Education and Disaster Vulnerability in Southeast Asia: Evidence and Policy Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Central Concepts and Terminology

3. Theoretical Framework and Previous Literature

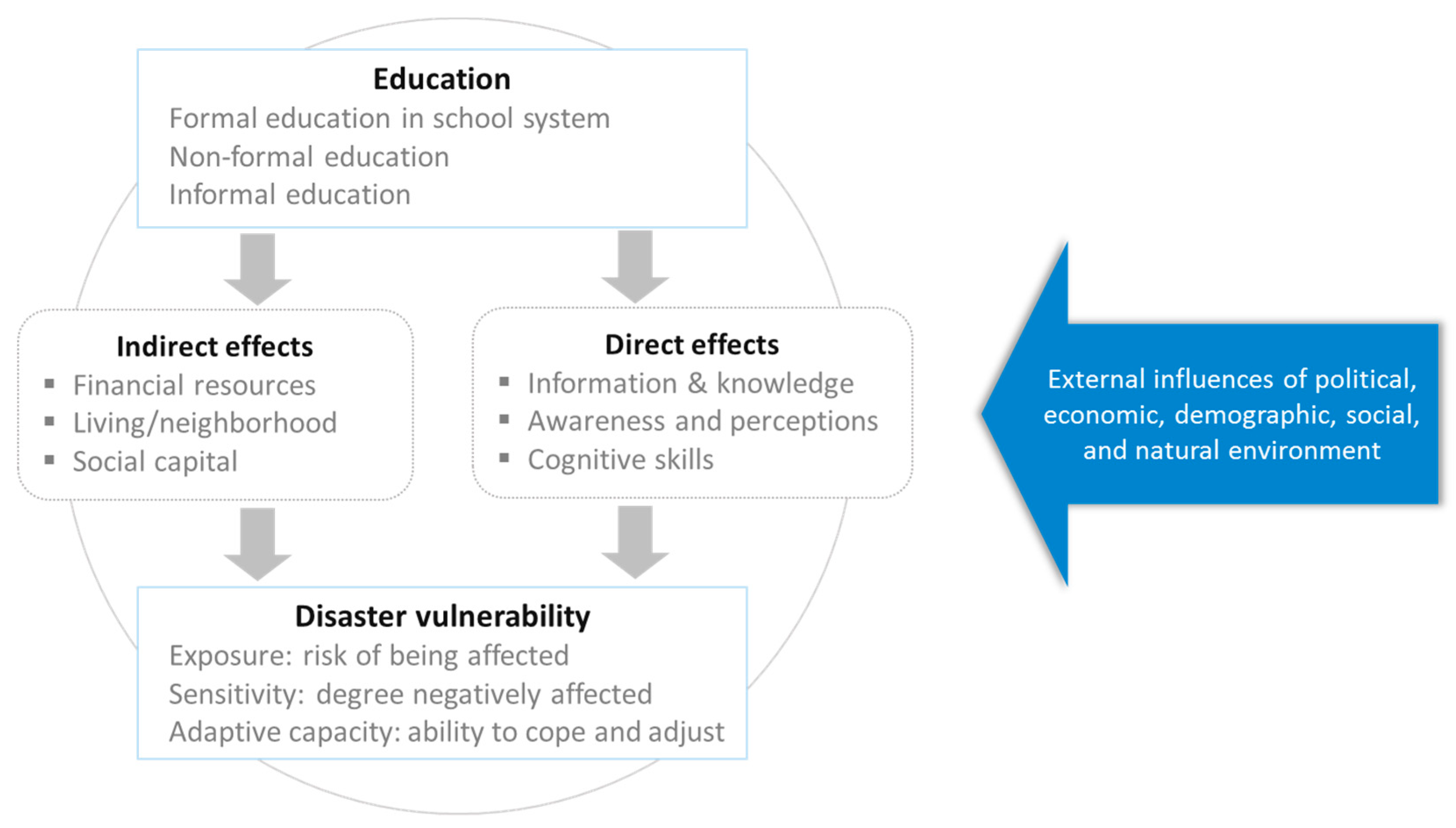

3.1. Education Effects: Understanding the Underlying Mechanisms

3.2. Empirical Evidence: Education Effects on Disaster Vulnerability

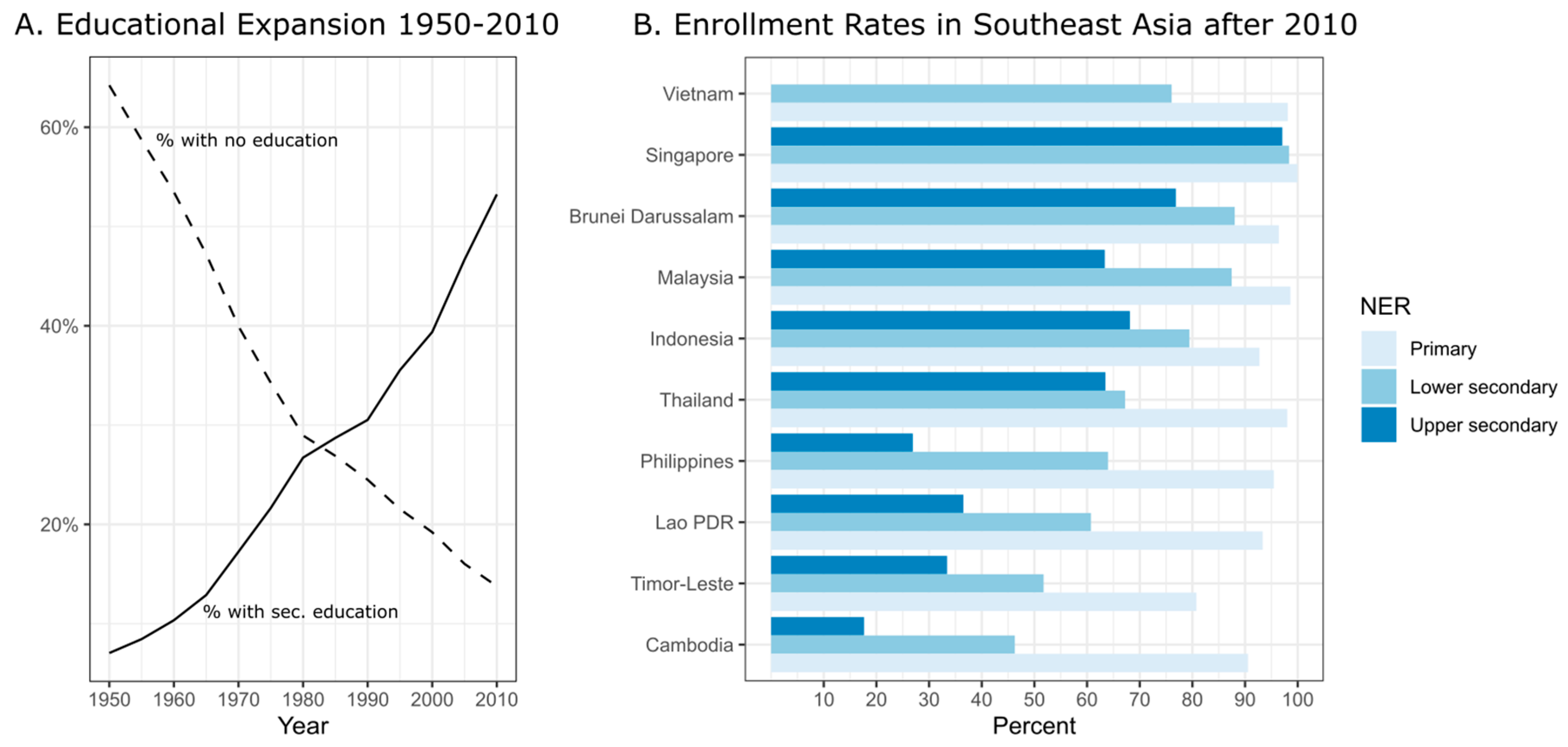

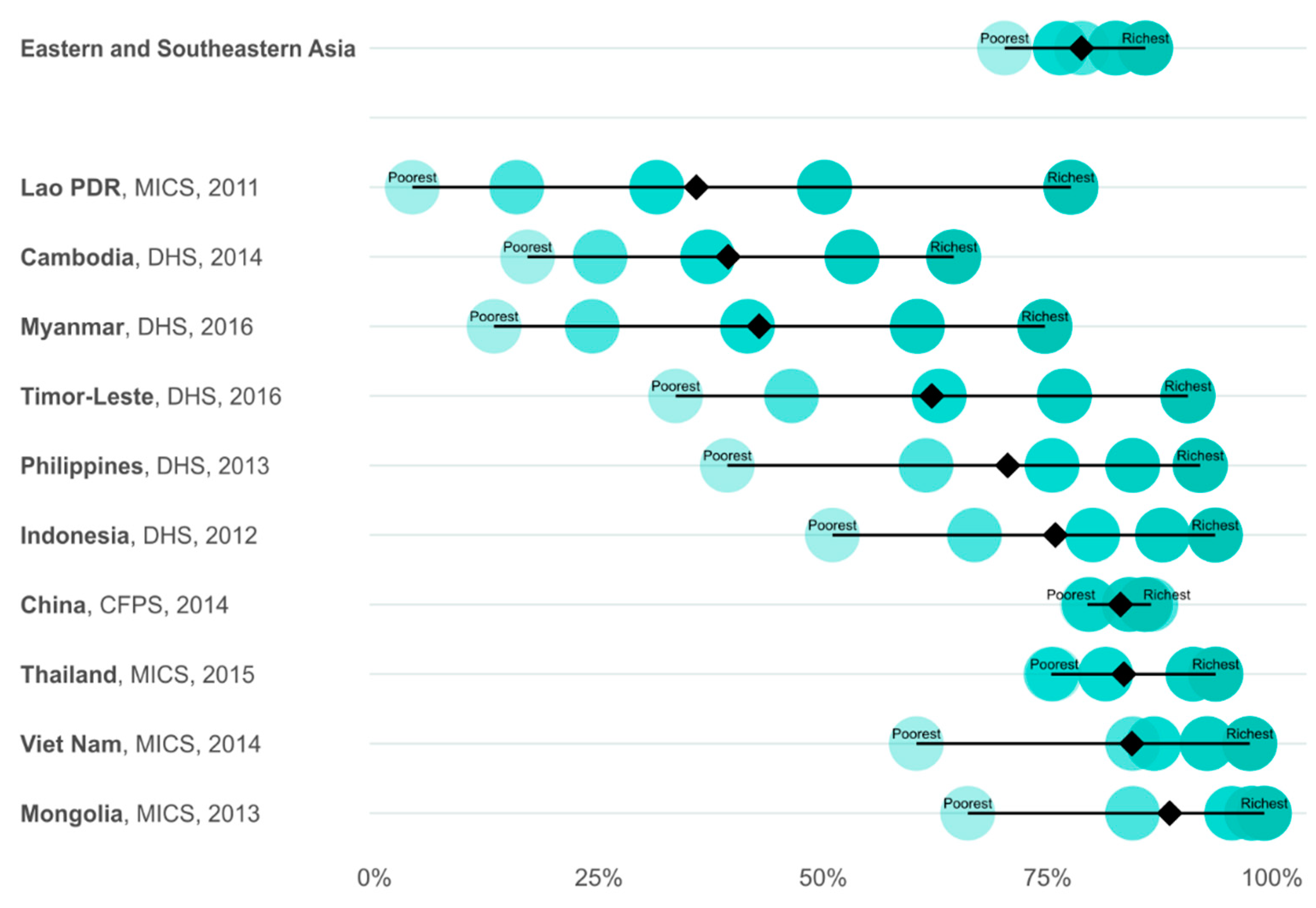

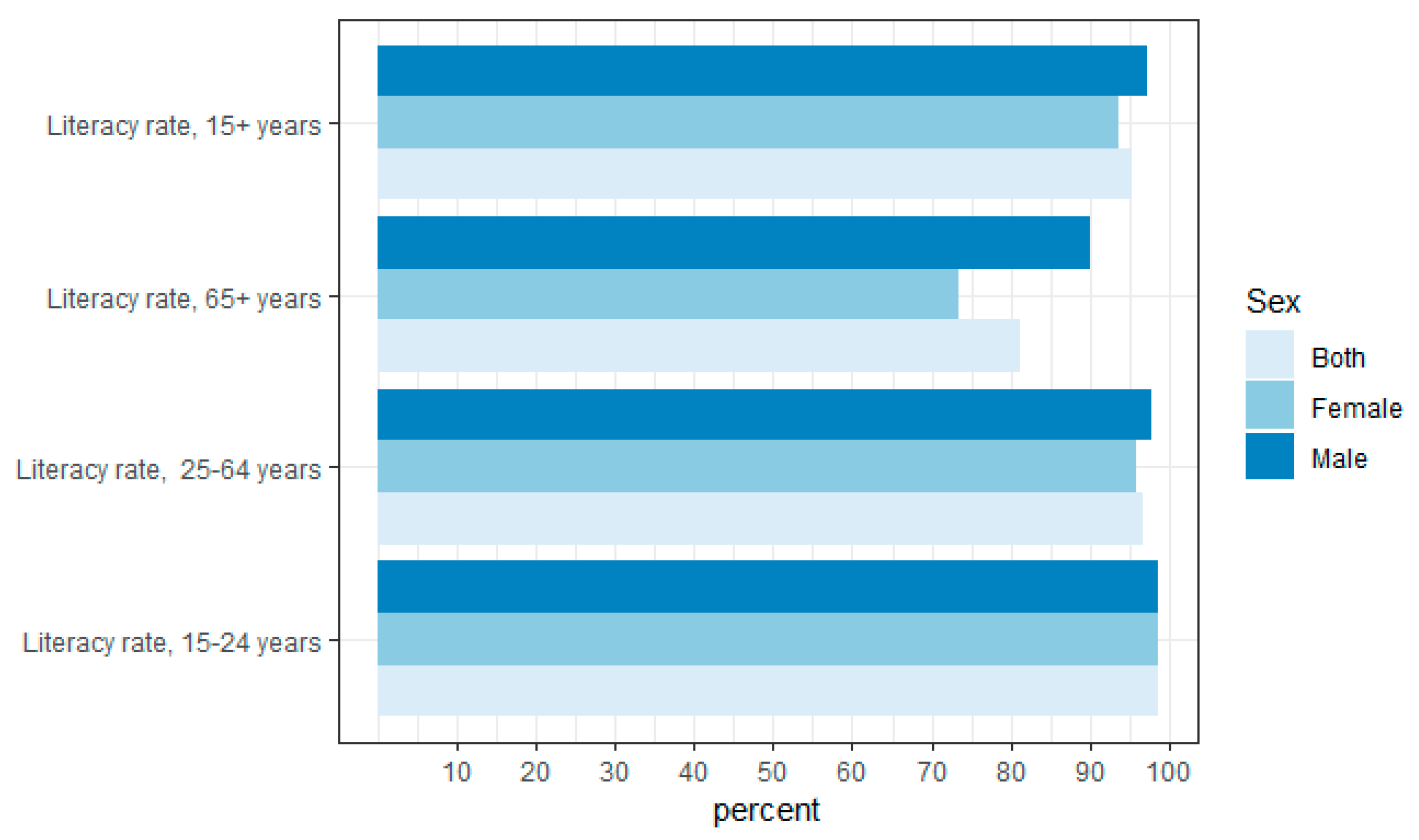

4. Situation Analysis

5. Policy Implications

5.1. Best Practices

5.2. Policy Lessons

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adger, W.N.; Hughes, T.P.; Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Rockström, J. Social-Ecological Resilience to Coastal Disasters Social-Ecological Resilience to Coastal Disasters Social-Ecological Resilience to Coastal Disasters. Science 2012, 309, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.B.; Barros, V.; Stocker, T.F.; Dahe, Q.; Jon Dokken, D.; Ebi, K.L.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Mach, K.J.; Plattner, G.K.; Allen, S.K.; et al. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Cambrdige University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781139177245. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, S.; Barakat, B.; Muttarak, R. The Role of Education in Enabling the Sustainable Development Agenda; Routledge: Abingon-on-Thames, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, W.; Muttarak, R.; Striessnig, E. Universal education is key to enhanced climate adaptation. Science 2014, 346, 1061–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muttarak, R.; Lutz, W. Is Education a Key to Reducing Vulnerability to Natural Disasters and hence