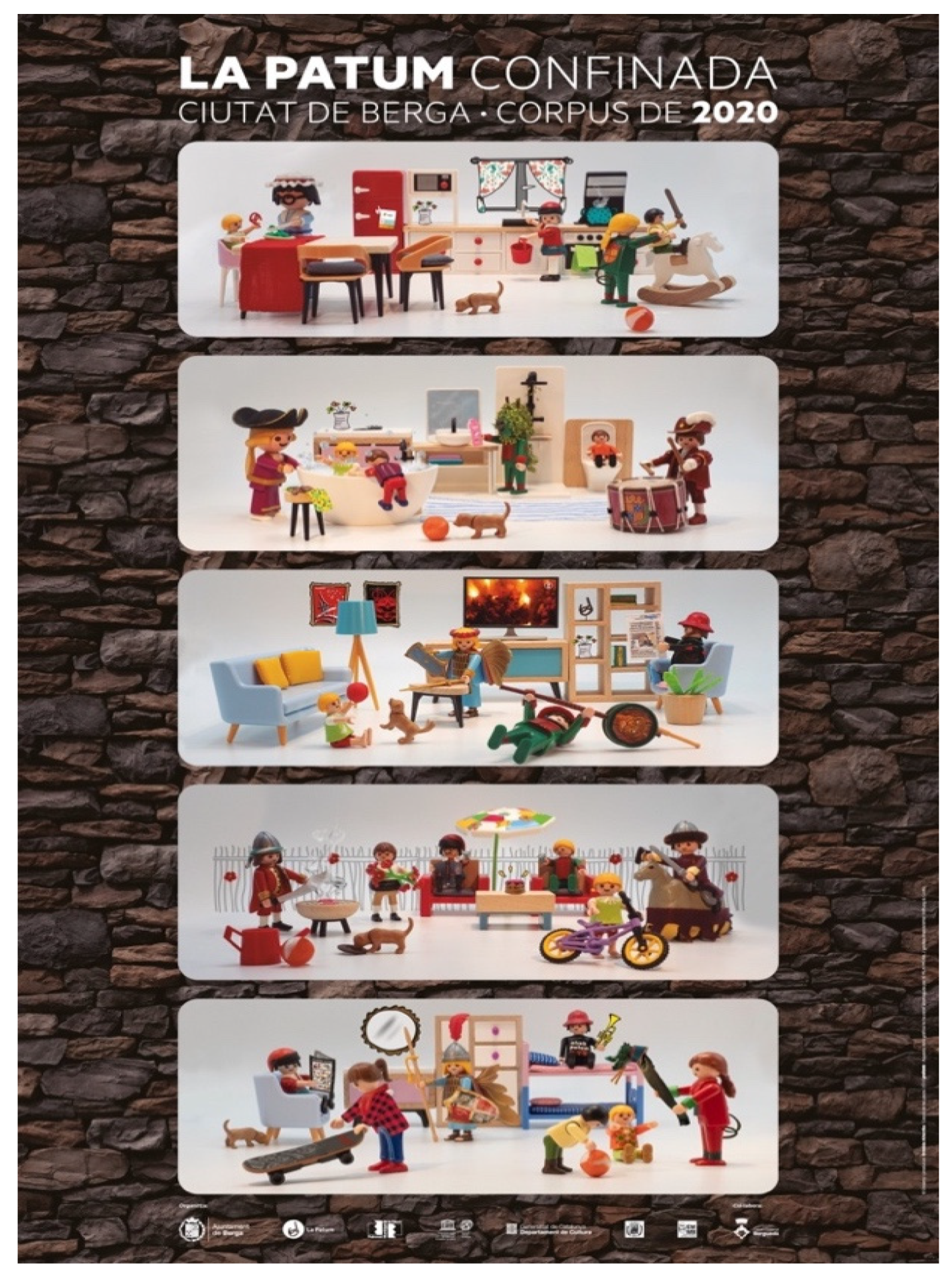

3.3.2. The Berga Patum

3.3.3. Human Towers (Castells) in Catalonia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- To a greater or lesser degree and depending on the type of heritage, the pandemic has had a major social and economic impact on ICH and on organizing associations. The cancellation of the festivities has shown the vulnerability of intangible heritage, a fragility that comes not so much from its intangibility, but from its links to the “bearers” [88], who are subject to the effects of the vicissitudes of social life, as has been seen in the pandemic period.

