The Host Community and Its Role in Sports Tourism—Exploring an Emerging Research Field

Abstract

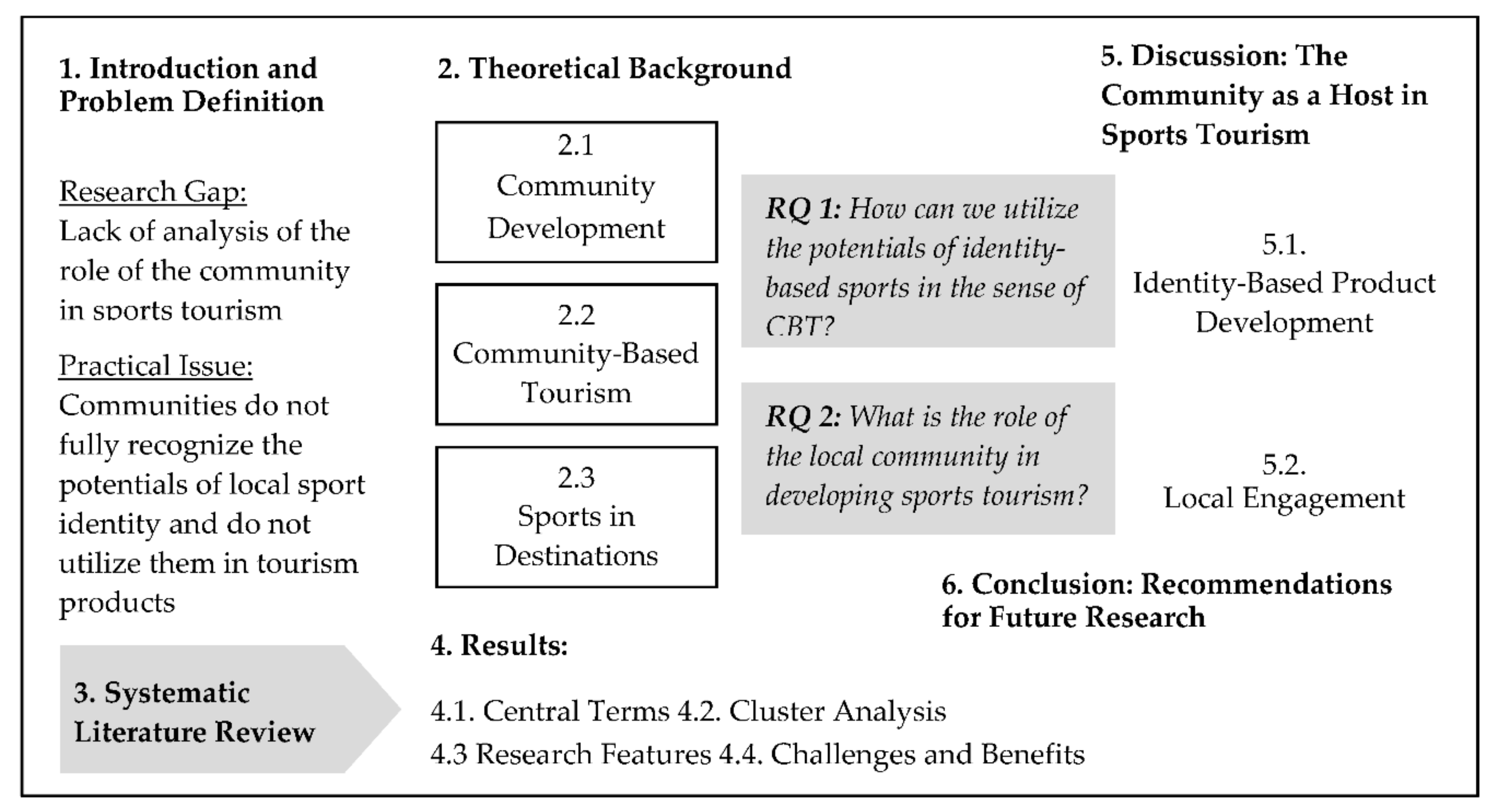

1. Introduction and Problem Definition

2. Theoretical Background: Sports Tourism in the Context of Community Development

2.1. Community and Community Development

2.2. Community-Based Tourism as a Development Approach

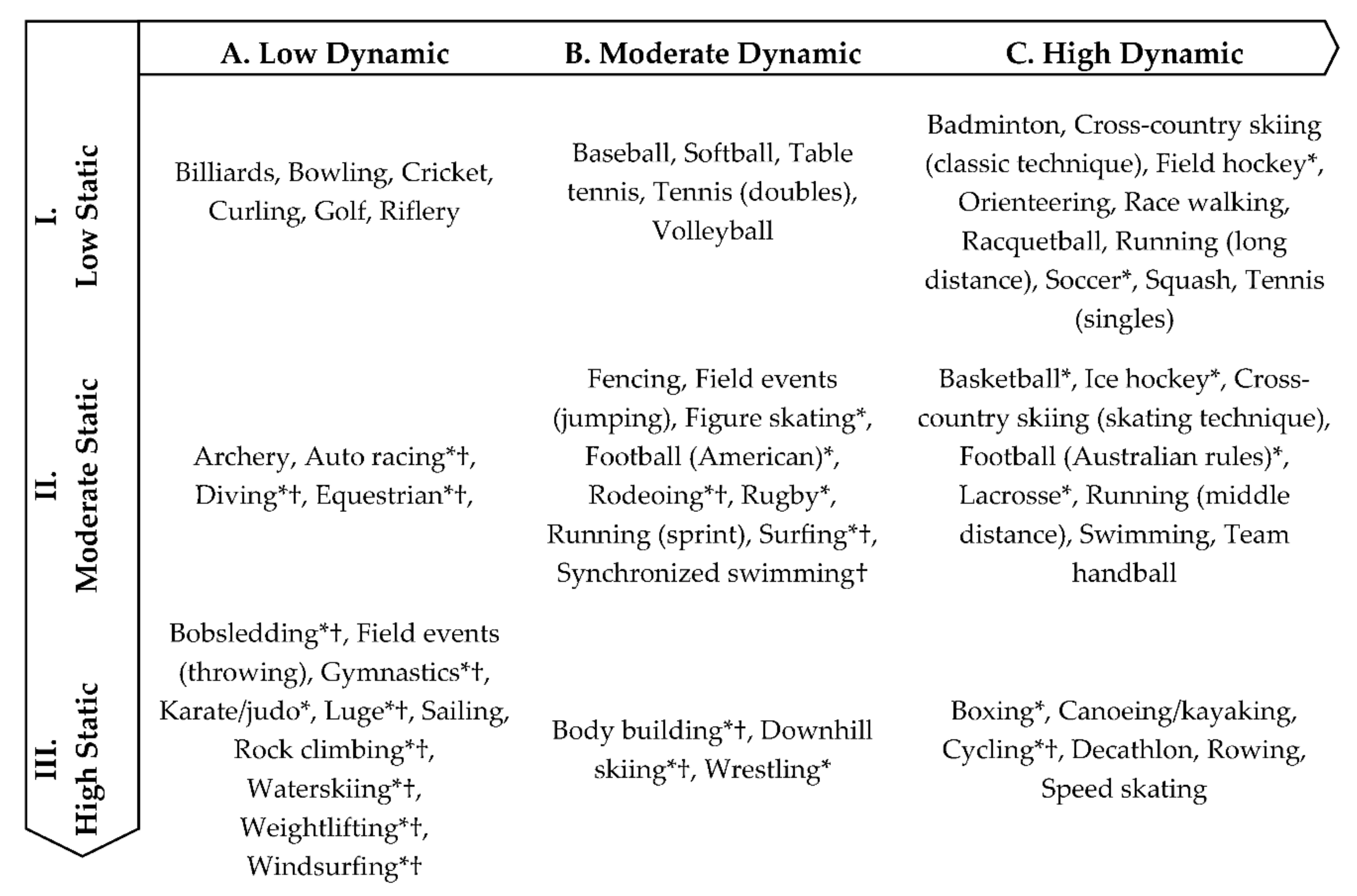

