A Governance Approach to Regional Energy Transition: Meaning, Conceptualization and Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Regional Energy Transition in the Innovation and Transition Literature

2.1. Regional Innovation Studies

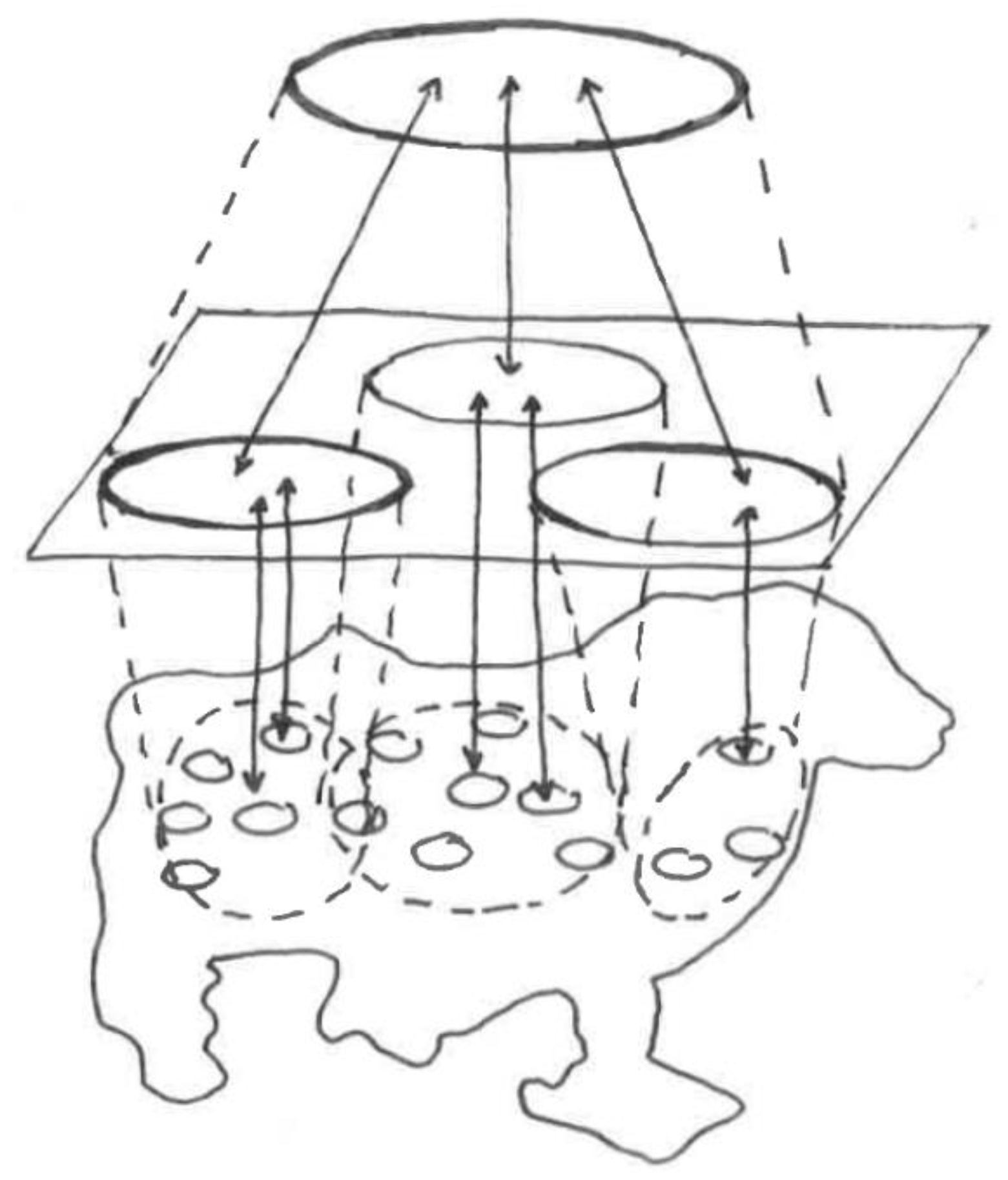

2.2. Transition Studies

3. Regional Energy Transition in the Governance Literature

3.1. Regional Governance

3.2. Network Governance

3.3. Governance Studies and Energy Transition at the Regional Scale

4. Towards a Conceptual Framework to Address Governance of Regional Energy Transition

5. Research Design and Methodology

5.1. Case Selection

5.2. Data Collection and Analysis

6. Results

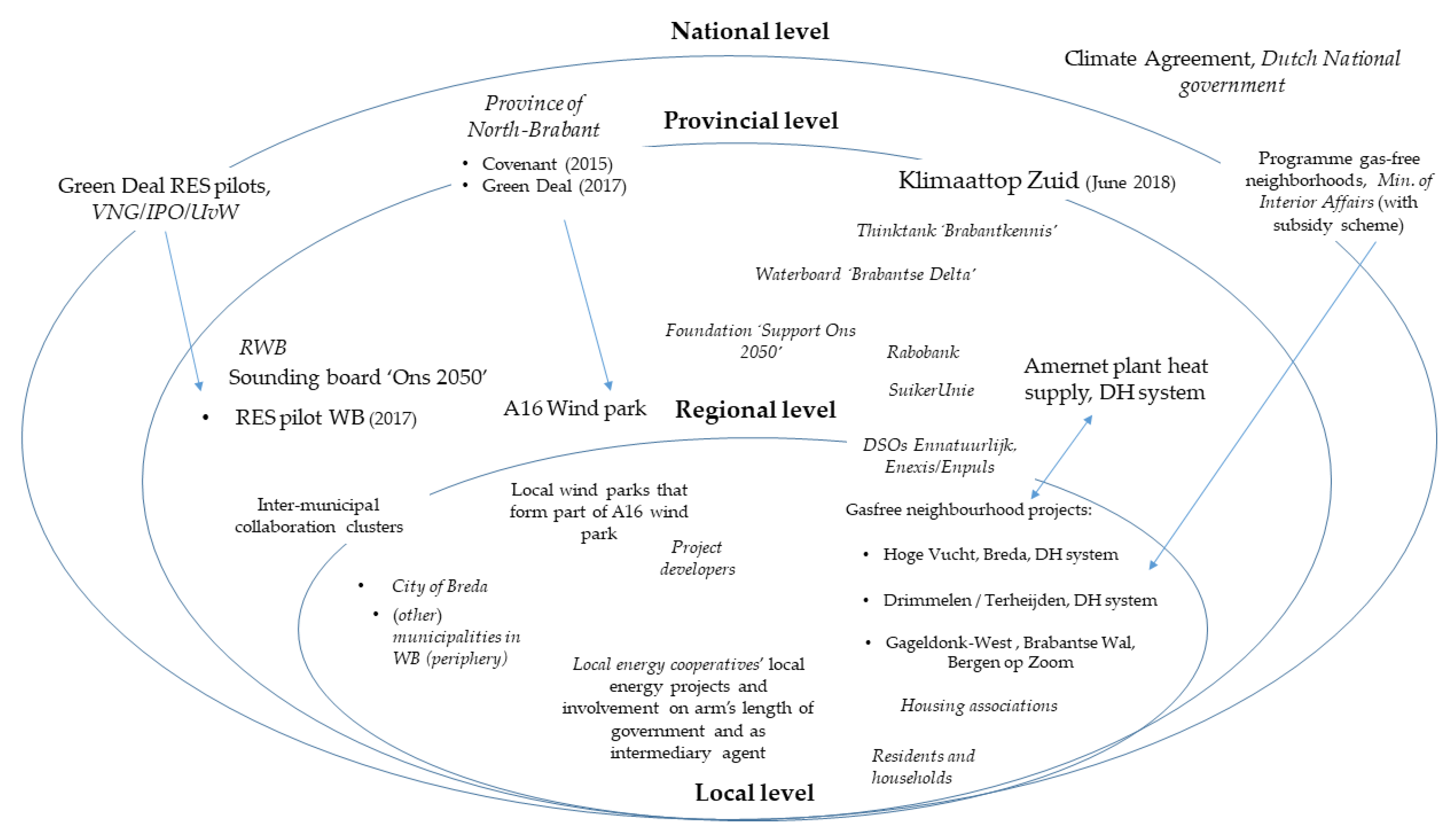

6.1. Case Study West-Brabant—Strategy Making, Key Events and Projects

6.1.1. Regional Energy Strategy Pilot West-Brabant

6.1.2. Amernet

6.1.3. Linking Amernet to City District Renovation Projects: The Case of Hoge Vucht, Breda

6.1.4. Windpark A16

6.1.5. Klimaattop Zuid

6.2. Results of the Reflective Regional Network Governance Analysis

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Engelenburg, B.; Maas, N. Regional Energy Transition (RET): How to improve the connection of praxis and theory? J. Technol. Archit. Environ. Behave. 2018, 1, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.J.; Huitema, D.; Hildén, M.; Van Asselt, H.; Rayner, T.J.; Schoenefeld, J.J.; Tosun, J.; Förster, J.; Boasson, E.L. Emergence of polycentric climate governance and its future prospects. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Späth, P.; Rohracher, H. The ‘eco-cities’ Freiburg and Graz: The social dynamics of pioneering urban energy and climate governance. In Cities and Low Carbon Transitions; Bulkeley, H., Broto, V.C., Hodson, M., Marvin, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013; pp. 88–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; Kern, K. Local Government and the Governing of Climate Change in Germany and the UK. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 2237–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, R.F.; Hoppe, T.; Brezet, H.; Blok, K. Good practices in local climate mitigation action by small and medium-sized cities; exploring meaning, implementation and linkage to actual lowering of carbon emissions in thirteen municipalities in The Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 630–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Van Der Vegt, A.; Stegmaier, P. Presenting a Framework to Analyze Local Climate Policy and Action in Small and Medium-Sized Cities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H. Cities and the Multilevel Governance of Global Climate Change. Glob. Gov. 2006, 12, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H. Cities and Climate Change; Informa UK Limited: Colchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; Betsill, M. Rethinking Sustainable Cities: Multilevel Governance and the ’Urban’ Politics of Climate Change. Environ. Polit. 