Abstract

This article explores the changing values of heritage in an era saturated by an excess of media coverage in various settings and also threatened by either natural or manmade disasters that constantly take place around the world. In doing so, we focus on discussing one specific case: the debate surrounding the identification of Sungnyemun as the number one national treasure in South Korea. Sungnyemun, which was first constructed in 1396 as the south gate of the walled city Seoul, is the country’s most acknowledged cultural heritage that is supposed to represent the national identity in the most authentic way, but its value was suddenly questioned through a nationwide debate after an unexpected fire. While the debate has been silenced after its ostensibly successful restoration conducted by the Cultural Heritage Administration in 2013, this article argues that the incident is a prime example illustrating how the once venerated heritage is reassembled through an entanglement of various agents and their affective engagements. Methodologically speaking, this article aims to read Sungnyemun in reference to the growing scholarship of actor-network theory (ANT) and the studies of heritage in the post-disaster era through which to explore what heritage means to us at the present time. Our synchronic approach to Sungnyemun encourages us to investigate how the once-stable monument becomes a field where material interventions and affective engagements of various agents release its public meanings in new ways.

1. Introduction

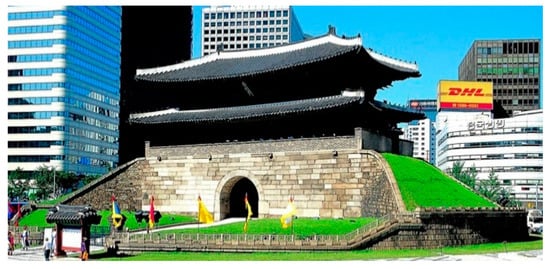

In this article, we explore how heritage becomes entangled with disasters and thus brings forth new layers of meaning that are not so much derived from a set of preestablished criteria but rather emerge through an assemblage of both human and nonhuman agents, material and immaterial forces and intensities. In doing so, we conduct one case study: the unexpected arson of Sungnyemun (숭례문; 崇禮門), one of the most significant heritage sites in South Korea, which has been designated as the number one national treasure (kukbo; 國寶) in 1962 (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The primary materials that we analyze include a set of debates dealing with its identification as national treasure and related images taken before, during and after the fire. This investigation also enables us to examine how heritage damaged by disasters, either natural or manmade, could bring forth senses of community which encourage us to rethink the values of heritage from multiple perspectives in resonance to changing worldly atmospheres and technicalities.

Figure 1.

Sungnyemun and its surrounding landscape before the 2008 arson (Source: Jung Gu of Seoul and author edited) [1].

Figure 2.

The restored setting of Sungnyemun after the arson (Source: Cultural Heritage Administration and author edited) [2].

Sungnyemun is one of the eight gates displaced surrounding the castle city, and has functioned as the south gate of Seoul that was constructed in 1396, which is two years before the establishment of Joseon Dynasty (1398–1910). Those eight gates were connected to each other by a circular continuous wall, and are usually grouped by four main gates and four smaller ones, respectively, according to their significance and size. Sungnyemun is one of the four main gates, and the others include Heunginjimun (興仁之門) in the east (also called Dongdaemun), Donuimun (敦義門) in the west, and Sukjeongmun (肅靖門) in the north of the city. Sungnyemun was the most important entry point to the city, which is also a symbolical axis connected to Gyeongbokgung Palace (景福宮) that was the primary administrative place of the Dynasty.

Structurally speaking, Sungnyemun consists of upper and lower parts. The lower part is connected to the surrounding walls and has a vaulted gate at the center; and the upper part consists of a timber gatehouse of five bays in the front and two bays on the side [3]. However, as the city was severely damaged during the Japanese occupation (1910–1945), Sungnyemun as part of the continuous wall became compartmentalized as if it were an isolated object. While Sungnyemun had long been considered the number one national treasure despite its devastation during colonialism, another disastrous event took place which ultimately urged to rethink its value in toto. It is an arson instigated by a man named Chae Chong-gi on 10 February 2008. The arson destroyed 90% of the timber gatehouse and 10% of the lower stone structure [2]. The repair process was immediately executed, but the incident also instigated a nationwide debate as to whether or not the restored gate should still be considered the country’s number one national treasure (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

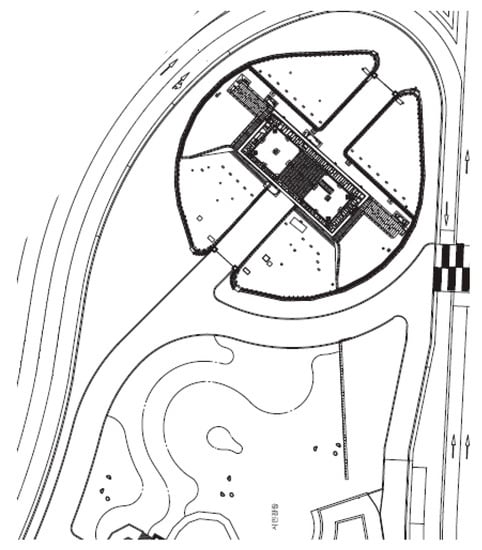

Figure 3.

The plan of Sungnyemun published in the 2006 survey report (Source: Jung Gu of Seoul and author edited) [1].

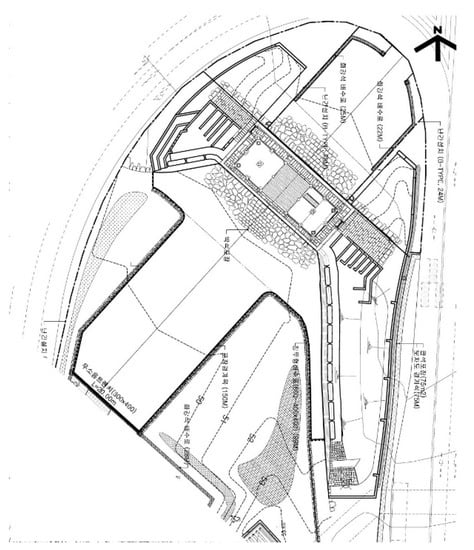

Figure 4.

The plan of the restored Sungnyemun after the fire published in the 2013 survey report (Source: Cultural Heritage Administration and author edited) [2].