2.3. Sports Tourism and Its Relevance for Local Development

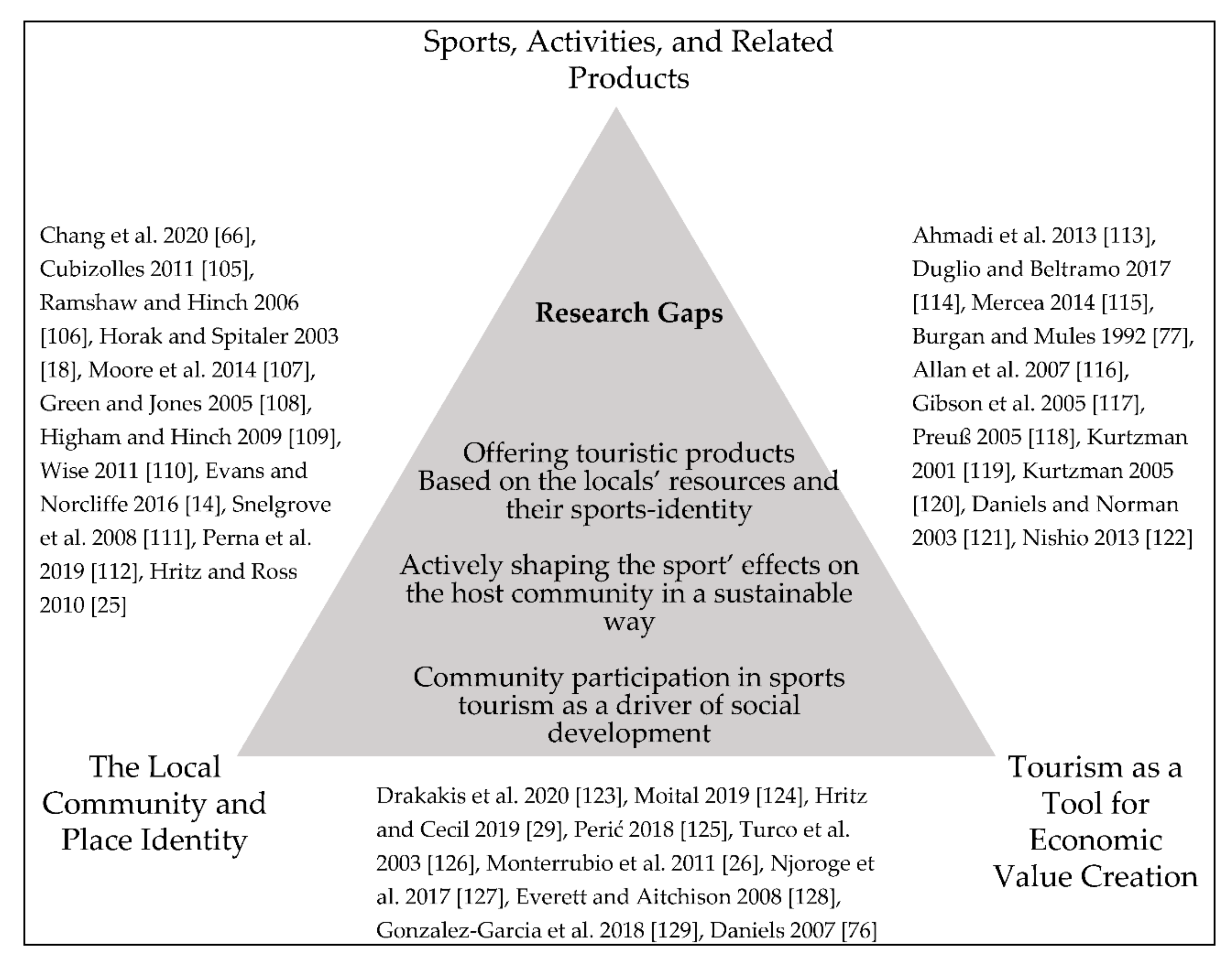

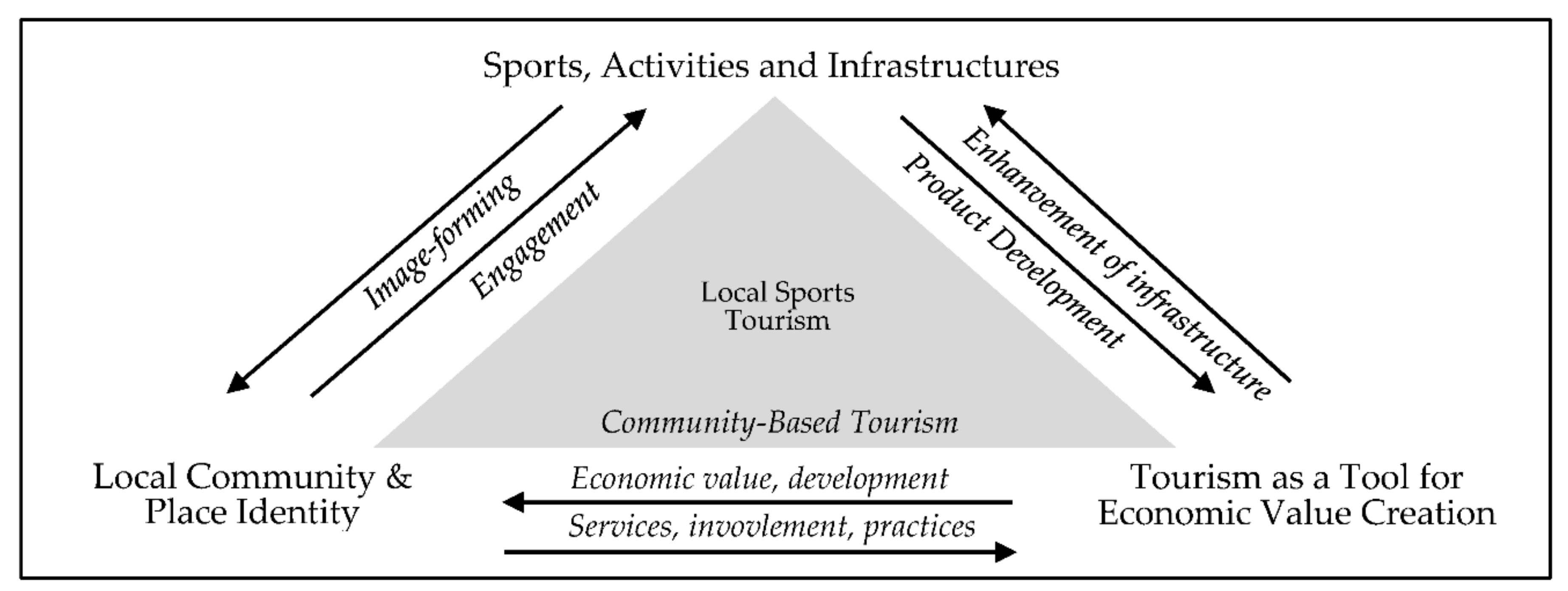

2.4. Deriving a Conceptual Framework for Local Sports Tourism

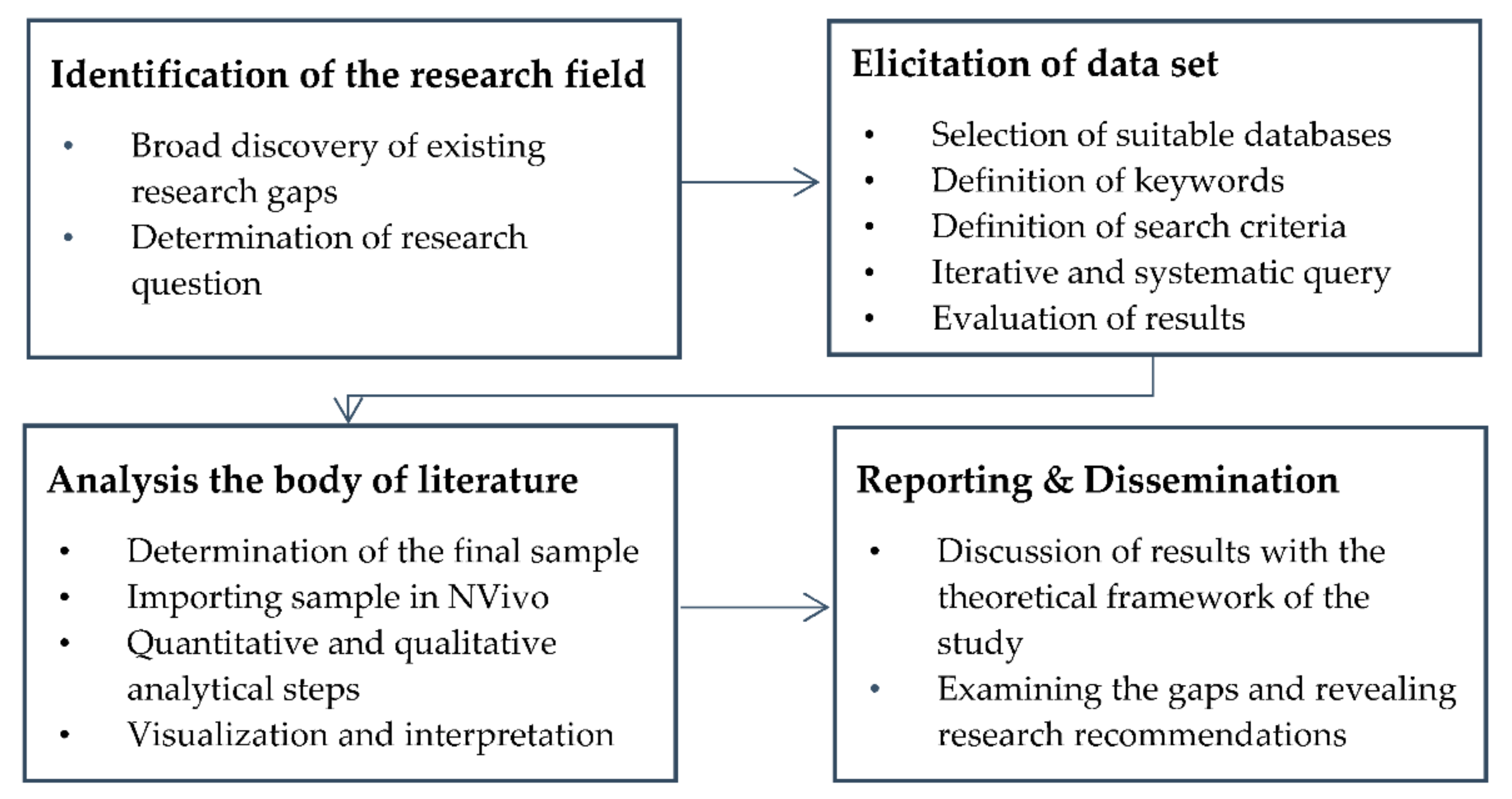

3. Methodology: Systematic Literature Review

- ‘Tourism’ AND ‘Community’ AND ‘Sport’

- ‘Tourism’ AND ‘Development’ AND ‘Sport’

- ‘Destination’ AND ‘Sport’ AND ‘Tourism’.

