Farmers’ Participation in Operational Groups to Foster Innovation in the Agricultural Sector: An Italian Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

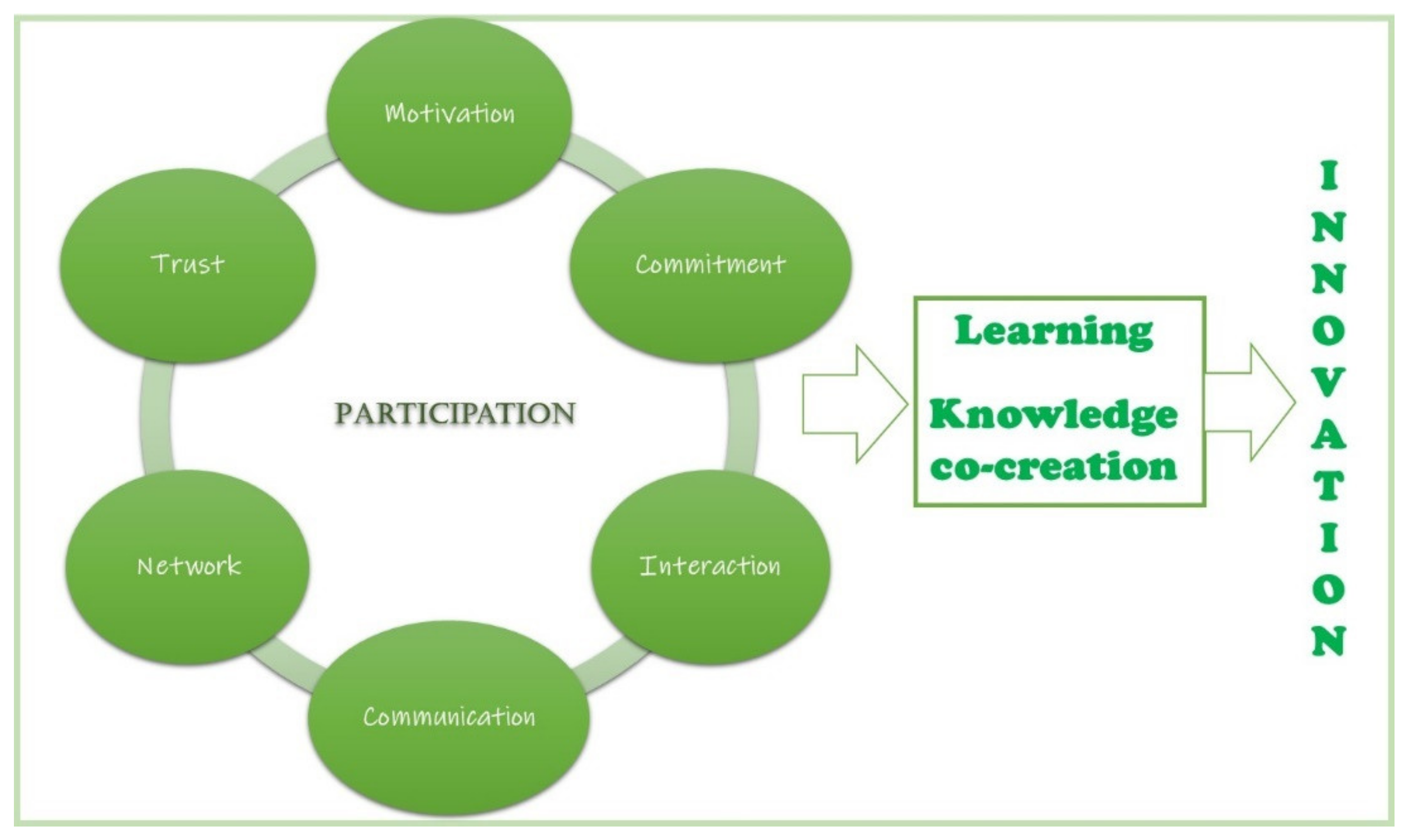

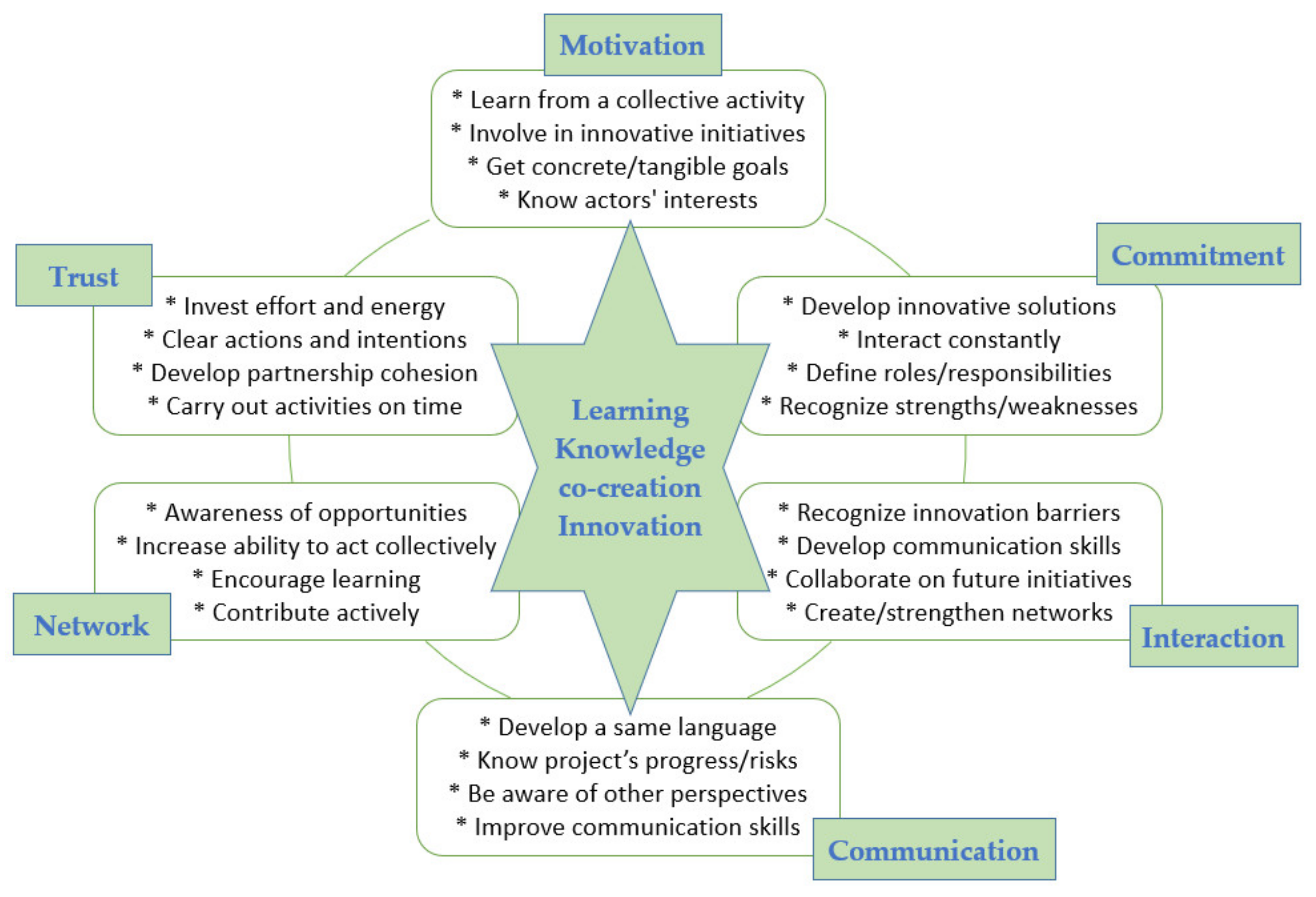

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Defining Participation

2.2. Factors That Influence the Participatory Innovation Process

2.2.1. Motivation

2.2.2. Commitment

2.2.3. Interaction

2.2.4. Communication

2.2.5. Networks

2.2.6. Trust

2.3. Outcomes of Participatory Innovation Processes

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Farmers Lab Background

4.2. Factors That Influence the Participatory Innovation Process

4.2.1. Motivation

4.2.2. Commitment

4.2.3. Interaction

4.2.4. Communication

4.2.5. Networks

4.2.6. Trust

4.3. Outcomes of Participatory Innovation Processes

5. Discussion

5.1. Motivation

5.2. Commitment

5.3. Interaction

5.4. Communication

5.5. Networks

5.6. Trust

5.7. Learning and Knowledge Co-Creation

5.8. Innovation

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- How are relations with the funding body (Region and AVEPA)?Who maintains the formal relationships?How are the doubts or problems addressed between the funding body and the project?

- Did the funding agency have any other roles besides project selection and funding disbursement? Which?Was support provided by the region? Of what type?

- 3.

- Analyzing the partnership, why were these partners chosen? In retrospect, there would have been a need to include other partners: who and why?

- 4.

