Adventure Tourism in the Spanish Population: Sociodemographic Analysis to Improve Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Methods

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Total | Men | Women | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Only Spanish | 369 (97.1) | 220 (96.9) | 149 (97.4) | 0.94 |

| Only Foreign | 5 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Spanish and Foreign | 6 (1.6) | 4 (1.8) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Marital status | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Single | 193 (50.8) | 117 (51.5) | 76 (49.7) | 0.49 |

| Married | 150(39.5) | 85 (37.4) | 65 (42.5) | |

| Widowed | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Separate | 5 (1.3) | 4 (1.8) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Divorced | 29 (7.6) | 20 (8.8) | 9 (5.9) | |

| Cohabitation with a Partner | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Cohabitation with their spouse | 146 (38.4) | 85 (37.4) | 61 (39.9) | 0.61 |

| Cohabitation with a common-law partner | 42 (11.1) | 23 (10.1) | 19 (12.4) | |

| Not cohabitation together as a couple | 192 (50.5) | 119 (52.4) | 73 (47.7) | |

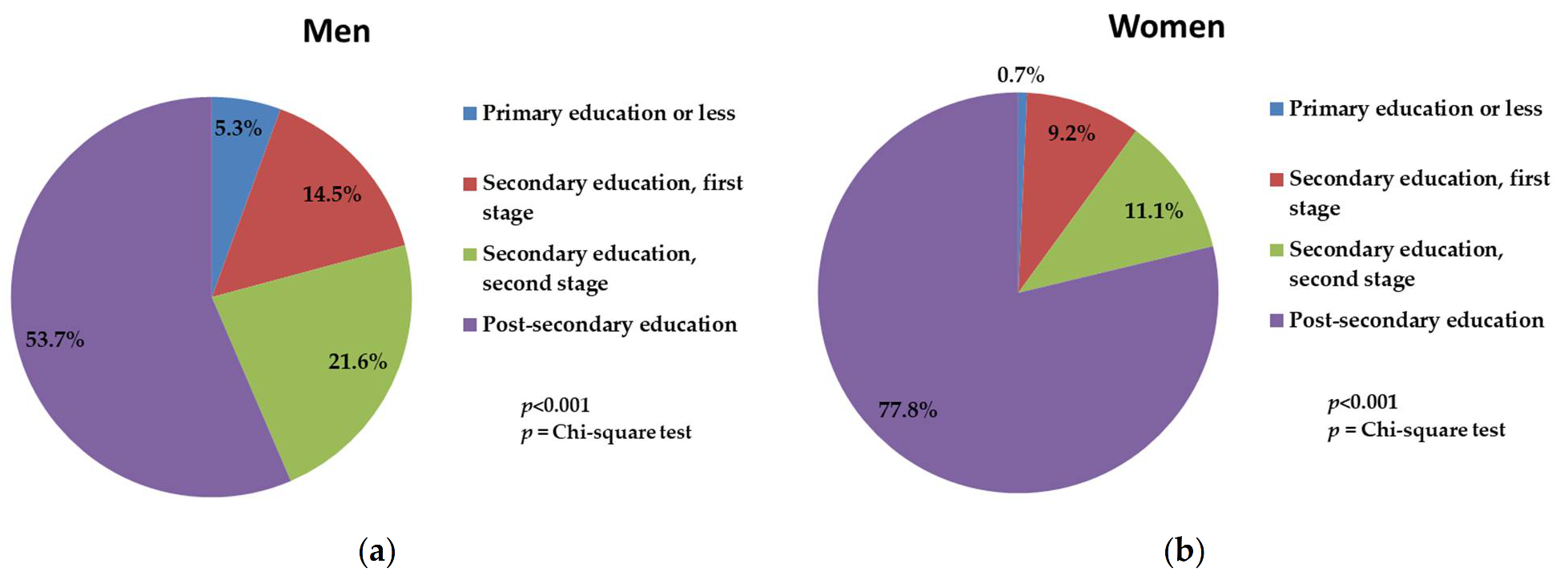

| Level of studies | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Primary education or less | 13 (3.4) | 12 (5.3) | 1 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Secondary education, first stage | 47 (12.4) | 33 (14.5) | 14 (9.2) | |