- Faced with the cancellation of the activities, local communities have proved to be more than capable of transforming ICH practices. The resilience and social cohesion seen in new social practices have been rooted in a discourse of tradition and the sense of belonging to places and communities. At the same time, the social value of ICH has been highlighted during the pandemic, acting as a collective glue and embodying meanings and values that are important to a community [99].

- Festival communities are concerned about the future of ICH. The post-COVID-19 era makes it necessary to rethink the cultural, economic, and social sustainability of ICH practices, especially festivals, by adopting cultural management models that ensure this occurs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davies, K. Festivals Post Covid-19. Leis. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imber-Black, E. Rituals in the Time of COVID-19: Imagination, Responsiveness, and the Human Spirit. Fam. Process 2020, 59, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, S.; Maguire, M. Public space during COVID-19. Soc. Anthropol. 2020, 28, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsalpara, C.; Soulopoulos, I.; Sklias, I.; Grammalidis, N. Covid-19 Pandemic’s Influence on Popular/Folk Culture and Tourism in Greece: Shaping the Future and Beyond. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism in the COVID-19; 9th ICSIMAT Conference 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, J. Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003). In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Intangible Cultural Heritage in Emergencies Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Addressing Questions of ICH and Resilience in Times of Crisis: Report; UNESCO Office Venice and Regional Bureau for Science and Culture in Europe: Venice, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bawidamann, L.; Peter, L.; Walthert, R. Restricted religion. Compliance, vicariousness, and authority during the Corona pandemic in Switzerland. Eur. Soc. 2020, 23 (Suppl. S1), S637–S657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roigé, X.; Bellas, L.; Soulier, V. El Museo Virtual de las Fiestas del Fuego del Pirineo. Un Museo en Línea a Partir del Patrimonio Inmaterial. In Proceedings of the I Congreso Internacional de Museos y Estrategias Digitales, Edicions Universitat de Valencia, Valencia, España, 22–26 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cantoni, L.; De Ascaniis, S.; Elgin-Nijhuis, K. Living heritage and sustainable tourism. In Proceedings of the HTHIC Conference, Università della Swizzera Italiana, Lugano, Switzerland, 25–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, J.; Lee, S.; Jamal, T. Indigenous Heritage Tourism Development in a (Post-) COVID World: Towards Social Justice at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, USA. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, X.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Sustainability of Heritage Tourism: A Structural Perspective from Cultural Identity and Consumption Intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, C. L’Unesco comme arène de traduction. La fabrique globale du patrimoine immatériel. Gradhiva 2013, 18, 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, W. Constructing new terminology for intangible cultural heritage. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, C. Le trouble du patrimoine culturel immatériel. Terrain 2011, 26, 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Intangible Heritage: A challenge to the authorised heritage discourse? Rev. Etnol. Catalunya 2015, 40, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Debarbieux, B.; Bortolotto, C.; Munz, H.; Raziano, C. Sharing heritage? Politics and territoriality in UNESCO’s heritage lists. Territ. Politics Gov. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, C. Globalising Intangible Cultural Heritage? Heritage and Globalization; Labadi, S., Long, C., Eds.; Routdlege: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, A. Rethinking the festival: Power and politics. Method Theory Study Relig. 2014, 26, 44–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominelli, F.; Greffe, X. Intangible cultural heritage: Safeguarding for creativity. Cult. Soc. 2012, 3, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuutma, K. Cultural identity, nationalism and changes in singing traditions. Folk. Electron. J. Folk. 1996, 2, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissevain, J. Notas sobre la renovación de las celebraciones populares públicas europeas. Arx. Sociol. 1999, 3, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Im, D.; Lee, J.; Choi, H. Utility of Digital Technologies for the Sustainability of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) in Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F. Map of e-Inventories of ICH. Mem. Rev. 2017, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schweibenz, W. The virtual museum: An overview of its origins, concepts, and terminology. Mus. Rev. 2019, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobruno, S. YouTube and the social archiving of intangible heritage. N. Media Soc. 2013, 15, 1259–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccardi, E. Heritage and Social Media: Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Giudici, C.; Dessì, C.; Pollnow, B.C. Is intangible cultural heritage able to promote sustainability in tourism? Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2013, 5, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Tourism, Heritage and Cultural Sustainability: Three Golden Rules. In Cultural Tourism and Sustainable Local Development; Fusco, L., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Arnham: Surrey, UK, 2009; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Cheng, W. The cultural tourism and the protection of intangible heritage. Hum. Geogr. 2008, 1, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Whitford, M.; Arcodia, C. Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: The intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.; Seño, F. Somos de marca. Turismo y marca UNESCO en el Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. Pasos 2019, 17, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.A.; Turner, R. Cultural Sustainability: A Framework for Relationships, Understanding, and Action. J. Am. Folk. 2020, 133, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.; Spitzer, N.R. Public Folklore; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Naguib, S.A. Museums, diasporas and the sustainability of intangible cultural heritage. Sustainability 2015, 5, 2178–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel-Bouchier, D. Cultural Heritage and the Challenge of Sustainability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the Scientific Discourse on Cultural Sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Culture, Economics, and Sustainability. J. Cult. Econ. 1995, 19, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, C. Virtual Ethnography; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, L.; Schulz, J. New Fieldsites, New Methods: New Ethnographic Opportunities. In The Handbook of Emergent Technologies in Social Research; Hesse-Biber, S.N., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, A.; Standlee, A.I.; Bechkoff, J.; Cui, Y. Ethnographic Approaches to the Internet and Computer-Mediated Communication. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2009, 38, 52–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. Doing Internet Research: Critical Issues and Methods for Examining the Net; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alivizatou, M. Digital Intangible Heritage: Inventories. Virtual Learning and Participation. Herit. Soc. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.; Martin, E.; Vesperi, M.D. An Anthropology of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anthropol. Now 2020, 12, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Project: Intangible Heritage and Cultural Policies: Social, Political, and Museological Challenges. Funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and the FEDER Program, PGC2018-096190-B-I00. Available online: https://www.ub.edu/web/ub/es/recerca_innovacio/recerca_a_la_UB/projectes/fitxa/P/PJ014799/informacioGeneral/index.html (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Información. El Misteri Suspende las Representaciones de Agosto. 28 August 2020. Available online: https://www.informacion.es/elche/2020/04/28/misteri-suspende-representaciones-agosto-4676331.html (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Conde Nast. Así será la Fiesta de los Patios de Córdoba este octubre. 2020. Available online: https://www.traveler.es/experiencias/articulos/fiesta-patios-de-cordoba-octubre-2020-medidas-seguridad-covid/19260 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Ministerio de Cultura. Pautas para la Gestión, Conservación y Disfrute Público del Patrimonio Cultural en la Desescalada de la Crisis Sanitaria (covid-19). Available online: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/serviciosdeprensa/notasprensa/cultura/Documents/2020/010620-patrimonio_cultural.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- UNESCO. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/es/un-experiencia-de-patrimonio-vivo-y-la-pandemia-de-covid-19-01124?id=00061 (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Ajuntament de Vila-Real. Vila-Real Celebrará dos Nuevas Tamborradas en los Balcones. 2020. Available online: https://www.vila-real.es/portal/p_20_contenedor1.jsp?seccion=s_fnot_d4_v1.jsp&contenido=55929&tipo=8&nivel=1400&layout=p_20_contenedor1.jsp&codResi=1&language=es&codMenu=674 (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Las Provincias. La Gomera Lanza un Gran “Homenaje Silbado” a Aquellos que Luchan Contra el Covid-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.laprovincia.es/canarias/2020/05/21/gomera-lanza-gran-homenaje-silbado-8094133.html (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Expoflamenco. De los Tablaos y Academias a Internet. 2020. Available online: https://www.expoflamenco.com/actualidad/de-los-tablaos-y-academias-a-internet (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- De Flamenco. Home Flamenco, la Primera Peña Flamenco Online. 2 May 2020. Available online: https://www.deflamenco.com/revista/noticias/home-flamenco-la-primera-pena-flamenca-virtual.html (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Prometheus Museum. Available online: https://prometheus.museum/ (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Bindi, L. Fiestas Confinadas Comunidades Patrimoniales, Practicas Colectivas y Distanciamiento Social. In Patrimonio Inmaterial, Celebraciones Confinadas y Retos Post-COVID 19; Roigé, X., Canals, A., Eds.; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Ariño, A. Festa i ritual: Dos conceptes bàsics. Rev. Etnol. Catalunya 1997, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, R.J.; Marlovits, J. Life under lockdown: Notes on Covid-19 in Silicon Valley. Anthropol. Today 2020, 363, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Generalitat Valenciana. Acord de 19 de Juny, del Consell, Sobre Mesures de Prevenció Enfront de la Covid-19. 19 June 2020. Available online: http://dogv.gva.es/datos/2020/06/20/pdf/2020_4770.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Generalitat de Catalunya. Plans de Represa del Sector Cultural la Cultura Popular i les Associacions Culturals. 2021. Available online: http://interior.gencat.cat/web/.content/home/030_arees_dactuacio/proteccio_civil/consells_autoproteccio_emergencies/coronavirus/fases_confinament/plans-de-desconfinament-sectorials/Espectacles-culturals-llibreries-i-sales-dart/2020_07_17-DC-Pla-de-represa-de-la-cultura-popular-i-les-associacions-culturals.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Matheson, C.M. Festivity and sociability: A study of a Celtic music festival. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2005, 5, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, X. Festivity: Traditional and modern forms of sociability. Soc. Compass 2001, 48, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, L.S. Traditional Festivals. J. Festive Stud. 2013, 1, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozat, D.; Fournier, L.S. From Festivities to Leisure: Event, Merchandizing and the Creation of Places. Ann. Geogr. 2005, 3, 307–328. [Google Scholar]