- What are the characteristics of the different actors and their role in the co-creation project?

- 5.

- What type of organization and decision-making process has been adopted by the partnership?Are there formal contracts/agreements among the partners in your project?Are there formal rules or regulations governing relationships?

- 6.

- How are the relationships between the partners?How is the communication between the different partners in your project?Do you share a common language?What happens if there is disagreement or conflict? How do you find a solution?How do you cooperate with each other?

- 7.

- How has the innovation process outlined in the project evolved over time?How and when were the partnership goals established?

- 8.

- What are your goals and motivations for participating in the project?What is in the project for you? To which extent are they fulfilled?

- 9.

- How are the decision-making processes within the project? What do the different partners think?Describe the organizational and decision-making process (procedures, meetings, whether one actor is in charge)Who are the key decision-makers and why?Personally, do you think you have an influence on the partnership, why?Is your opinion considered when decisions are made? In what way?Do you have an influence on what is happening in the partnership? (why not?)

- 10.

- The different actors, what kind of knowledge did they bring? Was it relevant? How was it shared?How did the different actors learn from each other (with what tools and methods)?What worked and what did not work in the interaction between the different actors?

- 11.

- How and when were the project goals set? How were they kept up to date?Process toward setting them?Who was involved or excluded?

- 12.

- How do you feel in terms of being considered and heard? ExampleWould you collaborate with these partners again? Why?Were your opinions, knowledge, or skills considered?Did the interaction between the partners go smoothly or somewhat difficult? Why?

- 13.

- What are the three success factors of the partnership (regarding interaction within the partnership) and what are the three most difficult factors?

- 14.

- How is communication with stakeholders organized?To what extent (and how) are they involved in the project?Has their opinion/ involvement affected the project?What is their role?

- 15.

- Were there sufficient opportunities to interact with stakeholders and vice versa? Why (not)?How and how often were communications/relationships developed?

- 16.

- Why were stakeholders involved in the project case?

- 17.

- Do you believe that the overall context in which you operate is capable of supporting interactive innovation initiatives?Who were the stakeholders you interacted with and why?What kind of support did you receive or would you have liked to receive from external actors?What obstacles did you encounter?

- 18.

- Do you feel that your experience has had or is likely to have any effects on the context? Which ones?What is your next step?

- 19.

- What is the relationship with other Operational Groups?

- 20.

- Have there been opportunities to connect with other multi-actor innovation projects? Why (not)?Are there any official networking events relevant to your project?Have you participated in any events? Why (not)?In your opinion, who should organize or provide these types of opportunities?What do you think are the benefits of linking or networking with other innovation projects?Who participates in these meetings?

Appendix B

| Actor | Motivation | Communication | Interaction | Commitment | Trust |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer 1 | Increase farms profitability Decrease food waste Relate with actors from different backgrounds Increase participation Show that a future in agriculture is worthy | Know new ways of organizing, cooperating, and learning | Idea’s interchange with professionals outside the agricultural world Recognize equality among actors | Leave farms to attend to meetings Be part of a new and stimulating experience Provide information and inputs Give direction for innovations Reach the set objectives | Each partner carried out their activities Partners available to listen what was happening in each area Clear rules and pathway to follow |

| Farmer 2 | Achieve something different and recognizable | Difficult to understand each other- not a common language Technical terms were hard to understand Use of simple words | Work together also for future opportunities Farmers were not always constant | Contribute to build a culture of innovation | Responsibilities and roles were clear since the beginning of the initiative |

| Farmer 3 | Share experiences Offer a quality product Put aside individualistic behavior Work on a project with a common goal | Define and understand activities to be developed | Compare different realities Cross information Identify existing opportunities | Succeed in a bottom-up initiative Discover agriculture potential Share ideas to put them into practice | Time developed esteem and friendship Responsibilities were Shared Knowledge, experience and professionalism Good leadership |

| Farmers 4 | Succeed in bottom-up initiative Know more about product processing Preserve farms in the territory Cooperate with others to respond to a need | Be open minded, focus on finding the solution, share what the limits are, and propose ways to address possible inconvenient | Difficult to set up timetables for everyone (meetings) | Keep motivation up Understand the activities to be developed | Example that a non-collaborative context can change Skilled partners contribute for the development of an innovative context |

| Stakeholder | Know and compare diverse perspectives | Discover opportunities | Connect the education system with practice | Work in what is needed without complication Reach agreements Move from words to action | Every partner had their own space Cooperate between different actors and get positive results |