4. Results: Framing the Research Field

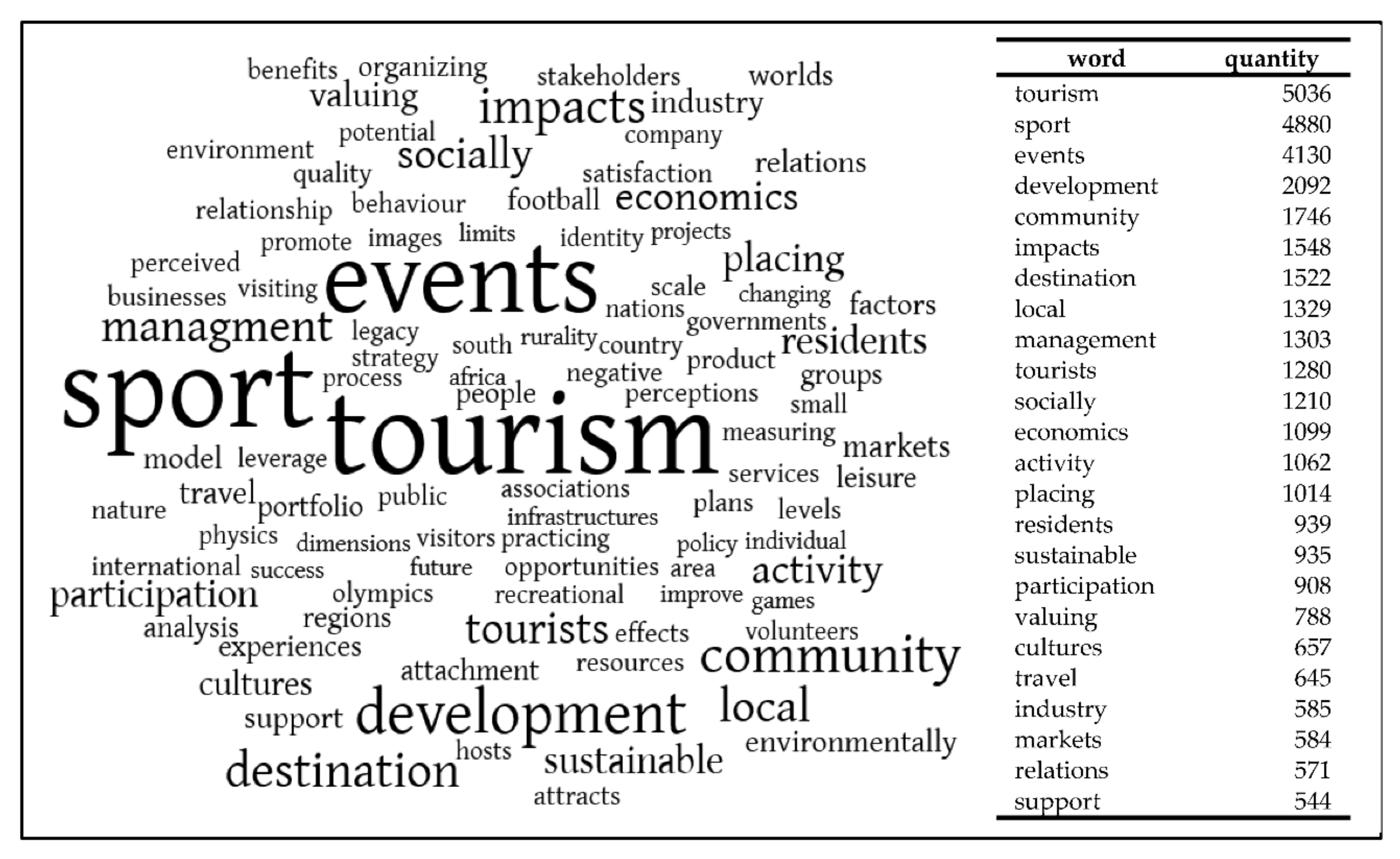

4.1. Word Cloud: Visualizing the Central Terms

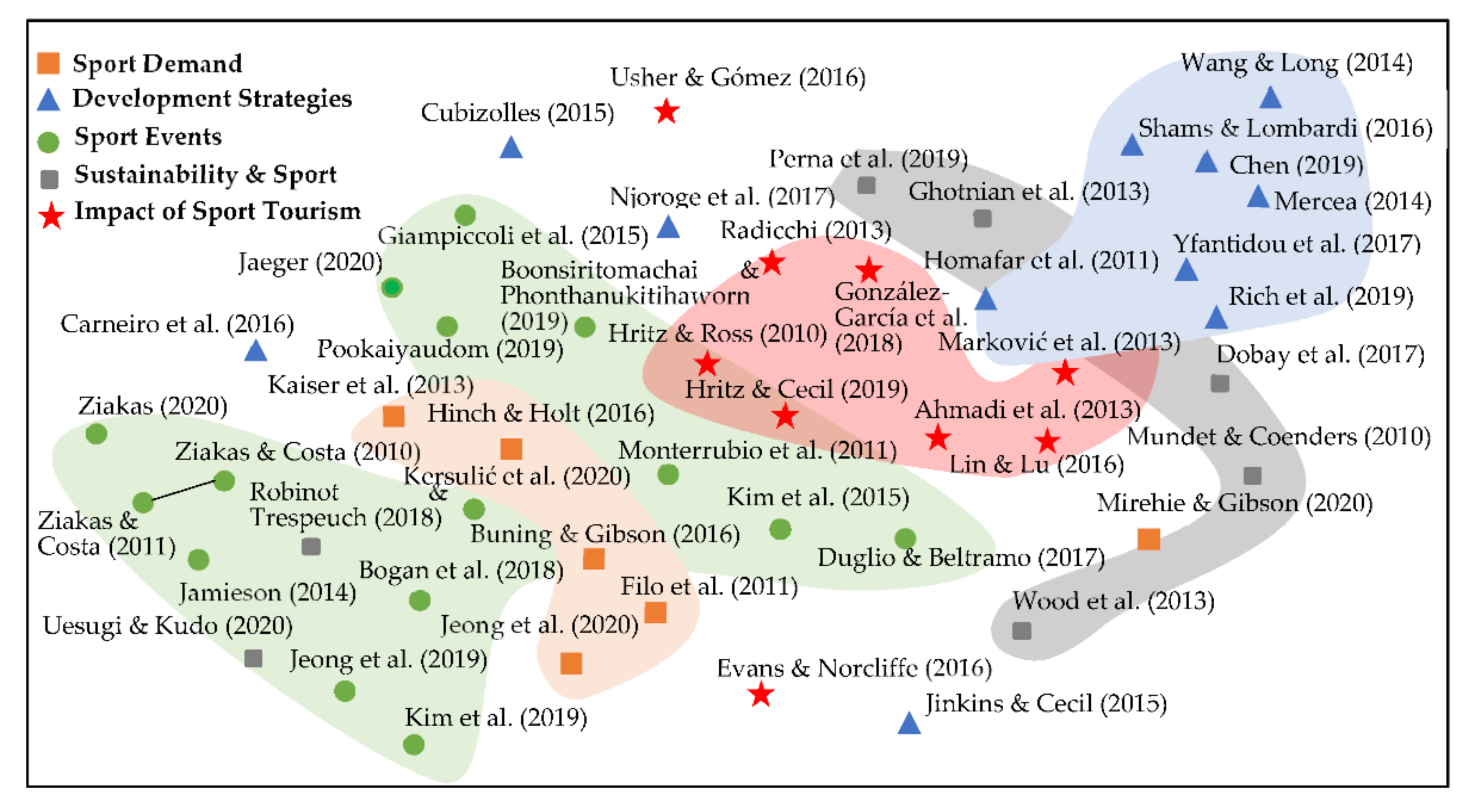

4.2. Cluster Analysis: Thematic Proximity

4.3. Research Features of Articles

4.4. Challenges and Benefits of Sports Tourism in/for Local Communities

5. Discussion: The Community as a Host in Sports Tourism

5.1. Approaching Identity-Based Product Development

5.2. Local Engagement as a Success Factor

- Accommodation suppliers [29]

6. Conclusions: Recommendations for Future Research

- Multidisciplinarity: The analysis of sports tourism should be expanded from an event focus towards sustainability issues and the local community. This also requires bridging development approaches, such as CBT, with the features of sports. The cultural theories and theories around “Sport-for-Development” offer a suitable perspective as they consider sports to “facilitate personal development and social change by embracing non-traditional sport management practices through an interdisciplinary framework, blending sport with cultural enrichment” [201] (p. 313). The sport-for-development stream discusses issues regarding the positive impacts on society and the economy from sports activities. What lacks in the discussions of SFD are tourism-based perspectives and development opportunities. This provides a legitimate starting point for future analyses to penetrate the gap between SFD aspects and CBT potentials.

- The diversity of sports: Research should address different sports activities and their impacts on the local community. This also includes small-scale sports events and non-event-related activities, especially those that are practiced by locals. These potentially unpopular activities can be of great interest, as they are deeply rooted in communities’ identities. Thus, these sports open space for dealing with tourism.

- Sustainability-orientation: There is increasing awareness of the importance of sustainability in sports tourism. Research in this field is, nevertheless, still limited and is mostly confined to specific areas such as mega-events [30].