- Vegheș, C. Cultural heritage, sustainable development and inclusive growth: Global lessons for the local communities under a marketing approach. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, A. Intertwining Processes of Reconfiguring Tradition: Three European Case Studies. Ethnol. Eur. 2020, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, A.P. El Carnaval de Negros y Blancos, patrimonio cultural del sur de Colombia en contexto de pandemia. Mediaciones 2020, 25, 109–204. [Google Scholar]

- Domene, J.F. La función social e ideológica de las fiestas religiosas: Identidad local, control social e instrumento de dominación. Dialectol. Tradic. Pop. 2017, 72, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronela, T. The importance of the intangible cultural heritage in the economy. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, D.; Robinson, M. Festivals, Tourism and Social Change: Remaking Worlds; Channel View Publications: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, T.; Gonzalez, F. International tourism and the UNESCO category of intangible cultural heritage. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Vanguardia. El Impacto Económico de Suspender las Fallas: 700 Millones de Euros. 2020. Available online: https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20200310/474084750556/valencia-aplaza-fallas-magdalena-coronavirus.html (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Centre de Prospectiva i Anàlisi dels Castells. 2020. Available online: https://www.cepac.cat/ (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Associació d’Estudis Fallers. Converses #FallasNau. 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Ml3KY0oCvw (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Fundació Horta Sud. Estudi de l’Avaluació de l’Impacte de les Associacions a l’Horta Sud. 2020. Available online: https://fundaciohortasud.org/descarregues/avaluacio-associacions.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Cejudo, R. Sobre el valor del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial: Una propuesta desde la ética del consumo. Dilemata 2014, 14, 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Castilla La Mancha. Plan de Medidas Extraordinarias para la Recuperación Económica de Castilla la Mancha con Motivo de la Crisis de la Covid-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.castillalamancha.es/sites/default/files/documentos/pdf/20200507/plan_medidas_extraordinarias_covid_19.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Guiaflama. La Confederación Andaluza de Peñas Flamencas Exije Medidas a las Administraciones ante el Covid-19. Available online: https://www.guiaflama.com/noticias/la-confederacion-andaluza-de-penas-flamencas-exige-medidas-a-las-administraciones-ante-el-covid-19/ (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Las Provincias. Las Fallas Precisan una Inyección de 3 Millones de Euros para Sobrevivir. 2021. Available online: https://www.lasprovincias.es/fallas-valencia/fallas-precisan-inyeccion-20210314211707-nt.html (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Ajuntament de València. 5 March 2021. Available online: https://www.valencia.es/-/nuevas-ayudas-sectores-económicos-vinculados-a-las-fallas (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Oral interview with a member of the organization of falles. Women of the town of Isil (Pallars Sobirà). The interview was conducting by the authors of the research (24 November 2020). Isil is a small town in the Catalan Pyrenees (only 77 inhabitants) where one of the most famous fire festivals in the Pyrenees is celebrated, visited by thousands of tourists. 24 November.