| Innovation Broker | Provide expertise to the project Build a network Replicate the initiative around the territory | Use of technical words with caution Use terms closer to everyday life | Look for a solution for a specific topic Resolve partnership issues as a group No continuous interaction with other OGs (all were focused on their own businesses) | Dedicate time and energy around a common goal | Each partner had an assigned task Partners listen to the group reactions Inclusive decision making process Flexibility in the activities to be performed |

| Researcher | Contribute to the agri-food sector | Use common and simple words Learn to speak the same language Farmer’s availability to attend to the project meetings was prioritized | Spaces to interact: meetings, teleconference, skype, OG website, social networks, e-mails, cell phone messages and calls | Contribute with previous experience | Not conflicts within the partnership Lean relationship among partners Specific objectives for each actor |

| Trader | Liaise and work with different partners Make known small shops | Know the reality of the field | Define how to carry out the planned activities Merge different perspectives | Comply with the proposed schedule Do not get lost along the way | Time was needed to gain some confidence Disposition of partners towards the group Excellent coordination Partners’ skills aligned with the project needs |

| Actor | Network | Knowledge Co-Creation | Learning | Innovation | |

| Farmer 1 | Dissemination activities Find out who has succeeded, their results, what worked and what did not | Financial reporting was a critical aspect | Meetings where the space to discuss and learn | Work together in a region where it is not normally done in that way Create a link between stakeholders who previously did not speak to each other or had difficulties in doing so | |

| Farmer 2 | Involvement with other actors Build a climate of cooperation | Common language based on achieving the project’s goals Involvement of agricultural enterprises and consumers | Written reports promoted the need for a space to exchange, intervene, discuss, and ask questions and clarifications | Farmers’ interventions were considered for improving their realities | |

| Farmer 3 | Build the capacity of innovation actors | Periodically progress dissemination among the partners (e-mails, written reports, SMS) | Not taking anything for granted Each one has a different method and way of doing things Observing others | New practices of marketing | |

| Farmer 4 | No time to expand the network | Farmers were the main actor Clue: avoid ruling over each other | Extend knowledge on how to transform products | Interact with other partners and be aware of their farms improvements | |

| Stakeholder | New opportunities | Physical meetings and open discussions Positive attitude, open mind, and motivation to cooperate | Partnership discussions Space to learn from different partners | Way of working new to the context in which it developed | |

| Innovation Broker | Start looking at each other and get involved to cooperate | Share ideas, dialogue, make adjustments Topics or ideas to be discussed could be anticipated by an e-mail Each partner spoke for his/her own competence | Peer to peer learning | Put together actors with different skills to design collectively | |

| Researcher | Know other groups activities and implementation process | Decisions related to the contents, management, and coordination of the project Democratic discussions (no restrictions or discrimination) | Communication skills to understand the needs of producers and consumers Knowledge expansion about topics out of their fields of expertise | Inform producers about the packaging technology for their products | |

| Trader | Share skills and knowledge | Disposition, cooperation, collaborative attitude, motivation, and empathy among participants Understanding of what each partner completed or wanted to accomplish | Circulation of information among the partners Involvement (opinions and remarks) on the developed activities Actors well prepared in their fields | ||

References

- European Commission (European Commission, Brussels, Belgium). A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environ-Mentally Friendly Food System, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; EU: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oerlemans, N.; Assouline, G. Enhancing farmers’ networking strategies for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2004, 12, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, J.; White, T.; Blackett, P.; Rijswijk, K.; Bewsell, D.; Park, N.; Turner, J.A.; Botha, N. Evaluating a space for co-innovation: Practical application of nine principles for co-innovation in five innovation projects. Outlook Agric. 2017, 46, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinska, A.; D’Aquino, P. Farmers as agents in innovation systems. Empowering farmers for innovation through communi-ties of practice. Agric. Syst. 2016, 142, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, N.; Turner, J.A.; Fielke, S.; Klerkx, L. Using a co-innovation approach to support innovation and learning: Cross-cutting observations from different settings and emergent issues. Outlook Agric. 2017, 46, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylova, A.A. The evolution of the innovation process modeling. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. 2014, 2, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Klerkx, L.; van Mierlo, B.; Leeuwis, C. Evolution of systems approaches to agricultural innovation: Concepts, analysis and interventions. In Farming Systems Research into the 21st Century: The New Dynamic, 1st ed.; Darnhofer, I., Gibbon, D., Dedieu, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 457–483. [Google Scholar]

