Sustainable Shift from Centralized to Participatory Higher Education in Post-Soviet Countries: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

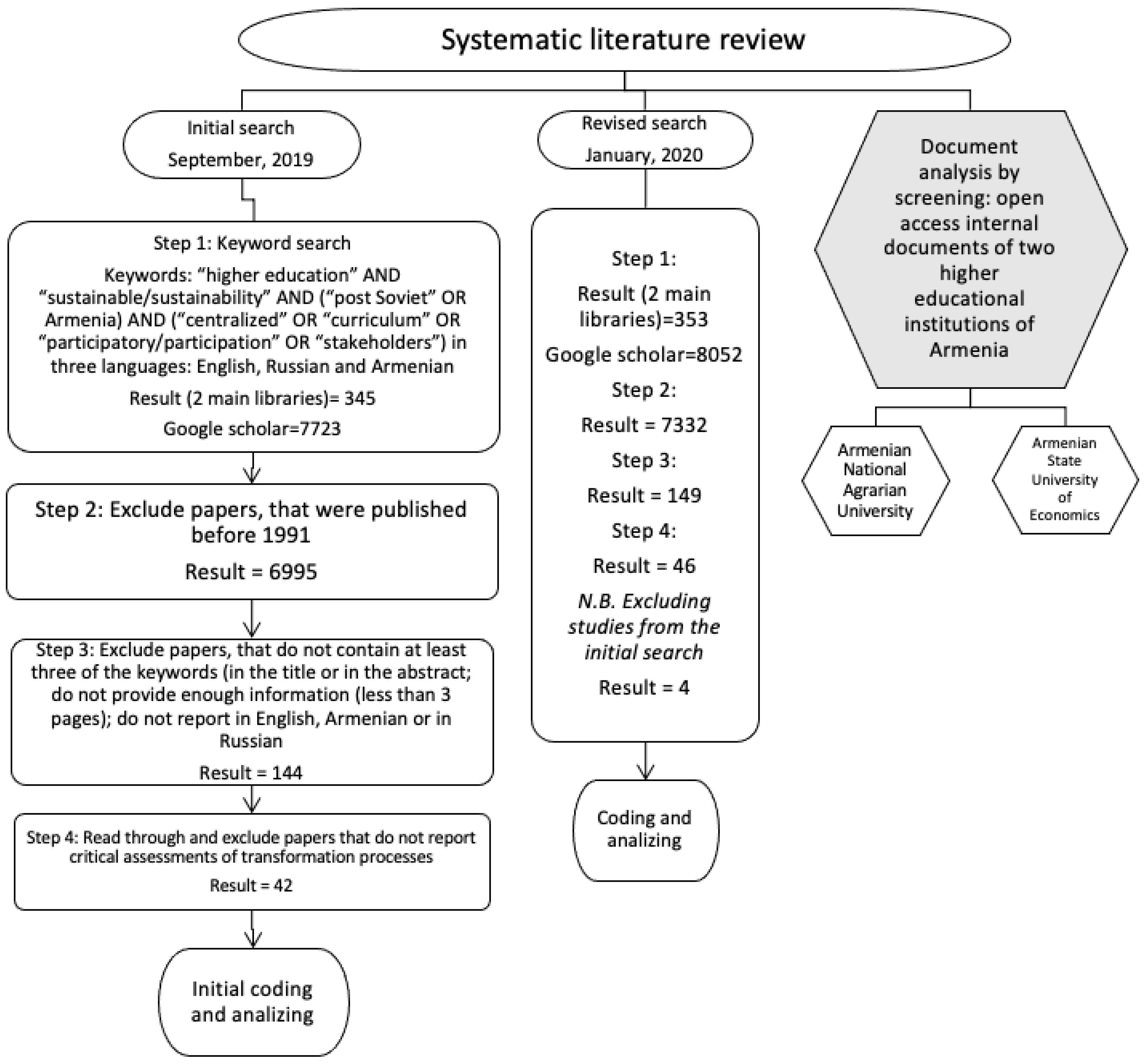

2. Methods

2.1. Initial Search (September 2019)