- Costa, X. Festive traditions in modernity: The public sphere of the festival of the ‘Fallas’ in Valencia (Spain). Sociol. Rev. 2002, 50, 482–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, V.; Rius, J.; Hernàndez, G. Ritual festivo, monopolio emocional y dominación social. Análisis del caso de las Fallas. Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Cuerpos Emoc. Soc. 2019, 31, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, I. Marketing turístico y fiestas locales: Estudio de caso de Las Fallas de Valencia. Cuad. Tur. 2020, 45, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mundo. El coronavirus tumba las fallas hasta que la situación lo permita. 2020. Available online: https://www.elmundo.es/comunidad-valenciana/2020/03/10/5e67aec021efa0bd618b45ee.html (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Valencia Plaza. Histórica Cremà Silencionsa. 2020. Available online: https://valenciaplaza.com/historica-crema-silenciosa-coronavirus-fallas-2020 (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Photo by Francesc Fort—Treball propi File licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. CoCC BY-SA 4.0. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=88012775 (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Generalitat de Catalunya. Resultats Electorals. Available online: https://resultats.parlament2021.cat/resultados/172/catalunya/barcelona/berga (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Noyes, D. Fire in the Placa: Catalan Festival Politics After Franco; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbo, A. La Patum de Berga: Festa, Guerra i Política; Diputació de Barcelona, Institut d’Estudis Catalans: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ara. Votar no a la Patum, un Sacrilegi Inimaginable fa Només uns Mesos. 2020. Available online: https://www.ara.cat/societat/berga-vota-suspendre-patum-coronavirus-covid-19_1_1132745.html (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Regió 7. Berga Oficialitza que no hi Haurà Patum per Corpus per Primer cop en 82 Anys. 2020. Available online: https://www.regio7.cat/bergueda/2020/05/25/lajuntament-berga-formalitza-ple-lascensio/613532.html (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Regió 7. L’Oposició en Ple Demana la Dimissió. 2020. Available online: https://www.regio7.cat/bergueda/2020/06/11/loposicio-berga-bloc-demana-dimissio/615956.html (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Festa en Directe. Les Associacions de Veïns de Berga Rebutgen els Salts Improvisats. 2020. Available online: https://www.festadirecte.cat/les-associacions-de-veins-de-berga-rebutgen-els-salts-improvisats-de-patum-perque-incompleixen-les-normes-sanitaries/ (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Ribot, A. Castells in the Construction of a Catalan Community: Body, Language, and Identity amidst Catalonia’s National Debate. Ph.D. Thesis, UC San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weig, D. Sardana and castellers: Moving bodies and cultural politics in Catalonia. Soc. Anthropol. 2015, 23, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentís, E.M. Por i perill: Vivències dels castellers. Rev. Etnol. Catalunya 1996, 9, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Betevé. El 74% dels Castellers Creuen que l’Aturada Perjudicarà les Colles. 2021. Available online: https://beteve.cat/cultura/enquesta-castellers-aturada-pandemia-coronavirus/ (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Douglas-Jones, R.; Hughes, J.J.; Jones, S.; Yarrow, T. Science, value and material decay in the conservation of historic environments. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 21, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, T. Popular Culture and the Turn to Gramsci. In Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: A Reader; Storey, J., Ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2006; pp. 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Olivera, A. Patrimonio inmaterial, recurso turístico y espíritu de los territorios. Cuad. Tur. 2011, 27, 663–677. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, T.L.G.; Trigo, J.P.; Gálvez, J.C.P.; Pesantez, S. El patrimonio inmaterial de la humanidad como herramienta de promoción de un destino turístico. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2017, 26, 568–584. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, M.D.; Gilman, L. UNESCO on the Ground: Local Perspectives on Intangible Cultural Heritage; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roigé, X.; del Mármol, C.; Guil, M. Los usos del patrimonio inmaterial en la promoción del turismo. El caso del Pirineo catalán. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2019, 17, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisset, L.K.; Noppen, L. Le patrimoine immatériel: Une arme à tranchants multiples. Téoros. Rev. Rech. Tour. 2005, 24, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, H. Las amenazas y riesgos del patrimonio mundial y del patrimonio cultural inmaterial. An. Mus. Nac. Antropol. 2012, 14, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tully, G. Are we living the future? Museums in the time of Covid-19. In Tourism Facing a Pandemic. From Crisis to Recovery; Burini, F., Ed.; Università degli Studi di Bergamo: Bergamo, Italy, 2020; pp. 229–242. [Google Scholar]