- Methods should concentrate on in-depth case studies to illustrate local challenges and benefits. The assessment of impacts on local areas is also of relevance here.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. The Impact of COVID-19 on Sport, Physical Activity and Well-Being and Its Effects on Social Development|DISD. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/2020/05/covid-19-sport/ (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Giove, G. Studie Bestätigt: Laufboom durch Corona. Achilles Running. 3 June 2020. Available online: https://www.achilles-running.de/welttag-des-laufens-studie-zeigt-laufboom-durch-corona/ (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Catuogno, C. Im Park Statt in New York. Süddeutsche Zeitung. 25 June 2020. Available online: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/sport/kommentar-im-park-statt-in-new-york-1.4948077 (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Ryan, T.J. Is The COVID-19 Running Boom Sustainable? SGB Media Online. 27 October 2020. Available online: https://sgbonline.com/is-the-covid-19-running-boom-sustainable/ (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Vetter, C. Gescheiterte Olympia-Bewerbung von Tirol: Winterspiele Machen Keinen Sinn Mehr! Tagesspiegel. Available online: https://www.tagesspiegel.de/sport/gescheiterte-olympia-bewerbung-von-tirol-winterspiele-machen-keinen-sinn-mehr/20459798.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Szymanski, M.; Frank, M. Hilfe für die “Bayerischen Freunde”. Süddeutsche Zeitung. 29 July 2010. Available online: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/bayern/olympia-bewerbung-hilfe-fuer-die-bayerischen-freunde-1.979602 (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Hecker, A. Olympia Vereist. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 16 October 2017. Available online: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/sport/sportpolitik/innsbruck-sagt-nein-olympia-vereist-15249244.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Skinner, J.; Woolcock, G.; Milroy, A. SDP and social capital. In Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace; Collison, H., Darnell, S.C., Giulianotti, R., Howe, P.D., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 296–307. ISBN 9781315455174. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, A.M. SDP and sport psychology. In Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace; Collison, H., Darnell, S.C., Giulianotti, R., Howe, P.D., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 230–240. ISBN 9781315455174. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, H.J.; Kaplanidou, K.; Kang, S.J. Small-scale event sport tourism: A case study in sustainable tourism. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E.A.; Kulczycki, C.; Moghimehfar, F. Factors effecting destination and event loyalty: Examining the sustainability of a recurrent small-scale running event at Banff National Park. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Gibson, H.J. Predicting Behavioral Intentions of Active Event Sport Tourists: The Case of a Small-scale Recurring Sports Event. J. Sport Tour. 2010, 15, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechlaner, H.; Nordhorn, C.; Poppe, X. Being a guest—Perspectives of an extended hospitality approach. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.; Norcliffe, G. Local identities in a global game: The social production of football space in Liverpool. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinkins, L.; Cecil, A.K. A Shift in Community Engagement Models: A Case Study of Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and the Indianapolis Business Community. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2015, 16, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürtjes, O. Football and its continuity as a classless mass phenomenon in Germany and England: Rethinking the bourgeoisification of football crowds. Soccer Soc. 2014, 17, 588–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.D. Everyday nationalism and international hockey: Contesting Canadian national identity. Nations Natl. 2016, 23, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, R.; Spitaler, G. Sport Space and National Identity. Am. Behav. Sci. 2003, 46, 1506–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Boston Globe. Getting up to Speed in the Kenyan Village of Iten. Available online: https://www.boston.com/travel/travel/2017/12/21/getting-up-to-speed-in-the-kenyan-village-of-iten (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Perić, M.; Dragičević, D.; Škorić, S. Determinants of active sport event tourists’ expenditure—The case of mountain bikers and trail runners. J. Sport Tour. 2019, 23, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Altitude Training Centre. About HATC. Available online: https://hatc-iten.com/about/ (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. 2017 Is the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/archive/global/press-release/2017-01-03/2017-international-year-sustainable-tourism-development (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Sustainable Development Goals—SDGs—The United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Jamieson, N. Sport Tourism Events as Community Builders—How Social Capital Helps the “Locals” Cope. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2014, 15, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hritz, N.; Ross, C. The Perceived Impacts of Sport Tourism: An Urban Host Community Perspective. J. Sport Manag. 2010, 24, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrubio, J.C.; Ramírez, O.; Ortiz, J.C. Host community attitudes towards sport tourism events: Social impacts of the 2011 Pan American Games. E Rev. Tour. Res. 2011, 9, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, H. Sport Tourism: Concepts and Theories. An Introduction. Sport Soc. 2006, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, S.; Ziakas, V.; Sparvero, E. Linking corporate social responsibility in sport with community development: An added source of community value. Sport Soc. 2016, 20, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hritz, N.; Cecil, A. Small business owner’s perception of the value and impacts of sport tourism on a destination. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2019, 20, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M.J.; Breda, Z.; Cordeiro, C. Sports tourism development and destination sustainability: The case of the coastal area of the Aveiro region, Portugal. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakas, V.; Costa, C.A. ‘Between Theatre and Sport’ in a Rural Event: Evolving Unity and Community Development from the Inside-Out. J. Sport Tour. 2010, 15, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.K.; Wood, J. (Eds.) The Making of a Cultural Landscape: The Englisch Lake District as Tourist Destination, 1750–2010; First iussed in paperback; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781138246256. [Google Scholar]

- Billings, J.R. Community development: A critical review of approaches to evaluation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Brennan, M.A. Conceptualizing community development in the twenty-first century. Community Dev. 2012, 43, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.J. Community Development and Social Development. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2016, 26, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M. A Conceptualisation of Alternative Forms of Tourism in Relation to Community Development. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.; Servon, L.J. CDCs and the Changing Context for Urban Community Development: A Review of the Field and the Environment. Community Dev. 2009, 37, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, D.V.; Robinson, K.L.; Allen, I.; Christy, R.D. Essential Forms of Capital for Sustainable Community Development. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 85, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flagestad, A.; Hope, C.A. Strategic success in winter sports destinations: A sustainable value creation perspective. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M.; Pechlaner, H.; Pichler, S. The practice of destination governance: A comparative analysis of key dimensions and underlying concepts. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2017, 3, 18–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kagermeier, A.; Amzil, L.; Elfasskaoui, B. The transition of governance approaches to rural tourism in Southern Morocco. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 40–62. [Google Scholar]

- Herntrei, M. Wettbewerbsfähigkeit von Tourismusdestinationen. Bürgerbeteiligung als Erfolgsfaktor? Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorello, A.; Bo, D. Community-Based Ecotourism to Meet the New Tourist’s Expectations: An Exploratory Study. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 758–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Pechlaner, H. Alternative Product Development as Strategy towards Sustainability in Tourism: The Case of Lanzarote. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naku, D.W.C.; Afrane, S. Local Community Development and the Participatory Planning Approach: A Review of Theory and Practice. Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 5, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, K.A.; Sulle, E.B. Tourism in Maasai communities: A chance to improve livelihoods? J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 935–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holladay, P.J.; Powell, R.B. Resident perceptions of social–ecological resilience and the sustainability of community-based tourism development in the Commonwealth of Dominica. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1188–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M.; Jugmohan, S. Are ‘Albergo Diffuso’ and community-based tourism the answers to community development in South Africa? Dev. S. Afr. 2016, 33, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, E. A Community-Based Tourism Model: Its Conception and Use. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Ali, A.; Galaski, K. Mobilizing knowledge: Determining key elements for success and pitfalls in developing community-based tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 21, 1547–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Local tourism awareness: Community views in Katutura and King Nehale Conservancy, Namibia. Dev. S. Afr. 2010, 27, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Tourism for Development: Empowering Communities; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Snyman, S.L. The role of tourism employment in poverty reduction and community perceptions of conservation and tourism in southern Africa. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Lindo, P.; Vanderschaeghe, M. Can community-based tourism contribute to development and poverty alleviation? Lessons from Nicaragua. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 725–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantsperger, M.; Thees, H.; Eckert, C. Local Participation in Tourism Development—Roles of Non-Tourism Related Residents of the Alpine Destination Bad Reichenhall. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggers, A.; Grabowski, S.; Wearing, S.; Chatterton, P.; Schweinsberg, S. Exploring outcomes of community-based tourism on the Kokoda Track, Papua New Guinea: A longitudinal study of Participatory Rural Appraisal techniques. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.B.; Prideaux, B. A management model to assist local communities developing community-based tourism ventures: A case study from the Brazilian Amazon. J. Ecotour. 2017, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocharungsat, P. Community-based tourism in Asia. In Building Community Capacity for Tourism Development; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A. Is community-based ecotourism a good use of biodiversity conservation funds? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, G. An overview of contemporary tourism development in Brazil. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 12, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebele, L.S. Community-based tourism ventures, benefits and challenges: Khama Rhino Sanctuary Trust, Central District, Botswana. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonsiritomachai, W.; Phonthanukitithaworn, C. Residents’ Support for Sports Events Tourism Development in Beach City: The Role of Community’s Participation and Tourism Impacts. SAGE Open 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Lee, S.; Nauright, J. Destination South Africa: Comparing global sports mega-events and recurring localised sports events in South Africa for tourism and economic development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 18, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, M.; Brown, K.; Hoye, R. Sport, community involvement and social support. Sport Soc. 2013, 17, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-X.; Choong, Y.-O.; Ng, L.-P. Local residents’ support for sport tourism development: The moderating effect of tourism dependency. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 24, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinch, T.; Higham, J.E.S. Sport Tourism Development, 2nd ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011; ISBN 9781845411954. [Google Scholar]