2005, 14, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Assessing the Dutch Energy Transition Policy: How Does it Deal with Dilemmas of Managing Transitions? J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Van Der Brugge, R.; Taanman, M. Governance in the energy transition: Practice of transition management in The Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2008, 9, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balest, J.; Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Caimo, A. Sustainable energy governance in South Tyrol (Italy): A probabilistic bipartite network model. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenniches, S.; Worrell, E.; Fumagalli, E. Regional economic and environmental impacts of wind power developments: A case study of a German region. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattes, J.; Huber, A.; Koehrsen, J. Energy transitions in small-scale regions – What we can learn from a regional innovation systems perspective. Energy Policy 2015, 78, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, L.; Groenleer, M. The Regional Governance of Energy-Neutral Housing: Toward a Framework for Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warbroek, B.; Hoppe, T. Modes of Governing and Policy of Local and Regional Governments Supporting Local Low-Carbon Energy Initiatives; Exploring the Cases of the Dutch Regions of Overijssel and Fryslân. Sustain. 2017, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, L.; Campbell, S.; Wiseman, J. Regional Innovation Systems and Transformative Dynamics: Transitions in Coal Regions in Australia and Germany. In New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems—Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, P.; Uranga, M.G.; Etxebarria, G. Regional Systems of Innovation: An Evolutionary Perspective. Environ. Plan. A: Econ. Space 1998, 30, 1563–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Proximity and Innovation: A Critical Assessment. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemelmans-Videc, M.L.; Rist, R.C.; Vedung, E.O. (Eds.) Carrots, Sticks, and Sermons: Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Coenen, L.; Asheim, B.; Bugge, M.M.; Herstad, S.J. Advancing regional innovation systems: What does evolutionary economic geography bring to the policy table? Environ. Plan. C: Polit. Space 2017, 35, 600–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wäckerlin, N.; Hoppe, T.; Warnier, M.; De Jong, W.M. Comparing city image and brand identity in polycentric regions using network analysis. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, J.; Leguijt, C.; Ganzevles, J.; Van Est, R. Energietransitie begint in de regio: Rotterdam, Texel en Energy Valley onder de loep; Rathenau Instituut: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2009; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, S. Future governance of innovation policy in Europe—Three scenarios. Res. Policy 2001, 30, 953–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Translating Sustainabilities between Green Niches and Socio-Technical Regimes. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2007, 19, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, L.M.; Fischer, L.