Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Definition of Telework

2.2. Factors that Affect Telework

2.2.1. Technological Factors

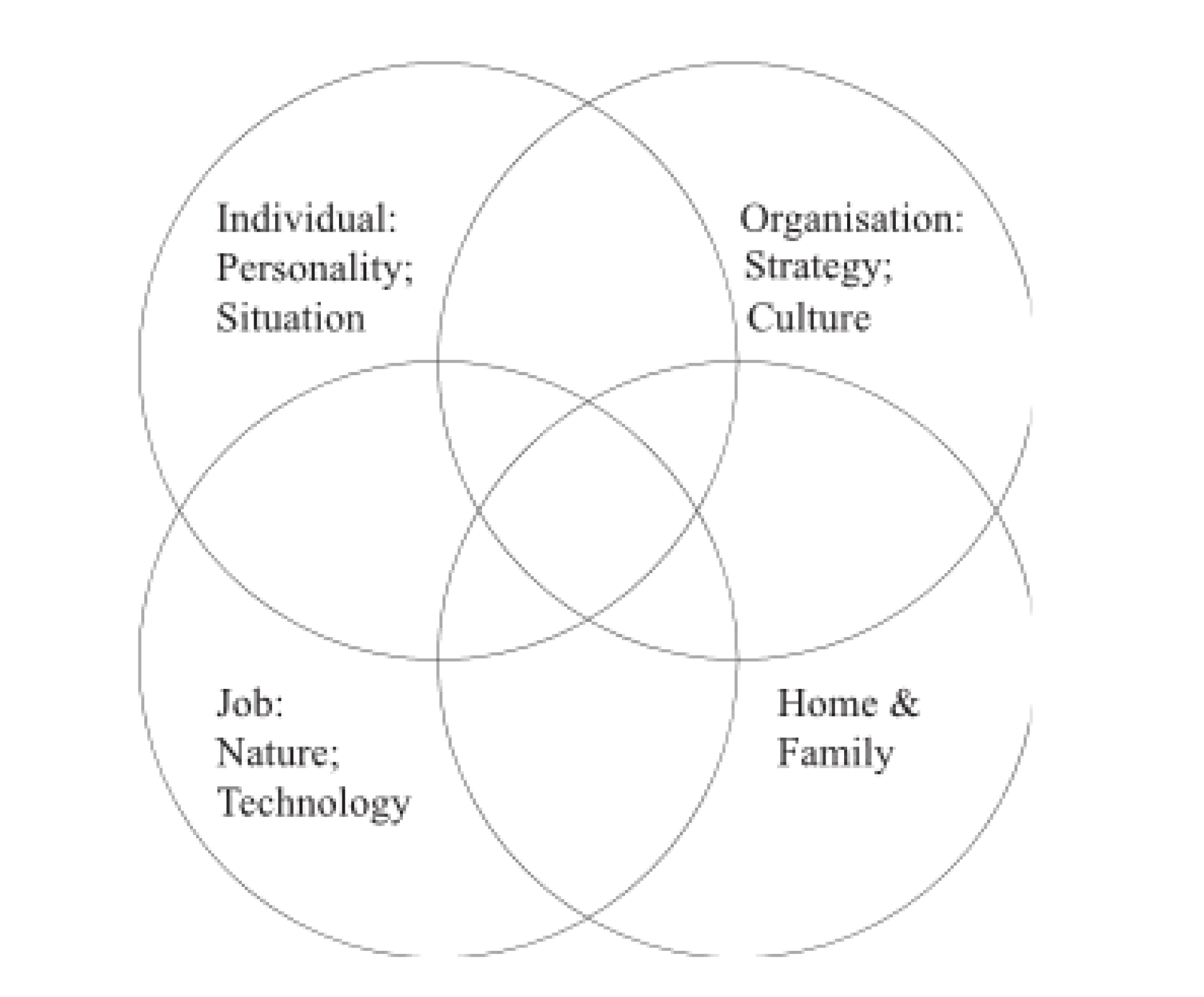

2.2.2. Individual, Organization, and Home-Family Factors

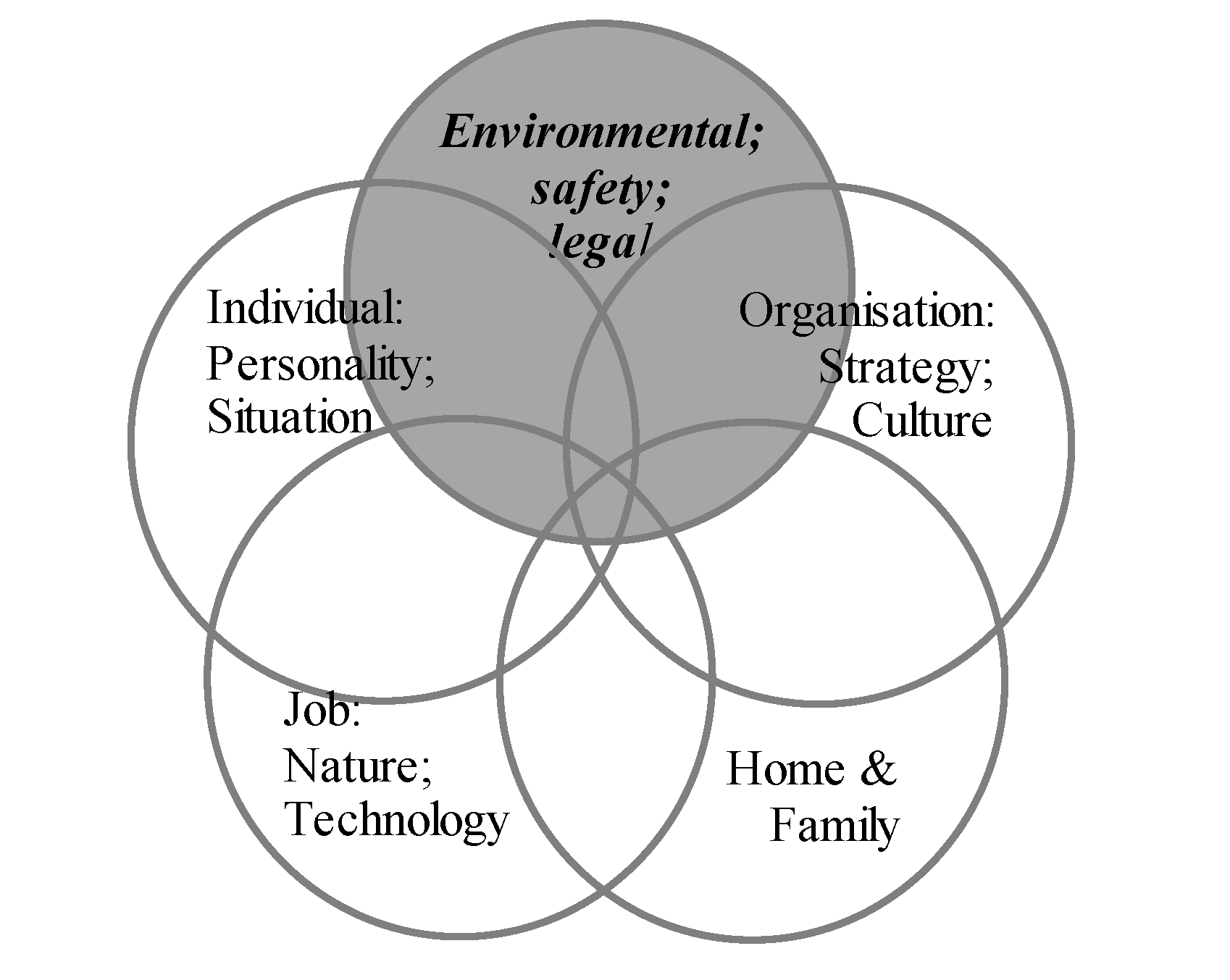

2.2.3. Environmental, Safety, and Legal Factors

3. Materials and Methods

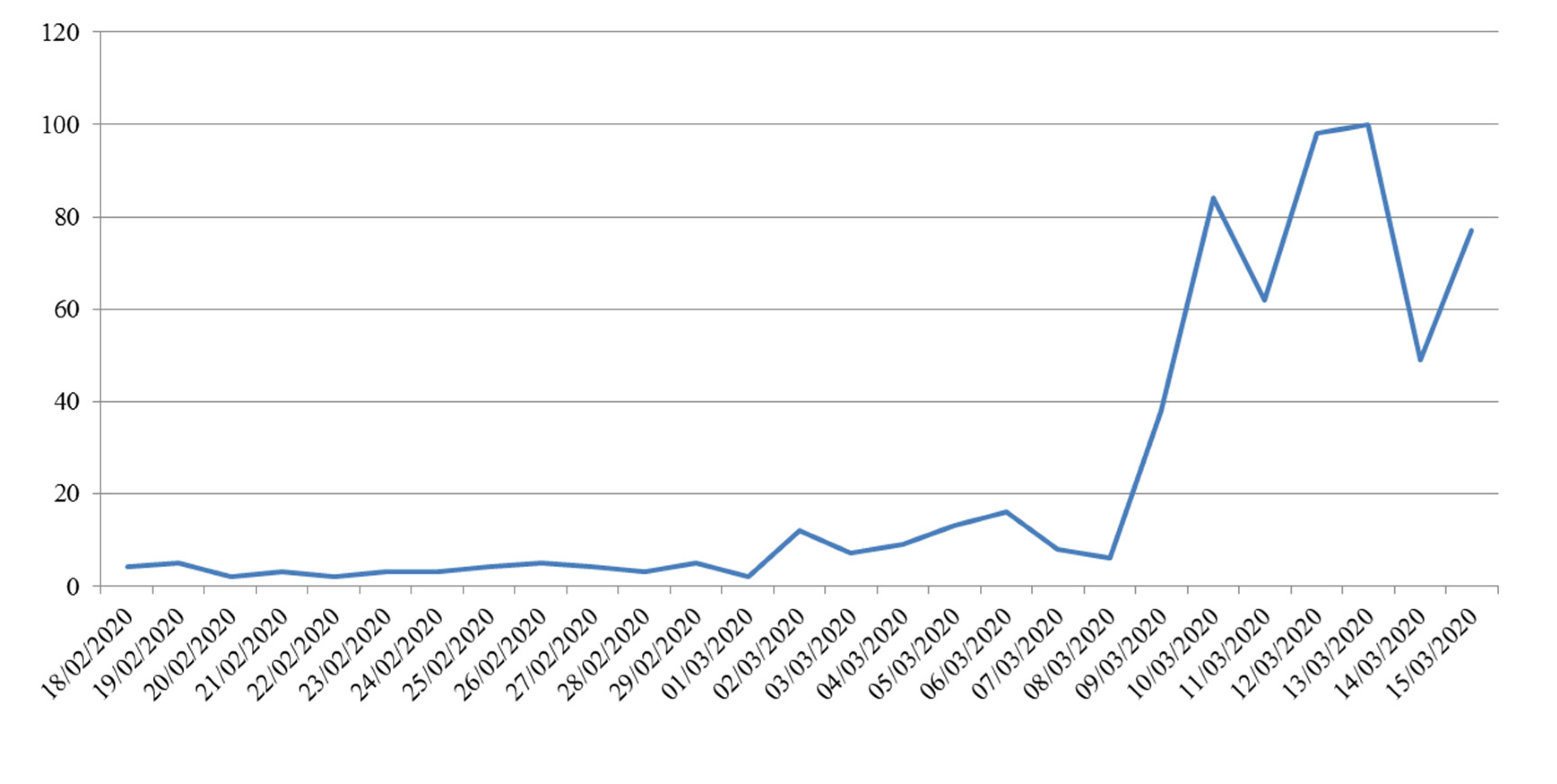

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baruch, Y.; Nicholson, N. Home, Sweet Work: Requirements for Effective Home Working. J. Gen. Manag. 1997, 23, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.; Bleijenberg, I.; Oldenkamp, E. The Telework Adoption Process in a Dutchand French Subsidiary of the Same ICT-Multinational: How National Culture and Management Principles Affect the Success of Telework Programs. J. E-Work. 2009, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiléra, A.; Lethiais, V.; Rallet, A.; Proulhac, L. Home-based telework in France: Characteristics, barriers and perspectives. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 92, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound and the International Labour Organization. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Tavares, A.I. Telework and Health Effects Review, and a Research Framework Proposal; Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/71648/1/MPRA_paper_71648.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Baruch, Y. Teleworking: Benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New Technol. Work Employ. 2000, 15, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, J. Telecommunications and Organizational Decentralization. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1975, 23, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A.; Pastor-Gosálbez, M.I. Telework as a Driver of the Third Sector and its Networks. In Social E-Enterprise: Value Creation through ICT; Torres-Coronas, T., Vidal-Blasco, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.E.; Kurland, N.B. A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H. Future of Work and Flexible Working in Estonia: The Case of Employee-Friendly Flexibility; Arenguseire Keskus: Tallinn, Estonia, 2018; Available online: http://www.wafproject.org (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- ILO. Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work (Research Report); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017.