Through an in-depth investigation of the debates and the related materials that unfolded during and after the arson, we aim to explore the shifting value of heritage in an era in which a diverse range of media prevail. What we mean by “media” is defined in a broad sense, which includes apparatuses mediating the domains that are both human and nonhuman, as well as the strata of the everyday that are both bodily-oriented and virtual. While the Internet and social network services (SNS) are one kind of media enabling us to have synchronous experience of everyday incidents, one still finds material evidence such as administrative documents and printed photographs useful. In addition, we also pay attention to other sorts of technical media such as survey reports, 3D scan data, and BIM (Building Information Modeling), which help to reconstruct a given heritage’s idea and its physical structure with precision. Using such media for our investigation of Sungnyemun is important, because judging the value of a heritage that is materially grounded, often designated as “tangible cultural property”, is not entirely based on its historical features but also considers present conditions and situations, which may be subject to frequent changes. Sungnyemun is a monument standing at the center of the Seoul metropolis. Its surrounding features such as skyscrapers, roadside buildings, and other infrastructural elements such as roads, electric poles, billboards, and neon signs are also factors to consider in establishing its value in the urban context. The gate is also a mnemonic apparatus reminding Korean citizens of the establishment of the Joseon Dynasty, its colonization by Japan in early 20th century, the civil war (1950–1953), and the subsequent modernization processes from the 1960s to the end of the century, all of which evoke their nationalist sentiments or at least offer some grounds to speculate on the open relationship between individuals and the nation to which they belong in one way or another. An individual encountering a heritage resource in the present time does not necessarily share the same kind of experience as was in the past. However, would it mean that such an experience is less authentic than that in the past? Put differently, is our experience of Sungnyemun less authentic compared to the one that occurred when the structure was new in 1396? We claim that it is not always the case. We do not mean to devalue the originality of heritage, instead claiming that judging the value of heritage in everyday life inevitably requires taking into consideration its changing nature (ICOMOS, 1994) [4].

Paying attention to the changeability of heritage encourages us to take disasters not just as destructive events in a negative sense but as something that influences its perpetual reestablishments in relation to incidents that are beyond instrumental approaches to the heritage. Here, the term “post-disaster” is understood as a state of disequilibrium, an unstable but hopeful situation, and also a possibility of rethinking familiar things, which becomes public debates and private interactions taking place on both online and offline spaces [5]. Meanwhile, as Tomasz Jeleński notes in the contexts of postwar Europe, “resilience” is another term explaining how heritages in post-disaster situations could be moments of rebuilding “traditional images of cities after their mutilation in disastrous events” [6]. Jeleński’s way of seeing heritage is not unusual, as several heritage studies highlight the interactivity and openness of heritage, as well as the affectivity that arises in post-disaster situations, some of which are reviewed in this article. In analyzing the politics behind the reconstruction of the Royal Castle in the postwar Warsaw, Poland, Ewa Klekot claims that the construction of a monument does not simply end up with its material establishment but is rather “a continuous process carried out via” various forms of practice performed by administrators, architects, visitors, and other agents [7]. In a similar vein, Trinidad Rico notes that reconstructing damaged heritages after disasters deals with contemporary concerns over their authenticities already established. Analyzing the “post-tsunami reconstructions in Banda Aceh, Indonesia, between the years of 2006 and 2011”, Rico argues that concerns with the future wellbeing of the damaged heritage challenge the essentialist viewpoints on heritage and thus bring forth new values that unfold through continual documentations and communications [8]. The kind of value would include not only projects instituted by governments but also a number of disparate “plaques” inscribed with messages such as “Thank You” and “Peace” that are located on a public square within the site [8]. What is highlighted in such an “expanded assemblage of commemoration efforts”, as Rico nicely described it, is “affective atmospheres” as Palu Cloke and David Conradson address on a similar occasion, a series of earthquakes that took place in the city of Christchurch, New Zealand, from 2010 to 2011. They focus on discussing how artists and other members of the community affectively engage with each other in order to generate shared senses of being together, which would challenge those who tend to consider post-disaster recovery simply as a “material and measurable” project [9]. In the meantime, endeavors of generating affective atmospheres become more important in Asian countries such as Japan, China, and South Korea where “materiality is [fundamentally] impermanent” (i.e., heritage structures constructed from wood that is highly susceptible to fire) [10,11].

In exploring the shifting values of heritage in the post-disaster era especially in the East Asian contexts, we propose to conduct the following three bodies of work. The first is to review the key tenets of Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory (ANT), and explore how the theory is still helpful for us to reconceptualize heritage in new ways. Second, we investigate the historiography of Sungnyemun, in particular focusing on analyzing the debates that address how the historic gate should be restored and reconceptualized after the 2008 fire. Our investigation is not merely a historical survey but an attempt to explore its multiple dimensions which bring forth an assemblage consisting of interventions made from the top, bottom and virtually anywhere in differing rhythms and intensities. Third, we go further by attempting to interpret Sungnyemun through a comparative analysis of two crucial survey reports and associated photographs illustrating the structure before, during, and after the 2008 incident, which enables us to explore how the seemingly stable monument put on a pedestal could open up meanings that are fundamentally generative and interactive.

2. Rethinking Heritage through ANT

One of the key aspects to understand ANT is the term “actant”, which is equivalent to “actor” but not limited to humans. In defining the term, Latour introduces the example of a “speed bump” that is used to restrict vehicle speed. The following paragraph shows how he understands speed bump as a threshold to explore an actor-networked world:

“In artifacts and technologies we do not find the efficiency and stubbornness of matter, imprinting chains of cause and effect onto malleable humans. The speed bump is ultimately not made of matter; it is full of engineers and chancellors and lawmakers, commingling their wills and their story lines with those of gravel, concrete, paint, and standard calculations. The mediation, the technical translation, that I am trying to understand resides in the blind spot in which society and matter exchange properties”.[12]

Reminding that a speed bump is often called a “sleeping policeman” in French culture (also in UK and US), Latour suggests how this ostensibly tiny infrastructural element could instigate a social network [12]. The speed bump does not so much directly instruct actions but rather induces a mode of spatial cognition and behavior through a mnemonic technique. It manifests itself through apparatuses such as colored asphalt patterns on the ground and a “slow your speed” sign, which illustrate how a disciplinary system is materially inscribed. The speed bump is a bureaucratic mediator in the sense that it prevents possible accidents and accommodates a nation’s social sustainability. However, one cannot simply assume that those driving automobiles or bicycles would all follow it in the same manner. While someone perceives a speed limit of 10 km/h by looking at the sign properly, some others might pass it through by driving at over 30 km/h. In the latter case, the disciplinary system mediating speed bump is encountered in a rather unexpected way, which offers a way to investigate the disparity between a nation that establishes a rule and individuals who follow it in various situations. If the action of a driver who crosses it at 10 km/h is a normative kind, crossing it at 30 km/h is, according to Latour, “another kind of expression” responding to a given rule. It is difficult to set up a pre-established hierarchy between these two, and a society established according to myriad actions and events is similar to “what is glued together by many other types of connectors” put under the state of fragmentation and fluidity [12,13] (italic original).