- Schlemmer, P.; Barth, M.; Schnitzer, M. Research note sport tourism versus event tourism: Considerations on a necessary distinction and integration. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2020, 21, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, M. Social and Associative Sports Tourism in France: The Glénans and the National Union of Outdoor Sports Centres (UCPA). Int. J. Hist. Sport 2020, 37, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejón-Guardia, F.; Alemany-Hormaeche, M.; García-Sastre, M.A. Ibiza dances to the rhythm of pedals: The motivations of mountain biking tourists competing in sporting events. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, L. A wider role for sport: Community sports hubs and urban regeneration. Sport Soc. 2016, 19, 1537–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenbach, M.; Tuppen, J. The concept of localised outdoor sports tourist systems: Its application to Ardèche in south-east France. J. Sport Tour. 2017, 21, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godtman Kling, K.; Fredman, P.; Wall-Reinius, S. Trails for tourism and outdoor recreation: A systematic literature review. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2017, 65, 488–508. [Google Scholar]

- Uesugi, A.; Kudo, Y. The relationship between outdoor sport participants’ place attachment and pro-environment behaviour in natural areas of Japan for developing sustainable outdoor sport tourism. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2020, 17, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, M.; Vitezić, V.; Badurina, J. Đurkin Business models for active outdoor sport event tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M.J. Central place theory and sport tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgan, B.; Mules, T. Economic impact of sporting events. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mules, T.; Dwyer, L. Public Sector Support for Sport Tourism Events: The Role of Cost-benefit Analysis. Sport Soc. 2005, 8, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, J. Predicting the Costs and Benefits of Mega-Sporting Events: Misjudgement of Olympic Proportions? Econ. Aff. 2009, 29, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SkiWelt. Austria’s Greatest Mountain Experience: Summer Lift Operations Wilder Kaiser—Brixental. Available online: https://www.skiwelt.at/en/unique-summer-experiences-in-tyrol.html (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Stadtwerke München GmbH. Olympia-Schwimmhalle|Hallenbad, Sauna, Fitness. Available online: https://www.swm.de/baeder/schwimmen-sauna/olympia-schwimmhalle (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Nuerburgring.de. Opening Hours. Available online: https://www.nuerburgring.de/en/fans-info/info/opening-hours.html (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- rafting-canyoning.de. Canyoning in Tyrol. Available online: https://www.rafting-canyoning.de/en/canyoning.htm (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Bayerischer Wald. Kletterfelsen und -Hallen. Available online: https://www.bayerischer-wald.de/Urlaubsthemen/Aktiv-Abenteuer/Hoehen-Erlebnis/Kletterfelsen-und-hallen (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Eurobike. Guided Cycle Tours: Group Tour with Tour Guide. Available online: https://www.eurobike.at/en/cycling-holidays/tour-type/guided-cycle-tours (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Davies, L.E. Using sports infrastructure to deliver economic and social change: Lessons for London beyond 2012. Local Econ. 2011, 26, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, A.; Digance, J. Exploiting Unused Capacity. J. Conv. Exhib. Manag. 2002, 3, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacClancy, J. Sport, Identity, and Ethnicity; Bloomsbury Publishing PLC: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lüschen, G. The Interdependence of Sport and Culture. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 1967, 2, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Lacrosse. GAISF Definition of Sport. Available online: https://worldlacrosse.sport/about-world-lacrosse/gaisf/ (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Zillertal Tourismus GmbH. Activities in Zillertal in Tirol. Available online: https://en.zillertal.at/en/tips.html (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Turismo de Portugal. Nazaré. Available online: https://www.visitportugal.com/en/node/73770 (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Pacific Tourism Organisation. Fishing Tourism in Pacific Island Countries. Available online: http://southpacificspecialist.org/fishing-tourism-in-pacific-island-countries/ (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Cook Island Tourism Corporation. Fishing|Cook Islands. Available online: https://cookislands.travel/experiences/water/fishing (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- American-Samoa. Fisheries|American-Samoa. Available online: https://www.americansamoa.gov/things-to-do-in-american-samoa (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Namotu Island Fiji. Fishing in Fiji: The Best Fishing Spots and Types of Fish You Can Catch!|Namotu Island Fiji. Available online: https://www.namotuislandfiji.com/blog/fishing-in-fiji-the-best-fishing-spots-and-types-of-fish-you-can-catch/ (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Eifel Tourismus GmbH. Top 10 Ausflugsziele Eifel. Available online: https://www.eifel.info/ausflugsziele/top-10-ausflugsziele-eifel (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Eventimpresents GmbH & Co., KG. Rock am Ring 2021. Available online: https://www.rock-am-ring.com/ (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Tourismus in den Ardennen. Découvrir Die Rennstrecke von Spa-Francorchamps—Tourismus in den Ardennen. Available online: https://www.visitardenne.com/de/das-beste-der-ardennen/ardenner-highlights/die-rennstrecke-von-spa-francorchamps (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Mitchell, J.H.; Haskell, W.L.; Raven, P.B. Classification of sports. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994, 24, 864–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M. Sports Tourism Theory and Method—Concepts, Issues and Epistemologies. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2005, 5, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicchi, E. Tourism and Sport: Strategic Synergies to Enhance the Sustainable Development of a Local Context. Phys. Cult. Sport. Stud. Res. 2013, 57, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonts, M.; Atherley, K. Competitive sport and the construction of place identity in rural Australia. Sport Soc. 2010, 13, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, J.; Verweel, P. Participation in sport: Bonding and bridging as identity work. Sport Soc. 2009, 12, 1206–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubizolles, S. Marketing Identity and Place: The Case of the Stellenbosch Kayamandi Economic Corridor Before the 2010 World Cup in South Africa. J. Sport Tour. 2011, 16, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramshaw, G.; Hinch, T. Place Identity and Sport Tourism: The Case of the Heritage Classic Ice Hockey Event. Curr. Issues Tour. 2006, 9, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.; Richardson, M.; Corkill, C. Identity in the “Road Racing Capital of the World”: Heritage, geography and contested spaces. J. Heritage Tour. 2014, 9, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.C.; Jones, I. Serious Leisure, Social Identity and Sport Tourism. Sport Soc. 2006, 8, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.; Hinch, T. Sport and Tourism. Sport Tour. 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, N. Transcending imaginations through football participation and narratives of the other: Haitian national identity in the Dominican Republic. J. Sport Tour. 2011, 16, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelgrove, R.; Taks, M.; Chalip, L.; Green, B.C. How Visitors and Locals at a Sport Event Differ in Motives and Identity. J. Sport Tour. 2008, 13, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Perna, F.; Custódio, M.J.; Oliveira, V. Local Communities and Sport Activities Expenditures and Image: Residents’ Role in Sustainable Tourism and Recreation. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2019, 9, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Moeenfard, M.R.; Tabaeeban, S.A. The impacts of sport tourism development in Kish Island. J. Am. Sci. 2013, 9, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Duglio, S.; Beltramo, R. Estimating the Economic Impacts of a Small-Scale Sport Tourism Event: The Case of the Italo-Swiss Mountain Trail CollonTrek. Sustainability 2017, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercea, T.I. Strategies for tourism development in Arges through sports and recreational activities. In Annals of “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati-Fascicle XV: Physical Education and Sport Management; Galati University Press: Galati, Romania, 2014; pp. 