-B.; Newig, J.; Lang, D.J. Driving factors for the regional implementation of renewable energy - A multiple case study on the German energy transition. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Graf, A.; Warbroek, B.; Lammers, I.; Lepping, I. Local Governments Supporting Local Energy Initiatives: Lessons from the Best Practices of Saerbeck (Germany) and Lochem (The Netherlands). Sustainability 2015, 7, 1900–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R. Technology and the Transition to Environmental Sustainability—The Problem of Technological Regime Shifts. Futures 1994, 26, 1023–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Schot, J.; Hoogma, R. Regime shifts to sustainability through processes of niche formation: The approach of strategic niche management. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 1998, 10, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F. Processes and patterns in transitions and system innovations: Refining the co-evolutionary multi-level perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2005, 72, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management: New Mode of Governance for Sustainable Development; International Books: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. The practice of transition management: Examples and lessons from four distinct cases. Futures 2010, 42, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Hölscher, K.; Holman, I.P.; Pedde, S.; Jaeger, J.; Kok, K.; Harrison, P.A. Transition pathways to sustainability in greater than 2°C climate futures of Europe. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesler, T.; Hassler, M. Creating niches–The role of policy for the implementation of bioenergy village cooperatives in Germany. Energy Policy 2019, 124, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T.; Becker, S.; Naumann, M. Whose energy transition is it, anyway? Organisation and ownership of the Energiewende in villages, cities and regions. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 1547–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G.; Schakel, A.H.; Osterkatz, S.C.; Niedzwiecki, S.; Shair-Rosenfield, S. Measuring Regional Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, O.J.; Pierre, J. Exploring the Strategic Region: Rationality, Context, and Institutional Collective Action. Urban Aff. Rev. 2010, 46, 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, D.I. Regional Governance Networks: Filling In or Hollowing Out? Scand. Polit. Stud. 2015, 38, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogers, M.; Klok, P.J.; Denters, S.A.; Sanders, M.; Linnenbank, M. Effecten van regionaal bestuur voor gemeenten: Bestuursstructuur, samenwerkingsrelaties, democratische kwaliteit en bestuurlijke effectiviteit; Universiteit Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Klok, P.-J.; Denters, B.; Boogers, M.; Sanders, M. Intermunicipal Cooperation in The Netherlands: The Costs and the Effectiveness of Polycentric Regional Governance. Public Adm. Rev. 2018, 78, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevir, M. Governance: A Very Short Introduction; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Turrini, A.; Cristofoli, D.; Frosini, F.; Nasi, G. Networking literature about determinants of network effectiveness. Public Admin. 