Contribution to the Analysis of Depopulation in Rural Areas of the Balkans: Case Study of the Municipality of Niksic, Montenegro

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Montenegro

2.2. Recent History

2.3. Population

2.4. The Municipality of Niksic

2.5. Selection of Local-Scale Study Sites

2.6. Accessibility Analysis

2.7. Conducting and Processing Interviews

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Accessibility Analysis

3.2. Results of the Interviews

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qin, H. Rural-to-Urban Labor Migration, Household Livelihoods, and the Rural Environment in Chongqing Municipality, Southwest China. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Lu, R.; Zhao, N.; Shaw, S.L. An estimate of rural exodus in China using location-aware data. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, K. The rapid urban growth triad: A new conceptual framework for examining the urban transition in developing countries. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalevic, V.; Lakicevic, M.; Radanovic, D.; Billi, P.; Barovic, G.; Vujacic, D.; Sestras, P.; Khaledi Darvishan, A. Ecological-Economic (Eco-Eco) Modelling in the River Basins of Mountainous Regions: Impact of Land Cover Changes on Sediment Yield in the Velicka Rijeka, Montenegro. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2017, 45, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, U.; Zhong, Z.; Tian, B.; Razzaq, A.; Naseer, M.A.R.; Hina, T. Does Rural–Urban Migration Improve Employment Quality and Household Welfare? Evidence from Pakistan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tianming, G.; Ivolga, A.; Erokhin, V. Sustainable Rural Development in Northern China: Caught in a Vice between Poverty, Urban Attractions, and Migration. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alados, C.; Errea, P.; Gartzia, M.; Saiz, H.; Escos, J. Positive and negative feedbacks and free-scale pattern distribution in rural-population dynamics. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H. Remote Rural Regions: How the Proximity to a City Influences the Performances of Rural Regions, Regional Focus No 1; European Commission: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Regional typology: Updated statistics. 2009. Available online: www.oecd.org/gov/regional/statisticsindicators (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Dijkstra, L.; Ruiz, V. Refinement of the OECD Regional Typology: Economic Performance of Remote Rural Regions; Regio, D.G., Ed.; European Commission; OECD: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scardoni, M.; Valentin, M.; Lurye, A. Methodological Manual on Territorial Typologies 2018 edition. In Theme: General and Regional Statistics, Collection: Manuals and Guidelines; Valeriya Angelova-Tosheva, V., Müller, O., Eds.; Eurostat, Unit E4, Regional statistics and geographical informationEurostat; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brajuskovic, M.; Brajuskovic, D.; Mijanovic, D.; Spalevic, V. Indicators of the Regional Differences in the Ageing Population of Montenegro. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2018, 19, 309–318. [Google Scholar]

- Mijanovic, D.; Brajuskovic, M.; Vujacic, D.; Spalevic, V. Causes and Effects of Aging of Montenegrin Population. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2017, 18, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Despotovic, A.; Joksimovic, M.; Svrznjak, K.; Jovanovic, M. Rural areas sustainability: Agricultural diversification and opportunities for agri-tourism development. Agric. For. 2017, 63, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Viñas, C. Depopulation processes in European Rural Areas: A case study of Cantabria (Spain). Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 341–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook; Central Intelligence Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/index.html (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Kranjc, A. History of deforestation and reforestation in the Dinaric Karst. Geogrl Res. 2008, 47, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl., A.; Lenaerts, T.; Radusinovic, S.; Spalevic, V.; Nyssen, J. The regional geomorphology of Montenegro mapped using land surface parameters. Z. Für Geomorphol. 2016, 60, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerckhof, A.; Spalevic, V.; Eetvelde, V.V.; Nyssen, J. Factors of land abandonment in mountainous Mediterranean areas: The case of Montenegrin settlements. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyssen, J.; Van den Branden, J.; Spalevic, V.; Frankl, A.; Van de Velde, L.; Curovic, M.; Billi, P. Twentieth century land resilience in Montenegro and consequent hydrological response. Land Degrad. Dev. 2014, 25, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, M. Eastern Europe 1939–2000; Arnold: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Perosevic, N. Agriculture development in the Municipality of Niksic (1945-1991). Agric. For. 2020, 66, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.; Crabtree, J.R.; Wiesinger, G.; Dax, T.; Stamou, T.; Fleury, P.; Gutierrez Lazpita, J.; Gibon, A. Agricultural abandonment in mountain areas of Europe: Environmental consequences and policy response. J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 59, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.J. Serbia and Montenegro. In Eastern Europe. An introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture; Frucht, R., Ed.; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 529–581. [Google Scholar]

