1. Introduction

Educational effectiveness research is essential for any country because of the impact its results can have on decision-making in its education system [

1,

2]. In this way, the research provides interesting findings on the aspects of the classroom and the school that contribute to student development and learning.

Teaching effectiveness research studies the factors that promote student learning and define the quality of teachers. The classroom is constituted in this research as the main space in which learning takes place, where the elements must be to achieve effective learning [

3,

4]. Teachers who manage to get their students to learn more include a variety of didactic resources in their teaching. This is why it is necessary to identify their application of the learning processes [

5].

Technological resources are clearly an element that provides benefits in the teaching of secondary education, according to different studies [

6,

7,

8]. These improvements take place thanks to the role of technology as a facilitator of communication and interaction between the learner and the information. Studies [

9,

10] also emphasize this idea and suggest the interactivity of technological resources as a means of promoting more meaningful and deeper learning. However, there is an uneven use of technologies in and out of school. The element that limits the positive effects mentioned above is the difficulty in standardizing their use in the classroom. Therefore, the main aim of this paper is to study the correlation between the use of mobile phones and the academic performance of high school students.

2. Materials and Methods

This research’s main objectives were to understand the impact that the use of mobile phones in educational centers produces in the academic performance of high school students, and in turn, if this academic performance is affected by the use of cloud services.

To respond to these objectives, we carried out a secondary exploitation of the database of the Ministry of Education of Spain corresponding to 2017. The Ministry of Education issues periodic reports through the National Institute of Statistics, which publishes different educational parameters on its institutional website that aim to contextualize the country’s educational panorama. In order to elaborate on these reports, the data collected by the educational centers in their performance tests, as well as in the questionnaires by the management teams from the schools, were used.

This research worked with the data on the technological resources of educational centers and with the data of school performance.

The variables used were of two types: independent variables and dependent variables.

The independent variables used were: schools using mobile phones (mobile_centr) and schools with cloud services (cloud_ centr).

The dependent variables used were: student bodies graduating from compulsory secondary education (CSE), called (grad_ stud), repeat students in CSE (repet_stud), student bodies in CSE using the cloud service, and student families using the cloud service (cloud_fam).

The CSE, as its name suggests, is compulsory in Spain. It covers an average student between 12–16 years of age (if not repeated). This stage is divided into four courses. After finishing it, an academic degree is obtained.

The data was collected anonymously. At the same time, it is worth mentioning that:

“For the achievement of this state statistic, active cooperation was established between the Ministry of Education and the educational administrations of the Autonomous Communities through the Statistical Commission of the Conference of Education. The Technical Group for Statistical Coordination, made up of representatives from the statistical services of the Ministry and the Autonomous Communities, reports to said Commission.”

The sample was made up of 1,887,027 students in secondary education registered at that time in any of the educational centers in Spain, and the 7381 secondary schools, as you can see in

Table 1. It was understood as registered students who were taking at least one subject in this educational stage. The information was collected from students’ academic results derived from the final evaluations (in the months of June/September).

All the information in the statistics—except student results—corresponded to the situation of the school year in the middle of October, when the educational activity of the year was fully operational.

The sample was composed of 968,079 (51.31%) male students and 918,948 (48.69%) female students. The rest of the variables are described in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

Each subject in the sample participated in the following categories:

- −

The CSE center to which it belonged.

- −

If the center allowed the use of the mobile phones for educational purposes.

- −

If the center used cloud services.

- −

If the student used cloud services.

- −

If the student graduated.

- −

If the student repeated a course.

- −

If the family used cloud resources.

We describe what is meant by each of the sections considered in the study:

Compulsory secondary education center: anyone who teaches this stage of education can also teach other stages, which was not considered in this study.

Cloud service: a service mainly for data or information storage, either in the form of documents, programs, files, or photos, etc. It was considered whether the center had this service or not. It was considered whether the student used the cloud when using its services from his educational center.

This included whether or not students were allowed to use their mobile phones for educational purposes in the center. Therefore, if the center allowed its use, this was noted.

Students were considered to have graduated when they finished CSE with a pertinent academic degree. A repeat student was considered to be one who had enrolled in the higher course he was attending, in which, he was already enrolled. A student who was enrolling for the first time in a full academic year and had subjects pending was not considered a repeater. Families were considered to be using the cloud services when they used the cloud service of the educational center where their child/children are enrolled.