2010, 88, 528–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.-H. Governance and governance networks in Europe: An assessment of ten years of research on the theme. J. Public Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bueren, E.; Klijn, E.; Koppenjan, J. Dealing with wicked problems in networks: Analyzing an environmental debate from a network perspective. J. Public Admin. Res. Theory 2003, 13, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickert, W.J.M.; Klijn, E.-H.; Koppenjan, J.F.M. (Eds.) Managing Complex Networks: Strategies for the Public Sector; SAGE: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India, 1997; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn, E.-H.; Steijn, B.; Edelenbos, J. The Impact of Network Management on Outcomes in Governance Networks. Public Adm. 2010, 88, 1063–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.-H. Regels en sturing in netwerken: De invloed van netwerkregels op de herstructurering van naoorlogse wijken; Erasmus Universiteit: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Milward, H.B.; Provan, K.G.; Fish, A.; Isett, K.R.; Huang, K. Governance and Collaboration: An Evolutionary Study of Two Mental Health Networks. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2009, 20, i125–i141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruijn, H.; Ten Heuvelhof, E. Process Management: Why Project Management Fails in Complex Decision Making Processes; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Teisman, G.; Gerrits, L.J.C. The emergence of complexity in the art and science of governance. Complex. Gov. Netw. 2014, 1, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, L.J.; Meier, K.J. Public Management in Intergovernmental Networks: Matching Structural Networks and Managerial Networking. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2004, 14, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bueren, E. Greening Governance: An Evolutionary Approach to Policy Making for a Sustainable Built Environment; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.A. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sci. 1988, 21, 129–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. Sociol. Theory 1983, 1, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.-H.; Edelenbos, J.; Steijn, B. Trust in governance networks: Its impacts on outcomes. J. Admin. Soc. 2010, 42, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressers, H.; Bressers, N.; Kuks, S.; Larrue, C. The Governance Assessment Tool and Its Use. In Governance for Drought Resilience; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; p. 376. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, T.; Kooijman-van Dijk, A.; Arentsen, M. Governance of bio-energy: The case of Overijssel. In Proceedings of the Resilient Societies Conference, IGS, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 19–21 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, M.; Heldeweg, M.A.; Brunnekreef, A.V. Governance of Heat Grids: Towards a Governance Typology for Smart Heat Infrastructures. In Proceedings of the 2nd ESEIA International Conference on Smart and Green Transitions in Cities & Regions 2016, Graz, Austria, 4–6 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, G.; Hinderer, N. Situative governance and energy transitions in a spatial context: Case studies from Germany. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N.; McAdam, D. Toward a General Theory of Strategic Action Fields*. Sociol. Theory 2011, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Van Bueren, E. Guest editorial: Governing the challenges of climate change and energy transition in cities. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2015, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leck, H.; Simon, D. Fostering multiscalar collaboration and co-operation for effective governance of climate change adaptation. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1221–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedsworth, L.W.; Hanak, E. Climate policy at the local level: Insights from California. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, K.; Bulkeley, H. Cities, Europeanization and Multi-level Governance: Governing Climate Change through Transnational Municipal Networks. JCMS: J. Common Mark. Stud. 2009, 47, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Coenen, F. Creating an analytical framework for local sustainability performance: A Dutch Case Study. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D.; Salvia, M.; Heidrich, O.; Church, J.M.; Pietrapertosa, F.; De Gregorio-Hurtado, S.; D’Alonzo, V.; Foley, A.; Simões, S.G.; Lorencová, E.K.; et al. How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.P.; A Heldeweg, M.; Straatman, E.G.; Wempe, J.F. Energy policy by beauty contests: The legitimacy of interactive sustainability policies at regional levels of the regulatory state. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warbroek, B.; Hoppe, T.; Coenen, F.; Bressers, H. The Role of Intermediaries in Supporting Local Low-Carbon Energy Initiatives. Sustainabilty 2018, 10, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurs, R.; Schwencke, A.M. Lessen voor een Regionale Energietransitie: Slim schakelen; IPO, VNG, UVW, Rijksoverheid: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Boogers, M.; Klok, P.J. Praktijk van regionaal bestuur in Noord-Brabant; Universiteit Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Regiegroep Regionale Energiestrategie West-Brabant. Energiestrategie voor de regio West-Brabant: Ons2050; RWB: Etten-Leur, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Elzenga, H.; Schwencke, A.; Hoorn, A.V. Het handelingsperspectief van gemeenten in de energietransitie naar een duurzame warmte—en elektriciteitsvoorziening; PBL: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2017; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Schwencke, A.M. Lokale Energie Monitor 2019; HIER opgewekt/RVO: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–195. [Google Scholar]