| Secondary education, second stage | 66 (17.4) | 49 (21.6) | 17 (11.1) | |

| Post-secondary education | 241 (63.4) | 122 (53.7) | 119 (77.8) | |

| Missing values | 13 (3.4) | 11 (4.8) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Relationship between economic activity | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Employed | 294 (77.4) | 172 (75.8) | 122 (79.7) | 0.57 |

| Unemployed | 18 (4.7) | 9 (4.0) | 9 (5.9) | |

| Retired | 9 (2.4) | 7 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Other inactive | 46 (12.1) | 28 (12.3) | 18 (11.8) | |

| Missing values | 13 (3.4) | 11 (4.8) | 2 (1.3) | |

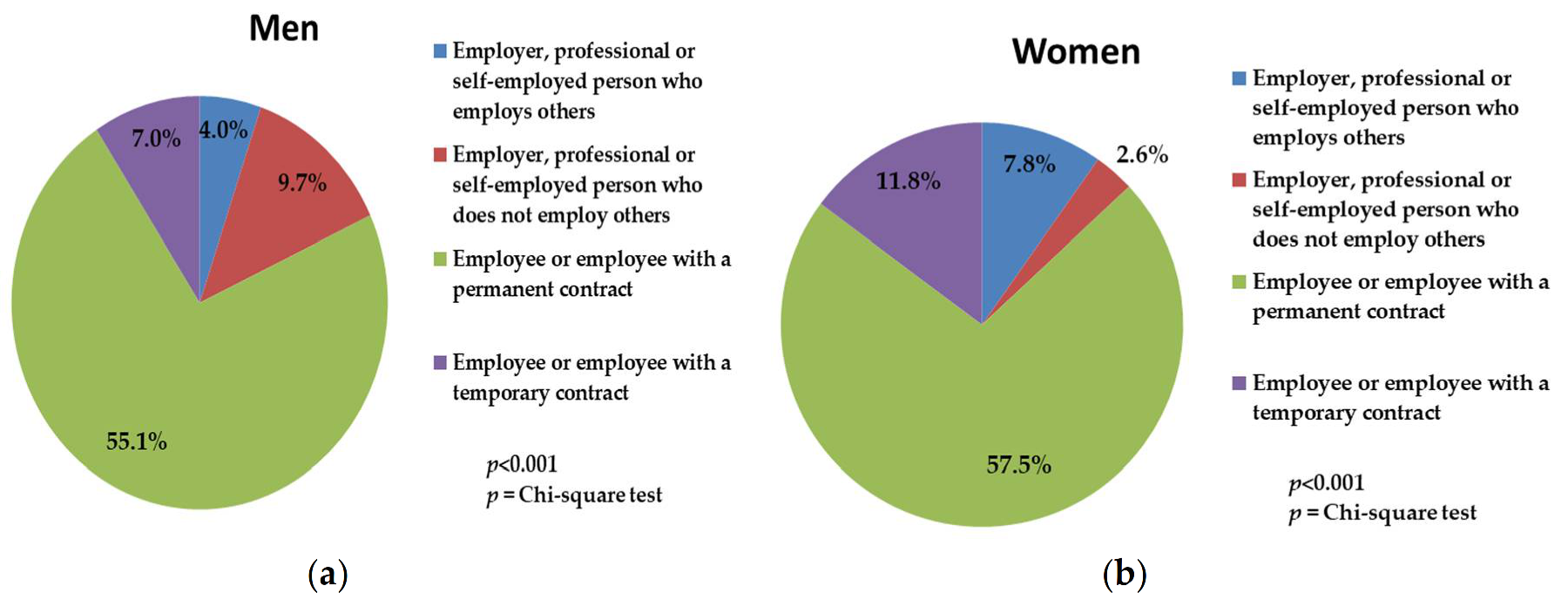

| Professional status in the job performed | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Employer, professional or self-employed person who employs others | 21 (5.5) | 9 (4.0) | 12 (7.8) | 0.01 |