3. Results

A set of information was available with the educational variables chosen: centers that allowed the use of mobile phones (mobile_centr), students who graduated (grad_ stud), students who repeated (repet_stud), centers with cloud services (cloud_ centr), and families with cloud services (cloud_fam). The values of these variables were distributed among the different Autonomous Communities (17+2). We first confirmed the normality of the data offered by the Ministry, applying the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk test and taking the latest one (

Table 4) [

33].

To determine the dependence of the variables and to discover the correlation that the use of mobiles in schools could have with the different variables analyzed, as well as the significance of these relationships, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was applied.

Table 5 shows high correlations among:

Centers that used mobile phones and students that graduated.

Schools using mobile phones and students repeating.

There were moderate correlations between:

Families with cloud services and students who graduated.

Families with cloud services and repeaters.

In contrast, there was no significant correlation between:

Centers with cloud services and graduate students.

Centers with cloud services and students who repeated.

As in our model, the interest was focused on the relationship with variables that handled the use of mobile phones. We found high correlations with both students who graduated (higher) and students who repeated (high, but slightly lower).

We sought the linear regression model, which explains the relationship between these variables, understanding the use of mobile phones in the center as a predictor variable and the dependent variable was both students who promoted and students who repeated. The model obtained was direct for the students who graduated with an R2 = 0.617, and inverse with an R2 = −0.527 for students who repeated.

After analyzing

Table 5, which represents the mobile_centr variable, and being certain of its correlation with the grad_ stud and repet_stud, we looked for a critical value that offered us significant differences, with respect to both, and that explained more than 95% of the model.