- Lazic, M.; Sekelj, L. Privatisation in Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro). Eur.-Asia Stud. 1997, 49, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MONSTAT—Statistics Office. Statistical Yearbook for 2018; MONSTAT: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MONSTAT—Statistical Office. First Results—Census of Population, Households and Apartments in Montenegro; MONSTAT: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MONSTAT—Statistics Office. Census tables: Table O4 Age and Gender; MONSTAT: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MONSTAT—Statistical Office. Comparative Population Survey 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991 and 2003—Settlement Data; MONSTAT: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MONSTAT—Statistical Office. MONSTAT—Statistics Directorate: Monthly Review, Bulletins for 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018; MONSTAT: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Radojicic, B. Niksic Municipality, Nature and Social Development; Faculty of Philosophy in Niksic and Niksic Municipality: Niksic, Montenegro, 2010. [Google Scholar]

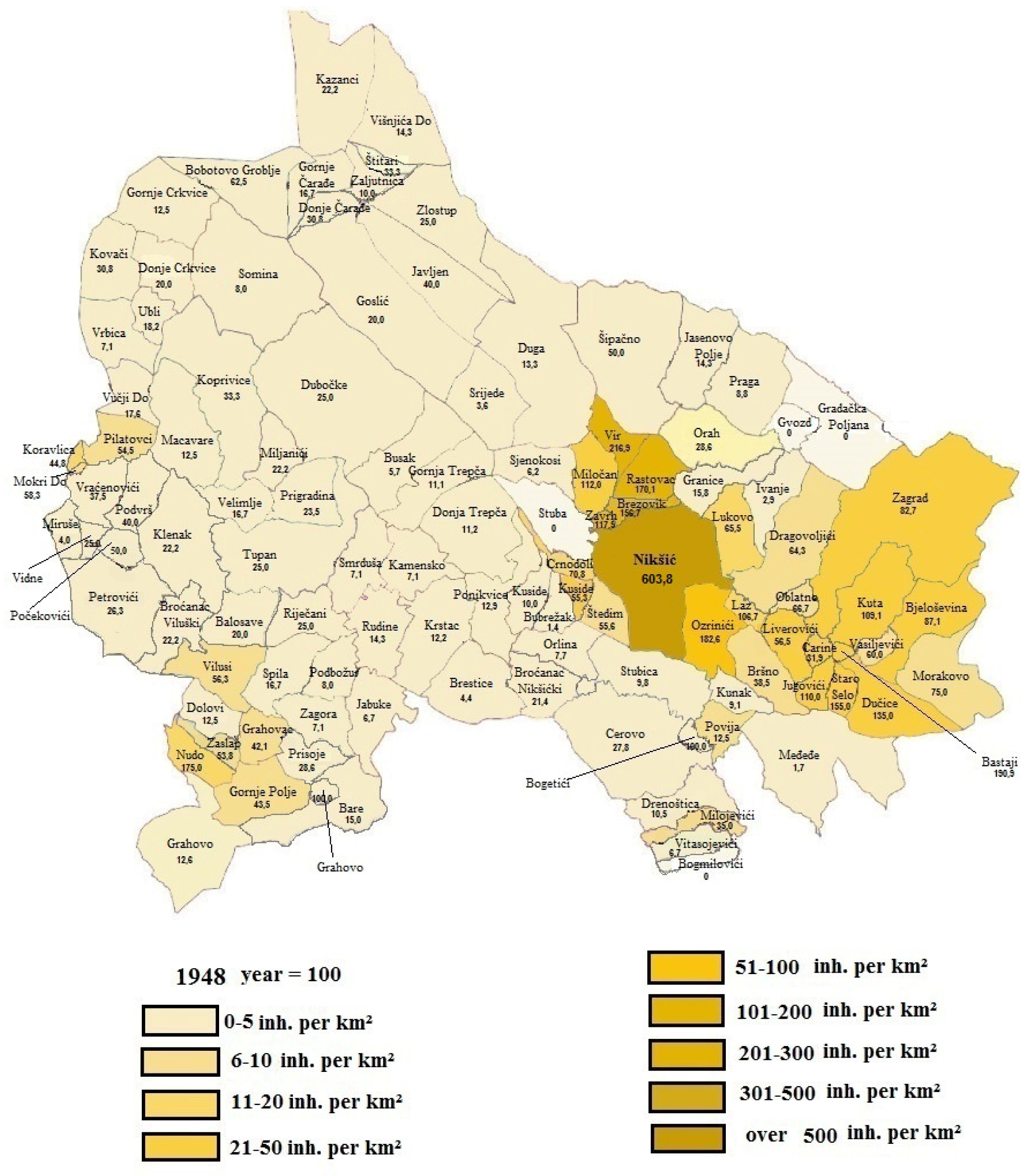

- Mijanovic, D. Changes of population density in the municipality of Niksic as a result of migration. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic 2014, 64, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalevic, V.; Dlabac, A.; Jovović, Z.; Rakočević, J.; Radunović, M.; Spalevic, B.; Fuštić, B. The Surface and distance Measuring Program. Acta Agric. Serbica. 1999, 4, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Spalevic, V. Impact of Land Use on Runoff and Soil Erosion in Polimlje. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Agriculture of the University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Spalevic, V. Assessment of Soil Erosion Processes by Using the ‘IntErO’ Model: Case Study of the Duboki Potok, Montenegro. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2019, 20, 657–665. [Google Scholar]

- Chalise, D.; Kumar, L.; Spalevic, V.; Skataric, G. Estimation of Sediment Yield and Maximum Outflow Using the IntErO Model in the Sarada River Basin of Nepal. Water 2019, 11, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujacic, D.; Barovic, G.; Djekovic, V.; Andjelkovic, A.; Khaledi Darvishan, A.; Gholami, L.; Jovanovic, M.; Spalevic, V. Calculation of Sediment Yield using the River Basin and Surface and Distance Models: A Case Study of the Sheremetski Potok Watershed, Montenegro. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2017, 18, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-structured Interview and beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerholm, N.; Kayhko, N.; Ndumbaro, F.; Khamis, M. Community stakeholders’ knowledge in landscape assessments-mapping indicators for landscape services. Ecol. Ind. 2012, 18, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hawbaker, T.J.; Radeloff, V.C.; Hammer, R.B.; Clayton, M.K. Road density and landscape pattern in relation to housing density, land ownership, land cover, and soils. Landsc. Ecol. 2004, 20, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, J.; Cramb, R.; Alauddin, M.; Gaydon, D.; Roth, C. Farmers’ perceptions and management of risk in rice/shrimp farming systems in South-West Coastal Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Cui, X.; Li, G.; Bao, C.; Wang, Z.; Ma, H.; Sun, S.; Liu, H.; Luo, K.; Ren, Y. Modelling regional sustainable development scenarios using the Urbanization and Eco-environment Coupler: Case study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 689, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, G.; Du, J.; Jia, Y.; Bai, J. Spatial differentiation characteristics of internal ecological land structure in rural settlements and its response to natural and socio-economic conditions in the Central Plains, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 709, 135932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezcana, A.; Buyuktas, K.; Tulin, S.; Aslanb, A. A multi-criteria model for land valuation in the land consolidation. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, E. Rural restructuring in Hungary in the period of socio-economic transition. GeoJournal 2000, 51, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlanfeldt, K.R. The effect of land use regulation on housing and land prices. J. Urban Econ. 2007, 61, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayer, B.E.J.; Mincato, L.R.; Lammle, L.; Silva, M.P.F.L.; Garofalo, T.F.D.; Servidoni, E.L.; Spalevic, V.; Pereira, Y.S. Hydrosedimentological dynamics in the Guarani Aquifer System, Ribeirão Preto, State of São Paulo, Brazil. Agric. For. 2020, 66, 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, A.S.; Spalevic, V.; Avanzi, J.C.; Nogueira, D.A.; Silva, M.L.N.; Mincato, R.L. Modelling of water erosion by the erosion potential method in a pilot subbasin in southern Minas Gerais. Semin.: Ciências Agrárias 2019, 40, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestraș, P.; Bilașco, Ș.; Roșca, S.; Naș, S.; Bondrea, M.V.; Gâlgău, R.; Vereș, I.; Sălăgean, T.; Spalevic, V.; Cîmpeanu, S.M. Landslides Susceptibility Assessment Based on GIS Statistical Bivariate Analysis in the Hills Surrounding a Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palevic, M.; Spalevic, V.; Skataric, G.; Milisavljevic, B.; Spalevic, Z.; Rapajic, B. Environmental responsibility of member states of the European Union. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2019, 20, 886–895. [Google Scholar]