Latour’s concept (ANT) is a good avenue to rethink the instability of system, discipline, and any kind of thing comprising the world, which is not unrelated to the concept of heritage that we aim to elaborate. According to Julia Bennett who investigates the meaning of place at Bickerton Hill (UK), “ANT provides a flat surface on which to draw out the different themes of the story” [14]. She lists up a range of human and nonhuman agencies in analyzing the hill, which includes “The National Trust, government departments and agencies, big weeds [played here by birch trees], various wild, farmed and domestic animals” [14,15]. When residents participating in a meeting held for the preservation of the hill claim that “[t]he trees also ‘speak up’”, it means their attitude that is attentive more to the entanglement of nature and culture, and human and nonhuman things than the clear-cut separation between them [14]. According to Bennett who applies ANT to her own research, Bickerton Hill is a material to be implemented for project and also a source of nostalgia for the residents. She calls such an unstable entity consisting of thoughts, feelings, actions, and events “heterogeneous assemblages” [14]. Her conception of assemblage reflects a worldview of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, which is similarly detected in the work of Matthew J. Hill who analyzes the Plaza Vieja of Havana. Claiming the notions of “heritage as a ‘mediator’” and “heritage assemblage”, Hill understands heritage not as a mere collection of disparate relics and historic sites but as a resilient field where things are perpetually reassembled and release differing spatiotemporal dimensions. The project’s long-term delay due to the conflicts of opinion between stakeholders moves on and generates unexpected results through the “chain of permissions and refusals, alliances and losses” [16,17].

Meanwhile, Chin-Ee Ong brings a rhizomatic way of thinking into the practice of heritage through his definition of “heritage-scene”. The term “rhizomatic”, also derived from the work of Deleuze and Guattari, means a non-hierarchical, groundless but consistent mode of being, in ways to imbricate more instable but flexible relationships with things scattered around the world. Ong does not distinguish culture from nature that is characterized by its complex network made up of tiny organs. According to him, “heritage-scene” is “an amalgam of inspirations, interactions and negotiations between objects and ideas, stuff and mind and between the community which foment and forge the ritual, performance and objects and their various stakeholders” [18]. In articulating the value of intangible cultural asset such as a coffee artisan who has worked in the Georgetown area of Malaysia, he proposes to consider all the elements including coffee as raw materials, apparatuses, and places in an integrated way, which can be applied to the kinds of cultural asset that are both tangible and intangible [18,19]. The number of ANT-inspired heritage studies has consistently increased in the past decade. According to Harrison who summarizes such a fashion under the subheading called “Heritage, New Materialities, and New Ontologies”, the ANT method emphasizes “on more symmetrical approaches to understanding the distribution of different forms of agency across heterogeneous networks which include both human and other-than-human actors” [19].

One of the crucial implications derived from the ANT approach to heritage studies is that the value of heritage is not so much judged simply based on a set of pre-established criteria but rather constantly reconsidered through careful investigations and skeptical attitudes, even if such a process might, as Latour notes, perform on a “bumpy territory” in an “agonizingly slow” manner [13]. As cultural assets and a wide range of cultural heritages change over time, there are many ways in which one comes across heritage sites as part of our daily lives. While the concept of heritage can be established through the collaboration between those working with international organizations such as UNESCO and ICOMOS, it also needs readjustments according to each country’s specific cultural contexts. We are also attentive to the disparity between cultural assets designated by laws and their societal values. Then, would it be possible to further speculate on the meanings of heritage in reference to Latour’s metaphor of “speed bump”, Rico and Bennett’s “assemblage”, Cloke and Conradson’s “affective atmosphere”, and Ong’s “heritage-scene”? Looking at the King Sejong monument located at the center of Seoul’s Gwanghwamun Square is a relevant example in this respect.

What makes the Gwanghwamun Square peculiar is first of all its urban formation, a narrow and elongated spatial form that was implemented during the administration of Oh Se-hoon as Mayor of Seoul (2006–2011) (Figure 5). The Square is located at the core of the old Seoul, once a walled city in the pre-modern era; Gyeongbokgung Palace is located at its north alongside the Bukhan mountain in the background; on its south is the Cheonggyecheon stream, reinstated following demolition of a highway in 2005, which cuts across the city on the east–west axis. At the center of the Square, there is also the monument of King Sejong (1397–1450) who is best known for his contribution to creating hangeul, meaning the “Korean alphabet”, which symbolizes one of the crucial components of national identity among others. This monument is elevated on a pedestal, and delivers a substantial impression to visitors due to its massive scale and symbolism. Hangeul as cultural heritage is recreated as a material inscription representing the King Sejong who created the 28 letters of Hunminjeongeum in 1443, a book describing an entirely new system of Korean language that is still used. This highly venerated figure is a grandiose monument that shapes one’s bodily encounters within and around the square area.

Figure 5.

A bird’s-eye view of Gwanghwamun Square (Source: The Seoul Research Data Service and author edited) [20].

Another noteworthy point is that the monument is also used as a popular photo zone for visitors including tourists (Figure 6). Visitors can cheaply rent hanbok (meaning the traditional Korean dress) under $10 for a couple hours and freely move around and take photographs by standing around the monument. However, what is equally true is that the monument is most often part of the daily cityscape or an object that one simply passes by: this kind of engagement brings forth a sense of indifferent relationship with the monument. One would not also dismiss the temporary structures built alongside the lower part of the square in commemoration of the recent tragedy of the Sewol Ferry (2014), in which 304 people died. Those structures are located near the monument, and what happens thereafter is the coexistence of the monument of King Sejong representing Korea as a country having a deep historicity on the one hand and the civil society that is critical about its corruptions on the other hand. Such a coexistence may simply be an undesirable kind viewed from the perspective of city governors and administrators dealing with cultural heritage, but the clash between the contrasting elements could also bring forth positive senses which encourage one to look back how to read given heritage in relationship with changing moods and affects.

Figure 6.

The street view of Gwanghwamun Square in front of the King Sejong monument (Source: the author [S.P.]).

Considering such flexible situations of heritage and their intricate relationships with the dynamism and instability of the city, we claim that heritage consists of many different things, including concepts, rules, gestures, affects, and a variety of practices in both material and immaterial senses. In other words, heritage is constantly updated and modified in relationship with a set of networks that are formed at the crossroads of certain institutions’ disciplinary interventions and various individuals’ engagements with or indifferences about them. Inasmuch as one is not able to anticipate the kind of variables influencing the formation of heritage in advance, anything existing out there in the world could possibly be a candidate for considering as heritage. In this respect, looking at the set of debates around Sungnyemun will open up ways of speculating heritage and its accompanying “scenes” that are simultaneously past and present, material and discursive which constitute an expanded horizon of meaning, although such a horizon is always left incomplete, and ready to be resettled in contact with new things.