| A. ICH Elements (Year Incorporated and Type) | B. Description | C. Effects of COVID-19 | D. Digital Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Patum (2008) Berga (Catalonia) Beginning of June | Secular and religious theatrical performances, dances, pyrotechnics, and parades of mythical characters (monsters, fire devils) in the town square. | 2020/2021: Cancelled. Substituted by online activities. Protests and alternative celebrations, which gave rise to conflicts. | Patum in lockdown. Celebrations via social networks. Events on local television, children’s celebrations at home. |

| The Mystery Play of Elx (2008) Elx (Valencia) 14–15 August | Sacred sung musical drama about the death and assumption of the Virgin Mary. Performed since the fifteenth century in the local church and in the street. | 2020: Cancellation of performances. Shorter performances in religious services. | Online rehearsals. Online broadcasts. Online content uploaded. |

| Gomeran Whistling (2009) La Gomera (Canary Islands) | Whistling language used by island shepherds as a language for long-distance communication. The language is taught in schools. | 2020: Scarcely affected. Used as a means of communication between houses during lockdown. | Used and shared on social media. Whistled homages to healthcare workers. |

| Council of Wise Men on the Plain of Murcia Water Tribunal of the Plain of Valencia (2009) Weekly | Democratically elected tribunals for the administration of justice and resolution of conflicts amongst irrigation communities. | 2020: Cancellation of sessions during lockdown. | Website. |

| Castells (human towers) (2010) Catalonia Various festivities | Erection of human towers of different sizes and heights. Part of festivities in the cities and towns of Catalonia. The castells require the participation of many people. | 2020/2021: Complete cancellation of all events and rehearsals. Problems with training and continuity. Difficulties in restarting the activity due to restrictions. Loss of income | Alternative events via social media Training activities transmitted through social media. |

| Flamenco (2010) Andalusia and other regions | Mixture of song, dance, and instrumental accompaniment. Performed at celebrations or festivities. Distinctive feature of numerous groups and communities, especially the gypsy ethnic community. | 2020/201: Cancellation of performances and closure of tablaos, some permanently. Professional consequences for full-time artists. Loss of income | A 24 h online world event (Escuela de Flamenco de Andalucía). Platforms for online classes (Flamenco Culture, EFA Online and E-Dancer). Creation of online Flamenco clubs. |

| Chant of the Sybil (2010) Island of Mallorca Christmas Eve 24/25 of December | Song performed by two acolytes (boys or girls) in all the churches on Mallorca during the Christmas Eve Midnight Mass. | 2020: Various alternatives in different locations: (1) Limited places; (2) Change of time due to curfew; (3) Behind closed doors. | Some broadcasts on social media. Digital content. |

| Festival of the Mare de Déu de la Salut (2010) Algemesí (Valencia) 7/8 of September | Theatrical performances, concerts, and dances. Raising of human towers in the main square, with dances and music. | 2020: Cancelled. Religious services held. | Broadcast of events held in churches. |

| Fiesta of the patios (2012) Cordoba (Andalucía) May | Competition for most beautiful garden courtyards in dwellings inhabited by various families. | 2020: Change of dates. Celebration in autumn with limitations on visitor numbers. | Virtual 360° tour through different patios by means of an app. Individual videos of each patio via social networks. |

| Mediterranean Diet (2013) Cyprus, Croatia, Spain, Greece, Italy, and Portugal | Knowledge, practices, and rituals related to food and cooking in various Mediterranean communities. | 2020: Little impact, except for restaurant closures and group activities. Controversy: (1) Effects on dietary patterns; (2) Increased consumption of fruits and vegetables. | Exchange of recipes through social networks. Product promotion activities. |