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, G.; Dunlop, S.; Swales, J.K. The Economic Impact of Regular Season Sporting Competitions: The Glasgow Old Firm Football Spectators as Sports Tourists. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 63–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.; McIntyre, S.; Mackay, S.; Riddington, G. The Economic Impact of Sports, Sporting Events, and Sports Tourism in the U.K. The DREAM™ Model. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2005, 5, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H. The Economic Impact of Visitors at Major Multi-sport Events. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2005, 5, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzman, J. Economic impact: Sport tourism and the city. J. Sport Tour. 2001, 6, 14–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzman, J. Economic impact: Sport tourism and the city. J. Sport Tour. 2005, 10, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M.J.; Norman, W.C. Estimating the Economic Impacts of Seven Regular Sport Tourism Events. J. Sport Tour. 2003, 8, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, T. The Impact of Sports Events on Inbound Tourism in New Zealand. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakakis, P.; Papadaskalopoulos, A.; Lagos, D. Multipliers and impacts of active sport tourism in the Greek region of Messinia. Tour. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moital, M. The impact of sports events at tourist destination level. Motricidade 2019, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Perić, M. Estimating the Perceived Socio-Economic Impacts of Hosting Large-Scale Sport Tourism Events. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, D.M.; Swart, K.; Bob, U.; Moodley, V. Socio-economic Impacts of Sport Tourism in the Durban Unicity, South Africa. J. Sport Tour. 2003, 8, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoroge, J.M.; Atieno, L.; Nascimento, D.V.D. Sports Tourism and Perceived Socio-Economic Impact In Kenya: The Case Of Machakos County. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 23, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S.; Aitchison, C. The Role of Food Tourism in Sustaining Regional Identity: A Case Study of Cornwall, South West England. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Garcia, R.J.; Ano-Sanz, V.; Parra-Camacho, D.; Calabuig-Moreno, F. Perception of residents about the impact of sports tourism on the community: Analysis and scale-validation. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Concari, A.; Kok, G.; Martens, P. A Systematic Literature Review of Concepts and Factors Related to Pro-Environmental Consumer Behaviour in Relation to Waste Management Through an Interdisciplinary Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781544318486. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. Writing Narrative Literature Reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1997, 1, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Pearce, T.; Ford, J.D. Systematic review approaches for climate change adaptation research. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasojevic, B.; Lohmann, G.; Scott, N. Air transport and tourism—A systematic literature review (2000–2014). Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 21, 975–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.W.; Thok, S.; O’Rourke, V.; Pearce, T. Sustainable tourism and its use as a development strategy in Cambodia: A systematic literature review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 797–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, M.; Ruiz-Chico, J.; Peña-Sánchez, A.R.; López-Sánchez, J.A. A Bibliometric Analysis of Sports Tourism and Sustainability (2002–2019). Sustainability 2020, 12, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersulić, A.; Perić, M.; Wise, N. Assessing and Considering the Wider Impacts of Sport-Tourism Events: A Research Agenda Review of Sustainability and Strategic Planning Elements. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.A.; Assenov, I. The genesis of a new body of sport tourism literature: A systematic review of surf tourism research (1997–2011). J. Sport Tour. 2012, 17, 257–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-F.; Hwang, G.-J. Trends and research issues of mobile learning studies in hospitality, leisure, sport and tourism education: A review of academic publications from 2002 to 2017. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2018, 28, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.; Glinia, E. Empathy and Sport Tourism Services: A Literature Review. J. Sport Tour. 2003, 8, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J. Sport Tourism: A Critical Analysis of Research. Sport Manag. Rev. 1998, 1, 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M. Sports Tourism Research 2000–2004: A Systematic Review of Knowledge and a Meta-Evaluation of Methods. J. Sport Tour. 2006, 11, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M. Progress in sports tourism research? A meta-review and exploration of futures. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rebull, M.-V.; Rudchenko, V.; Martín, J.-C. The Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 24, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, M.; Moraes, M.; Breda, Z.; Guizi, A.; Da Costa, C.M.M. Overtourism and tourismphobia. Tourism 2020, 68, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcês, S.; Pocinho, M.M.F.D.D.; De Jesus, S.N.; Rieber, M.S.; University of Madeira; University of Algarve. Positive psychology and tourism: A systematic literature review. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2018, 14, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, R.; Höckert, E.; Lüthje, M.; Kugapi, O.; Mazzullo, N. Cultural sensitivity in Sámi tourism: A systematic literature review in the Finnish context. Matkailututkimus 2020, 16, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.; Estevão, C.; Fernandes, C.I.; Leitão, J. Film induced tourism: A systematic literature review. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2017, 13, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Yazdani, H.R.; Saghafi, F.; Jalilvand, M.R. Developing strategic relationships for religious tourism businesses: A systematic literature review. EuroMed J. Manag. 2017, 2, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachao, S.; Breda, Z.; Fernandes, C.; Joukes, V. Food tourism and regional development: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Jeong, E. Park Service Quality in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review and Keyword Network Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peachey, J.W.; Schulenkorf, N.; Hill, P. Sport-for-development: A comprehensive analysis of theoretical and conceptual advancements. Sport Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thees, H.; Pechlaner, H.; Olbrich, N.; Schuhbert, A. The Living Lab as a Tool to Promote Residents’ Participation in Destination Governance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International. Qualitative Data Analysis Software|NVivo. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- Le, P.T.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Chileshe, N.; Rameezdeen, R. Taxonomy of risks in PPP transportation projects: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.Z.; Dilshad, M. Higher Education and Gloval Development: A Cross Cultural Qualitative Study in Pakistan. High. Educ. Future 2015, 2, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Jones, A. Qualitative data analysis with NVIVO. J. Educ. Teach. 2014, 40, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, B.C. Using NVivo to analyze qualitative classroom data on constructivist learning environments. Qual. Rep. 2004, 9, 589–603. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, E. Dealing with Data: Using NVivo in the Qualitative Data Analysis Process. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2002, 3, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hinch, T.; Holt, N.L. Sustaining places and participatory sport tourism events. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1084–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.-K.; Yu, J.-G. Sustaining Sporting Destinations through Improving Tourists’ Mental and Physical Health in the Tourism Environment: The Case of Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirehie, M.; Gibson, H. Empirical testing of destination attribute preferences of women snow-sport tourists along a trajectory of participation. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buning, R.J.; Gibson, H.J. The role of travel conditions in cycling tourism: Implications for destination and event management. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Coupling Development Mechanism of Sports Industry and Tourism Industry in Hunan Province. Ekoloji 2019, 28, 3951–3960. [Google Scholar]