- El Mouatassime, S.; Boukdir, A.; Karaoui, I.; Skataric, G.; Nacka, M.; Khaledi Darvishan, A.; Sestras, P.; Spalevic, V. Modelling of soil erosion processes and runoff for sustainable watershed management: Case study Oued el Abid Watershed, Morocco. Agric. For. 2019, 65, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.Q.; Jiang, G.H.; Zhang, R.J.; Li, Y.L.; Jiang, X.G. Achieving rural spatial restructuring in China: A suitable framework to understand how structural transitions in rural residential land differ across peri-urban interface? Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Village | Latitude | Longitude | Shortest Distance | Driving Distance | Driving Distance | Position to Niksic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suburban | Milocani | 42°49’39.2” N | 18°54’11.1” E | 7.07 km | 8.6 km | 0 h 14 min | NW |

| Ozrinici | 42°45’04.7” N | 19°00’02.8” E | 4.57 km | 5.7 km | 0 h 09 min | SE | |

| Dragovolji | 42°46’24.3” N | 19°02’37.7” E | 7.30 km | 11.4 km | 0 h 17 min | E | |

| Greater Suburban | Sipacno | 42°52’22.4” N | 18°56’45.4” E | 11.01 km | 14.8 km | 0 h 21 min | N |

| Bogetici | 42°40’55.3” N | 18°58’44.0” E | 11.28 km | 14.7 km | 0 h 19 min | S | |

| Carine | 42°43’40.3” N | 18°36’16.0” E | 09.00 km | 14.9 km | 0 h 20 min | W | |

| Mountainous | Grahovo | 42°39’10.3” N | 18°40’08.0” E | 27.00 km | 46.4 km | 0 h 44 min | SW |

| Nudo | 42°40’18.7” N | 18°34’25.2” E | 33.00 km | 60.0 km | 1 h 05 min | SW | |