3. Key Debates of the Sungnyemun Arson

Then, what are the specific debates that have arisen around the year 2008 when the unexpected arson happened? Before investigating the details, we would like to briefly examine the administrative mechanisms for dealing with heritage in Korea. The first is the convention that distinguishes cultural asset from cultural heritage. A “cultural asset” is defined according to the policy known as “Cultural Heritage Protection Act (2015)”. The Act categorizes historically significant things such as national treasure, treasure, tangible/intangible cultural asset, and natural monument according to a set of numbering systems so that the government can control the type, scale, and number of each asset in systematic ways. Meanwhile, the concept of cultural heritage is more generic and broader than that of “cultural asset” relatively speaking. According to the National Institute of Korean Language, cultural heritage “includes aspects of science, technology, habit, and norm that are worth inheriting for next generations, various kinds of cultural assets or styles that are either spiritual or material, all of which could help establishing the values that could be descended to the society in general” [21]. According to this definition, cultural heritage, even if not designated according to the aforementioned Protection Act, includes a range of things that are worth protecting and preserving.

However, the distinction between cultural asset and cultural heritage is not clearly addressed, which causes continuing confusions. There are also beliefs that assets designated some time ago are considered more significant than newly designated ones, because the former are ranked higher than the latter in number. In addition, it is crucial to note the way that national treasure is understood, which refers to a type of cultural asset designated through the Cultural Heritage Protection Act. Article 23 of the Act (on the designation of treasure and national treasure) states that:

- The Administrator of the Cultural Heritage Administration may designate important cultural heritage as treasures, following deliberation by the Cultural Heritage Committee.

- The Administrator of the Cultural Heritage Administration may designate cultural heritage of great importance for humanity and without parallel in history, among treasures under paragraph (1), as national treasures, following deliberation by the Cultural Heritage Committee [22].

The above Article considers national treasure as the most significant cultural designation among others which could be applied to Sungnyemun. However, this categorization is debatable, since it implies that only “tangible” cultural properties are considered for the designation of national treasures. What was thereafter discussed among the public (after the 2008 arson of Sungnyemun as to the issue of re-designating national treasure) was an idea that hangul (meaning the Korean alphabet) could be a new candidate. However, conceptualizing hangul is an even more complex task: it is because each one uses and understands the term “hangul” differently, upon which we discuss further below. There are three different ways of understanding hangul overall. The first is to understand it as an intangible linguistic system. Hangul as an act of speech, which is generated out of one’s pronunciation through his/her oral movement, has a long history that is, however, not fully traceable in essence. For this reason, Hangul is not designated as a cultural asset. The second is to consider hangul as an alphabet, which was created in the year 1443 specifically by King Sejong; “this” hangul is called hunminjeongeum, which is likewise not yet designated as a cultural asset. The third is to understand hangul as a book, which includes the principles of its creation and the user’s guideline. The book is called hunminjeongeum as well, which is designated as national treasure number 70 and was registered under UNESCO world heritage in 1997 (there is only one copy available of “this” hangul as a book format according to the 2008 survey).

When Korean citizens argued to replace Sungnyemun as the number one national treasure with hangul, their logic is grounded on its second definition, as an alphabet. However, hangul as an intangible property cannot be a national treasure according to the existing laws. An alternative was then proposed that the third, hunminjeongeum, could be a new candidate for designation as a national treasure. However, one needs to be reminded that national treasure is not exactly the most significant heritage, since there are many culturally valuable things including intangible cultural assets and national monuments but these are simply grouped under different categorizations. There was also a suggestion that Sungnyemun’s devastation could be an opportunity to clear out the uncomfortable history with Japan, given that its nomination was first executed during the colonial period. Put differently, the idea relating Sungnyemun to the colonial past evidences a strong nationalist sentiment which is visualized through this idiosyncratic and fortuitous case. Despite all, we claim that the arson as an actant provoked a crucial opportunity in rethinking the value of heritage no matter how it is treated according to a set of administrative systems. The arson instigated the public debate within which various individuals could speak up and speculate about new ways of thinking about heritage in the present tense.

The total amount of money spent for the Sungnyemun restoration is about 24 million dollars (276.6 billion won in Korean currency). Its restoration took place from February 2008 to April 2013. Its details include the restoration of gatehouse and fortresses on both left/right sides, protection against disasters, and an addition of administration building. The construction was processed in consultation with the 2006 survey report published before the arson, which featured the use of 3D scan data and also 3D laser scanning enabling restoration through virtual media. The key principle was to “restore Sungnyemun back to the conditions in the pre-colonial era and thus make it a firm landmark of Seoul, [as well as] taking care of Korean citizens’ senses of loss and self-dignity” [23]. The Cultural Heritage Administration articulated six principles to guide the restoration [23]:

- Restore the image of the gate before fire.

- Make best of reusing the existing materials.

- Restore the fortress and ground back to the original which were heavily distorted and transformed during Japanese colonialism through historic investigations and excavations.

- Restore the structure by using traditional methods and tools as well as by encouraging specialists to participate in the process.

- Organize a counseling team for the project which consists of specialists from the academia.

- Let the Cultural Heritage Administration take responsibilities of financing, technical support, and construction under the central government’s direct management.

Despite the fact that the project was completed according to the principles, we are attentive to the debates around Sungnyemun that are still not fully resolved. Sungnyemun was designated as the number one treasure in 1933 and as the number one national treasure in 1962 [24,25]. According to the administrative report published after the arson, “citizens and mass media were highly interested in the disastrous occurrence given its significance as the number one national treasure, although such a numbering system does not reflect the order of significance in itself” [23].

However, situations around the restoration process were not so simple and smooth, owning to a diverse set of opinions that are difficult to move toward a stable consensus. Some issues also arose during the restoration itself. The incident that Shin Eung-soo, the great carpenter who is a specialist of traditional wooden architecture and also designated as an intangible cultural asset in Korea, stole wood materials for his other projects is one fragment of the story [26]. Another case is an unbalanced use of techniques between traditional and modern, which led to a dispute as to the quality and reliability of the gate being restored [27]. Some others pointed to the fact that the destruction of so much of the upper section itself established the loss of its historic value. Debating over the importance of the amount of original remaining structure in making judgments about heritage value is also area-specific to a certain degree, by which we mean that wooden heritages produced in East Asia are fragile and short-lived, and thus the criteria that designate damaged heritages inevitably vary [4,11,28,29,30,31].