| Employer, professional or self-employed person who does not employ others | 26 (6.8) | 22 (9.7) | 4 (2.6) | |

| Employee or employee with a permanent contract | 213 (56.1) | 125 (55.1) | 88 (57.5) | |

| Employee or employee with a temporary contract | 34 (8.9) | 16 (7.0) | 18 (11.8) | |

| Missing values | 86 (22.6) | 55 (24.2) | 31 (20.3) | |

| Type of household | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Single household | 51 (13.4) | 36 (15.9) | 15 (9.8) | 0.24 |

| Single parent cohabitation with a child | 45 (11.8) | 22 (9.7) | 23 (15.0) | |

| Couple without children cohabitation at home | 60 (15.8) | 38 (16.7) | 22 (14.4) | |

| Couple with children cohabitation at home | 207 (54.5) | 122 (53.7) | 85 (55.6) | |

| Other household | 17 (4.5) | 9 (4.0) | 8 (5.2) | |

| Location of secondary housing | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Spain | 95 (25.0) | 56 (24.7) | 39 (25.5) | 0.85 |

| Foreign country | 285 (75.0) | 171 (75.3) | 114 (74.5) | |

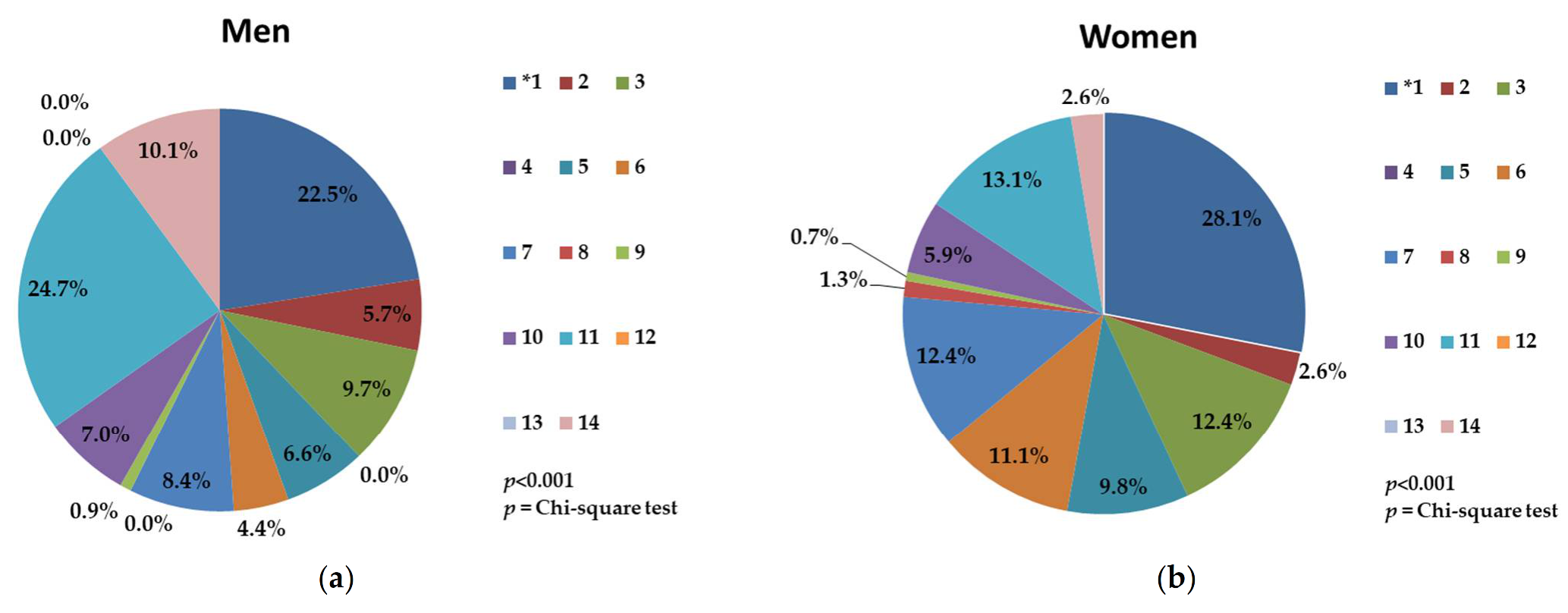

| Type of Accommodation | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Hotel or apartment hotel | 94 (24.7) | 51 (22.5) | 43 (28.1) | <0.001 |