2.2. Revised Search (January 2020)

2.3. Document Analysis

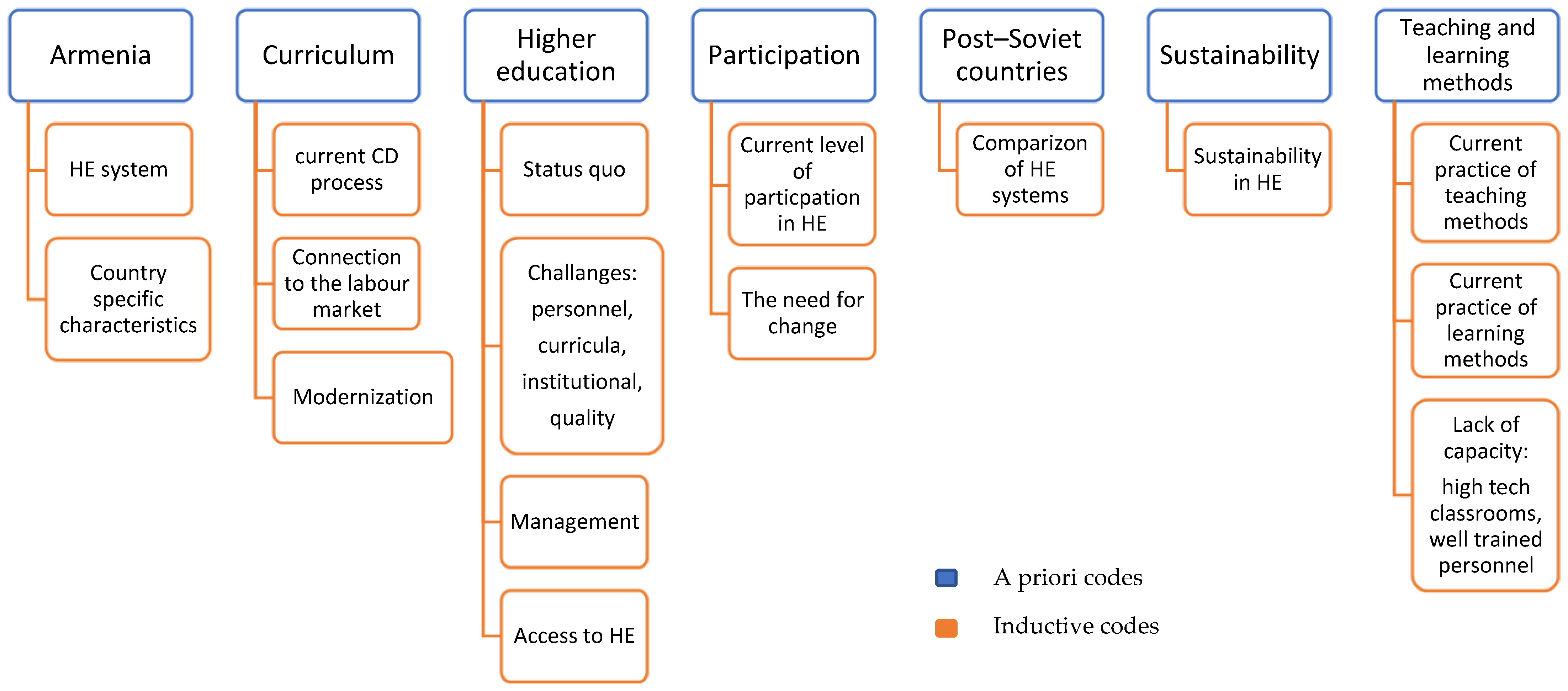

2.4. Detailed Review of Each Study

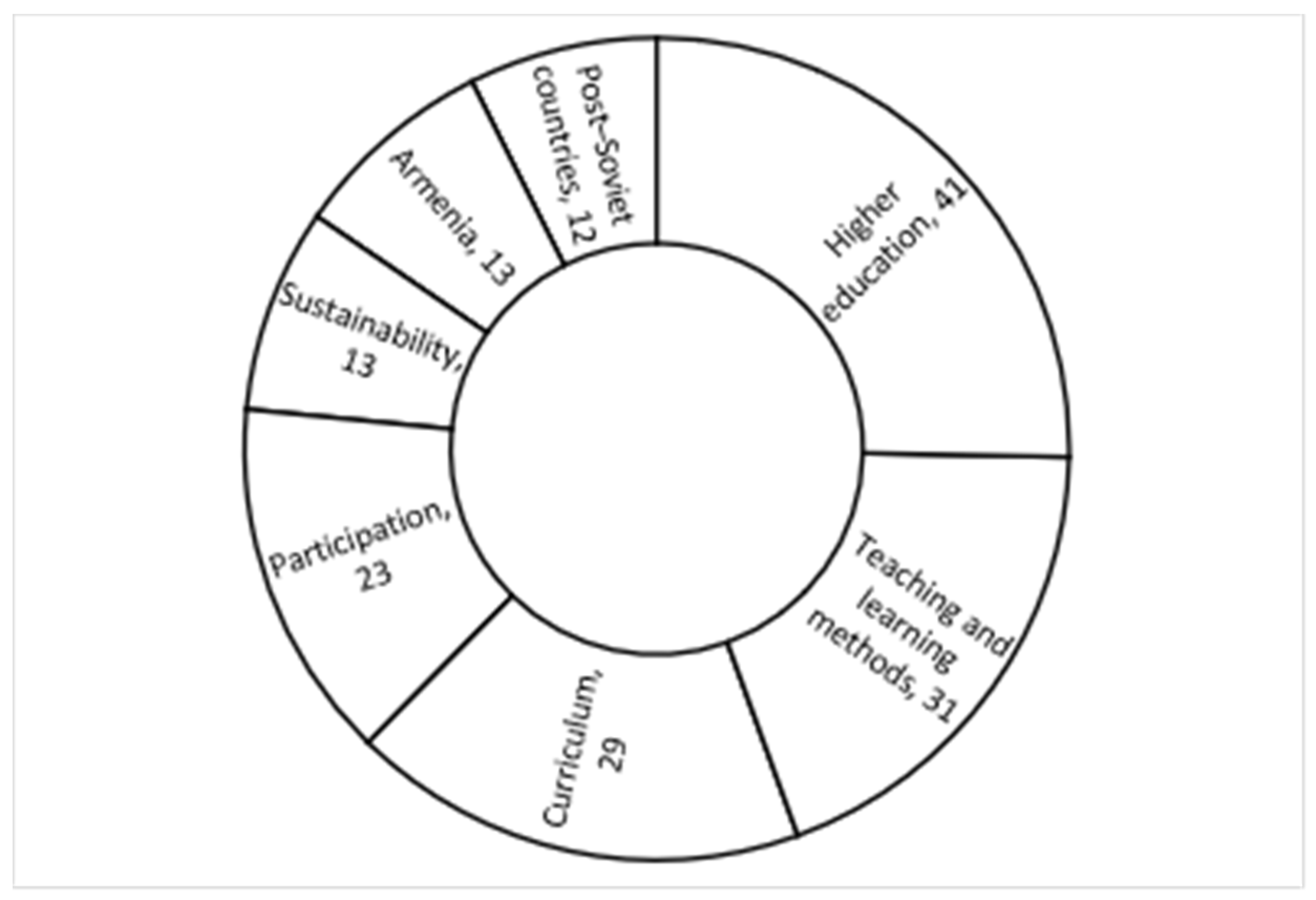

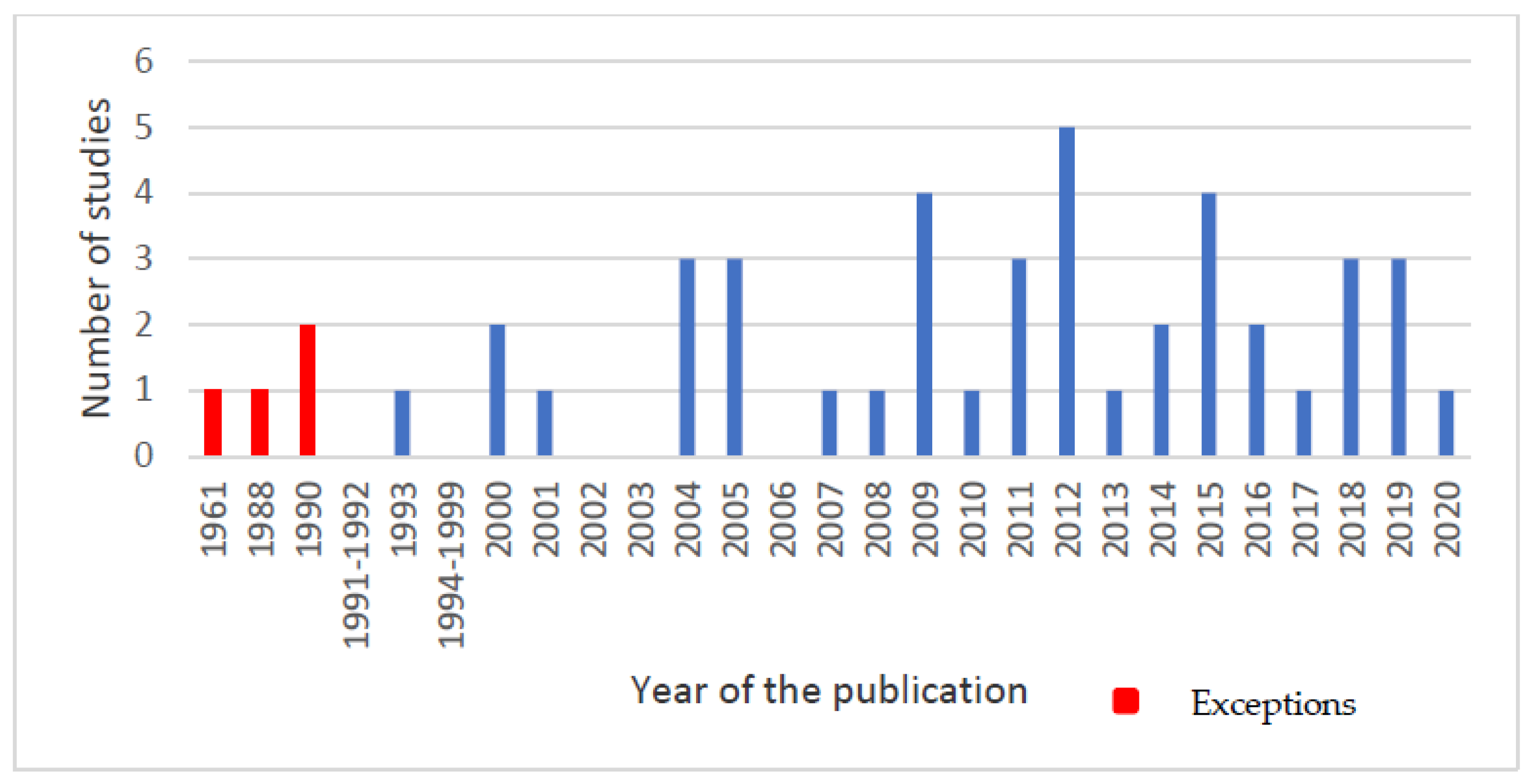

3. Results

3.1. Performance Analysis

3.2. Background and Status Quo of the Current Higher Education System in Armenia

3.3. Challenges of Higher Education in Armenia

3.4. The Need for Transformation

- Motivation of students, as they feel responsible for their own learning programs;