| Vilusi | 42°43’38.4” N | 18°35’38.0” E | 30.00 km | 35.6 km | 0 h 35 min | W |

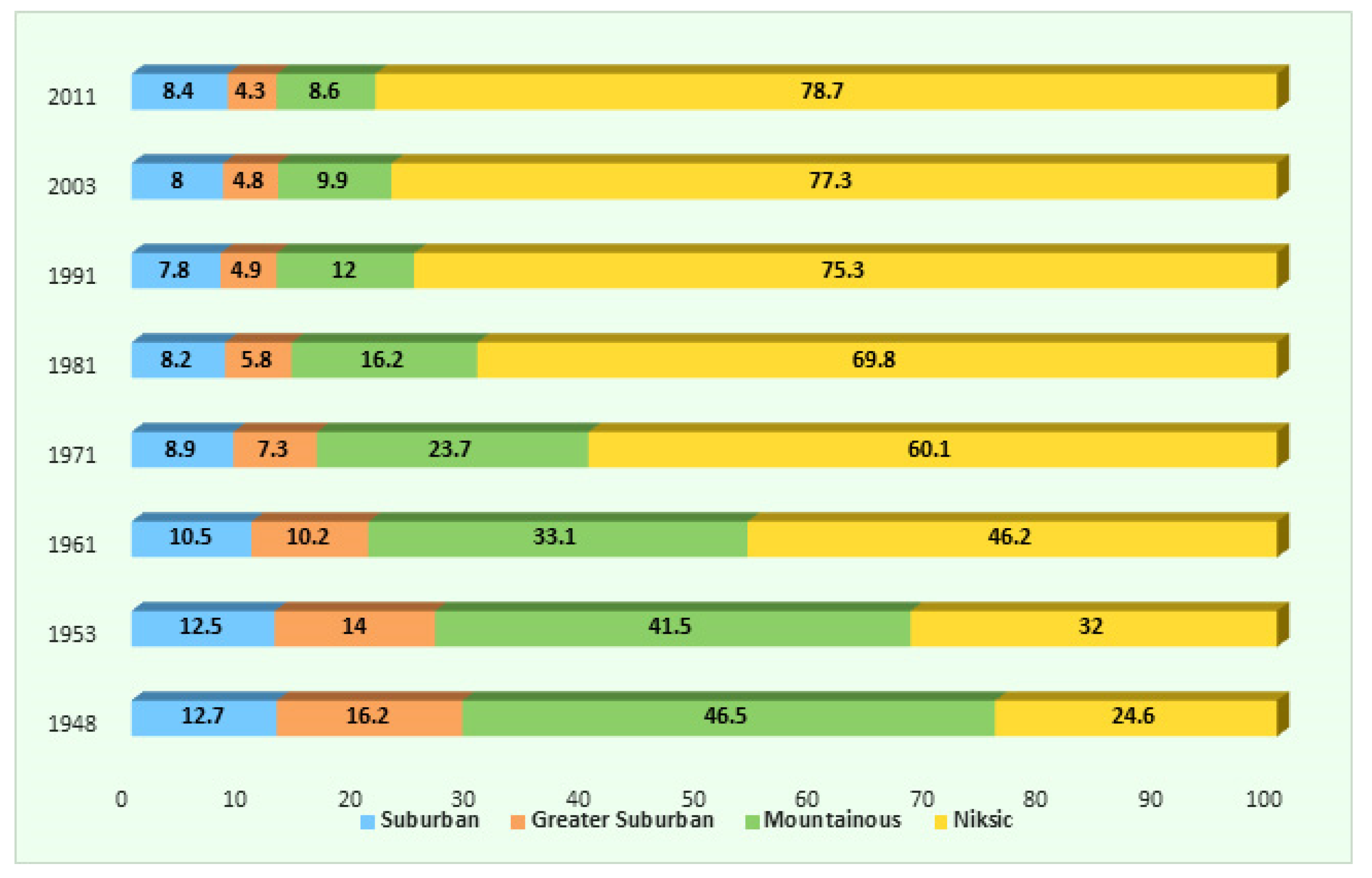

| Settlement | 1948 | 1953 | Index 53/48 | 1961 | Index 61/53 | 1971 | Index 71/61 | 1981 | index 81/71 | 1991 | Index 91/81 | 2003 | Index 03/91 | 2011 | Index 11/03 | Index 11/48 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | 38,359 | 46,589 | 121.5 | 57,399 | 123.2 | 66,815 | 116.4 | 72,299 | 108.2 | 73,878 | 101.9 | 75,282 | 101.9 | 72,443 | 96.2 | 188.9 |