Moreover, much of the debates is not so much about the restoration process as its result. “The restoration of Sungnyemun”, notes journalist Roh Hyung-suk, “does not make the heritage as a crucial point to help remedying the deep remorse and sense of loss caused by the arson that took place five years ago, as well as putting forward a conversation with the past” [32]. What is implicit in his remark is a critical self-reflection about the recent past that several restoration projects were executed with emphasis on result instead of process. As Roh shows, what has most often been pointed out in national debates is an idea of the nation as an ethnic community, whereas the contrasting issues such as refugees and multicultural communities are relatively ignored. Although it might be an exaggeration to put such social issues and the Sungnyemun restoration on the same plane, we claim that its fire became a vital moment in revealing how strong nationalist sentiments prevail in the country, and how such sentiments guide new public projects into certain directions where senses of hospitality and sympathy are partially considered.

In the meantime, we also find Codruta Cuc’s interpretation of the 2008 arson useful in further developing the public meanings of Sungnyemun sparked by someone whose nationality is other than Korean. Cuc argues that trying to research the “origin” of Korea is in fact a byproduct of the reformation era, which refers to the Park Chung-hee administration (1961–1979). According to Cuc, Park’s development strategy that resulted in the compressed modernization process over these decades helped to bring forth an invented tradition, which is a collective identity that can be represented by a phrase such as “we are one” (ulineun hanaya), referring, for example, to the temporary unification of north and south soccer teams prepared for the Olympic Games. The same logic holds true for the case of Sungnyemun [33]. What is worth noticing in Cuc’s argument is an idea that tries to overcome the crude binaries between good and bad, or agreement and disagreement, since her theory identifies that there was no such thing as an ethnically homogeneous nation that the Park regime emphasized, which is no more than a byproduct of bureaucratic and also Confucianism-inspired modernity, and perhaps biopower that was coined as a way to psychologically cope with the postwar conditions in the latter half of the twentieth century. As she nicely explained, “how a certain heritage appears to the public, is defined, explained, shown, and communicated” in relationship with various agents of power whose capacities or actions are unpredictable [33]. What we would like to add on top of this argument is that the kinds of agent associated with heritage are both human and nonhuman, and dismissing such an extended range would fail to grasp the complexity that unfolds at the crossroads of multiple agential interventions put in relation to dispersed heritages.

4. A Reassembled World through the Sungnyemun Debate

Cuc’s critique opens up an avenue to rethink the multiple dimensions of Sungnyemun as a familiar but surprisingly little-known heritage in more flexible ways. Although there was a mutual agreement that Sungnyemun should be restored after the disaster, there was insufficient questioning as to “why” it should be and “how” its process could be meaningful to various groups of people. The project entails a set of agents, including city officials, researchers, salarymen, and shopkeepers who live nearby, and myriad individuals whose voices float around on online and offline spaces. Considering that ANT is attentive to both human and nonhuman agencies as crucial impetuses in shaping the world we live in, various individuals’ actions and their material/immaterial inscriptions, be they institutional or not, human or nonhuman, are likewise crucial to examine. By the same token, such an entanglement establishes what Latour calls a “parliament of things” through which myriad things establish the public sphere that is at once institutional and improvisational [34]. In further articulating this line of thought, in the rest of the article we focus on analyzing the following two issues: first, comparing and contrasting two survey reports of Sungnyemun, which offers a way of reconsidering Sungnyemun to be an assemblage that reflects primary governmental interventions in a systematic way which is, however, porous and opened up for multiple lines of interpretation; and, second, using photographs of the site during and after the fire as thresholds to shape an affective territory, which is put in contrast to another representative space of Seoul to which less attention was usually paid due to its non-monumentality and everydayness.

The first is to overview two practically crucial survey reports that were used for, and after, the restoration of Sungnyemun, published in 2006 and 2013, respectively. Survey reports are a widely used research methodology and also kind of raw data that documents given object or building in the most objective ways. Its documentation process is strictly based on an already established set of survey methods. What we are attentive to is, however, not the detailed methods of documentation but its open-ended mode of translation prompted by a set of different actants, which entail a network composed of key players, namely the heritage being documented, investigators, survey report (as a final product), readers, and other related materials. The investigator dives into the already-formed network and has a limited capacity to interact with it, thereby being able to translate given materials according to a set of carefully implemented guidelines. The survey report is also a method of description that usually consists of texts, photographs, and drawings. The object that the report deals with is different from its textual description due to the nature of media and ways of mediation [35]. Whereas readers are provided ways to deal with the report in new ways, its format is quite dry and based on the idea of representation, or a system of signification in which any elements of uncertainty and improvisation are minimized in preference to consistency.

While the 2006 survey report is a product made in consideration of possible future restoration, that of 2013 is more focused on a set of technical guidelines that can be immediately applied to and also carefully describe the value of Sungnyemun [1,36,37]. These two reports include an extensive range of numerical data and structural system of the gate, as well as its current state as the designated number one national treasure. However, would reading this kind of rule-governed material necessarily lead to a unidirectional reception? According to Latour’s idea of “technical mediation”, we claim that these survey reports can still be a helpful platform to explore the past, present, and future of Sungnyemun. In claiming the openness of such survey reports, one would take advantage of looking at how each report is constructed and how it is differentiated from each other. In doing so, reading a table of contents could be helpful, despite the fact that its arrangement of materials may be technically driven and also generic. Titled A Precision Survey Report of Sungnyemun Gate, the 2006 report has the following table of contents: color figures, survey process, history, displacement, architectural style, architectural planning, precision survey of each component, other surveys, conclusion, figures in black and white, plans, and references. It was made for those who want to know the values of Sungnyemun. The report is a medium helping them to understand the gate before the fire, which is to say a stable monument undisturbed by other considerations and thus assumes a closed community that comprises of the main object, investigator, survey report, and readers in a limited sense. What is highlighted is a normative narrative implemented by a bureaucratic agent which is Jung Gu of Seoul (gu means “ward”; Jung Gu therefore means one of the 25 wards comprising Seoul), and its unidirectional delivery of message makes the report mostly instructive.

In contract, the 2013 report is slightly differentiated from the previous one due to some reasons. Entitled A Repair Report for the Construction of Sungnyemun Restoration and the Castle Restoration and produced by the Cultural Heritage Administration, the report consists of project summary, a series of construction processes for restoration, and an appendix. The aim of the report is to technically describe the value of Sungnyemun, and to illustrate how successful the repair process proceeded from the start to its completion. Its author focuses on demonstrating that the work team was able to restore the gate to almost exactly its condition before the fire. On the other hand, the reader is in a relatively weak position to follow what is implemented without fully being able to know the minute details about the restoration process. Put differently, the report is filled with all the technical methods and empirical data, which need a careful and professional decoding process. An interesting point to note is the contrast between the number of publications on Sungnyemun before and after the fire. Between 1962 and the 2008 fire, there were only five books and reports on Sungnyemun, but this number increased significantly to more than 30 between 2008 and 2015. Such a change indicates people’s growing interest about the heritage after the incident. The 2006 report was a preparatory kind that was made for an unanticipated point in future, whereas the latter is much more practically oriented so that any elements unnecessary for restoration were removed, which is demonstrated by the simpler arrangement of the table of contents (for instance, a “history” section is not included in the main document). However, this does not mean that the 2006 report is more interactive than the latter; the former is similarly written in a dry tone and follows a rather clichéd structure as if the consideration of readers was almost a byproduct. There is a “network” in the 2006 report, but it is a closed kind so that the number of players instigated by the publication is limited. The 2013 report is likewise dry and difficult to interact with, but, ironically, it became a kind of open-ended platform where important data about restoration are included, which could possibly be extended into new territories through an interaction with other agents. One can find such an extended territoriality by further excavating how photographs of Sungnyemun circulating via media worked as momentums to bring forth various ideas, feelings, and events during and after the fire.