- Teaching material is more relevant, as it reflects the learning needs of the students;

- The learning process is more permanent, as the students are more likely to independently continue learning the subjects in which they are interested, even if the courses are over.

- Teachers are hardly identified as the “recipients” of the curriculum, which is not developed by them. They limit their function as teachers only to the correct application of the curriculum. This is the nature of the “top-down” approach, which is pernicious to “the process of taking ownership of the curriculum”;

- Teachers become partners in the process of curriculum transformation. Therefore, they should be given the chance to give input during the initial curriculum design process.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strayer, R. Why Did the Soviet Union Collapse?: Understanding Historical Change; ME Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Platz, S. The Shape of National Time: Daily Life, History and Identity during Armenia’s Transition to Independence 1991–1994. In Altering States: Ethnographies of Transition in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2000; pp. 114–138. [Google Scholar]

- Smolentseva, A. Access to higher education in the post-Soviet States: Between Soviet legacy and global challenges. In Paper Commissioned and Presented at Salzburg Global Seminar, Session; Salzburg Global Seminars: Salzburg, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins, M.; Khachatryan, S. Europeanization in the “Wild East”? Analyzing higher education governance reform in Georgia and Armenia. High. Educ. 2015, 69, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Higher education, sustainability, and the role of systemic learning. In Higher Education and the Challenge of Sustainability; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Kluwer Academic Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Beynaghi, A.; Trencher, G.; Moztarzadeh, F.; Mozafari, M.; Maknoon, R.; Leal Filho, W. Future sustainability scenarios for universities: Moving beyond the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3464–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. How Can Participatory Processes of Curriculum Development Impact on the Quality of Teaching and Learning in Developing Countries; Paper commissioned for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report; United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlacek, S. The role of universities in fostering sustainable development at the regional level. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchin, I.I.; Sima, M.; de Lima, M.A.; Biesel, S.; dos Santos, L.P.; Ferreira, R.V.; Ceci, F. The importance of international conferences on sustainable development as higher education institutions’ strategies to promote sustainability: A case study in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 756–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.P.; Jalal, K.F.; Boyd, J.A. An Introduction to Sustainable Development; Earthscan: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B. The concept of sustainable economic development. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. Making educational development and change sustainable: Insights from complexity theory. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2009, 29, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J. Gorbachev’s Glasnost: The Soviet Media in the First Phase of Perestroika; Texas A&M University Press: College Station, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smolentseva, A.; Huisman, J.; Froumin, I. (Eds.) Transformation of Higher Education Institutional Landscape in Post-Soviet Countries: From Soviet Model to Where? In 25 Years of Transformations of Higher Education Systems in Post-Soviet Countries: Reform and Continuity; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, S.T. Research news and Comment: Will Glasnost Lead to Perestroika? Directions of Educational Reform in the USSR. Educ. Res. 1990, 19, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahverdyan, A. The Mismatch of Higher education (supply) and the labor market (demand). Kantegh A Collect. Sci. Artic. 2009, 3, 249–254. (In Armenian) [Google Scholar]

- Disterheft, A.; da Silva Caeiro, S.S.F.; Ramos, M.R.; de Miranda Azeiteiro, U.M. Environmental Management Systems (EMS) implementation processes and practices in European higher education institutions–Top-down versus participatory approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 31, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonder, R.; Kipnis, M.; Mamlok-Naaman, R.; Hofstein, A. Increasing Science Teachers’ Ownership through the Adaptation of the PARSEL Modules: A “Bottom-up” Approach. Sci. Educ. Int. 2008, 19, 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Leisyte, L.; Westerheijden, D.F. Stakeholders and Quality Assurance in Higher education. In Drivers and Barriers to Achieving Quality in Higher Education; Brill Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Matkovic, P.; Tumbas, P.; Sakal, M. University Stakeholders in the Analysis Phase of Curriculum Development Process Model. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI), Seville, Spain, 17–19 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koehn, P.H.; Rosenau, J.N. Transnational Competence: Empowering Curriculums for Horizon-Rising Challenges; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdanyan, S. Active Learning as a Way to Increase Students’ Motivation. In Conference Proceedings; Armenia-Russian University: Moscow, Russia, 2015. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Higher Education Management and Policy. In Journal of the Program on Institutional Management in Higher Education; OECD Publication Service: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carl, A. The “voice of the teacher” in curriculum development: A voice crying in the wildernes. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2005, 25, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Version 2.3, EBSE 2007-001, Keele University and Durham Univeristy Joint Report; Keele University: Keele, UK; Durham Univeristy: Durham, UK, 2007; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, H.L. The second step in data analysis: Coding qualitative research data. J. Soc. Health Diabetes 2015, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, C. Coding and analysing qualitative data. Res. Soc. Cult. 2012, 3, 367–392. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, H. Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokofiev, M.; Chilikin, M.; Tulpanov, S. Higher Education in the USSR. Vol. Educational Studies and Documents, N39. 1961, Paris: UNESCO. 59. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED544054.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Ghukasyan, A.; Asatryan, L.; Karapetyan, A. “Management of Pedagogical University and Development Trends” Scientific-Methodical Manual; Mankavarzh: Yerevan, Armenia, 2005. (In Armenian) [Google Scholar]