- Messenger, J.C.; Gschwind, L. Three generations of Telework: New ICTs and the (R)evolution from Home Office to Virtual Office. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2016, 31, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J.; Ferris, M.; Märtinson, V. Does it matter where you work? A comparison of how three work venues (traditional office, virtual office, and home office) influence aspects of work and personal/family life. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.H.; Pearlson, K. Two cheers for the virtual office. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1998, 39, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- López-Feal, R. Mundialización y Perfiles Profesionales; Horsori Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sener, I.N.; Bhat, C.R. A Copula-Based Sample Selection Model of Telecommuting Choice and Frequency. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2011, 43, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, M.; Safirova, E.; Jiang, Y. What Drives Telecommuting? The Relative Impact of Worker Demographics, Employer Characteristics, and Job Types. J. Transp. Res. Board 2007, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, M. Determinants of Work-at-Home Arrangements for German Employees. Labour 2015, 29, 444–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareis, K.; Hüsing, T.; Mentrup, A. What Drives eWork? An Exploration into Determinants of eWork Uptake in Europe. In Proceedings of the 9th International Telework Workshop, Heraklion, Greece, 6–9 September 2004; pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Overbey, J.A. Telecommuter intent to leave. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 680–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, M.; Gomez-Mejia, L.; Firfiray, S.; Berrone, P.; Villena, V.H. Leader beliefs and CSR for employees: The case of telework provision. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 609–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautsch, B.A.; Kossek, E.E.; Eaton, S.C. Supervisory approaches and paradoxes in managing telecommuting implementation. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 795–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.M.; Țuclea, C.-E.; Vrânceanu, D.-M.; Ţigu, G. Sustainable Social and Individual Implications of Telework: A New Insight into the Romanian Labor Market. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulin, E.; Vilhelmson, B.; Johansson, M. New Telework, Time Pressure, and Time Use Control in Everyday Life. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hraskova, D.; Rolkova, M. Teleworking, a Flexible Conception of Managing the Enterprise. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Scientific Conference “Whither Our Economies”, Mykolas Romeris University, Vilnius, Lithuania, 15–16 October 2012; Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/42526/1/MPRA_paper#page=40 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A. El control del tiempo de trabajo en el teletrabajo itinerante. Sociol. Del Trab. 2002, 45, 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ruth, S.; Chaudhry, I. Telework: A Productivity Paradox? IEEE Int. Comput. 2008, 12, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagut, W.V.; Carrillo, L.P.V.; Delgado, M.D.P.S. Model for implementation of teleworking in software development organizations. Sistemas Telemática 2017, 15, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lier, T.; De Witte, A.; Macharis, C. The Impact of Telework on Transport Externalities: The Case of Brussels Capital Region. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 54, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, F. Gaining the Air Quality and Climate Benefit from Telework. Environmental Protection Agency and the AT&T Foundation. 2004. Available online: http://pdf.wri.org/teleworkguide.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Ursery, S. Austin fights air pollution with telework program. Am. City Cty. 2003, 118, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, T.P.; Andersen, S.K. A New Mode of European Regulation? The Implementation of the Autonomous Framework Agreement on Telework in Five Countries. Eur. J. Ind. Relat. 2007, 13, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyöriä, P. Managing telework: Risks, fears and rules. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, T. The implementation of the Telework and Work-related Stress Agreements: European social dialogue through ‘soft’ law? Eur. J. Ind. Relat. 2011, 17, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, N.; Proctor-Thomson, S.B. Disrupted work: Home-based teleworking (HbTW) in the aftermath of a natural disaster. New Technol. Work Employ. 2015, 30, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D. Applying technology to work: Toward a better understanding of telework. Organ. Manag. J. 2009, 6, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity; Sage: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- King, G.; Verba, S.; Keohane, R.O. El Diseño de la Investigación social. La Inferencia Científica en los Estudios Cualitativos; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat (Statistical Office of the European Union). Internet Activities in the European Union. Statistics in Focus. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3433488/5572828/KS-NP-05-040-EN.PDF/3b83b8f4-1f03-48dd-ad1c-bc1169a3e2ba (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- OECD. How’s Life in the Digital Age?: Opportunities and Risks of the Digital Transformation for People’s Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.R.; Gilligan, M.J.; Golder, M. A Simple Multivariate Test for Asymmetric Hypotheses. Polit. Anal. 2006, 14, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE (National Statistics Institute). Encuesta De Población Activa. 2018. Available online: www.ine.es (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Adecco. Monitor Adecco Oportunidades Y Satisfacción En El Empleo. 2018. Available online: https://www.adeccogroup.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Monitor-Adecco-de-Oportunidades-y-Satisfacci%C3%B3n-en-el-Empleo.-II-trimestre-2018.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Allenby, B.R.; Richards, D. Telework and the triple bottom line. In Sustainable Solutions; Charter, M., Tischne, U., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, P. Teletrabajo y comercio electrónico. In Ministerio De Educación; Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sitles, J. Strategic niche management in transition pathways: Telework advocacy as groundwork for an incremental transformation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 34, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohalik, S.; Westerlund, M.; Rajala, R.; Timonen, H. Increasing the adoption of teleworking in the public sector. In Proceedings of the ISPIM Conference Proceedings, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 7–10 April 2019; Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/7b90fd7b719359d910b5ff9c1a9e6141/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1796422 (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Brown, C.; Smith, P.; Arduengo, N.; Taylor, M. Trusting telework in the federal government. Qual. Rep. 2016, 21, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Caillier, J.G. Do Teleworkers Possess Higher Levels of Public Service Motivation? Public Organ. Rev. 2015, 16, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcalla, M.A.; Belzunegui-Eraso, A. Marcos jurídicos y experiencias prácticas de teletrabajo. Aranzadi Soc. 2003, 5, 1333–1376. [Google Scholar]