Comparing two photographs before/after the fire drawn from two aforementioned reports can be another good point of exploration in this respect (Figure 1 and Figure 2). In the 2006 photograph, Sungnyemun stands mostly disconnected from the pedestrian walk area as if a monument were put on a pedestal in a museum. What is also noticeable is the greenery consisting of two spatial layers. In addition, if the outer layer made of greenery is accessible to pedestrians, this is not the case for the inner one which is protected by a “Do Not Enter” sign. This seemingly minute detail reflects how it had long been treated as an object not accessible for the general public, which seems unrelated to the arson but might be a factor in it. Meanwhile, the 2013 photograph shows a slight difference, partly because the separation between two strata of greenery is no longer obvious, instead illustrating a widened and paved pedestrian area finished with tiles on the ground. Visitors can relatively freely pass through the vaulted area at the center and move around. In addition, another big difference is that the restoration of the surrounding castle walls in the lower part was carefully implemented, although still within the given spatial realm.

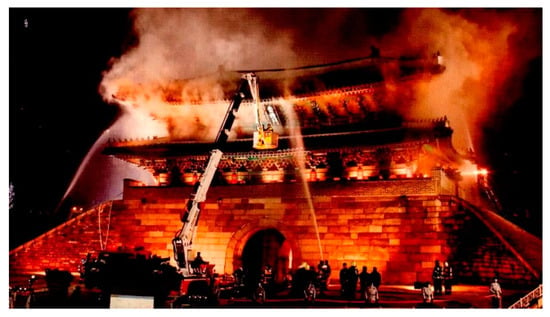

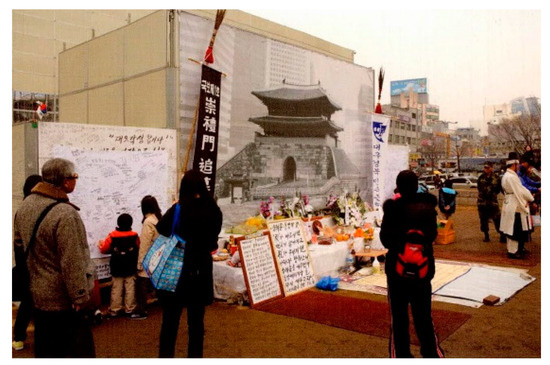

Meanwhile, we find that myriad photographs capturing the moments of condolence for the devastation of Sungnyemun right after the incident, and the ones taken right at the fire scene are crucial materials in rethinking the meaning of heritage in an era characterized by a multitude of Internet and post-Internet platforms are always in excess (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The photograph capturing the moment of the fire being extinguished evoked the nationwide, perhaps worldwide, sentiments as circulated by various media including newspapers, television, tweets, etc. Although Sungnyemun was always there as a designated heritage, it has likewise remained unnoticed. A monument that is grand and symbolic may mean something to us, but such obvious symbolism and physical magnificence could also be dismissed at any time paradoxically speaking. This way of speculating about Sungnyemun reminds us of Robert Musil’s claim that monuments “de-notice us” in the course of everyday life [38]. However, such an invisible presence becomes suddenly visible when things do not work out properly, or something critical happens, which is the case for our example. Mass media had continuously broadcast the real-time progress of its extinction, and the visual spectacle offered an opportunity for those who were not usually interested in the monument to take a look at the gate and its surroundings probably for the first time in their lives. Senses of condolence and sympathy unfolded in resonance to these kinds of photograph, but looking at familiar things anew is another parameter that is worth noticing. Put differently, these photographs instigated collective memories and affects at the very moment of its ongoing disappearance broadcast on media. Photographs taken during the fire were mostly documentary by nature, which lasted relatively in a short period of time but nevertheless helped forming a loose sense of community that prompted new ways of seeing this familiar but idiosyncratic monument that is at once near and far.

Figure 7.

The photograph of Sungnyemun during the firefighting (Source: Cultural Heritage Administration and author edited) [38].

Figure 8.

The photograph of Sungnyemun after its fire (Source: Cultural Heritage Administration and author edited) [38].