- Miedema, M. Naar een regionale energietransitie; Analyse van de samenwerking aan de verduurzaming van de energievoorziening van de woningvoorraad in West-Brabant; EUR/TU Delft: Rotterdam/Delft, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–125. [Google Scholar]

- Niemann, L.; Hoppe, T.; Coenen, F. On the Benefits of Using Process Indicators in Local Sustainability Monitoring: Lessons from a Dutch Municipal Ranking (1999–2014). Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; de Vries, G. Social Innovation and the Energy Transition. Sustainability 2019, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Structural characteristics of the regional network | Size |

| Degree of complexity | |

| Polycentric decision-making arenas | |

| Cohesion | |

| Presence of clusters, sub-networks and coalitions | |

| (Weak) ties to other networks | |

| Regional network composition | Actor membership and heterogeneity |

| Scope (multi-level, multi-sector) | |

| Involvement of regime outsiders | |

| Interaction with incumbents | |

| Interaction of subsystems | |

| History of network actor interaction | |

| Culture of interaction | |

| Actor characteristics | Motivation and goals |

| Cognition | |

| Access to and ownership of resources (e.g., competences, knowledge, capacities, ownership of critical infrastructure) | |

| Dependencies, such as need of inter-municipal collaboration | |

| Intra-organizational characteristics (organizational culture, esprit de corps, adaptive management, bureaucracy) | |

| Regional network governance | Agenda (goal-setting, planning and policy) of the regional network as a collective |

| Legitimacy, commitment and compliance | |

| Rules of the game (institutional rules) | |

| Leadership and control | |

| Presence of a regional network organization | |

| Experimenting | |

| Arena of arenas with forum (’meta governance’) | |

| Formal mandate to act | |

| Process- and network management | |

| Establishment of a common language | |

| Proximity | |

| Policy instruments and ’mixes’ | |

| Membership of issue networks | |

| External factors | Economic circumstances |

| Context-specific characteristics of the region (like presence of natural resources or industry) | |

| Formal status of the region | |

| Region’s status as embedded in governance structures | |

| Regional politics and policy priorities | |

| Presence of energy plants and infrastructures in the region |

| Name of Organization | Type of Organization | Function of Interviewee | Date of Interview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ons 2050 | Regional energy transition support organization | Chair and member of executive organization | 23 May 2018 and 1 June 2018 |

| Rabobank | Bank | Director | 23 May 2018 |

| Wonen Breburg | Housing association | Purchasing manager, network manager, and advisor sustainability | 25 May 2018 and 21 June 2018 |

| Vrins Advies | Advisor | Energy and neighborhood visions advisor | 28 May 2018 |

| Alwel | Housing association | Advisor rental affairs and sustainability | 29 May 2018 |

| Bergen op Zoom | Municipality | Civil servant sustainability policy | 30 May 2018 |

| Energiek Brabantse Wal | Community energy cooperative | Chair | 30 May 2018 |

| Energieloket West-Brabant | Executive organization in local energy policy | Self-employed entrepreneur | 1 June 2018 |

| Energiecoöperatie Halderberge | Community energy cooperative | Chair | 1 June 2018 |

| Regio West-Brabant (RWB) | Regional governance organization | Program manager spatial affairs | 5 June 2018 |

| Gemeente Steenbergen | Municipality | Alderman and policy officer | 6 June 2018 |

| AM ISearch | Consultancy | Advisor sustainability | 6 June 2018 |

| Enexis/Enpuls | DSO with business unit on energy transition | Strategic advisor energy affairs | 11 June 2018 |

| Ennatuurlijk | DSO heating grid | Account manager | 13 June 2018 |

| Bredase Energie Coöperatie (BRES) | Community energy cooperative | Chair | 13 June 2018 |

| Province of North-Brabant | Provincial government | Policy officer | 14 June 2018 |