| Nikšić | 9435 | 14,868 | 157.6 | 26,518 | 178.4 | 40,107 | 151.2 | 50,399 | 125.7 | 55,649 | 110.4 | 58,212 | 104.6 | 56,970 | 97.9 | 603.8 |

| Suburban | 4881 | 5844 | 119.7 | 6025 | 103.1 | 5957 | 98.9 | 5964 | 100.1 | 5748 | 96.4 | 6039 | 105.1 | 6113 | 101.2 | 125.2 |

| Greater Suburban | 6206 | 6537 | 105.3 | 5869 | 89.8 | 4889 | 83.3 | 4197 | 85.8 | 3641 | 98.5 | 3588 | 98.5 | 3119 | 86.9 | 50.3 |

| Mountainous | 17,837 | 19,340 | 108.4 | 18,987 | 98.2 | 15,862 | 83.5 | 11,739 | 74.0 | 8840 | 84.2 | 7443 | 84.2 | 6241 | 83.9 | 35.0 |

| Rural settlements | 28,924 | 31,721 | 109.7 | 30,881 | 97.4 | 26,708 | 86.5 | 21,900 | 82.0 | 18,229 | 93.6 | 17,070 | 93.6 | 15,473 | 90.6 | 53.5 |

| Settlement | 1948 | 1953 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2003 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | 18.6 | 22.6 | 27.8 | 32.4 | 35.0 | 35.8 | 36.5 | 35.1 |

| Nikšić | 148.8 | 234.5 | 418.3 | 632.6 | 794.9 | 877.7 | 918.2 | 898.6 |

| Suburban | 32 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 37 | 39 | 40.8 |

| Greater Suburban | 17 | 19 | 20 | 17 | 15 | 13 | 13 | 10.5 |

| Mountainous | 11.5 | 12.4 | 12.2 | 10.2 | 7.6 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 4.0 |

| Rural settlements | 14.5 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 13.3 | 10.9 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 7.7 |

| Year | Settlement Zone | Younger than 20 (%) | Younger than 40 (%) | Up to 60 and Older (%) | Age 1 Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Suburban | 45 | 74 | 12.4 | 0.27 |

| Greater Suburban | 43.4 | 69.8 | 13 | 0.3 | |

| Mountainous | 43.7 | 69.9 | 13.9 | 0.32 | |

| Town-Niksic | 42 | 82.1 | 6.1 | 0.14 | |

| Municipality | 43.1 | 76 | 10.2 | 0.23 | |

| 2011 | Suburban | 27.4 | 54.5 | 19.0 | 0.69 |

| Greater Suburban | 24.7 | 50.4 | 24.8 | 1.01 | |

| Mountainous | 21.1 | 43.9 | 28.8 | 1.37 | |

| Town-Niksic | 26.1 | 54.8 | 17.8 | 0.68 | |

| Municipality | 25.7 | 53.6 | 19.1 | 0.74 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mickovic, B.; Mijanovic, D.; Spalevic, V.; Skataric, G.; Dudic, B. Contribution to the Analysis of Depopulation in Rural Areas of the Balkans: Case Study of the Municipality of Niksic, Montenegro. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083328

Mickovic B, Mijanovic D, Spalevic V, Skataric G, Dudic B. Contribution to the Analysis of Depopulation in Rural Areas of the Balkans: Case Study of the Municipality of Niksic, Montenegro. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083328

Chicago/Turabian StyleMickovic, Biljana, Dragica Mijanovic, Velibor Spalevic, Goran Skataric, and Branislav Dudic. 2020. "Contribution to the Analysis of Depopulation in Rural Areas of the Balkans: Case Study of the Municipality of Niksic, Montenegro" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083328

APA StyleMickovic, B., Mijanovic, D., Spalevic, V., Skataric, G., & Dudic, B. (2020). Contribution to the Analysis of Depopulation in Rural Areas of the Balkans: Case Study of the Municipality of Niksic, Montenegro. Sustainability, 12(8), 3328. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083328