| Hostel | 17 (4.5) | 13 (5.7) | 4 (2.6) | |

| Complete housing for rent | 41 (10.8) | 22 (9.7) | 19 (12.4) | |

| Room for rent in a private home | - | - | - | |

| Rural tourism accommodation | 30 (7.9) | 15 (6.6) | 15 (9.8) | |

| Shelter | 27 (7.1) | 10 (4.4) | 17 (11.1) | |

| Camps | 38 (10.0) | 19 (8.4) | 19 (12.4) | |

| Cruise | 2 (0.5) | - | 2 (1.3) | |

| Other market accommodations | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Home ownership | 25 (6.6) | 16 (7.0) | 9 (5.9) | |

| Family, friend or company housing | 76 (20.0) | 56 (24.7) | 20 (13.1) | |

| Shared use housing | - | - | - | |

| Swapped homes | - | - | - | |

| Other non-market accommodations | 27 (7.1) | 23 (10.1) | 4 (2.6) | |

| Main means of transport | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Air transport | 60 (15.8) | 34 (15.0) | 26 (17.0) | |

| Cruise | - | - | - | |

| Ferry | 3 (0.8) | - | 3 (2.0) | |

| Own, leased or rented boat | - | - | - | 0.30 |

| Car or other private cars owned or leased | 276 (72.6) | 169 (74.4) | 107 (69.9) | |

| Car or other private cars rented without a driver from rental companies | 5 (1.3) | 4 (1.8) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Taxis or carpooling with payment to the driver | - | - | - | |

| Car or carpooling with payment to the driver | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | - | |

| Bus | 27 (7.1) | 14 (6.2) | 13 (8.5) | |

| Train | 8 (2.1) | 5 (2.2) | 3 (2.0) | |

| Non-motorized land transport | - | - | - |

| Variable | Air transport | Private cars | Bus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Only Spanish | 55 (14.5) | 276 (72.7) | 27 (7.1) |

| Only Foreign | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| Spanish and Foreign | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Marital status | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Single | 31 (8.2) | 130 (34.3) | 24 (6.3) |

| Married | 21 (5.5) | 124 (32.7) | 3 (0.8) |

| Widowed | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Separate | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Divorced | 5 (1.3) | 24 (6.3) | 0 (0) |

| Cohabitation with a Partner | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Cohabitation with their spouse | 19 (5.0) | 123 (32.4) | 3 (0.8) |

| Cohabitation with a common-law partner | 10 (2.6) | 30 (7.9) | 0 (0) |

| Not cohabitation together as a couple | 31 (8.2) | 129 (34.0) | 24 (6.3) |

| Level of studies | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Primary education or less | 0 (0) | 12 (3.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Secondary education, first stage | 3 (0.8) | 33 (9.0) | 11 (3.0) |

| Secondary education, second stage | 8 (2.2) | 51 (13.9) | 2 (0.5) |

| Post-secondary education | 49 (13.4) | 177 (48.2) | 9 (2.5) |

| Relationship between economic activity | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Employed | 50 (13.6) | 226 (61.6) | 8 (2.2) |

| Unemployed | 2 (0.5) | 15 (4.1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Retired | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Other inactive | 5 (1.4) | 27 (7.4) | 14 (3.8) |

| Professional status in the job performed | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Employer, professional or self-employed person who employs others | 3 (1.0) | 15 (5.1) | 0 (0) |

| Employer, professional or self-employed person who does not employ others | 9 (3.1) | 17 (5.7) | 0 (0) |

| Employee or employee with a permanent contract | 33 (11.2) | 172 (58.5) | 2 (0.7) |

| Employee or employee with a temporary contract | 5 (1.7) | 22 (7.5) | 6 (2.0) |

| Type of household | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Single household | 8 (2.1) | 39 (10.3) | 3 (0.8) |