- Silova, I. The crisis of the post-Soviet teaching profession in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2009, 4, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, T.; Polonyi, T. Understanding education in Europe-East: Frames of interpretation and comparison. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2004, 24, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelvys, R. Development of education policy in Lithuania during the years of transformations. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2004, 24, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höltge, K. Governance in Transition. In What Makes Georgia’s Higher Education System So Corrupt? Kassel University Press GmbH: Kassel, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nixey, J. The Long Goodbye: Waning Russian Influence in the South Caucasus and Central Asia; Chatham House: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kivirähk, J. The «Humanitarian Dimension» of Russian Foreign policy Toward Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, and the Baltic States; Centre for East European Policy Studies: Riga, Latvia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Navoyan, A. Tertiary education in Armenia: Between Soviet heritage, transition, and the Bologna Process. In Tertiary Education in Small States: Planning in the Context of Globalization; International Institute for Educational Planning: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdanyan, S. To the Question about Pedagogical Activities at the Higher Educational Institutions. In Conference Proceedings; Armenia-Russian University: Yerevan, Armenia, 2015. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Khachatryan, N. Social Orientation Issues of Professional Education. Kantegh A Collect. Sci. Artic. 2017, 2, 154–167. (In Armenian) [Google Scholar]

- Sekhposyan, A. Problems of Modernization of the Higher Education System in the Republic of Armenia. Master’s Thesis, Defenced at the Public Administration Academy of the Republic of Armenia, Yerevan, Armenia, 2018. (In Armenian). [Google Scholar]

- Petrosyan, H. Issues of Educational Program Accreditation. Lrab. Soc. Sci. 2007, 1, 112–125. (In Armenian) [Google Scholar]

- Karakhanyan, S.Y. Reforming Higher Education in a Post-Soviet Context: The Case of Armenia. Ph.D. Dissertation, Radbound University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2011. [Sl: Sn]. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, T. The History of Armenian Pedagogy, from Ancient Times to the Present Days; Van Saryan: Yerevan, Armenia, 2012. (In Armenian) [Google Scholar]

- Militonyan, L. The Main Approaches to a Professional Modular Educational Program Design; Bryusov State University: Yerevan, Armenia, 2016. (In Armenian) [Google Scholar]

- Stabback, P. What Makes a Quality Curriculum? In-Progress Reflection No. 2 on “Current and Critical Issues in Curriculum and Learning”; UNESCO International Bureau of Education: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, I.K.; Hjortsø, C.N. Sources of complexity in participatory curriculum development: An activity system and stakeholder analysis approach to the analyses of tensions and contradictions. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. Improving forestry education through participatory curriculum development: A case study from Vietnam. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2000, 7, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaeffer, S. Participatory approaches to teacher training. In Teachers in Developing Countries: Improving Effectiveness and Managing Costs; International Institute for Educational Planning: Paris, France, 1993; pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M.; Mulà, I. Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development: Emerging Teaching and Research Developments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruesch Schweizer, C.; Di Giulio, A.; Burkhardt-Holm, P. Scientific Support for Redesigning a Higher-Education Curriculum on Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Espallargas, C.; Ruiz-Morales, J.; Limon-Dominguez, D.; Valderrama-Hernandez, R. Sustainability in the University: A Study of Its Presence in Curricula, Teachers and Students of Education. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, C.R.; Perencevich, K.C.; DiCintio, M.; Turner, J.C. Supporting autonomy in the classroom: Ways teachers encourage student decision making and ownership. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 39, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapleo, C.; Simms, C. Stakeholder analysis in higher education: A case study of the University of Portsmouth. Perspectives 2010, 14, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Student assessment: Putting the learner at the centre. In Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, B.M. Influence of Stakeholders’ Participation on the Success of the Economic Stimulus Programme: A Case of Education Projects in Nakuru County, Kenya. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, L.H.N. Game of blames: Higher education stakeholders’ perceptions of causes of Vietnamese graduates’ skills gap. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 62, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, L.; Shacklock, K.; Marchant, T. Employability: A contemporary review for higher education stakeholders. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2018, 70, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, R. Participatory Curriculum Development in Agricultural Education: A Training Guide: Alan Rogers and Peter Taylor; Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO): Rome, Italy, 1998; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, F.M.; Clandinin, D.J. Teachers as Curriculum Planners. Narratives of Experience; ERIC: New York, NY, USA, 1988.