| Gemeente Breda | Municipality | Policy officer of DH systems | 15 June 2018 and 21 June 2019 |

| Waterschap Brabantse Delta | Water Board | Senior policy officer | 15 June 2018 |

| Woningstichting Stadlander | Housing association | Sustainability manager | 26 June 2018 |

| Theoretical Factors of the Analytical Framework | Presence in WB Case | Influence on RET in WB Case |

|---|---|---|

| Regional Network Composition | ||

| Actor membership and heterogeneity | Moderate, but increased | Fairly positive |

| Scope (multi-level, multi-sector) | Moderate, but increased | Moderate |

| Involvement of regime outsiders | At first rather low, but increased | Fairly positive |

| Interaction with incumbents | Fairly strong | Moderate |

| Interaction of subsystems | Relatively weak | Fairly negative |

| History of network actor interaction | Strong | Moderate |

| Culture of interaction | Fairly strong | Moderate |

| Actor Characteristics | ||

| Motivation and goals | Moderate, but decreased | Negative |

| Cognition | Relatively weak | Negative |

| Access to and ownership of resources (e.g., competences, knowledge, capacities, ownership of critical infrastructure) | Relatively weak | Negative |

| Dependencies, such as need of inter-municipal collaboration | Moderate | Moderate |

| Intra-organizational characteristics (organizational culture, esprit de corps, adaptive management, bureaucracy) | Negative | Negative |

| Structural Characteristics of the Regional Network | ||

| Size | Fairly large | Fairly negative |

| Degree of complexity | Fairly complex | Negative |

| Polycentricity | Fairly complex | Moderate |

| Cohesion | Fairly strong | Moderate |

| Presence of clusters, sub-networks and coalitions | Presence of a fair amount of clusters | Moderate |

| Weak ties to other networks | Fairly strong | Fairly positive |

| Regional Network Governance | ||

| Agenda (goal-setting, planning and policy) of the regional network as a collective | Progressive, but decreased | Negative |

| Legitimacy, commitment and compliance | Fairly poor | Negative |

| Rules of the game (institutional rules) | High degree of institutions present | Fairly negative |

| Leadership and control | Moderate, but decreased | Fairly negative |

| Presence of a regional network organization | Moderate, but decreased | Fairly negative |

| Experimenting | Fair degree of experiments undertaken | Fairly positive |

| Arena of arenas with forum (‘meta governance’) | Poorly developed | Negative |

| Formal mandate to act | Absent | Negative |

| Process- and network management | Present at local level, ceased to exist at the regional level | Fairly negative |

| Establishment of a common language | Poorly developed | Negative |

| Proximity | Perceived as high proximity | Fairly negative |

| Policy instruments and ‘mixes’ | High degree of third generation instruments used. Poor use of economic instruments | Fairly negative |

| Membership of issue networks | Fair amount of memberships | Fairly positive |

| External Factors | ||

| Economic circumstances | Positive | Moderate |

| Context-specific characteristics of the region (like presence of natural resources or industry) | Fairly strong | Positive |

| Formal status of the region | No official status to Regional Energy Strategy | Negative |

| Region’s status as embedded in governance structures | Relatively poor | Fairly negative |

| Regional political and policy priorities | Moderate, but decreased | Negative |

| Presence of energy plants and infrastructures in the region (e.g., for use of residual heat) | Present | Positive |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoppe, T.; Miedema, M. A Governance Approach to Regional Energy Transition: Meaning, Conceptualization and Practice. Sustainability 2020, 12, 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030915

Hoppe T, Miedema M. A Governance Approach to Regional Energy Transition: Meaning, Conceptualization and Practice. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030915

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoppe, Thomas, and Michiel Miedema. 2020. "A Governance Approach to Regional Energy Transition: Meaning, Conceptualization and Practice" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030915

APA StyleHoppe, T., & Miedema, M. (2020). A Governance Approach to Regional Energy Transition: Meaning, Conceptualization and Practice. Sustainability, 12(3), 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030915