| Single parent cohabitation with a child | 13 (3.4) | 26 (6.9) | 5 (1.3) |

| Couple without children cohabitation at home | 11 (2.9) | 46 (12.1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Couple with children cohabitation at home | 25 (6.6) | 159 (41.8) | 17 (4.5) |

| Other household | 3 (0.8) | 12 (3.2) | 1 (0.3) |

| Location of secondary housing | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Spain | 10 (2.6) | 78 (20.5) | 6 (1.6) |

| Foreign country | 50 (13.2) | 204 (53.7) | 21 (5.5) |

| Type of Accommodation | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Hotel or apartment hotel | 24 (6.3) | 62 (16.3) | 6 (1.6) |

| Hostel | 5 (1.3) | 10 (2.6) | 2 (0.5) |

| Complete housing for rent | 10 (2.6) | 30 (7.9) | 0 (0) |

| Room for rent in a private home | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Rural tourism accommodation | 3 (0.8) | 26 (6.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| Shelter | 3 (0.8) | 12 (3.2) | 11 (2.9) |

| Camps | 3 (0.8) | 31 (8.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Cruise | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) |

| Other market accommodations | 0 (0) | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

| Home ownership | 0 (0) | 25 (6.6) | 0 (0) |

| Family, friend or company housing | 8 (2.1) | 59 (15.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Shared use housing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Swapped homes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other non-market accommodations | 2 (0.5) | 24 (6.4) | 1 (0.3) |

References

- Rojo, I.M. Dirección y Gestión de Empresas del Sector Turístico; Ediciones Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agüera, F.O. El turismo comunitario como herramienta para el desarrollo sostenible de destinos subdesarrollados. Nómadas. Crit. J. Soc. Jurid. Sci. 2013, 38, 42908. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, J.F. El turismo sostenible en España: Análisis de los planes estratégicos de sostenibilidad de Zaragoza y Barcelona. ROTUR Rev. Ocio Tur. 2020, 14, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumara, K. The Sociological Sphere of Tourism as A Social Phenomenon. 2011. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2262641/The_Sociological_Sphere_of_Tourism_as_a_Social_Phenomenon (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Glaesser, D. Crisis Management in the Tourism Industry; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.C.M. Análisis de la calidad del servicio hotelero mediante la Escala de SERVQUAL Caso: Hoteles de Turismo del Municipio Libertador del Estado Mérida. Visión Gerenc. 2007, 6, 269–297. [Google Scholar]

- Dziubinski, Z.; Jasny, M. Free time, tourism and recreation: Some sociological reflections. Ido Mov. Cult. J. Martial Arts Anthropol. 2017, 17, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Włoch, R. Two dynamics of globalization in the context of a sports mega-event: The case of Uefa Euro 2012 in Poland. Globalizations 2020, 17, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.; Hall, D. Rural Tourism and Recreation: Principles to Practice; Cabi: Wallingford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, H.; Morrison, A.; O’Leary, J. Turismo de Aventura. 1996. Available online: http://www.turismoaventura.com/comunidad/contenidos/defTA/index.html (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Daly, J.; Goodland, R.; Serafy, S.; Droste, B. Medio ambiente y desarrollo sostenible. Brundtland 1997, 33, 1–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho, A.; Buhalis, D. Introducción al turismo. Madr. Organ. Mund. Tur. 1998, 392. [Google Scholar]