- Yfantidou, G.; Spyridopoulou, E.; Kouthouris, C.; Balaska, P.; Matarazzo, M.; Costa, G.; Georgia, Y.; Eleni, S.; Charilaos, K.; Panagiota, B.; et al. The future of sustainable tourism development for the Greek enterprises that provide sport tourism. Tour. Econ. 2016, 23, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogan, E.; Moldoveanu, E.A.; Iamandei, M.I. The Perspective of Sports Tourism Development in Bucharest, Romania. Qual. Access Success 2018, 19, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ziakas, V.; Costa, C.A. The Use of an Event Portfolio in Regional Community and Tourism Development: Creating Synergy between Sport and Cultural Events. J. Sport Tour. 2011, 16, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Jun, H.M.; Walker, M.; Drane, D. Evaluating the perceived social impacts of hosting large-scale sport tourism events: Scale development and validation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S.R.; Lombardi, R. Socio-economic value co-creation and sports tourism: Evidence from Tasmania. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 12, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinot, É.; Trespeuch, L. Sport Events and Green Values: Which Impacts for Tourism Destinations and Stakeholders? J. Tour. Res. Hosp. 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinch, T.; Ito, E. Sustainable Sport Tourism in Japan. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 15, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundet, L.; Coenders, G. Greenways: A sustainable leisure experience concept for both communities and tourists. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, L.E.; Gómez, E. Surf localism in Costa Rica: Exploring territoriality among Costa Rican and foreign resident surfers. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, J.J.; Petrovic, M.D. Sport and Recreation Influence upon Mountain Area and Sustainable Tourism Development. J. Environ. Tour. Anal. 2013, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, K.; Nicholson, M.; Randle, E.; Donaldson, A.; O’Halloran, P.; Staley, K.; Kappelides, P.; Nelson, R.; Belski, R. Participant-Centered sport development: A case study using the leisure constraints of women in regional communities. Leis. Sci. 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, K.; Chen, N.; King, C.; Funk, D.C. Sport Tourists’ Involvement with a Destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2011, 37, 100–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakas, V. Leveraging Sport Events for Tourism Development: The Event Portfolio Perspective. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2020, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, S.; Alfs, C.; Beech, J.; Kaspar, R. Challenges of tourism development in winter sports destinations and for post-event tourism marketing: The cases of the Ramsau Nordic Ski World Championships 1999 and the St Anton Alpine Ski World Championships. J. Sport Tour. 2013, 18, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.-K.; Yu, J.-G. Determinants of Behavioral Intentions in the Context of Sport Tourism with the Aim of Sustaining Sporting Destinations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubizolles, S. Sport and social cohesion in a provincial town in South Africa: The case of a tourism project for aid and social development through football. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2013, 50, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homafar, F.; Honari, H.; Heidary, A.; Heidary, T.; Emami, A. The role of sport tourism in employment, income and economic development. J. Hosp. Manag. Tour. 2011, 2, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotnian, S.; Najafizadeh, M.; Roughani, M. Factors of sustainable development of sports Tourism: Identifying barriers and outlines. Int. Res. J. Appl. Basic Sci. 2013, 4, 2598–2601. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.-W.; Lu, H.-F. Valuing Residents’ Perceptions of Sport Tourism Development in Taiwan’s North Coast and Guanyinshan National Scenic Area. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 398–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.L.; Butler, J.R.; Sheaves, M.; Wani, J. Sport fisheries: Opportunities and challenges for diversifying coastal livelihoods in the Pacific. Mar. Policy 2013, 42, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pookaiyaudom, G. The Development of the Thai Long-boat Race as a Sports Tourism and Cultural Product. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 16, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, K. Event start-ups as catalysts for place, sport and tourism development: Moment scapes and geographical considerations. Sport Soc. 2020, 23, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choe, Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.J. For Sustainable Benefits and Legacies of Mega-Events: A Case Study of the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics from the Perspective of the Volunteer Co-Creators. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobay, G. Effects of Sport Tourism on Temperate Grassland Communities (Duna-Ipoly National Park, Hungary). Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2017, 15, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Long, Y. Development and research on rural regional characteristic sports tourism industry: A case study of Southern Jiangxi Province. Asian Agric. Res. 2014, 6, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, E.; Agrusa, J.F.; Richins, H. Tourist Destination Governance: Practice, Theory and Issues; CAB International: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 9781845938314. [Google Scholar]

