Young Pioneers, Vitality, and Commercial Gentrification in Mudan Street, Changchun, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Study Area and Method

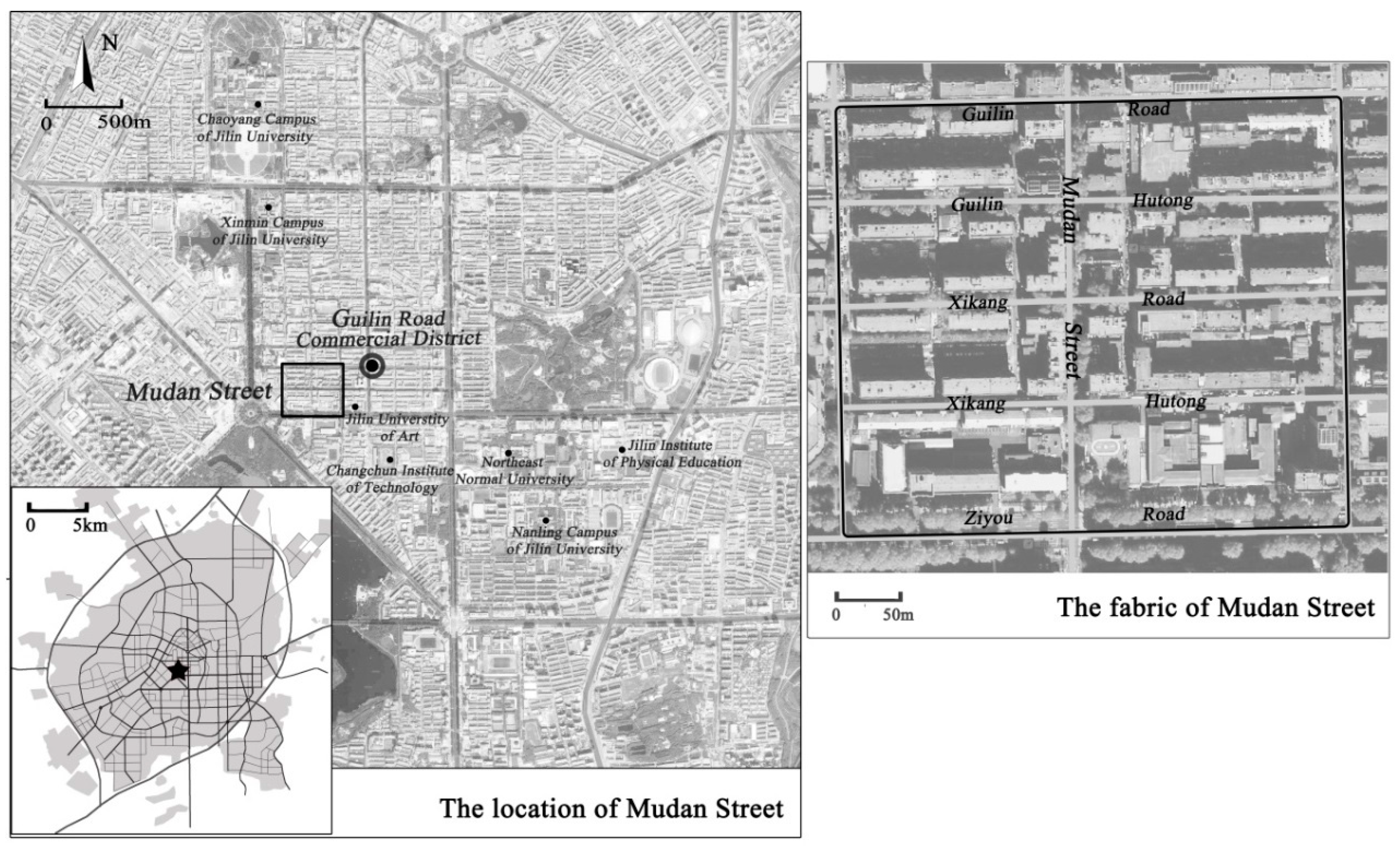

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Method

4. Young Pioneers and Commercial Gentrification in Mudan Street

4.1. Young Pioneers in Mudan Street

4.2. Cafés of Young Pioneers’

4.2.1. “Utopia” for Young Operators

4.2.2. “Home-Like Place” for Urban Youth

4.2.3. “Small Stages” for Artistic Youth

4.3. Effects

4.3.1. Positive Effects in Early Stage of Gentrification

4.3.2. Displacement Effects in the Next Stage of Gentrification

5. Policies and Street Renewal

6. Conclusions and Discussion

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.L.; Hu, J.; Shitmore, M.; Leung, B.Y.P. Inner-city urban redevelopment in china metropolises and the emergence of gentrification: Case of yuexiu, guangzhou. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2014, 140, 05014004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, K. Building soho in shenzhen: The territorial politics of gentrification and state making in china. Geoforum 2020, 111, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.B.; Zhu, X.G.; Li, J.S.; Sun, J.; Huang, Q.S. Progress of gentrification research in china: A bibliometric review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.W.; Yi, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Shrestha, A.; Martek, I.; Wei, L.Z. An evaluation of urban renewal policies of shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaf, M. Inner city redevelopment in china. Cities 1995, 13, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanga, Q.; Zhou, M. Interpreting gentrification in chengdu in the post-socialist transition of China: A sociocultural perspective. Geoforum 2018, 93, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.B. Urban conservation and revalorisation of dilapidated historic quarters: The case of nanluoguxiang in beijing. Cities 2010, 27, S43–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Park, J. Stage classification and characteristics analysis of commercial gentrification in seoul. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocejo, R.E. The early gentrifier: Weaving a nostalgia narrative on the lower east side. City Community 2011, 10, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- BaeKim, W. The viability of cultural districts in seoul. City Cult. Soc. 2011, 2, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Miles, S.; Stark, P. Culture-led urban regeneration and the revitalisation of identities in newcastle, gateshead and the north east of england. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2004, 10, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S. From fabrics to fine arts: Urban restructuring and the formation of an art district in shanghai. Crit. Plan. 2009, 16, 118–137. [Google Scholar]

- Blasius, J.; Friedrichs, J.; Rühl, H. Pioneers and gentrifiers in the process of gentrification. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2016, 16, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, L.; Slater, T.; Wyly, E. Gentrification; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Saracino, J. The Gentrification Debates; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, R.; Bridge, G. Gentrification in a Global Context; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Toward a theory of gentrification a back to the city movement by capital, not people. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1979, 45, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamnett, C. The blind men and the elephant: The explanation of gentrification. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1991, 16, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamnett, C.; Randolph, B. Chapter nine the role of labour and housing markets in the production of geographical variations in social stratification. In Politics, Geography, and Social Stratification; Croom Helm: London, UK, 1986; p. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. Gentrification and the rent gap. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1987, 77, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, D. Liberal ideology and the postindustrial city. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1980, 70, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T. Gentrification and the Middle Classes; Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Warde, A. Gentrification as consumption: Issues of class and gender. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1991, 9, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.; Chris, C.; Ramsden, M. Inward and upward: Marking out social class change in London. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. Gentrification: Culture and capital in the urban core. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 1987, 13, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, L. Gentrification in London and New York: An atlantic gap? Hous. Stud. 1994, 9, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, L.; Slater, T.; Wyly, E. The Gentrification Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, R. Neo-Bohemia: Art and Commerce in the Postindustrial City; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J. Pioneers of gentrification: Transformation in global neighborhoods in urban America in the late twentieth century. Demography 2016, 53, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, J.; Hannam, K. ‘The secret garden’: Artists, bohemia and gentrification in the Ouseburn valley, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 24, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, J. Neoliberal Culture; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, S. Artists and Shanghai’s culture-led urban regeneration. Cities 2016, 56, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darren, P.S.; Joanna, S.; Stacey, B. The geographies of studentification: Here, ‘there and everywhere’? Geography 2014, 99, 116–127. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.J. Consuming urban living in “villages in the city”: Student fication in guangzhou china. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2849–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, T. Expanding the scope of studentification studies. Geogr. Compass 2017, 11, e12300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivant, E. The (re)making of Paris as a bohemian place? Prog. Plan. 2010, 74, 107–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, G. ‘This place gives me space’: Place and creativity in the creative industries. Geoforum 2003, 34, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, L.; Butler, T. Super-gentrification in Barnsbury, London: Globalization and gentrifying global elites at the neighbourhood level. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2006, 31, 467–487. [Google Scholar]