Unavoidable Climate Change? Soc. 2014, 1, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, F.; Selby, D. Ready for the Storm: Education for Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigg, J. Disaster risk reduction. Good Pract. Rev. 2015, 9, 1–382. Available online: https://goodpracticereview.org/ (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- UNDRR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/ (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Birkmann, J. Assessing Vulnerability Before, During and After a Natural Disaster in Fragile Regions; UNU WIDER Working Paper 50/2008; UNU WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lagmay, A.M.F.; Agaton, R.P.; Bahala, M.A.C.; Briones, J.B.L.T.; Cabacaba, K.M.C.; Caro, C.V.C.; Dasallas, L.L.; Gonzalo, L.A.L.; Ladiero, C.N.; Lapidez, J.P.; et al. Devastating storm surges of Typhoon Haiyan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Muttarak, R. Learn from the Past, Prepare for the Future: Impacts of Education and Experience on Disaster Preparedness in the Philippines and Thailand. World Dev. 2017, 96, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreve, C.M.; Kelman, I. Does mitigation save? Reviewing cost-benefit analyses of disaster risk reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 10, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Keur, P.; van Bers, C.; Henriksen, H.J.; Nibanupudi, H.K.; Yadav, S.; Wijaya, R.; Subiyono, A.; Mukerjee, N.; Hausmann, H.J.; Hare, M.; et al. Identification and analysis of uncertainty in disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation in South and Southeast Asia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 16, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, S.; Eaton, J.L.; Feroz, S.; Bainbridge, A.A.; Hoolachan, J.; Barnett, D.J. Personal disaster preparedness: An integrative review of the literature. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2012, 6, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatebe, J.; Mutch, C. Perspectives on education, children and young people in disaster risk reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 14, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werquin, P. Recognising Non-Formal and Informal Learning: Outcomes, Policies and Practices; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010; ISBN 9789264063853. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M. Global Perspectives on Recognising Non-formal and Informal Learning: Why Recognition Matters; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-15277-6. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, L.D.; Wolfe, M. Principles and Practice of Informal Education; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marsick, V.J.; Watkins, K.E. Informal and Incidental Learning. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2002, 2001, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; von Krogh, G. Perspective—Tacit Knowledge and Knowledge Conversion: Controversy and Advancement in Organizational Knowledge Creation Theory. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 481–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, C. Narrative and social tacit knowledge. J. Knowl. Manag. 2001, 5, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselgartner, J.; Pigeon, P. The Role of Knowledge in Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2015, 6, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In IPCC Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 9789291691432.

- Zagheni, E.; Muttarak, R.; Striessnig, E. Differential mortality patterns from hydro-meteorological disasters: Evidence from cause-of-death data by age and sex. Vienna Yearb. Popul. Res. 2015, 13, 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Muttarak, R.; Lutz, W.; Jiang, L. Introduction: What can demographers contribute to the study of vulnerability? Vienna Yearb. Popul. Res. 2015, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, D.; Johnston, D. Disasters and communities: Vulnerability, resilience and preparedness. Disaster Prev. Manag. An Int. J. 2001, 10, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR. UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction; UNDRR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/2009-unisdr-terminology-disaster-risk-reduction (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.; Gamson, D.; Thorne, S.; Baker, D. Rising mean IQ: Cognitive demand of mathematics education for young children, population exposure to formal schooling, and the neurobiology of the prefrontal cortex. Intelligence 2005, 33, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, S.J. How much does schooling influence general intelligence and its cognitive components? A reassessment of the evidence. Dev. Psychol. 1991, 27, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J. Review of intelligence and how to get it: Why schools and cultures count. Intelligence 2010, 48, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Eslinger, P.J.; Blair, C.; Wang, J.L.; Lipovsky, B.; Realmuto, J.; Baker, D.; Thorne, S.; Gamson, D.; Zimmerman, E.; Rohrer, L.; et al. Developmental shifts in fMRI activations during visuospatial relational reasoning. Brain Cogn. 2009, 69, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quartz, S.R.; Sejnowski, T.J. The neural basis of cognitive development: A constructivist manifesto. Behav. Brain Sci. 1997, 20, 537–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, W.; Parker, A.M.; Fischhoff, B. Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.; Västfjäll, D.; Slovic, P.; Mertz, C.K.; Mazzocco, K.; Dickert, S. Numeracy and decision making. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birru, M.S.; Monaco, V.M.; Charles, L.; Drew, H.; Njie, V.; Bierria, T.; Detlefsen, E.; Steinman, R.A. Internet usage by low-literacy adults seeking health information: An observational analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.B.; Tanwar, M.; Richter, J.V.E. Evaluation of online disaster and emergency preparedness resources. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2008, 23, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Functional Literacy. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/node/334638 (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Brown, L.M.; Haun, J.N.; Peterson, L. A proposed disaster literacy model. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2014, 8, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.; Heckman, J.; Yi, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, S. Education and preferences: Experimental Evidence from Chinese Adult Twins; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oreopoulos, P.; Salvanes, K.G. Priceless: The Nonpecuniary Benefits of Schooling. J. Econ. Perspect. 2011, 25, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, M. Education and Nonmarket Outcomes. In Handbook of the Economics of Education; Hanushek, E., Welch, F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2006; pp. 577–633. ISBN 9780444513991. [Google Scholar]