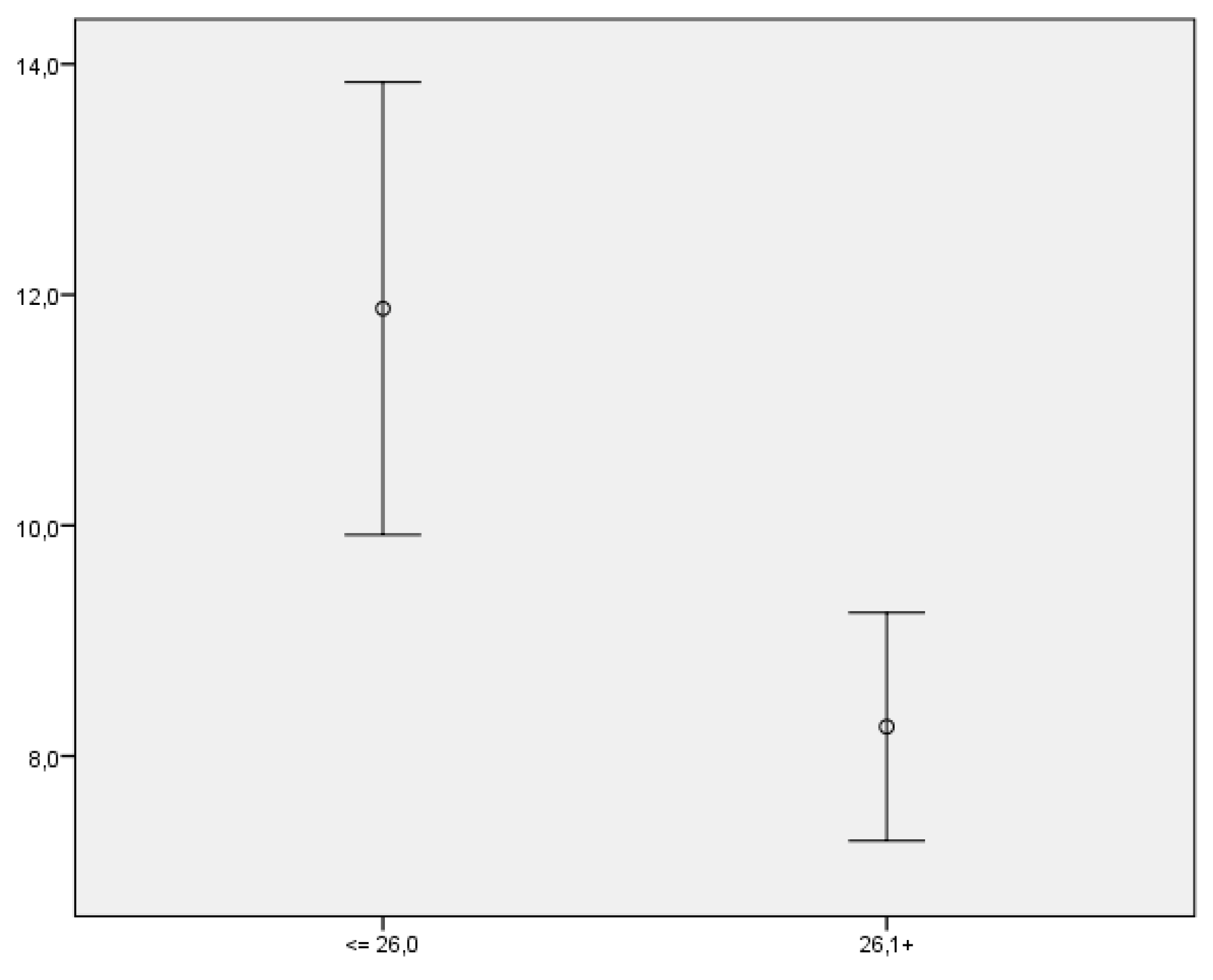

After observing the possible key points of the graph and testing with different values, we opted for 0.26 as the value of mobile_centr that offered us just what we sought. Thus, we divided the variable into two intervals from that value, and we obtained positive data, which is shown in

Table 6.

Up to 26% of centers allowed the use of mobile phones, and the approval rate was 64%. With more than 26%, the approval rate rose to 76%.

As shown in

Figure 1, the variables did not overlap, and, therefore, it was the point of the variable that had a sensitive effect on the passed ones.

As a result, the Independent Samples t Test could be done for the equality of means, and we obtained the expected significance for that point, as shown in

Table 7.

4. Discussion

Although there is sufficient literature on the effects of online learning systems on students’ learning and satisfaction [

34,

35,

36], scant literature exists that explores the effect of using smartphones to learn.

This research seeks to provide answers regarding the objectives proposed on the use of mobile phones and, therefore, has opted to analyze the correlation between the use of mobile phones in schools and the percentage of students who graduate, obtaining a result of 0.786 and an R

2 of 0.617, which confirms the high correlation and positive linear regression—that is, the use of smartphones in educational centers is associated with better academic results for the students. This idea is in line with other studies with similar themes [

37,

38,

39,

40], which have found positive effects of the use of mobile devices compared to those students who learn in traditional classrooms, or even those who only use the PC’s in the classroom. As mobile phones have also become the main communication device, students who use a smartphone more frequently to learn are more likely to perceive and experience this positive impact on their academic performance [

37,

41].

This study also addresses the issue of students with poorer academic results and those who repeat. The data obtained showed a reduction in the number of repeaters with a higher percentage of educational centers allowing the use of mobile phones. This reduction of repeaters occurred significantly, with a result of −0.726 and 0.527 regarding correlation and R2. Moreover, when the number of centers that allow mobile phones was below 26% of the total population, the rate of repeaters rose to 11.88%. Indeed, when the number of centers rose to more than 26%, the number of repeaters was significantly reduced to 8.2%. As a consequence, we can see a positive effect of this technology on the performance of students with lower academic results, reducing the percentage of school failure.

However, the researchers show that the use of smartphones does not reduce school failure [

42], given that it not only depends on the use of smartphones in schools, but also on many different variables to reduce this problem [

37,

43,

44].

This research obtained results that showed an improvement in academic performance associated with the use of mobile phones in schools (

Table 5), with a breakpoint of 0.26, which explains how, when less than 26% of secondary education centers allowed the use of mobile phones in class, the rate of graduates was 64%, increasing to 76% when it was higher than 26%.

Unfortunately, not all studies are so robust. Some recent studies [

45] have found no statistically significant differences between students who used smartphones and those who learned with printed materials. Even some studies in higher education [

46] show that despite the use of mobile phones for learning, there is a weak inverse correlation between the use of these tools and academic grade point average (GPA). As a consequence, mobile phone use in the classroom not only fails to improve results, but also makes them worse in some cases. Smartphones are often depicted as having a negative effect on the academic performance of higher education students even though they are used for learning activities. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate and understand the use of smartphones among students and take into account the age and maturity of the students, since in secondary and higher education, the results are different.