- Dissart, J.-C.; Dehez, J.; Marsat, J.-B. (Eds.) Tourism, Recreation and Regional Development: Perspectives from France and Abroad; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781138083844. [Google Scholar]

- Dredge, D.; Gyimóthy, S. Collaborative Economy and Tourism. Perspectives, Politics, Policies and Prospects; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 9783319517995. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, B.J.R.; Crouch, G.I. Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective, 2nd ed.; CABI Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, A. Fast Friends: A Running Camp in Kenya. The Guardian. 16 April 2011. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2011/apr/16/iten-kenya-running-athletics-training-camp (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Finn, A. Five of the Best Running Holidays. Financial Times. 19 July 2019. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/c1314c7a-a6d2-11e9-90e9-fc4b9d9528b4 (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Pechlaner, H.; Herntrei, M.; Kofink, L. Growth strategies in mature destinations: Linking spatial planning with product development. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2009, 57, 285–307. [Google Scholar]

- Băndoi, A.; Jianu, E.; Enescu, M.; Axinte, G.; Sorin, T.; Firoiu, D. The Relationship between Development of Tourism, Quality of Life and Sustainable Performance in EU Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beritelli, P.; Buffa, F.; Martini, U. The coordinating DMO or coordinators in the DMO?—An alternative perspective with the help of network analysis. Tour. Rev. 2015, 70, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenfeld, A. Tourism Diversification and Its Implications for Smart Specialisation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyras, A.; Peachey, J.W. Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Form | Characteristics | Problems/Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Responsible tourism | Close relationship to the environment, economy, culture, and society Economic benefits for locals Enhances well-being | Establishing control and management frameworks for external corporations in terms of social justice |

| Ecotourism | Conserving the environment, sustaining the well-being of locals | Upgrading the local contribution and benefits in opposition to external operators and market players |

| Fair trade tourism | Building sustainable supply chains and distributing benefits fairly | Actors from developed countries may leverage control over developing ones Control of licensing remains external |

| Pro-poor-tourism | Increasing benefits for the poor Contributing to poverty reduction by unlocking opportunities | Partially used as an instrument for capitalist penetration due to international cooperation |

| Community-based tourism | Local ownership/management of tourism products | Possible lack of local skills/capabilities and risk of conflicts due to missing coordination system |

| Database | Science-Direct | CAB International | Taylor and Francis Online | Web of Science | ECONLit | SURF | MDPI | SAGE Journals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tourism AND Community AND Sport | 8.862 | 1.443 | 28.410 | 269 | 1.940 | 45 | 638 | 7.738 |

| Tourism AND Development AND Sport | 11.662 | 2.839 | 38.190 | 551 | 7.824 | 347 | 843 | 10.343 |

| Destination AND Sport AND Tourism | 5.708 | 1.601 | 14.834 | 404 | 3.201 | 76 | 399 | 4026 |

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity of publications | 3 | 4 | - | 6 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 6 |

| Theories & Concepts | |

|---|---|

| Aim of the study | Methods |

| Statements | Key Issues |

|---|---|

| Challenges and Risks “[…] the perceived benefits and drawbacks of sport tourism are not experienced evenly across small business owners.” [29] (p. 13) “Sports tourism makes sports more expensive for residents.” [129] (p. 151) “Sport tourism has resulted in traffic congestion, noise and pollution. […] Construction of sport tourist facilities has destroyed the natural environment.” [25] (p. 127) “Majority of local residents may find their participation in event planning irrelevant in influencing sports events tourism development.” [63] (p. 11) |

|

| Opportunities and Benefits “Sports tourism helps keep culture alive and helps maintain the ethnic identity of local residents.” [129] (p. 152) “Community support […] leads to the success of tourism in the destination.” [25] (p. 134) “Sport and tourism can play a major role in the bringing together of communities” [24] (p. 58) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herbold, V.; Thees, H.; Philipp, J. The Host Community and Its Role in Sports Tourism—Exploring an Emerging Research Field. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410488

Herbold V, Thees H, Philipp J. The Host Community and Its Role in Sports Tourism—Exploring an Emerging Research Field. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410488

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerbold, Valentin, Hannes Thees, and Julian Philipp. 2020. "The Host Community and Its Role in Sports Tourism—Exploring an Emerging Research Field" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410488

APA StyleHerbold, V., Thees, H., & Philipp, J. (2020). The Host Community and Its Role in Sports Tourism—Exploring an Emerging Research Field. Sustainability, 12(24), 10488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410488