- Card, D. The causal effect of education on earnings. In Handbook of Labor Economics; Ashenfelter, O., Card, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 1999; pp. 1801–1863. ISBN 9780444501875. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J.J.; Humphries, J.E.; Veramendi, G. Returns to Education: The Causal Effects of Education on Earnings, Health, and Smoking. J. Polit. Econ. 2018, 126, 197–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotten, S.R.; Gupta, S.S. Characteristics of online and offline health information seekers and factors that discriminate between them. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 1795–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuenschwander, L.M.; Abbott, A.; Mobley, A.R. Assessment of low-income adults’ access to technology: Implications for nutrition education. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.M.; Rissel, C.; Baur, L.A.; Lee, E.; Simpson, J.M. Who is NOT likely to access the Internet for health information? Findings from first-time mothers in southwest Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2011, 80, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; McCright, A.M. Environmental concern and sociodemographic variables: A study of statistical models. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 38, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, H.; Dıaz, W.; Santos, J.M.; Aguirre, B.E. Communicating Risk and Uncertainty: Science, Technology, and Disasters at the Crossroads. In Handbook of Disaster Research; Rodriguez, H., Quarantelli, E.L., Dynes, R.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 476–488. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; van den Brink, H.; Groot, W. A meta-analysis of the effect of education on social capital. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2009, 28, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, R.L.D.; Huckfeldt, R. Social capital, social networks, and political participation. Polit. Psychol. 1998, 19, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschenbaum, A. Families and Disaster Behavior: A Reassessment of Family Preparedness. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disasters 2006, 24, 111–143. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg, C.; Rossetto, T.; Joffe, H. The social psychology of seismic hazard adjustment: Re-evaluating the international literature. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 1663–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witvorapong, N.; Muttarak, R.; Pothisiri, W. Social participation and disaster risk reduction behaviors in tsunami prone areas. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamsler, C.; Brink, E.; Rentala, O. Climate change, adaptation, and formal education: The role of schooling for increasing societies’ adaptive capacities in El Salvador and Brazil. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, S. Community vulnerability to floods and landslides in Nepal. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, U.; Patwardhan, A.; Patt, A.G. Education as a determinant of response to cyclone warnings: Evidence from coastal zones in India. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, L.A.; Goltz, J.D.; Bourque, L.B. Preparedness and Hazard Mitigation Actions before and after Two Earthquakes. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 744–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.J. Household preparedness for the Aftermath of Hurricanes in Florida. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Smith, T.; Kaniasty, K. Revisiting the experience-behavior hypothesis: The effects of Hurricane Hugo on hazard preparedness and other self-protective acts. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 1999, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Reininger, B.M.; Rahbar, M.H.; Lee, M.J.; Chen, Z.; Alam, S.R.; Pope, J.; Adams, B. Social capital and disaster preparedness among low income Mexican Americans in a disaster prone area. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 83, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lave, T.R.; Lave, L.B. Public Perception of the Risks of Floods: Implications for Communication. Risk Anal. 1991, 11, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieken, A.H.; Kreibich, H.; Müller, M.; Merz, B. Coping with floods: Preparedness, response and recovery of flood-affected residents in Germany in 2002. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2007, 52, 1016–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttarak, R.; Pothisiri, W. The role of education on disaster preparedness: Case study of 2012 Indian Ocean earthquakes on Thailand’s Andaman coast. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rousan, T.M.; Rubenstein, L.M.; Wallace, R.B. Preparedness for natural disasters among older US adults: A nationwide survey. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.L.; Notaro, S.J. Personal emergency preparedness for people with disabilities from the 2006-2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Disabil. Health J. 2009, 2, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichler, A.; Striessnig, E. Differential vulnerability to hurricanes in Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic: The contribution of education. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberg, E.; Sikoki, B.; Sumantri, C.; Suriastini, W.; Thomas, D. Education, vulnerability, and resilience after a natural disaster. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, A.; Bodin, Ö.; Gelcich, S.; Crona, B. Social capital in post-disaster recovery trajectories: Insights from a longitudinal study of tsunami-impacted small-scale fisher organizations in Chile. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnacci, U. Joining the dots: Social networks and community resilience in post-conflict, post-disaster Indonesia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 16, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmansyah, I.; Dharmono, S.; Maramis, A.; Minas, H. Determinants of psychological morbidity in survivors of the earthquake and tsunami in Aceh and Nias. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2010, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbero, A.; Muttarak, R. Impacts of the 2010 droughts and floods on community welfare in rural Thailand: Differential effects of village educational attainment. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.M. Community-based disaster preparedness and climate adaptation: Local capacity-building in the Philippines. Disasters 2006, 30, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanci, A.N.; Aksit, B.; Dirik, G. Impact of a Community Disaster Awareness Training Program in Turkey: Does it Influence Hazard-Related Cognitions and Preparedness Behaviors. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2006, 33, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R.; Lee, J.-W. A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950-2010. J. Dev. Econ. 2013, 104, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfield, G.; Lee, C. Why Segregation Matters: Poverty and Educational Inequality; Civil Rights Project: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED489186 (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Seth, S.; Santos, M.E. Multidimensional Inequality and Human Development; OPHI Working Paper 114; Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, R.D. Differential vulnerabilities: Environmental and economic inequality and government response to unnatural disasters. Soc. Res. (NY). 2008, 75, 753–784. [Google Scholar]