The way that mobile phones are used seems to be more important than the use itself. If information is transmitted essentially in one direction, then the influence in terms of grades could be null or negative [

46]. Some studies indicate that searching for and solving information with these devices on the Internet is associated with better student grades [

47]. These statements may seem to clash with the data obtained by the Ministry of Education, given that an increased use of mobile devices in schools improves academic results (

Table 4), but there really is no such discrepancy, considering that it is essential to take into account the way that mobile phones are used in schools.

Researchers confirm that the students who are more digitally competent obtain better academic grades [

48,

49,

50,

51]. This can also influence the perception of handsets, as university students with greater self-efficacy in using mobile phones are more likely to perceive the positive effect in their academic performance [

52].

A recent study [

52] introduces a model to address the use of smartphones for the learning of university students. It shows how important it is to familiarize students with educational communication with mobile phones before introducing them into learning. Increasing this familiarity impacts academic performance. Researchers warn that this familiarity and the excessive use of mobile phones, without proper supervision, can lead to addiction problems [

53,

54].

Unlike the use of mobile devices, we have the example of cloud services. The statistical analysis showed that there are no significant results, both in terms of correlation and significance, with 0.032 and 0.896 respectively. This coincides with previous studies [

55] that have highlighted the differences in the beliefs presented by students and teachers regarding efficiency as an educational methodology. It is likely that this is a result of using the cloud as a simple store and not taking advantage of the multiple functionalities the service has. Despite the fact that student motivation is high, this does not translate into good academic results, particularly as the use of this service cannot be extrapolated to improve the results because this depends on multiple variables [

56,

57].

In light of the findings, we decided not to look any further into the influence of cloud services on academic results.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusion we reach is that in schools where mobile phone use is allowed, there is a positive impact on academic performance. This improvement is seen unanimously in the scientific community; the different elements that accompany the use of mobile phones in the center determine this possible improvement. In other words, the mobile phone itself does not offer the improvement, but, rather, it depends on various factors, such as the way the device is used, the type of activity carried out, and the age or maturity of the student. For all these reasons, it is advisable to continue to study the subject in depth to clarify the elements that accompany the use of mobile phones and to design learning experiences that integrate appropriate teaching methodologies. This must necessarily be accompanied by suitable teacher training with programs that integrate digital competency learning into educational programs, both in the training of future teachers and in their ongoing training [

58]. With all of this, it can be said that the first objective proposed in the research has been achieved.

The second conclusion concerns students with lower academic qualifications, who seem to be particularly affected by the incorporation of mobile phones into the teaching process. These students notice significant improvements in their assessment, to the extent that they significantly reduce the number of repeaters in schools that allow the use of mobile devices. This is where studies agree on the increased interest and motivation caused by the use of mobile phones [

28], as most of the students who repeat suffer from a special lack of motivation for studying, and when this is improved, academic results rise at the same time.

The third conclusion is linked to cloud services, which are accessed by smartphones and other technological devices. Education authorities have made a huge effort to ensure that many schools in the country have the services (digital platforms, networked hard drives) that are considered less suspicious than other technologies, such as social networks or mobile phones. Contrary to what we might have expected, the availability of these services is not accompanied by any improvement in academic performance. They seem to have little influence on academic performance. Again, the reason can be found in their use, mostly to store and share documents and information, and not taking full advantage of their potential. Looking at the relationship between academic performance and the use of cloud services, it can be concluded that academic performance is not influenced by this variable. It can, therefore, be said that the second objective of the research has been achieved.

In light of the results and after considering the conclusions, we can say that the question raised in the introduction of this article has been answered. We can say that there is a strong correlation between the use of mobile phones and academic performance, so it can be inferred that they are an element that improves it in a positive way.

The limitations of the study were determined by the fact that it is a secondary exploitation of a database. This led to a study on whether the use of smartphones affected the academic performance of average students in secondary education. For future research, variables will be taken into account, such as the use of this tool by the teacher, differences between public or private centers, the socio-economic level of the students, and disciplines, among others. This will help to define and delimit future studies.