- Bounds, M.; Morris, A. Second wave gentrification in inner-city Sydney. Cities 2006, 23, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. ‘Art in capital’: Shaping distinctiveness in a culture-led urban regeneration project in red town, Shanghai. Cities 2009, 26, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.R.; Stevens, Q. How culture and economy meet in South Korea: The politics of cultural economy in culture-led urban regeneration. Int. J. Urban Res. 2013, 37, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.; Lees, L. Artists, aestheticisation and the field of gentrification. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2006, 31, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makagon, D. Bring on the shock troops: Artists and gentrification in the popular press. Commun. Crit. Cult. Stud. 2010, 7, 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocka, M.; Schmiz, A. Catering authenticities. Ethnic food entrepreneurs as agents in berlin’s gentrification. City Cult. Soc. 2019, 18, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstenbach, C.; Boterman, W. Chapter 11: Age, life course and generations in gentrification processes. In Handbook of Gentrification Studies; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. There Goes the Hood: Views of Gentrification from the Ground Up; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S.; Trujillo, V.; Frase, P.; Jackson, D.; Recuber, T.; Walker, A. New retail capital and neighborhood change: Boutiques and gentrification in New York city. City Community 2009, 8, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S.; Kasinitz, P.; Chen, X.M. Global Cities, Local Streets: Everyday Diversity from New York to Shanghai; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bantman-Masum, E. Unpacking commercial gentrification in central Paris. Urban Stud. 2019, 00, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingping, G. The characteristics of consumption culture of the generation born after 1980s: Secular romanticism. Contemp. Youth Res. 2008, 3, 7–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ocejo, R.E. Upscaling Downtown: From Bowery Saloons to Cocktail Bars in New York City; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C. “I think home is more than a building”: Young home(less) people on the cusp of home, self and something else. Urban Policy Res. 2002, 20, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M. The idea of a home: A kind of space. Soc. Res. 1991, 58, 287–307. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, S. Socially inclusive cultural policy and arts-based urban community regeneration. Cities 2010, 27, S16–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. A creative, dynamic city is an open, tolerant city. Globe Mail. 2002, 24, T8. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Year of Set Up Café | Gender | Age * | Interview Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O01 | 2004 | Female | 26 | October 2012 |

| O02 | 2004 | Male | 24 | October 2012, July 2015, June 2017 |

| O03 | 2009 | Male | 33 | October 2012, July 2015, June 2017 |

| O04 | 2009 | Male | 30 | October 2012 |

| O05 | 2009 | Female | 22 | October 2012 |

| O06 | 2010 | Male | 22 | October 2012, July 2015 |

| O07 | 2011 | Male | 36 | October 2012 |

| O08 | 2012 | Male | 24 | October 2012, July 2015 |

| O09 | 2012 | Male | 27 | October 2012 |

| O10 | 2013 | Male | 31 | July 2015, June 2017 |

| O11 | 2013 | Female | 23 | July 2015 |

| O12 | 2014 | Female | 24 | July 2015, June 2017 |

| O13 | 2015 | Male | 22 | July 2015 |

| O14 | 2015 | Male | 22 | June 2017 |

| O15 | 2015 | Female | 23 | June 2017 |

| O16 | 2016 | Female | 24 | June 2017 |

| No. | Gender | Age * | Status | Interview Time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actors | A01 | Male | 27 | Lounge singer, Artist | July 2015 |