- Knickel, K.; Brunori, G.; Rand, S.; Proost, J. Towards a Better Conceptual Framework for Innovation Processes in Agriculture and Rural Development: From Linear Models to Systemic Approaches. In Proceedings of the 8th European IFSA Symposium, Clermont-Ferrand, France, 6–10 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ville, A.S.S.; Hickey, G.M.; Phillip, L.E. How do stakeholder interactions influence national food security policy in the Caribbean? The case of Saint Lucia. Food Policy 2017, 68, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Innovation System Capacity: A Comparative Analysis of Case Studies. In Enhancing Agricultural Innovation: How to go Beyond the Strengthening of Research Systems, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, L.; Buller, H.; Cronien, E.; Slavova, P. Better Rural Innovation: Linking Actors, Instruments and Policies through Networks; Short Version of MS1: Draft Conceptual Framework; LIAISON: Horizon 2020 Grant Agreement No. 773418. 2019. Available online: https://liaison2020.eu/conceptual-framework/ (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Schut, M.; Andersson, J.A.; Dror, I.; Kamanda, J.; Sartas, M.; Mur, R.; Kassam, S.N.; Brouwer, H.; Stoian, D.; Devaux, A.; et al. Guidelines for Innovation Platforms in Agricultural Research for Development: Decision Support for Research, Development and Funding Agencies on How to Design, Budget and Implement Impactful Innovation Platforms; Under the CGIAR Research Program on Roots Tubers and Bananas (RTB); International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA): Ibadan, Nigeria; Wageningen University (WUR): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Détang-Dessendre, C.; Geerling-Eiff, F.; Guyomard, H.; Poppe, K. EU Agriculture and Innovation: What Role for the Cap? INRA: Paris, France; WUR: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- The European Innovation Partnership (EIP) for Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability. Managing Multi-Actor projects and processes. In Interactive Innovation in Action—Multi-Actor Projects Learning from Each Other, Cross-Fertilisation Event for Multi-Actor Projects, Brussels, Belgium, 8 March 2018; EU Commission DG Agriculture and Rural Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brunori, G.; Barjolle, D.; Dockes, A.; Helmle, S.; Ingram, J.; Klerkx, L.; Moschitz, H.; Nemes, G.; Tisenkopfs, T. CAP Reform and Innovation: The Role of Learning and Innovation Networks. EuroChoices 2013, 12, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIP-AGRI Service Point Innovation Support Services. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/eip (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Vik, J.; Stræte, E.P. Embedded Competence: A Study of Farmers’ Relation to Competence and Knowledge. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2017, 392–403. [Google Scholar]