- Bolin, B.; Kurtz, L.C. Race, Class, Ethnicity, and Disaster Vulnerability. In Handbook of Disaster Research; Rodríguez, H., Donner, W., Trainor, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Donner, W.; Rodriguez, H. Population Composition, Migration and Inequality: The Influence of Demographic Changes on Disaster Risk and Vulnerability. Soc. Forces 2008, 87, 1089–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations General Assembly: New York, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN. Safe School Initiative. Available online: https://aseansafeschoolsinitiative.org/ (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Cornerstone on Demand Foundation Disaster Ready Initiative. Available online: https://www.disasterready.org/ (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- UNESCO. Sai Fah: The Flood Fighter. Available online: https://bangkok.unesco.org/content/sai-fah-flood-fighter (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Plan International & Australian Aid Child Centred Climate Change Adaptation (4CA), Act to Adapt, The Next Generation Leads the Way. Available online: https://plan-international.org/publications/act-adapt-child-centred-climate-change-adaptation (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Hoffmann, R.; Blecha, D. Education and Disaster Vulnerability in Southeast Asia: Evidence and Policy Implications. In Resistance, Resilience, and Recovery from Disasters: Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Perspectives from Southeast Asia; Waelde, L., Hechanova, R.H., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoffmann, R.; Blecha, D. Education and Disaster Vulnerability in Southeast Asia: Evidence and Policy Implications. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041401

Hoffmann R, Blecha D. Education and Disaster Vulnerability in Southeast Asia: Evidence and Policy Implications. Sustainability. 2020; 12(4):1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041401

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoffmann, Roman, and Daniela Blecha. 2020. "Education and Disaster Vulnerability in Southeast Asia: Evidence and Policy Implications" Sustainability 12, no. 4: 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041401

APA StyleHoffmann, R., & Blecha, D. (2020). Education and Disaster Vulnerability in Southeast Asia: Evidence and Policy Implications. Sustainability, 12(4), 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041401