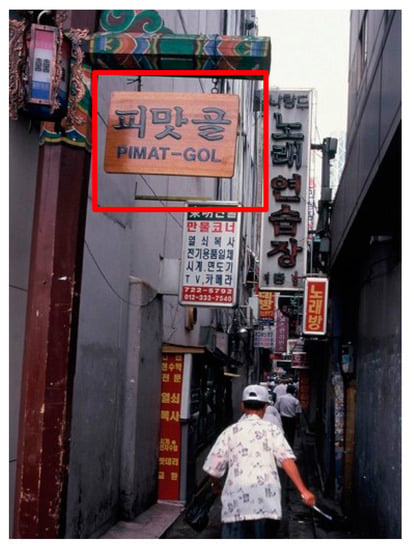

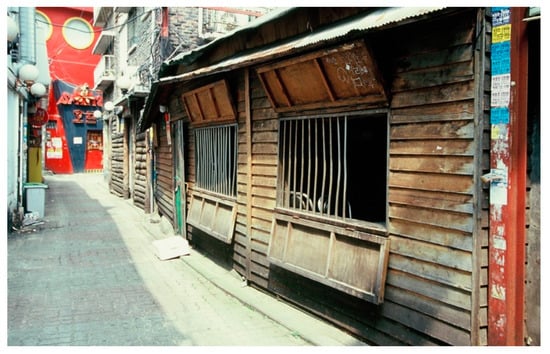

Speculating about Sungnyemun in relationship with its counterpart, for example myriad mundane city fabrics, is also critical in thinking the broader range of affectivities of heritage. What is less discussed in the Sungnyemun incident is another almost simultaneous urban project: the redevelopment of the pimatgol area (피맛골 in Korean) that is not far from where the gate is located (Figure 9 and Figure 10). Those two sites are separated by about ten minutes of driving time, the latter (pimatgol) being located towards the north, which is nearer Gwanghwamun Square and Gyeongbokgung Palace. Pimatgol is the second-order alley displaced alongside the main street (called Jongno) that was used for courtly parade during the Joseon Dynasty. It formed the horizontal axis of the medieval Seoul, which cuts across through a vertical axis coming from the Palace down to Sungnyemun. Pimatgol has existed for more than six centuries since the birth of the Dynasty, which is almost the same as Sungnyemun and other large-scale historic sites. However, what occurred is its massive demolition for urban redevelopment, which was executed under the administration of the former city mayor Lee Myung-bak (2008–2013), once the CEO of Hyundai Engineering and Construction, who had the nickname “bulldozer”. This is not a preservationist claim about the city that is doomed to disappear; instead, we aim to read the contrasting attitudes between those two heritages, which seem based on the criteria administered by certain agents such as governments and preservationists. Then, why would one be sympathetic with the disappearance of Sungnyemun that is rarely paid attention to in daily life despite its administrative emphasis, while a more widely-used everyday space such as pimatgol is simply dismissed in public debates? Instead of raising a moralistic point of view, we claim that the unusual attention given to the national monument’s extinction unfolds a complexity that is entangled with the strata of the everyday world, which is, however, not so much stabilized but rather latent to extend into new kinds of affectivity and discourse. The demolition of Sungnyemun was a tragic event, but its extensions opened up new ways of seeing that are neither grounded in its originality nor fully managed by any single agent from outside the heritage-scene. It is thus a prime example encouraging us to explore heritage as an open-ended field where multiple agents and stakeholders are comingled together and bring forth new ideas and affects, from which its conception is constantly renewed and thus becomes public in a fluid sense.

Figure 9.

The photograph of Pimatgol before the development (Source: The Seoul Research Data Service and author edited) [20].

Figure 10.

The photograph of Pimatgol before the development (Source: The Seoul Research Data Service and author edited) [20].

Meanwhile, it is worth noting that a Korea-based architectural journal entitled Architectural Critics Association (ACA) released a special issue dealing with the recent fire of Notre-Dame Cathedral (on 19 April 2019) and the Sungnyemun case. The issue includes twelve short essays, including the one by the chief editor Lee Jong-geun, who points out that the Sungnyemun restoration was the result of a short-sighted adherence to originality back to its initial settings. Referring to how the damaged Notre-Dame will presumably change through open competitions, also reminding how Eugène Viollet-le-Duc restored the cathedral in resilient ways that are not confined to archeological objectivity, Lee reads the Sungnyemun case as a chronic symptom reflecting the closedness of the Korean society in an intellectual sense [39]. Essays following the editorial are mostly critical in a similar vein, and, in the same way that the previous literature review addresses, propose to take the arson as a moment to rethink the heritage from various perspectives. Those authors aspire to take the case as an opportunity to think otherwise for other heritage sites in better ways. Most of them seem to agree with Viollet-le-Duc’s idea that “heritage is war” in a metaphoric sense that dealing with heritage inevitably entails interventions and reestablishments either conceptually or materially [40]. Related to this idea of heritage, Aron Vinegar argues that Viollet-le-Duc is incorrectly known as a “structural rationalist” despite the subtlety that his restoration is fused with “fact” and “fantasy”, both of which are not separated in a clear-cut manner [41]. Instead, Vinegar explains that Violllet-le-Duc’s childhood exposure to Notre-Dame was vital in conducting the restoration project. Such an exposure remained vague and mostly sensorially driven, such as light penetrating through a rose window and noises of the crowd, but led him to bring forth a proposal that structurally makes sense. That Viollet-le-Duc’s 19th-century restoration partly derived from his private memories and senses thus implies that restoring a heritage such as Notre-Dame before the fire would not necessarily mean to restore the absolute originality back to the present. What is established instead is an assemblage in which multiple origins and meanings are displaced in a rather symmetrical way. Could this seemingly radical but democratic way of thinking about heritage not be a guideline with which to work on the Sungnyemun restoration?

5. Conclusions

Although reading heritage through ANT is not completely new in itself given its widespread impacts, we claim that what makes Sungnyemun a relevant case of an actor-networked field as entangled with the post-disaster moods is evidenced at least by the following four aspects: (1) the porosity and incompleteness of heritage administration that could easily provoke public debates; (2) a nationalist sentiment that is not unrelated to Korea’s colonial and postcolonial past and beyond; (3) the impermanence of heritage caused by its fragile materiality (i.e., wood); and (4) the speed and intensity of social networking services generating senses of community in both online and offline spaces. All these four aspects are complexly interrelated, and what unfolds is an idea that reconsiders Sungnyemun from tabula rasa, although the reality is that this incident has almost ended after a loose provisional agreement among the related administrators and professionals that its rigorous technical reconstruction would resolve the debates that unfolded around the supposedly “number one” heritage in Korea. By revisiting what had happened around the incident, not just tracing back its material reconstruction processes but instead excavating a set of debates and issues which might have actually changed its public meanings in new ways, we argue that the 2008 arson is not so much a historical past as a vibrant issue that could still be actualized according to ideas and affects that might be derived from multiple spatiotemporal dimensions. By the same token, David Brett also claims that “history … is not a fixed entity but an activity” [42]. Our case study elicits how one is able to mediate a heritage such as Sungnyemun not preoccupied with its normative values, instead highlighting how its changing forms may mean to us in the present time and also bring forth an affective community in both online and offline spaces. Sungnyemun has stood in its original place for centuries but its values were not clearly identified. It was designated as a treasure during the Japanese colonial period and lifted up into a national treasure after independence. It has stood as an island in the midst of busy urban environments and played as a monument that citizens most often indifferently pass along. However, the unexpected fire prompted intense interests in Sungnyemun, which proved that the qualification of the supposedly much venerated heritage is suddenly put into question. In other words, the 2008 incident was a tragic event but also brought forth public discourses from which people began speculating its meanings from variously inauthentic perspectives. However, speculating the meaning of heritage, as several aforementioned scholars address, inevitably starts from here and now instead of its absolute origin back in history. Employing ANT is not an immediately applicable theory but rather a radical claim that Sungnyemun’s authenticity needs to be ever-generated from the present conditions, which would need to consider a number of issues such as post-colonial, post-disaster, compressed modernity, and the ethics of the post-Internet all of which influence the way that we conceive the heritage as part of daily life. Just as restoration is always a destructive process, rethinking the values of heritage is likewise an activity that inevitably accompanies tensions and dissents. Sungnyemun would have stood as it was for centuries without any meaningful investments into it unless the unexpected fire occurred, although the restored gate seems to fade into dismissal again. Last, while this article focuses on reading a single case in great detail, its implications are broad and applicable to other cases within and beyond the country. Analyzing the redesigning plan of Gwanghwamun Square is one possible topic, and rethinking the Notre-Dame fire as an instance of affective atmosphere or cosmopolitanism prompting a coming community is another. Either case would encourage us to perennially redefine what heritage means in changing worlds, and we wish that our study would open up new ways of making relationships with the environments that are still materially grounded but deeply mediatized.