- Dolinska, A. Bringing farmers into the game. Strengthening farmers’ role in the innovation process through a simulation game, a case from Tunisia. Agric. Syst. 2017, 157, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytelka, L.K. Local systems of Innovation in a Globalized World Economy. Ind. Innov. 2000, 7, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Berti, G.; Klerkx, L.; Roep, D.; Tisenkopfs, T.; Moschitz, H.; Home, R.; Barjolle, D.; Curry, N. Learning and Innovation Networks for Sustainable Agriculture: A Conceptual Framework. Report for SOLINSA Project; FP7, Grant Agreement 266306. 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239848607 (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Sumane, S.; Kunda, I.; Knickel, K.; Strauss, A.; Tisenkopfs, T. Local and farmers’ knowledge matters! How integrating informal and formal knowledge enhances sustainable and resilient agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakku, E.; Thorburn, P.J. A conceptual framework for guiding the participatory development of agricultural decision support systems. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tödtling, F.; Trippl, M. One size fits All? Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fieldsend, A.F.; Cronin, E.; Varga, E.; Biró, S.; Rogge, E. ‘Sharing the space’ in the agricultural knowledge and innovation system: Multi-actor innovation partnerships with farmers and foresters in Europe. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederen, P.; Van Meijl, H.; Wolters, A. Modernisation in agriculture: What makes a farmer adopt an innovation? In Proceedings of the Xth EAAE Congress ‘Exploring Diversity in the European Agri-Food System’, Zaragoza, Spain, 28–31 August 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kumba, F. Farmer Participation in Agricultural Research and Extension Service in Namibia. J. Int. Agric. Ext. Educ. 2003, 10, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Network for Rural Development (ENRD, Brussels, Belgium). Rural Development Programme: Key Facts & Figures Italy-Veneto. 2015. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Veneto Region (Veneto Region, Venezia, Italy). Italy—Rural Development Programme (Regional)—Veneto. 2019. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/country/italy_en (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Piergiovanni, R. Gibrat’s Law in the “Third Italy”: Firm Growth in the Veneto Region. Growth Chang. 2010, 41, 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemessa, S.D.; Yismaw, M.A.; Watabaji, M.D. Risk induced farmers’ participation inagricultural innovations: Evidence from a field experiment in eastern Ethiopia. Dev. Stud. Res. 2019, 6, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macken-Walsh, A. Partnership and subsidiarity? A case-study of farmers’ participation in contemporary EU governance and rural development initiatives. Rural Soc. 2011, 21, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaunga, S.; Mudhara, M. Determinants of farmers’ participation in collective maintenance of irrigation infrastructure in KwaZulu-Natal. Phys. Chem. Earth 2018, 105, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommen, N.O.; Blut, M.; Backhaus, C.; Woisetschläger, D.M. Toward a better understanding of stakeholder participation in the service innovation process: More than one path to success. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2409–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, R.; Toogood, M.; Knierim, A. Factors Affecting European Farmers’ Participation in Biodiversity Policies. Sociol. Rural. 2006, 46, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, P.; Ryan, M.; O’Donoghue, C.; Hynes, S.; Huallacháin, D.Ó.; Sheridan, H. Impact of farmer self-identity and attitudes on participation in agri-environment schemes. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastra-Bravo, X.B.; Hubbard, C.; Garrod, G.; Tolón-Becerra, A. What drives farmers’ participation in EU agri-environmental schemes? Results from a qualitative meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldberg, K.; Mackness, J. Foundations of communities of practice: Enablers and barriers to participation. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2009, 25, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities ofpractice: Learning asa social system. Syst. Think. 1998, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, K. Farm-level constraints on agri-environmental scheme participation: A transactional perspective. J. Rural. Stud. 2000, 16, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Maturano, J.; Speelman, S.; De Steur, H. Constraint-based innovations in agriculture and sustainable development: A scoping review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofré-Bravo, G.; Klerkx, L.; Engler, A. Combinations of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital for farm innovation: How farmers configure different support networks. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, M.A. The Evaluation of Regional Innovation and Cluster Policies: Towards a Participatory Approach. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaans, K.; Cullen, B.; van Rooyen, A.; Adekunle, A.; Ngwenya, H.; Lema, Z.; Nederlof, S. Dealing with critical challenges in African innovation platforms: Lessons for facilitation. Knowl. Manag. Dev. J. 2013, 9, 116–135. [Google Scholar]

- Boogaard, B.; Dror, I.; Adekunle, A.A.; Le Borgne, E.; van Rooyen, A.; Lundy, M. Developing Innovation Capacity through Innovation Platforms; Innovation Platforms Practice Brief 8; International Livestock Research Institute: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen, P.M.; Hoeve, A.; Nieuwenhuis, L.F. Learning Entrepreneurs: Learning and Innovation in Small Companies. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 2, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, B.; Lambrecht, E.; Vanhonacker, F.; Pieniak, Z.; Gellynck, X. Factors Underlying Farmers’ Decisions to Participate inNetworks. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2013, 4, 198–213. [Google Scholar]