- Cañaveral, I.P.; Prados, J.L.P. Ecoturismo, sostenibilidad y comunidad local. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pedro_Ernesto_Moreira_Gregori/publication/324124228_TURISMO_Y_SOCIEDAD_EN_ANDALUCIA/links/5abf64e3aca27222c7583136/TURISMO-Y-SOCIEDAD-EN-ANDALUCIA.pdf#page=306 (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Delgado, J. Turismo Responsable: Una visión homeostática. 2004. Available online: https://www.ecoportal.net/temas-especiales/desarrollo-sustentable/turismo_responsable_una_vision_homeostatica/ (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Blasco, M.C. Turismo, identidad y reivindicación sociocultural en Chile. Tur. sostenibilidad: V Jorn. Investig. Tur. 2012, 2012, 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Association, A.T.T. Adventure Tourism Market Study 2013; Adventure Travel Trade Association and the George Washington University: Monroe, WA, USA, 2013; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rantala, O.; Rokenes, A.; Valkonen, J. Is adventure tourism a coherent concept? A review of research approaches on adventure tourism. Ann. Leis. Res. 2018, 21, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Edwards, D.; Darcy, S.; Redfern, K. A tri-method approach to a review of adventure tourism literature: Bibliometric analysis, content analysis, and a quantitative systematic literature review. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 997–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, M.; Gross, S. Tourism research on adventure tourism—Current themes and developments. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 28, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötter, M.J.; Geldenhuys, S.; Potgieter, M. Demographic profile of adventure tourists in Pretoria. Glob. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 6, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, Z.; Afandi, S.H.M.; Ramachandran, S.; Shuib, A.; Kunasekaran, P. Adventure Tourism in Kampar, Malaysia: Profile and Visit Characteristics of Domestic Visitors. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 19, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Giddy, J.K. A profile of commercial adventure tourism participants in South Africa. Anatolia 2018, 29, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Miravet, D. The determinants of tourist use of public transport at the destination. Sustainability 2016, 8, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sostenible, D. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Turístico, E. ¿Qué es el Turismo de Aventura? Hablemos de Turismo: Guadalajara, Mexica, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, C.G. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS): Una revisión crítica. Pap. Relac. Ecosociales Cambio Glob. 2018, 140, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, M.E.G.; Juan, F.R. Actas del IV Congreso Internacional de Educación Física e Interculturalidad. El Deporte Unión de Culturas [CD ROM]. In El Ocio y la Recreación Físicodeportiva en la Sociedad Española Actual; Universidad de Murcia: Cancún, Mexican, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé, L. Environmental education: Possibilities and constraints. Educ. Pesqui. 2005, 31, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollo, J.F.V.; Gómez, M.J.M. Efectos del turismo en las estructuras regionales periféricas: Una aproximación analítica. Millars Espai Hist. 1998, 21, 109–144. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Adventure tourism research: A guide to the literature. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2006, 31, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.J.M. ¿Las mujeres no hacen deporte porque no quieren? ¿ Los hombres practican el deporte que quieren? El género como variable de análisis de la práctica deportiva de las mujeres y de los hombres; Universidade da Coruña: Coruña, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, J. Sporting Females: Critical Issues in the History and Sociology of Women’s Sport; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Naida, N.; Shaw, C.; Cook, S.D. The Adventure Travel Report, 1997; Travel Industry Association of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Seminario, M.M. Perfil del Turista de Aventura. 