Author Contributions

Both authors closely worked together from beginning to end, but took slightly different roles. The article originally started from D.W.A.’s long-term historical research on Sungnyemun and later expanded through the collaboration with S.P. who redesigned it through the employment of theory. The empirical research on Sungnyemun in Section 2, Section 3 and Section 4 is the result of D.W.A.’s contribution, whereas S.P. focused on interpreting the case in consultation with ANT, heritage studies, and issues of the post-disaster in an international context. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2017R1D1A1B03028056).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jung Gu of Seoul. A Precision Survey Report of Sungnyemun Gate; Jung Gu of Seoul: Seoul, Korea, 2006; Available online: http://www.cha.go.kr/cop/bbs/selectBoardArticle.do?nttId=1694&bbsId=BBSMSTR_1021&pageIndex=4&pageUnit=10&searchCnd=tc&searchWrd=%ec%88%ad%eb%a1%80%eb%ac%b8&ctgryLrcls=&ctgryMdcls=&ctgrySmcls=&ntcStartDt=&ntcEndDt=&searchUseYn=Y&mn=NS_03_08_01 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA). A Repair Report for the Construction of Sungnyemun Restoration and the Castle Restoration; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2013. Available online: http://www.cha.go.kr/cop/bbs/selectBoardArticle.do?nttId=27969&bbsId=BBSMSTR_1021&pageIndex=1&pageUnit=10&searchCnd=tc&searchWrd=%ec%88%ad%eb%a1%80%eb%ac%b8&ctgryLrcls=&ctgryMdcls=&ctgrySmcls=&ntcStartDt=&ntcEndDt=&searchUseYn=Y&mn=NS_03_08_01 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Rii, H.-U.; Choi, J.-H. Sungnyemun: Spiritual meaning for Koreans. In The 2008 ICOMOS Conference Paper; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/quebec2008/ (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). The Nara Document on Authenticity 1994. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Anderson, B.; Holden, A. Affective Urbanism and the Event of Hope. Space Cult. 2008, 11, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeleński, T. Practices of Built Heritage Post-Disaster Reconstruction for Resilient Cities. Buildings 2018, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klekot, E. Constructing a ‘monument of national history and culture’ in Poland: The case of the Royal Castle in Warsaw. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, T. Reclaiming Post-disaster Narratives of Loss in Indonesia. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.; Conradson, D. Transitional Organisations, Affective Atmospheres and New Forms of Being-in-common: Post-disaster Recovery in Christchurch, New Zealand. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2018, 43, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, C. Rethinking Architectural Heritage Conservation in Post-disaster Context. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Principles for the Preservation of Historic Timber Structures October 1999. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Latour, B. Pandora’s Hope; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, J. Whose Place Is This Anyway? An Actor-Network Theory Exploration of a Conservation Conflict. Space Cult. 2018, 21, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmo, R. Actor-Network Theory and Methodology: Social Research in a More-than-human World. Methodol. Innov. Online 2011, 6, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.-J. Assembling the Historic City: Actor Networks, Heritage Mediation, and the Return of the Colonial Past in Post-Soviet Cuba. Anthropol. Q. 2018, 91, 1235–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Aramis, or, the Love of Technology; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, C. Rethinking (In)tangible Heritage: Social Constructionism and Actor-Network Theory Approaches. In XVIII ISA—Facing and Unequal World, Challenges for Global Sociology, Yokohama, Japan; International Sociological Association: Madrid, Spain, 2014; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. On Heritage Ontologies: Rethinking the Material Worlds of Heritage. Anthropol. Q. 2018, 91, 1365–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Seoul Research Data Service. Available online: http://data.si.re.kr/psearch (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- National Institute of Korean Language. Korean-Foreign Language Learners’ Dictionary. Available online: https://stdict.korean.go.kr/main/main.do#main_logo_id (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Korea Ministry of Government Legislation. Cultural Heritage Protection Act 25 March 2015. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=33988&lang=ENG (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA). Bringing the Spirit of Sungnyemun; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2013.

- The Colonial Joseon Government General. The 1933 Preservation Policy of Treasure, Relics, Scenic Beauty, Natural Monument in Joseon. Available online: https://www.museum.go.kr/modern-history (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA). Cultural Heritage Protection Act 2012. Available online: http://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=26478&lang=ENG/ (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Lee, D.-K. A Restoration Corruption of Gwanghwamun and Sungnyemun. Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation (26 March 2014). Available online: https://news.v.daum.net/v/20140326132707762?f=o (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Kim, T.-G.; Park, H.-M. Continual Sufferings of Sungnyemun. NEWSIS 8 November 2013. Available online: http://www.newsis.com (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage October 1999. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Principles for the Conservation of Wooden Built Heritage October 1999. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage (2003). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/structures_e.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Roh, H.-S. The Limit of Sungnyemun Restoration and the Absence of Preservation Philosophy. In Presentation Paper for the 2017 Korean Association for Architectural History; Korea Association for Architectural History: Seoul, Korea, 2017; pp. 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Cuc, C. On the Meaning of Heritage in South Korea. Studia UBB Philol. 2013, 58, 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. We Have Never Been Modern; trans. Catherine Porter; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- An, D.-W. Characteristics and Utility of 3D Scandata for the Development of Survey Drawings in Wooden Architectural Heritage: A Comparison of the Raw Survey Data Used in Survey Drawings. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2016, 15, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA). A Survey Report of Sungnyemun’s Control Elements Caused by Fire; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2009.

- Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA). A Report of Sungnyemun’s 3D-restorative Process Report; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2012.

- Musil, R. Monuments. In Posthumous Papers of a Living Author; Peter Wortsman, trans./Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA). A Report for the fire Damage of Sungnyemun; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2008. Available online: http://www.cha.go.kr/cop/bbs/selectBoardArticle.do?nttId=21298&bbsId=BBSMSTR_1021&pageIndex=4&pageUnit=10&searchCnd=tc&searchWrd=%ec%88%ad%eb%a1%80%eb%ac%b8&ctgryLrcls=&ctgryMdcls=&ctgrySmcls=&ntcStartDt=&ntcEndDt=&searchUseYn=Y&mn=NS_03_08_01 (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Lee, J.-G. Notre-Dame Cathedral and Our Portrait. Archit. Crit. Assoc. 2019, 18, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Vinegar, A. Chatography. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 2012, 71, 362–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinegar, A. Viollet-le-Duc and Restoration in the Future Anterior. Future Anterior 2006, 3, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bratt, D. The Construction of Heritage; Cork University Press: Cork, Ireland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).