- Imber, M.; Neidt, W.; Reyes, P. Teacher Participation in School Decision Making Teachers and Their Workplace: Commitment, Performance, and Productivity 1990 Newbury Park; Sage: London, UK, 1990; Volume 67, p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carl, A. Teacher Empowerment through Curriculum Development: Theory into Practice; Juta and Company Ltd.: Cape Town, South Afrika, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, G. Process of Curriculum Development in Pakistan. Int. J. New Trends Arts Sports Sci. Educ. 2016, 5, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brooman, S.; Darwent, S.; Pimor, A. The student voice in higher education curriculum design: Is there value in listening? Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2015, 52, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowler, P.; Trowler, V. Student Engagement Evidence Summary; The Higher Education Academy: Lancaster, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bovill, C. An investigation of co-created curricula within higher education in the UK, Ireland and the USA. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2014, 51, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovill, C.; Cook-Sather, A.; Felten, P. Students as co-creators of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula: Implications for academic developers. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2011, 16, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner Mainardes, E.; Alves, H.; Raposo, M. A model for stakeholder classification and stakeholder relationships. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 1861–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, C. Managerial and Organizational Cognition: Theory, Methods and Research; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Dehli, India, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Keryan, T.; Muhar, A.; Mitrofanenko, T.; Khoetsyan, A.; Radinger-Peer, V. Towards Implementing Transdisciplinarity in Post-Soviet Academic Systems: An Investigation of the Societal Role of Universities in Armenia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šlaus, I.; Šlaus-Kokotović, A.; Morović, J. Education in countries in transition facing globalization—A case study Croatia. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2004, 24, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Title/Publisher | Year of Publication | Study Relevant Codes Applied | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Shaeffer, S. | Participatory approaches to teacher training. Teachers in developing countries: Improving effectiveness and managing costs, pp. 187–200. | 1993 | “curriculum”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 2. | Percy, R. | Participatory curriculum development in agricultural education: a training guide: Alan Rogers and Peter Taylor; Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Rome, 1998, 154p, ISBN 92-5-104272-1. Available free from Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy., Pergamon. | 2000 | “curriculum”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 3. | Platz, S. | The Shape of National Time: Daily Life, History and Identity during Armenia’s Transition to Independence 1991–1994. Altering states: Ethnographies of transition in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union: pp. 114–138. | 2000 | “Armenia”, “higher education”, “post-Soviet countries” |

| 4. | Fullan, M. | The new meaning of educational change: Routledge. | 2001 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 5. | Sterling, S. | Higher education, sustainability, and the role of systemic learning, in Higher education and the challenge of sustainability. Springer. pp. 49–70. | 2004 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 6. | Kozma, T. and T. Polonyi | Understanding education in Europe-East: Frames of interpretation and comparison. International Journal of Educational Development, 24(5): pp. 467–477. | 2004 | “higher education”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 7. | Stefanou, C.R., et al. | Supporting autonomy in the classroom: Ways teachers encourage student decision making and ownership. Educational psychologist,. 39(2): pp. 97–110. | 2004 | “higher education”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 8. | Taylor, P. | How can participatory processes of curriculum development impact on the quality of teaching and learning in developing countries. Paper commissioned for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report | 2005 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 9. | Ghukasyan, A., L. Asatryan, and A. Karapetyan, | Management of Pedagogical University and development trends” Scientific-methodical manual (in Armenian). Mankavarzh. | 2005 | “Armenia”, “curriculum”, “higher education”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 10. | Carl, A. | The “voice of the teacher” in curriculum development: a voice crying in the wildernes. South African Journal of Education, 25(4): pp. 223–228. | 2005 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 11. | Petrosyan, H. | Issues of Educational Program Accreditation (in Armenian). Lraber: Social Sciences. 1: pp. 112–125. | 2007 | “Armenia”, “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “post-Soviet countries” |

| 12. | Blonder, R., et al. | Increasing Science Teachers’ Ownership through the Adaptation of the PARSEL Modules: A” Bottom-up” Approach. Science Education International, 19(3): pp. 285–301. | 2008 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 13. | Mason, M. | Making educational development and change sustainable: Insights from complexity theory. International Journal of Educational Development. 29(2): pp. 117–124. | 2009 | “higher education”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 14. | Shahverdyan, A. | The Mismatch of Higher education (supply) and the labor market (demand) (in Armenian). Kantegh: A collection of scientific articles, 3: pp. 249–254. | 2009 | “Armenia”, “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “post-Soviet countries”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 15. | Silova, I. | The crisis of the post-Soviet teaching profession in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Research in Comparative and International Education, 4(4): pp. 366–383. | 2009 | “higher education”, “post-Soviet countries”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 16. | Carl, A. | Teacher empowerment through curriculum development: Theory into practice. Juta and Company Ltd. | 2009 | “curriculum”, “participation”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 17. | Trowler, P. and V. Trowler | Student engagement evidence summary, The Higher Education Academy. | 2010 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 18. | Navoyan, A. | Tertiary education in Armenia: Between Soviet heritage, transition, and the Bologna Process. Tertiary education in small states: Planning in the context of globalization, p. 193. | 2011 | “Armenia”, “curriculum”, “higher education” |