2008. Available online: www.promperu.gob.pe/turismoIN (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Acebes, A.S.M.; Fernández, F.R. Estudio comparativo de empresas de turismo de aventura de la provincia de Valencia. Gran Tour Rev. Investig. Turísticas 2011, 3, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadra, S.M.; Morales, P.C.; Agüera, F.O. El turismo de aventura: Concepto, evolución, características y mercado meta. El caso de Andalucía. Tur. Innovación VI Jorn. Investig. Tur. 2013, 2013, 327–343. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, J.R.; Carmona, R.M.; Arroyo, C.G.; Redondo, F.M.; Gordillo, M.Á.G.; Adsuar, J.C. Trekking tourism in spain: Analysis of the sociodemographic profile of trekking tourists for the design of sustainable tourism services. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barcelona, A. Barcelona Tourism for 2020: A Collective Strategy for Sustainable Tourism; Tourism Department Manager’s Office for Enterprise and Tourism: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.L. Parques Nacionales en España. Comparación y Atractivos Turísticos; Universidad de Jaén: Jaén, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Talaya, Á.E.; Romero, C.L.; Martínez, M.E.A.; del Amo, M.d.C.A. ¿ Conocemos a los visitantes de Castilla-La Mancha? Un análisis comparativo turistas vs. excursionistas. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2011, 9, 531–542. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, N.A.; Kiatkawsin, K. Examining Vietnamese Hard-Adventure Tourists’ Visit Intention Using an Extended Model of Goal-Directed Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minotta, D.G. El turismo joven: Conceptualización y alcances. Rev. Intersección Even. Tur. Gastron. Moda 2014, 2, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, W.C.; Franco, M.C.; Franco, O.C.; Lino, X.R. Preferencias para el turismo de aventura en la elaboración de un paquete turístico: Caso Santa Elena, Ecuador. Rev. Interam. Ambiente Tur. 2018, 14, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogollón, J.M.H.; Cerro, A.M.C.; di Clemente, E. El turista rural en entornos de alta calidad medioambiental. Rev. Análisis Turístico 2013, 16, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Leco, F.; Pérez, A.; Hernández, J.; Campón, A. Rural tourists and their attitudes and motivations towards the practice of environmental activities such as agrotourism. IJER 2013, 17, 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Henche, B.G. Características diferenciales del producto turismo rural. Cuad. Tur. 2005, 15, 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Giddy, J.K.; Webb, N.L. The influence of the environment on adventure tourism: From motivations to experiences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 2124–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, E.E.; Milla, M.C.; Tiznado, J.L. Turismo de aventura, su impacto ambiental y propuesta de mitigación en la quebrada de Quillcayhuanca. Rev. Investig. Univ. Le Cordon Bleu 2017, 4, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco, O. Los impactos del turismo en el Perú. Ind. Data 2003, 6, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, R.; Benayas, J. Los Estudios de Capacidad de Acogida y su Contribución Para Establecer Modelos de Turismo Sostenible en Espacios Naturales; Departamento de Ecología. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tello, S. Patrimonio: Turismo y comunidad. Rev. Tur. Patrim. 2000, 1, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, J.L. Determinantes de la Motivación Cultural en la Elección de Destinatarios; El Caso Español: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno, D.E. Plan de Acción para la Implementación de la Agenda 2030. Hacia una Estrategia Española de Desarrollo Sostenible. 2018. Available online: http://www.exteriores.gob.es/Portal/es/SalaDePrensa/Multimedia/Publicaciones/Documents/PLAN%20DE%20ACCION%20PARA%20LA%20IMPLEMENTACION%20DE%20LA%20AGENDA (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Márquez, L.A.M.; Colmenares, S.P. Revisión sobre capacidad de carga turística y la prevención de problemas ambientales en destinos emergentes. Anu. Tur. Soc. 2019, 24, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, V.P. Carrying capacity analysis and destination development: A case study of Gangotri tourists/pilgrims’ circuit in the Himalaya. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, A.B.; Leco, F.; Pérez, A. Visitors’ Perception of the Overcrowding of a Protected Natural Area: A Case Applied to the Natural Reserve “Garganta de los Infiernos”(Caceres, Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