| Summer solstice fire festivals in the Pyrenees (2015) Various villages in Andorra, Spain, and France 23/24 June | Villagers light torches in the mountains and bring them down to the town squares, where bonfires are lit and there is dancing and music. | 2020: Different alternatives among communities: (1) Cancellation of most events; (2) Change of date; (3) Some smaller events; (4) Limited to local people | Creation of the Prometheus Virtual Museum of Fire Festivals. Broadcasting of activities on social networks. Large amount of content on social networks. |

| Falconry (2016) Various countries | Birds of prey tamed for flight displays. | 2020: Difficulties in training birds of prey. Problems with stress in birds. | Virtual conference. |

| Valencia fallas (2016) Various towns and villages in the Valencia region 14–19 of March | Huge sculptures (fallas) composed of humorous figures burnt in streets and squares. | 2020: Cancelled. Some fallas were stored in warehouses. Subsequently, the fallas already set up in the street were burnt. 2021: Cancelled. Small-scale events | 2021. Virtual fallas. Virtual programs in most places. Participation in social networks. Virtual display of ninots (cardboard sculptures). Sharing of plantà dinner (beginning of the festivities) on social media. |

| Dry stone walling (2018) Croatia, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Spain, and Switzerland | Art of dry stone wall construction in houses and structures for agriculture and livestock. | 2020/21: Little impact. Cancellation of projects to train the next generation. Maintenance of various activities such as the Dry Stone Week in Catalonia. | Awareness-raising activities online. |

| Tamboradas drum playing ritutals (2018) Various municipalities in Andalusia, Aragon, Castile-La Mancha, Valencia, Murcia Easter Week | Prolonged and rhythmic ritual drumming by hundreds of drummers throughout the day and night. | 2020/2021: Cancellation and reduced format Drumming by children and adults on the balconies. | Digital content on social networks. Initiatives to record drumming on balconies. Virtual broadcasts. |

| Ceramic making (2018) Talavera de la Reina and Puente del Arzobispo (Castile La Mancha) | Communities of artisans who manufacture ceramic objects for domestic, decorative and architectural uses using traditional methods. | 2020/21: Economic impact of artisan store closures. Marketing difficulties. Aid plans to enable marketing of goods. | Online training activities. Promotion of online trade of ceramics. Creation of an online platform for sales. |

| Wine horses (2020) Caravaca de la Cruz (Murcia) 1–3 of May | Festival with parade of horses through the streets of the town with their handlers. | 2020: Cancelled | Program of virtual visits. |

| ICH Problems Caused by Pandemic | Challenges And Debates Over Post-COVID-19 Era | |

|---|---|---|

| Tourism | Lack of tourism | Doubts about recovery and dependence on tourism |

| Lack of economic resources | Tackling the overcrowding of some festivities | |

| Possible limits to tourism in some festivals | ||

| Cultural management of ICH | In associations: loss of members, reduction in sociability mechanisms In terms of economics: loss of income generated by activities, tourism, crafts, and public funding | In associations: recovery of partners, redefinition of role, organizational dynamics, lack of income In public policies: recovery plans. Regulation of practices in accordance with sustainable models and public health measures. Redefinition of practices |

| Local community and ICH values | Reinforcement of the role of ICH as a source of resilience and identity Prohibition of activities due to social distancing and the difficulty of controlling public capacity | Recovery of the community component in some overcrowded festivals More local Possible public distrust of large-scale events |

| Use of internet and social media | Intensive use of social networks, virtual spaces, and virtual museums New rituals and virtual events | Continuity of online practices The need for new communicative languages Role of museums and virtual inventories in the preservation of ICH |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roigé, X.; Arrieta-Urtizberea, I.; Seguí, J. The Sustainability of Intangible Heritage in the COVID-19 Era—Resilience, Reinvention, and Challenges in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115796

Roigé X, Arrieta-Urtizberea I, Seguí J. The Sustainability of Intangible Heritage in the COVID-19 Era—Resilience, Reinvention, and Challenges in Spain. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):5796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115796

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoigé, Xavier, Iñaki Arrieta-Urtizberea, and Joan Seguí. 2021. "The Sustainability of Intangible Heritage in the COVID-19 Era—Resilience, Reinvention, and Challenges in Spain" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 5796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115796

APA StyleRoigé, X., Arrieta-Urtizberea, I., & Seguí, J. (2021). The Sustainability of Intangible Heritage in the COVID-19 Era—Resilience, Reinvention, and Challenges in Spain. Sustainability, 13(11), 5796. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115796