| 19. | Karakhanyan, S.Y. | Reforming higher education in a post-Soviet context: The case of Armenia. [Sl: sn]. | 2011 | “Armenia”, “higher education”, “post–Soviet countries” |

| 20. | Bovill, C., A. Cook-Sather, and P. Felten | Students as co-creators of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula: implications for academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 16(2): pp. 133–145. | 2011 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 21. | Wagner Mainardes, E., H. Alves, and M. Raposo | A model for stakeholder classification and stakeholder relationships. Management decision,. 50(10): pp. 1861–1879. | 2012 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation” |

| 22. | Simonyan, T. | The History of Armenian Pedagogy, from Ancient Times to the Present Days (in Armenian). Yerevan: Van Saryan. | 2012 | “Armenia”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 23. | Smolentseva, A. | Access to higher education in the post-Soviet States: Between Soviet legacy and global challenges. in Paper commissioned and presented at Salzburg Global Seminar, Session. | 2012 | “higher education”, “post-Soviet countries”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 24. | Disterheft, A., et al. | Environmental Management Systems (EMS) implementation processes and practices in European higher education institutions–Top-down versus participatory approaches. Journal of Cleaner Production, 31: pp. 80–90. | 2012 | “higher education”, “participation” |

| 25. | Nixey, J. | The Long Goodbye: Waning Russian Influence in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. Chatham House. | 2012 | “higher education”, “post-Soviet countries” |

| 26. | Sedlacek, S. | The role of universities in fostering sustainable development at the regional level. Journal of cleaner production, 48: pp. 74–84. | 2013 | “higher education”, “sustainability” |

| 27. | Leisyte, L. and D.F. Westerheijden | Stakeholders and quality assurance in higher education, in Drivers and barriers to achieving quality in higher education. Brill Sense. pp. 83–97. | 2014 | “higher education”, “participation” |

| 28. | Matkovic, P., et al. | University Stakeholders in the Analysis Phase of Curriculum Development Process Model. in Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI). | 2014 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation” |

| 29. | Kazdanyan, S. | Active Learning as a Way to Increase Students’ Motivation” (in Russian) in Conference proceedings. Moscow. | 2015 | “Armenia”, “curriculum”, “higher education”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 30. | Dobbins, M. and S. Khachatryan | Europeanization in the “Wild East”? Analyzing higher education governance reform in Georgia and Armenia. Higher Education, 69(2): pp. 189–207. | 2015 | “Armenia”, “curriculum”, “higher education”, “post-Soviet countries”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 31. | Kazdanyan, S. | To the Question about Pedagogical Activities at the Higher Educational Institutions (in Russian). in Conference Proceedings, Armenian-Russian University, Yerevan, Armenia. | 2015 | “Armenia”, “higher education”, “participation”, “post-Soviet countries”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 32. | Brooman, S., S. Darwent, and A. Pimor | The student voice in higher education curriculum design: is there value in listening? Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 52(6): pp. 663–674. | 2015 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 33. | Militonyan, L. | The main approaches to a professional modular educational program design (in Armenian). BANBER, Bryusov State University,. | 2016 | “Armenia”, “curriculum”, “higher education” |

| 34. | Stabback, P. | What Makes a Quality Curriculum? In-Progress Reflection No. 2 on” Current and Critical Issues in Curriculum and Learning”. UNESCO International Bureau of Education. | 2016 | “curriculum”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 35. | Khachatryan, N. | Social Orientation Issues of Professional Education (in Armenian). Kantegh: A collection of scientific articles, 2: pp. 154–167. | 2017 | “Armenia”, “higher education”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 36. | Sekhposyan, A. | Problems of Modernization of the Higher Education System in the Republic of Armenia (in Armenian). | 2018 | “Armenia”, “higher education”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 37. | Smolentseva, A., J. Huisman, and I. Froumin | Transformation of Higher Education Institutional Landscape in Post-Soviet Countries: From Soviet Model to Where?, in 25 Years of Transformations of Higher Education Systems in Post-Soviet Countries: Reform and Continuity, J. Huisman, A. Smolentseva, and I. Froumin, Editors. Springer International Publishing: Cham. pp. 1–43. | 2018 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “post-Soviet countries”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 38. | Small, L., K. Shacklock, and T. Marchant | Employability: a contemporary review for higher education stakeholders. Journal of Vocational Education & Training,. 70(1): pp. 148–166. | 2018 | “higher education”, “participation” |

| Exceptions: Publications before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 | ||||

| 39. | Prokofiev, M., M. Chilikin, and S. Tulpanov | Higher education in the USSR. Vol. Educational studies and documents, N39, Paris: UNESCO. 59. | 1961 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “post-Soviet countries” |

| 40. | Connelly, F.M. and D.J. Clandinin | Teachers as Curriculum Planners. Narratives of Experience. ERIC. | 1988 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation” |