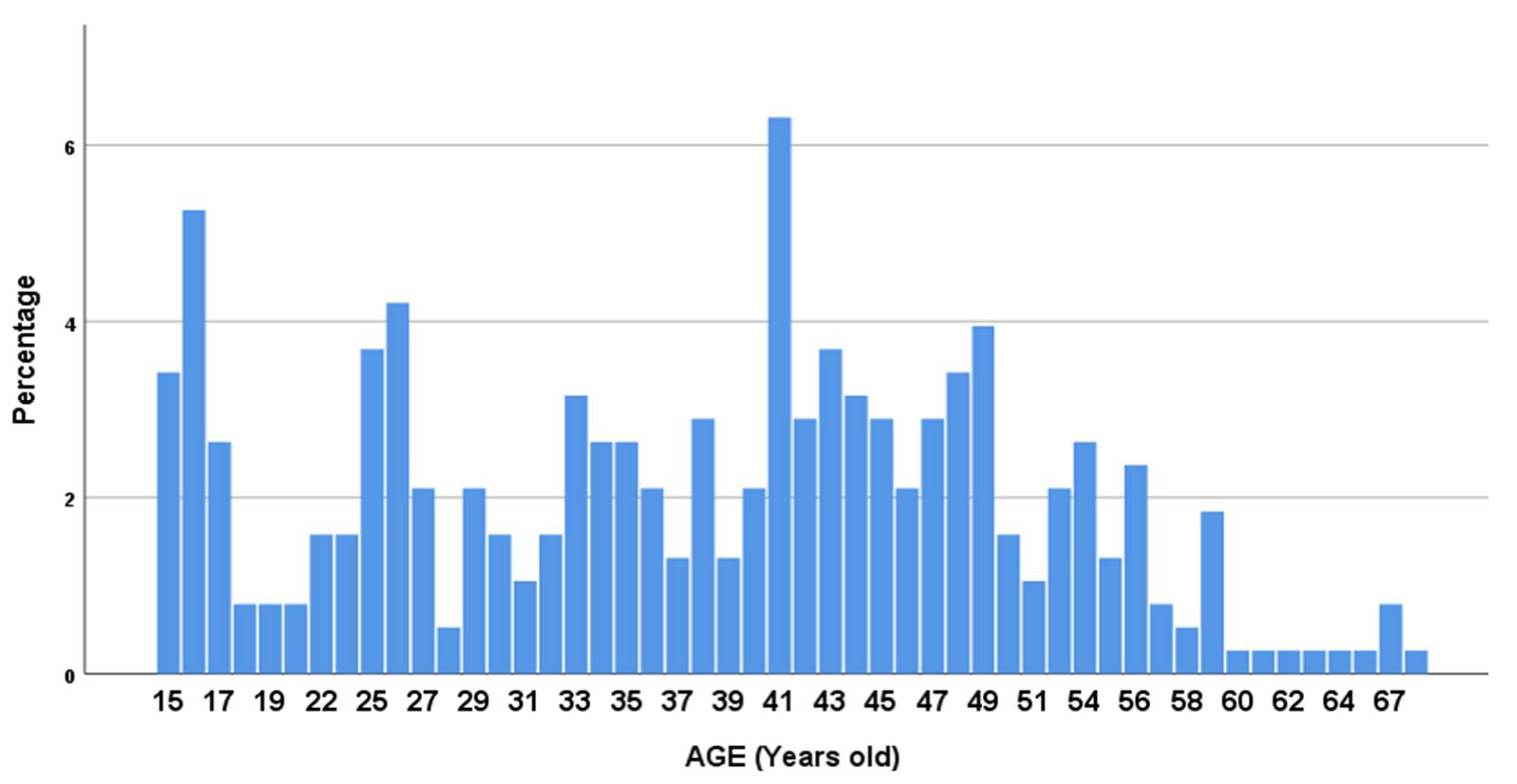

| Age (Years) | Total | Men | Women | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | 40.00 (20.00) | 39.00 (20.00) | 40.00 (20.00) | 0.882 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojo-Ramos, J.; Vidal-Espinoza, R.; Palacios-Cartagena, R.P.; Galán-Arroyo, C.; Manzano-Redondo, F.; Gómez-Campos, R.; Adsuar, J.C. Adventure Tourism in the Spanish Population: Sociodemographic Analysis to Improve Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041706

Rojo-Ramos J, Vidal-Espinoza R, Palacios-Cartagena RP, Galán-Arroyo C, Manzano-Redondo F, Gómez-Campos R, Adsuar JC. Adventure Tourism in the Spanish Population: Sociodemographic Analysis to Improve Sustainability. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041706

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojo-Ramos, Jorge, Rubén Vidal-Espinoza, Roxana Paola Palacios-Cartagena, Carmen Galán-Arroyo, Fernando Manzano-Redondo, Rossana Gómez-Campos, and José Carmelo Adsuar. 2021. "Adventure Tourism in the Spanish Population: Sociodemographic Analysis to Improve Sustainability" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041706

APA StyleRojo-Ramos, J., Vidal-Espinoza, R., Palacios-Cartagena, R. P., Galán-Arroyo, C., Manzano-Redondo, F., Gómez-Campos, R., & Adsuar, J. C. (2021). Adventure Tourism in the Spanish Population: Sociodemographic Analysis to Improve Sustainability. Sustainability, 13(4), 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041706