- Swaans, K.; Boogaard, B.; Bendapudi, R.; Taye, H.; Hendrickx, S.; Klerkx, L. Operationalizing inclusive innovation: Lessons from innovation platforms in livestock value chains in India and Mozambique. Innov. Dev. 2014, 4, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breetz, H.L.; Fisher-Vanden, K.; Jacobs, H.; Schary, C. Trust and communication: Mechanisms for increasing farmers’ partic-ipation in water quality trading. Land Econ. 2005, 81, 170–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.; Falk, T.; Siegmund-Schultze, M.; Spangenberg, J.H. The Objectives of Stakeholder Involvement in Transdiscipli-nary Research. A Conceptual Framework for a Reflective and Reflexive Practise. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 176, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiper, C.; Clarke-Sather, A. Co-creating an alternative: The moral economy of participating in farmers’ markets. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 840–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalani, B.; Dorward, P.; Holloway, G.; Wauters, E. Smallholder farmers’ motivations for using Conservation Agriculture and the roles of yield, labour and soil fertility in decision making. Agric. Syst. 2016, 146, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, R.; Patterson, L.; Miller, O. Motivations, risk perceptions and adoption of conservation practices by farmers. Agric. Syst. 2009, 99, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson-Ngwenya, P.; Restrepo, M.J.; Fernández, R.; Kaufmann, B.A. Participatory video proposals: A tool for empowering farmer groups in rural innovation processes? J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, J.; Beers, P.J.; Wals, A.E. Social learning in regional innovation networks: Trust, commitment and reframing as emergent properties of interaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 49, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Fielke, S.; Bayne, K.; Klerkx, L.; Nettle, R. Navigating shades of social capital and trust to leverage opportunities for rural innovation. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, P.J.; Sol, J.; Wals, A. Social learning in a multi-actor innovation context. In Proceedings of the 9th European IFSA Symposium, Vienna, Austria, 4–7 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klerkx, L.; Aarts, N. The interaction of multiple champions in orchestrating innovation networks: Conflicts and complementarities. Technovation 2013, 33, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Garguilo, M. Where do networks come from? Am. J. Sociol. 1999, 10, 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tödtling, F.; Lehner, P.; Kaufmann, A. Do different types of innovation rely on specific kinds of knowledge interactions? Technovation 2009, 29, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, O.M.; Poortvliet, P.M.; Klerkx, L. To cluster or not to cluster farmers? Influences on network interactions, risk perceptions, and adoption of aquaculture practices. Agric. Syst. 2019, 173, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigford, A.A.; Hickey, G.M.; Klerkx, L. Beyond agricultural innovation systems? Exploring an agricultural innovation ecosystems approach for niche design and development in sustainability transitions. Agric. Syst. 2018, 164, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, W.L.; Furman, C.; Diehl, D.; Royce, F.; Dourte, D.; Ortiz, B.; Zierden, D.; Irani, T.; Fraisse, C.; Jones, J. Warming up to climate change: A participatory approach to engaging with agricultural stakeholders in the Southeast US. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013, 13, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalsveen, K.; Ingram, J.; Urquhart, J. The role of farmers’ social networks in the implementation of no-till farming practices. Agric. Syst. 2020, 181, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Rossi, A.; Malandrin, V. Co-producing transition: Innovation processes in farms adhering to Solidarity-based Purchase Groups (GAS) in Tuscany, Italy. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2010, 18, 28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and Mode 2 to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepic, M.; Trienekens, J.H.; Hoste, R.; Omtad, S.W. The influence of networking and absorptive capacity on the innovativeness of farmers in the dutch pork sector? Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Assoc. 2012, 15, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Douthwaite, B.; Mur, R.; Audouin, S.; Wopereis, M.; Hellin, J.; Moussa, A.; Karbo, N.; Kasten, W.; Bouyer, J. Agricultural Research for Development to Intervene Effectively in Complex Systems and the Implications for Research Organizations; Royal Tropical Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Savaget, P.; Geissdoerfer, M.; Kharrazi, A.; Evans, S. The theoretical foundations of sociotechnical systems change for sustainability: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 878–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, L.; Buller, H.; Blokhuis, H.; van Niekerk, T.; Voslarova, E.; Manteca, X.; Weeks, C.; Main, D. HENNOVATION: Learnings from promoting practice-led multi-actor innovation networks to address complex animal welfare challenges within the laying hen industry. Animals 2019, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klerkx, L.; Aarts, N.; Leeuwis, C. Adaptive management in agricultural innovation systems: The interactions between innovation networks and their environment. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, C.; Briggeman, B.C. Farmers’ perceptions of building trust. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Assoc. 2016, 19, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezezika, O.C.; Oh, J. What is trust? Perspectives from farmers and other experts in the field of agriculture in Africa. Agric. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Kemp, R.; Haxeltine, A. Game-changers and transformative social innovation. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, G.P.; Verganti, R. Which kind of collaboration is right for you? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 86, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, F.; Stuiver, M.; Beers, P.J.; Kok, K. The distribution of roles and functions for upscaling and outscaling innovations in agricultural innovation systems. Agric. Syst. 2013, 115, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Mason-Jones, R. Communities of interest as a lens to explore the advantage of collaborative behaviour for developing economies: An example of the Welsh organic food sector. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2017, 18, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tödtling, F.; Kaufmann, A. Innovation systems in regions of Europe-a comparative perspective. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2007, 7, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Perraton, J.; Tarrant, I. What does tacit knowledge actually explain? J. Econ. Methodol. 2007, 14, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodorkós, B.; Pataki, G. Linking academic and local knowledge: Community-based research and service learning for sustainable rural development in Hungary. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Ledermann, T.; Rist, S.; Fry, P. Social learning processes in Swiss soil protection—The ‘From Farmer—To Farmer’ project. Hum. Ecol. 2009, 37, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilli, M.D.; Aranguren, M.J.; Larrea, M. The role of interactive learning to close the ‘innovation gap’ in SME-based local economies: A furniture cluster in the basque country and its key policy implications. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, T. Social (un-)learning and the legitimization of marginalized knowledge: How a new community of practice tries to ‘kick the grain habit’ in ruminant livestock farming. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Reinmoeller, P.; Senoo, D. The ‘ART’ of knowledge: Systems to capitalize on market knowledge. Eur. Manag. J. 1998, 16, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.; Pascucci, S. Mapping the organisational forms of networks of alter- native food networks: Implications for transition. Sociol. Rural 2017, 57, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, D.J.; Birner, R. How Innovative is Your Agriculture? Using Innovation Indicators and Benchmarks to Strengthen National Agricultural Innovation Systems; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chamber of Commerce of Padua. Available online: http://opendata.unioncamereveneto.it/ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