- CEOE. Document of Proposals by the Trade Unions CCOO and UGT and the Entrepreneur Organizations CEOE and CEPYME to Address, by Extraordinary Measures, the Labor Problem Generated by the New Type of Coronavirus; CEOE: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://contenidos.ceoe.es/CEOE/var/pool/pdf/publications_docs-file-771-documento-de-propuestas-conjuntas-de-las-organizaciones-sindicales-ccoo-y-ugt-y-empresariales-ceoe-y-cepyme-para-abordar-mediante-medidas-extraordinarias-la-problematica-laboral-generada-por-la-incidencia-del-nuevo-tipo-de-c.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Myllyvirta, L. As China Battles One of the Most Serious Virus Epidemics of the Century, the Impacts on the Country’s Energy Demand and Emissions are Only Beginning to Be Felt; Carbon Brief Ltd.: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-coronavirus-has-temporarily-reduced-chinas-co2-emissions-by-a-quarter (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Rebmann, T.; Wang, J.; Swick, Z.; Reddick, D.; DelRosario, J.L. Business continuity and pandemic preparedness: US health care versus non-health care agencies. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2013, 41, e27–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, D.C.; Confield, E.; Gasner, M.R.; Weisfuse, I. A qualitative study of pandemic influenza preparedness among small and medium-sized businesses in New York City. J. Bus. Contin. Emerg. Plan. 2011, 5, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- ACOEM. Pandemic Influenza Guidance for Corporations. ACOEM Emergency Preparedness Task Force. 2010. Available online: https://stagesd.acoem.org/acoem/media/News-Library/Pandemic-Influenza-Guidance-for-Corporations.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Lurie, N.; Dausey, D.J.; Knighton, T.; Moore, M.; Zakowski, S.; Deyton, L. Community Planning for Pandemic Influenza: Lessons from the VA Health Care System. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2008, 2, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.; Dix, K.S. Pandemic Preparations for the Workplace. Colo. Lawyer 2009, 38, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