| A02 | Male | 24 | Cross talker | October 2012 | |

| A03 | Male | 26 | Photographer | October 2012 | |

| Consumers | C01 | Female | 28 | Editor | October 2012 |

| C02 | Female | 22 | University student | July 2015 | |

| C03 | Male | 25 | Office clerk | July 2015 | |

| C04 | Male | 27 | Office clerk | June 2017 | |

| C05 | Female | 26 | Teacher | July 2015 |

| Feature | Number of Responses | Percentage (%) | Feature | Number of Responses | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | * Motivation for setting up a café | ||||

| Male | 10 | 62.5 | Make money | 16 | 100.0 |

| Female | 6 | 37.5 | Build an ideal space for oneself | 14 | 87.5 |

| The age at which the café set up | Share favorite things with friends | 13 | 81.3 | ||

| 20–25 | 10 | 62.5 | Office work makes limited income and little freedom | 9 | 56.3 |

| 26-30 | 2 | 12.5 | * Reasons for locating in Mudan Street | ||

| >30 | 4 | 25.0 | Low rent | 13 | 81.3 |

| Level of education | Adjacent to trendy and youth-oriented shopping district | 11 | 68.8 | ||

| High school | 1 | 6.3 | Silent and leisurely living atmosphere | 6 | 37.5 |

| Undergraduate Degree | 13 | 81.3 | Growing coffee culture | 9 | 56.3 |

| Graduate Degree | 2 | 12.5 | * Sources of financing | ||

| Undergraduate Major | Personal saving | 10 | 62.5 | ||

| Art | 6 | 37.5 | Parents’ support | 9 | 56.3 |

| Literature | 3 | 18.8 | Borrow from friends | 3 | 18.8 |

| Other major | 7 | 43.8 | Social investor | 1 | 6.3 |

| Overseas life experience | * Ways of attracting customers | ||||

| None | 12 | 75.0 | Build chic façade and interior | 16 | 100.0 |

| Study | 2 | 12.5 | Organize cultural activities | 11 | 68.8 |

| Work | 2 | 12.5 | Build social networks with regular customers | 11 | 68.8 |

| Operate a café as a | Provide a comfortable and warm place | 10 | 62.5 | ||

| Part time job | 6 | 37.5 | Provide special drink and food | 4 | 25.0 |

| Main job | 10 | 62.5 | Profitability of the café | ||

| Main job/Old job | Good profit | 2 | 12.5 | ||

| Graduate | 7 | 43.8 | Limited profit | 9 | 56.3 |

| White collar | 9 | 56.3 | No profit | 3 | 18.8 |

| Artist | 3 | 18.8 | Deficit | 2 | 12.5 |

| Editor/Writer | 2 | 12.5 | * Difficulties and risks | ||

| Office clerk | 2 | 12.5 | Rising rent | 16 | 100.0 |

| Lawyer | 1 | 6.3 | Low current capital | 11 | 68.8 |

| Psychologist | 1 | 6.3 | Increasingly fierce competition | 10 | 62.5 |

| Restaurant manager | 1 | 6.3 | Unstable customers | 8 | 50.0 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, W.; Tong, Y.; Li, C. Young Pioneers, Vitality, and Commercial Gentrification in Mudan Street, Changchun, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083113

Zhang J, Ma Z, Li D, Liu W, Tong Y, Li C. Young Pioneers, Vitality, and Commercial Gentrification in Mudan Street, Changchun, China. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083113

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jing, Zuopeng Ma, Dawei Li, Wei Liu, Yao Tong, and Chenggu Li. 2020. "Young Pioneers, Vitality, and Commercial Gentrification in Mudan Street, Changchun, China" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083113

APA StyleZhang, J., Ma, Z., Li, D., Liu, W., Tong, Y., & Li, C. (2020). Young Pioneers, Vitality, and Commercial Gentrification in Mudan Street, Changchun, China. Sustainability, 12(8), 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083113