| Respondent | Sector | Previous Participation Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Farmer (coordinator) | Agriculture | No |

| Farmer | Agriculture | No |

| Farmer | Agriculture | No |

| Farmer | Agriculture | No |

| Researcher | Design & Engineering | Yes |

| Trader | Commerce, tourism, services | Yes |

| Innovation Broker | Manufacturing, industry 4.0, agri-food | Yes |

| External Stakeholder | Education | Yes |

| Project Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Pioneer farmers | Coordinator |

| Researchers | Food design brand and packing prototype |

| Researchers | Products’ sensory analysis |

| Vocational training institution | Analyze and segment farms by product type |

| Innovation support | Innovation broker |

| Non-Governmental Organization | Designer |

| SME’s association | Trader |

| Actors/Factors | Farmers | Stakeholder | Innovation Broker | Researcher | Trader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | Increasing farms’ profitability Adding value to fruits & vegs No food waste | Knowing and compare diverse perspectives | Replicating the initiative around the territory | Contributing to the agri-food sector | Liaising and working with different partners |

| Commitment | Leaving farms to attend to meetings Provide info/inputs | Learning of what happens in other areas | Dedicating time and energy around a common goal | Contributing with previous experience | Succeeding in a bottom-up initiative |

| Interaction | Interchanging ideas with professionals outside agriculture | Listening each ones’ arguments | Resolving issues as a group Keeping balance between formal and informal relations Identifying needs, interests, competencies | Interacting in meetings, teleconference, skype, OG website, social networks, e-mails, SMS, and calls | Sharing ideas to define how to carry out activities Merging different perspectives Sharing: no restrictions/discrimination |

| Communication | Building a shared language Focusing on finding solutions, and share the limits | Discovering opportunities Ongoing discussions | Using terms closer to everyday life | Resolving issues as a team- productive dialogue | Making use of spaces for coordination (physical and virtual) |

| Network | Finding out who has succeeded, their results, what worked and what did not | Gathering information | Knowing other groups’ activities and implementation process Interacting with other OGs | Disseminating activities | |

| Trust | Clear responsibilities and roles Skill partners contributions | Partners have their own space Cooperation between different actors | Each partner had an assigned task Inclusive decision-making process | No doubts on what to do and when No internal conflicts Specific objectives for each actor | Time needed Partners’ disposition towards the group Partners’ skills aligned with project needs |

| Learning | Meetings: active discussions | Partnership discussions Space to learn from different partners | Open and democratic conversations Jointly reflect on what could be improved | Knowledge expansion about unknown topics | Information circulation Activities’ involvement |

| Knowledge co-creation | Periodically dissemination progress among partners | Physical meetings and open discussions Positive attitude and willingness to cooperate | Written reports promoted the need for a space to exchange, discuss, and clarify | Democratic discussions Through available multimedia tools | Awareness of what each partner completed or wanted to accomplish |

| Innovation | Teamwork where it is not common New links between stakeholders | New way of working | Synergy among actors with different skills to design collectively | New packaging tech for agricultural products |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina, N.; Brunori, G.; Favilli, E.; Grando, S.; Proietti, P. Farmers’ Participation in Operational Groups to Foster Innovation in the Agricultural Sector: An Italian Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105605

Molina N, Brunori G, Favilli E, Grando S, Proietti P. Farmers’ Participation in Operational Groups to Foster Innovation in the Agricultural Sector: An Italian Case Study. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105605

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina, Natalia, Gianluca Brunori, Elena Favilli, Stefano Grando, and Patrizia Proietti. 2021. "Farmers’ Participation in Operational Groups to Foster Innovation in the Agricultural Sector: An Italian Case Study" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105605

APA StyleMolina, N., Brunori, G., Favilli, E., Grando, S., & Proietti, P. (2021). Farmers’ Participation in Operational Groups to Foster Innovation in the Agricultural Sector: An Italian Case Study. Sustainability, 13(10), 5605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105605