| Modality | Use of Technology | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Regular home-based telework | Always or almost all the time | From home at least several times a month and in other locations less often than several times a month. |

| High mobile telework | Always or almost all the time | At least several times a week in at least two locations other than the employer’s premises or working daily in at least one other location. |

| Occasional telework | Always or almost all the time | Less frequently and/or fewer locations than high T/ICTM |

| Company | Sector | Date | Employees Affected | Individual | Organisation | Job | Home & Family | Environmental, Safety & Legal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PeopleMatters | Human Resources consultancy | 09/03/2020 | All employees | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Social networks | 10/03/2020 | Voluntary (all employees) | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Bankia | Banking services | 06/03/2020 | Employees from a plant of the company | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Indra | Technological Company | 05/03/2020 | Two plants in Barcelona | ✓ | ||||

| EY | Consultancy | 05/03/2020 | 3300 employees in Madrid | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Cellnex | Telecommuting | 04/03/2020 | Employees located in the North of Italy | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Uniteco | Insurance services | 10/03/2020 | Employees with children in Madrid | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Iberdrola | Energy Company | 12/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ||||

| Endesa | Energy Company | 03/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ||||

| BBVA | Banking services | 11/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Ericsson | Technological Company | 08/03/2020 | Employees located in Croatia | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Technological Company | 08/03/2020 | 8000 employees in Ireland | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Repsol | Energy Company | 10/03/2020 | Employees located in Madrid | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gamesa | Renewable energy | 11/03/2020 | 400 employees located in Navarra | ✓ | ||||

| Banco Santander | Banking services | 12/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Vodafone | Telecommunications Company | 04/03/2020 | 2200 employees located in Spain | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Orange | Telecommunications Company | 11/03/2020 | 1400 employees located in Madrid | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| LG Electronics | Technological Company | 14/03/2020 | Employees located in Korea, Iran, USA, Italy, and Spain | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Microsoft | Technological Company | 14/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Axa | Insurance services | 14/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Ence | Cellulose manufacturing | 14/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Banco de España | Institution | 14/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ||||

| Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores | Institution | 14/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| El Corte Inglés | Retail Company | 03/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Caixabank | Banking services | 12/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ||||

| Ferrovial | Infrastructures | 11/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ||||

| Mapfre | Insurance services | 11/03/2020 | N/A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Collective Agreements Considerations | Before the Covid-19 Crisis | During the Covid-19 Crisis |

|---|---|---|

| Voluntary character | Yes | No |

| Individual agreement | Yes | No |

| Reversibility | Yes | No |

| Equality of rights between teleworkers and workers at the employers’ premises | Yes | Yes |

| Work equipment facilitation and installation | Yes | Software only |

| Ergonomic elements | Yes | No |

| Technical support | Yes | Yes |

| Costs of telework | If required | If required |

| Health, social security and job security | Yes | No |

| Right to union representation | Yes | Yes |

| In-company training | Yes | Yes |

| Preservation of economic conditions | Yes | Yes |

| Modifications in the statute of rights for workers | No | No |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093662

Belzunegui-Eraso A, Erro-Garcés A. Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability. 2020; 12(9):3662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093662

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelzunegui-Eraso, Angel, and Amaya Erro-Garcés. 2020. "Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis" Sustainability 12, no. 9: 3662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093662

APA StyleBelzunegui-Eraso, A., & Erro-Garcés, A. (2020). Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability, 12(9), 3662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093662