| 41. | Imber, M., W. Neidt, and P. Reyes | Teacher participation in school decision making Teachers and their workplace: Commitment, performance, and productivity 1990 Newbury Park. CA Sage, 67: p. 85. | 1990 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 42. | Kerr, S.T. | Research news and Comment: Will Glasnost Lead to Perestroika? Directions of Educational Reform in the USSR. Educational researcher, 19(7): pp. 26–31. | 1990 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “post-Soviet countries”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| Revised search results: Studies added after the revised search in 2020 | ||||

| 43. | Alexander, I.K. and C.N. Hjortsø | Sources of complexity in participatory curriculum development: an activity system and stakeholder analysis approach to the analyses of tensions and contradictions. Higher Education, 77(2): pp. 301–322. | 2019 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 44. | Solís-Espallargas, C., et al. | Sustainability in the University: A Study of Its Presence in Curricula, Teachers and Students of Education. Sustainability,. 11(23): p. 6620. | 2019 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “participation”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| 45. | Ruesch Schweizer, C., A. Di Giulio, and P. Burkhardt-Holm | Scientific Support for Redesigning a Higher-Education Curriculum on Sustainability. Sustainability, 11(21): p. 6035. | 2019 | “curriculum”, “higher education”, “sustainability” |

| 46. | Cebrián, G., M. Junyent, and I. Mulà | Competencies in education for sustainable development: Emerging teaching and research developments, Sustainability, 12(2): 597 | 2020 | “higher education”, “sustainability”, “teaching and learning methods” |

| Drivers and Barriers | Description for Figure 5a: The Centralized System of Higher Education in the Soviet Era | Description for Figure 5b: Current Higher Education System in Post-Soviet Member States |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Market | State (Soviet Union) had full control over the production and economy in all the member states. The decisions were made for the whole production value chain in the market. | States (former member states) entered a market economy, which was ruled by the law of supply and demand, so the state partly lost its controlling function over types and quantity of the production in the economy (taxes and laws are a regulating tool). |

| 2. Labor market | The labor market was controlled by the state—identifying need for production types and making decisions on the demand of quantity and types of specialists for the economy. For example, the industrialization of the country required an increase in training of engineers. | The labor market was not an exception. Here again, states had lost their control, and the law of demand and supply had started functioning with significant disorder. The connection of curricula and labor market demand was quite weak. |

| 3. HE management | The state bore all the expenses of the construction of buildings, equipment, salaries to the professors, maintenance of students, and other expenses [31]. | HE state institutions continued to be partly financed by states (and from the tuition fees). |

| 4. Access to HE | Education was mainly from a state stipend. | Tuition fees were applied; a low number of state stipends were still available. |

| 5. Quality of education | The universities were not autonomous. Decisions on the curriculum and teaching and learning methods were made to follow political grounds, and there was no participation in these processes by member states. | Despite to all the changes that occurred during the transition period, HE still continued in the old way of working: curricula were old, educational programs did not meet the labor market demand, teaching and learning methods hardly considered the needs of students, and there was less participation by learners and by practical specialists (stakeholders). |

| 6. Employment after graduation | Each graduate was entitled to a job for one or four years after graduation. | Today, the job market is incredibly challenging for a young, inexperienced graduate in Armenia. |

| Personnel | Curricula | Institutional | Quality Education |

|---|---|---|---|

| -Teacher shortage [33,40,41] -The feminization of teaching profession [33] -An over-aged teaching force [39] | -Planned and politically tied curricula [14] -Poor connection to “real-world” problems [3,14] -Modernization problems (not available for international exchange) [14,16,42] | -Challenging starting point for HE modernization [4,14,16] -Low salaries [40] -Low mobility [4] -Corruption [4] -Not well-researched [14] -Decrease of enrollment in teacher education programs [41] -Low transition rate from teacher education graduation to professional service [41] -Separation of teaching and research [40] -High concentration of HEIs in the capital city [40] -Lack of international standards fulfilment [4,41,43] -Hierarchical structures [44] | -Incompatible or poor teaching quality [4,44] -Lack of infrastructure and technology [45] -Lack of library resources and research laboratories [42] -Obligatory preparatory lessons for admission examinations [22,46] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hovakimyan, H.; Klimek, M.; Freyer, B.; Hayrapetyan, R. Sustainable Shift from Centralized to Participatory Higher Education in Post-Soviet Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105536

Hovakimyan H, Klimek M, Freyer B, Hayrapetyan R. Sustainable Shift from Centralized to Participatory Higher Education in Post-Soviet Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105536

Chicago/Turabian StyleHovakimyan, Hasmik, Milena Klimek, Bernhard Freyer, and Ruben Hayrapetyan. 2021. "Sustainable Shift from Centralized to Participatory Higher Education in Post-Soviet Countries: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105536

APA StyleHovakimyan, H., Klimek, M., Freyer, B., & Hayrapetyan, R. (2021). Sustainable Shift from Centralized to Participatory Higher Education in Post-Soviet Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 13(10), 5536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105536